Abstract

Objectives

Respiratory diseases are ranked second in Europe in terms of mortality, prevalence and costs. Studies have shown that extreme heat has a large impact on mortality and morbidity, with a large relative increase for respiratory diseases. Expected increases in mean temperature and the number of extreme heat events over the coming decades due to climate change raise questions about the possible health impacts. We assess the number of heat-related respiratory hospital admissions in a future with a different climate.

Design

A Europe-wide health impact assessment.

Setting

An assessment for each of the EU27 countries.

Methods

Heat-related hospital admissions under a changing climate are projected using multicity epidemiological exposure–response relationships applied to gridded population data and country-specific baseline respiratory hospital admission rates. Times-series of temperatures are simulated with a regional climate model based on four global climate models, under two greenhouse gas emission scenarios.

Results

Between a reference period (1981–2010) and a future period (2021–2050), the total number of respiratory hospital admissions attributed to heat is projected to be larger in southern Europe, with three times more heat attributed respiratory hospital admissions in the future period. The smallest change was estimated in Eastern Europe with about a twofold increase. For all of Europe, the number of heat-related respiratory hospital admissions is projected to be 26 000 annually in the future period compared with 11 000 in the reference period.

Conclusions

The results suggest that the projected effects of climate change on temperature and the number of extreme heat events could substantially influence respiratory morbidity across Europe.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

To assess how heat-related respiratory hospital admissions in Europe could change with increasing temperatures in the near future. Within a range of climate change projections, explore different impact estimates.

Key messages

The 30-year mean annual increase in heat-related respiratory hospital admissions between the periods 1981–2010 and 2021–2050 can be counted in the 10s of thousands because of projected temperature increases. The increase will be different in different parts of Europe with the largest relative increase in southern Europe.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study takes the spatial variation in climate and population density into account in impact calculations, making the estimates valid for countries with large national differences in these factors.

The study results exemplify some of the variation of health impacts under different climate change scenarios, as well as the variations within one scenario, with different underlying climate models.

The use of spatial population data limited the study to exploring the change in all age respiratory hospital for studying heat-related illness; combined with the future increase in the proportion of elderly people, this suggests that the estimated impacts are likely to be conservative.

Introduction

Respiratory diseases are ranked second in Europe in terms of mortality, prevalence and costs.1 This burden is expected to increase, partly due to a changing climate.2 An environmental factor with a large impact on mortality and morbidity in Europe is extreme heat, with large effects on respiratory diseases.3–5 The physiological effects of exposure to heat can be directly heat-related (heat stroke, heat fatigue and dehydration) or can contribute to a worsening of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, electrolyte disorders and kidney problems.4–7 The reasons for an increase in respiratory admissions may be several. The elderly with respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are less fit and suffer often from circulatory problems. Heat influenced admissions due to chronic airway obstruction and asthma increased more than admissions due to chronic bronchitis in a study from New York City,8 but the daily number of admissions seldom allow a study of specific diagnoses. In a recent expert elicitation among European researchers engaged in environmental medicine or respiratory health, extreme heat stood out as the most important climate-related pathway to adverse impacts on respiratory health, more important than changes in air pollutants and allergens.9 A review found that heatwaves have a stronger relative impact on mortality than on emergency room visits and hospital admissions, suggesting that many individuals die before they can get to the hospital.10 However, several studies confirm that heat also affects healthcare utilisation.3 11 During the heatwave of 2003 in France, the Assistance Public Hôpitaux de Paris recorded 2400 additional visits to the emergency care units and 1900 additional hospital admissions.12 During the heatwave in California in 2006, there were almost 1200 excess hospital admissions together with more than 16 000 excess visits to the emergency departments.6

It is possible that hospital admissions could increase in the future owing to temperature changes projected with climate change, assuming no additional acclimatisation. Projected changes include an increase in the global mean temperature of 1.8 to 4°C by the end of this century, with larger increases over land areas at high latitudes, changing seasonal temperatures and increases in the frequency, intensity, duration and spatial extent of heatwaves.13 Recent projections for 2070–2100 suggest that maximum temperatures experienced once every 20 years during the period 1961–1990 could be expected as often as every year in southern Europe and every third and fifth year in northern Europe.14 This means that Europe should expect an increase in both mean temperatures and the number of extreme heat events. Recent heatwaves are consistent with projections. For example, the heatwave that occurred in Europe 2003 could be expected to return every 46 000 years, based on the temperature distribution for the years 1864–2000.15 However, such extreme hot conditions may become much more common at the end of this century due to anthropogenic climate change.16 The uncertainty in this estimated return time is quite high, with a lower bound of the 90% CI of 9000 years. Even so, another heatwave occurred in 2006 with the most anomalous July temperature ever measured in Europe.17 In 2010, Eastern Europe experienced a heatwave with summer temperatures higher than in the last 140 years, resulting in roughly 55 000 excess deaths in Russia.18

The possible impacts of these changes on morbidity, particularly respiratory health, are relatively unexplored.

Aim

The aim of this study is to assess the extent to which changes in the frequency of hot days due to climate change over the next 40 years could affect heat-related respiratory hospital admissions (RHAs) in Europe. Using a range of climate projections, we estimate the change in hospital admissions between a reference period and a future period.

Methods

Climate change and temperature modelling

The Rossby Centre regional atmospheric climate model RCA319 was developed by SMHI (the Swedish meteorological and hydrological institute) to dynamically downscale results from the global climate models CCSM3,20 ECHAM5,21 HadleyCM322 and ECHAM423 to a higher resolution over Europe. RCA3 is run on a horizontal grid spacing of 0.44° (corresponding to approximately 50 km) and a time step of 30 min. Projections are based on the global greenhouse gas emission scenarios A1B and A2 (scenarios are described in detail in the SRES24). Both have been used in climate change health impact assessments (HIA).25–28 A1B is a ‘middle of the road’ scenario and A2 is considered a high-emission scenario, although recent greenhouse gas emissions have been higher. Data from one climate model, under one climate change scenario, are referred to as one climate change projection.

We use aggregated daily projections of maximum temperature and relative humidity data to estimate exposure for the periods 1981–2020 (reference period) and 2021–2050 (future period).

Population and morbidity rates

The annual country-specific rate of RHAs (ICD (International classification of diseases)-9 : 460–519) between 2005 and 2010 were extracted from the WHO's European Health for All Database (http://data.euro.who.int/hfadb) for the EU27 countries. In the dataset, national hospital admissions data are provided by the national public health institutes, health ministries or corresponding functions. The ICD-9 codes were preferred because the epidemiological studies in the PHEWE (Assessment and Prevention of Acute Health Effects of Weather Conditions in Europe) study were based on ICD-9 RHAs. The mean value over the 6 years was used as a baseline morbidity rate. In order to have a fine spatial resolution, official population data were from the History Database of the Global Environment (HYDE) theme within the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.29 These data are gridded on a 0.0833° resolution (approximately 9.45 km) and matched with the climatic data by summing the population within each climatic grid cell.

Exposure–response assumption

The impact calculations were based on the relationship between heat and RHAs (ICD-9 : 460–519) estimated within the European PHEWE project.3 This relationship was based on the analyses of 12 European cities over the 1990s, using the daily maximum apparent temperature (AT), where AT is a combination of the measured temperature and the dew point temperature:

|

where T is the air temperature and DT the dew point temperature, which can be derived from temperature and relative humidity.30 AT accounts for heat stress related not only to the absolute temperature but also to the saturation of the surrounding air, which makes it harder to regulate body temperature by sweating, the most important mechanism to maintain a healthy body temperature.31 32 The PHEWE model also included potential confounders such as air pollution, holidays, weekdays, etc. The study used a 0–3 day lag of the maximum AT and concluded that the 90th percentile of this exposure variable for the summer months, April to September, is the appropriate threshold value for the heat-morbidity function.3 We calculated the 90th percentile for the summer months for each grid cell from the climate data for the 1990s, yielding individual thresholds for each grid cell for each climate projection.

The PHEWE study calculated the relative risk (RR) coefficients for each of the 12 cities and then combined these into two metacoefficients, for north-continental cities 1.012 (95% CI 1.001 to 1.022) and Mediterranean cities 1.021 (95% CI 1.006 to 1.036), associated with a 1° increase above the temperature threshold. Metacoefficients were more suitable as they allowed calculation of the change in RHAs for countries with and without a city in the PHEWE study. We assigned the Mediterranean coefficient to Portugal and the Mediterranean countries. The rest of Europe was assigned the RR for the north-continental cities. Statistically significant coefficients were found for all ages and ages 75+ in the PHEWE study. Because the population data were not stratified by age, we used the PHEWE study coefficients for all ages.

Projections

The final data used in the impact calculations were based on the climate data grid with a resolution of 0.44°, resulting in 8075 grid cells over Europe. The population data, RR coefficients and baseline morbidity rates were projected for each grid cell. The countries within EU27 were grouped into four regions, northern, western, eastern and southern Europe, according to the United Nations classification scheme (http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#europe).

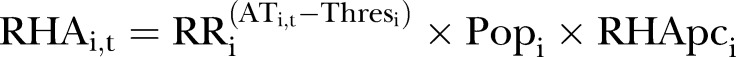

Thus, each grid cell includes (1) a daily time-series of 0–3 day lag maximum AT for each climate change projection, (2) a grid cell-specific temperature–morbidity threshold and a location-based RR coefficient and (3) population. For each grid cell, the AT was compared to the specific threshold for each day in the two time periods and risk estimates were calculated for each day. The expected number of daily RHAs in each cell was calculated using the population and the expected daily number of RHAs per capita, based on the national average of the grid cell. These were combined to calculate the excess number of RHAs as

|

where RHAi,t is the number of RHAs attributable to heat in grid cell i at time t, RRi the RR coefficient in grid cell i, (ATi,t−Thresi)+ the difference between the 0–3 lag AT and the threshold for grid cell i at time t if ATi,t were greater than the threshold and 0 otherwise, Popi and RHApci the population and expected number of RHAs per capita in grid cell i.

For each country, the estimated number of RHAs attributed to heat was calculated for each climate change projection for both the reference period and the future period. The estimated number of RHAs attributed to heat was then transformed into the proportion of the expected annual number RHAs for each country (data available from the authors). Mean estimates were calculated for each region for each climate change projection.

Sensitivity analysis

Because the study results could heavily depend on the RR coefficients and thresholds used, we assess whether the estimates appeared sensitive to the region-specific metacoefficients. We investigated the grids that contained the cities in the PHEWE study using both the location (Mediterranean or north-continental) and city-specific RR coefficients.3 We then compared the results with respect to the attributed proportion of RHAs and the proportional change in heat-related RHAs.

Results

The periods of warm days will increase in the future. For the cities included in the sensitivity analysis, the temperature threshold was exceeded annually, on average, by 20 days in the baseline period and 40 days in the future period.

In the future period, approximately 0.4% of the annual numbers of RHAs in Europe was estimated to be due to heat (table 1), based on the mean estimates over the climate change projections. In absolute terms, assuming all else as equal, this represents about 26 000 cases annually in Europe. This should be compared to the reference period where approximately 0.18% of all RHAs were attributed to heat or about 11 000 cases annually. Thus, the results suggest more than a relative doubling of the RHAs attributed to heat in Europe.

Table 1.

The estimated proportion of RHAs attributed to heat for each region. Intervals describe the highest and lowest national estimates in each region

| Region | 1981–2010 | 2021–2050 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe | 0.17% (0.16–0.19%) | 0.31% (0.29–0.35%) | 0.14% (0.11–0.17%) |

| Northern Europe | 0.13% (0.10–0.15%) | 0.27% (0.19–0.32%) | 0.14% (0.07–0.17%) |

| Southern Europe | 0.23% (0.18–0.26%) | 0.64% (0.42–0.68%) | 0.41% (0.23–0.44%) |

| Western Europe | 0.18% (0.16–0.20%) | 0.39% (0.34–0.45%) | 0.21% (0.17–0.26%) |

| EU27 | 0.18% (0.10–0.26%) | 0.40% (0.19–0.68%) | 0.21% (0.07–0.44%) |

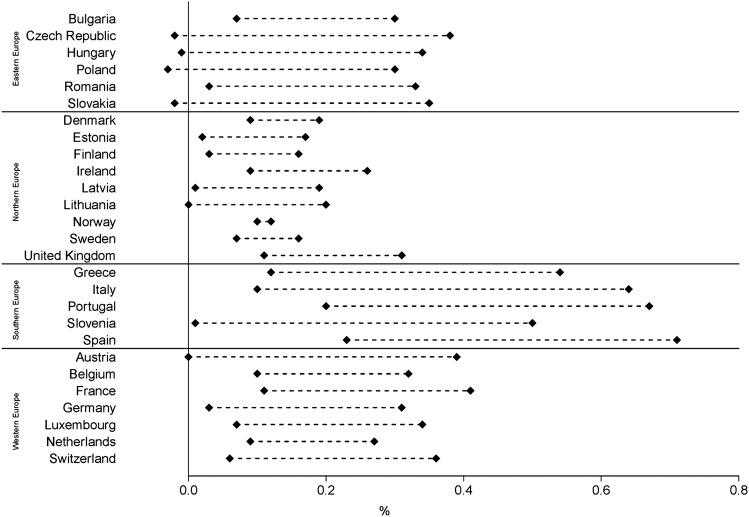

On the regional level, the five projections estimate increases in the number of heat-related RHAs for Europe (table 2). However, in one climate change projection, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia were estimated to have a decrease in heat-related RHAs (figure 1). The countries with the highest estimated increase also show the largest range between the highest and lowest estimates. The Scandinavian and Baltic countries show the smallest range between the highest and lowest estimates along with small increases of the mean estimates.

Table 2.

Future increase in heat-related RHAs based on the four climate models, under two emission scenarios, as the percentage of the annual expected number of RHAs in each region

| Climate model | CCSM3 (%) | ECHAM5 (%) | HadCM3 (%) | ECHAM4 (%) | ECHAM5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse gas scenario | A1B | A1B | A1B | A2 | A2 |

| Eastern Europe | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Northern Europe | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| Southern Europe | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.64 | 0.45 | 0.14 |

| Western Europe | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.06 |

| EU27 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.07 |

Figure 1.

The range of the absolute increase in RHAs attributed to heat between the two periods (1981–2010, 2021–2050) as a proportion of the annual expected number of RHAs for each of the 27 countries. The points show the highest and lowest estimates from four climate models under two emission scenarios.

There is variation among countries, with the largest increases in the southern European countries and the smallest increase in Eastern Europe (table 2). The relative change in the burden of RHAs in relation to the climate change scenarios investigated indicates a larger relative increase in Mediterranean countries (approximately three times) compared to northern European countries (approximately two times).

Sensitivity analysis

The calculations using the city-specific RR coefficients yielded a different proportion and number of estimated RHAs than the ones using the two metacoefficients, as expected. However, the relative changes in the number of hospital admissions attributed to heat between the two time periods were not affected by the change in the RR coefficients.

Discussion

The analysis estimates that the number of RHAs will increase in a warmer climate with more hot days. Heat-related RHAs were projected to increase two to three-fold in the future owing to climate change. However, the proportion of respiratory admissions attributed to heat would remain rather small. This projection is in line with the results of a recent study that estimates that respiratory admissions due to excessive heat in New York State will increase 2–6 times from the period 1991–2004 to the period 2080–2099.33

As most heat-related health outcomes occur during the warmest period of the year, presenting the increase as a change in the proportion of the total number of annual RHAs can underestimate the additional burden on the healthcare system during summer. As the threshold was exceeded for approximately 40 days in 1 year, an annual increase of 0.21% would result in a 1.9% increase on average during these 40 days. The annual numbers are used because the available baseline rates of RHAs are expressed as an annual average. Applying results to subnational scales could be inappropriate because national averages summarise over considerable heterogeneity.

The results suggest a larger impact from heat in southern Europe in the future period, centred on year 2035, than in the eastern and northern parts. This is in line with many climate change projections showing a larger relative increase in the number of extremely hot days in southern Europe compared with northern Europe.14 However, to some extent, this might also be explained by model bias for northern Europe introduced by the RCA3 model, where the model appears to underestimate temperature for the warmest days.19 This temperature bias is present in the reference period, future period and threshold values; therefore, the estimated numbers of RHAs from the two periods within each scenario are comparable, but comparisons within the same time period across scenarios may be inaccurate.

As the estimates are based on the population size in each grid cell, the added burden will be larger in countries with larger increases in temperatures in densely populated areas. Because the population of a city is considered to be a good predictor of the size of the urban heat island,34 an increase in the population living in urban areas will increase the numbers exposed and the temperature to which they are exposed. Heat islands increase temperatures in urbanised areas compared to surrounding areas, also reducing cooling during the night-time.35 These factors combined are likely to magnify the health burden during a heatwave.36 The spatial scale of the climate models makes them unable to take the urban heat island effect into account. Together with the urbanisation of Europe, this could potentially result in the underestimation of actual consequences/RHAs in the future period, because the same population size and composition were assumed in both periods. In addition, climate change is likely to increase ozone concentrations that would add an additional health burden for people at risk of respiratory diseases. The number of deaths and RHAs, due to a change in ozone, is expected to change in the future.37 A sensitivity analysis in the PHEWE study, however, showed that the exposure–response relationship for heat did not substantially differ between models taking ozone into account and models adjusting for NO2 alone.3

We used the same thresholds for the reference period and future period to isolate the effect of climate change. This would tend to overestimate the increased impact because there will undoubtedly be biological and/or social adaptations that will reduce future health temperature-related burdens. However, given the uncertainty of such adaptation effects, we choose to not incorporate such effects in the projections. Recent studies in the USA indicate that heat-related health burdens have decreased,38 indicating that some adaptation is taking place. An opposite trend appears to be occurring in Stockholm, with an increase in the risk of mortality associated with heat during the 1990s.39 A study looking at the impact of heat on mortality, before and after the implementation of a heat-warning system in Italy, shows that the effects of extreme heat can be reduced, whereas the effects of moderately increased average temperatures remain similar.40 The magnitude and the extent of future adaptation is, of course, highly uncertain and will vary between and within countries. Nevertheless, cities with higher thresholds seem to have higher risk ratio coefficients.3 41 In an effort to estimate future and presumably higher thresholds, one must also adjust the risk ratio coefficients. This would result in fewer days of elevated risk, but the risk increase on each occasion could be higher due to the higher RRs.

Table 2 shows how the results vary by global climate models and greenhouse gas scenarios. This study exemplifies the magnitude of the difference between projections made by a model with different initial conditions and between different models with the same initial conditions. The results indicate that the range of these estimates is large. The mean increase over the five projections, however, provides confidence that the number of RHAs will increase over Europe as the climate continues to change. The results from the different greenhouse gas emission scenarios are somewhat inconsistent with what is expected based on the characteristics of the scenarios. The scenario A2, which is considered a high-emission scenario, shows lower estimates of the increase in RHAs than the A1B scenario, which is considered a middle of the road scenario. This result is from the different regional climate models rather than the emission scenarios themselves. Up until 2050, the estimated temperature increase is actually estimated to be higher in A1B than A2 according to Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

To improve the estimates of the impact of heat on RHAs, detailed data on emergency room visits and admissions during summer are needed, such as the proportion of emergency department cases admitted to hospital and the death rate. A better understanding of vulnerable groups is needed, including how these groups could change over time. For example, the portion of the population aged over 65 will increase from 17% to 29%42 by 2050, significantly increasing the size of this vulnerable group. COPD is mainly a disease of the elderly. Persons suffering from COPD appear to be especially vulnerable to heat,43 and the incidence of COPD is likely to increase44 with the consequence that the health impact of heat may increase in future years. This study was limited to estimating the impact on the total population because few age-specific relationships were reported and because age-stratified data were only available on a coarser spatial scale than the climate data, which would reduce the benefits of having spatial climate data. When spatial population data, such as the Eurostat data, have a finer age stratification, a more detailed assessment will be possible.

Normal weather patterns in the future will be different than those existing today, both for average temperature and extreme weather events. As the number of heat-related RHAs is expected to increase on the subcontinental scale, additional national or regional projections of the future health burden from heat are needed that will take into account possible changes in exposure and vulnerability.

Conclusions

Projected changes in temperature and the number of extreme heat events with climate change could substantially influence respiratory morbidity across Europe. Analyses projected that both the future proportion of annual RHAs attributed to heat and the relative change in heat-related RHAs will be largest in southern Europe, where they are expected to nearly triple. Eastern Europe can expect the smallest increase in heat-related RHAs, where they are estimated to approximately double. For all of Europe, the number of respiratory heat-related hospital admissions is projected to be 26 000 annually in the future period (2021–2050) compared with 11 000 in the reference period (1981–2010). The estimates presented rely on the assumption that no additional adaptation occurs. Future studies should elaborate and quantify the possible effects of different adaptation assumptions applied to regional conditions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CÅ, BF (PI) and HO planned and designed the study. GS was responsible for preparing the meteorological model data, and HO for acquiring the population and health data. CÅ was responsible for carrying out the statistical analysis and producing graphs and tables. All authors interpreted the results. The initial draft was prepared by CÅ and BF, and the manuscript was finalised and approved by all the authors.

Funding: This work was supported by the EU-funded Climate-Trap project (contract EAHC20081108) and by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency through the research programme CLEO—Climate Change and Environmental Objectives.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The specific estimates for each of the EU27 countries, for each of the climate projections, are available after contact with the corresponding author at christofer.astrom@envmed.umu.se.

References

- 1.Loddenkemper R, Gibson G, Sibille Y. European lung white book. Sheffield: European Respiratory Society/European Lung Foundation, 2003:1–182 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayres JG, Forsberg B, Annesi-Maesano I, et al. Climate change and respiratory disease: European Respiratory Society position statement. Eur Respir J 2009;34:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelozzi P, Accetta G, De Sario M, et al. High temperature and hospitalizations for cardiovascular and respiratory causes in 12 European cities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:383–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocklov J, Forsberg B. Comparing approaches for studying the effects of climate extremes—a case study of hospital admissions in Sweden during an extremely warm summer. Glob Health Action 2009;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovats RS, Hajat S. Heat stress and public health: a critical review. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:41–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowlton K, Rotkin-Ellman M, King G, et al. The 2006 California heat wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:61–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rey G, Jougla E, Fouillet A, et al. The impact of major heat waves on all-cause and cause-specific mortality in France from 1971 to 2003. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2007;80:615–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin S, Luo M, Walker RJ, et al. Extreme high temperatures and hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Epidemiology 2009;20:738–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsberg B, Braback L, Keune H, et al. An expert assessment on climate change and health—with a European focus on lungs and allergies. Environ Health 2012;11(Suppl 1):S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye X, Wolff R, Yu W, et al. Ambient temperature and morbidity: a review of epidemiological evidence. Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenza JC, McCullough JE, Flanders WD, et al. Excess hospital admissions during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Am J Prev Med 1999;16:269–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhainaut JF, Claessens YE, Ginsburg C, et al. Unprecedented heat-related deaths during the 2003 heat wave in Paris: consequences on emergency departments. Crit Care 2004;8:1–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IPCC Climate change 2007—the physical science basis: Working Group I contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge: and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikulin G, Kjellström E, Hansson ULF, et al. Evaluation and future projections of temperature, precipitation and wind extremes over Europe in an ensemble of regional climate simulations. Tellus A 2011;63:41–55 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schar C, Vidale PL, Luthi D, et al. The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 2004;427:332–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stott PA, Stone DA, Allen MR. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 2004;432:610–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebetez M, Dupont O, Giroud M. An analysis of the July 2006 heatwave extent in Europe compared to the record year of 2003. Theor Appl Climatol 2009;95:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barriopedro D, Fischer EM, Luterbacher J, et al. The hot summer of 2010: redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 2011;332:220–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samuelsson P, Jones CG, Willen U, et al. The Rossby Centre Regional Climate model RCA3: model description and performance. Tellus ser A—Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 2011;63:4–23 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins WD, Bitz CM, Blackmon ML, et al. The community climate system model version 3 (CCSM3). J Climate 2006;19:2122–43 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roeckner E, Bäuml G, Bonaventura L, et al. The atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM 5. PART I: model description. Hamburg: MPI für Meteorologie, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johns TC, Durman CF, Banks HT, et al. The new Hadley Centre Climate Model (HadGEM1): evaluation of coupled simulations. J Climate 2006;19:1327–53 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roeckner E, Arpe K, Bengtsson L, et al. The atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM-4: Model description and simulation of present-day climate. Hamburg: MPI für Meteorologie, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakicenovic N, Alcamo J, Davis G, et al. Special report on emissions scenarios: a special report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Richland, WA: Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (US), 2000:239–92. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballester J, Robine JM, Herrmann FR, et al. Long-term projections and acclimatization scenarios of temperature-related mortality in Europe. Nat Commun 2011;2:358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knowlton K, Lynn B, Goldberg RA, et al. Projecting heat-related mortality impacts under a changing climate in the New York City region. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2028–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baccini M, Kosatsky T, Analitis A, et al. Impact of heat on mortality in 15 European cities: attributable deaths under different weather scenarios. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beguin A, Hales S, Rocklov J, et al. The opposing effects of climate change and socio-economic development on the global distribution of malaria. Global Environ Change-Hum Policy Dimens 2011;21:1209–14 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldewijk KK, Beusen A, Janssen P. Long-term dynamic modeling of global population and built-up area in a spatially explicit way: HYDE 3.1. Holocene 2010;20:565–73 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawrence MG. The relationship between relative humidity and the dewpoint temperature in moist air: a simple conversion and applications. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 2005;86:225–33 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons KC. Human thermal environments: the effects of hot, moderate, and cold environments on human health, comfort, and performance: Taylor & Francis, London, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steadman RG. A Universal scale of apparent temperature. J Clim Appl Meteorol 1984;23:1674–87 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin S, Hsu WH, Van Zutphen AR, et al. Excessive heat and respiratory hospitalizations in New York state: estimating current and future public health burden related to climate change. Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:1571–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oke TR. City size and the urban heat island. Atmospheric Environ (1967) 1973;7:769–79 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmer B, Thorsson S, Eliasson I. Cooling rates, sky view factors and the development of intra-urban air temperature differences. Geografiska Annaler: Series A Phys Geogr 2007;89:237–48 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholls N, Skinner C, Loughnan M, et al. A simple heat alert system for Melbourne, Australia. Int J Biometeorol 2008;52:375–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orru H, Andersson C, Ebi KL, et al. Impact of climate change on ozone related mortality and morbidity in Europe. Eur Respir J 2012. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis RE, Knappenberger PC, Michaels PJ, et al. Changing heat-related mortality in the United States. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111:1712–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocklov J, Forsberg B, Meister K. Winter mortality modifies the heat-mortality association the following summer. Eur Respir J 2009;33:245–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schifano P, Leone M, De Sario M, et al. Changes in the effects of heat on mortality among the elderly from 1998–2010: results from a multicenter time series study in Italy. Environ Health 2012;11:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baccini M, Biggeri A, Accetta G, et al. Heat effects on mortality in 15 European cities. Epidemiology 2008;19:711–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giannakouris K. Ageing characterises the demographic perspectives of the European societies. Statistics in focus 2008;72:2008 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz J. Who is sensitive to extremes of temperature? A case-only analysis. Epidemiology 2005;16:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.