Abstract

Despite the large collection of selectable marker genes available for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, marker availability can still present a hurdle when dozens of genetic manipulations are required. Recyclable markers, counterselectable cassettes that can be removed from the targeted genome after use, are therefore valuable assets in ambitious metabolic engineering programs. In the present work, the new recyclable dominant marker cassette amdSYM, formed by the Ashbya gossypii TEF2 promoter and terminator and a codon-optimized acetamidase gene (Aspergillus nidulans amdS), is presented. The amdSYM cassette confers S. cerevisiae the ability to use acetamide as sole nitrogen source. Direct repeats flanking the amdS gene allow for its efficient recombinative excision. As previously demonstrated in filamentous fungi, loss of the amdS marker cassette from S. cerevisiae can be rapidly selected for by growth in the presence of fluoroacetamide. The amdSYM cassette can be used in different genetic backgrounds and represents the first counterselectable dominant marker gene cassette for use in S. cerevisiae. Furthermore, using astute cassette design, amdSYM excision can be performed without leaving a scar or heterologous sequences in the targeted genome. The present work therefore demonstrates that amdSYM is a useful addition to the genetic engineering toolbox for Saccharomyces laboratory, wild, and industrial strains.

Keywords: counter-selectable marker, dominant marker, scarless marker removal, acetamidase, serial gene deletion, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Introduction

The past decade has been marked by the construction of complex cell factories resulting from dozens of genetic manipulations and leading to remarkable new capabilities. For instance, the industrial and model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been engineered to produce the anti-malaria drug precursor artemisinic acid (Ro et al., 2006), hydrocortisone (Szczebara et al., 2003), and cineole (Ignea et al., 2011), among others. The ever-increasing demand for cheap and sustainable production of complex molecules combined with its attractiveness as a host for pathway engineering will inevitably intensify the exploitation of S. cerevisiae as cell factory in the future (Hong & Nielsen, 2012). Also, in fundamental yeast research, extensive genetic manipulation is necessary, for instance to unravel complex transport systems (Wieczorke et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 2011) and regulatory networks (Baryshnikova et al., 2010). A common and critical feature for all these genetic manipulations is the requirement of selectable markers that enable the selection of mutants carrying the desired genetic modifications. Despite the relatively large number of selection markers available for S. cerevisiae (Table 1), the construction of multiple successive genetic modifications remains a challenge as the number of genetic manipulations typically equals the number of selection markers introduced in the host. Selection markers can be classified in two main categories: auxotrophic markers, which restore growth of specific mutants, and dominant markers, which confer completely new functions to their host. Both types suffer from substantial drawbacks. The use of auxotrophic markers is restricted to auxotrophic strains, that is, strains carrying mutations in one gene leading to a strict requirement for a specific nutrient (Pronk, 2002). This constrain is augmented for industrial strains that are typically prototrophic and for which the aneuploidy or polyploidy makes the construction of auxotrophic strains a laborious task (Puig et al., 1998). The expression in a single strain of multiple dominant marker genes, under the control of strong promoters, may result in protein burden and other negative effects on host strain physiology (Gopal et al., 1989; Nacken et al., 1996). Additionally, for industrial strains dedicated to food applications such as the production of nutraceuticals, the lack of heterologous DNA is highly desired.

Table 1.

Different selectable markers used in laboratory and industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

| Marker gene | Mode of action | Recyclable/Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic markers | |||

| URA3 | Repairs uracil deficiency | Yes/negative selection with 5-FOA | Alani et al. (1987), Langlerouault & Jacobs (1995) |

| KlURA3 | Repairs uracil deficiency | Yes/negative selection with 5-FOA | Shuster et al. (1987) |

| CaURA3 | Repairs uracil deficiency | Yes/negative selection with 5-FOA | Losberger & Ernst (1989) |

| HIS3 | Repairs histidine deficiency | No/– | Wach et al. (1997) |

| HIS5 | Repairs histidine deficiency | No/– | Wach et al. (1997) |

| LEU2 | Repairs leucine deficiency | No/– | Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| KlLEU2 | Repairs leucine deficiency | No/– | Zhang et al. (1992) |

| LYS2 | Repairs lysine deficiency | Yes/negative selection with alpha-aminoadipate | Chattoo et al. (1979) |

| TRP1 | Repairs tryptophan deficiency | No/– | Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| ADE1 | Repairs adenine deficiency | No/– | Nakayashiki et al. (2001) |

| ADE2 | Repairs adenine deficiency | No/– | Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| MET15 | Repairs methionine deficiency | Yes/negative selection with methyl-mercury | Singh & Sherman (1974), Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| Dominant markers | |||

| KanMX | Resistance to G418 | No/– | Wach et al. (1994) |

| ble | Resistance to phleomycin | No/– | Gatignol et al. (1987) |

| Sh ble | Resistance to Zeocin | No/– | Drocourt et al. (1990) |

| hph | Resistance to hygromycin | No/– | Gritz & Davies (1983) |

| Cat | Resistance to chloramphenicol | No/– | Hadfield et al. (1986) |

| CUP1 | Resistance to Cu2+ | No/– | Henderson et al. (1985) |

| SFA1 | Resistance to formaldehyde | No/– | Van den Berg & Steensma (1997) |

| dehH1 | Resistance to fluoroacetate | No/– | Van den Berg & Steensma (1997) |

| PDR3-9 | Multi drug resistance | No/– | Lackova & Subik (1999) |

| AUR1-C | Resistance to aureobasidin | No/– | Hashida-Okado et al. (1998) |

| nat | Resistance to nourseothricin | No/– | Goldstein & McCusker (1999) |

| CYH2 | Resistance to cycloheximide | No/– | Delpozo et al. (1991) |

| pat | Resistance to bialaphos | No/– | Goldstein & McCusker (1999) |

| ARO4-OFP | Resistance to o-Fluoro-DL-phenylalanine | No/– | Cebollero & Gonzalez (2004) |

| SMR1 | Resistance to sulfometuron methyl | No/– | Xie & Jimenez (1996) |

| FZF1-4 | Increased tolerance to sulfite | No/– | Cebollero & Gonzalez (2004) |

| DsdA | Resistance to d-Serine | No/– | Vorachek-Warren & McCusker (2004) |

While protein burden might be avoided by expressing marker genes from inducible promoters (Suzuki et al., 2011), many inducible promoters are notoriously leaky (Agha-Mohammadi et al., 2004) and therefore only partly address the problem. A good alternative resides in the use of recyclable markers. Marker recycling was first shown with URA3 (Alani et al., 1987). Loss of URA3, encoding orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis, is lethal in uracil-free media. Since its discovery, URA3 has become a very popular auxotrophic selection marker. This popularity mainly originates from the ability of URA3 to be counter-selected in the presence of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), which is converted to a toxic compound (5-fluoro-UMP) by Ura3p. Indeed, when the URA3 marker is flanked by direct repeats, cultivation on 5-FOA enables the efficient selection of strains in which URA3 has been excised via mitotic recombination. URA3 can therefore be re-used for further modifications (Alani et al., 1987; Langlerouault & Jacobs, 1995). Besides the obvious need for auxotrophic strains, another drawback of the most frequently used URA3 cassette is that sequences (or scars) are left after marker removal. Commonly, the bacterial sequence hisG is present as direct repeat. However, repeated use of URA3 cassettes carrying hisG increases the probability of mistargeted integrations (Davidson & Schiestl, 2000). An alternative to hisG is the creation of direct repeats upon integration using sequences already present in the host genome, generating seamless marker removal (Akada et al., 2006). Similar to URA3, two other auxotrophic markers MET15 and LYS2 can be counter-selected in the presence of methyl-mercury (Singh & Sherman, 1974) and alpha-aminoadipate (Chattoo et al., 1979), respectively. Nevertheless, their use is limited by the same complications described for URA3.

A successful attempt to recycle virtually any desired marker was the development of the bacteriophage-derived LoxP-Cre recombinase system (Hoess & Abremski, 1985; Sauer, 1987; Guldener et al., 1996, 2002). Exploiting the site-specific activity of the Cre recombinase, this system is used to efficiently remove markers by flanking them with the targeted LoxP sequence. This system exhibits two major limitations: (1) it requires the expression of a plasmid-borne recombinase and thereby necessitates an additional selection marker or extensive screening (Schorsch et al., 2009); and (2) the repeated use of this system causes major chromosomal rearrangements (Delneri et al., 2000; E. Boles, pers. commun.).

The Aspergillus nidulans amdS gene encoding acetamidase has been successfully used as dominant ‘gain of function’ selection marker in different filamentous fungi and the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis (Kelly & Hynes, 1985; Beri & Turner, 1987; Yamashiro et al., 1992; Swinkels et al., 1997; Selten et al., 2000; van Ooyen et al., 2006; Read et al., 2007; Ganatra et al., 2011). Although Selten et al. (2000) suggested that amdS could be used for selection in S. cerevisiae, this statement was not further supported by experimental evidence. Acetamidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of acetamide to acetate and ammonia, thus conferring the ability to the host cell to use acetamide as sole nitrogen or carbon source (Corrick et al., 1987; Hynes, 1994). Similar to URA3, amdS is a recyclable marker that can be counter-selected by growth on media containing the acetamide homologue fluoroacetamide, which is converted by acetamidase to the toxic compound fluoroacetate (Apirion, 1965; Hynes & Pateman, 1970).

This study evaluates the use of the new dominant marker module amdSYM for S. cerevisiae and demonstrates its efficiency for sequentially introducing multiple gene deletions in yeast. Availability of this dominant, counterselectable marker cassette to the yeast research community should facilitate rapid introduction of multiple genetic modifications into any laboratory, wild, and industrial Saccharomyces strains.

Material and methods

Strains and media

Propagation of plasmids was performed in chemically competent Escherichia coli DH5α according to manufacturer instructions (Z-competent™ transformation kit; Zymo Research, CA). All yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Under nonselective conditions, yeast was grown in complex medium (YPD) containing 10 g L−1 yeast extract, 20 g L−1 peptone, and 20 g L−1 glucose. Synthetic media (SM) containing 3 g L−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 5 g L−1 (NH4)2SO4, 1 mL L−1 of a trace element solution as previously described (Verduyn et al., 1992), 1 mL L−1 of a vitamin solution (Verduyn et al., 1992) were used. When amdSYM was used as marker, (NH4)2SO4 was replaced by 0.6 g L−1 acetamide as nitrogen source and 6.6 g L−1 K2SO4 to compensate for sulfate (SM-Ac). Recycled markerless cells were selected on SM containing 2.3 g L−1 fluoroacetamide (SM-Fac). SM, SM-Ac, and SM-Fac were supplemented with 20 mg L−1 adenine and 15 mg L−1 l-canavanine sulfate when required. In all experiments, 20 g L−1 of glucose was used as carbon source. The pH in all the media was adjusted to 6.0 with KOH. Solid media were prepared by adding 2% agar to the media described above.

Table 2.

Primers used for RT–qPCR, product sizes and efficiency values

| Strain | Genotype | References |

|---|---|---|

| CEN.PK113-7D | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 | van Dijken et al. (2000), Entian & Kotter (2007), Nijkamp et al. (2012) |

| CEN.PK113-5D | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 ura3-52 | van Dijken et al. (2000), Entian & Kotter (2007) |

| CBS8066 | MATa/α HO/ho | Centraal Bureau voor Schimmel-cultures, http://www.cbs.knaw.nl; CBS, Den Haag, the Netherlands |

| YSBN | MATa/α ho::Ble/ho::HphMX4 | Canelas et al. (2010) |

| S288c | MATα SUC2 gal2 mal mel flo1 flo8-1 hap1 ho bio1 bio6 | Mortimer & Johnston (1986) |

| CBS1483 | Saccharomyces pastorianus | Dunn & Sherlock (2008) |

| Scottish Ale | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Gift from Dr. JM Geertman (Heineken Supply Chain, Zoeterwoude, the Netherlands) |

| CBS12357 | Saccharomyces eubayanus sp.nov | Libkind et al. (2011) |

| IME141 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 ura3-52 pAG426GPD (2μ URA3 TDH3pr-CYC1ter) | This study |

| IME142 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 ura3-52 pUDE158 (2μ URA3 TDH3pr-amdS-CYC1ter) | This study |

| IMX168 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 can1Δ::amdSYM ADE2 | This study |

| IMX200 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 can1Δ ADE2 | This study |

| IMX201 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 can1Δ ade2Δ::amdSYM | This study |

| IMX206 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 can1Δ ade2Δ | This study |

| IMK468 | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 hxk1Δ::loxP-amdSYM-loxP | This study |

| IMK470 | CBS1483 Sc-hxk1Δ::loxP-amdSYM-loxP | This study |

| IMK473 | Scottish Ale Sc-aro80Δ::loxP-amdSYM-loxP | This study |

| IMK474 | CBS12357 Seub-aro80Δ::loxP-amdSYM-loxP | This study |

amdSYM and plasmid construction

A codon-optimized [JCat, http://www.jcat.de/, (Grote et al., 2005)] version of A. nidulans amdS flanked by SalI and XhoI restriction sites and attB1 and attB2 recombination sites (Accession number: JX500098) was synthesized at GeneArt AG (Regensburg, Germany) and cloned into the vector pMA (GeneArt AG) generating the plasmid pUD171. The amdS gene was transferred into the destination plasmid pAG426GPD (Alberti et al., 2007) by LR recombination reaction according to the manufacturer recommendations (Invitrogen, CA) yielding the plasmid pUDE158.

The Ashbya gossypii TEF2ter from pUG6 (Guldener et al., 1996, 2002) was amplified, and the restriction sites XhoI and KpnI incorporated with the primers p1FW and p1RV and Phusion™ Hot Start Polymerase (Finnzymes, Vantaa, Finland). Restriction with XhoI and KpnI and ligation of the amplified fragment and the vector p426TEF (Mumberg et al., 1995) resulted in the replacement of the CYC1ter of p426TEF for (A.g.) TEF2ter. The generated vector was termed p426TEF-TEF(t).

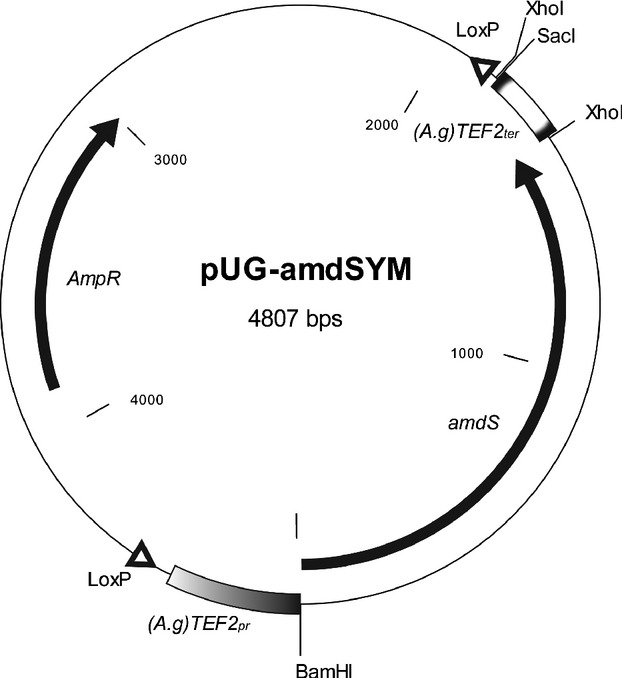

Primers amdSBFW and amdSXRV and Phusion™ Hot Start Polymerase (Finnzymes) were used to amplify amdS and to incorporate BamHI and XhoI sites using pUD171 as template. After digestion with the corresponding enzymes, the gene was cloned into the vector p426TEF-TEF(t) generating the plasmid pUD184. Using primers amdSBFW and amdSSRV, containing BamHI and SacI restriction sites, respectively, and Phusion™ Hot Start Polymerase (Finnzymes), the gene amdS together with A. gossypii TEF2 terminator was amplified from pUD184. To incorporate BamHI and SacI restriction sites in pUG6, the complete plasmid backbone was amplified by PCR with the primers SpUGFW and pUGBRV and Phusion™ Hot Start Polymerase (Finnzymes). Digestion with BamHI and SacI of the modified pUG6 and the amdS-(A.g).TEF2ter and ligation led to the construction of pUG-amdSYM (Fig. 1). All primers and their sequences are listed in Table 3. The plasmid pUG-amdSYM is available to the research community at Euroscarf (http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/fb15/mikro/euroscarf/) with the accession number: P30669.

Fig 1.

pUG-amdSYM map. pUG-amdSYM was constructed by replacing the marker KanMX in pUG6 for a codon-optimized version of Aspergillus nidulans amdS. The plasmid kept all features present in the pUG family (Guldener et al., 1996, 2002).

Table 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence 5′–3′*,† |

|---|---|

| Plasmid construction | |

| amdSBFW | GGGGGATCCATGCCACAATCTTGGGAAGAA |

| amdSXRV | GGGCTCGAGTTATGGAGTAACAACG |

| amdSSRV | GGGGAGCTCCAGTATAGCGACCAGCATTC |

| p1FW | CCGCTCGAGCAGTACTGACAATAAAAAGATTC |

| p1RV | GCGGTACCCAGTATAGCGACCAGCATTC |

| pUGBRV | GGGGGATCCTTGTTTATGTTCGGATGTGATGTG |

| SpUGFW | GGGCGAGCTCTCGAGAACCCTTAA |

| Deletion cassette construction | |

| CdcamdSFW | TCAGACTTCTTAACTCCTGTAAAAACAAAAAAAAAAAAAGGCATAGCAATCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC |

| CdcamdSRV | ATGCGAAATGGCGTGGGAATGTGATTAAAGGTAATAAAACGTCATATCTAAGAACTCTGAAATAAACTTTCGATTGACGACAGATTGAAAGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG |

| AdcamdSFW | TACTATAACAATCAAGAAAAACAAGAAAATCGGACAAAACAATCAAGTATCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC |

| AdcamdSRV | TCATTTTATAATTATTTGCTGTACAAGTATATCAATAAACTTATATATTAGGATGTACTTAGAAGAGAGATCCAACGATTTTACGCACCAGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG |

| HdcamdSFW | AAACTCACCCAAACAACTCAATTAGAATACTGAAAAAATAAGATGATGACAAGAGGGTCGAACTCCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC |

| HdcamdSRV | AGGGAGGGAAAAACACATTTATATTTCATTACATTTTTTTCATTAGCCTAAGTCGTAATTGAGTCGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG |

| ScHdcamdSFW | CTTCTTATGCCCCTGAACCC |

| ScHdcamdSRV | CTATCCTACGACTTTCTCCCTC |

| ScARO80dcamdSFW | AGTTAGTCGTAGGAATATATGATCCACGCATAATAAGGTTACATTAAGCACTGCTTTATCCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC |

| ScARO80dcamdSRV | CTTTGTATTTAAAATCATTTTTACGAATAGTGCGGTTGTCTTGGTTGATGACGTAATTCTGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG |

| ScARO80g5′FW | CACTACCAAAGCCAAATCAGAC |

| ScARO80g5′RV | GATAAAGCAGTGCTTAATGTAACC |

| ScARO80g3′FW | AGAATTACGTCATCAACCAAGAC |

| ScARO80g3′RV | AGCGTAGCTTGCACTACTAG |

| SeubARO80dcamdSFW | AGCAAGCTAGTCAAAATATTTGCTCTCCGCATGATATAATTACTTTCAGTATCGTTGTCCCCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC |

| SeubARO80dcamdSRV | TAGTAATCAATCATTTATCTAATTAAACATTCCTTTTCTCTAATTTTATGTGTGAGGGGCGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG |

| SeubARO80g5′FW | GACATTGATGACAATGGTAGTG |

| SeubARO80g5′RV | GGACAACGATACTGAAAGTAAT |

| SeubARO80g3′FW | GCCCCTCACACATAAAATTAGAG |

| SeubARO80g3′RV | GTGTGGCTTGTACCACAAGA |

| Deletion/Marker removal confirmation | |

| CdcFW | CGGGAGCAAGATTGTTGTG |

| CdcRV | GGTTGCGAACAGAGTAAACC |

| AdcFW | AAAGGACACCTGTAAGCGTTG |

| AdcRV | AGCATTTCATGTATAAATTGGTGCG |

| HdcFW | CCTTAGGACCGTTGAGAGGAATAG |

| HdcRV | GACCGCAAAAAAAACATAAGGG |

| ScARO80dcFW | TGATCCCGATACTGGAAATCAA |

| amdSdcRV | CGACCAGCATTCACATACGA |

| ScARO80gRV | TTCATCCTATCTGAACAGAATAC |

| SbARO80dcFW | GTCATGCAGGCTCTTCATTG |

| SbARO80gRV | TATCCCTCACGTGAATTTAAACC |

| Sequencing | |

| C-FW | ATCACTTACTGGCAAGTGCG |

| C-RV | ATCAGTTGTGCCTGGAAAAG |

| A-FW | AACGCCGTATCGTGATTAAC |

| A-RV | GGACACTTATATGTCGAGCAAGA |

The sequences underlined indicate the position of the introduced restriction.

†The sequences in bold indicate the direct repeats used to excise the marker gene upon counter selection.

Deletion cassette construction

Deletion cassettes were constructed by PCR using Phusion™ Hot Start Polymerase (Finnzymes) and following manufacturer recommendations. Primers used for repeated gene deletions had a similar design described as follows. Forward primers contain two cores: (1) a 50- to 55-bp sequence homologous to the region upstream the gene to delete and (2) the sequence 5′-CAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC-3′ that binds to the region upstream the A. gossypii TEF2 promoter in pUG-amdSYM. Reverse primers contained three cores: (1) a 50- to 55-bp sequence homologous to the region downstream the gene to be deleted, (2) a 40-bp sequence homologous to the region upstream the targeted region, and (3) the sequence 5′-GCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG-3′ that binds downstream the A. gossypii TEF2 terminator in pUG-amdSYM. CAN1 and ADE2 deletion cassettes were constructed using the primer pairs CdcamdSFW and CdcamdSRV, and AdcamdSFW and AdcamdSRV, respectively (Table 3).

To construct the deletion cassette targeting S. cerevisiae HXK1 (Sc.HXK1), primers HdcamdSFW and HdcamdSRV and the template pUG-amdSYM were used. The constructed cassette was used to generate the strain IMK468 derived from CEN.PK113-7D. Genomic DNA of IMK468 was used as template for primers ScHdcamdSFW and ScHdcamdSRV. The resulting cassette contained 500-bp homologous sequences upstream and downstream of the Sc.HXK1 gene and was used for the deletion of Sc.HXK1 in the Saccharomyces pastorianus lager brewing strain CBS1483. The construction of the deletion cassette corresponding to Sc.ARO80 allele for the S. cerevisiae Scottish Ale strain was performed according to the two-step fusion protocol (Amberg et al., 1995) with the primers ScARO80dcamdSFW and ScARO80dcamdSRV to amplify amdSYM from pUG-amdSYM, and ScARO80g5′FW, ScARO80g5′RV, ScARO80g3′FW, and ScARO80g3′RV to generate the 500-bp sequence homologous to upstream and downstream sections of Sc.ARO80, and genomic DNA from CBS1483 was used as template. The same approach was taken for the deletion of Saccharomyces eubayanus ARO80 (Sb.ARO80) in CBS12357 using the primer pairs SeubARO80dcamdSFW/SeubARO80dcamdSRV, SeubARO80g5′FW/SeubARO80g5′RV, and SeubARO80g3′FW/SeubARO80g3′RV. All primers and their sequences are listed in Table 3.

Selection and marker recycling

Yeast transformations were performed using the lithium acetate protocol (Gietz & Woods, 2002). Integration of the deletion cassettes into the yeast genome was selected by plating the transformation mix on SM-Ac. Targeted integration was verified by PCR with the primer pairs CdcFW/CdcRV, AdcFW/AcdRV, HdcFW/HdcRV, ScARO80dcFW/amdSdcRV, ScARO80dcFW/ScARO80gRV, SbARO80dcFW/amdSdcRV, SbARO80dcFW/SbARO80gRV and, when applicable, by transferring single colonies to SM plates containing 15 mg L−1 l-canavanine or by screening for colony pigmentation. A small fraction of single colony was resuspended in 15 μL of 0.02 N NaOH; 2 μL of this cell suspension was used as template for the PCR that was performed using DreamTaq PCR master mix (Fermentas GmbH, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) following the manufacturer recommendations. Marker removal was achieved by growing cells overnight in liquid YPD and transferring 0.2 mL to a shake flask containing 100 mL of SM-FAc. Marker-free single colonies were obtained by plating 0.1 mL of culture on SM-Fac solid media and confirmed by PCR with the primer pairs CdcFW/CdcRV or AdcFW/AcdFW. All cultures were incubated at 30 °C. To confirm that only endogenous sequences were present after marker removal, long run sequencing (Baseclear, Leiden, the Netherlands) was performed using the primers C-FW and C-RV for the CAN1 locus and A-FW and A-RV for ADE2 locus of the marker-free strain IMX206.

Results and discussion

Expression of amdS in S. cerevisiae confers the ability to grow on acetamide as sole nitrogen source

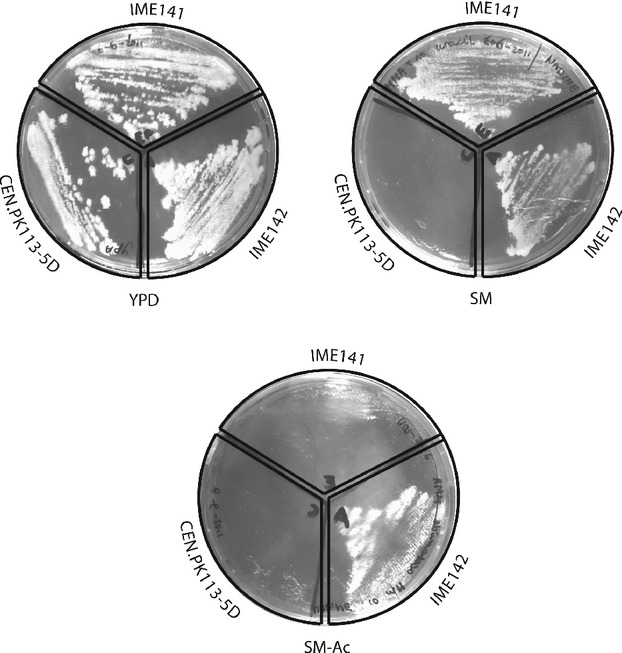

Although the yeast putative amidase gene AMD2 is similar (57.2% similarity and 33.2% identity) to A. nidulans amdS (Chang & Abelson, 1990), there is no report demonstrating acetamidase activity in wild-type S. cerevisiae or on growth of budding yeast on acetamide as sole nitrogen or carbon source. Expression of amdS in S. cerevisiae is therefore expected to bring a new function in this yeast by enabling its growth on acetamide as sole nitrogen source. Although the Aspergillus nidulans amdS promoter is able to drive the expression of genes in S. cerevisiae, this is only possible under carbon-limited conditions (Bonnefoy et al., 1995). Therefore, a codon-optimized amdS sequence was cloned under the control of the strong, constitutive TDH3 promoter in the plasmid pUDE158.

The plasmid pUDE158, containing amdS, and the empty vector pAG426GPD were transformed into CEN.PK113-5D, generating strains IME142 and IME141, respectively. Expression of the acetamidase gene in S. cerevisiae (strain IME142) conferred growth with acetamide as sole nitrogen source, while the control strain (strain IME141) was unable to grow (Fig. 2). Additionally, the inability of IME142 to grow on acetamide upon loss of amdS by counter selection with 5-FOA of pUDE158 confirmed that growth on acetamide was fully amdS dependent (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Growth of strains from the CEN.PK family on acetamide as sole nitrogen source. Expression of amdS on the multicopy plasmid pUDE158 conferred to Saccharomyces cerevisiae the ability to grow on acetamide as sole nitrogen source. The strains CEN.PK113-5D (ura3-52), IME141 [ura3-52 pAG426GPD (2μ URA3 TDH3pr-CYC1ter)], and IME142 [ura3-52 pUDE158 (2μ URA3 TDH3pr-amdS-CYC1ter)] were grown on YPD, SM and SM-Ac media and incubated at 30 °C. The plates were read after 3 days.

Plasmids and deletion cassettes construction

The coding sequence of the A. nidulans amdS gene, codon-optimized for expression in S. cerevisiae and flanked by the A. gossypii TEF2 promoter and terminator, was cloned into the vector pUG6 (Guldener et al., 1996, 2002) by replacing the KanMX gene, resulting in the plasmid pUG-amdSYM (Fig. 1). The resulting amdSYM module only contained heterologous sequences, thereby reducing the probability of mistargeted integration (Wach et al., 1994). The pUG-amdSYM plasmid can be easily used as template for deletion cassettes containing the new marker module amdSYM and was used for the construction of all deletion cassettes used in this study.

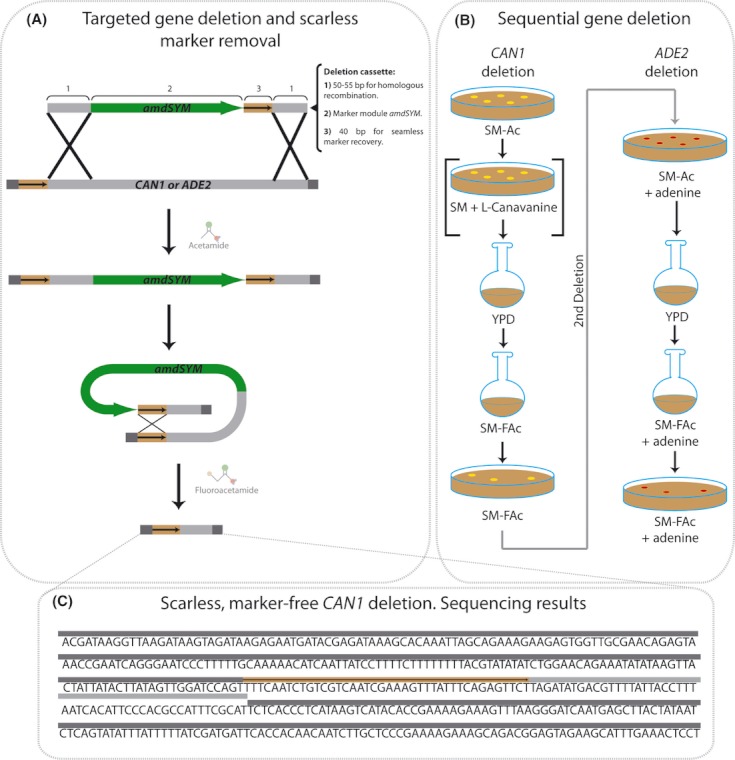

The deletion cassettes contained three major regions (Fig. 3A): (1) a 50- to 55-bp sequence homologous to the upstream part of the gene to be deleted, including the start codon, and a 50- to 55-bp sequence homologous to the downstream part of the gene to be deleted, including the stop codon. These regions were used for targeted homologous recombination (Baudin et al., 1993): (2) the amdSYM marker and (3) a 40-bp sequence homologous to the region upstream of the targeted locus to create direct repeats in the host genome upon integration, thereby enabling scarless marker excision (Akada et al., 2006; Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Sequential gene deletions methodology. (A) Cassette design for targeted gene deletion and seamless marker removal. (B) Experimental procedure for the sequential deletion of CAN1 and ADE2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by amdSYM recycling. (C) Sequencing results of the CAN1 loci of the marker-free IMX206 (can1Δ ade2Δ).

Repeated gene deletions in S. cerevisiae using amdSYM

To evaluate whether the new marker amdSYM was suitable for repeated gene knock-out in S. cerevisiae, it was attempted to sequentially delete two genes in the laboratory strain CEN.PK113-7D and, after marker recycling, to construct a marker-free and scarless double-deletion strain. CAN1 and ADE2 were selected for this proof-of-principle experiment because the phenotype caused by CAN1 or ADE2 deletion can be visually screened, giving a fast preliminary evaluation of targeted integration. CAN1 encodes an l-arginine transporter that can also import the toxic compound l-canavanine. Mutants with disrupted CAN1 are able to grow in media containing l-canavanine (Ahmad & Bussey, 1986). ADE2 codes for the enzyme phosphoribosylaminoimidazol carboxylase, which is involved in the biosynthesis of purine nucleotides. ade2 mutants require an external source of adenine and accumulate precursors of purine nucleotides in the vacuole which give colonies a red color (Zonneveld & Vanderzanden, 1995; Fig. 3B).

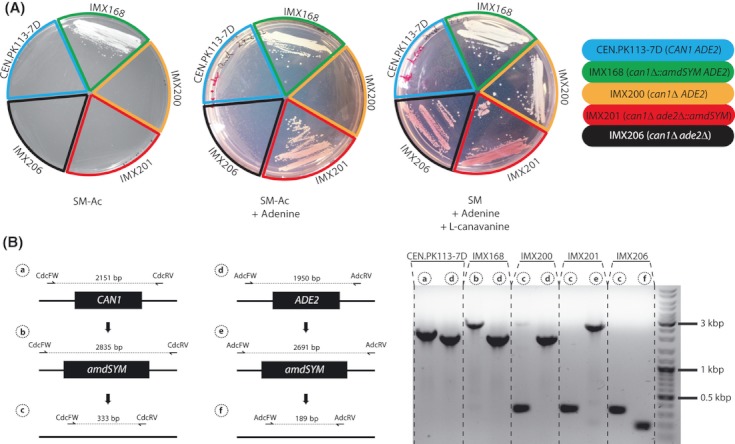

The potential of amdSYM as dominant marker was tested by transforming a deletion cassette to disrupt CAN1 in CEN.PK113-7D. After transformation, cells were grown on synthetic medium (SM) agar plates containing acetamide as sole nitrogen source (SM-Ac, Fig. 4A). Targeted gene deletion was confirmed by the ability of single colonies to grow on SM containing l-canavanine (Fig. 4A) and by PCR (Fig. 4B). The average transformation efficiency was 14 transformants μg−1 of DNA, with 100% of the colonies harboring the correct integration. It is important to note that amdSYM did not yield false positives. Although the transformation efficiency reported here for the deletion of CAN1 may appear low as compared to efficiencies reported for other dominant markers such as KanMX (100 transformants μg−1 DNA) (Guldener et al., 1996), in our experience, the targeted region and the sequence of the deletion cassette affects much more the transformation efficiency than the nature of the marker used. To support this, it has recently been shown that nucleosome density is a critical factor for transformation efficiency, thereby demonstrating that the localization of a deletion cassette has a strong impact on the transformation efficiency (Aslankoohi et al., 2012). With deletions cassettes using amdSYM-based selection but targeted to other loci than CAN1, we observed transformation efficiencies similar to those reported for classical selection markers (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Sequential gene deletions of CAN1 and ADE2 using amdSYM in S. cerevisiae. (A) The strains IMX168, IMX200, and IMX201 and the parental strain CEN.PK113-7D were grown on SM-Ac, SM-Ac supplemented with adenine, and SM supplemented with adenine and l-canavanine. The plates were incubated at 30 °C and were read after 3 days. (B) PCR analysis to confirm correct integration of the gene disruption cassettes and their removal at the CAN1 and ADE2 loci. PCR was carried out on reference CEN.PK113-7D, IMX168, IMX200, and IMX201. All PCRs were performed with the primer pairs CdcFW/CdcRV and AdcFW/AdcRV for CAN1 and ADE2 loci, respectively. In the parental strain, amplification of the CAN1 and ADE2 loci generated fragments of 2151 bp (a) and 1950 bp (d) for CAN1 and ADE2, respectively. PCR on IMX168 DNA generated a fragment of 2835 bp (b) due to the incorporation of amdSYM in the CAN1 locus. A short fragment of 333 bp (c) was obtained for IMX200 as a result of amdSYM excision from the CAN1 locus. Similarly, the disruption of ADE2 using amdSYM led to a large PCR product of 2691 bp in IMX201 (e) while PCR on the ADE2 locus in the marker-free strain IMX206 generated a short fragment of 189 bp (f). The products obtained were then subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis.

The resulting strain IMX168 was subsequently used to evaluate the potential of marker excision aided by the direct repeats created upon integration (Fig. 3B). Under nonselective conditions, that is, growth in complex media (YPD), mitotic recombination between the direct repeats flanking amdSYM may excise the marker. To select for these recombinants, strain IMX168 (can1Δ::amdS) was grown overnight in liquid complex media, transferred to synthetic medium containing fluoroacetamide (SM-Fac), and then plated on SM-Fac. PCR analysis of the growing colonies confirmed correct marker removal (Fig. 4B); the new strain was named IMX200 (can1Δ). Due to the absence of CAN1, IMX200 (can1Δ) was able to grow on media containing l-canavanine. As anticipated, it had lost the ability to grow on media containing acetamide as nitrogen source due to the removal of amdSYM (Fig. 4A). These results confirmed that amdSYM can be successfully used as a selection marker in the prototrophic laboratory strain CEN.PK113-7D and that the marker can be removed to avoid protein burden. An important addition is that the design of the deletion cassette allows for marker removal leaving only endogenous sequences (Fig. 3C).

A strong feature of recyclable markers is that a single marker is sufficient to perform multiple sequential manipulations in the same strain. The potential of amdSYM for serial deletion was tested by deleting a second gene in the marker-free strain IMX200 (can1Δ). After transformation with an amdSYM deletion cassette targeted to ADE2 locus, correct transformants could be easily selected for their ability to grow in the presence of l-canavanine and to use acetamide as nitrogen source and for their auxotrophy for adenine and red pigmentation (Fig. 4A). The strain IMX201 (can1Δ ade2Δ::amdS) was selected using these criteria, and correct integration of the deletion cassette was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 4B). This second deletion demonstrated that amdSYM is a powerful selection marker for serial gene deletion. IMX201 was further engineered to generate the marker-free strain IMX206 (can1Δ ade2Δ) by scarless removal of amdSYM. This was confirmed by sequencing the CAN1 and ADE2 loci in IMX206. Similar to the parental strain CEN.PK113-7D, strain IMX206 (can1Δ ade2Δ) was unable to grow on media containing acetamide as sole nitrogen source but, due to the deletions performed, showed a red pigmentation, was not able to grow in absence of adenine, and was able to grow on media containing l-canavanine (Fig. 4). This marker- and scar-free strain can be subsequently used for additional deletions or other genetic manipulations.

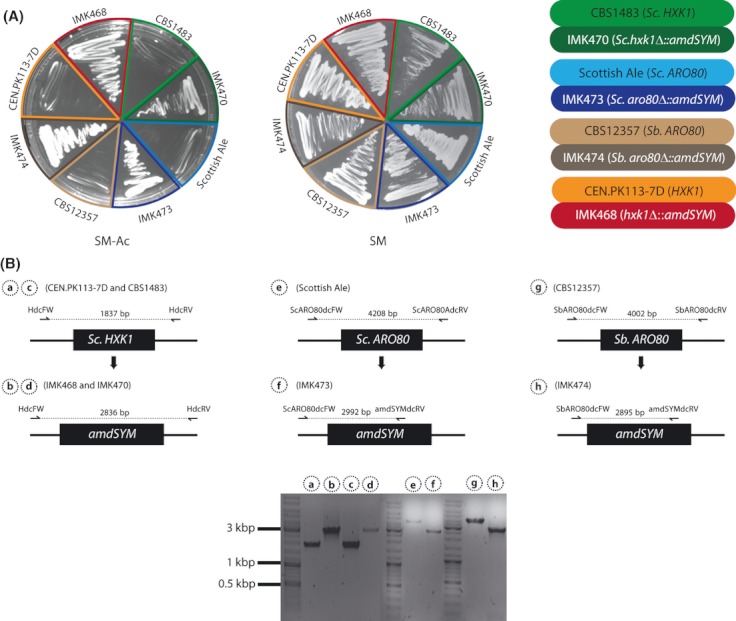

The module amdSYM can be used in a wide range of laboratory, wild, and industrial Saccharomyces strains

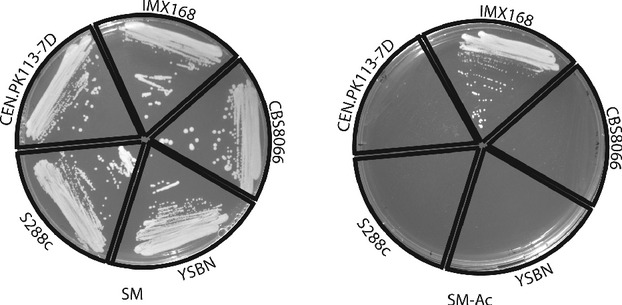

The first condition to use amdSYM as selectable marker is that the parental strain does not have the capability to use acetamide as sole nitrogen source. To verify whether other laboratory strains besides the strains of the CEN.PK lineage could be modified using amdSYM as marker, the ability to grow on media containing acetamide as nitrogen source of three popular laboratory strains, namely CBS8066, YSBN [i.e. a prototrophic BY strain (Canelas et al., 2010)], and S288c (Mortimer & Johnston, 1986), was tested. None of the laboratory strains were able to use acetamide as sole nitrogen source (Fig. 5). To further expand the range of species in which amdSYM could be used, two brewing strains, the S. cerevisiae Scottish Ale strain and the S. pastorianus lager brewing strain CBS1483, and the wild yeast S. eubayanus CBS12357 were tested for their ability to grow on acetamide as sole nitrogen source. Similarly to the laboratory strains, none of these Saccharomyces species grew with acetamide as sole nitrogen source (Fig. 6A). The absence of endogenous acetamidase activity demonstrated that amdSYM could potentially be used as selectable marker in a wide range of laboratory, wild, and industrial Saccharomyces strains.

Fig 5.

Growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae laboratory strains on acetamide as sole nitrogen source. The laboratory strains CEN.PK113-7D, CBS8066, YSBN, S288c, and the modified strain IMX168 (can1Δ::amdSYM) were grown on SM-Ac and SM media and incubated at 30 °C. The plates were read after 3 days. Only the strain harboring the amdSYM module, IMX168, was able to grow when acetamide was used as nitrogen source.

Fig 6.

amdSYM as selectable marker for laboratory, wild, and industrial Saccharomyces strains. (A) The laboratory strain CEN.PK113-7D, the industrial strains CBS1483, Scottish Ale and the wild Saccharomyces eubayanus CBS12357, and the generated strains IMK468, IMK470, IMK473, and IMK474 were grown on SM-Ac and SM media and incubated at 30 °C. The plates were read after 5 days. (B) PCR analysis to confirm correct integration of the gene disruption cassettes was carried out on CEN.PK113-7D, CBS1483, Scottish Ale, CBS12357, IMK468, IMK470, IMK473, and IMK474. Amplification of Sc.HXK1 locus in CEN.PK113-7D and CBS1483 generated fragments of 1837 bp (a, c), bigger fragments, 2836 bp (b, d) were obtained in the strains IMK468 and IMK470 due to the integration of amdSYM. Amplification of the loci Sc.ARO80 in Scottich Ale and Sb.ARO80 in CBS12357 generated fragments of 4208 bp (e) and 4002 bp (g), respectively. Confirmation of the deletion of Sc.ARO80 in IMK473 and Sb.ARO80 in IMK474 by PCR-generated fragments of 2992 bp (f) and 2895 bp (h), respectively. The products obtained were then subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis.

To confirm the universality of amdSYM as selectable marker, genes were deleted using amdSYM in the above-mentioned industrial and wild yeast strains. To compensate for the expected lower efficiency of homologous recombination in these non-cerevisiae species, the deletion cassettes were designed with longer homologous flanking regions of at least 500 bp. The gene HXK1 was deleted in both the laboratory strain CEN.PK113-7D and the S. pastorianus lager brewing strain CBS1483 using cassettes containing amdSYM. Saccharomyces pastorianus is a hybrid species that contains two subgenomes: one that resembles S. cerevisiae genome and another one similar to S. eubayanus (Libkind et al., 2011). In this study, only the S. cerevisiae allele (Sc.HXK1) was deleted. The strains generated were named IMK468 (Sc.hxk1Δ::amdSYM) for the CEN.PK mutant and IMK470 (Sc.hxk1Δ::amdSYM) for the S. pastorianus mutant. Additionally, the S. cerevisiae Scottish Ale brewing strain and the recently described wild yeast S. eubayanus CBS12357 were also genetically modified using amdSYM. Making use of amdSYM as marker cassette the gene Sb.ARO80 was deleted in S. eubayanus resulting in the strain IMK474, and Sc.ARO80 was deleted in the S. cerevisiae Scottish Ale strain, generating the strain IMK473.

IMK468, IMK470, IMK473, and IMK474 all demonstrated the integration of amdSYM in their genomes by their ability to grow on acetamide as sole nitrogen source (Fig. 6A). PCR analysis confirmed the deletion of the targeted genes (Fig. 6B). The growth on acetamide plates was slower for industrial strains as compared to CEN.PK-derived deletion mutants, but increasing the acetamide concentration resulted in faster growth, thereby accelerating the screening process (data not shown). Therefore, the amount of acetamide necessary for amdSYM-based strain construction may be strain-dependent and requires optimization.

Conclusions

When transformed into yeast, A. nidulans amdS conferred the capability to use acetamide as sole nitrogen source. This gain of function allowed the use of amdS as a new dominant marker in S. cerevisiae. In the present work, a new heterologous module, amdSYM, which encompasses the regulatory regions of A. gossypii TEF2 and the A. nidulans gene amdS, was constructed and has been made available for the research community in the widely used plasmid series as pUG-amdSYM. Not only is amdSYM a new dominant marker, but it is also an additional counter-selectable marker in the yeast genetic toolbox. A strong feature of amdSYM is that, contrary to all other counter-selectable markers available, it does not require a specific genetic background for the strain to be selected.

Furthermore, while most marker recycling methods, such as the LoxP-Cre recombinase system, have the disadvantage of leaving scars after each recycling, in the present study, marker removal was scarless (Akada et al., 2006), leaving endogenous sequences after marker excision. In principle, amdSYM can be re-used an unlimited number of times, thus enabling multiple modifications without the protein burden that would cause the overexpression of several heterologous markers.

In conclusion, the new marker module amdSYM is an excellent tool for consecutive genetic modifications in the yeast S. cerevisiae and a good alternative to URA3, MET15, or LYS2 with the additional substantial advantage that it is not limited to specific strain backgrounds or to the cerevisiae species. amdSYM has indeed been successfully used as selection marker to perform deletions in the newly discovered wild species of S. eubayanus and in S. cerevisiae and S. pastorianus brewing strains. Thanks to this later success in deleting genes from the aneuploid and hybrid genome of S. pastorianus, amdSYM is expected to considerably contribute to the functional analysis of genes in strains with complex genome architecture. As the first dominant recyclable marker, amdSYM opens the door to fast and easy genetic manipulation in Saccharomyces laboratory, wild, and industrial strains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Technology Foundation STW (Vidi Grant 10776) and by the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation. J.T.P. and J.-M.D. were also supported by the ‘Platform Green Synthetic Biology’ program (http://www.pgsb.nl/). The S. cerevisiae Scottish Ale strain was a kind gift of Dr. J.M. Geertman (Heineken Supply Chain, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands).

References

- Agha-Mohammadi S, O'Malley M, Etemad A, Wang Z, Xiao X, Lotze MT. Second-generation tetracycline-regulatable promoter: repositioned tet operator elements optimize transactivator synergy while shorter minimal promoter offers tight basal leakiness. J Gene Med. 2004;6:817–828. doi: 10.1002/jgm.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Bussey H. Yeast arginine permease, nucleotide sequence of the CAN1 gene. Curr Genet. 1986;10:587–592. doi: 10.1007/BF00418125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akada R, Kitagawa T, Kaneko S, Toyonaga D, Ito S, Kakihara Y, Hoshida H, Morimura S, Kondo A, Kida K. PCR-mediated seamless gene deletion and marker recycling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2006;23:399–405. doi: 10.1002/yea.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alani E, Cao L, Kleckner N. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics. 1987;116:541–545. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.541.test. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S, Gitler AD, Lindquist S. A suite of Gateway (R) cloning vectors for high-throughput genetic analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2007;24:913–919. doi: 10.1002/yea.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg DC, Botstein D, Beasley EM. Precise gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by double fusion polymerase chain-reaction. Yeast. 1995;11:1275–1280. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apirion D. 2-Way selection of mutants and revertants in respect of acetate utilization and resistance to fluoro-acetate in Aspergillus nidulans. Genet Res. 1965;6:317–329. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslankoohi E, Voordeckers K, Sun H, Sanchez-Rodriguez A, van der Zande E, Marchal K, Verstrepen K. Nucleosomes affect local transformation efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9506–9512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryshnikova A, Costanzo M, Dixon S, Vizeacoumar FJ, Myers CL, Andrews B, Boone C. Synthetic genetic array (SGA) analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:145–179. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin A, Ozierkalogeropoulos O, Denouel A, Lacroute F, Cullin C. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3329–3330. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beri RK, Turner G. Transformation of Penicillium chrysogenum using the Aspergillus nidulans amdS gene as a dominant selective marker. Curr Genet. 1987;11:639–641. doi: 10.1007/BF00393928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy N, Copsey J, Hynes MJ, Davis MA. Yeast proteins can activate expression through regulatory sequences of the amdS gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:223–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00294685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li JC, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canelas AB, Harrison N, Fazio A, et al. Integrated multilaboratory systems biology reveals differences in protein metabolism between two reference yeast strains. Nat Commun. 2010;1:145. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebollero E, Gonzalez R. Comparison of two alternative dominant selectable markers for wine yeast transformation. Appl Environ Microb. 2004;70:7018–7023. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7018-7023.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TH, Abelson J. Identification of a putative amidase gene in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7180. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.7180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattoo BB, Sherman F, Azubalis DA, Fjellstedt TA, Mehnert D, Ogur M. Selection of lys2 mutants of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the utilization of alpha-aminoadipate. Genetics. 1979;93:51–65. doi: 10.1093/genetics/93.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrick CM, Twomey AP, Hynes MJ. The nucleotide sequence of the amdS gene of Aspergillus nidulans and the molecular characterization of 5′ mutations. Gene. 1987;53:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JF, Schiestl RH. Mis-targeting of multiple gene disruption constructs containing hisG. Curr Genet. 2000;38:188–190. doi: 10.1007/s002940000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delneri D, Tomlin GC, Wixon JL, Hutter A, Sefton M, Louis EJ, Oliver SG. Exploring redundancy in the yeast genome: an improved strategy for use of the CreLoxP system. Gene. 2000;252:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpozo L, Abarca D, Claros MG, Jimenez A. Cycloheximide resistance as a yeast cloning marker. Curr Genet. 1991;19:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00309595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijken JP, Bauer J, Brambilla L, et al. An interlaboratory comparison of physiological and genetic properties of four Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000;26:706–714. doi: 10.1016/s0141-0229(00)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drocourt D, Calmels T, Reynes JP, Baron M, Tiraby G. Cassettes of the Streptoalloteichus hindustanus ble gene for transformation of lower and higher eukaryotes to phleomycin resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4009. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B, Sherlock G. Reconstruction of the genome origins and evolution of the hybrid lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus. Genome Res. 2008;18:1610–1623. doi: 10.1101/gr.076075.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entian KD, Kotter P. 25 yeast genetic strain and plasmid collections. In: Stansfield I, Stark J, editors. Methods in Microbiology. Vol. 36. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 629–666. [Google Scholar]

- Ganatra MB, Vainauskas S, Hong JM, et al. A set of aspartyl protease deficient strains for improved expression of heterologous proteins in Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2011;11:168–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatignol A, Baron M, Tiraby G. Phleomycin resistance encoded by the ble gene from transposon Tn5 as a dominant selectable marker in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;207:342–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00331599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, McCusker JH. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:1541–1553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1541::AID-YEA476>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal CV, Broad D, Lloyd D. Bioenergetic consequences of protein overexpression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microb. 1989;30:160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gritz L, Davies J. Plasmid encoded Hygromycin-B resistance the sequence of Hygromycin-B phosphotransferase gene and its expression in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1983;25:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote A, Hiller K, Scheer M, Munch R, Nortemann B, Hempel DC, Jahn D. JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W526–W531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldener U, Heck S, Fiedler T, Beinhauer J, Hegemann JH. A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2519–2524. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.13.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldener U, Heinisch J, Koehler GJ, Voss D, Hegemann JH. A second set of LoxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e23. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield C, Cashmore AM, Meacock PA. An efficient chloramphenicol resistance marker for Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. Gene. 1986;45:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashida-Okado T, Ogawa A, Kato I, Takesako K. Transformation system for prototrophic industrial yeasts using the AUR1 gene as a dominant selection marker. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson RCA, Cox BS, Tubb R. The transformation of brewing yeasts with a plasmid containing the gene for copper resistance. Curr Genet. 1985;9:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hoess RH, Abremski K. Mechanism of strand cleavage and exchange in the Cre-Lox site-specific recombination system. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:351–362. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K, Nielsen J. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a key cell factory platform for future biorefineries. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2671–2690. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0945-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes MJ. Regulatory circuits of the amdS gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1994;65:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00871944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes MJ, Pateman JAJ. Genetic analysis of regulation of amidase synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans. 2. Mutants resistant to fluoroacetamide. Mol Gen Genet. 1970;108:107–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02430517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignea C, Cvetkovic I, Loupassaki S, Kefalas P, Johnson CB, Kampranis SC, Makris AM. Improving yeast strains using recyclable integration cassettes, for the production of plant terpenoids. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JM, Hynes MJ. Transformation of Aspergillus niger by the amdS gene of Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1985;4:475–479. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackova D, Subik J. Use of mutated PDR3 gene as a dominant selectable marker in transformation of prototrophic yeast strains. Folia Microbiol. 1999;44:171–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02816237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlerouault F, Jacobs E. A method for performing precise alterations in the yeast genome using a recyclable selectable marker. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3079–3081. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.15.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libkind D, Hittinger CT, Valerio E, Goncalves C, Dover J, Johnston M, Goncalves P, Sampaio JP. Microbe domestication and the identification of the wild genetic stock of lager-brewing yeast. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14539–14544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105430108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losberger C, Ernst JF. Sequence and transcript analysis of the C. albicans URA3 gene encoding orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase. Curr Genet. 1989;16:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00391471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer RK, Johnston JR. Genealogy of principal strains of the yeast genetic stock center. Genetics. 1986;113:35–43. doi: 10.1093/genetics/113.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 1995;156:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacken V, Achstetter T, Degryse E. Probing the limits of expression levels by varying promoter strength and plasmid copy number in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1996;175:253–260. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki T, Ebihara K, Bannai H, Nakamura Y. Yeast [PSI+] “prions” that are crosstransmissible and susceptible beyond a species barrier through a quasi-prion state. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1121–1130. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp JF, van den Broek M, Datema E, et al. De novo sequencing, assembly and analysis of the genome of the laboratory strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae CEN.PK113-7D, a model for modern industrial biotechnology. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ooyen AJJ, Dekker P, Huang M, Olsthoorn MMA, Jacobs DI, Colussi PA, Taron CH. Heterologous protein production in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:381–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk JT. Auxotrophic yeast strains in fundamental and applied research. Appl Environ Microb. 2002;68:2095–2100. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2095-2100.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S, Ramon D, Perez-Ortin JE. Optimized method to obtain stable food-safe recombinant wine yeast strains. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1689–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Read JD, Colussi PA, Ganatra MB, Taron CH. Acetamide selection of Kluyveromyces lactis cells transformed with an integrative vector leads to high-frequency formation of multicopy strains. Appl Environ Microb. 2007;73:5088–5096. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02253-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro DK, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer B. Functional expression of the CreLoxP site-specific recombination system in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2087–2096. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.6.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorsch C, Kohler T, Boles E. Knockout of the DNA ligase IV homolog gene in the sphingoid base producing yeast Pichia ciferrii significantly increases gene targeting efficiency. Curr Genet. 2009;55:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s00294-009-0252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten G, Swinkels B, Van Gorcom R. Selection marker gene free recombinant strains: A method for obtaining them and the use of these strains. 2000. Pat.no.US6051431.

- Shuster JR, Moyer D, Irvine B. Sequence of the Kluyveromyces lactis URA3 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8573. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Sherman F. Association of methionine requirement with methyl mercury resistant mutants of yeast. Nature. 1974;247:227–229. doi: 10.1038/247227a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, St Onge RP, Mani R, et al. Knocking out multigene redundancies via cycles of sexual assortment and fluorescence selection. Nat Methods. 2011;8:159–164. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels B, Selten G, Bakhuis J, Bovenberg R, Vollebregt A. The use of homologous amdS genes as selectable markers. 1997. Pat.no.WO/9706261.

- Szczebara FM, Chandelier C, Villeret C, et al. Total biosynthesis of hydrocortisone from a simple carbon source in yeast. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:143–149. doi: 10.1038/nbt775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg MA, Steensma HY. Expression cassettes for formaldehyde and fluoroacetate resistance, two dominant markers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:551–559. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199705)13:6<551::AID-YEA113>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers WA, Vandijken JP. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts – A continuous culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast. 1992;8:501–517. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorachek-Warren MK, McCusker JH. DsdA (D-serine deaminase): a new heterologous MX cassette for gene disruption and selection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2004;21:163–171. doi: 10.1002/yea.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A, Brachat A, Alberti-Segui C, Rebischung C, Philippsen P. Heterologous HIS3 marker and GFP reporter modules for PCR-targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1065–1075. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970915)13:11<1065::AID-YEA159>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorke R, Krampe S, Weierstall T, Freidel K, Hollenberg CP, Boles E. Concurrent knock-out of at least 20 transporter genes is required to block uptake of hexoses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1999;464:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Jimenez A. Molecular cloning of a novel allele of SMR1 which determines sulfometuron methyl resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:165–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro CT, Yarden O, Yanofsky C. A dominant selectable marker that is meiotically stable in Neurospora crassa – the amdS gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;236:121–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00279650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YP, Chen XJ, Li YY, Fukuhara H. LEU2 gene homolog in Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast. 1992;8:801–804. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonneveld BJM, Vanderzanden AL. The red ADE mutants of Kluyveromyces lactis and their classification by complementation with cloned ADE1 or ADE2 genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1995;11:823–827. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]