Abstract

Mixed Candida/bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) have been reported to occur in more than 23% of all episodes of candidaemia. However, the clinical implications of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs are not well known. We performed a retrospective case-control study of all consecutive patients with candidaemia over a 5-year period to determine the risk factors for and clinical outcomes of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs (cases) compared with monomicrobial candidaemia (controls). Thirty-seven (29%) out of 126 patients with candidaemia met the criteria for cases. Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the predominant bacteria (23%) in cases. In multivariate analysis, duration of previous hospital stay ≥7 weeks (odds ratio (OR), 2.86; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.09–7.53), prior antibiotic therapy ≥7 days (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.14–0.82) and septic shock at the time of candidaemia (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.14–5.93) were significantly associated with cases. Documented clearance of candidaemia within 3 days after initiation of antifungal therapy was less frequent in cases (63% vs. 84%; p = 0.035). The difference in the rate of treatment failure at 2 weeks was not significant between cases (68%) and controls (62%; p = 0.55). The crude mortality at 6 weeks and survival through 100 days did not differ between the two patient groups (p = 0.56 and p = 0.80, respectively). Mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs showed a lower clearance rate of candidaemia during the early period of antifungal therapy, although the treatment response and survival rate were similar regardless of concurrent bacteraemia. Further studies on the clinical relevance of species-specific Candida-bacterial interactions are needed.

Keywords: Bacteraemia, candidaemia, co-infection, risk factors, treatment outcome

Introduction

Candida species are normal commensals of humans that commonly inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, the female genital tract and the skin, where diverse bacteria are most commonly found. Candida and bacteria directly and indirectly influence each other in many ways and can have important effects on each other’s survival, colonization and pathogenesis [1–3]. Although data on the clinical relevance of interactions between Candida and bacteria are still lacking, several studies have described associations between this genus of fungus and bacteria species in clinical specimens [4–6]. Previous studies have demonstrated both synergistic and antagonistic interactions between Candida and various bacteria species, including Pseudomonas aeroginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumannii [7–11].

With the recent advances in medical technology, Candida species are the most common cause of invasive fungal infections. The occurrence of invasive candidiasis has increased over the past several decades, especially in immunocompromised or critically ill patients, and may contribute to high mortality and morbidity [12,13]. In most cases of candidaemia, the gastrointestinal tract and the skin have been considered the sources of infection [14]. As mentioned above, the extensive distribution of bacterial species can lead to candidaemia with concomitant bacteraemia. Mixed Candida/bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) have been reported to occur in >23% of all episodes of candidaemia [4]. However, the mechanisms of Candida-bacterial interaction in mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs and their clinical importance are not well known. Furthermore, very few studies have compared the clinical characteristics and outcomes of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs and monomicrobial candidaemia [4,15]. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective, case-control study to determine the risk factors for and clinical implications of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs.

Methods

Hospital setting

The retrospective, case-control study was conducted at Korea University Anam Hospital, a 950-bed tertiary care teaching hospital, located in Seoul, South Korea. There are three intensive care units (ICUs) of 56 beds. Blood cultures were processed by the automated system Vitek2 (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea University Anam Hospital. Informed consent was not required by the board because of the retrospective design of this study.

Study design and definitions

We identified all patients aged ≥18 years who had at least one positive blood culture for Candida species and compatible clinical signs or symptoms from July 2006 to June 2011. Among these, mixed Candida/bacterial BSI cases were confirmed by isolation of bacterial species growing concomitantly from a single set or different sets of blood cultures obtained within a 48 h period. We used a standardized definition of contamination [16]. A blood culture was considered to be contaminated if one or more of the following organisms were identified only in one of a series of blood cultures: coagulase-negative staphylococci, Propionibacterium acnes, Micrococcus species, viridians group streptococci, Corynebacterium species or Bacillus species.

Medical records were reviewed to determine demographic data, co-morbidities and other risk factors associated with Candida infection within 30 days before positive blood cultures [17]. Neutropenia was defined as an absolute neutrophil count of <500 cells/mm3. Definitions of septic shock were adapted from the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference Committee [18]. Severity of illness at the onset of candidaemia was assessed using the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score and the Pitt bacteraemia scoring system [19,20]. Source of infection was established by clinical evidence of infection regardless of whether causative organisms were recovered from the affected site. Catheter-related BSIs were defined according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines [21]. Early central venous catheter removal meant removing the central venous catheter within 48 h of drawing the first blood sample that was culture-positive for Candida species.

Blood cultures were usually obtained every 3 days until negative or when clinically indicated. The response to antifungal therapy at 2 weeks was evaluated by the guidelines for assessing treatment responses and defining study outcome in clinical trials of invasive fungal diseases published by the Mycoses Study Group and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer as follows: complete and partial responses were regarded as ‘success’ and stable response, progression of disease and death were regarded as ‘failure’ [22]. Candidaemia-attributable mortality was defined as any of the following: (i) blood cultures positive for Candida species at the time of death; (ii) death before the resolution of signs and symptoms related to candidaemia; or (iii) death at least 14 days after the onset of candidaemia without another explanation. The follow-up duration was 100 days after the first date of culture-positive blood samples for Candida species or until loss to follow-up or death from any cause. The parameters of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs were compared with those of monomicrobial candidaemia.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables represented the median and interquartile range (IQR). The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables, and Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables. Variables with p-values of < 0.20 by univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable model. Multivariate analysis was performed by logistic regression analysis for the risk factors associated with mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs and Cox regression analysis for the predictive factors for mortality. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were used to generate the survival curves and differences between survival curves were assessed by means of the log-rank test. Two-sided p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using spss ver. 15.0 (SPSS Korea, Seoul, Korea).

Results

Patient characteristics

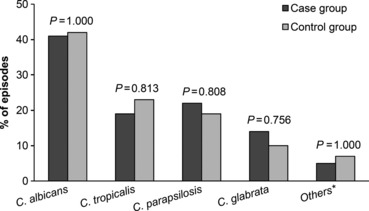

During a 5-year study period, we identified a total of 126 patients who had episodes of significant candidaemia in our institution. The overall incidence of candidaemia was 6.6 cases per 10 000 hospital admissions. The most commonly isolated Candida species was Candida albicans (41% of isolates), followed by Candida tropicalis (21%), Candida parapsilosis (20%) and Candida glabrata (11%). In no case was more than one Candida species isolated. Out of 126 patients, 37 (29%) showed mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs. The characteristics of the patients and the course of therapy in case and control patients are shown in Table 1. The two groups did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics, co-morbidities, risk factors for Candida infection or severity of illness. With regard to the source of candidaemia and antifungal therapy, there was no significant difference. The distribution of Candida species was similar in the two groups (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients with mixed Candida/bacterial bloodstream infections (cases) compared with the patients with monomicrobial candidaemia (controls)

| Characteristics | Cases (n = 37) | Controls (n = 89) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (IQR) | 63 (57–73) | 68 (57–74) | 0.15 |

| Male sex | 19 (51) | 54 (61) | 0.43 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (27) | 24 (27) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (16) | 10 (11) | 0.56 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (8) | 7 (8) | 1.00 |

| Solid tumour | 17 (46) | 43 (48) | 0.85 |

| Haematological disease | 7 (19) | 13 (15) | 0.60 |

| Charlson co-morbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (2–5.5) | 2 (1–6) | 0.78 |

| Prior hospital stay, median days (IQR) | 25 (11–60) | 23 (11–38) | 0.10 |

| Risk factors for Candida infectiona | |||

| ICU residence | 19 (51) | 32 (36) | 0.12 |

| Candida colonization | 7 (19) | 13 (15) | 0.60 |

| Neutropenia | 5 (14) | 14 (16) | 0.79 |

| Chemotherapy | 11 (30) | 24 (27) | 0.83 |

| Corticosteroidb | 12 (32) | 15 (17) | 0.06 |

| Surgery | 9 (24) | 20 (23) | 1.00 |

| Hyperalimentation | 29 (78) | 79 (89) | 0.16 |

| Central venous catheter | 30 (81) | 65 (73) | 0.38 |

| Urinary catheter | 26 (70) | 56 (63) | 0.54 |

| Prior use of antibiotics | 33 (89) | 83 (93) | 0.48 |

| Prior azole exposure | 5 (14) | 11 (12) | 1.00 |

| Severity of illness | |||

| SOFA score, median (IQR) | 7 (3–10) | 6 (2.5–9) | 0.13 |

| Pitt bacteraemia score, median (IQR) | 4 (2–7.5) | 3 (1–6) | 0.14 |

| Source of candidaemia | |||

| Catheter | 10 (27) | 26 (29) | 0.49 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 13 (35) | 41 (46) | |

| Othersc | 3 (8) | 4 (5) | |

| Unknown | 11 (30) | 18 (20) | |

| First-line antifungal agent | |||

| Fluconazole | 18 (49) | 45 (51) | 0.63 |

| Amphotericin B | 9 (24) | 15 (17) | |

| Othersd | 2 (5) | 3 (3) | |

| None | 8 (22) | 26 (29) | |

| Delay in initiation of antifungal therapy, median days (IQR)e | 3 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.53 |

| Total antifungal therapy, median days (IQR) | 22 (7–27) | 14 (7–21) | 0.80 |

Data are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated.

ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Risk factors within 30 days before candidaemia.

A mean minimum dose of 10 mg/day of prednisone equivalent for >14 days.

Genitourinary tract (n = 6) and deep soft tissue (n = 1).

Itraconazole (n = 4) and caspofungin (n = 1).

The time between drawing the first blood samples culture-positive for Candida species and initiation of antifungal therapy.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the distribution of Candida species isolated from cases and controls. *Citrobacter famata (n = 2), Citrobacter guilliermondii (n = 2), Citrobacter ciferrii (n = 1), Citrobacter krusei (n = 1), Citrobacter lusitaniae (n = 1) and Citrobacter sphaerica (n = 1).

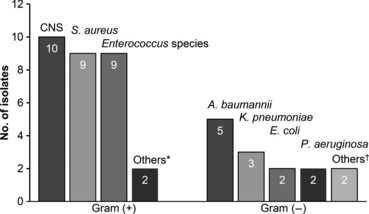

Various bacterial organisms, a total of 44 isolates, were isolated from 37 patients (Fig. 2). Five patients had two and one patient had three bacterial species isolated. Gram-positive organisms accounted for more than 68% (30/44) of all bacterial isolates. Coagulase-negative staphylococci (23%, 10/44) were the most prevalent bacterial pathogen. The central venous catheter (30%, 11/37) and the gastrointestinal tract (30%, 11/37) were the most common sources of bacteraemia, followed by the lower respiratory tract (19%, 7/37), unknown sources (16%, 6/37) and the urinary tract (5%, 2/37). Appropriate antibiotics were administered to all cases except three (one for methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcus and two for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii). Appropriate antibiotic therapy was started on a median of 1 day (IQR, 0–11 days) after the onset of bacteraemia.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of the bacterial species isolated from 37 cases. CNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci. *Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides (n = 1) and Gram-positive bacillus (n = 1). †Citrobacter freundii (n = 1) and Brevundimonas vesicularis (n = 1).

Risk factors for mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs

In univariate analysis, cases tended to have had a previous hospital stay of ≥7 weeks (30% vs. 16%; p = 0.08) and to have received corticosteroids prior to the onset of candidaemia, compared with controls (32% vs. 17%; p = 0.06). Prior antibiotic use for ≥7 days was associated with a lower chance of having mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs (62% vs. 80%; p = 0.04). Cases more commonly manifested as septic shock at the time of candidaemia (51% vs. 32%; p = 0.04). Table 2 shows the results of univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs. After multivariate analysis, previous hospital stay for ≥7 weeks, prior antibiotic use for ≥7 days and the presence of septic shock at the time of candidaemia were significantly associated with mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs.

TABLE 2.

Logistic regression analysis for risk factors associated with mixed Candida/bacterial bloodstream infections

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of previous hospital stay ≥7 weeks | 2.27 (0.92–5.61) | 0.08 | 2.86 (1.09–7.53) | 0.033 |

| ICU residence | 1.88 (0.87–4.09) | 0.11 | – | 0.24 |

| Corticosteroida | 2.37 (0.98–5.73) | 0.06 | – | 0.10 |

| Hyperalimentationa | 0.46 (0.17–1.28) | 0.14 | – | 0.16 |

| Duration of prior antibiotic therapy ≥7 daysa | 0.42 (0.18–0.97) | 0.04 | 0.33 (0.14–0.82) | 0.016 |

| Septic shock | 2.30 (1.05–5.04) | 0.04 | 2.60 (1.14–5.93) | 0.024 |

| SOFA score ≥10 | 1.87 (0.81–4.32) | 0.14 | – | 0.42 |

| Pitt bacteraemia score ≥8 | 2.06 (0.79–5.42) | 0.14 | – | 0.41 |

ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Risk factors within 30 days before candidaemia.

Clinical outcome of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs

The clinical outcomes of cases and controls are shown in Table 3. Within 3 days after initiation of antifungal therapy, documented clearance of candidaemia was significantly infrequent in cases (p = 0.035; Table 3). After adjustment for the first-line antifungal agent, ≥48 h delay in initiation of antifungal therapy and early removal of central venous catheter by multivariate analysis, mixed Candida/bacterial BSI was only a significant factor associated with clearance of candidaemia at day 3 (OR, 0.26; 98% CI, 0.08–0.84; p = 0.024). For the treatment response at 2 weeks, 25 of 37 (68%) cases and 55 of 89 (62%) controls had a treatment failure (p = 0.55). Of the reasons for treatment failure, microbiological failure was observed for 14% of cases and 6% of controls (p = 0.16). In subgroup analysis according to Candida and bacterial species, there were no significant differences in the documented clearance of candidaemia within 3 days or treatment response at 2 weeks (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of clinical outcomes between patients with mixed Candida/bacterial bloodstream infections (cases) and those with monomicrobial candidaemia (controls)

| Variables | Cases (n = 37) | Controls (n = 89) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Documented clearance of candidaemia within 3 days after initiation of antifungal therapya | 19/30 (63) | 48/57 (84) | 0.035 |

| Treatment failure at 2 weeks | 25 (68) | 55 (62) | 0.55 |

| Clinical failureb | 5 (14) | 13 (15) | 1.00 |

| Microbiological failurec | 5 (14) | 5 (6) | 0.16 |

| Death | 15 (41) | 37 (42) | 1.00 |

| Mortality at 6 weeks | |||

| Crude | 24 (65) | 50 (56) | 0.43 |

| Candidaemia-attributable | 16 (43) | 37 (42) | 1.00 |

Data are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated.

Data are event/evaluable no. (%) of patients.

Worsening or no improvement of attributable symptoms or signs of candidaemia.

Persistent isolation of Candida species from blood specimens at 2 weeks.

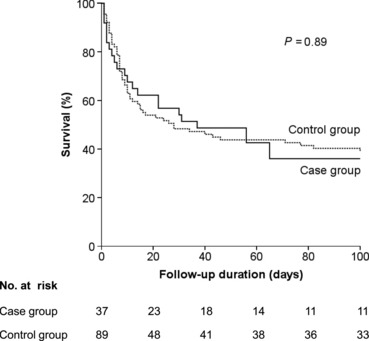

Overall mortality at 6 weeks was 59% (74/126) of all candidaemic patients. Thirty-four (27%) patients did not receive any antifungal therapy; of these, 28 (82%) died at week 6. Differences between cases and controls were not significant in the crude and candidaemia-attributable mortality at 6 weeks (p = 0.43 and p = 1.00, respectively; Table 3). In univariate analysis, mixed Candida/bacterial BSI was not predictive of crude mortality at 6 weeks (p = 0.72). Predictive factors of the 6-week mortality are shown in Table 4. After multivariate analysis, a Charlson co-morbidity index ≥4, surgery, SOFA score ≥10, Pitt bacteraemia score ≥8, delay in initiation of antifungal therapy >72 h and persistent candidaemia at the last blood culture remained independent predictors for crude mortality at 6 weeks. Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival are shown in Fig. 3. The median time to death was 45 days in cases and 40 days in controls (p = 0.89).

TABLE 4.

Predictors of the 6-week mortality in all candidaemic patients

| Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Candida/bacterial BSI | 1.09 (0.67–1.78) | 0.72 | – | ND |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 0.76 (0.42–1.39) | 0.37 | – | ND |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 1.67 (0.86–3.25) | 0.13 | – | 0.15 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.03 (1.11–3.72) | 0.021 | – | 0.96 |

| Charlson co-morbidity index ≥4 | 1.79 (1.13–2.85) | 0.014 | 1.91 (1.17–3.13) | 0.01 |

| Risk factors for Candida infectiona | ||||

| ICU residence | 1.77 (1.12–2.80) | 0.015 | – | 0.36 |

| Neutropenia | 1.46 (0.82–2.62) | 0.20 | – | 0.08 |

| Chemotherapy | 1.56 (0.95–2.54) | 0.08 | – | 0.15 |

| Corticosteroids | 1.59 (0.94–2.68) | 0.09 | – | 0.27 |

| Surgery | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | 0.02 | 0.34 (0.17–0.65) | 0.001 |

| Hyperalimentation | 1.72 (0.83–3.60) | 0.15 | - | 0.31 |

| Severity of illness | ||||

| SOFA score ≥10 | 3.78 (2.33–6.12) | <0.001 | 3.00 (1.73–5.18) | <0.001 |

| Pitt bacteraemia score ≥8 | 4.83 (2.80–8.33) | <0.001 | 6.98 (3.32–14.70) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.90 (1.19–3.02) | 0.007 | – | 0.76 |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 1.90 (1.02–3.54) | 0.04 | – | 0.07 |

| Delay in initiation of antifungal therapy >72 h | 1.87 (1.16–3.00) | 0.01 | 2.03 (1.23–3.35) | 0.006 |

| Early central venous catheter removal | 0.68 (0.41–1.13) | 0.13 | – | 0.99 |

| Persistent candidaemia at the last blood culture | 5.87 (3.62–9.52) | <0.001 | 7.60 (4.36–13.25) | <0.001 |

BSI, bloodstream infection; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Risk factors within 30 days prior to candidaemia.

FIG. 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival in patients with mixed Candida/bacterial bloodstream infection and monomicrobial candidaemia.

Discussion

In this study, a significant portion of candidaemia episodes occurred concurrently with bacteraemia. Compared with monomicrobial candidaemia, mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs were associated with a prolonged length of previous hospital stay (≥7 weeks) and septic shock at the time of candidaemia. Prior receipt of antibiotic agents for ≥7 days was related to monomicrobial candidaemia rather than mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs. We found that documented clearance of candidaemia during the early period of antifungal therapy was deferred in patients with concurrent bacteraemia. However, treatment responses at 2 and 6 weeks and survival through 100 days were not significantly different between mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs and monomicrobial candidaemia.

Mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs have been commented in several articles on candidaemia, the results of which have suggested that the incidence of concurrent bacteraemia accounts for 23% of all episodes of candidaemia [4,23]. Thorn et al. [24] reported that 39% of the post-mortem blood cultures with Candida species were polymicrobial. We observed a similar incidence in previous studies. However, the concept of ‘polymicrobial BSI’ or ‘concomitant BSI’ was not properly identified in most previous articles and an official definition has still not been established. The following definition has mainly been used: the isolation of bacterial species synchronously with Candida species or within 48 h of the time of candidaemia. Previous studies have reported the incidence of concurrent bacteraemia to be 7–27%. Abi-Said et al. [25] showed that concomitant bacterial infection defined as isolation of bacteria 1 week prior to or after the time of candidaemia occurred in 57% of patients. In this study, we used the term ‘mixed Candida/bacterial BSI’ to describe the isolation of bacterial species within 48 h of the time of candidaemia to avoid confusion with previous studies. We chose this definition because concomitant bacteraemia may obscure the detection of fungaemia using standard blood culture techniques by suppression of fungal growth [9,10,26]. The inclusion of only synchronous candidaemia and bacteraemia could cause the underestimation of the incidence of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs.

We found that clearance of candidaemia within 3 days after the start of antifungal therapy was significantly infrequent in mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs, compared with monomicrobial candidaemia. This result might be explained by the following mechanisms: the synergistic relationship between Candida and bacteria species enhances the viability of Candida [27,28], and/or fungal growth is increased by antibacterial treatment for co-infected bacteria with an antagonistic effect on Candida species [10,29]. However, the clinical significance of synergism between Candida and bacteria species has not been proven, and quantitative blood culture was not performed in this study. Further in vitro and in vivo investigations are needed to test this hypothesis.

It is not yet clear whether mixed-species infections have different clinical outcomes than single-species infections. Several studies have reported significant implications of Candida-bacterial interactions in animal models and various clinical settings, including biofilms on implanted medical devices, peritonitis and ventilator-associated pneumonia [6,8,30,31]. As far as we know, only one study has compared clinical outcomes in BSIs by mixed Candida-bacteria species and Candida species alone. Dyess et al. [15] reported a poorer clinical outcome in patients with synchronous candidaemia and bacteraemia (39% survival) than in patients with only candidaemia (67% survival; p < 0.05). However, they did not present the demographic characteristics, underlying disease and severity of illness in each patient group. Unlike their result, our study showed no difference in clinical outcome between mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs and monomicrobial candidaemia. Concomitant bacteraemia was also not a predictive factor of the 6-week mortality. Mortality at 6 weeks was associated with the Charlson co-morbidity index, SOFA score, Pitt bacteraemia score, recent surgery, delayed start of antifungal therapy and persistent candidaemia. These findings suggest that chronic co-morbid conditions and severity of illness at the onset of candidaemia are the key factors of clinical outcome of candidaemic patients.

This study has several limitations. Because we performed a retrospective analysis with single-centre data, the distribution of the causative pathogens (both Candida and bacteria species) in our institution could have had an impact on the results. Also, a relatively small number of cases caused by each bacterial species was included and we did not analyse the clinical influence of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs according to the bacterial species. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the risk factors for and clinical outcomes of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs compared with monomicrobial candidaemia. Our results suggest that empirical antibacterial and antifungal therapy should be properly considered on the basis of local microbiological epidemiology and susceptibility profiles in cases with risk factors for mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs. Although mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs are not predictive for a poor prognosis with appropriate antimicrobial therapy, more aggressive policies to clear Candida species from blood might be required in the early period of antimicrobial therapy to minimize the possibility of metastatic complications.

In our study, mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs accounted for a considerable part of candidaemia. We found several risk factors for and clinical implications of mixed Candida/bacterial BSIs. The interactions between Candida and bacteria species are highly complex and their clinical impact could be influenced by host factors, microbial pathogen and antimicrobial therapy. To understand the mechanisms of Candida-bacterial interactions in the bloodstream and exploit it for therapeutic strategies, further studies using in vitro or animal model systems as well as large-scale, multicentre clinical data are needed.

Acknowledgments

Part of this research was presented at the 22nd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), London, United Kingdom, 2012 (P 784).

Transparency Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authorship/Contribution

S. H. Kim and J. W. Sohn designed the study; S. H. Kim and Y. K. Yoon collected and analysed the data; J. W. Sohn and M. J. Kim interpreted the data; S. H. Kim and J. W. Sohn coordinated writing and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Peleg AY, Hogan DA, Mylonakis E. Medically important bacterial-fungal interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:340–349. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirtliff ME, Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA. Cross-kingdom interactions: Candida albicans and bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;299:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wargo MJ, Hogan DA. Fungal-bacterial interactions: a mixed bag of mingling microbes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klotz SA, Chasin BS, Powell B, Gaur NK, Lipke PN. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections involving Candida species: analysis of patients and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermann C, Hermann J, Munzel U, Ruchel R. Bacterial flora accompanying Candida yeasts in clinical specimens. Mycoses. 1999;42:619–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.1999.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Tafflet M, et al. Candida colonization of the respiratory tract and subsequent pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129:110–117. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akagawa G, Abe S, Yamaguchi H. Mortality of Candida albicans-infected mice is facilitated by superinfection of Escherichia coli or administration of its lipopolysaccharide. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1539–1544. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson E. Effect of strain of Staphylococcus aureus on synergism with Candida albicans resulting in mouse mortality and morbidity. Infect Immun. 1983;42:285–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.285-292.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grillot R, Portmann-Coffin V, Ambroise-Thomas P. Growth inhibition of pathogenic yeasts by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro: clinical implications in blood cultures. Mycoses. 1994;37:343–347. doi: 10.1111/myc.1994.37.9-10.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaleli I, Cevahir N, Demir M, Yildirim U, Sahin R. Anticandidal activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from clinical specimens. Mycoses. 2007;50:74–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peleg AY, Tampakakis E, Fuchs BB, Eliopoulos GM, Moellering RC, Jr, Mylonakis E. Prokaryote-eukaryote interactions identified by using Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14585–14590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805048105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tortorano AM, Peman J, Bernhardt H, et al. Epidemiology of candidaemia in Europe: results of 28-month European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) hospital-based surveillance study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:317–322. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassetti M, Taramasso L, Nicco E, Molinari MP, Mussap M, Viscoli C. Epidemiology, species distribution, antifungal susceptibility and outcome of nosocomial candidemia in a tertiary care hospital in italy. PLoS one. 2011;6:e24198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nucci M, Anaissie E. Revisiting the source of candidemia: skin or gut? Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1959–1967. doi: 10.1086/323759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyess DL, Garrison RN, Fry DE. Candida sepsis. Implications of polymicrobial blood-borne infection. Arch Surg. 1985;120:345–348. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390270083014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bekeris LG, Tworek JA, Walsh MK, Valenstein PN. Trends in blood culture contamination: a College of American Pathologists Q-tracks study of 356 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1222–1225. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1222-TIBCCA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nace HL, Horn D, Neofytos D. Epidemiology and outcome of multiple-species candidemia at a tertiary care center between 2004 and 2007. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee JY, Kwon KT, Ki HK, et al. Scoring systems for prediction of mortality in patients with intensive care unit-acquired sepsis: a comparison of the Pitt bacteremia score and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scoring systems. Shock. 2009;31:146–150. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318182f98f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45. doi: 10.1086/599376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segal BH, Herbrecht R, Stevens DA, et al. Defining responses to therapy and study outcomes in clinical trials of invasive fungal diseases: Mycoses Study Group and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus criteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:674–683. doi: 10.1086/590566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulimood S, Ganesan L, Alangaden G, Chandrasekar P. Polymicrobial candidemia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;44:353–357. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00460-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorn JL, Gilchrist KB, Sobonya RE, Gaur NK, Lipke PN, Klotz SA. Postmortem candidaemia: marker of disseminated disease. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:337–340. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.070607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abi-Said D, Anaissie E, Uzun O, Raad I, Pinzcowski H, Vartivarian S. The epidemiology of hematogenous candidiasis caused by different Candida species. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1122–1128. doi: 10.1086/513663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hockey LJ, Fujita NK, Gibson TR, Rotrosen D, Montgomerie JZ, Edwards JE., Jr Detection of fungemia obscured by concomitant bacteremia: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:1080–1085. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.6.1080-1085.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adam B, Baillie GS, Douglas LJ. Mixed species biofilms of Candida albicans and Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:344–349. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-4-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson E. Enhancement by Candida albicans of Staphylococcus aureusSerratia marcescens, and Streptococcus faecalis in the establishment of infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1983;39:193–197. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.193-197.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandara HM, Yau JY, Watt RM, Jin LJ, Samaranayake LP. Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits in-vitro Candida biofilm development. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nseir S, Jozefowicz E, Cavestri B, et al. Impact of antifungal treatment on Candida-Pseudomonas interaction: a preliminary retrospective case-control study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0422-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramage G, Saville SP, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm formation by farnesol, a quorum-sensing molecule. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5459–5463. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5459-5463.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]