Abstract

In this issue, Lee et al. (2012) demonstrate that the degradation of RORα is regulated by the EZH2–DCAF1/DDB1/CUL4–proteasome axis, thus, identifying protein methylation as a post-translational modification that can orchestrate protein destruction through a motif termed the “methyl-degron.”

Protein methylation typically takes place on arginine or lysine residues, and is often involved in fine-tuning protein function. Arginine methyltransferases (RMTs) and lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) are responsible for depositing methyl group(s) on protein substrates. Importantly, both lysine and arginine residues can be modified to different degrees and each methylated state may have a different functional consequence. Key in translating these methyl-marks into a biological effect is the existence of a large number of “readers” or effector molecules for the different methylated motifs. These effector molecules harbor unique protein folds that bind methyl-motifs, including Chromo, Tudor, MBT, BAH and PWWP domains (Yun et al., 2011). With regard to histone tail methylation, effector molecule binding generally regulates the accessibility of chromatin for transcription and DNA repair. The biological roles of non-histone lysine methylation are not as well understood. Sung Hee Baek and colleagues shed light on this topic by identifying RORα, an orphan nuclear receptor, as an EZH2 substrate, and introduce an intriguing new discovery of EZH2-mediated protein marking as a signal for destruction (Lee et al., 2012).

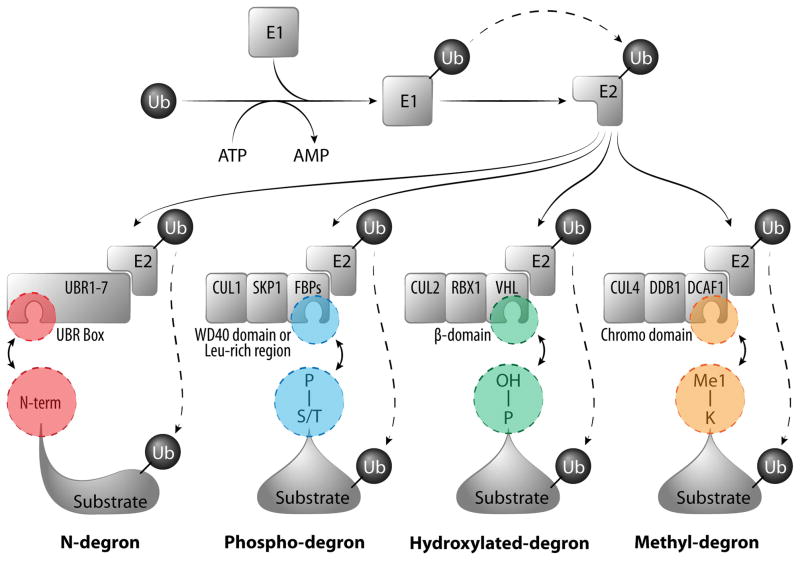

In the eukaryotic cells, most short-lived proteins, including transcriptional factors, are targeted for degradation through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. A cascade of ubiquitin activation (E1), conjugation (E2), and ligation (E3) enzymes catalyze the addition of mono- and polyubiquitin to the substrates. The E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases provide specificity for this ubiquitin-tagging system by physically recognizing the substrate proteins that are destined for proteasome-mediated destruction. In the human genome, there are only two E1 and fewer than 40 E2 enzymes, but over 600 different E3s which provide specificity for this system (Ravid and Hochstrasser, 2008). These E3 substrate-binding adaptors contain conserved surfaces or domains that selectively interact with linear motifs on their dedicated substrates. These motifs, which are often targets of posttranslational modification, have been referred to as “degrons” (Varshavsky, 1991). By definition, a degron is an element that is necessary and sufficient for recognition by the proteolytic apparatus, and thus, if such a degron is attached to a long-lived protein, it will reduce the lifespan of that protein. A number of degrons conform to these criteria, including N-degrons (particular N-terminal residues decrease protein half-life), phospho-degrons (motifs which are serine/threonine phosphorylated) and an hydroxylated-degron (a motif that is prolyl-hydroxylated) (Ravid and Hochstrasser, 2008) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Degrons that facilitate targeting of the Ub-proteasome system.

Short-lived proteins in eukaryotes are recognized and degraded by Ub-proteasome system, a process that is coordinated by consecutive enzymatic steps (ubiquitin activation by E1; conjugation by E2; and ligation by E3) and culminates in the transfer of ubiquitin (Ub) to a lysine residue within the substrate. Ub can be added either individually or in chains. The specificity of this system is achieved by substrate recognition modules that form part of E3 complexes (the family of HECT E3s are not included here). The UBR Box in UBR proteins recognize specific N-terminal residues (N-degron); F-Box proteins (FBPs) form part of the CUL1/SKP1 complex and harbor either WD40 domains or Leucine-rich regions that recognize phosphorylated serine or threonine residues (Phospho-degron); the β-domain of VHL protein in CUL2/RBX1 complex recognizes proline residues that are hydroxylated (Hydroxylated-degron); and the Chromo domain of DCAF1 in CUL4/DDB1 complex recognizes mono-methylated lysine motifs (Methyl-degron).

Lee et al. start their story with an in silico homology search for non-histone substrates of EZH2, using the amino acid sequence “R-K-S,” which surrounds the well-characterized EZH2 methylation site at H3K27. The authors subsequently focused on the transcriptional factor, RORα, which harbors the “R-K-S” sequence at lysine 38 (K38). Site-directed mutagenesis of K38 disrupts RORα methylation as detected by a pan-methyllysine antibody. Furthermore, in vitro methylation by EZH2 of a RORα peptide that harbors the K38 site, followed by mass spectrometry analysis, reveals that this site is mono-methylated. The authors also generated RORα methyl-specific antibodies (mono-, di- and tri-specific) to demonstrate that the mono-methylated K38 modification indeed exists in cells.

RORα is known to be a short-lived protein and its’ degradation is mediated by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. However, very little is known about the signals that regulate RORα protein stability. EZH2 knockout MEF cells show dramatic stabilization of the RORα protein, suggesting methylation of RORα by EZH2 is a key event in this process. Overexpression of wild-type EZH2, but not the enzymatic mutant form, dramatically increases RORα ubiquitination, further indicating that RORα methylation status is correlated with its ubiquitination level. To gain an understanding of how ROα is targeted for degradation, the authors identified the components of the CUL4 E3 ligase complex (DDB1 and DCAF1) as proteins that are tightly associated with the tagged form of RORα. Importantly, the CUL4 E3 complex has been implicated in the regulation of histone methylation (Higa et al., 2006). Lee et al. identify a putative Chromo domain in DCAF1 and demonstrate that it recognizes the RORαK38me1 motif. Furthermore, computational modeling reveals that the aromatic cage of the DCAF1 Chromo domain can only accommodate a mono-methyl group (not H3K27me3), due to its small pocket size. DCAF1 thus harbors a putative Chromo domain that can “read” the methyl-degron generated by EZH2. When the methyl-degron of RORα is transferred to histone H3, the histone becomes heavily ubiquitinated, thus complying with a key rule for degron classification.

EZH2 levels are upregulated in a wide range of cancer types, and this enzyme is an attractive target for anticancer treatment (Chang and Hung, 2012). RORα has a number of reported tumor suppressive roles and some of the oncogenic properties of EZH2 may be explained by its ability, when overexpressed, to facilitate a shortening of the RORα half-life. Indeed, Lee et al. show that EZH2 expression is inversely correlated with RORα expression in breast cancer samples.

It is likely that the RORα methyl-degron that is targeted by the EZH2–DCAF1/DDB1/CUL4–proteasome axis is just the tip of the iceberg. To date, only one other non-histone substrate has been identified for EZH2, namely GATA4, which is mono-methylated at K299 (He et al., 2012). It will also be very interesting to determine whether GATA4 is targeted for degradation by this pathway. Furthermore, there are a number of other KMTs that deposit mono-methyl marks and could generate docking sites for the putative Chromo domain of DCAF1. Indeed, the findings reported by the Baek laboratory were foreshadowed by reports that another KMT, KMT7 (also called Set9, Set7/9 or Setd7), is involved in regulating protein stability (Yang et al., 2009). KMT7 is a mono-methyltransferase that not only deposits the H3K4me1 mark, but also methylates a host of non-histone proteins. The methylation of two of these proteins, NFκB and DNMT1, results in de-stabilization, possibly because they harbor methyl-degrons.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chang CJ, Hung MC. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:243–247. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A, Shen X, Ma Q, Cao J, von Gise A, Zhou P, Wang G, Marquez VE, Orkin SH, Pu WT. Genes Dev. 2012;26:37–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.173930.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa LA, Wu M, Ye T, Kobayashi R, Sun H, Zhang H. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1277–1283. doi: 10.1038/ncb1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Lee JS, Kim H, Kim K, Park H, Kim J-Y, Lee SH, Kim IS, Kim J, Lee M, et al. Molecular Cell. 2012:xxx–xxx. [Google Scholar]

- Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–690. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshavsky A. Cell. 1991;64:13–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90202-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XD, Lamb A, Chen LF. Epigenetics. 2009;4:429–433. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.7.9787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun M, Wu J, Workman JL, Li B. Cell Res. 2011;21:564–578. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]