Abstract

Holocarboxylase synthetase (HLCS) is part of a multiprotein gene repression complex and catalyzes the covalent binding of biotin to lysines (K) in histones H3 and H4, thereby creating rare gene repression marks such as K16-biotinylated histone H4 (H4K16bio). We tested the hypothesis that H4K16bio contributes toward nucleosome condensation and gene repression by HLCS. We used recombinant histone H4 in which K16 was mutated to a cysteine (H4K16C) for subsequent chemical biotinylation of the sulfhydryl group to create H4K16Cbio. Nucleosomes were assembled by using H4K16Cbio and the ‘Widom 601’ nucleosomal DNA position sequence; biotin-free histone H4 and H4K16C were used as controls. Nucleosomal compaction was analyzed using atomic force microscopy (AFM). The length of DNA per nucleosome was ~30% greater in H4K16Cbio-containing histone octamers (61.14±10.92 nm) compared with native H4 (46.89±12.6 nm) and H4K16C (47.26±10.32 nm), suggesting biotin-dependent chromatin condensation (P <0.001). Likewise, the number of DNA turns around histone core octamers was ~17.2% greater in in H4K16Cbio-containing octamers (1.78±0.16) compared with native H4 (1.52±0.21) and H4K16C (1.52±0.17), judged by the rotation angle (P <0.001; N=150). We conclude that biotinylation of K16 in histone H4 contributes toward chromatin condensation.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, biotin, histone H4, lysine-16, nucleosomes, ‘Widom 601’ nucleosomal DNA position sequence

1. INTRODUCTION

Nucleosomal core particles (NCP) are composed of a histone H3/H3/H4/H4 tetramer and two histone H2A/H2B dimers, around which ~147 bp of DNA is wrapped in ~1.7 turns [1, 2]. Nucleosomal (chromatin) condensation hinders the access of proteins such as RNA polymerases to DNA. A number of strategies have evolved to regulate access to nucleosomal DNA, including posttranslational modification of histones, the incorporation of histone variants, and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling [3]. Histones are modified post-translationally by covalent attachment of a variety of predominantly small molecules [4–8]. These modifications provide an important regulatory mechanism for regulating gene expression, replication, and DNA repair [9, 10]. For example, acetylation of lysines (K) 5, 8, 12, and 16 in histone H4 is associated with transcriptionally active chromatin, whereas histone deacetylation is associated with inactive chromatin [11, 12]. Acetylation of K16 in histone H4 (H4K16ac) is a frequent epigenetic mark with major implications in chromatin structure [13–15].

Histones H3 and H4 are also modified by covalent binding of biotin to lysine residues. Biotinylated histones have been detected using radiotracers, streptavidin, anti-biotin, and biotinylation site-specific antibodies as probes [5, 7, 8, 16–18]. Biotinylation sites include K12 and K16 in histone H4 (H4K12bio and H4K16bio) [7, 8, 17, 18].

Biotinylation of histones is catalyzed by holocarboxylase synthetase (HLCS) [19, 20]. HLCS knockdown produces strong phenotypes including heat stress susceptibility and short life span in Drosophila melanogaster [21], and de-repression of long terminal repeats in humans, mice, and flies [22]. The abundance of biotinylation marks in the human epigenome depends on dietary biotin in humans and fruit fly [22, 23] and on the concentration of biotin in cell culture media [17, 18, 22, 24]. Histone biotinylation marks are enriched in repressed loci [17, 18, 22, 24, 25], where they co-localize with the well-established H3K9me gene repression mark [12]. The putative role of biotin in gene repression has been corroborated by atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies of H4K12bio, suggesting that biotinylation of histones causes condensation of nucleosomes [26].

Biotinylation of histones is a rare event and only <0.001% of histones H3 and H4 are biotinylated [5, 8, 27]. The rarity of biotinylation marks raises concern as to how this modification can elicit major biological effects and precipitate severe phenotypes. HLCS catalyzes the binding of biotin to both histones and carboxylases [28], rendering it difficult to assign phenotypes solely and unambiguously to changes in histone biotinylation. Recent studies in transgenic Drosophila suggest for the first time that phenotypes are different for HLCS knockdown flies (decreased heat stress survival, short life span) compared with carboxylase mutants (increased stress survival), thereby implying histone biotinylation in gene regulation by mechanisms distinct from those due to changes in carboxylase biotinylation [21, 29].

Due to remaining uncertainties regarding histone biotinylation we integrated previous findings by us and others into the following novel model. We propose that the roles of biotin and HLCS in gene regulation are mediated primarily by HLCS-dependent assembly of a multiprotein gene repression complex in human chromatin [8], and that biotinylation marks are markers for HLCS docking sites in chromatin in addition to contributing toward chromatin condensation [26].

Given the pre-eminent role of K16 marks in altering chromatin condensation states [13, 14] we hypothesized that the newly discovered H4K16bio mark [18] has a greater effect on mediating chromatin condensation than that described before for H4K12bio [26]. Here we quantified H4K16bio-dependent chromatin condensation by AFM [26, 30–32].

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Principle of atomic force microscopy (AFM)

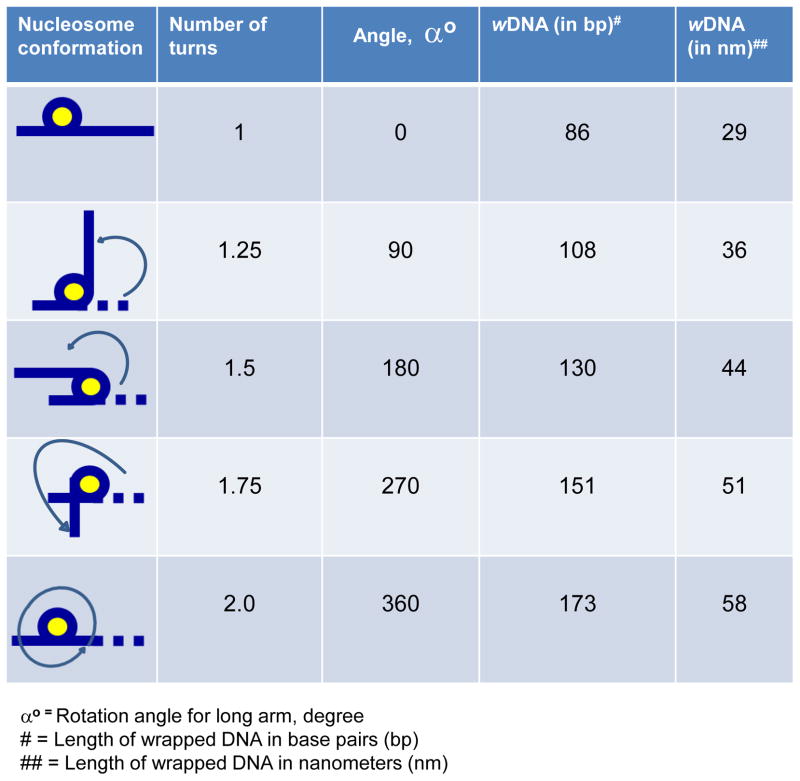

In this study, we used the ‘Widom 601’ nucleosomal position DNA sequence for nucleosomal assembly. Widom 601 spans 147 bp of DNA that has high affinity for histone octamers, flanked by two arms of 79 bp and 127 bp that extend from the nucleosomal surface [30] (Supporting Information Fig. S1A). The distinct length of these arms allows quantifying the length of DNA in a nucleosome and assessing the number of DNA turns around a histone octamer (Fig. 1) [33].

Figure 1. DNA supercoiling in nucleosomal core particles.

Adopted and modified from [30].

2.2 Nucleosomal DNA

Plasmid pGEM3Z/601 contains the nucleosome positioning sequence denoted Widom 601 and was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge) [34]. The 353-bp insert was amplified by PCR (34 cycles of 94°C/30 s, 54°C/30 s, 72°C/30 s) using forward primer 5′-GGCCAGTGAATTGTAATACG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGGGATCCTAATGACCAAGG-3′. The amplicon size and integrity were confirmed using 1% agarose gels, The PCR product was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, and the DNA was dissolved in water. The DNA was ran on a 1% agarose gel and extracted using a gel extraction kit (Epoch Life Science). Purified Widom 601 DNA was stored at −20°C.

2.3 Expression and purification of histones

Histone expression, purification and histone octamers refolding were performed as described previously [35] with some minor modifications. Briefly, full-length Xenopus laevis histones H2A (pET3a), H2B (pET3a), H3 (pET3d) (gift by Dr. K. Luger, Colorado State University) and H4 (pET3a) were individually transformed and expressed in E. coli [BL21 (DE3) pLysS; Invitrogen]. Histones were purified by gel filtration using a Sephacryl S-200 column and an ÄKTA-FPLC (GE Healthcare) system. Purity and integrity was confirmed using SDS-PAGE precast gels (Invitrogen). Histone fractions were dialyzed against three changes of water and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol at 4°C. Histones were lyophilized and stored at −20°C.

2.4 Generation of H4K16C by site directed mutagenesis

H4K16C was created using the GenetailorTM site directed mutagenesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using histone H4 from X. laevis in a pET3a vector system was used as starting material. For the PCR-based mutagenesis reaction, we used forward (sense) primer 5′-TCTGGGTAAAGGTGGTGCTTGTCGTCACCGTAAA-3′ and reverse (antisense) primer 5′-AGCACCACCTTTACCCAGACCTTTACCACCTT-3′. DH5α-T1 R competent cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with the mutant plasmid and the mutation was verified by sequencing.

2.5 Expression and purification of histone H4K16C

BL-21 competent cells were transformed with the pET3a plasmid coding for H4K16C and single clone was expanded overnight in 5 ml 2X-YT media at 37oC gentle agitation. The culture was further expanded by inoculating 100 ml 2X- YT media (containing 100μg/ml ampicillin and 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol) with 1 ml of the stock culture and incubation at 37oC for 4 h, and a final expansion step in 2 l of media. Protein expression was induced with 0.4 mM IPTG at 37°C for 2 h and cell pellet was collected and resuspended in wash buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercapthoethanol, pH 7.5) at −80°C overnight. Next day inclusion bodies were prepared after lysis and sonication and finally centrifugation at 12,000 g at RT for 30 min. Inclusion bodies were soaked in 1 ml DMSO at RT for 30 min, resuspended in 10 ml of unfolding buffer (6 M guanidine hydrochloride) at RT for 1 h, and centrifuged at RT and 12,000 g for 30 min. H4K16C was purified using a Sephacryl S-200 column dialyzed, and lyophilized.

Previous studies suggest that microbial BirA in E. coli has enzymatic activity to biotinylate recombinant histones, albeit at low levels [19]. To avoid artifacts caused by biotinylation of lysine residues other than K16 in subsequent assays, we removed the biotinylated fraction of recombinant H4K16C using avidin agarose resin (8 mg histone protein/2 ml of settled beads with a binding capacity of 20 μg biotin per ml resin; Thermo Scientific) as described [19].

2.6 Biotinylation of H4K16C by maleimide-PEG2-biotin

Before chemical biotinylation of H4K16C, any C16-C16 disulfide bonds between two H4K16C molecules were reduced with 5 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) at room temperature for 30 min; TCEP was then removed using a desalting column. The sole cysteine residue in H4K16C was biotinylated using a 20-fold molar excess of the sulfhydryl-reactive reagent maleimide-PEG2-biotin (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to produce H4K16Cbio. H4K16Cbio was purified with centrifuge filters (3,000 MWCO). The efficacy of chemical biotinylation was assessed by titrating unreacted C16 residues by using DyLight 800 Maleimide (Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 mg of H4K16Cbio and H4K16C were reduced with TCEP and incubtaed with DyLight 800 Maleimide overnight. Non-reacted maleimide was removed using Fluorescent Dye Removal columns (Thermo Scientific) and the degree of labeling as moles dye per mole protein was calculated by quantifying the absorbance at 280 nm and 777 nm for histone H4 and maleimide, respectively, and using molar extinction coefficients of 5120 M−1 cm−1 and 270,000 M−1 cm−1 for Histone H4 and maleimide, respectively. Titration experiments suggest that 92.5% ± 2.5% of the C16 residues in H4K16bio were biotinylated.

2.7 Histone octamer assembly

Histone octamers were assembled and purified according previous studies with some modifications [36]. Briefly, 1 mg of each histone H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 were individually denatured in unfolding buffer containing 6 M guanidine-HCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl and 5 mM DTT buffer for 1 h at 4°C. Histones were mixed in equimolar ratios (typically 100 nM each) and concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/ml either by dilution with unfolding buffer or by centrifugation. The histone mixture was dialyzed overnight at 4°C using Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes with a MWCO of 7,000 Da (Thermo Scientific) against three changes of 400 ml refolding buffer containing 2 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM Na-EDTA and 5 mM 2-ME. Octamers were separated from tetramers and dimers by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a SuperdexTM 200 HiLoad 16/60 column. SEC fractions were analyzed for purity and histone stoichiometry using SDS-PAGE and coomassie blue. Fractions containing histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 in approximately equal ratios were pooled and concentrated by centrifugation.

2.8 Reconstitution of nucleosomes

Nucleosomes were prepared as described previously [35, 36] with modifications. Briefly, histone octamers were mixed with Widom 601 DNA in equimolar concentrations in 2 M NaCl in a microdialyzer (MWCO 6000–8000) on ice for 30 min before the salt concentration was stepwise decreased to 0.5 M NaCl in buffers containing 1 M, 0.67 M, and 0.5 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5)by dialysis (2 h each, 4°C). The nucleosomes were reconstituted using the Widom 601 positioning sequence [34]. Samples were kept at 4°C for 1 h prior to dialysis against one change of 0.2 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris overnight. Finally, the buffer was changed to 10 mM Hepes-NaCl, pH 7.5, and 1 mM EDTA (one change, 200 ml) at 4°C for 3 h. Proper assembly of nucleosomes was confirmed by EMSA using 6% TBE precast gel (Invitrogen).

2.9 Atomic Force Microscopy

For AFM analysis we followed method described by Shlyakhtenko et al. [37]. Samples were analyzed in the AFM nanoimaging facility using the FemtoScan software (SPM, Russia) at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (Omaha, NE) as described [26]. The length of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer was quantified by subtracting the sum of both DNA arms from the length of free Widom 601 DNA. The calculations of DNA turns wrapped around histone octamers were based on the following assumptions. One hundred forty-seven base pairs of DNA are wound around histone octamer in 1.7 turns, i.e., 1 turn contains 86 bp of DNA [1, 38]. One base pair of DNA has a length of 0.34 nm, i.e., 1 turn equals 29 nm (86 bp x 0.34 nm). The following equation was used to calculate the number of nucleosomal DNA turn wrapped around histone octamers:

= 0.035Lwrapped around the core

= 0.035[CL− (L arm1−L arm2)]

Where CL is the contour length of free DNA and L arm1 and L arm2 are the lengths of short and long DNA arms, respectively. The angles between the DNA arms were quantified based on the intersection of the tangents of the arms [39, 40].

3. RESULTS

3.1 Preparation of chemically pure biotinylated histone H4

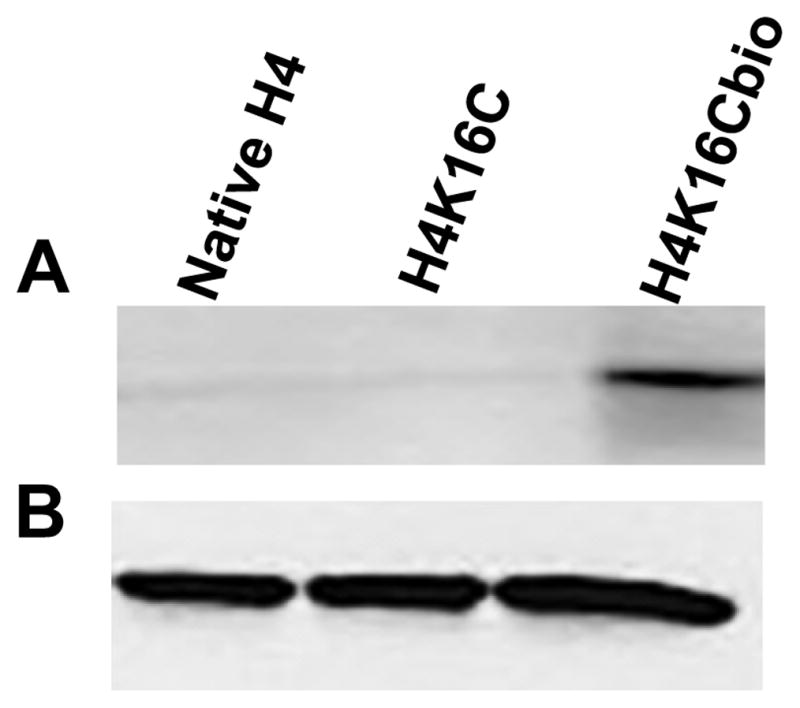

This study is based on using recombinant histones from E. coli. Our previous studies revealed that BirA in E. coli biotinylates lysine residues in histones [19], which creates a confounder in studies that depend on controlled biotinylation of distinct lysines such as K16. We succeeded in preparing biotin-free starting materials for targeted biotinylation of K16. Briefly, plasmids coding for wild-type H4 and K16-to-C16 mutant H4 (H4K16C) were created. C16 is the only cysteine residue in histone H4. Recombinant histones were purified from E. coli. A faint biotinylation signal was detectable when recombinant H4K16C was probed with anti-biotin (not shown), consistent with artifactual biotinylation by BirA. The biotinylated fraction was removed using avidin beads. When avidin-treated H4 and H4K16C probed with anti-biotin, the biotinylation signal was near background levels (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, the cysteine residue in H4K16C was biotinylated using sulfhydryl-reactive maleimide-PEG2-biotin, leading to biotinylation of C16 in H4K16Cbio. Equal loading was confirmed using an antibody to the non-modified N-terminus in histone H4 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Chemical biotinylation and integrity of histone H4.

(A) Recombinant native histone H4, mutant H4 (H4K16C), and chemically biotinylated H4 (H4K16Cbio) were probed with anti-biotin. (B) Integrity and equal loading was confirmed using anti-H4.

3.2 Nucleosome reconstitution

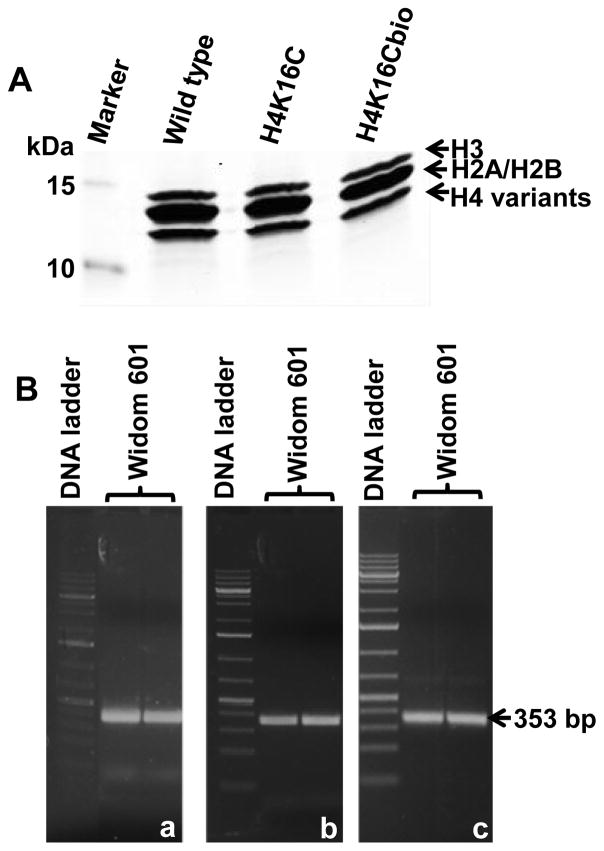

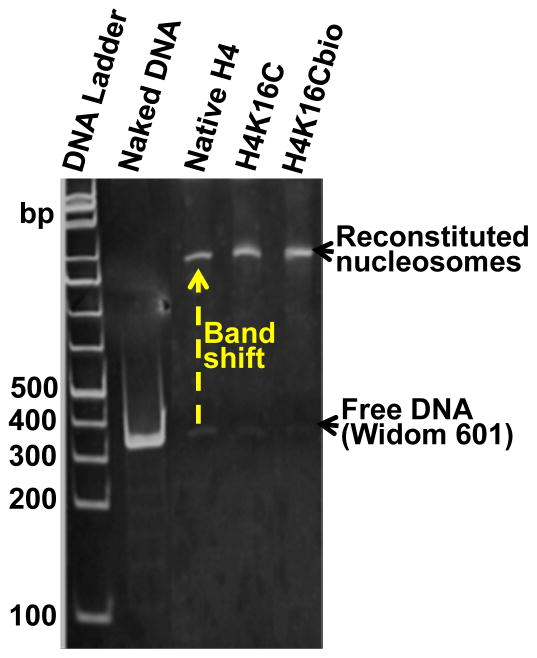

Histones H2A, H2B and H3 were also expressed and purified from E. coli. Nucleosomes were reconstituted with Widom 601 nucleosomal positioning DNA using H4K16Cbio or non-biotinylated controls (H4 and H4K16C) and equal amounts of H2A, H2B, and H3. Histone octamers were purified by size exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex ™ 200 column (GE Healthcare, USA) and an ÄKTA liquid chromatography system, and their stoichiometry was confirmed using SDS-PAGE (Fig 3A). The size and integrity of Widom 601 nucleosomal DNA was using 1% agarose gels (Fig. 3B). Nucleosomes were reconstituted and analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to confirm integration of all three histone octamer variants into nucleosomes prior to AFM analysis (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Purified core histone proteins and nucleosomal DNA.

(A) Histone octamers were reconstituted using H4, H4K16C, or H4K16Cbio and stoichiometry was demonstrated using SDS-PAGE and staining with coomassie blue. (B) The size, purity, and integrity of the Widom 601 nucleosomal position sequence was assayed after PCR (a), after extraction with phenol-chloroform precipitation with ethanol (b), and after the final agarose gel purification step (c).

Figure 4. Nucleosomal reconstitution.

Successful reconstitution of nucleosomes was confirmed using electrophoretic mobility shift assay and staining with ethidium bromide.

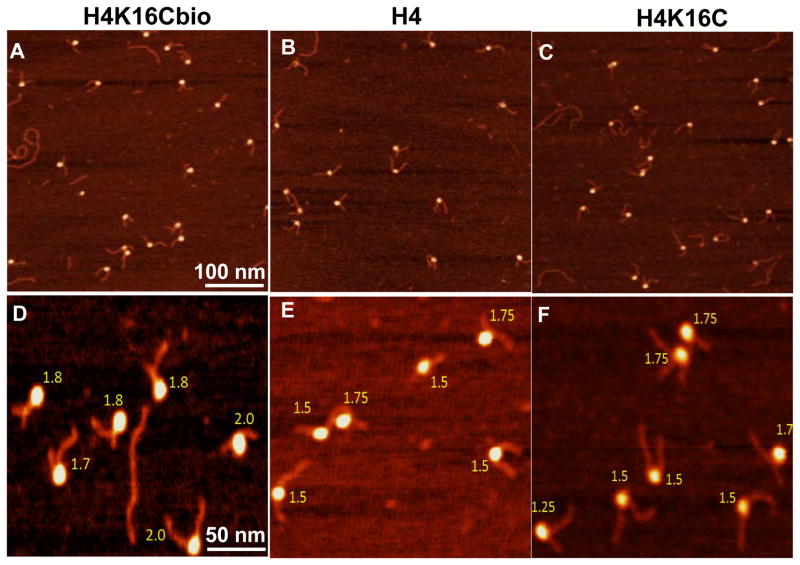

3.3 Condensation state of mononucleosomes containing H4K16Cbio, H4, and H4K16C

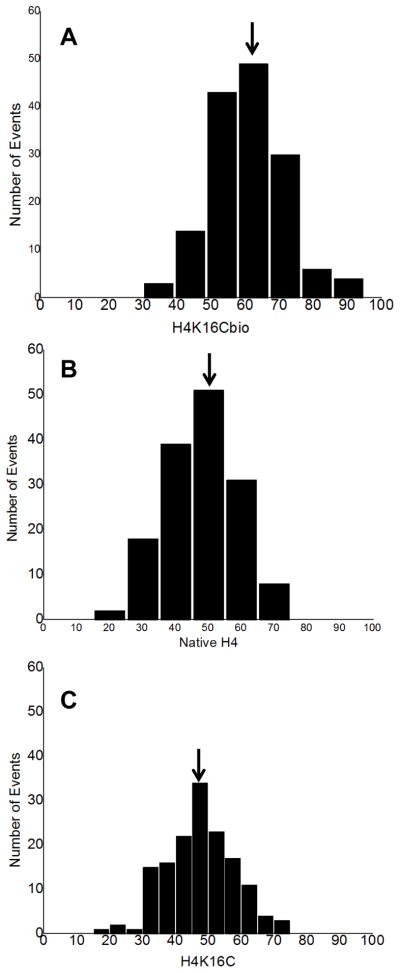

The condensation state of mononucleosomes, judged by the length of nucleosomal DNA (nsDNA) wrapped around octamers, was calculated by subtracting the lengths of both free DNA arms (in nm) protruding from the nucleosomal surface from the total length of naked DNA (see Figs. S1B and S1C in SI) and by quantifying the number of DNA turns around an octamer (judged by the angle between two DNA arms) [30, 32]. For each of the three types of octamers (H4K16Cbio, H4K16C, and H4), 150 nucleosomes were analyzed and the experiment was repeated using an independent set of samples analyzed. The length of nsDNA wrapped around an octamer was significantly greater for nucleosomes containing H4K16Cbio (61.14±10.92 nm) compared with H4 (46.89±12.6 nm) and H4K16C (47.26±10.32 nm) (P <0.001, N=150, experiment 1) (Fig. 5); H4 and H4K16C were not significantly different from each other (P >0.05). Experiment 2 produced essentially the same results: 59.49±10.67 nm for H4K16Cbio versus 47.65±10.1 nm for H4 versus 47.58±9.85 nm for H4K16C (P <0.001 biotinylated vs. non-biotinylated octamers; P >0.05 for the two non-biotinylated octamers, N=150). The difference in the length of nsDNA (~40 bp) translates into about ~0.34 turns of DNA, assuming that 1 nm equals about ~2.9 bp and that 86 bp make one turn [1, 2].

Figure 5. Length of nucleosomal DNA in biotin-defined nucleosomes.

Nucleosomes were reconstituted using H4K16Cbio (A), native H4 histone (B), or H4K16C mutant (C) and the length of DNA bound per nucleosome was quantified using AFM.

Similar findings were obtained when chromatin condensation was assessed by using the rotation angle (α°) of the two DNA ends in Widom 601 as marker. Using this independent experimental approach, we confirmed that chromatin condensation depends on histone biotinylation (Fig. 6; note the variation in scale). The number of turns was significantly higher in nucleosomes containing H4K16Cbio (1.78±0.16) compared with H4 (1.52±0.16) and H4K16C (1.52±0.21) (P <0.001; N=150, experiment 1); H4 and H4K16C were not significantly different from each other (P >0.05). Experiment 2 produced essentially the same results: 1.77±0.17 turns for H4K16Cbio versus 1.51±0.21 turns for H4 versus 1.5±0.18 turns for H4K16C (P <0.001 biotinylated vs. non biotinylated octamers; P >0.05 for the two non-biotinylated octamers; N = 150).

Figure 6. AFM scans for reconstituted nucleosome particles.

Nucleosomes were reconstituted with histones H4K16Cbio (A), H4 (B), and H4K16C (C). Images were acquired using the NanoScope IIId AFM system. Scan sizes are 500nmx500nm. Representation of enlarged AFM scans for nucleosome core reconstituted with histones H4K16Cbio (D), H4 (E), and H4K16C (F). Scan sizes are 200 nm x 200 nm.

Collectively, two approaches for assessing biotin-dependent condensation of chromatin produced similar results. When judged by DNA length, H4K16Cbio-containing nucleosomes contained ~30% more DNA than controls (Table 1). When judged by rotation angle, H4K16Cbio-containing nucleosomes contained ~17.2% more DNA than controls (see Discussion). Differences between H4 and H4K16C nucleosomes were negligible.

Table 1.

Percentage changes in length of DNA and the number of nucleosomal turns for DNA in nucleosomes reconstituted using H4K16Cbio compared with native H4 and H4K16C.

| Sample | Analytical procedure | |

|---|---|---|

| DNA length | DNA turns | |

| Percent increase (%) | ||

| Experiment # 1 | ||

| H4K16Cbio vs H4 | 30.4 | 17.1 |

| H4K16Cbio vs H4K16C | 29.4 | 17.1 |

| Experiment # 2 | ||

| H4K16Cbio vs H4 | 24.8 | 17.2 |

| H4K16Cbio vs H4K16C | 25.0 | 18.0 |

4. DISCUSSION

Here we report for the first time that biotinylation of K16 in histone H4 produces a detectable condensation of nucleosomes. This finding is consistent with previous observations that K16 plays a crucial role in the regulation of nucleosomal compaction [13]. Our study is significant for a couple of reasons. First, it offers a mechanistic explanation for gene repression by biotin-dependent epigenetic events [17, 18, 22, 24, 25] and for the strong phenotypes elicited by HLCS knockdown in fruit flies and in human cell cultures [21, 22]. Second, it introduces AFM to the research community as a tool for assessing nucleosomal compaction in response to posttranslational modifications of histones though the use of site-directed mutagenesis and chemical modifications. Our studies provide evidence that AFM has the sensitivity to detect changes as subtle as 13% [26].

We and others have consistently maintained the opinion that biotinylation of histones is a rare event, and that only less than 0.001% of histones H3 and H4 are biotinylated in humans [5, 8, 27]. A recent proposal that histone biotinylation is not a natural modification [41] was extensively rebutted [8]. In the light of the rarity of histone modifications we proposed that the effects of biotin in gene repression at the chromatin level are mediated through the HLCS-dependent assembly of a multiprotein complex in chromatin [8]. Some members of this complex have been identified and include histone methyltransferases and histone deacetylases (unpublished observation). According to this model, biotinylation marks in the epigenome are primarily marks for HLCS docking sites in chromatin. This is consistent with previous observations that HLCS interacts physically with histones, that recombinant HLCS has histone biotin ligase activity, that both full-length and N-truncated HLCS can enter the nuclear compartment, and that HLCS, if fused to DNA adenosine methyltransferase, creates adenosine methylation marks in human cells [20, 24, 42–44]. Importantly, the expression of HLCS and its nuclear translocation are lower in biotin-deficient rats and cell cultures than in biotin-sufficient controls [24, 45, 46], thereby establishing a link between biotinylation of histones and biotin nutrition.

This paper provides evidence that biotinylation of histones contributes moderately to gene repression through facilitating chromatin condensation, and that biotinylation of K16 had an effect up to 17% greater than that observed for biotinylation of K12 [26]. Presumably, these effects are moderate regarding the overall biological effect compared to those of the HLCS-containing protein complex. Despite the rarity of histone biotinylation marks in the epigenome, we propose that direct effects of biotinylation should not be disregarded. For example, biotinylation marks are enriched in repeat regions such as pericentromeric alpha satellite repeats, telomeres, and long terminal repeats [22, 25, 47] where they might contribute to transcriptional repression. Also, the mere abundance of histone modification marks does necessarily predict biological significance. For example, serine-14 phosphorylation in histone H2B and histone poly(ADP-ribosylation) are detectable only after induction of apoptosis and major DNA damage, respectively, but the role of these epigenetic marks in cell stress and death is unambiguous [48–50].

One might ask the question why a cysteine residue was chosen to substitute for lysine in H4K16C. The answer to this question is straightforward. The artificial cysteine-16 is the only sulfhydryl-containing amino acid in the entire H4 molecule. Therefore, one can specifically target the biotin modification to amino acid residue 16 by using the sulfhydryl-specific reagent maleimide-PEG2-biotin. In contrast, histones contain numerous lysine and arginine residues. It is not feasible to specifically target one of these residues by chemical or enzymatic approaches without non-specifically biotinylating multiple amino acid residues. We conclude that biotinylation of K16 in histone H4 contributes toward chromatin condensation and gene repression, and that this effect synergizes with the HLCS-dependent assembly of a gene repression complex.

Supplementary Material

(A) The nucleosome position sequence in the Widom 601 sequence (shown in red) is flanked by two arms of different lengths (79 bp and 127 bp respectively, shown in green) for a total length of 353 bp (B). Representative AFM scans for purified naked Widom 601 DNA used to verify the length of DNA. Dotted lines shows the length (~120 nm) expected for 353bp. (C) Distribution and most probable value Xc of Widom 601 DNA prior to nucleosomal reconstitution.

Histograms were fitted based on the assumption of a Gaussian distribution of nsDNA, which was calculated from the length of DNA arms. A = H4K16Cbio, B = native H4, and C =H4K16C.

Highlights.

Biotinylation of K16 in histone H4 contributes toward nucleosome condensation.

Effects of histone biotinylation are quantitatively minor.

Mutagenesis plus AFM allow for quantifying histone modification effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Lyubchenko and L. S. Shlyakhtenko from the AFM Nano-imaging facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, NE, for their help with AFM analysis. A contribution of the University of Nebraska Agricultural Research Division, supported in part by funds provided through the Hatch Act. Additional support was provided by NIH grants DK063945, DK077816 and ES015206; USDA grant 2006-35200-17138; and by NSF grant EPS- 0701892.

Abbreviations

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- 2-ME

β-mercaptoethanol

- C

cysteine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- Guanidine-HCl

guanidine hydrochloride

- HLCS

holocarboxylase synthetase

- K

lysine

- MWCO

Molecular Weight Cut Off

- NCP

nucleosomal core particle

- nsDNA

nucleosomal DNA

- PBS

Phosphate Buffered Saline

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium Dodecyle Sulphate-Poly Acrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- TBE

tris-borate EDTA

- TCEP

tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–60. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartke T, Vermeulen M, Xhemalce B, Robson SC, Mann M, Kouzarides T. Nucleosome-interacting proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation. Cell. 2010;143:470–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews AJ, Luger K. A coupled equilibrium approach to study nucleosome thermodynamics. Methods Enzymol. 2011;488:265–85. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381268-1.00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley JS, Griffin JB, Zempleni J. Biotinylation of histones in human cells: effects of cell proliferation. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5424–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–83. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camporeale G, Shubert EE, Sarath G, Cerny R, Zempleni J. K8 and K12 are biotinylated in human histone H4. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2257–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuroishi T, Rios-Avila L, Pestinger V, Wijeratne SS, Zempleni J. Biotinylation is a natural, albeit rare, modification of human histones. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:537–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tremethick DJ. Higher-order structures of chromatin: the elusive 30 nm fiber. Cell. 2007;128:651–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullgrabe J, Kavanagh E, Joseph B. Histone onco-modifications. Oncogene. 2011;30:3391–403. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allfrey VG, Faulkner R, Mirsky AE. Acetylation and Methylation of Histones and Their Possible Role in the Regulation of Rna Synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;51:786–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kouzarides T, Berger SL. Chromatin modifications and their mechanism of action. In: Allis CD, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D, editors. Epigenetics. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shogren-Knaak M, Ishii H, Sun JM, Pazin MJ, Davie JR, Peterson CL. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311:844–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shogren-Knaak M, Peterson CL. Switching on chromatin: mechanistic role of histone H4-K16 acetylation. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1361–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.13.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gansen A, Toth K, Schwarz N, Langowski J. Structural variability of nucleosomes detected by single-pair Forster resonance energy transfer: histone acetylation, sequence variation, and salt effects. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:2604–13. doi: 10.1021/jp7114737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takechi R, Taniguchi A, Ebara S, Fukui T, Watanabe T. Biotin deficiency affects the proliferation of human embryonic palatal mesenchymal cells in culture. J Nutr. 2008;138:680–4. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pestinger V, Wijeratne SSK, Rodriguez-Melendez R, Zempleni J. Novel histone biotinylation marks are enriched in repeat regions and participate in repression of transcriptionally competent genes. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22:328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rios-Avila L, Pestinger V, Zempleni J. K16-biotinylated histone H4 is overrepresented in repeat regions and participates in the repression of transcriptionally competent genes in human Jurkat lymphoid cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.10.009. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobza K, Sarath G, Zempleni J. Prokaryotic BirA ligase biotinylates K4, K9, K18 and K23 in histone H3. BMB Reports. 2008;41:310–5. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.4.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bao B, Pestinger V, IHY, Borgstahl GEO, Kolar C, Zempleni J. Holocarboxylase synthetase is a chromatin protein and interacts directly with histone H3 to mediate biotinylation of K9 and K18. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22:470–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camporeale G, Giordano E, Rendina R, Zempleni J, Eissenberg JC. Drosophila holocarboxylase synthetase is a chromosomal protein required for normal histone biotinylation, gene transcription patterns, lifespan and heat tolerance. J Nutr. 2006;136:2735–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.11.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew YC, West JT, Kratzer SJ, Ilvarsonn AM, Eissenberg JC, Dave BJ, et al. Biotinylation of histones represses transposable elements in human and mouse cells and cell lines, and in Drosophila melanogaster. J Nutr. 2008;138:2316–22. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.098673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith EM, Hoi JT, Eissenberg JC, Shoemaker JD, Neckameyer WS, Ilvarsonn AM, et al. Feeding Drosophila a biotin-deficient diet for multiple generations increases stress resistance and lifespan and alters gene expression and histone biotinylation patterns. J Nutr. 2007;137:2006–12. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gralla M, Camporeale G, Zempleni J. Holocarboxylase synthetase regulates expression of biotin transporters by chromatin remodeling events at the SMVT locus. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camporeale G, Oommen AM, Griffin JB, Sarath G, Zempleni J. K12-biotinylated histone H4 marks heterochromatin in human lymphoblastoma cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:760–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filenko NA, Kolar C, West JT, Hassan YI, Borgstahl GEO, Zempleni J, et al. The role of histone H4 biotinylation in the structure and dynamics of nucleosomes. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey LM, Ivanov RA, Wallace JC, Polyak SW. Artifactual detection of biotin on histones by streptavidin. Anal Biochem. 2008;373:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zempleni J, Wijeratne SSK, Kuroishi T. Biotin. In: Erdman JW Jr, Macdonald I, Zeisel SH, editors. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. Vol. 10. International Life Sciences Institute; Washington, D.C: 2012. pp. 587–609. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camporeale G, Zempleni J, Eissenberg JC. Susceptibility to heat stress and aberrant gene expression patterns in holocarboxylase synthetase-deficient Drosophila melanogaster are caused by decreased biotinylation of histones, not of carboxylases. J Nutr. 2007;137:885–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shlyakhtenko LS, Lushnikov AY, Lyubchenko YL. Dynamics of nucleosomes revealed by time-lapse atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7842–8. doi: 10.1021/bi900977t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyubchenko YL, Shlyakhtenko LS, Gall AA. Atomic force microscopy imaging and probing of DNA, proteins, and protein DNA complexes: silatrane surface chemistry. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;543:337–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-015-1_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyubchenko YL, Shlyakhtenko LS. AFM for analysis of structure and dynamics of DNA and protein-DNA complexes. Methods. 2009;47:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thastrom A, Lowary PT, Widlund HR, Cao H, Kubista M, Widom J. Sequence motifs and free energies of selected natural and non-natural nucleosome positioning DNA sequences. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:213–29. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Richmond TJ. Preparation of nucleosome core particle from recombinant histones. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:3–19. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyer PN, Edayathumangalam RS, White CL, Bao Y, Chakravarthy S, Muthurajan UM, et al. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shlyakhtenko LS, Gall AA, Filonov A, Cerovac Z, Lushnikov A, Lyubchenko YL. Silatrane-based surface chemistry for immobilization of DNA, protein-DNA complexes and other biological materials. Ultramicroscopy. 2003;97:279–87. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(03)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng J, Chun-Cheng Z. Thermodynamics of nucleosomal core particles. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2594–8. doi: 10.1021/bi061138i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pavlicek JW, Oussatcheva EA, Sinden RR, Potaman VN, Sankey OF, Lyubchenko YL. Supercoiling-induced DNA bending. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10664–8. doi: 10.1021/bi0362572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lushnikov AY, Potaman VN, Oussatcheva EA, Sinden RR, Lyubchenko YL. DNA strand arrangement within the SfiI-DNA complex: atomic force microscopy analysis. Biochemistry. 2006;45:152–8. doi: 10.1021/bi051767c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Healy S, Perez-Cadahia B, Jia D, McDonald MK, Davie JR, Gravel RA. Biotin is not a natural histone modification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:719–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bao B, Wijeratne SS, Rodriguez-Melendez R, Zempleni J. Human holocarboxylase synthetase with a start site at methionine-58 is the predominant nuclear variant of this protein and has catalytic activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh D, Pannier AK, Zempleni J. Identification of holocarboxylase synthetase chromatin binding sites using the DamID technology. Anal Biochem. 2011;413:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey LM, Wallace JC, Polyak SW. Holocarboxylase synthetase: correlation of protein localisation with biological function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;496:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez-Melendez R, Cano S, Mendez ST, Velazquez A. Biotin regulates the genetic expression of holocarboxylase synthetase and mitochondrial carboxylases in rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:1909–13. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.7.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaur Mall G, Chew YC, Zempleni J. Biotin requirements are lower in human Jurkat lymphoid cells but homeostatic mechanisms are similar to those of HepG2 liver cells. J Nutr. 2010;140:1086–92. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.121475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijeratne SS, Camporeale G, Zempleni J. K12-biotinylated histone H4 is enriched in telomeric repeats from human lung IMR-90 fibroblasts. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung WL, Ajiro K, Samejima K, Kloc M, Cheung P, Mizzen CA, et al. Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell. 2003;113:507–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boulikas T. At least 60 ADP-ribosylated variant histones are present in nuclei from dimethylsulfate-treated and untreated cells. EMBO J. 1988;7:57–67. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boulikas T. DNA strand breaks alter histone ADP-ribosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3499–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) The nucleosome position sequence in the Widom 601 sequence (shown in red) is flanked by two arms of different lengths (79 bp and 127 bp respectively, shown in green) for a total length of 353 bp (B). Representative AFM scans for purified naked Widom 601 DNA used to verify the length of DNA. Dotted lines shows the length (~120 nm) expected for 353bp. (C) Distribution and most probable value Xc of Widom 601 DNA prior to nucleosomal reconstitution.

Histograms were fitted based on the assumption of a Gaussian distribution of nsDNA, which was calculated from the length of DNA arms. A = H4K16Cbio, B = native H4, and C =H4K16C.