Abstract

Background

Women undergoing induced abortion may be more motivated to choose long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including the intrauterine device (IUD) and implant, than women without a history of abortion. Our objective was to determine whether the contraceptive method chosen is influenced by a recent history of induced abortion and access to immediate postabortion contraception.

Study Design

This was a sub-analysis of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. We compared contraception chosen by women with a recent history of abortion to women without a recent history. Participants with a recent history of abortion were divided into immediate postabortion contraception and delayed-start contraception groups.

Results

Data were available for 5083 women; 3410 women without a recent abortion history, 937 women who received immediate postabortion contraception, and 736 women who received delayed-start postabortion contraception. Women offered immediate postabortion contraception were more than 3 times as likely to choose an IUD (RRadj 3.30, 95%CI 2.67–4.85) and 50% more likely to choose the implant (RRadj 1.51, 95%CI 1.12–2.03) compared to women without a recent abortion. There was no difference in contraceptive method selected among women offered delayed-start postabortion contraception compared to women without a recent abortion.

Conclusion

Women offered immediate postabortion contraception are more likely to choose the IUD and implant than women without a recent abortion history. Increasing access to immediate postabortion LARC is essential to preventing repeat unintended pregnancies.

1. Introduction

Unintended pregnancy is a significant public health problem in the United States with over 3 million unintended pregnancies occurring annually [1]. More than 40% of these unintended pregnancies will result in induced abortion [2]. There are multiple factors associated with this high rate of unintended pregnancy including incorrect or inconsistent use of contraception [3]. More than half of women obtaining an induced abortion report using contraception in the month prior to the unintended pregnancy [4]. Users of oral contraceptives pills (OCPs), depo-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA), and condoms have high discontinuation rates; up to 33% of women will discontinue one of these methods within 6 months of initiation for a method-related reason [5]. One study attributed 20% of all unintended pregnancies to OCP discontinuation alone [6].

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the intrauterine device (IUD) and subdermal implant, is highly effective with typical failure rates of less than 1% [7]. While use of the IUD has recently increased among contracepting women in the U.S. from 2% to 5.5%, uptake remains lower than the use of less effective methods such as condoms and OCPs [8].

Women undergoing an induced abortion are at increased risk for a subsequent unintended pregnancy, and repeat abortions account for 47% of all abortions in the United States [9]. The experience of abortion may make women more likely to contracept and more likely to choose highly effective methods. A recent French survey found that 54% of women undergoing induced abortion switched to a more effective method after the abortion; however, 14% changed to a less effective method or no method at all [10]. Uptake of highly effective methods of contraception at the time of unintended pregnancy has the potential to decrease the number of repeat unintended pregnancies; a study published by Goodman et al. [11] found that women who received immediate postabortion IUDs were 63% less likely to present for a repeat abortion. Additionally, a return visit for an IUD insertion has been identified as a barrier to postabortion uptake of the IUD [12]. Women offered immediate postabortion insertion of IUDs and implants may be more likely to choose these methods than women offered delayed-start of these methods.

We hypothesized that, when cost and access are removed as potential barriers, women with a recent history of induced abortion will be more likely to choose the IUD and subdermal implants than women without a recent abortion history. We also hypothesized that, among women with a recent abortion history, access to immediate postabortion contraception would be associated with increased uptake of IUDs and implants compared to women who are offered delayed-start of the contraceptive method.

2. Materials and methods

This study was a planned secondary analysis of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE), which is an on-going, prospective cohort study enrolling 10,000 women in the St. Louis area. The study is designed to promote the use of long-acting, reversible methods of contraception (LARC), remove financial barriers to contraception, and evaluate continuation and satisfaction for reversible methods. We provide each participant with the reversible contraceptive method of her choice at no cost to her. Participants then complete follow-up surveys by telephone with a member of the study team at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months post-enrollment. Participants are recruited at specific clinic locations and via general awareness about CHOICE through their medical providers, posters, study flyers, and word of mouth. Recruitment sites include local private obstetrician-gynecologists, university-affiliated clinics, two clinics providing abortion services, and community clinics that provide family planning, obstetric, gynecologic, and/or primary care. Women are eligible to participate if they are 14–45 years of age, reside in St. Louis City or County, have been sexually active with a male partner in the past six months or anticipate sexual activity in the next six months, have not had a tubal sterilization or hysterectomy, do not desire pregnancy in the next year, and are interested in starting a new reversible contraceptive method. We obtained approval from the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office prior to recruitment of participants. We have described the methods of this study previously [12]. Women in this analysis were enrolled between August 2007 and December 2009.

At the baseline enrollment visit, we administered a survey to participants which collects comprehensive information on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, past and current reproductive history including contraceptive experience (e.g., continuation, side effects, reasons for discontinuation or non-compliance, and satisfaction), prior pregnancies, sexual behavior, and history of sexually transmitted infections (STI). We also offered testing for STI including Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis, syphilis, and HIV. Once the participant had completed the survey and undergone STI testing, we provided her with her chosen contraceptive method.

In this analysis, we compared the contraceptive method chosen at the time of enrollment into CHOICE between women with and without a recent history of induced abortion. We defined participants as having a recent abortion history if they had a medical or surgical abortion procedure 90 days or less prior to enrolling into CHOICE or up to 30 days after enrolling into CHOICE. We chose this time frame as it captured greater than 95% of recent abortions reported by participants.

Women in the recent abortion group were further divided into “immediate” and “delayed-start” postabortion contraception groups based on the timing of their abortion relative to enrollment into CHOICE. All women who underwent an abortion on or after the day of enrollment received contraception on the same day as the abortion and were considered in the “immediate” postabortion contraception group. Women who received their contraceptive method the day following the abortion or later were considered “delayed-start.” There were 196 women who underwent medication abortion; these women were all assigned to the delayed-start group as they were not eligible to start all reversible contraceptive methods on the same day as the abortion. Abortion history was obtained by self-report. We were able to confirm the abortion procedure in all women in the immediate postabortion contraception group.

We compared demographic, socioeconomic and behavioral characteristics for the women in the 3 groups. Comparisons were made using chi-square for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Preliminary analyses suggested that women who chose the IUD and implant differed in baseline characteristics. Therefore, we performed univariate and multivariable multinomial logistic regression to investigate the contraceptive method chosen at enrollment as 3 categories. We examined choice of the IUD or implant and compared this to the choice of other reversible methods including OCPs, the vaginal ring, the contraceptive patch, and DMPA. There were only 5 women who chose a barrier method and these women were excluded from further analyses. We planned to include history of recent abortion in the multivariable model regardless of whether it was significant in the univariate model because this was our a priori hypothesis. All other covariates which were significant in the univariate analysis were also included in the multivariable model. We performed all statistical analyses using STATA 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

3. Results

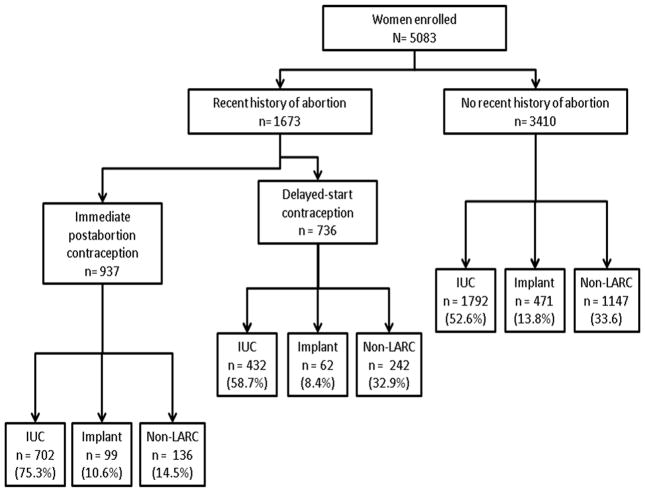

Data were available for 5083 CHOICE participants for this analysis. There were 3410 (67.1%) women without a recent abortion history and 1673 (32.9%) women who had undergone at induced abortion in the prior 90 days. Of the women with a recent abortion history, 937 were offered immediate postabortion contraception and 736 were offered delayed-start of their contraceptive method. In the delayed-start group, the time between the abortion and enrollment ranged from 1 to 90 days with a mean length of 32 days (SD 22 days). Fig. 1 diagrams participants by recent abortion history and shows the contraceptive methods chosen by the 3 groups. Rates of unintended pregnancy were high among our cohort; 3657 (71.9%) women reported at least one prior pregnancy and of the women with a previous pregnancy, 3359 (91.9%) reported at least one prior unintended pregnancy. Overall, 1999 (39.3%) women reported ever having had an abortion which is slightly higher than reported lifetime estimates in the United States [13]. Among the women without a recent abortion history, 783 (23.0%) reported a remote history of abortion.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing participants by their recent abortion history and the contraceptive method chosen at the

Table 1 shows the demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral characteristics for the 3 groups. The mean age was similar; however the 3 groups showed statistically significant differences in race, ethnicity, marital status, level of education, insurance status, and low socioeconomic status (SES) defined as either receiving public assistance or reporting difficulty paying for basic necessities such as food, housing, transportation, and medical care. There were also differences in parity, history of a STI, and contraceptive method chosen at enrollment. Table 1 also shows the contraceptive method selected at the time of enrollment into CHOICE.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and behavior characteristics of participants according to recent abortion history (N=5083). Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

| No recent abortion (n=3410) | Delayed-start contraception (n=736) | Immediate contraception (n=937) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 25.0 (5.8) | 25.5 (5.7) | 25.4 (5.7) | 0.05§ |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 1480 (43.6) | 404 (55.1) | 558 (59.9) | <.001 |

| White | 1650 (48.6) | 278 (37.9) | 311 (33.4) | |

| Other | 263 (7.7) | 51 (7.0) | 62 (6.7) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 183 (5.4) | 19 (2.6) | 43 (4.6) | 0.04 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 2054 (60.3) | 452 (61.4) | 591 (63.1) | <.001 |

| Married/living with a partner | 1175 (34.5) | 226 (30.7) | 261 (27.9) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 179 (5.3) | 58 (7.9) | 84 (9.0) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 407 (11.9) | 69 (9.4) | 152 (16.2) | <.001 |

| High school or equivalent | 694 (20.4) | 199 (27.0) | 299 (31.9) | |

| Some college | 1383 (40.6) | 358 (48.6) | 400 (42.7) | |

| College/Graduate school | 924 (27.2) | 110 (15.0) | 86 (9.2) | |

| Insurance | ||||

| No insurance | 1310 (38.7) | 392 (53.5) | 500 (53.9) | <.001 |

| Private | 1610 (47.6) | 290 (39.6) | 317 (34.2) | |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 462 (13.7) | 51 (7.0) | 110 (11.9) | |

| Receives public assistance or reports difficulty paying for transportation, housing, medical expenses or food in past 12 months | 1,819 (53.3) | 441 (60.0) | 623 (66.5) | <.001 |

| Behavioral characteristics | ||||

| Parity | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 1784 (52.3) | 303 (41.2) | 287 (30.6) | |

| 1–2 | 1328 (38.9) | 351 (47.7) | 477 (50.9) | |

| 3+ | 298 (8.7) | 82 (11.1) | 173 (18.5) | |

| Prior abortion* | 783 (3.0) | 736 (100.0) | 480 (50.9) | <.001 |

| Prior STI diagnosis | 1300 (38.1) | 327 (44.4) | 391 (41.7) | 0.002 |

| Contraception | ||||

| Method chosen at enrollment | <.001 | |||

| IUC | 1792 (52.6) | 432 (58.7) | 702 (74.9) | |

| LNG-IUS | 1,450 (42.5) | 340 (46.2) | 599 (63.9) | |

| Copper IUC | 342 (10.0) | 92 (12.5) | 103 (11.0) | |

| Subdermal implant | 471 (13.8) | 62 (8.4) | 99 (10.6) | |

| Pills/ring/patch | 924 (27.1) | 164 (22.3) | 75 (8.0) | |

| DMPA | 223 (6.5) | 78 (10.6) | 61 (6.5) | |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

ANOVA

Does not include any abortion performed after enrollment

STI – sexually transmitted infection

IUC – intrauterine contraception

IUS – intrauterine system

DMPA – depo-medroxyprogesterone

Women with any recent abortion history were almost twice as likely to choose the IUD compared to women without a recent abortion history (RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.67–2.20); however, they were not more likely to choose the implant (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.84–1.28). Table 2 shows the results of the univariate and multivariable analyses. In the univariate analysis, women offered immediate postabortion contraception were more than 3 times more likely to choose an IUD compared to women without a recent abortion history (RR 3.30, 95%CI 2.71–4.03). Women who were offered delayed-start of their contraceptive method were not any more likely to choose the IUD than women without a recent abortion history (RR 1.14, 95%CI 0.96–1.36).

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with the choice of intrauterine device or implant compared to other contraceptive methods (oral contraceptives, contraceptive ring, contraceptive patch and depo-medroxyprogesterone) as baseline contraceptive method.

| Univariate analysis Relative Risk (95%Confidence Interval) | Multivariable analysis* Relative Risk (95%Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUC (n=2926) | Implant (n=632) | IUC (n=2926) | Implant (n=632) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| <21 | 0.55 (0.47–0.65) | 1.82 (1.48–2.23) | 0.76 (0.62–0.92) | 1.32 (1.01–1.72) |

| 21–29 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 30–45 | 1.94 (1.63–2.32) | 1.29 (0.97–1.72) | 1.41 (1.15–1.72) | 1.17 (0.85–1.60) |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 0.93 (0.82–1.06) | 1.34 (1.10–1.64) | 0.61 (0.52–0.72) | 0.91 (0.72–1.14) |

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Other | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) | 1.20 (0.84–1.73) | 0.81 (0.62–1.05) | 1.09 (0.75–1.58) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.00 (0.84–1.20) | 0.92 (0.73–1.14) | 1.15 (0.82–1.62) | 0.86 (0.55–1.34) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Married/living with a partner | 2.03 (1.76–2.33) | 1.35 (1.10–1.67) | 1.38 (1.18–1.62) | 1.33 (1.05–1.68) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 2.09 (1.58–2.76) | 1.15 (0.74–1.78) | 0.96 (0.70–1.30) | 1.07 (0.66–1.72) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 0.79 (0.63–1.00) | 1.82 (1.37–2.41) | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) | 1.74 (1.28–2.36) |

| High school or equivalent | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Some college | 0.84 (0.71–0.98) | 0.56 (0.44–0.72) | 1.03 (0.86–1.24) | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) |

| College/Graduate school | 0.81 (0.67–0.97) | 0.36 (0.26–0.49) | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) | 0.54 (0.38–0.78) |

| Insurance | ||||

| No insurance | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Private | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 0.73 (0.60–0.90) | 1.34 (1.16–1.58) | 0.94 (0.73–1.19) |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 2.39 (1.87–3.06) | 4.02 (2.98–5.41) | 2.35 (1.80–3.00) | 2.92 (2.11–4.01) |

| Receives public assistance or reports difficulty paying for transportation, housing, medical expenses or food in past 12 months | 1.59 (1.40–1.80) | 1.71 (1.41–2.07) | 1.10 (0.94–1.30) | 1.19 (0.93–1.52) |

| Behavioral characteristics | ||||

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 1–2 | 3.06 (2.67–3.51) | 1.80 (1.48–2.20) | 2.58 (2.16–3.07) | 1.29 (0.99–1.67) |

| 3+ | 5.06 (3.92–6.55) | 2.30 (1.60–3.30) | 3.48 (2.55–4.74) | 1.45 (0.93–2.27) |

| Recent abortion | ||||

| No recent abortion | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Immediate postabortion contraception | 3.31 (2.71–4.03) | 1.77 (1.34–2.35) | 3.30 (2.67–4.08) | 1.51 (1.12–2.03) |

| Delayed–start postabortion contraception | 1.14 (0.96–1.36) | 0.62 (0.46–0.84) | 1.14 (0.95–1.39) | 0.63 (0.46–0.86) |

| Any STI diagnosis in lifetime | 1.24 (1.09–1.41) | 1.09 (0.90–1.32) | 1.04 (0.90–1.21) | 0.99 (0.80–1.22) |

Adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, marital status, education level, insurance status, low SES, parity, number, history of STI, and recent history of abortion.

IUD – intrauterine device

implant – subdermal implant

STI – sexually transmitted infection

The characteristics associated with the choice of the implant were similar to the IUD in the univariate analysis, except that black race was associated with higher uptake of the implant (RR 1.35, 95%CI 1.10–1.64). Women less than 21 years of age were also more likely to choose the implant (RR 1.82, 95%CI 1.48–2.23) compared to older women. Women offered immediate postabortion contraception were 77% more likely to choose the implant than women without a recent abortion history (RR 1.77, 95%CI 1.34–2.35). Women who were offered delayed-start of their contraceptive method were almost 40% less likely to choose the implant than women who did not have a recent abortion history (RR 0.62, 95%CI 0.46–0.84)

In the multivariable multinomial logistic regression model also shown in Table 2, we adjusted for age, race, marital status, insurance status, level of education, low SES, parity, history of STI, and recent abortion history. These characteristics were all significantly associated with the choice of an IUD at enrollment except for race. Older women and married women were more likely to choose the IUD (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.15–1.72 and RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.18–1.62, respectively) compared to younger women and single women. Multiparous women were more likely to choose the IUD than nulliparous women and the effect was greater for those with 3 or more children. Women offered immediate postabortion contraception were 3 times more likely to choose the IUD (RR 3.30, 95% CI 2.67–4.08) than women without a recent abortion history. Delayed-start was not significantly associated with choice of the IUD (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.95–1.39).

Characteristics associated with choosing the implant in the multivariate model were slightly different; younger women and women with less education were more likely to choose the implant (RR 1.32, 95%CI 1.01–1.72 and RR 1.74, 95%CI 1.28–2.36, respectively) compared to older women and women with a high school level of education or greater. As education level increased, women were less likely to choose the implant. Parity was not associated with choice of the implant. Women offered immediate postabortion contraception were 50% more likely to choose the implant (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.12–2.03) than women without a recent abortion history. Women offered delayed-start were less likely to choose the implant (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.46–0.86) compared to women without a recent abortion history

In the delayed-start group, the interval between the abortion and initiation of contraception was not associated with choice of LARC. Women who reported an abortion 30 to 60 days and 61 to 90 days prior to contraceptive initiation chose LARC at similar rates compared to women who reported an abortion 1 to 30 days prior to contraceptive initiation (0.87, 95%CI 0.62–1.22 and OR 0.71, 95%CI 0.44–1.14, respectively).

4. Discussion

Our results show that women undergoing induced abortion who have access to immediate postabortion contraception are more likely to choose LARC than women who are not having abortions or women undergoing abortion without complete access to immediate postabortion contraception.. Access to immediate postabortion contraception appears to be a critical factor in postabortion contraceptive decision-making and women with access to all reversible options immediately postabortion are more likely to choose IUD and the implant than women without a recent abortion history. One possible explanation is that these women are already undergoing a surgical procedure and find insertion of a LARC method to be more acceptable as it is not perceived as a separate procedure. The finding that women who had had access to immediate postabortion contraception were more likely to choose the IUD than the implant further supports this hypothesis as women having a surgical abortion are already undergoing an intrauterine procedure.

Another possible explanation for the observed effect of abortion history on contraceptive decision-making is that women undergoing abortion are more motivated to choose highly effective contraception, but this motivation decreases over time. Prior studies randomizing women to immediate versus delayed insertion of the IUD show higher rates of successful IUD insertion in women randomized to immediate postabortion insertion [14]. In our study, we did not find an association between the time from the abortion to contraceptive initiation and uptake of LARC. These findings underscore the importance of offering immediate postabortion insertion of LARC methods to women undergoing induced abortion.

The CHOICE Project decreases barriers to IUD use in several ways; 1) we remove the financial barriers to contraceptive methods; 2) we provide comprehensive counseling which includes discussion of all reversible methods; and 3) we offer IUDs to all women without a medical contraindication. All of these interventions contribute to the high uptake of IUDs in our study. Given our study design, it is not possible to know if any single intervention is the most effective intervention, although our study findings certainly suggest that the removal of these barriers leads to a significant increase in the uptake of LARC.

This study has several strengths including a large sample size with a racially and socioeconomically diverse population which makes our findings generalizable to other urban settings. Additionally, we were able to remove cost and access as potential barriers to contraceptive choice; thereby allowing us to see which reversible contraceptive method was truly preferred, not the method that was offered, that was available, or that the woman could afford.

This study is not without limitations. Since women were not randomized to immediate versus delayed postabortion contraception, it is possible that there were different baseline characteristics between the groups which may have affected their contraceptive decisions. We did control for potential confounding in our multivariable model and found that the relative risks for contraceptive method chosen did not differ significantly between the univariate and multivariable models in the immediate postabortion contraception group. Additionally, we have an extremely high uptake of IUDs and implants in our CHOICE cohort. It is possible that in other settings, women with a recent abortion history may be more likely to choose LARC than women without a recent abortion, but in our study this effect was masked due to the high uptake of LARC in both groups. Another possible limitation is that abortion history was gathered by self-report which has shown to result in an underestimation in other studies [16]. However, in our study the prevalence of abortion was 39%, which is higher than the national average, suggesting that underreporting was not an issue.

The results of this study have important implications for health policy. Offering immediate postabortion LARC is an essential strategy to decrease the number of repeat abortions. However, there are many barriers to the provision of immediate postabortion LARC, including insurance reimbursement and provider misinformation. A survey of National Abortion Federation providers found that immediate postabortion LARC had not been routinely integrated into clinical abortion services and that there were barriers to provision including reimbursement, clinic flow issues, and limited provider familiarity with LARC methods [17]. Our results reinforce the importance of offering immediate postabortion LARC and are consistent with other published studies that have found women prefer immediate postabortion insertion of IUD rather than delayed insertion [12]. Increasing access to immediate postabortion LARC should be a priority to decrease the incidence of unintended pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by: 1) an anonymous foundation; 2) Midcareer Investigator Award in Women’s Health Research (K24 HD01298); 3) Award number K12HD001459 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD); and 4) Award number KL2RR024994 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NICHD, NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RK, Zolna MR, Henshaw SK, Finer LB. Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services 2005. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40:6–16. doi: 10.1363/4000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost JJ, Darroch JE. Factors associated with contraceptive choice and inconsistent method use, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40:94–104. doi: 10.1363/4009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Contraceptive use among U.S. women having abortions in 2000–2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:294–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trussell J, Vaughan B. Contraceptive failure, method-related discontinuation and resumption of use: results from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:64–72. 93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Long S. Unintended pregnancies and use, misuse and discontinuation of oral contraceptivies. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:355–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trussell J. Contraceptive Efficacy. In: Hatcher RATJ, Nelson ALCC, Guest F, Kowal D, editors. Contraceptive Technology. New York (NY): Ardent Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2010;29:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones RK, Kost K, Singh S, Henshaw SK, Finer LB. Trends in abortion in the United States. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:119–29. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181a2af8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreau C, Trussell J, Desfreres J, Bajos N. Patterns of contraceptive use before and after an abortion: results from a nationally representative survey of women undergoing an abortion in France. Contraception. 2010;82:337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman S, Hendlish SK, Reeves MF, Foster-Rosales A. Impact of immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine contraception on repeat abortion. Contraception. 2008;78:143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanek AM, Bednarek PH, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Edelman AB. Barriers associated with the failure to return for intrauterine device insertion following first-trimester abortion. Contraception. 2009;79:216–20. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: Reducing Barriers to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:24–9. 46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF, Stanwood NL. Immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine devices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6:CD001777. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001777.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart GS, Grimes DA. Social desirability bias in family planning studies: a neglected problem. Contraception. 2009;80:108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper C, Thompson K, Waxman NJ, Speidel J. Provision of long-acting reversible contraception at US abortion facilities and barriers to immediate postabortion insertion (abstract only) Contraception. 2009;80:197–98. [Google Scholar]