SUMMARY

Lineage mapping has identified both proliferative and quiescent intestinal stem cells, but the molecular circuitry controlling stem cell quiescence is incompletely understood. By lineage mapping, we show Lrig1, a pan-ErbB inhibitor, marks predominately non-cycling, long-lived stem cells located at the crypt base that, upon injury, proliferate and divide to replenish damaged crypts. Transcriptome profiling of Lrig1+ colonic stem cells differs markedly from highly proliferative, Lgr5+ colonic stem cells; genes up-regulated in the Lrig1+ population include those involved in cell cycle repression and response to oxidative damage. Loss of Apc in Lrig1+ cells leads to intestinal adenomas and genetic ablation of Lrig1 results in heightened ErbB1-3 expression and duodenal adenomas. These results shed light on the relationship between proliferative and quiescent intestinal stem cells, and support a model in which intestinal stem cell quiescence is maintained by calibrated ErbB signaling with loss of a negative regulator predisposing to neoplasia.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanisms that regulate homeostasis in the highly dynamic, continuously self-renewing small and large (colonic) intestinal epithelia are not fully elucidated. In particular, there is considerable debate about the nature of stem and progenitor cells within these tissues. Based primarily upon radiation-response studies, intestinal stem cells (ISCs) were long thought to be relatively quiescent, capable of becoming more mitotically active to repopulate crypts in response to epithelial damage (Potten, 1998).

Long-term lineage tracing has identified Lgr5, Bmi1, mTert and Hopx (Barker et al., 2007; Montgomery et al., 2011; Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008; Takeda et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2011) as bona fide ISC markers. Bmi1+ and mTert+ cells reside at position four from the crypt base, are largely quiescent and exhibit a steep gradient of expression from the proximal to distal intestine. The finding that Lgr5 marks a distinctive, highly proliferative population of small intestinal and colonic SCs has challenged the existence of quiescent SCs. However, Tian et al. recently demonstrated that Bmi1+ cells give rise to Lgr5+ cells and can substitute for Lgr5+ cells when Lgr5+ cells are eliminated in the small intestine. These investigators noted the lack of Bmi1 expression in the colon and suggested another, yet undefined, SC population may be important when Lgr5+ cells are lost in the colon.

To identify and characterize novel colonic SC markers with known functions, we performed gene expression profiling of CD24-purified mouse colonic epithelial progenitor cells (Akashi et al., 1994; Gracz et al., 2010) and identified the Leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domains 1 (Lrig1) gene. Lrig1 is a transmembrane protein that acts as an inducible, negative feedback inhibitor of ErbB signaling (Laederich et al., 2004). Lrig1 has been suggested to mark a multipotent and quiescent SC population in mammalian epidermis, although lineage tracing was not performed (Jensen et al., 2009; Jensen and Watt, 2006). Lrig1 null mice develop psoriasis, a hyperproliferative disorder of the skin (Suzuki et al., 2002), suggesting that Lrig1 is important for the maintenance of tissues that undergo continuous self-renewal and may serve to suppress growth in those tissues. In addition, LRIG1 mRNA and protein expression are down-regulated in a number of solid tumors (Ljuslinder et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2008;Thomasson et al., 2003; Ye et al., 2009).

In this study, we show that Lrig1 marks a subset of ISCs that are relatively quiescent under homeostatic conditions, but are mobilized upon tissue damage to repopulate the colonic crypt. Whole transcriptome analysis of Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ colonic epithelial cells reveals significant differences in the molecular programs of the two cell populations. We also show that loss of Apc in Lrig1+ cells results in multiple intestinal adenomas with the largest tumors in the distal colon. In addition, we demonstrate that Lrig1 null mice develop duodenal adenomas, providing the first in vivo evidence that the ErbB negative regulator, Lrig1, functions as a tumor suppressor. Taken together, these results underscore the importance of calibrated ErbB signaling in the ISC niche and the neoplastic consequences of perturbing this regulation.

RESULTS

Lineage tracing reveals that Lrig1 marks ISCs

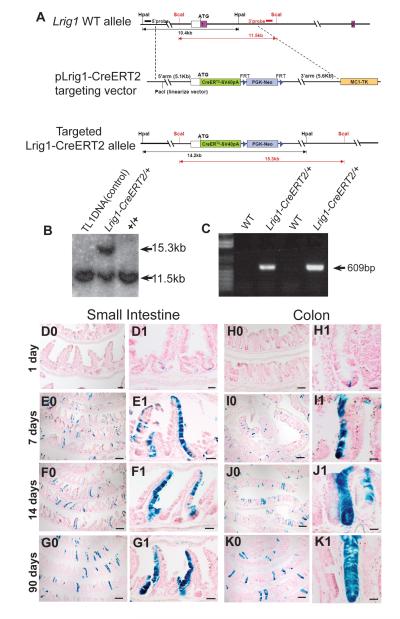

Based on Lrig1 expression in CD24-sorted mouse colonocytes (data not shown) and immunohistochemical detection in quiescent SCs in the epidermis (Jensen et al., 2009), we sought to determine if Lrig1 marked ISCs. We generated an Lrig1 knock-in allele, into which a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase (CreERT2) (Feil et al., 1997) was targeted by homologous recombination to the translational start site of the endogenous Lrig1 locus (Lrig1-CreERT2; Figure 1A-C; Table S1-S2). Lineage tracing was performed by intercrossing Lrig1-CreERT2 and R26RLacZ mice (Soriano, 1999).

Figure 1. Lineage tracing in the small intestine and colon confirms Lrig1 marks SCs.

(A-C) Generation of Lrig1-CreERT2/+ mice. (A) Schematic representation of the Lrig1-CreERT2 targeting vector. A tamoxifen-inducible Cre (CreERT2) was targeted into the translational initiation site of the endogenous Lrig1 locus. Southern blot analysis of embryonic SCs with 3′, 5′ and internal neo probes confirmed the correct integration at a frequency of 8.7% (B and data not shown). Chimeras were mated with FlpE mice to achieve germ-line transmission and neo cassette removal. The resulting heterozygous and homozygous mice were viable and fertile. (C) Lrig1-CreERT2 animals were genotyped by specific Lrig1-CreERT2 PCR. (D0-G0) Low-power view of Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ lineage-labeled small intestine at different time points following a single i.p. injection of 2mg tamoxifen. (D1-G1) Representative sections of high-power view of β-gal+ small intestine. (H0-K0) Low-power view of Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ lineage-labeled colon at different time points following a single i.p. injection of 2mg tamoxifen. (H1-K1) Representative sections of high-power view of β-gal+ colonic crypts. Scale bars represent 100μm in D0 and H0; 200μm in E0-G0 and I0-K0; 50μm in D1-G1 and 25μm in H1-K1. See also Figure S1 and Table S1-S2.

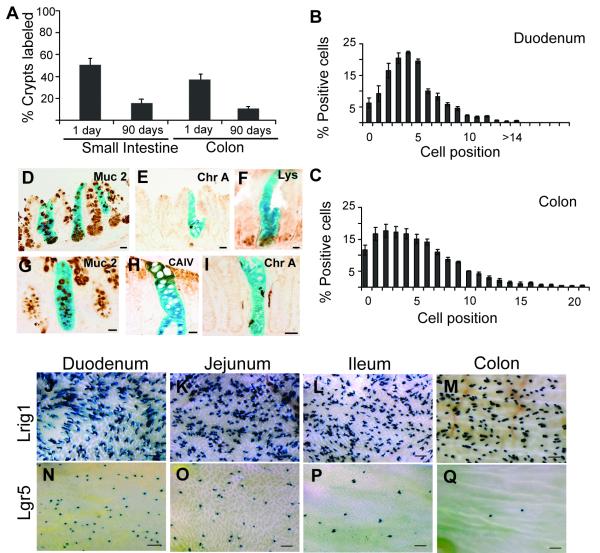

Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ (hereafter Lrig1 reporter) mice received one intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 2mg tamoxifen. Small intestine and colon were stained in whole-mount for β-galactosidase (gal) activity over time (Figure 1D0-K1) with β-gal reporter reflecting Lrig1 mRNA expression. One day after tamoxifen induction, over 50% of small intestinal and 40% of colonic crypts were labeled (Figure 2A). Most labeled crypts contained one or two β-gal+ cells, virtually all of which were at the bottom one-third of crypts (Figure 1D1, H1, 2B-C and high-power images in Figure S1A-B). However, some cells were located further up in the crypts, as indicated in Figure 2B-C. Seven days after induction, gal staining was more widespread (Figure 1E0-E1 compared to D0-D1, and I0-I1 compared to H0-H1) as initially tagged cells proliferated and generated gal+ progeny. At 14 days post-injection, both fully and partially labeled crypts and villi were observed (Figure 1F0-F1 and J0-J1). At 90 days, 18% of small intestinal and 10% of colonic crypts were entirely lineage-labeled (Figures 1G0-G1, K0-K1, 2A and S1C) and contained the differentiated cell lineages of the small intestine and colon (Figure 2D-I). Labeled crypts remained entirely β-gal+ and accounted for up to 20% of total crypts up to 6.5 months (data not shown), providing definitive evidence that Lrig1 marks intestinal SCs. Lrig1 lineage tracing also detected short-(24 hours) and long-term (two months) labeled cells in the gastric epithelium and skin (Figure S1D-E); studies are underway to characterize these progenitor cell populations.

Figure 2. β-gal labels Lrig1+ cells in the SC niche, persists in the long-term and labeling differs in Lgr5-reporter mice.

(A) One day after tamoxifen induction, 50% of small intestinal crypts and 40% of colonic crypts are labeled. At 90 days, the number of labeled crypts decreases to 18% in the small intestine and 10% in the colon. (B-C) Frequency of β-gal+ cells at different positions relative to the small intestinal (B) and colonic (C) crypt base one day after tamoxifen administration. (D-I) Co-staining with various differentiation markers to confirm multipotency of progeny of β-gal+ cells: Mucin2 (Muc 2) marks goblet cells (D,G); Chromogranin-A (Chr A) marks enteroendocrine cells (E,I); Lysozyme (Lys) marks Paneth cells (F); and Carbonic Anhydrase IV (CAIV) marks enterocytes (H). (J-M) Whole-mount view of Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ and (N-Q) Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2;R26RLacZ/+ lineage-labeled intestines. Error bars represent s.e.m. Scale bars in D-I represent 25μm and J-Q represent 500μm. See also Figure S2.

We next compared lineage tracing of Lrig1 reporter mice to Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2;R26RLacZ/+ mice. Using the induction scheme published for these Lgr5 reporter mice (Barker et al., 2007), there was a markedly greater number of lineage-labeled crypts along the length of the intestine at three months in Lrig1 reporter mice (Figure 2J-Q, S2) compared to the Lgr5 reporter mice, demonstrating a clear difference in the ability of these Cre drivers to efficiently label intestinal epithelial SCs. It is important to note lineage tracing studies indicate where the targeted gene is transcribed and do not necessarily reflect protein production.

Lrig1 marks a distinct population of intestinal stem cells

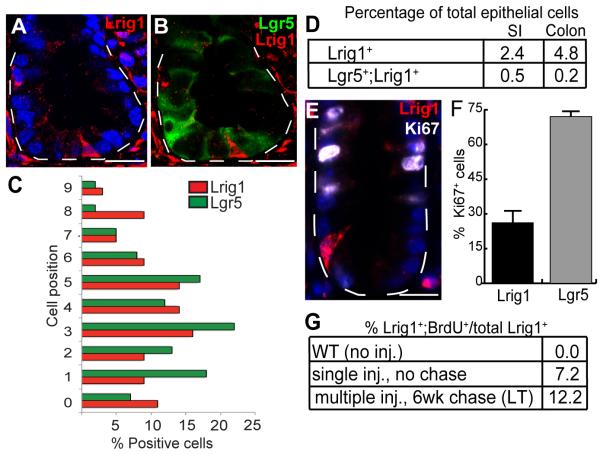

To examine protein expression directly, we generated an antibody to the Lrig1 ectodomain, validated specificity in Lrig1−/− (Suzuki et al., 2002) colonic tissue (Figure S3A) and performed immunostaining in Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 and wild-type mice. We compared Lrig1 and Lgr5 expression, as Lgr5 is an established SC marker in mouse colon. Since antibodies do not exist to examine endogenous Lgr5, we relied on EGFP fluorescence as a surrogate marker of Lgr5 expression. In normal mouse colon, we observed Lrig1 protein reproducibly decorates one to three cells at the crypt base (Figure 3A-B and Figure S3B) and occasionally cells higher up the crypt (Figure 3C). By immunofluorescent confocal analysis of crypt cross-sections, as well as 3-D imaging of isolated crypts, crypts containing Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ cells were observed less frequently than crypts containing cells expressing either marker alone. Nevertheless, when both populations were observed in the same crypt, colocalization of the two markers rarely occurred in the same cell (Figure 3B and Figure S4A-C).

Figure 3. Expression patterns of Lrig1 and Lgr5 in adult mouse colon by immunofluorescence and FACS.

(A-B) Immunofluorescent detection and confocal microscopy of cross-sections in Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mouse colon detected a subset of Lrig1+ cells (red) present at the crypt base, distinct from Lgr5+ cells (green). (C) Relative position of Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ populations by immunofluorescence for Lrig1 and direct EGFP fluorescence of the Lgr5 reporter. (D) FACS analysis of Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mouse intestinal epithelial cells (n=9); Lrig1 was detected in 2.4% of total enterocytes and 4.8% of total colonocytes. Using EGFPhi as a marker of Lgr5 expression, 0.5% of total enterocytes and 0.2% of total colonocytes were Lgr5+;Lrig1+. (E) A representative colonic crypt stained for Lrig1 (red) and Ki67 (white). (F) Twenty-five percent of Lrig1+ cells also stained with Ki67, whereas 75% of the Lgr5+ population also stained with Ki67. (G) BrdU incorporation, measured in Lrig1 mouse colonocytes by FACS. Lrig1+;BrdU+ cells were not detected in uninjected mice; 7% of Lrig1+ colonocytes co-expressed BrdU 2 hours after injection (n=3). Mice injected daily for five days and examined six weeks later, had 12% Lrig1+;BrdU+ colonocytes (n=3). “LT” indicates long-term, label-retaining experiment. Scale bars represent 25μm (A-B, E). Error bars represent s.e.m. See also Figure S3-S4.

To quantify the number of Lrig1+ cells in adult mouse colon, we performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of single epithelial cell suspensions generated from isolated Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 colonic crypts. We found 2.4% (small intestine) and 4.8% (colon) of total cells expressed Lrig1 alone (Figure 3D), consistent with reports for the clonogenic population predicted to be present within the colon (Cai et al., 1997; Hendry et al., 1992; Potten, 1998). Using EGFP as an indicator of Lgr5 expression, 0.5% (small intestine) and 0.2% (colon) of total cells expressed both Lgr5 and Lrig1 (Figure 3D), reflecting how infrequently this double-positive population was observed in tissue sections (Figure S4A-C). This, however, may be an underestimate, given that EGFP expression may be present less frequently than endogenous Lgr5 (Escobar et al., 2011). Finally, we examined the position of Lrig1+ cells in Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice and found both Lgr5+ and Lrig1+ cells were located primarily at positions 1-5 (Figure 3C).

Lrig1+ cells are label retaining and slowly cycling

We next examined the proliferative state of Lrig1+ cells. As previously reported (Barker et al., 2007), Lgr5 is expressed in elongated, crypt base columnar cells, frequently positive for the proliferative marker Ki67 (Figure S4D). Lrig1+ cells had a lower proliferative index (25% Ki67 positive; Figure 3E-F and Figure S4E) than Lgr5+ cells (75% Ki67 positive). To further explore the quiescence of Lrig1+ cells, we performed both short- and long-term Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling analyses. First, wild-type mice were injected daily for five days with BrdU (allowing for maximal BrdU incorporation, as mouse intestinal epithelium turns over once per week) and subsequently maintained for six weeks without injection. To quantitatively measure label retention, Lrig1+/BrdU+ colonic epithelia were subjected to FACS. Approximately 12% of Lrig1+ cells were BrdU+ (Figure 3G). If measured after five days of BrdU injection, but before the six-week chase, nearly 20% of Lrig1+ cells were BrdU+ (data not shown). In separate experiments, wild-type mice were injected with BrdU and colonic epithelia analyzed two hours later by FACS for Lrig1 and BrdU positivity. Approximately 7% of Lrig1+ cells were BrdU+, consistent with the minority population of Lrig1+ cells being also Ki67+ (Figure 3G) at a snapshot in time. Our Ki67 and BrdU analyses reveal the majority of Lrig1+ cells are infrequently cycling, although they appear more proliferative than Bmi1 and mTert populations (Montgomery et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2011).

Long-lived, individual Lrig1+ cells repopulate damaged crypts

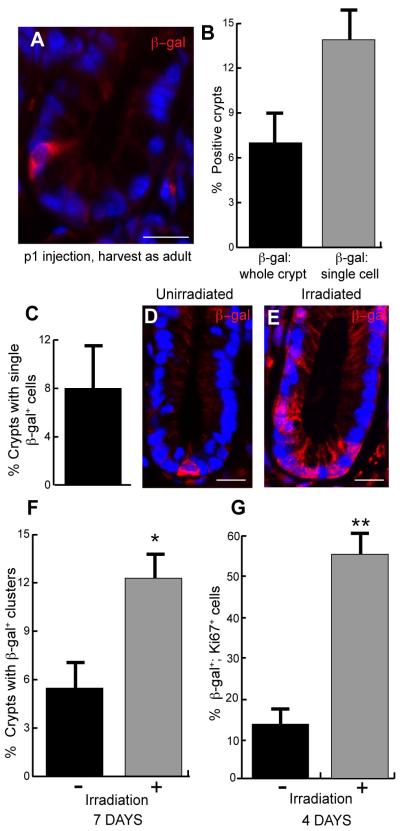

A notable finding from our long-term lineage tracing analysis in adult Lrig1 reporter mice was that 8% of total colonic crypts harbored single gal+ cells near the crypt base (Figure 4A,D and Figure S3C). After tamoxifen injection of Lrig1 reporter mice at birth and examination of colons six weeks later, the number of crypts with single-positive cells increased to 15% (Figure 4A-B). These results indicate that lineage tracing in the developing mouse differs from the adult; however, both approaches yield single-labeled cell populations. In the adult, these long-lived, singly labeled cells did not express Chromogranin-A (Figure S4F-H), which marks enteroendocrine cells (long-lived, differentiated cells that can be present at the crypt base).

Figure 4. Lrig1+ cells can be traced from birth and proliferate in response to irradiation damage.

(A) Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R262RLacZ/+ mice injected with tamoxifen at postnatal day one and sacrificed six weeks later, harbored single, β-gal+ label-retaining colonocytes at the crypt base. (B) Examination of β-gal in the p1 injected animals revealed 7% colonic crypts (n=2; 400 crypts/animal) were entirely β-gal+, while nearly 13% contained single, β-gal+ label-retaining colonocytes at the crypt base. (C) In long-term, tamoxifen-induced Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R262RLacZ/+ mice, 8% of β-gal+ cells were single cells at the base of the colonic crypt. (D-E) One week after irradiation damage, many colonic crypts contained β-gal+ cells in clusters. (F) Clusters of β-gal+ cells increased in animals subjected to irradiation. In control (unirradiated) animals, 5% of colonic crypts contained β-gal+ clusters; this number increased to 12% in irradiated animals. (G) Examination of β-gal+ cells in control and irradiated Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R262R-LacZ animals revealed that 14% of β-gal+ cells stained with the proliferative marker Ki67 in control animals, whereas this number increased to 55% in irradiated animals. All scale bars represent 25μm. Error bars represent s.e.m. See also Figure S3-S4.

To test if single gal+ cells were quiescent SCs, we performed irradiation injury with the expectation that they would divide and produce progeny to repair the damaged tissue. We subjected long-term (six month) labeled Lrig1 reporter mice to a single dose (8Gy) of X-ray irradiation. In unirradiated, long-term labeled control animals, β-gal labeling was observed in single cells at the crypt base (Figure 4D) and, as expected, in fully labeled crypts (Figure S3D). No β-gal staining was observed in irradiated, wild-type animals without the Lrig1 reporter (Figure S3E). Four days after irradiation of Lrig1 reporter mice, 55% of single β-gal+ cells stained with Ki67 (n=3; Figure 4G; p=0.006), while in unirradiated mice, only 14% of single β-gal+ cells expressed Ki67. One week after irradiation, 12% of colonic crypts contained β-gal+ clusters (n=3), while in unirradiated animals, only 5% of crypts contained clusters (n=2; Figure 4E-F). This shift represented a significant increase in irradiated animals (Figure 4F, p=0.04), likely owing to increased proliferation. The proliferative increase is expected based on published reports of proliferative indices of intestinal progenitor cells during homeostasis and following irradiation injury (Potten, 1998; Potten and Grant, 1998). Based on these results, we conclude Lrig1+ cells exhibit proliferative heterogeneity (Simons and Clevers, 2011), wherein a predominately quiescent progenitor population can proliferate and give rise to daughter cells under the appropriate stimulus.

Global transcriptional analysis of Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ stem cells

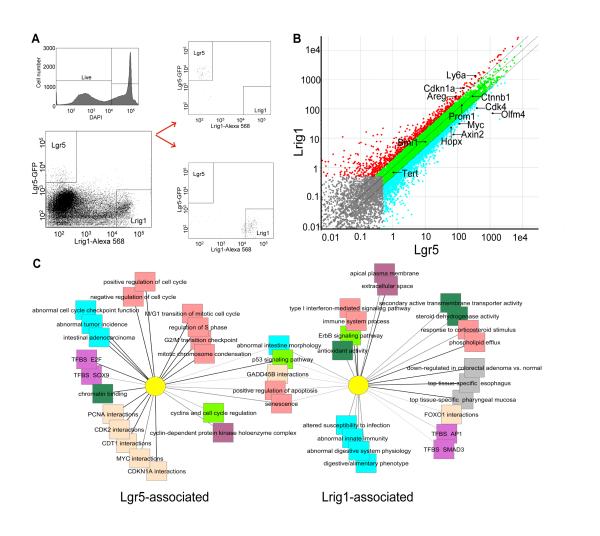

By genetic and biochemical analyses (Figures 1-4), Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ cells appear to be different, yet related, cell populations. To better appreciate similarities and differences in the two populations, we isolated Lgr5-EGFPhi and Lrig1+ cells by FACS from six- to eight-week-old Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 colonic crypts for whole transcriptome sequencing (Figure 5A-B). The transcriptome sequencing identified ~21,000 total genes, of which ~2,500 were significantly differentially regulated (Table S3). Comparing the populations at a transcriptional level revealed similarities related to epithelial biology and stemness, as well as a number of key differences related to cell cycle and oxidative stress (Figure 5C and Table S3). Both populations expressed similar levels of genes associated with ISCs such as mTert, Prominin1 and Bmi1 (not reported to be expressed robustly in the colon; Figure 5B and S5A), and classic intestinal epithelial cell-associated genes, such as β-catenin, E-cadherin, Keratin 8, Epithelial cell adhesion molecule, Occludin, and Claudins 2 and 7 (Figure 5B and Figure S5A).

Figure 5. RNA-Seq analysis of Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ cells.

(A). Gating strategies for FACS analysis of Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mouse colonic epithelial cells (n=5) used to isolate Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ populations (Lrig1-Alexa568 and Lgr5-EGFPhi, respectively) for RNA-Seq analysis. (B) Scatter plot depicting representative gene expression profiles of Lrig1+ (Y-axis) and Lgr5+ (X-axis) cells. Fragments Per Kilobase Per Million reads (FPKM) analysis was conducted and ~21,000 genes are shown in the plot. Transcripts detected below 0.5 FPKM (little biological significance) are shown in gray. Red indicates genes significantly expressed in Lrig1+ cells, compared to Lgr5+ cells, while blue indicates genes that are significantly expressed in Lgr5+, compared to Lrig1+ cells. Transcripts shared by both Lgr5+ and Lrig1+ cells are shown in green. Approximately 2,500 significantly differentially regulated genes are shown (red and blue). Some of genes discussed in Results are annotated in the figure. Genes plotted between 100 and 1000 FPKM are highly expressed. (C) Abstract network depicting Lgr5- and Lrig1-associated genes in each list that share structural or functional associations, including gene ontology properties, human disease and mouse knockout phenotype associations, shared regulatory elements and protein interactions. Significant gene feature associations that are unique or shared between the two cell compartment gene lists are shown. “TFBS” stands for a multispecies conserved transcription factor binding site. See also Figure S5 and Table S3.

Notable differences between the two populations were also observed. Lgr5 and Olfactomedin4 (Olfm4), a surrogate marker for Lgr5+ cells (van der Flier et al., 2009), were under-represented in Lrig1+ cells but highly expressed in Lgr5+ cells (Figure 5B and S5A), validating that the EGFPhi sorted cell population were true Lgr5+ cells, as reported (Barker et al., 2007). Consistent with the differing cell cycle status of the two populations, a number of cell cycle-promoting genes (PCNA, Axin2, Myc, Cyclin-dependent kinase 4) were significantly enriched in Lgr5+ cells (Figure 5B and S5A). Biological pathway analysis of Lgr5+ cells revealed that one of the predominant programs in Lgr5+ cells is cell cycle promotion (Figure 5C). Of note, a recently discovered marker of ISCs, Hopx (Takeda et al., 2011), is expressed nearly two-fold greater in Lgr5-EGFPhi cells than in Lrig1+ cells. In contrast, Lrig1+ cells highly expressed Ly6a, or Sca-1, a hematopoietic SC marker (Spangrude et al., 1988), as well as the Egfr ligand, amphiregulin (Areg; Figure 5B-C and S5A). Importantly, the cell cycle inhibitor Cdkn1a (p21) was also highly expressed in Lrig1+ cells (Figure 5B and Figure S5A). Finally, Lrig1+ cells co-expressed Ca2, IL1rn, Apoe, Ccl5, Ccl8, Cd38 and Tst, a subset of genes up-regulated when comparing quiescent to dividing CD34+ cells (Graham et al., 2007) (Figure 5C; Table S3). The lack of association with cell cycle-promoting genes and the significant expression of Cdkn1a are consistent with our findings that Lrig1 marks a SC population that is less frequently cycling, or is in the process of downregulating the cell cycle.

Furthermore, general pathway analysis revealed Lrig1+ cells expressed genes involved in protecting cells from oxidative damage, as well as a FoxO1 interaction network, which contains important mediators of SC oxidative stress responses (Tothova et al., 2007). Lgr5 is expressed over 20-fold higher in Lgr5+ cells than Lrig1+ cells, and Lrig1 is expressed at modestly higher levels in Lgr5+ cells (Figure S5A). A subset of genes was validated by qRT-PCR. These results largely correlated to the RNA-Seq data; however, we observed discordant results for lowly expressed genes such as mTert (Figure S5A-B). In summary, our whole transcriptome analysis data suggest Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ colonic SCs are largely distinct in their mRNA expression profiles, and harbor specific gene expression differences related to cell cycle regulation and oxidative stress responses, possibly mediated through FoxO signaling.

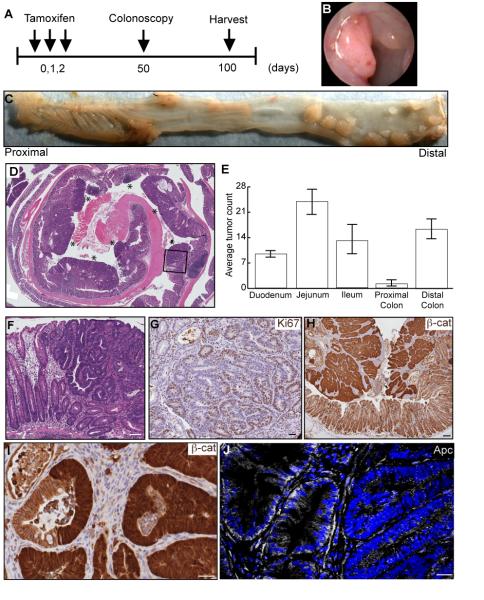

Apc loss in Lrig1+ cells results in dysplastic, histologically advanced intestinal adenomas

In the highly dynamic and rapidly renewing intestinal epithelium, it is thought that SCs, but not transit-amplifying and differentiated cells, have a sufficient lifespan to acquire the number of mutations required for cancer development (Clarke et al., 2006). We utilized Lrig1-CreERT2/+;Apcfl/+ mice to examine if an initiating event in Lrig1+ cells would result in “full-blown” tumors (Barker et al., 2009). Upon administration of tamoxifen, one Apc allele was removed in Lrig1+ cells (Shibata et al., 1997) (Figure 6A), and tumors arose with stochastic loss of the second Apc allele (Figure 6J and Figure S6A). We observed colonic tumors at day 50 by colonoscopy (Figure 6B); at the time of sacrifice (100 days; n=17), there were multiple, distal colonic tumors with little to no tumor burden in the proximal colon (Figure 6C-E). The tumor phenotype was 100% penetrant and the distribution and multiplicity of tumors from seven mice are shown in Figure 6E, with the greatest number of tumors observed in the jejunum. The largest tumors were found in the distal colon, many greater than 2mm in size with areas of high-grade dysplasia (Figure 6D,F). Immunohistochemical examination of colonic tumors revealed they were highly proliferative (Ki67 staining in Figure 6G) and, consistent with loss of Apc (Figure 6J and Figure S6A), harbored large areas of cytosolic and nuclear β-catenin (Figure 6H-I). These tumors did not exhibit loss of E-cadherin or show invasive properties (data not shown). Examination of tumors from Lrig1-CreERT2/+;Apcfl/+;R26RLacZ mice revealed heterogeneous β-gal staining (Figure S6D), indicating that these tumors may be polyclonal (Thliveris et al., 2011). No tumors were detected in vehicle-injected, control mice (data not shown).

Figure 6. Lrig1-CreERT2/+;Apcflox/+ mice develop colonic tumors.

(A) Schematic depiction of experimental design. Mice were injected with tamoxifen daily for three days, monitored by colonoscopy starting at day 50 and sacrificed 100 days post-tamoxifen induction. (B-C) Examination of mice three months post-induction revealed the mice developed distal colonic tumors (shown by colonoscopy in B and by whole mount in C). (D) H&E staining of a tissue cross-section from a representative colon. Individual tumors are indicated by the asterisks. (E) Distribution and multiplicity of tumors from seven mice with the greatest number of adenomas formed in the jejunum. (F) High-grade dysplasia was present within a large tumor (black box in D). (G-I) Immunohistochemical examination of colonic tumors for Ki67 expression (brown in G), nuclear and cytosolic β-catenin (brown in H), and high-power image of a gland that contains both cytosolic- and membrane-associated β-catenin (I). (J) Immunofluorescent examination of colonic tumors for Apc expression (white); Apc expression is heterogeneous. Scale bars represent 50μm in F, 25μm in G, I and J and 75μm in H. Error bars represent s.e.m. See also Figure S6.

Under identical experimental conditions performed concurrently, we observed no intestinal tumors in Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2;Apcfl/+ mice (Figure S6B-C), as reported previously (Barker et al., 2009). These results indicate Lrig1+ cells are long-lived and capable of forming histologically advanced adenomas following loss of Apc and also provide additional evidence that Lrig1 marks ISCs.

Ablation of Lrig1 results in highly penetrant duodenal adenomas

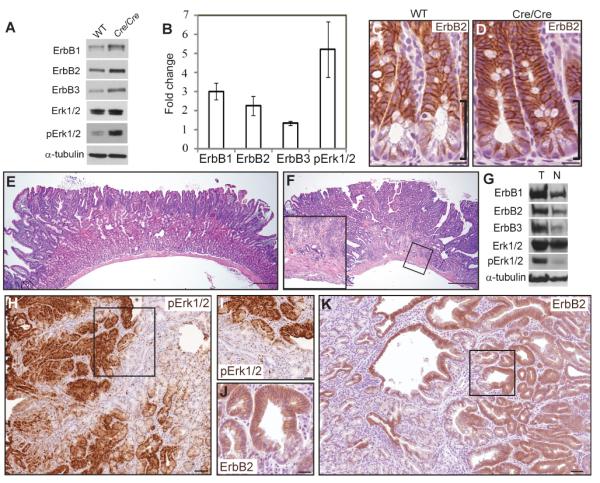

Lrig1 is a pan-ErbB negative regulator, prompting us to examine whether there was a phenotypic consequence in the intestine of mice in which both Lrig1 alleles were disrupted (homozygous for Lrig1-CreERT2). As expected, full-length Lrig1 protein was lost in the small intestine and colon of Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice (Figure S7A). In our examination of Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2; Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice that lack Lrig1 but contain the Lgr5-EGFP reporter, the number of Lgr5-EGFP+ crypts more than doubled, compared to mice with one or both copies of Lrig1 (Figure S7D); we also observed an increase in Lgr5 transcript expression by qRT-PCR (Figure S7E). These results, modeled in Supplemental Figure 7H, support the notion that loss of Lrig1 protein in the SC niche may affect the Lgr5+ population.

In addition, consistent with Lrig1 negative regulation of ErbB receptors, we detected a significant increase in ErbB1-3 protein levels and phosphorylated Erk1/2 (pErk1/2) by western blot analysis of small intestinal crypt lysates from Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice compared to wild-type mice (Figure 7A-B). Of note, Egfr was the most upregulated of the ErbB receptors. We also observed increased ErbB2 immunoreactivity in intestinal crypt epithelia of Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice (Figure 7C-D).

Figure 7. Homozygous Lrig1-CreERT2 mice exhibit up-regulation of ErbB1-3 and develop duodenal adenomas and superficially invasive carcinomas.

(A) Representative western blot showing increased ErbB1-3 and pErk1/2 levels in crypt epithelium isolated from small intestine of Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 (Cre/Cre) mice compared to wild-type (WT) mice. (B) Quantification of protein expression levels shown in (A). (C-D) Immunohistochemical examination of ErbB2 (brown) in intestinal crypts from WT (C) and Cre/Cre (D) mice. Black brackets indicate differential staining at the crypt base. (E) Representative H&E staining of an adenoma from a five-month-old Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mouse. Tumors exhibited low-grade dysplasia and a marked plaque-like expansion of Brunner’s glands (n=14). (F) One tumor exhibiting histological progression: areas of cribiform architecture and loss of cellular polarity and focal extension of neoplastic glands into deeper layers of the bowel wall, suggestive of early invasion (inset). (G) Representative western blot showing increased ErbB1-3 and pErk1/2 levels in tumor (T) compared to gross normal duodenum (N) of Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice. (H-I) Immunohistochemical examination of pErk1/2 (brown in H) in tumors from Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice; boxed region magnified in I. (J-K) Immunohistochemical examination of ErbB2 (brown in K) in tumors from Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice; boxed region magnified in J. Scale bars represent 25μm in C, D, I and J, represent 100μm in E and F and 75μm in (H and K). Error bars represent s.e.m. See also Figure S7 and Table S4.

Notably, at five to six months of age, 14/16 (88%) Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice developed duodenal tumors. Histologically, the tumors were low-grade adenomas with elongated, crowded nuclei and increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. A distinctive feature was a marked plaque-like expansion of Brunner’s glands underlying the tumors (Figure 7E). The tumors also expressed higher levels of ErbB1-3 and pErk1/2 protein (Figure 7G; quantified in Figure S7B) by western blot, and higher levels of pErk1/2 and ErbB2 by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 7H-K) compared to grossly normal intestinal epithelium. By 13 to 14 months of age, 17/19 mice had duodenal adenomas that were larger and histologically more advanced than those at six months. For example, in one mouse examined at 13 months of age, the tumor displayed areas of cribriform architecture with loss of cellular polarity, indicative of high-grade dysplasia, and focal extension of neoplastic glands into deeper layers of the bowel wall, suggestive of early invasion (Figure 7F and inset). Analysis indicated that these tumors harbored intact Apc (Figure S7C) and did not express nuclear β-catenin (data not shown), suggesting they arose in a manner independent of dysregulated canonical Wnt signaling. Taken together, these data are consistent with a model in which Lrig1 antagonizes ErbB signaling in the intestinal epithelium to maintain epithelial homeostasis and disruption of this negative feedback loop can lead to tumor formation.

DISCUSSION

We have identified that the ErbB negative regulator, Lrig1, marks a predominantly quiescent SC population and serves a functional role in the maintenance of small intestinal and colonic epithelial homeostasis. Mice lacking Lrig1 develop duodenal tumors, indicating it functions as a tumor suppressor. Our data contribute to the debate on the complex heterogeneity of ISC populations and shed light on the relationship between normal ISCs and cells that give rise to neoplasms in this tissue.

Lrig1 marks a distinct class of intestinal stem cells

Our lineage tracing studies establish that Lrig1 marks both small intestinal and colonic SCs and several pieces of evidence suggest these SCs are distinct from those expressing Lgr5. First, comparison of Lgr5-EGFP and Lrig1 protein indicates they are rarely co-expressed in colonocytes (Figures 3 and S4). Second, Lgr5-EGFP+ cells, but not Lrig1+ cells, are frequently positive for Ki67 (Figure S4). Moreover, the distinct nature of Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ SCs is supported by transcriptome profiling. Lgr5+ cells express many genes associated with cell cycle promotion, while Lrig1+ cells do not, but rather express genes associated with immune regulation and oxidative stress. These include genes involved in protecting cells from oxidative damage, as well as a FoxO1 interaction network, which includes mediators of oxidative stress responses in other SC systems (Storz, 2011; Tothova et al., 2007). Notably, Cdkna1, which is significantly up-regulated in the Lrig1+ cells, is a target of FoxO signaling (Seoane et al., 2004), suggesting its cell cycle repressive properties are linked to the damage response. Interestingly, it has been shown recently that FoxO factors are required for maintenance of pluripotency of human embryonic SCs (Zhang et al., 2011). While this hypothesis-generating RNA-Seq analysis offers many leads to pursue, it suggests Lrig1+ cells repress cell cycle progression and may play a significant role in oxidative damage responses.

Placing Lrig1+ stem cells within a continuum of intestinal stem cells

The RNA-Seq data affords an opportunity to compare the relative expression of other SC markers within the Lrig1+ and Lgr5+ populations. mTert, Bmi1 and Prominin1 are expressed equivalently in the two populations. Hopx, recently shown to be a SC marker in the small intestine, is two-fold higher in Lgr5+ colonocytes, consistent with interconversion of Hopx+ and Lgr5+ small intestinal SCs (Takeda et al., 2011). Of interest, the hematopoietic SC marker Ly6a (Sca-1) (Spangrude et al., 1988) is highly expressed, specifically in Lrig1+ SCs. The putative SC markers, Dclk1 and Musashi-1, were expressed at insignificant levels in both populations under these experimental conditions. Keeping in mind that the data from our whole transcriptome analysis are from an isolated snapshot in time, and thus must be carefully interpreted, our results, as well as a recent report examining co-expression of SC markers in the small intestine (Itzkovitz et al., 2011), support the notion that ISC populations are heterogeneous, yet inter-related. We posit that an individual colonic SC population may have a predominate program (for example, cell cycle promotion or oxidative stress response), but may be capable of transitioning to or from another state. Thus, expression of individual SC markers may reflect cell state, making each population distinct from others at a given point in time. In this regard, we show that Lgr5 expression and the number of Lgr5-EGFP+ crypts significantly increases in Lgr5-EGFP reporter mice that lack Lrig1 compared to control mice (Figure S7D). It will be of interest to determine whether Lrig1+ SCs substitute for loss of Lgr5+ SCs in the colon of Lgr5DTR mice, as Bmi1+ SCs do in the small intestine (Tian et al., 2011). Ultimately what governs these states and regulates their transitions, during homeostasis and upon injury, represents a major challenge for ISC biologists.

Using the metrics of proliferation, cell position and the reported cell number(s) per crypt (Barker et al., 2007; Montgomery et al., 2011; Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008; Takeda et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2011), we envision that Lrig1+ SCs are downstream from the more quiescent Bmi1+ or mTert+ SCs, and subserve two roles in homeostasis: 1) to protect the niche from stress and 2) to give rise to transit-amplifying cells directly and/or to Lgr5 SCs, when needed, as modeled in Figure S7H. We believe the direct transition from an Lrig1+ SC to an Lgr5+ SC happens infrequently, as we rarely observe colocalization of Lrig1 and the Lgr5-EGFP reporter, and transcriptome analysis indicates the two populations have a large number of significantly differentially regulated pathways. Overall, our results, and data from others (Takeda et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2011), represent initial efforts to understand how modulation of individual ISC populations can directly affect the state of others. Going forward, development of reliable antibodies will facilitate systematic assessment of ISC populations and how they relate to one another during homeostasis and in disease states.

Lrig1 in human cancer

Lrig1 has a defined role in negative regulation of ErbB receptors, Met (Shattuck et al., 2007) and Ret (Ledda et al., 2008), to exert control over cell growth. Consistent with this, we show Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice develop duodenal adenomas by six months of age and these tumors histologically progress over time, providing the first in vivo evidence that Lrig1 acts as a tumor suppressor (Figure 7). In support of this, LRIG1 is mutated in a subset of colorectal cancers (CRCs) and glioblastomas (The Cancer Genome Atlas; see Experimental Procedures). Moreover, LRIG1 expression is down-regulated in a number of human tumors, including bladder, lung, renal, squamous cell, breast, brain and CRC (Hedman and Henriksson, 2007; Ljuslinder et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2008; Tanemura et al., 2005; Thomasson et al., 2003; Ye et al., 2009). It is important to note that transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of Lrig1 is likely to be complex. For example, Lrig1 is a candidate for regulation by the miR-17-92 host gene cluster (via TargetScan, PicTar and Molecular Signatures Database analyses; see Experimental Procedures) and the ectodomain alone can function independently of full-length protein to attenuate EGFR signaling (Goldoni et al., 2007). These potential mechanisms of regulation may result in differential detection of Lrig1. Consistent with this, we observed variable expression of LRIG1 in microarray profiling of 100 human CRCs using two probe sets that anneal to two different regions of LRIG1. One probe set is highly expressed, whereas the other is down-regulated or lost. Variable expression of other intestinal stem cell markers is also observed (Figure S7F and Table S4). Similar to this expression profiling data, we observe variable LRIG1 protein in human CRC; in some cases, it is completely lost while in others, it is strongly expressed at the membrane (Figure S7G). These observations suggest the tumor suppressor function of LRIG1 is lost in a subset of CRCs. Further support of a tumor suppressor role for Lrig1 in intestinal neoplasia comes from the recent observation that Lrig1 is the most frequently disrupted gene in a subset of adenomas that progress to carcinoma using a Villin-CreERT2;Kras Sleeping Beauty transposon system (Neal Copeland and Nancy Jenkins, personal communication).

In summary, we identify the pan-ErbB negative regulator, Lrig1, as a functional marker of largely quiescent ISCs and show that it functions as a tumor suppressor. We propose that Lrig1 contributes to calibrated ErbB signaling in the ISC niche under homeostatic conditions and that its loss predisposes to neoplasia.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice and Tamoxifen Injection Regimens

The generation of Lrig1<tm1.1(cre/ERT)Rjc> (Lrig1-CreERT2) mice is detailed in Figure 1 and the Extended Experimental Procedures. FlpE, R26RLacZ and Apcfl/+ mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Lrig1-CreERT2/+ mice were crossed to R26RLacZ mice, Apcfl/+ mice, or intercrossed within littermates. Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice (generously provided by Rune Toftgard and Hans Clevers) were used alone or crossed to R26RLacZ mice. Duodenum from Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 was processed between five and 13 months of age. Lrig1−/− intestinal tissue was generously provided by Colleen Sweeney and prepared for cryosectioning. For lineage labeling, six to eight-week-old Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ mice were injected (i.p.) once with 2mg tamoxifen (Sigma) in corn oil. Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26R-EYFP mice were injected similarly for three consecutive days. For developmental labeling, postnatal day one Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ pups were given a single injection of tamoxifen (33mg/kg i.p.) and analyzed as adults. Apcfl/+ were crossed to Lrig1-CreERT2/+ mice; resulting Lrig1-CreERT2/+;Apcfl/+ mice were injected once with 2mg tamoxifen, as above, for three days and monitored over time (0-100 days) for tumor formation by colonoscopy. Analysis for Apc loss of heterozygosity (LOH) details are provided in the Extended Experimental Procedures. For the injury study, adult Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ mice were subjected to 8Gy irradiation three months after a single injection of tamoxifen.

Tissue Preparation for Staining

Tissue preparation and subsequent staining for β-gal were performed as previously described (Li et al., 2004). After taking whole-mount pictures for β-gal, tissues were “swiss-rolled,” dehydrated, paraffin-embedded, sectioned (10μm) and counterstained with nuclear fast red (Vector Lab). For cryosectioning, the tissue was isolated en bloc, processed for subsequent frozen block preparation and sectioned (5μm)(Wong et al., 1998). For duodenal western blot analysis intestinal epithelial preparation was performed as previously described (Whitehead and Robinson, 2009). Full details are provided in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Antibodies and Staining Conditions

Immunostaining on frozen sections was performed as previously described (Davies et al., 2009). GFP expression was visualized using direct fluorescence. Primary antibody information for IHC: Mucin 2 (Santa Cruz, sc-15334, 1:100); Chromogranin-A (Abcam, Ab15160, 1:150); Carbonic Anhydrase IV (R & D, AF2414, 1:50); Lysozyme (MP Biomedicals, #11423, 1:100; pH6 citrate buffer antigen retrieval); ErbB2 (Abcam, Ab2428, 1:100), phospho-p42/44 Erk (Cell Signaling, 1:1000); β-catenin (Transduction lab, 1:1000); APC-M2 (Wang et al., 2009) (1:1000). Sequential staining of YFP and Chromogranin-A was performed by first detecting the YFP signal (anti-GFP, Novus NB600-308, rabbit, 1:4000) with the vector signal amplification kit (Vector labs, PK-6101), followed by further amplification using TSA-Cy3 system (Perkin Elmer NEL704A001KT), both according to manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were then neutralized with Tris-glucose EDTA (25mM Tris-HCl, 10mM EDTA, 50mM Glucose, pH 9.0) in the microwave for seven minutes, allowing for additional rabbit antibody detection. Sections were subsequently stained for Chromogranin-A and detected by Alexa-488 secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, A11034, 1:400). Cryosections were analyzed for β–gal-expressing cells by using a polyclonal antibody to β–gal (ICL Laboratories, 1:500) or to examine Lrig1 expression directly, frozen colon tissue sections were stained with a polyclonal antibody to Lrig1, made against a mouse N-terminal peptide KILSVDGSQLKSYC in collaboration with Covance, Denver PA (1:500). Ki67 was detected using a monoclonal antibody (Dako, 1:250). Fluorescent secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno Research Cy3, 1:500 and Cy5, 1:250) were used to detect the primary stains. For colorectal cancer staining, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned (10μm) and stained with the above-mentioned Lrig1 antibody (1:250).

Isolation of Intestinal Epithelium and FACS

Freshly dissected mouse intestine was prepared as described (Powell et al., 2011); isolated crypts were then collected by slow centrifugation. Crypts were resuspended in 3% pancreatin solution for 90 minutes (Whitehead et al., 1987), pipetted to single cells and then collected by slow centrifugation. For FACS, cells were resuspended in Hams F12 media with 1% FCS for Lrig1 staining with Lrig1 antibody (Covance) conjugated to an Alexa-568 fluorophore (1:250; Molecular Probes). Lgr5+ cells were isolated based on EGFPhi expression. DAPI (1:10,000; Sigma) was used as a viability marker. Lrig1+ and Lgr5-EGFP+ cells were isolated using a Becton Dickson FACSAria II using a 100μm nozzle. Subsequent staining for BrdU was performed using the APC BrdU Flow kit (BD Pharmingen) and BrdU+ cells were analyzed using a Becton Dickson LSR II. Cell doublets were eliminated on the basis of pulse width.

RNA-Seq Analysis

RNA-Seq was conducted using FACS-isolated cells processed with an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The transcriptional sequencing methods were performed essentially as described (Mortazavi et al., 2008), which is a modification of the standard Illumina methods (Bentley et al., 2008). Sequencing reactions were performed using the Illumina HiSeq (v3 chemistry). Full details, as well as gene set enrichment, feature, biological network analysis and qRT-PCR, are provided in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Database Analysis

Mutations in LRIG1 in cancer were analyzed by accessing The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset through the Broad Integrative Genomics Viewer-IGV http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/. Full details regarding the colorectal cancer heat map are provided in Extended Experimental Procedures and Table S4. MicroRNA target predictions for Lrig1 were performed using TargetScan, microRNA.org, PicTar and Molecular Signatures Database v3.0.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AEP, YW, YL, KMH, JLF and RJC designed, executed and analyzed data. AJ, JNH and EJP provided technical assistance. SEL conducted the RNA-Seq. ALM, MKW, NP, YG, YS, and BJA provided expert analysis. AEP and RJC assembled the manuscript. We thank Frank Revetta and Catherine Meador for technical assistance. This work was supported by NCI CA151566 to RJC and KMH, and CA46413, MMHCC U01CA084239 and GI SPORE P50CA095103 to RJC, T32GM008554 to EJP and T32CA119925 to AEP. The authors acknowledge the support of Vanderbilt’s CTSA and Transgenic Mouse/ES Cell, Cell Imaging, and Flow Cytometry Shared Resources. We thank the Peter Powell and Mary Catherine Mundell Coffey Memorial GI Cancer Fund for its generous support.

Footnotes

Accession Numbers Preprocessed probe intensity scores for the CRC microarray are available from the GEO database under accession number GSE5206.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Akashi T, Shirasawa T, Hirokawa K. Gene expression of CD24 core polypeptide molecule in normal rat tissues and human tumor cell lines. Virchows Arch. 1994;425:399–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00189578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ, Clevers H. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL, Bignell HR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai WB, Roberts SA, Potten CS. The number of clonogenic cells in crypts in three regions of murine large intestine. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1997;71:573–579. doi: 10.1080/095530097143905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH, Jones DL, Visvader J, Weissman IL, Wahl GM. Cancer stem cells--perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PS, Powell AE, Swain JR, Wong MH. Inflammation and proliferation act together to mediate intestinal cell fusion. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar M, Nicolas P, Sangar F, Laurent-Chabalier S, Clair P, Joubert D, Jay P, Legraverend C. Intestinal epithelial stem cells do not protect their genome by asymmetric chromosome segregation. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:258. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Wagner J, Metzger D, Chambon P. Regulation of Cre recombinase activity by mutated estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237:752–757. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldoni S, Iozzo RA, Kay P, Campbell S, McQuillan A, Agnew C, Zhu JX, Keene DR, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. A soluble ectodomain of LRIG1 inhibits cancer cell growth by attenuating basal and ligand-dependent EGFR activity. Oncogene. 2007;26:368–381. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracz AD, Ramalingam S, Magness ST. Sox9 expression marks a subset of CD24-expressing small intestine epithelial stem cells that form organoids in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G590–600. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00470.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham SM, Vass JK, Holyoake TL, Graham GJ. Transcriptional analysis of quiescent and proliferating CD34+ human hemopoietic cells from normal and chronic myeloid leukemia sources. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3111–3120. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman H, Henriksson R. LRIG inhibitors of growth factor signalling - double-edged swords in human cancer? Eur. J. Cancer. 2007;43:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry JH, Roberts SA, Potten CS. The clonogen content of murine intestinal crypts: dependence on radiation dose used in its determination. Radiat. Res. 1992;132:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzkovitz S, Lyubimova A, Blat IC, Maynard M, van Es J, Lees J, Jacks T, Clevers H, van Oudenaarden A. Single-molecule transcript counting of stem-cell markers in the mouse intestine. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;14:106–114. doi: 10.1038/ncb2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Collins CA, Nascimento E, Tan DW, Frye M, Itami S, Watt FM. Lrig1 expression defines a distinct multipotent stem cell population in mammalian epidermis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Watt FM. Single-cell expression profiling of human epidermal stem and transit-amplifying cells: Lrig1 is a regulator of stem cell quiescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:11958–11963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601886103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laederich MB, Funes-Duran M, Yen L, Ingalla E, Wu X, Carraway KL, 3rd, Sweeney C. The leucine-rich repeat protein LRIG1 is a negative regulator of ErbB family receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47050–47056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledda F, Bieraugel O, Fard SS, Vilar M, Paratcha G. Lrig1 is an endogenous inhibitor of Ret receptor tyrosine kinase activation, downstream signaling, and biological responses to GDNF. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:39–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2196-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang H, Choi SC, Litingtung Y, Chiang C. Sonic hedgehog signaling regulates Gli3 processing, mesenchymal proliferation, and differentiation during mouse lung organogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2004;270:214–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljuslinder I, Golovleva I, Palmqvist R, Oberg A, Stenling R, Jonsson Y, Hedman H, Henriksson R, Malmer B. LRIG1 expression in colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:1118–1122. doi: 10.1080/02841860701426823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JK, Shattuck DL, Ingalla EQ, Yen L, Borowsky AD, Young LJ, Cardiff RD, Carraway KL, 3rd, Sweeney C. Suppression of the negative regulator LRIG1 contributes to ErbB2 overexpression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8286–8294. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RK, Carlone DL, Richmond CA, Farilla L, Kranendonk ME, Henderson DE, Baffour-Awuah NY, Ambruzs DM, Fogli LK, Algra S, et al. Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013004108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten CS. Stem cells in gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Phil. Trans. R. S. London. 1998;353:821–830. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten CS, Grant HK. The relationship between ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis and stem cells in the small and large intestine. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78:993–1003. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AE, Anderson EC, Davies PS, Silk AD, Pelz C, Impey S, Wong MH. Fusion between Intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages in a cancer context results in nuclear reprogramming. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1497–1505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:915–920. doi: 10.1038/ng.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane J, Le HV, Shen L, Anderson SA, Massague J. Integration of Smad and forkhead pathways in the control of neuroepithelial and glioblastoma cell proliferation. Cell. 2004;117:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck DL, Miller JK, Laederich M, Funes M, Petersen H, Carraway KL, 3rd, Sweeney C. LRIG1 is a novel negative regulator of the Met receptor and opposes Met and Her2 synergy. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:1934–1946. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00757-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H, Toyama K, Shioya H, Ito M, Hirota M, Hasegawa S, Matsumoto H, Takano H, Akiyama T, Toyoshima K, et al. Rapid colorectal adenoma formation initiated by conditional targeting of the Apc gene. Science. 1997;278:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons BD, Clevers H. Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell. 2011;145:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz P. Forkhead homeobox type O transcription factors in the responses to oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;14:593–605. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Miura H, Tanemura A, Kobayashi K, Kondoh G, Sano S, Ozawa K, Inui S, Nakata A, Takagi T, et al. Targeted disruption of LIG-1 gene results in psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia. FEBS Letters. 2002;521:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Jain R, LeBoeuf MR, Wang Q, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science. 2011;334:1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanemura A, Nagasawa T, Inui S, Itami S. LRIG-1 provides a novel prognostic predictor in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: immunohistochemical analysis for 38 cases. Dermatol. Surg. 2005;31:423–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thliveris AT, Clipson L, White A, Waggoner J, Plesh L, Skinner BL, Zahm CD, Sullivan R, Dove WF, Newton MA, et al. Clonal structure of carcinogen-induced intestinal tumors in mice. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2011;4:916–923. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson M, Hedman H, Guo D, Ljungberg B, Henriksson R. LRIG1 and epidermal growth factor receptor in renal cell carcinoma: a quantitative RT-PCR and immunohistochemical analysis. Br. J. Cancer. 2003;89:1285–1289. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Biehs B, Warming S, Leong KG, Rangell L, Klein OD, de Sauvage FJ. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tothova Z, Kollipara R, Huntly BJ, Lee BH, Castrillon DH, Cullen DE, McDowell EP, Lazo-Kallanian S, Williams IR, Sears C, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier LG, van Gijn ME, Hatzis P, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, Guryev V, Oving I, et al. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell. 2009;136:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Azuma Y, Friedman DB, Coffey RJ, Neufeld KL. Novel association of APC with intermediate filaments identified using a new versatile APC antibody. BMC Cell Biology. 2009;10:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead RH, Brown A, Bhathal PS. A method for the isolation and culture of human colonic crypts in collagen gels. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. 1987;23:436–442. doi: 10.1007/BF02623860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead RH, Robinson PS. Establishment of conditionally immortalized epithelial cell lines from the intestinal tissue of adult normal and transgenic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G455–460. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90381.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MH, Rubinfeld B, Gordon JI. Effects of forced expression of an NH2-terminal truncated beta-catenin on mouse intestinal epithelial homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:765–777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Gao Q, Xu T, Zeng L, Ou Y, Mao F, Wang H, He Y, Wang B, Yang Z, et al. Upregulation of LRIG1 suppresses malignant glioma cell growth by attenuating EGFR activity. J. Neurooncol. 2009;94:183–194. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9836-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yalcin S, Lee DF, Yeh TY, Lee SM, Su J, Mungamuri SK, Rimmele P, Kennedy M, Sellers R, et al. FOXO1 is an essential regulator of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:1092–1099. doi: 10.1038/ncb2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.