Abstract

Women diagnosed with or at high risk for breast cancer increasingly choose prophylactic mastectomy. It is unknown if adding sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) to prophylactic mastectomy increases the risk of lymphedema. We sought to determine the risk of lymphedema after mastectomy with and without nodal evaluation. 117 patients who underwent bilateral mastectomy were prospectively screened for lymphedema. Perometer arm measurements were used to calculate weight-adjusted arm volume change at each follow-up. Of 234 mastectomies performed, 15.8 % (37/234) had no axillary surgery, 63.7 % (149/234) had SLNB, and 20.5 % (48/234) had axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). 88.0 % (103/117) of patients completed the LEFT-BC questionnaire evaluating symptoms associated with lymphedema. Multivariate analysis was used to assess clinical characteristics associated with increased weight-adjusted arm volume and patient-reported lymphedema symptoms. SLNB at the time of mastectomy did not result in an increased mean weight-adjusted arm volume compared to mastectomy without axillary surgery (p = 0.76). Mastectomy with ALND was associated with a significantly greater mean weight-adjusted arm volume change compared to mastectomy with SLNB (p < 0.0001) and without axillary surgery (p = 0.0028). Patients who underwent mastectomy with ALND more commonly reported symptoms associated with lymphedema compared to those with SLNB or no axillary surgery (p < 0.0001). Patients who underwent mastectomy with SLNB or no axillary surgery reported similar lymphedema symptoms. Addition of SLNB to mastectomy is not associated with a significant increase in measured or self-reported lymphedema rates. Therefore, SLNB may be performed at the time of prophylactic mastectomy without an increased risk of lymphedema.

Keywords: Prophylactic mastectomy, Breast cancer-related lymphedema, Sentinel lymph node biopsy, Bilateral mastectomy, Arm swelling

Introduction

Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is increasingly performed in patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Patients with a family history of breast cancer, a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation or simply a diagnosis of unilateral breast cancer may choose to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for risk reduction [1-5]. In fact, the number of women who opt for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy rose from 0.4 to 4.7 % from 1998 to 2007 [6].

Controversy exists regarding whether to routinely perform sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) at the time of prophylactic mastectomy. In the setting of a known invasive cancer, SLNB is routinely performed at the time of mastectomy to accurately stage the breast cancer [7]. Occult invasive cancers may be detected in approximately 1–3.5 % of prophylactic mastectomy specimens [8-11]. If no nodal evaluation is performed at the time of prophylactic mastectomy and an occult invasive cancer is found, patients must return to the operating room for an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND).

Staging the axilla with SLNB compared to ALND has been shown to decrease the risk of subsequent lymphedema and symptoms associated with lymphedema [12-21]. The reported incidence of measured lymphedema associated with SLNB ranges from 3.5 to 11 %, compared with up to 30 % in patients undergoing ALND [12, 21-23]. Similarly, patients who undergo ALND experience an increase in sensation changes associated with lymphedema such as tenderness, firmness/tightness, heaviness, and aching when compared with SLNB alone [15, 24-27]. Lymphedema remains one of the most-feared side effects of breast cancer treatment, and is known to cause significant physical and psychosocial detriments [28-31].

In this study, we sought to determine the risk of lymphedema in patients who underwent mastectomy with and without nodal evaluation. We analyzed changes in measured arm volumes and self-reported lymphedema symptoms to determine whether adding a SLNB to prophylactic mastectomy increases the risk of measured lymphedema or symptoms associated with lymphedema.

Methods and patients

Study design

Women undergoing treatment for breast cancer at our institution are prospectively screened for lymphedema using serial perometer arm volume measurements with the approval of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board [32]. Assessment for lymphedema in patients after bilateral breast surgery is particularly challenging, since lymphedema criteria are commonly based on comparison between the at-risk and contralateral arm. We therefore utilized a weight-adjusted arm volume change equation which calculates change in arm volume compared to a pre-operative measurement and accounts for temporal changes in patient weight. A similar BMI-adjusted arm volume change equation has previously been proposed [33]. For this study, weight-adjusted change was calculated for the left and right arm independently at each post-operative assessment according to the formula, weight-adjusted change = (A2*W1)/(W2*A1) – 1, where A1 is pre-operative arm volume, A2 is arm volume at a post-operative assessment, and W1 and W2 are the patient’s weights at these time points.

Patients

117 patients undergoing bilateral mastectomy from 2006 to 2011 were enrolled. Bilateral mastectomy was performed for bilateral breast cancer or for unilateral breast cancer with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Each patient had at least 3 months of post-surgical follow-up measurements, and 88.0 % (103/117) of patients completed a modified version of the Lymphedema Evaluation Following Treatment for Breast Cancer (LEFT-BC) Questionnaire at their most recent follow-up. We did not require that the bilateral mastectomy be performed as a single procedure. Each breast was considered individually, and mastectomies were divided into groups based on surgery type: mastectomy without axillary surgery, mastectomy with SLNB, and modified radical mastectomy (mastectomy with ALND). The decision to perform a SLNB at the time of prophylactic mastectomy was at the discretion of the patient and treating surgeon. In general, SLN biopsy was performed at the time of prophylactic mastectomy, unless the patient had a normal pre-operative breast MRI of the prophylactic breast. For the SLNB procedure, all patients received a subareolar injection of 0.52 mCi of filtered Tc-99m sulfur colloid. Some patients were also injected with methylene blue or lymphazurin at the discretion of the treating surgeon.

Of 234 individual mastectomies, 37/234 (15.8 %) were without axillary surgery, 149/234 (63.7 %) with SLNB, and 48/234 (20.5 %) with ALND. 45.3 % (106/234) of mastectomies were prophylactic, 34.0 % (36/106) without axillary surgery, and 66.0 % (70/106) with SLNB. Patient demographics, pathology, surgical, radiation, and medical oncology treatments were collected via medical record review.

Measured arm volume changes

Weight-adjusted arm volume change at each follow-up visit was used to indicate the presence of measured lymphedema. Measurements recorded within 3 months of surgery were not included for analysis, as patients may have experienced post-surgical arm volume increases unrelated to lymphedema during this time [34]. The median number of follow-up measurements after the 3 month post-op period was three per patient with a range of 1–9.

Lymphedema symptoms

Lymphedema symptom data was collected via patient self-report using the LEFT-BC Questionnaire which contained sections from multiple validated surveys utilized for lymphedema assessment [27, 35-37]. We administered a modified version of the LEFT-BC pertaining to symptoms experienced on each side at any time point greater than 3 months post-operative. Patients’ past history of lymphedema treatment was collected via patient self-report. Patients at our institution undergo routine perometer measurements, and if an arm volume increase is detected patients are encouraged to return for a follow-up measurement, at which time they are referred to physical therapy for stretching exercises and a compressive garment.

Questions pertaining to lymphedema symptoms from the LEFT-BC Questionnaire included:

Have you ever noticed that your arm, shoulder, neck, or hand felt larger?

Have you ever noticed that your sleeve, sleeve cuff, or ring felt tighter?

Have you ever noticed swelling or heaviness in your arm, hand, breast, or chest?

Statistical analysis

Multivariate mixed effects models were used to assess the association of clinical characteristics and lymphedema symptoms with mean weight-adjusted arm volume. These models account for the correlation between weight-adjusted arm volume measurements obtained from the same patient and on the same side of the body. Regional lymph node and chest wall radiation were not included as part of the multivariate analysis because both treatments are highly correlated with having undergone ALND and inclusion of these variables interferes with accurate estimation of the effect of surgery type. Generalized estimating equations models were used to assess the association of surgery type and lymphedema symptoms.

Results

Patient characteristics

91 % (106/117) of patients who underwent bilateral mastectomy had unilateral breast cancer but chose bilateral mastectomy, and 9 % (11/117) of patients underwent bilateral mastectomy for known bilateral breast cancer. The mean age at surgery was 47 years (range 23–69), and mean pre-operative BMI was 26 kg/m2 (range 17–51). Mean post-surgical follow-up was 29 months (range 3–64).

Of the 117 patients, 21 % (25/117) underwent unilateral SLNB with no contralateral axillary surgery, 40 % (47/117) underwent bilateral SLNB, 10 % (12/117) underwent ALND with no contralateral axillary surgery, 26 % (30/117) underwent ALND with contralateral SLNB, and 3 % (3/117) underwent bilateral ALND. Final pathology of mastectomy specimens revealed unilateral DCIS in 11 % (13/117), bilateral DCIS in 1 % (1/117), unilateral invasive cancer in 73 % (85/117), unilateral invasive cancer and contralateral DCIS in 6 % (7/117), and bilateral invasive cancer in 9 % (11/117). Median invasive tumor size was 1.8 cm (range 0.1–8.0). Median number of lymph nodes removed during SLNB was 1 (range 1–10) and during ALND was 15 (range 7–35). Occult cancers were identified in 7.5 % (8/106) of prophylactic mastectomies, 2.8 % (3/106) were invasive, and 4.7 % (5/106) non-invasive breast cancers. One of the three occult invasive cancers had a micrometastasis to the SLNB. The remaining two occult invasive cancers had a SLNB performed at the time of mastectomy that was negative for metastasis.

Patients who underwent mastectomy without axillary surgery and mastectomy with SLNB had similar mean age at surgery, mean pre-operative BMI, opted for similar types of reconstruction, received similar radiation and chemotherapy treatment, and had a similar mean follow-up. Patients who underwent ALND compared to those without axillary surgery or with SLNB were younger, more commonly received post-mastectomy radiation with or without nodal radiation and chemotherapy, and had longer mean follow-up (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics by surgery type

| Mastectomy without axillary surgery |

Mastectomy with SLNB |

P Value | Mastectomy with ALND |

P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 149 | No nodes versus SLNB |

n = 48 | ALND versus SLNB or No nodes |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Number | % or Range |

Number | % or Range |

Number | % or Range | |||

| Mean age at surgery (years) | 47 | 27–69 | 48 | 23–67 | 0.59 | 46 | 27–69 | 0.01 |

| Mean pre-surgical BMI (kg/m2) | 26 | 17–40 | 25 | 17–51 | 0.70 | 27 | 19–41 | 0.11 |

| Mean post-surgical follow-up (months) | 29 | 3–57 | 28 | 3–64 | 0.76 | 29 | 3–64 | 0.01 |

| Median # of LN removed | 0 | 0–0 | 1 | 1–10 | – | 15 | 7–35 | <0.0001 |

| Median # positive LNs | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | 0–3 | – | 2 | 0–16 | <0.0001 |

| Reconstruction | 0.46 | 0.07 | ||||||

| None | 4 | 11 % | 10 | 7 % | 10 | 21 % | ||

| Expanders | 22 | 59 % | 75 | 50 % | 22 | 46 % | ||

| Immediate implant | 8 | 22 % | 49 | 33 % | 11 | 23 % | ||

| Autologous | 3 | 8 % | 15 | 10 % | 5 | 10 % | ||

| Radiation therapy | ||||||||

| Chest wall | 0 | 0 % | 6 | 4 % | – | 40 | 83 % | <0.0001 |

| Chest wall + nodal | 0 | 0 % | 3 | 2 % | – | 31a | 71 % | <0.0001 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.31 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 25 | 68 % | 87 | 58 % | 48 | 100 % | ||

| No | 12 | 32 % | 62 | 42 % | 0 | 0 % | ||

4 unknown for nodal radiation fields

BMI body mass index, LN lymph node

Measured arm volume changes

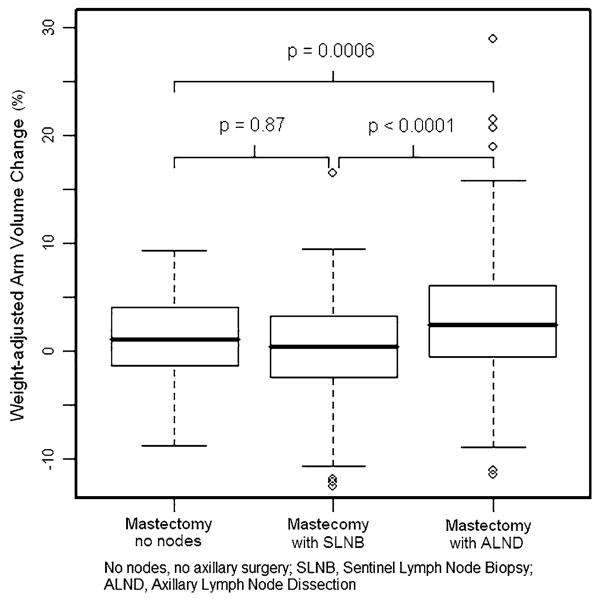

By univariate analysis, there was no significant difference in mean weight-adjusted arm volume change between mastectomy with SLNB and mastectomy without axillary surgery (p = 0.87). For the 106 prophylactic mastectomy cases (excluding those performed for known carcinoma), there was also no significant increase in mean weight-adjusted arm volume change for mastectomy with SLNB compared to no axillary surgery (p = 0.22). Mastectomy with ALND had a significantly higher mean weight-adjusted arm volume compared to mastectomy without axillary surgery (p = 0.0006) or with SLNB (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). Univariate analysis demonstrated no increase in mean weight-adjusted arm volume change of the ipsilateral arm for patients who underwent mastectomy with SLNB on the opposite side (p = 0.098). Mastectomy with ALND on the opposite side resulted in a significantly decreased mean weight-adjusted arm volume change in the ipsilateral arm (p = 0.0041).

Fig. 1.

Mean weight-adjusted arm volume change by surgery type

By multivariate analysis, mastectomy with SLNB did not result in greater mean weight-adjusted arm volume change compared to mastectomy without axillary surgery, with means of 0.29 and 0.39 %, respectively (p = 0.76). Mastectomy with ALND was associated with a significantly higher mean weight-adjusted arm volume change of 2.89 % compared to mastectomy with SLNB (p < 0.0001) or no axillary surgery (p = 0.0028). Increased mean weight-adjusted arm volume change was associated with ALND and not with BMI or type of reconstruction by multivariate analysis. Type of surgery on the contralateral side did not contribute significantly to the multivariate model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of clinical characteristics associated with mean weight-adjusted arm volume change

| Mean WAC (%) |

Lower CI (%) |

Upper CI (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference groupa | 1.72 | −0.30 | 3.73 | – |

| Clinical characteristic | ||||

| BMIb | 2.18 | 0.16 | 4.21 | 0.17 |

| Surgery type | ||||

| SLNB | 1.52 | −0.28 | 3.32 | 0.76 |

| ALND | 3.93 | 2.08 | 5.78 | 0.0028 (vs. no nodes) <0.0001 (vs. SLNB) |

| Reconstruction | ||||

| Tissue expander | 0.10 | −1.25 | 1.46 | 0.10 |

| Single-stage implant | −0.30 | −1.96 | 1.35 | 0.06 |

| Autologous | 2.01 | −0.11 | 4.12 | 0.80 |

Reference group includes patients with BMI = 24 (median), non-nodal surgery, and no reconstruction

Mean WAC for BMI = 30

WAC weight-adjusted arm volume change, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, No nodes no axillary surgery, SLNB sentinel lymph node biopsy, ALND axillary lymph node dissection

Lymphedema symptoms

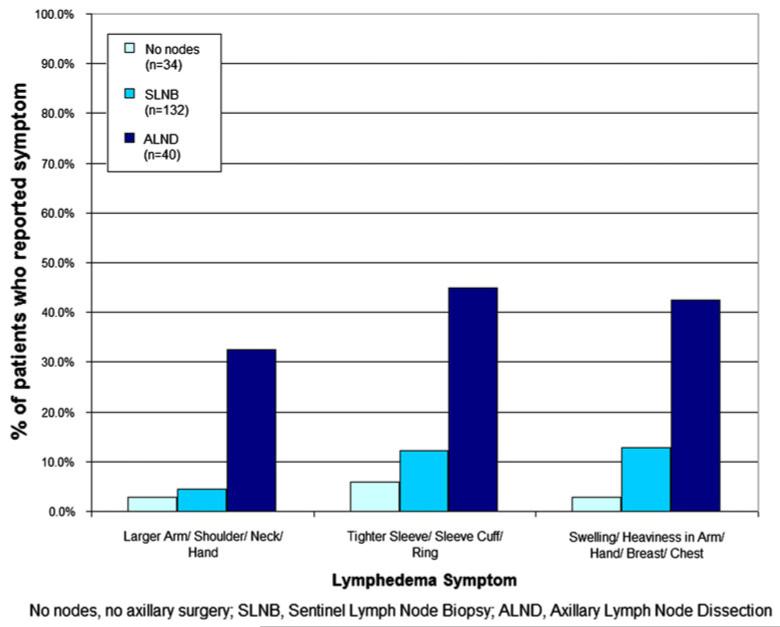

Patients who underwent mastectomy with SLNB reported a similar incidence of lymphedema symptoms compared with patients who underwent mastectomy without axillary surgery. There was no significant difference in reported rates of larger arm, shoulder, neck, or hand (p = 0.92); tighter sleeve, sleeve cuff or ring (p = 0.98); or swelling or heaviness in the arm, hand, breast, or chest (p = 0.12). Patients who underwent mastectomy with ALND more commonly reported symptoms of: larger arm, shoulder, neck, or hand (p < 0.0001); tighter sleeve, sleeve cuff, or ring (p < 0.0001); and swelling or heaviness in the arm, hand, breast, or chest (p < 0.0001) compared to patients who underwent mastectomy with SLNB or without axillary surgery (Fig. 2). Patients who reported lymphedema symptoms of larger arm, shoulder, neck, or hand (p = 0.0014) had a statistically significant increased mean weight-adjusted arm volume change by multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Patient-reported lymphedema symptoms by surgery type

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of patient-reported lymphedema symptoms associated with mean weight-adjusted volume change

| Mean WAC (%) |

Lower CI (%) |

Upper CI |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference groupa | 0.11 | −0.65 | 0.87 | – |

| Larger arm/shoulder/neck/ hand |

3.35 | 1.30 | 5.39 | 0.0014 |

| Tighter sleeve/sleeve cuff/ ring |

0.77 | −0.94 | 2.48 | 0.4131 |

| Swelling or heaviness in arm/hand/breast/chest |

1.78 | 0.01 | 3.54 | 0.0562 |

Reference group includes patients who did not report any lymphedema symptoms

WAC weight-adjusted arm volume change, CI confidence interval

Lymphedema treatment

Of 117 patients, only those who underwent mastectomy with ALND reported having received treatment for lymphedema. Of the 48 mastectomies performed with ALND, 22.9 % (11/48) underwent consultation with a lymphedema physical therapist and upper extremity exercises, and 8 of the 11 underwent treatment with compression sleeve. By univariate analysis, lymphedema treatment was associated with a significantly increased mean weight-adjusted arm volume change for the ipsilateral arm, with a mean of 6.50 % (p < 0.0001). Lymphedema treatment on the opposite side was significantly associated with a decreased mean weight-adjusted arm volume change in the ipsilateral arm (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to evaluate the risk of lymphedema after mastectomy with or without nodal evaluation. In our cohort with a mean follow-up of 29 months, the addition of a SLNB to mastectomy did not result in a significantly higher risk of measured lymphedema, nor did patients who underwent mastectomy with SLNB report a significantly higher incidence of symptoms associated with lymphedema.

Prophylactic mastectomy is increasingly performed for patients at high risk for or with diagnosis of breast cancer. However, the routine use of SLNB at the time of prophylactic mastectomy remains controversial. Proponents of routine SLNB note that occult invasive cancers are detected in 1–3.5 % of prophylactic mastectomy specimens [8-11]. 2.8 % of women in our cohort were found to have invasive cancers in their prophylactic mastectomy specimens, which may be in part due to non-routine use of pre-operative breast MRI. However, all three patients had pre-operative evaluation with a breast MRI, one of the MRIs demonstrated a suspicious lesion on the prophylactic side, and the decision was made not to biopsy because bilateral mastectomy was planned, one MRI demonstrated a probably benign lesion on the prophylactic side for which 6-month follow-up was recommended, and the final breast MRI was normal, however, limited due to motion artifact and marked background enhancement.

Patients found to have occult invasive cancers after prophylactic mastectomy without SLNB are committed to ALND, which increases the risk of lymphedema, pain, sensory disturbances, and shoulder dysfunction [19, 22, 38,39]. In our cohort, two of 106 patients who underwent contralateral prophylactic mastectomy were spared subsequent axillary lymph node dissection because a SLNB was performed at the time of their prophylactic mastectomy. Furthermore, the addition of SLNB to prophylactic mastectomy does not have to compromise cosmesis. Kiluk et al. [40] demonstrated the feasibility of performing SLNB through an inframammary incision for nipple sparing mastectomy without a second axillary incision.

Opponents of SLNB note that although SLNB results in lower morbidity than ALND, the procedure may be associated with post-operative complications including lymphedema, seroma formation, limited arm mobility, and sensory morbidity [12, 15, 17, 19, 24, 25, 41–45]. In fact, studies have reported an incidence of lymphedema following SLNB in the range of 3.5–11 % [12, 21–23]. However, the majority of these studies evaluated the morbidity of SLNB at the time of lumpectomy and not mastectomy and therefore may not accurately assess the risks of SLNB in the setting of prophylactic mastectomy. Although it was not found to be of statistical significance in this analysis, our data suggests a trend toward increased lymphedema symptoms reported by patients with SLNB compared to those without axillary surgery. This should be further explored in a larger sample of patients with greater follow-up. Opponents of prophylactic SLNB also note that the incidence of an occult invasive cancer detected at the time of prophylactic mastectomy is rare. In a recent metaanalysis of 1,343 prophylactic mastectomy specimens, Zhou et al. [46] reported a 1.7 % incidence of occult invasive cancers. In this analysis, only 1.2 % of patients were spared an axillary lymph node dissection because a SLNB was performed at the time of prophylactic mastectomy and an invasive occult cancer was discovered.

Others promote selective use of SLNB at the time of prophylactic mastectomy [47]. In patients who have undergone a breast MRI pre-operatively either due to a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation or for further evaluation of the primary tumor, the incidence of occult contralateral invasive cancer is low [10]. Therefore, SLNB is omitted at the time of mastectomy with a normal pre-operative breast MRI. However, pre-operative breast MRI simply for nodal evaluation is not recommended due to the increased costs associated with performing a breast MRI to rule out a contralateral occult invasive cancer compared with the costs of performing a SLNB at the time of mastectomy [48]. Based on the results of our study, SLNB may safely be performed at the time of prophylactic mastectomy for axillary staging without an increased risk of lymphedema.

SLNB is also selectively performed at the time of contralateral mastectomy in patients with inflammatory or locally advanced breast cancer to identify contralateral metastases from the primary tumor which would reclassify the patient as Stage IV. In our series, for patients who underwent mastectomy with ALND, we did not see an increased risk of lymphedema in the arm on the opposite side, which could occur due to lymphatic damage caused by ALND and subsequent lymph flow to the contralateral side [49]. In fact, patients had a significant reduction in mean weight-adjusted volume change in the arm on the side opposite to mastectomy with ALND. In addition, patients who were treated for lymphedema experienced a reduced mean volume change in the arm on the opposite side, which may be due to adherence to upper extremity exercises bilaterally.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature, the non-randomized selection of patients for SLNB versus no nodal analysis at the time of mastectomy, and the relatively small sample size. Of note, the mean length of follow-up for the cohort who underwent modified radical mastectomy was 1 month greater than follow-up for patients who underwent mastectomy with or without SLNB. This should not result in a bias as most patients returned to follow-up at 3 month intervals. Symptoms associated with lymphedema may be under-reported since this information was captured at the most recent follow-up, at which time patients may not have been able to recall symptoms that occurred at an earlier time. Finally, our analysis included mastectomies performed for both treatment and prophylactic purposes. Therefore, applicability to the strictly prophylactic setting may be limited. Owing to these limitations, further research is warranted using a larger cohort of patients with increased follow-up to confirm our findings regarding lymphedema risk after mastectomy with and without SLNB.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the addition of SLNB to mastectomy does not significantly increase the risk of lymphedema. Patients for whom an occult invasive cancer may be suspected, such as those without pre-operative breast MRI or those with a BIRADS three pre-operative imaging, would benefit from SLNB to reduce the risk of subsequent axillary lymph node dissection. In addition, patients with a locally advanced or inflammatory breast cancer who opt for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy may undergo SLNB on the prophylactic side to rule out contralateral axillary metastasis without an increased risk of lymphedema.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01CA139118 (AGT), Award Number P50CA089393 (AGT) from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CL Miller, MN Skolny, LS Jammallo, N Horick, J O’Toole, K Hughes, M Gadd, BL Smith, AG Taghian, Michelle C. Specht. Risk of Lymphedema after Prophylactic Mastectomy. 13th Annual American Society of Breast Surgeons Conference. Phoenix, Arizona. May 2–6, 2012, poster presentation.

Cynthia L Miller and Michelle C Specht —Co-first authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Cynthia L. Miller, Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Michelle C. Specht, Division of Surgical Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Melissa N. Skolny, Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Lauren S. Jammallo, Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Nora Horick, Department of Biostatistics, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Jean O’Toole, Department of Physical and Occupational Therapy, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Suzanne B. Coopey, Division of Surgical Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Kevin Hughes, Division of Surgical Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Barbara L. Smith, Division of Surgical Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Alphonse G. Taghian, Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

References

- 1.Schrag D, Kuntz KM, Garber JE, Weeks JC. Life expectancy gains from cancer prevention strategies for women with breast cancer and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. JAMA. 2000;283(5):617–624. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.5.617. doi:10.1001%2Fjama.283.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuttle TM, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, Arrington A, Abraham A, Morris TJ, Virnig BA. Increasing rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1362–1367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1681. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, Morris TJ, Virnig BA. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5203–5209. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3141. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonnell SK, Schaid DJ, Myers JL, Grant CS, Donohue JH, Woods JE, Frost MH, Johnson JL, Sitta DL, Slezak JM, Crotty TB, Jenkins RB, Sellers TA, Hartmann LC. Efficacy of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a personal and family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(19):3938–3943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.19.3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrinton LJ, Barlow WE, Yu O, Geiger AM, Elmore JG, Barton MB, Harris EL, Rolnick S, Pardee R, Husson G, Macedo A, Fletcher SW. Efficacy of prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer: a cancer research network project. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(19):4275–4286. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.080. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao K, Stewart AK, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral cancer: a report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2007. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(10):2554–2562. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1091-3. doi:10.1245/s10434-010-1091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim T, Giuliano AE, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast carcinoma: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;106(1):4–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21568. doi:10.1002/cncr.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boughey JC, Khakpour N, Meric-Bernstam F, Ross MI, Kuerer HM, Singletary SE, Babiera GV, Arun B, Hunt KK, Bedrosian I. Selective use of sentinel lymph node surgery during prophylactic mastectomy. Cancer. 2006;107(7):1440–1447. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22176. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont EL, Kuhn MA, McCann C, Salud C, Spanton JL, Cox CE. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in women undergoing prophylactic mastectomy. Am J Surg. 2000;180(4):274–277. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin SA, Stempel M, Morris EA, Liberman L, King TA. Can magnetic resonance imaging be used to select patients for sentinel lymph node biopsy in prophylactic mastectomy? Cancer. 2008;112(6):1214–1221. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23298. doi:10.1002/cncr.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laronga C, Lee MC, McGuire KP, Meade T, Carter WB, Hoover S, Cox CE. Indications for sentinel lymph node biopsy in the setting of prophylactic mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(6):746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.010. quiz 800-741. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilke LG, McCall LM, Posther KE, Whitworth PW, Reintgen DS, Leitch AM, Gabram SG, Lucci A, Cox CE, Hunt KK, Herndon JE, II, Giuliano AE. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node biopsy: results from a prospective international cooperative group trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(4):491–500. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.013. doi:10.1245/ASO.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Reintgen DS, Blumencranz PW, Leitch AM, Saha S, Hunt KK, Giuliano AE. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3657–3663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin SA, Wright MJ, Morris KT, Sampson MR, Brockway JP, Hurley KE, Riedel ER, Van Zee KJ. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: patient perceptions and precautionary behaviors. J Clin Oncol. 2008 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3766. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008. 16.3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron RH, Fey JV, Borgen PI, et al. Eighteen sensations after breast cancer surgery: a 5-year comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary lymph node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(5):1653–1661. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haid A, Kuehn T, Konstantiniuk P, Koberle-Wuhrer R, Knauer M, Kreienberg R, Zimmermann G. Shoulder-arm morbidity following axillary dissection and sentinel node only biopsy for breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28(7):705–710. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1327. doi:10.1053/ejso.2002.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golshan M, Martin WJ, Dowlatshahi K. Sentinel lymph node biopsy lowers the rate of lymphedema when compared with standard axillary lymph node dissection. Am Surg. 2003;69(3):209–211. discussion 212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleissig A, Fallowfield LJ, Langridge CI, Johnson L, Newcombe RG, Dixon JM, Kissin M, Mansel RE. Post-operative arm morbidity and quality of life. Results of the ALMANAC randomised trial comparing sentinel node biopsy with standard axillary treatment in the management of patients with early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95(3):279–293. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9025-7. doi:10.1007/s10549-005-9025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Temple LK, Baron R, Cody HS, III, Fey JV, Thaler HT, Borgen PI, Heerdt AS, Montgomery LL, Petrek JA, Van Zee KJ. Sensory morbidity after sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection: a prospective study of 233 women. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(7):654–662. doi: 10.1007/BF02574481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronka R, von Smitten K, Tasmuth T, Leidenius M. One-year morbidity after sentinel node biopsy and breast surgery. Breast. 2005;14(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.09.010. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, Goyal A, Newcombe RG, Dixon JM, Yiangou C, Horgan K, Bundred N, Monypenny I, England D, Sibbering M, Abdullah TI, Barr L, Chetty U, Sinnett DH, Fleissig A, Clarke D, Ell PJ. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(9):599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer I, Guller U, Berclaz G, Koechli OR, Schaer G, Fehr MK, Hess T, Oertli D, Bronz L, Schnarwyler B, Wight E, Uehlinger U, Infanger E, Burger D, Zuber M. Morbidity of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLN) alone versus SLN and completion axillary lymph node dissection after breast cancer surgery: a prospective Swiss multicenter study on 659 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245(3):452–461. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245472.47748.ec. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000245472.47748.ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin SA, Wright MJ, Morris KT, Giron GL, Sampson MR, Brockway JP, Hurley KE, Riedel ER, Van Zee KJ. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: objective measurements. J Clin Oncol. 2008 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3725. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rietman JS, Geertzen JH, Hoekstra HJ, Baas P, Dolsma WV, de Vries J, Groothoff JW, Eisma WH, Dijkstra PU. Long term treatment related upper limb morbidity and quality of life after sentinel lymph node biopsy for stage I or II breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32(2):148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.11.008. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulze T, Mucke J, Markwardt J, Schlag PM, Bembenek A. Long-term morbidity of patients with early breast cancer after sentinel lymph node biopsy compared to axillary lymph node dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(2):109–119. doi: 10.1002/jso.20406. doi:10.1002/jso.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cormier JN, Xing Y, Zaniletti I, Askew RL, Stewart BR, Armer JM. Minimal limb volume change has a significant impact on breast cancer survivors. Lymphology. 2009;42(4):161–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armer JM, Radina ME, Porock D, Culbertson SD. Predicting breast cancer-related lymphedema using self-reported symptoms. Nurs Res. 2003;52(6):370–379. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes SC, Janda M, Cornish B, Battistutta D, Newman B. Lymphedema after breast cancer: incidence, risk factors, and effect on upper body function. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3536–3542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4899. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed RL, Prizment A, Lazovich D, Schmitz KH, Folsom AR. Lymphedema and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4731. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakorafas GH, Peros G, Cataliotti L, Vlastos G. Lymphedema following axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(3):153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2006.11.003. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jager G, Doller W, Roth R. Quality-of-life and body image impairments in patients with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2006;39(4):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ancukiewicz M, Russell TA, Otoole J, Specht M, Singer M, Kelada A, Murphy CD, Pogachar J, Gioioso V, Patel M, Skolny M, Smith BL, Taghian AG. Standardized method for quantification of developing lymphedema in patients treated for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(5):1436–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahamaneerat WK, Shyu CR, Stewart BR, Armer JM. Breast cancer treatment, BMI, post-op swelling/lymphoedema. J Lymphoedema. 2008;3(2):38–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armer JM, Stewart BR, Shook RP. 30-month post-breast cancer treatment lymphoedema. J Lymphoedema. 2009;4(1):14–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solway S, Beaton DE, McConnell S, Bombardier C. The DASH outcome measure user’s manual. 2nd edn Institute for Work and Health; Toronto: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee TS, Kilbreath SL, Sullivan G, Refshauge KM, Beith JM. The development of an arm activity survey for breast cancer survivors using the Protection Motivation Theory. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-75. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, Deasy S, Cobleigh M, Shiomoto G. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warmuth MA, Bowen G, Prosnitz LR, Chu L, Broadwater G, Peterson B, Leight G, Winer EP. Complications of axillary lymph node dissection for carcinoma of the breast: a report based on a patient survey. Cancer. 1998;83(7):1362–1368. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981001)83:7<1362::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-2. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981001)83:7<1362:AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hack TF, Cohen L, Katz J, Robson LS, Goss P. Physical and psychological morbidity after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):143–149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiluk JV, Santillan AA, Kaur P, Laronga C, Meade T, Ramos D, Cox CE. Feasibility of sentinel lymph node biopsy through an inframammary incision for a nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(12):3402–3406. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0156-z. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-0156-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baron RH, Fey JV, Raboy S, Thaler HT, Borgen PI, Temple LK, Van Zee KJ. Eighteen sensations after breast cancer surgery: a comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary lymph node dissection. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(4):651–659. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.651-659. doi:10.1188/02.ONF.651-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Land SR, Kopec JA, Julian TB, Brown AM, Anderson SJ, Krag DN, Christian NJ, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, Ganz PA. Patient-reported outcomes in sentinel node-negative adjuvant breast cancer patients receiving sentinel-node biopsy or axillary dissection: national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project phase III protocol B-32. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):3929–3936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.2491. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.28.2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leidenius M, Leivonen M, Vironen J, von Smitten K. The consequences of long-time arm morbidity in node-negative breast cancer patients with sentinel node biopsy or axillary clearance. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92(1):23–31. doi: 10.1002/jso.20373. doi:10.1002/jso.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soran A, Falk J, Bonaventura M, Keenan D, Ahrendt G, Johnson R. Is routine sentinel lymph node biopsy indicated in women undergoing contralateral prophylactic mastectomy? Magee-Womens Hospital experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(2):646–651. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9264-9. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boughey JC, Cormier JN, Xing Y, Hunt KK, Meric-Bernstam F, Babiera GV, Ross MI, Kuerer HM, Singletary SE, Bedrosian I. Decision analysis to assess the efficacy of routine sentinel lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing prophylactic mastectomy. Cancer. 2007;110(11):2542–2550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23067. doi:10.1002/cncr.23067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou WB, Liu XA, Dai JC, Wang S. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy at the time of prophylactic mastectomy of the breast. Can J Surg. 2011;54(5):300–306. doi: 10.1503/cjs.006010. doi:10.1503/cjs.006010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasser SM, Smith SG, Chagpar AB. The role of sentinel node biopsy in women undergoing prophylactic mastectomy. J Surg Res. 2010;164(2):188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.020. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Black D, Specht M, Lee JM, Dominguez F, Gadd M, Hughes K, Rafferty E, Smith B. Detecting occult malignancy in prophylactic mastectomy: preoperative MRI versus sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(9):2477–2484. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9356-1. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perre CI, Hoefnagel CA, Kroon BB, Zoetmulder FA, Rutgers EJ. Altered lymphatic drainage after lymphadenectomy or radiotherapy of the axilla in patients with breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83(9):1258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1996.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]