ABSTRACT

Purpose: To investigate the concurrent validity of the Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium's Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm (FSRA). Method: A total of 29 older adults (mean age 77.7 [SD 4.0] y) residing in an independent-living senior's complex who met inclusion criteria completed a demographic questionnaire and the components of the FSRA and Berg Balance Scale (BBS). The FSRA consists of the Elderly Fall Screening Test (EFST) and the Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire (MFQ); it is designed to categorize individuals into low, moderate, or high fall-risk categories to determine appropriate management pathways. A predictive model for probability of fall risk, based on previous research, was used to determine concurrent validity of the FSRI. Results: The FSRA placed 79% of participants into the low-risk category, whereas the predictive model found the probability of fall risk to range from 0.04 to 0.74, with a mean of 0.35 (SD 0.25). No statistically significant correlation was found between the FSRA and the predictive model for probability of fall risk (Spearman's ρ=0.35, p=0.06). Conclusion: The FSRA lacks concurrent validity relative to to a previously established model of fall risk and appears to over-categorize individuals into the low-risk group. Further research on the FSRA as an adequate tool to screen community-dwelling older adults for fall risk is recommended.

Key Words: algorithms; aged; falls, accidental; reproducibility of results; risk assessment

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Étudier la validité concurrente de l'algorithme de dépistage des risques de chute et de renvoi en consultation (Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm, FSRA) du Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium. Méthode : Vingt-neuf personnes âgées (moyenne d'âge [ET] de 77,7 ans [4,0]) vivant dans une résidence pour personnes âgées autonomes satisfaisaient les critères d'inclusion; elles ont rempli un questionnaire démographique et ont été soumises à certaines composantes du FSRA et du test d'équilibre de l'échelle de Berg (EEB). Le FSRA comprend un test de dépistage des risques de chute (Elderly Fall Screening Test, EFST) et le questionnaire multifactoriel en matière de chutes (Multi-Factor Falls Questionnaire, MFQ). Il est conçu pour classer les individus dans trois catégories – risque de chute élevé, modéré ou faible – afin d'établir les approches de gestion appropriées. Un modèle prédictif de probabilité des risques de chute basé sur une étude antérieure a été utilisé pour établir la validité concurrente du FRSA. Résultats : Au total, 79 % des participants ont été classés dans la catégorie à faible risque du FSRA, puisque le modèle prédictif a permis d'établir la probabilité des risques de chute dans leur cas entre 0,04 et 0,74, avec une moyenne de 0,35 (ET=0,25). On n'a pu établir aucune corrélation significative sur le plan statistique entre le FSRA et le modèle prédictif de la probabilité des risques de chute (ρ de Spearman=0,35, p=0,06). Conclusion : Le FSRA manque de validité concurrente si on le compare à un modèle de risques de chute préalablement établi et semble « surclasser » les individus dans le segment à faible risque. D'autres études sur le FSRA en tant qu'outil approprié de dépistage chez les aînés résidant dans la communauté sont recommandées.

Mots clés : chutes accidentelles, aînés, algorithmes, évaluation des risques, validité

Falling is a major health concern within the older adult population.1,2 In Canada, it is estimated that one in every three older adults will experience a fall in any given year3 and that up to 50% will experience repeated falls.4–9 Adults over age 65 are 9 times as likely to fall as the remainder of the population, and fall risk increases with increasing age.10 Falls have serious personal sequelae, including loss of confidence and increased fear of falling;2 increased disability, frailty, and mortality;2 and decreased activity levels, quality of life, and overall health status.11 Falls are also responsible for 90% of all hip fractures in the older adult population; the mortality rate after hip fracture is 20% within 1 year after injury.10

Falls and fall-related injuries impose a significant financial burden on the healthcare system.2 In Canada, falls in people over age 65 account for 84% of injury-related hospital admissions10,12 and 40% of nursing-home admissions.10 Canada's direct health care cost related to falls in the older adult population is an estimated $1 billion per year.12 In Saskatchewan, more than $56 million was spent in 1998 to treat people aged ≥65 following a fall.3,13 These costs are expected to increase with the growth of Canada's older adult population, predicted to more than double (to approximately 9.8 million) by 2036.12 A 20% reduction in falls would translate to an estimated 7,500 fewer hospitalizations and 1,800 fewer permanently disabled older adults, and would thus save $138 million per year across Canada.3 Clearly, it is of paramount importance to identify older adults who are at greatest risk of falling, and determine any modifiable risk factors for these individuals, to alleviate both the personal costs to individuals (i.e., injury, disability, mortality) and the financial costs to the health system.

A fall has been defined as an event in which a sudden unintentional change in position results in landing at a lower level (on an object, the floor, or the ground), with or without injury.1,11,14 Falls in the older adult population do not have a single well-defined aetiology. Fall risk is multi-factorial, with physiologic and environmental contributors interacting with behaviour and chronic predisposing diseases, and multiple risk factors increase the risk of falling.1,14 Risk factors for falling include a history of a previous fall, muscle weakness, balance problems, decreased physical activity levels, comorbidities such as arthritis, psychosocial factors, gait impairments, cognitive impairments, sensory impairments, multiple drug therapy, postural hypotension, and cardiac disorders.1,14–18 Appropriate identification of fall risk factors is a necessary component of fall screening and prevention programmes for older adults.14

Regardless of the setting, determining appropriate interventions for fall prevention begins with assessing fall risk. By identifying those at risk of falling, especially in community settings, health professionals can target fall-prevention programmes to those most likely to benefit from them. A comprehensive assessment evaluating the various age-related, biological, behavioural, cognitive, lifestyle, and environmental factors related to falls, although ideal, can be time consuming.19 In addition, a comprehensive assessment does not necessarily provide a fall risk “score” or categorization that can be interpreted easily and consistently.20 Several screening tools for identifying older adults at risk of falling have been developed21 for long-term care, acute-care, and community settings; these tools vary in administration time and complexity.21 A brief assessment tool with high specificity that could be used by front-line health care workers without specialized equipment is considered ideal for fall-risk screening in the community setting, to ensure that (1) those individuals with the lowest risk are screened out and (2) those with higher risk are referred for a more detailed fall-risk assessment and intervention plan carried out by highly trained professionals.20

It is important to note that there is no consensus on what the terms low, moderate, and high fall risk mean with respect to the probability of future fall risk, which leaves the magnitude of fall risk open to interpretation. Furthermore, the term low risk does not mean no risk, nor does it necessarily indicate negligible risk or decreased risk. For example, studies evaluating the predictive validity of the American Geriatric Society / British Geriatrics Society fall-screening algorithm have demonstrated that people assigned to the algorithm's low-risk group have a future fall risk roughly equal to 30%, the overall annual population fall risk for community-dwelling older adults.22,23

A recent systematic review found 23 risk-assessment tools that can be used with community-dwelling older adults, defined as people living independently in their own home or in a retirement community.21 Scott and colleagues21 reported that of these 23 tools, the majority are functional mobility assessments that focus on the physiologic and functional domains of postural stability (i.e., strength, balance, gait, and reaction times).21 Only two were described as multi-factorial assessment tools consisting of questions used to screen the level and nature of risk based on a combined score of multiple factors known to be associated with fall-related risk.21

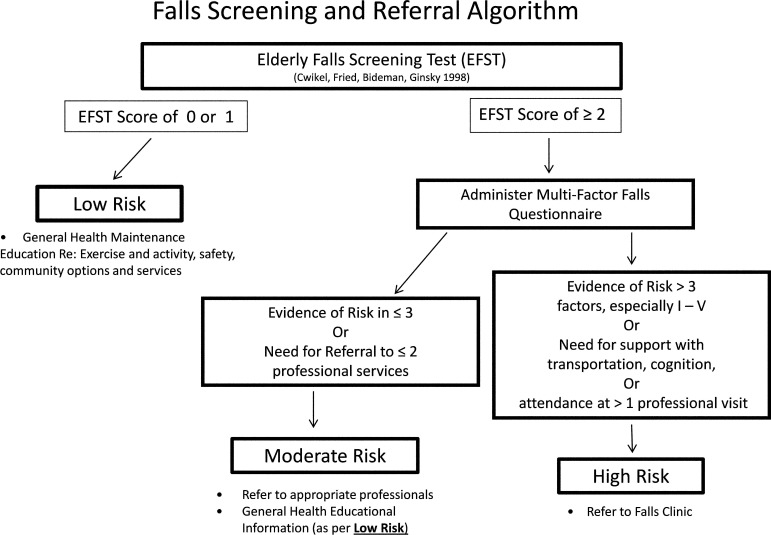

The Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium (SFPC) is a partnership of public and private health organizations, health care professionals, and members of the community who work collaboratively to plan, implement, and evaluate coordinated and comprehensive strategies to reduce falls and fall-related injuries in the older adult population in Saskatoon and across Saskatchewan.24 The SFPC developed the Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm (FSRA) in an effort to meet the need for a multi-factorial assessment tool that could be easily administered in the community setting, without special equipment, by a variety of health care providers. The FSRA (see Appendix 1 online) is made up of the Elderly Fall Screening Test25 (EFST) and the Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire24 (MFQ; see Appendix 2 online). The FSRA is intended to stratify older adults into a low-, moderate-, or high-fall-risk category to determine the appropriate management pathway. Once the fall-risk category has been determined, management pathways provide recommended options for fall prevention and intervention, including more detailed assessments, investigations, and individually tailored interventions for those in moderate- and high-risk categories (see Appendix 1).

Any screening tool used in clinical practice needs to provide reliable estimates of performance and evidence for use.20 The purpose of our study, therefore, was to examine the concurrent validity of the FSRA as a fall-risk screening tool for community-dwelling older adults. Concurrent validity is the degree to which a measure is comparable to a standardized measurement, or “gold standard.”26 Currently, however, no gold standard tool exists to screen for fall risk. We therefore chose Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model of fall risk1 as the comparator for our study (see description below). We hypothesized that the FSRA would be a valid tool for stratifying community-dwelling individuals aged 65–85 years into low-, moderate-, and high-fall-risk categories when compared to Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model.1

METHODS

The study protocol was approved by the University of Saskatchewan's Biomedical Research Ethics Board, and informed consent was obtained from all participants before any data collection took place.

Participants

Participants were recruited from a local independent-living seniors' housing complex using advertisements placed throughout the facility and were included in the study if they were aged 65–85 and able to walk 5 m without assistance from another person. Exclusion criteria were (1) any medical condition that significantly predisposes a person to falling (e.g., Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, previous stroke, Ménière's disease); (2) an acute injury; and/or (3) surgery within 6 months before the testing date. Because participants would be completing several self-report function measures, we also did not include people with a diagnosis of dementia or significant cognitive impairments. The Mini-Mental State Exam,27 a common screening tool for cognitive impairment, was used to evaluate cognitive status; people who scored <24, a score indicative of cognitive impairment, were excluded. A sample of 29 older adults met inclusion criteria and participated in the study.

Procedures

Prior to data collection, we pilot-tested the study procedures to ensure consistency in instructions to participants, administration of measures, and scoring of the FSRA components and the BBS (a component of Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model1). All participants completed a health status and demographic questionnaire (date of birth; weight; height; primary language; past medical history; medication use; and use of visual, hearing, and assistive devices).

Measures

All participants completed the EFST,25 the MFQ,24 and the BBS.28 These measures are described in detail below.

Elderly Fall Screening Test

The EFST, a brief screening tool, was developed by Cwikel and colleagues as part of a study investigating the feasibility of preventive interventions among community-dwelling older adults.25 Cwikel and colleagues25 reported the sensitivity and specificity of the EFST for identifying those at risk of falling as 83% and 69%, respectively. The EFST consists of five items: three questions about previous falls and balance problems; observation of gait cadence; and observation of gait pattern while walking at a normal pace over a 5 m distance.25 Each question is assigned a value of either 0 (no concern or abnormalities) or 1 (a positive score); values are then summed for a total score.25 According to the FSRA, a person scoring 0 or 1 on the EFST is identified as having a low risk of falling, and no further measures are administered. Individuals who score ≥2 on the EFST are stratified into either a moderate- or high-fall-risk category (see Appendix 1).

Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire

The next step of the FSRA is to administer the MFQ (see Appendix 2) for those with an EFST score ≥2. The MFQ consists of a checklist of known fall risk factors, divided into a General category and 10 specific Factor categories. A person is categorized as having a moderate risk of falling if the evaluator identifies ≤3 MFQ risk factors and as having a high risk of falling if there is evidence of >3 MFQ risk factors, especially in Factor I (Syncope / Drop Attack / Sudden Unexplained Falls), II (Sensory Problems), III (Medication Risk), IV (Acute or Significant Medical Problems), or V (Indication of Cognitive Problems) categories (see Appendix 2). Total MFQ scores were calculated as the sum of scores obtained for all 10 factors, excluding the “General” factor/category. A score of 1 was assigned to a factor if any of its items were endorsed, except for the Factor VI sub-question “Where have you fallen?” Using this scoring procedure, possible scores for the MFSQ ranged from 0 to 10.

Berg Balance Scale

The BBS, a 14-item battery that assesses a person's ability to safely perform several common daily living tasks, is widely used by health professionals to assess balance and fall risk.28–31 Performance on each item is rated on a scale from 0 (cannot perform the task) to 4 (normal performance of the task); the maximum score is 56. The BBS has been reported to have excellent interrater and intrarater reliability and concurrent validity and to be capable of discriminating older adults at risk for falls.1,28–31 Scores obtained from the BBS were used in Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model,1 as described below.

Probability of falling

Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model1 was chosen as the comparator for this study because an equivalent “gold standard” measure that categorizes fall risk in terms of low, medium, and high risk was not found in the literature. The logistic predictive model developed by Shumway-Cook and colleagues, which consists of history of imbalance and BBS scores, has been found to have high levels of sensitivity (91%) and specificity (82%) in identifying fallers and non-fallers.1 The following equation was used to calculate probability of falling:

Data analysis

Our data analysis used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). We calculated descriptive statistics and created histograms to assess the statistical characteristics of the data. To evaluate the congruence between the FSRA and the calculated probability of falling, we plotted FSRA categorizations against probability of falling. Concurrent validity was examined with Spearman's rho (correlation coefficient),32 using the following criteria to interpret levels of agreement:32 ρ=±0.00 to 0.25, little or no relationship; ρ=±0.25 to 0.50, fair relationship; ρ=±0.50 to 0.75, moderate to good relationship; ρ=±0.75, good to excellent relationship.32 We examined the sensitivity and specificity of the Shumway-Cook probability equation1 in our sample. Sensitivity is defined as the ability of a test or measure to detect the target condition (positive test) when the target condition is actually present, and specificity as the ability of a test or measure to correctly identify the absence of the condition (negative test) when the target condition is absent.32 We compared the number of falls reported by our sample with the predicted number of falls in our sample, using a cutoff of 0.5, as described by Shumway-Cook and colleagues.1

RESULTS

Nine men (31%) and 20 women (69%) completed the study. Use of visual aids was common (96% of participants reported using glasses to improve their vision); 27% of participants reported using a hearing aid. Almost three-quarters of participants (72%) reported English as their first language; the remaining 28% reported German as their first language. Additional demographic data are presented in Table 1; Table 2 gives descriptive characteristics of the sample for each measure used in the study. Of 11 participants who reported a fall (MFQ General, Item 1), 5 reported 1 fall, 3 reported 2 falls, and 3 reported >2 falls. BBS scores, EFST scores, MFQ scores, and probability of falling for those who reported falls and for non-fallers are shown in Table 3; 11% of non-fallers (n=2) and 27.3% of fallers reported a history of imbalance.

Table 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample (n=29)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 77.7 (4.0) | 70–85 |

| No. of medications | 2.9 (2.5) | 0–5 |

| No. of falls | 0.9 (1.7) | 0–7 |

| MMSE score | 29.1 (1.1) | 26–30 |

MMSE=Mini-Mental State Exam.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Sample (n=29)

| Measure | Mean (SD) score; range | 95% CI | Possible range of scores for measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBS score | 48.8 (3.5); 39–55 | 47.5–50.1 | 0–56 |

| EFST score | 0.7 (0.8); 0–2 | 0.4–1.1 | 0–5 |

| MFQ score | 2.4 (1.9); 0–6 | 1.9–3.3 | 0–10 |

| Probability of falling | 0.34 (0.04); 0.05–0.78 | 0.25–0.43 | 0.0–1.00 |

BBS=Berg Balance Scale; EFST=Elderly Fall Screening Test; MFQ=Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Non-fallers (n=18) and Fallers (n=11)

| Group; mean (SD); range |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Non-fallers | Fallers |

| BBS score | 47.9 (3.4); 39–54 | 50.2 (3.5); 46–55 |

| EFST score | 0.4 (0.6); 0–2 | 1.3 (0.8); 0–2 |

| MFQ score | 2.3 (2.0); 0–6 | 3.0 (1.8); 0–6 |

| Probability of falling | 0.31 (0.20); 0.05–0.78 | 0.38 (0.30); 0.09–0.74 |

BBS=Berg Balance Scale; EFST=Elderly Fall Screening Test; MFQ=Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire.

Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm fall-risk categorization and probability of falling

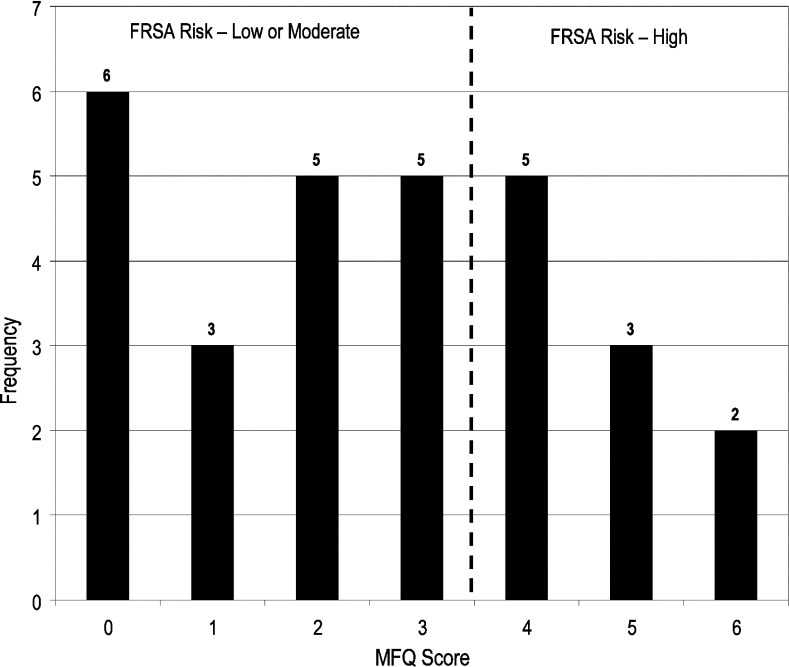

Scores on the EFST ranged from 0 to 2: 13 participants (45%) scored 0, 10 (35%) scored 1, and 6 (20%) scored 2. MFQ scores ranged from 0 to 6, with a median score of 3 (see Figure 1 for distribution of MFQ scores). The FSRA categorized 23 participants (79%) as low fall risk, 4 (14%) as moderate fall risk, and 2 (7%) as high fall risk.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire (MFQ) scores (n=29).

FSRA=Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm

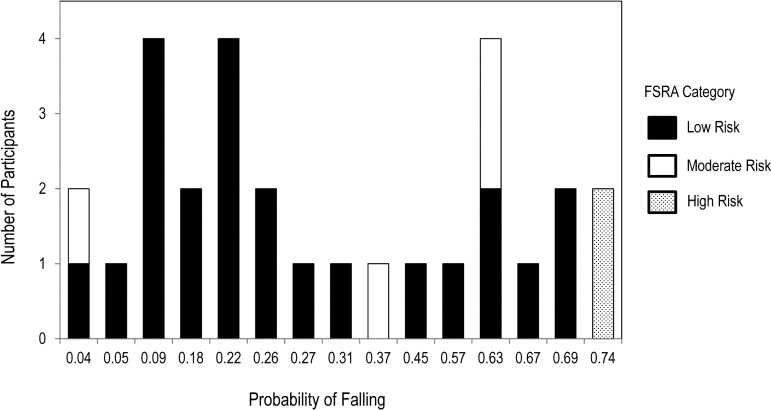

The calculated probability of falling ranged from 0.04 to 0.74 (mean 0.35 [SD 0.25]; 95% CI, 0.25–0.45). For 13 participants (45%), probability of falling ranged from 0 to 0.25; 6 (20%) had a probability of falling ranging from 0.26 to 0.5, and 10 (34%) had a probability of falling ranging from 0.51 to 0.75. Figure 2 plots FSRA categorizations versus calculated probability of falling; 94.4% of non-fallers (17/18) and 100% of fallers (11/11) were correctly classified.

Figure 2.

Falls Screening Referral Algorithm (FSRA) Categorizations of Low, Moderate and High Fall Risk versus the Probability of Falling (n=29).

FSRA=Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm Concurrent validity

The relationship between the FSRA fall-risk categorizations and probability of falling as calculated by Shumway-Cook and colleagues' regression model1 was fair, but not significant (Spearman's ρ=0.35, p=0.06).

DISCUSSION

Accurate fall screening for community-dwelling older adults is a vital first step in developing effective programmes for fall prevention and management, and identification of fall risk has therefore received substantial research attention. Although screening tools with high predictive value for older adults in long-term care and acute-care settings exist,21 a comparable tool for use with community-dwelling older adults remains elusive. Screening tools should have clear written procedures and established thresholds to trigger intervention pathways.18 The FSRA was developed by a group of health care professionals and other community partners to identify fall risk among community-dwelling older adults in the context of a specific provincial health system; it was intended to be administered without specialized equipment, within a reasonable time period, by a variety of health care providers. It is important to ensure the validity of this screening tool, or of any screening tool for fall risk, so that those at high risk for falls are appropriately identified and can subsequently be referred to specific health professionals who can address their individual needs and implement appropriate interventions.

We did not find a significant relationship between probability of falling and FSRA categorization of fall risk. Furthermore, the FSRA tool tended to over-categorize participants into the low-risk category. Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model1 determined that our participants had a wide range of probabilities of falling; our findings suggest that using the EFST as the first step of the algorithm tends to over-categorize individuals into the low-risk pathway. The majority of participants (79%) scored 0 or 1 on the EFST, which automatically places them into the FSRA's low-risk category, but 26% of these participants had a probability of falling ranging from 0.51 to 0.75, which may be more accurately categorized as a moderate or high risk of falling. Of 10 participants who scored >3 on the MFSQ, which would place them in the FSRA's high-risk category, 8 scored <2 on the EFST, and were therefore categorized as low risk by the FSRA; of these, 4 had a calculated probability of falling >0.55. The EFST includes questions about number of previous falls, injuries sustained during these falls, and number of near falls, as well as examining gait performance over 5 m. These EFST components do capture some of the fall risk factors identified in the literature, but the fact that this tool has so few items and so few scoring options likely introduces the potential for ceiling or floor effects and reduces the tool's responsiveness to change. The EFST does not provide a clear definition of a fall or a near fall, does not give a time frame for the near fall item (e.g., within the past 6 months or 1 year), and has undergone very limited psychometric testing. Furthermore, the EFST requires a report of two or more falls to receive a score of 1 for the first question. The EFST may be attempting to distinguish one-time fallers from recurrent fallers, but in an initial screening tool for a fall-risk algorithm, a history of any fall may be significant.

The MFQ component of the FSRA collects information about many of the factors previously established in the literature as important for fall risk and falls: fall history, fall injury history, physical activity levels, dizziness, sensory difficulties, medication usage, current medical conditions, cognitive impairments, environmental hazards, gait impairments, balance impairments, muscle weakness, and arthritis.24 The MFQ appears to include a wide range of fall risk factors, but we found several limitations in its administration. First, the MSQ scoring criteria are not well defined, and we were unable to find sufficient instructions for scoring. The tool consists of 10 factors and a general section, and it is unclear how the items under each factor are to be scored; it was also not known whether the general category should be included in the total score. Second, several items are unclear, either because they lack specifics or because they are compound in nature. For instance, the last item in Factor II (Sensory Problems) asks whether the individual is “unsure of their footing or has trouble walking on uneven ground or inclines”; this wording creates ambiguity, both for interpretation and for scoring, as a person may have trouble walking on uneven surfaces because of balance, joint mobility, or specific gait, yet may still be sure of his or her footing. Many of our study participants were not sure how to answer several of the questions and had to ask for further clarification and assistance. In addition, several questions are repeated across factors. Third, the FSRA defines high-risk individuals as those who have “evidence of risk in greater than three [MFQ] factors, especially in Factors I–V”; such wording introduces subjectivity into the interpretation of the algorithm's scoring system. Finally, the EFST and the MFQ include some similar questions, but participants' responses were not consistent across measures; this may be a result of unclear or ambiguous wording.

The FSRA was initially developed by the SFPC based on an extensive review of the literature and was intended as an easy-to-use screening tool that could be implemented in a variety of settings. As a result of our findings and the weaknesses identified in the present study, discussions are underway among SFPC members about next steps. The MFQ will be revised to eliminate redundancy, clarify wording, and capture the range of potential fall risk factors among community-dwelling older adults. Although the FRSA remains in use, the algorithm will be revised based on our results and taking into consideration the most recently published guidelines for fall prevention.33

LIMITATIONS

Although our sample consisted of older adults with a wide range of probability of fall risk, as determined by the predictive model used, our study is limited by the small sample of convenience—all participants were recruited from the same independent-living seniors' housing complex—which limits the generalizability of the results. A second limitation of this study is the possible misinterpretation of the MFQ administration and scoring criteria. The SFPC Web site does not describe MFQ administration and scoring in detail, and we were not able to find any further information about the MFQ in the literature. We chose to interpret the administration and scoring as a clinician who accessed the FSRA from the SFPC Web site might do. During pilot testing of the study procedures, we did review the MFQ information on the Web site to ensure some level of consistency among evaluators with respect to instructions to participants, administration of the MFQ, data collection, and item endorsement. However, information bias, specifically misclassification bias,34 may nevertheless have been introduced during data collection. We may have classified participants incorrectly into the moderate- or high-risk category if we did not administer the MFQ as intended. In addition, participants had to recall specific information to answer MFQ questions (e.g., previous falls, near falls); this type of information is subject to recall bias34 (i.e., participants may remember events inaccurately), which can lead to underestimation of risk. Although a systematic review found recall methods for falls monitoring to be highly specific (91% to 95%) and sensitive (80% to 89%),35 and self-report methods are considered generally valid,32 some studies have found that older adults do underestimate particular health events.36 In addition, the nature of some topics may influence participants' comfort level or their willingness to disclose particular information.37

An additional potential limitation of this study is the use of a non-equivalent comparator to determine concurrent validity. Because we were unable to identify a comparable “gold standard” measure, we chose Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model of probability of falling,1 after a comprehensive review of the literature. The algorithm and the regression model are similar in intent (i.e., fall risk or probability of falls to determine appropriate referral or intervention pathway) but required us to compare fall risk categories (a discrete variable) to probability of falling (a continuous variable). Although epidemiological studies have found a correlation between a history of falls and future falls,4,6 Shumway-Cook and colleagues used a relatively small cross-sectional sample to develop their probability model, and the model is based on self-reported retrospective fall history and does not predict future falls.1 A prospective methodology for fall data collection is more reliable,38 and prospective and longitudinal studies are considered the methods of choice in falls research.

CONCLUSION

Our study found that the FSRA lacks concurrent validity relative to Shumway-Cook and colleagues' predictive model,1 and it is therefore recommended that the FRSA undergo further refinement and testing. We found that the first step of the FSRA, the EFST, over-categorized participants into low-fall-risk categories; thus, this tool may not be the most appropriate initial screening step for a fall-risk algorithm. The second step of the FSRA, the MFQ, requires revision to enhance clarity and decrease duplication; clear administration and scoring guidelines for the MFQ should also be developed. Future research to further evaluate the validity of the FSRA, and particularly the validity of the EFST component as the first step, is highly recommended. In addition, the impact on overall validity of using a different measure (e.g., the timed up-and-go39) as the first step of the FSRA should be explored.

KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic

Falls and fall-related injuries in older adults significantly affect mobility, quality of life, and mortality and have significant financial consequences for Canada's health care system. Accurate screening for fall risk in older adults is a vital first step in developing appropriate programmes to prevent and manage falls. Although several screening tools are available to identify those at risk of falling in long-term care and acute-care settings, a brief, valid multi-factorial screening tool for community-dwelling adults remains elusive.

What this study adds

The Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium's Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm (FSRA) was developed as a brief, multi-factorial screening tool to identify fall risk categories and subsequent management pathways for community-dwelling older adults. The findings of the present study indicate that the FSRA may not be a valid fall-risk screening tool for community-dwelling older adults and that using the Elderly Fall Screening Test as the first step of the FSRA contributes to this lack of validity.

Appendix 1: Falls Screening and Referral Algorithm

Adapted from Saskatoon Health Region, Programs & Services (Falls Prevention), Saskatoon, SK (http://www.saskatoonhealthregion.ca/pdf/04_Elderly%20Falls%20Screening%20Test.pdf)

Appendix 2: Fall-Risk Screening: Multi-factor Falls Questionnaire22

Reproduced by permission. Note: the documents and algorithm have now been revised based on the findings of our study.

General Questions:

-

□

Have you fallen? If so, how many times?

-

□

Have you experienced a near fall? (e.g. slip, trip, stumble or bumped against a wall?)

-

□

Have you previously reported any falls to a health professional? If so, how many falls?

-

□

Have you ever sought medical attention for a fall?

-

□

If you fell, would you need help to get back up from the ground?

-

□

Have you limited any of your activities or decreased how much you leave your home due to a fall, near fall, or fear of falling?

-

□

Have you ever broken a bone, or have you been diagnosed with osteoporosis?

-

□

If so, are you not currently taking any calcium, vitamin D supplements and/or medications to stimulate bone growth?

-

□

Do you exercise less than 30 minutes a day most days of the week?

FACTOR I—Syncope/Drop Attack/Sudden Unexplained Falls:

-

□

Have you ever fallen because of a sudden, unexpected fainting or blackouts?

FACTOR II—Sensory Problems:

-

□

Do you have vision problems?

-

□

Blurry, not as sharp

-

□

Difficulty seeing to the side or different depths or distances

-

□

Sensitive to light or changing light

-

□

Do you have decreased feeling, numbness or tingling in your feet?

-

□

Are you unsure of your footing or have trouble on uneven ground or inclines?

FACTOR III—Medication Risk:

-

□

Do you take more than 3 prescription medications each day?

-

□

Do you take any medications:

-

□

to help you sleep?

-

□

to help you control your mood (e.g. anxiety, depression)?

-

□

to prevent seizures?

-

□

to control heart rhythm?

-

□

Have there been any recent changes to your medications (e.g. drug/dose that made you feel dizzy or unsteady)?

-

□

Do you have more than one drink of alcohol in a day?

FACTOR IV—Acute or Significant Medical Problems:

-

□

Have you recently had flu-like symptoms or felt unwell at the time of a fall or near fall?

-

□

Do you have health problems that limit your activity?

FACTOR V—Indication of Cognitive Problems:

-

□

Do you notice that you have problems with your memory? (more than normal, more than other people your age do)

-

□

Do family or friends say that you have problems with your memory?

-

□

Do you have trouble completing familiar tasks (get muddled when doing so)? (e.g. writing a cheque, finding your way in a familiar store/mall)

FACTOR VI—Environmental Hazards:

Where have you fallen?

-

□

Inside your home

-

□

Outside your home

-

□

In the community at large

-

□

Have you fallen repeatedly in any one place?

-

□

Were there any hazards in the environment when you fell, that you think contributed to your fall?

-

□

Do you think that a safety check of your home, yard and/or neighbourhood would assist you to avoid future falls?

FACTOR VII—Gait/Mobility Problems:

-

□

Do you sometimes feel unsteady when you walk?

-

□

Do you think your walking method puts you at risk for falling?

-

□

Do you choose not to use a gait aid even though people tell you it is safer?

-

□

Do you have problems or concerns getting in/out of bed, chair, tub or toilet?

FACTOR VIII—Balance Problems:

-

□

Do you feel that you have decreased balance?

-

□

Do you sometimes feel off-balance, dizzy or unsteady when you walk?

FACTOR IX—Endurance Problems/Weakness:

-

□

Do you feel you have leg weakness or that you tire easily when you walk?

FACTOR X—Pain/Joint Problems:

-

□

Do you have any sore joints or arthritis?

-

□

Is your hand activity limited by pain?

Physiotherapy Canada 2013; 65(1);31–39; doi:10.3138/ptc.2011-17

References

- 1.Shumway-Cook A, Baldwin ML, Polissar NL, et al. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults. Phys Ther. 1997;77(8):812–9. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.8.812. Medline:9256869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shumway-Cook A, Ciol MA, Hoffman J, et al. Falls in the Medicare population: incidence, associated factors, and impact on health care. Phys Ther. 2009;89(4):324–32. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070107. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20070107. Medline:19228831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SMARTRISK. The economic burden of unintentional injury in Canada [Internet] Ottawa: Health Canada; 1998. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.smartrisk.ca/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. Medline:3205267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1050–6. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.24893. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2001.24893. Medline:11494184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Loughlin JL, Robitaille Y, Boivin JF, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for falls and injurious falls among the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(3):342–54. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116681. Medline:8452142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott V, Pearce M, Pengelly C. Technical report: injury resulting from falls among Canadians age 65 and over on the analysis of data from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2005. [updated 2009 Oct 1; cited 2012 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/seniors-aines/publications/pro/injury-blessure/falls-chutes/tech/injury-blessures-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hornbrook MC, Stevens VJ, Wingfield DJ, et al. Preventing falls among community-dwelling older persons: results from a randomized trial. Gerontologist. 1994;34(1):16–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.1.16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/34.1.16. Medline:8150304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens JA, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ, et al. Self-reported falls and fall-related injuries among persons aged ≥65 years—United States, 2006. JAMA. 2008;229(14):1658–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.05.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.14.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on seniors' falls in Canada. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2005. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/seniors-aines/publications/pro/injury-blessure/falls-chutes/index-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Ontario trauma registry bulletin: comparisons of trauma hospitalizations across Canada, 1998/99. Toronto: The Institute; 2001. [cited 2010 Mar 30]. Available from: http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/301/statcan/portrait_of_seniors-e/89-519-XIE2006001.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Canada. A portrait of seniors in Canada (Catalogue no. 89-519-XIE) Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2006. [cited 2012 May 23]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-519-x/89-519-x2006001-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safe Saskatchewan; Seniors' Falls Provincial Steering Committee. A five-year strategic framework (2008–2013) towards a vision of seniors living fall free lives. Regina: Safe Saskatchewan; 2007. [updated 2007 Dec; cited 2010 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.safesask.com/images/File/Seniors_Falls_Strategic_Framework_Jan_2008(2).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.King MB, Tinetti ME. Falls in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(10):1146–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07017.x. Medline:7560708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conradsson M, Lundin-Olsson L, Lindelöf N, et al. Berg Balance Scale: intrarater test-retest reliability among older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilities. Phys Ther. 2007;87(9):1155–63. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060343. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060343. Medline:17636155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, et al. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122–30. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh017. Medline:14960426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, et al. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1049. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1049. Medline:9366729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perell KL, Nelson A, Goldman RL, et al. Fall risk assessment measures: an analytic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(12):M761–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.12.m761. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.12.M761. Medline:11723150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming KC, Evans JM, Weber DC, et al. Practical functional assessment of elderly persons: a primary-care approach. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70(9):890–910. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63949-9. Medline:7643645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gates S, Smith LA, Fisher JD, et al. Systematic review of accuracy of screening instruments for predicting fall risk among independently living older adults. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(8):1105–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2008.04.0057. Medline:19235113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, et al. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl165. Medline:17293604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamb SE, McCabe C, Becker C, et al. The optimal sequence and selection of screening test items to predict fall risk in older disabled women: the Women's Health and Aging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(10):1082–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1082. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/63.10.1082. Medline:18948559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muir SW, Berg K, Chesworth B, et al. Application of a fall screening algorithm stratified fall risk but missed preventive opportunities in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2010;33(4):165–72. Medline:21717920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saskatoon Health Region. Programs and services injury prevention: falls prevention screening tools. Saskatoon: The Health Region; 2012. [cited 2009 Jun 6]. Available from: http://www.saskatoonhealthregion.ca/your_health/ps_ip_falls_screening_tools_related_documents.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cwikel JG, Fried AV, Biderman A, et al. Validation of a fall-risk screening test, the Elderly Fall Screening Test (EFST), for community-dwelling elderly. Disabil Rehabil. 1998;20(5):161–7. doi: 10.3109/09638289809166077. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09638289809166077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domholdt E. Rehabilitation research: principles and applications. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. Medline:1202204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, et al. Measuring balance in the elderly: preliminary development of an instrument. Physiother Can. 1989;41(6):304–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.41.6.304. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, et al. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83(Suppl 2):S7–11. Medline:1468055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg KO, Maki BE, Williams JI, et al. Clinical and laboratory measures of postural balance in an elderly population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73(11):1073–80. Medline:1444775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogle Thorbahn LD, Newton RA. Use of the Berg Balance Test to predict falls in elderly persons. Phys Ther. 1996;76(6):576–83. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.6.576. discussion 584–5. Medline:8650273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):148–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x. Medline:21226685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32(1-2):51–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2. Medline:447779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganz DA, Higashi T, Rubenstein LZ. Monitoring falls in cohort studies of community-dwelling older people: effect of the recall interval. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2190–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00509.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00509.x. Medline:16398908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinoff G, Ore L. The Barthel Activities of Daily Living index: self-reporting versus actual performance in the old-old (> or=75 years) J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(7):832–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01510.x. Medline:9215334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hauer K, Lamb SE, Jorstad EC, et al. PROFANE-Group. Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age Ageing. 2006;35(1):5–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afi218. Medline:16364930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilian C, Salmoni A, Ward-Griffin C, et al. Perceiving falls within a family context: a focused ethnographic approach. Can J Aging. 2008;27(4):331–45. doi: 10.3138/cja.27.4.331. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cja.27.4.331. Medline:19416795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. Medline:1991946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]