ABSTRACT

Purpose: The Safe Functional Motion test (SFM) was developed to measure observed body mechanics and functional motion associated with spine load, balance, strength, and flexibility during everyday tasks to profile modifiable risks for osteoporotic fracture. This cross-sectional study evaluated the associations between SFM score and history of vertebral compression fracture (VCF), hip fracture, and injurious falls, all established predictors of future risk. Method: An osteoporosis clinic database was queried for adults with an initial SFM score and corresponding data for prevalent VCF and/or hip fracture, femoral neck bone mineral density (fnBMD), and history of injurious fall (n=847). Multiple logistic regressions, adjusted for age, gender, and fnBMD (and injurious falls in the prevalent fracture analyses), were used to determine whether associations exist between SFM score and prevalent VCF, prevalent hip fracture, and history of injurious fall. Results: SFM score was associated with prevalent VCF (odds ratio [OR]=0.89; 95% CI, 0.79–0.99; p=0.036), prevalent hip fracture (OR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.65–0.92; p=0.004), and history of injurious fall (OR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.70–0.93; p=0.003) after adjusting for other important covariates. Conclusions: Adults with higher SFM scores (“safer motion” during performance of everyday tasks) were less likely to have a history of fracture or injurious fall. Further study is warranted to evaluate the predictive value of this tool.

Key Words: activities of daily living, compression fractures, hip fractures, musculoskeletal system, osteoporosis, risk assessment

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Le test fonctionnel de mouvement (Safe Functional Motion test, SFM) a été créé pour mesurer les mécanismes corporels et le mouvement fonctionnel associés à la sollicitation de la colonne vertébrale, à l'équilibre, à la force et à la souplesse au cours des activités quotidiennes, afin d'établir un profil des risques modifiables de fracture ostéoporotique. Cette étude transversale a évalué les associations entre les pointages obtenus au SFM et l'historique de fractures de compression vertébrale (FCV), de fracture de la hanche et de chutes préjudiciables qui sont autant de signes avant-coureurs confirmés de risques futurs. Méthode : Une recherche a été effectuée dans la base de données d'une clinique de l'ostéoporose afin de répertorier des adultes dont les résultats initiaux au SFM de départ, les données correspondantes et la densité minérale osseuse du col du fémur (DMOcf) prédisposaient à une FCV ou à une fracture de la hanche, ou qui possédaient des antécédents de chute préjudiciable (n=847). De multiples régressions logistiques, adaptées en fonction de l'âge, du sexe et de la DMOcf (et des chutes préjudiciables de l'analyse des risques de fractures) ont été utilisées pour déterminer si les associations entre les résultats du SFM et la prévalence des FCV, des fractures à la hanche et des chutes préjudiciables existent effectivement. Résultats : Les résultats du SFM ont été associés avec des FCV prévalentes (risque relatif approché [RRA]=0,89; 95 % d'IC, 0,79–0,99; p=0,036), des fractures de la hanche prévalentes (RRA=0,77; 95 % d'IC, 0,65–0,92; p=0,004) et des antécédents de chute préjudiciable (RRA=0,80; 95 % d'IC, 0,70–0,93; p=0,003) après ajustement d'autres covariables importantes. Conclusions : Les adultes dont les résultats au SFM étaient plus élevés (« mouvements sûrs » au cours de l'exécution de tâches courantes) couraient moins de risques d'afficher des antécédents de fracture ou de chute préjudiciables. D'autres études seront nécessaires pour évaluer la valeur prévisionnelle de cet outil.

Mots clés : évaluation des risques, fracture de compression, fracture de la hanche, ostéoporose, système musculosquelettique

Current assessments aimed at preventing fragility fracture include testing bone mineral density (BMD) and profiling historical risk factors, but few examine fall risk and none evaluates habitual biomechanics or movement strategies.1–3 Emerging evidence suggests that low BMD accompanied by changes in postural alignment or suboptimal movement strategies can lead to spine loads exceeding fracture threshold.4,5 Movement strategies thought to elevate load on weakened vertebrae to unsafe levels include slumped posture, bending from the waist, strained twisting at the spine, reaching too far, and combinations of these motions.6 Task-oriented compensatory strategies for dealing with deficits in flexibility, muscle strength, and/or neuromuscular control may increase the frequency and magnitude of spine loading behaviours:4,7 for example, if squatting is prohibited by lower-body muscle weakness or reduced flexibility, a person may bend from the waist to pick up an item on the floor. Loads on the spine during this kind of daily activity can exceed fracture threshold.5 It is critical, therefore, to examine physical performance in older adults with bone loss using measures that capture how changes in spine load interact with changes in balance, strength, and/or flexibility that may occur with altered movement strategies.

Numerous studies report impaired physical performance following injurious falls and fracture.8–10 Cross-sectional analyses have found that individuals with prior fracture have poorer performance in gait speed, sit-to-stand, and balance tests.11,12 It is not clear whether physical performance impairment is a consequence of fracture or a predisposing factor.8,9,13 The Safe Functional Motion test (SFM) is a performance-based tool developed by clinicians to evaluate body mechanics and functional motion during a sample set of tasks in people at risk for fragility fracture.14 The SFM's tasks and constructs (balance, upper-body flexibility, upper-body strength, lower-body flexibility, lower-body strength) are similar to other performance-based tools such as the Continuous-Scale Physical Functional Performance (CS-PFP) and the Physical Performance Test (PPT).14–16 Whereas these tools score physical performance of multiple standardized tasks in terms of time to complete, weight lifted, and/or distance covered, SFM scores reflect body mechanics and movement strategies used in daily life that may be compensating for poor balance, lack of flexibility, and/or muscle weakness and which may place excessive loads on a vulnerable osteoporotic spine.14 The SFM consists of 10 tasks; nine of these tasks closely represent typical daily activities, while a tenth “emergency task” assesses visual and vestibular contributions to balance.14 The “typical daily activities” tasks are (1) pouring water into a glass, (2) taking off and putting on shoes and socks, (3) picking up a newspaper, (4) reaching into an overhead cupboard with both hands to place and remove a container of known weight, (5) sweeping, (6) loading and unloading a top-loading washing machine, (7) loading and unloading a front-loading dryer, (8) sitting on the floor with legs stretched out in front, and (9) carrying weighted bags (to simulate groceries) while walking, climbing stairs, and walking while looking side to side. The “emergency task” involves moving and standing on compliant and non-compliant surfaces with eyes open and eyes closed. The SFM uses domain-weighted scoring: 60% of the total score is determined from scores for the spine loading and balance domains, and 40% from scores on the upper- and lower-body flexibility domains and the upper- and lower-body strength domains. Thus, the total score preferentially reflects aspects of movement most pertinent to individuals with known fracture risk.

The tester is trained and credentialed to administer and score the SFM in a standardized manner; the tester describes each task, and people are asked to move in the way they normally do at home to perform that task. Only the “emergency task” involves a practice trial. All other tasks are either routinely performed and/or familiar to the person, or are not part of the person's role (and, therefore, are not assessed because habitual movement patterns have not been developed). See Box 1 for the instructions given at the start of the SFM; specific instructions, equipment, and abbreviated scoring criteria for three of the tasks are presented in Appendix 1 (available online).

Box 1. Standardized verbal instructions given to participants at the start of the Safe Functional Motion test.

You will be wearing this belt throughout the test for your safety. [Tester secures gait/transfer belt on the examinee.] Now you will be completing 10 tasks that closely represent typical movement patterns in which you engage daily. I will be watching how you complete each of the 10 tasks. Please complete each task as you would at your home. If you need assistance during any task, please let me know and I will assist you. You may request a rest break at any time during the testing process. I will accompany you throughout the testing process and give you specific directions for each task. Please tell me if you do not understand the directions or would like them to be repeated. Also, if you have not completed the body movements involved in any of the tasks I describe within the last 6 months please let me know. You may elect to perform, but will not be expected to perform, any task you have not done in the last 6 months. Do you have any problems that we have not talked about?

Multiple movement strategies may be used to accomplish a given task, but measurement studies abstracted in meeting proceedings to date suggest that the SFM provides a valid and reliable measure of the movement patterns used.17–20 Test–retest reliability of the SFM, determined in 29 older adults recruited through a specialty osteoporosis clinic in northeast Georgia and assessed on two occasions (separated by 3–7 days) by the same credentialed tester, demonstrate that the tasks and scoring are performed consistently (ICC=0.89, standard error of measurement=2.00 points).17 The expected associations between SFM total scores and PPT total scores were observed (r=0.56) for 31 older adults recruited through the same clinical site, despite differences in the number of test items and differences in the scoring (SFM measures patterns of movement and considers spine loading, whereas the PPT measures speed of movement).17 In 30 older adults (27 women) recruited through the same site, the combined SFM scores for upper- and lower-body flexibility and strength were associated with clinical measures of range of motion (measured using goniometry, r=0.58) and strength (measured using Manual Muscle Testing, r=0.42, and grip dynamometry, r=0.38). The composite scores for body flexibility and strength were also associated with mobility (measured using the timed up-and-go test (TUG), r=−0.58 and −0.73, respectively).18 A group of 325 older adults attending the clinic volunteered to complete the Sensory Organization Test (SOT) using computerized dynamic posturography in addition to the SFM, and the two scores were associated (r=0.62).19 Of the 68% assessed who lost points on the SFM balance domain, 77% had at least one sensory variable identified on the SOT; the most common were centre of gravity misalignment (in 54%) and vestibular deficits (in 48%).20 These preliminary reports of reliability and validity were supported in an independently published study of 36 older adults recruited through an osteoporosis specialty clinic in Canada, in that balance domain scores on the short form of the SFM (which did not include the sweeping, washer, or dryer tasks) have the expected associations with TUG, Berg Balance Scale, and Community Balance and Mobility Scale scores (r=−0.69, 0.76, and 0.82, respectively).21 Habitual body mechanics adopted to compensate for deficits in balance ability, strength, and/or flexibility could increase fracture risk. However, the associations between SFM scores and elevated risk of fragility fracture and falls (known to be predicted by histories of fragility fracture and falls) have not been investigated. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to evaluate associations between SFM score and prevalent vertebral compression fracture (VCF), prevalent hip fracture, and history of injurious fall.

METHODS

Study design, procedures, and participants

Our study was a retrospective chart review of adults who attended an osteoporosis specialty clinic in northeast Georgia between December 2004 and March 2009 for initial assessment. Charts were identified by querying the clinic's database registry. Both men and women were included if they had baseline data for SFM and all outcomes (prevalent VCF, prevalent hip fracture, and history of injurious fall within the past year recorded) and covariates of interest (age, gender, femoral neck bone mineral density [fnBMD] within 6 months of baseline SFM test date). All data were de-identified as part of the query process.

Everyone who attends the specialty clinic is asked to read the Health Information Privacy Act Advisory notice and provide written informed consent to allow de-identified data to be entered into the clinic database registry and used for research and quality improvement. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Bone mineral density

Left fnBMD (g/cm2), or right fnBMD if the left hip could not yield accurate results, was determined using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; GE Lunar Prodigy/Advance scanner #41310) within 6 months of the initial SFM test. Certified radiology technicians performed all DXA testing on site, according to the standardized protocol recommended by the manufacturer, and performed quality-assurance scans to confirm stable calibration over time. We chose fnBMD over total femur BMD because initially only fnBMD was entered in the database; hip BMD is preferable to spine BMD for exploring associations, both because of the potential for artefacts in spinal scans and because variability in site measurement is required if a fracture is present in the region of interest.

Age, gender, fracture history, and fall history

Self-reported age, gender, history of non-vertebral fragility fracture, and history of injurious fall were documented. With the exception of VCF and hip fractures, which were confirmed by X-rays taken at the initial visit, all fragility fractures were recorded based on self-report only. A prevalent fracture was recorded if sustained under low-trauma conditions at any time before the baseline SFM test date; fractures of the fingers, toes, clavicle, scapulae, and/or skull were not recorded. A fall with injury was recorded if the person reported an “unexpected loss of balance resulting in coming to rest on the floor, ground or an object below knee level”22(p.198) that caused an injury, as documented in their medical records (e.g., fracture, concussion, sprain), within 1 year before the baseline SFM.

Safe Functional Motion Test (SFM)

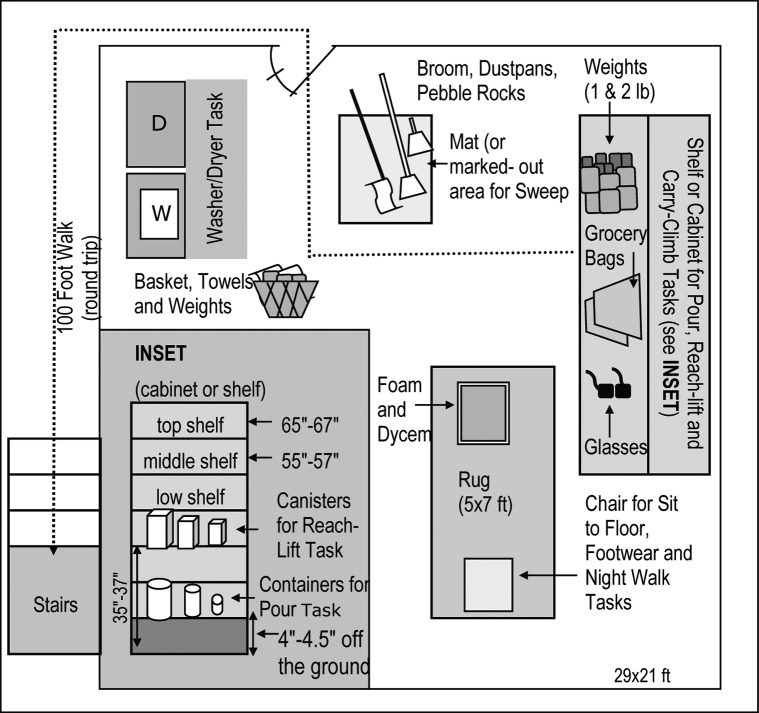

A credentialed tester administered and scored the SFM according to the standardized testing procedures. Items used to complete the tasks were arranged in a standard pattern according to the testing protocol, as shown in Figure 1; additional adaptive aids (e.g., step stool, reacher, long-handled shoehorn) that may be used to perform the task at home were available for use. For safety, a transfer belt was worn around the waist for the duration of testing, and the maximum weight lifted during any single task was limited to 4.54 kg.6 Any task the participant had not completed at home in the past 6 months due to a recent change in health condition, or which had never been a role within the lifetime of the participant, was not performed; the purpose of the SFM is to evaluate habitual movement patterns that may elevate the risk of fracture or falls, not to impose additional risk by asking people to complete movement tasks that are not part of their life routine. The tester asked the person to complete each task in the same way that he or she would normally do so at home and scored the observed performance. Completion time for the SFM was approximately 20–30 minutes. Any adverse events (injuries requiring medical follow-up) attributable to performance of the SFM were documented, and individuals were asked to rate symptoms of pain and dizziness immediately before and after completing the SFM on a 10 cm pain algometer.

Figure 1.

Set-up of tasks performed during the Safe Functional Motion test, including equipment used (illustration only; not to scale).

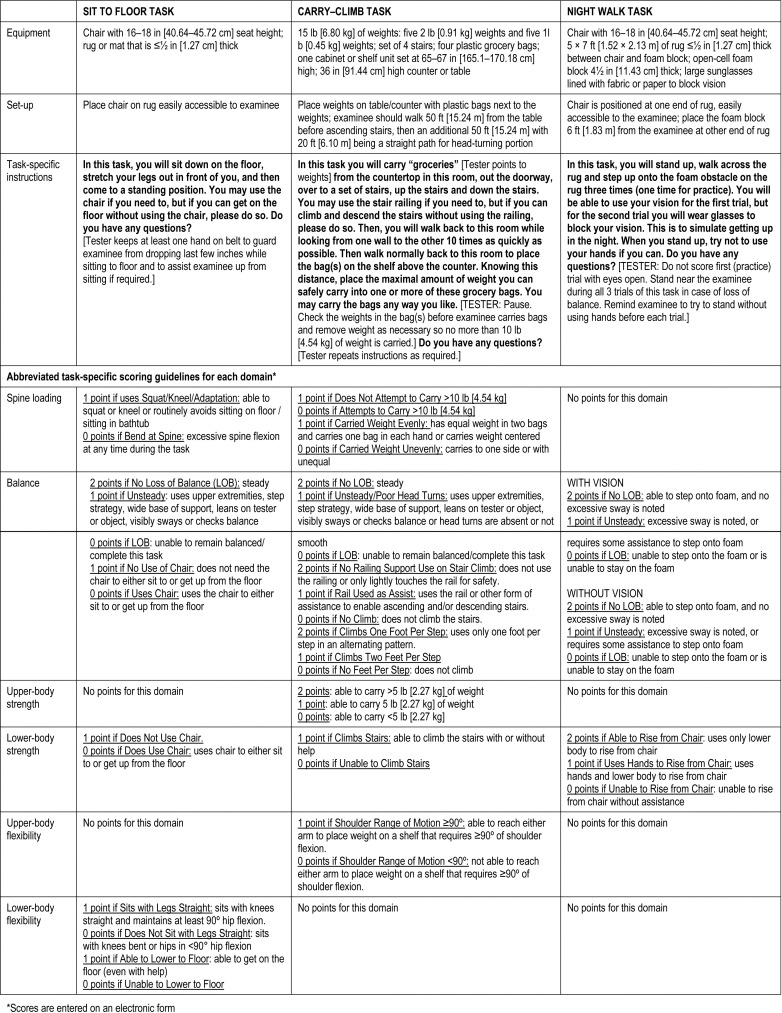

Table 1 summarizes the domain-weighted scoring across the six domains as a function of each task. (Detailed criteria associated with scoring the various domains applicable to the climb-carry, sit to floor, and emergency tasks are provided in Appendix 1 for illustration.) No points are lost when people avoid unsafe spine motions by altering the motion, using adaptive equipment (such as a reacher), asking for assistance, or stating that they avoid the task. If a person routinely uses external supports such as assistive devices and mobility aids to perform a task, this requirement is noted; the score reflects his or her ability to use safe movements while manipulating the aid. For example, using a reacher to pick up a newspaper may result in full points for both spine loading and balance domains if the person avoids bending the spine and maintains balance while using the device. The points for task components are summed and divided by all possible points to calculate the percentage score (SFM score) from 0 to 100 (0=unsafe, impaired functional motion; 100=safe, optimal functional motion).

Table 1.

Safe Functional Motion Test (SFM) Scores for Each Task Contributing to Each of Six Physical Performance Domains

| Score by physical performance domain |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFM Task | Spine loading | Balance | UB strength | LB strength | UB flexibility | LB flexibility |

| Pour* | 3 | 4 | 2 | – | – | – |

| Footwear | 1 | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Newspaper | 1 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| Reach–lift | 1 | 2 | 2 | – | 1 | – |

| Sweep* | 1 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| Washer* | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| Dryer* | 2 | – | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Sit to floor | 1 | 3 | – | 1 | – | 2 |

| Carry–climb | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Night-walk | – | 4 | – | 2 | – | – |

| Maximum possible points† | 13 | 23 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

Not included in the SFM–short form.

If task is not a role for the person or has not been performed in the past 6 months, points for this task are removed from the denominator. The total SFM score is calculated as a percentage of maximum points that could be achieved given the number of tasks performed within each domain; 100% represents optimal “safe” motion during performance of all tasks.

UB=upper body; LB=lower body.

Statistical analyses

Using univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses, we examined associations between SFM score and (a) prevalent VCF, (b) prevalent hip fracture, and (c) recent falls with injury. All three models for multiple logistic regression analyses were constructed to include known predictors and control for potential confounders.

Participants with no VCF or hip fractures were expected a priori to have higher SFM scores than those who had a VCF or hip fracture. In addition to SFM score, other known predictors of fracture and potential confounders (age, gender, fnBMD, history of injurious fall) were included in the multiple logistic regression model to determine the odds ratios (ORs) for prevalent VCF and for prevalent hip fracture. Likewise, participants with no history of injurious fall within the past year were expected a priori to have higher SFM scores. In addition to SFM score, other known predictors of falls and potential confounders (age and gender) were included in the multiple logistic regression model for determining the OR for prevalent falls with injury.

Each logistic regression analysis was constructed to model the occurrence of an event (history of ≥1 VCF/hip fracture or injurious fall as applicable). Age, fnBMD, and SFM score were entered as continuous data; gender and history of injurious fall were entered as categorical variables, with “Female” and “No injurious falls,” respectively, as the reference categories. For meaningful presentation, we report the ORs using a 10-year unit for age, a 10-point unit for SFM score, and a 0.10 g/cm2 unit for fnBMD. We assessed each model's goodness of fit using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test; p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

During the study period, 1,627 adults presented to the clinic for an initial SFM test, of whom 847 had data available on all outcomes and covariates of interest and were therefore included in the statistical analyses. Most participants included in the analyses were women (89.7%), and nearly all described themselves as Caucasian (98.6%). Mean age was 68.2 (SD 11.0) years, mean fnBMD was 0.76 (SD 0.13) g/cm2, and mean SFM score was 77.0 (SD 15.1); 29.9% of participants presented with prevalent VCF, 4.6% presented with prevalent hip fracture, and 10.6% reported a fall with injury within the year before testing. No adverse events occurred as a result of performing the SFM.

Adults not included in the statistical analysis because they had no BMD data within 6 months from SFM testing and/or were missing data on history of injurious fall (n=780) were similar in gender, race, and age to those included in the statistical analyses (91% women; 98% self-described as Caucasian; mean age of 70 [SD 11] y); they had a mean SFM score of 69.5 (SD 17), 36.7% presented with a prevalent VCF, and 4.7% presented with a prevalent hip fracture. As adjunct analyses, we performed logistic regression analyses using the available covariates of age, gender, and SFM score on both prevalent VCF and prevalent hip fracture; results were similar to those obtained in the main analyses (data not shown).

SFM score and VCF

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, SFM score was significantly associated with prevalent VCF (OR=0.78, p<0.001). To reduce the bias that can occur in a non-randomized observational study, we included age, gender, and fnBMD (known risk factors for vertebral fractures), as well as history of injurious fall, as covariates in the multiple logistic regression model. SFM score was significantly associated with prevalent VCF in this covariate adjusted model (Table 2). Participants with higher SFM scores (“safer motion”) were less likely to present with VCF than participants with lower SFM scores (OR=0.89 for each 10-point increase in SFM score; p=0.036). Age, gender, and fnBMD were also significantly associated with VCFs (Table 2). Older participants were significantly more likely than younger participants to present with VCFs (OR=1.31 for every 10 year increase in age; p=0.001). The odds of having a prevalent VCF were more than twice as high for men as for women (OR=2.37; p<0.001). Participants with higher fnBMD scores were less likely than those with lower fnBMD values to present with VCF (OR=0.73 for each 0.10g/cm2 increase in fnBMD; p<0.001). Having had an injurious fall within the past year was not significantly associated with VCF.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Models Analyzing the Relationship between Safe Functional Motion Test (SFM) Scores and Prevalence of Vertebral Fracture, Hip Fracture, and Injurious Falls

| Logistic regression model | Coefficient (β) | SE | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of vertebral fracture* | ||||

| Age | 0.027 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 1.308† (1.109–1.543) |

| Sex (M vs. F) | 0.863 | 0.248 | <0.001 | 2.370 (1.457–3.855) |

| fnBMD | −3.160 | 0.679 | <0.001 | 0.729‡ (0.638–0.833) |

| Injurious fall (Y vs. N) | 0.239 | 0.247 | 0.333 | 1.270 (0.783–2.061) |

| SFM score | −0.012 | 0.006 | 0.036 | 0.887§ (0.794–0.992) |

| Prevalence of hip fracture¶ | ||||

| fnBMD | −6.738 | 1.536 | <0.001 | 0.510‡ (0.377–0.689) |

| Injurious fall (Y vs. N) | 0.973 | 0.424 | 0.022 | 2.647 (1.153–6.080) |

| SFM score | −0.026 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.774§ (0.650–0.922) |

| Prevalence of injurious falls** | ||||

| Age | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.607 | 1.060† (0.848–1.325) |

| Sex (M vs. F) | 0.412 | 0.328 | 0.209 | 1.510 (0.794–2.870) |

| SFM Score | −0.022 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.802 (0.695–0.926) |

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2=13.26, p=0.103.

OR reported is for each 10-y increase in age.

OR reported is for each 0.10 g/cm2 increase in fnBMD.

OR reported is for each 10-pt increase in SFM score.

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2=8.556, p=0.381. Gender not included because the sample included no men with prevalent hip fracture. Age not included due to lack of model fit (Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit p=0.01). With Age included, SFM p=0.025; Age p=0.393.

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2=6.735, p=0.566.

OR=odds ratio; M=male; F=female; fnBMD=femoral neck bone mineral density; Y=yes; N=no; SFM=Safe Functional Motion test.

SFM score and hip fractures

Similarly, SFM score was significantly associated with hip-fracture prevalence in both a univariate logistic regression (OR=0.68; p<0.001) and a multiple logistic regression analysis adjusted for the covariates fnBMD and history of injurious fall (see Table 2). In the covariate-adjusted model, participants with higher SFM scores (“safer motion”) were less likely than those with lower SFM scores to present with a hip fracture (OR=0.77 for each 10-point increase in SFM score; p=0.004). As expected, participants with higher fnBMD values were less likely than those with lower fnBMD values to present with hip fracture (OR=0.51 for every 0.10 g/cm2 increase in fnBMD; p<0.001). Participants who reported an injurious fall were more likely than those who did not to present with a hip fracture (OR=2.65; p=0.022). Because our sample included no men with prevalent hip fracture, we could not include gender as a covariate in the logistic regression model. Although age was significantly associated with prevalent hip fracture in a univariate analysis (with older participants having greater odds of fracture), it was not a significant factor in the multiple regression model (p=0.39). Attempts to keep age as a factor resulted in poor model fit (Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit p=0.018); therefore, age was not included in the final model.

SFM score and falls with injury

SFM score was significantly associated with prevalent injurious falls in both univariate analysis (OR=0.79; p<0.001) and multiple logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and gender (Table 2). In the covariate-adjusted model, participants with higher SFM scores (“safer motion”) were less likely than participants with lower SFM scores to present with a fall with injury (OR=0.80 for each 10-point increase in SFM score; p=0.003). A univariate logistic regression revealed no significant difference between men and women in history of injurious fall, and gender also was not a significant factor in the multiple logistic regression model (p=0.21). Although age was a significant factor in a univariate analysis (older participants were more likely to have experienced an injurious fall), it was not a significant factor in the multiple regression model (p=0.61).

DISCUSSION

Validity of the SFM test was evaluated by examining the association between SFM scores and (a) prevalent VCF, (b) prevalent hip fracture, and (c) recent history of injurious fall. It is known that BMD, age, gender, and history of falls are predictors of fracture and that neuromuscular control declines with age; therefore, we included these factors in the logistic regression models. After adjustment for covariates, the odds of having a VCF, hip fracture, or injurious fall decreased by 11%, 23%, and 20%, respectively, for each 10-point increase in SFM score. Given the observed significant associations with prevalent fractures and injurious falls and the absence of adverse events, the performance-based SFM, with its multiple components, may be a useful adjunct to BMD and fracture risk profiling measures to improve prediction of those most at risk for fragility fracture. Notably, the presence of VCF, confirmed on X-ray in the current study, was associated with SFM score. This type of fragility fracture often goes undetected clinically but has significant negative personal consequences with respect to symptoms and quality of life; if our results can be generalized to adults assessed in non-specialty clinics, SFM scores could help clinicians identify those who might benefit from follow-up investigation with lateral spine X-rays to identify clinically silent vertebral fractures. However, longitudinal studies are needed to establish the relationships between SFM score and both incident fracture and injurious falls.

Most physical performance measures use speed or time, not movement quality, as units of measurement, and they often do not provide an integrated assessment of the multiple factors that influence fracture risk (balance, strength, and spine loading) during typical daily tasks.9–11,23–26 The SFM includes task components that challenge the sensory and musculoskeletal systems in various ways so as to reveal any impairments (e.g., deficits in vision, vestibular input, extremity flexibility, and muscle strength) that may affect the balance system and warrant further investigation, remediation, and/or adaptations. The SFM is unique in enabling qualitative observation of altered movement strategies, which may provide additional information about fracture risk. Fracture risk associated with physical performance levels has been evaluated prospectively using gait speed24 and the TUG.26 In a study by Dargent-Molina and colleagues, gait speed was comparable to fnBMD, age, and heel ultrasound transmission measures for identifying elderly women at high risk of hip fracture.24 Zhu and colleagues found that compared to older women with a normal TUG score, those who took ≥10.2 seconds to complete the TUG had significantly higher rates of incident non-vertebral fracture (21.2% vs. 15.7%), including hip fractures (9.2% vs. 5.3%), but the rate of incident VCF did not differ (5.7% vs. 6.1%).26 It is not clear why the TUG did not identify those at risk for VCF. It may be that the TUG can detect balance impairment and fall risk but not the spine loading that puts osteoporotic vertebrae at risk for fracture. In keeping with the observations from prospective studies, our study demonstrates that history of injurious fall is not related to prevalent VCF but is related to prevalent hip fracture. Interestingly, the SFM score adds value beyond history of injurious fall with respect to prevalent hip fracture and is also associated with VCF. We can infer that balance impairment is more likely to be related to non-vertebral fractures, such as hip fractures, than to VCF and that spine biomechanics and patterns of habitual loading are more strongly related to VCF than to non-vertebral fractures. A prospective study comparing the associations between scores on gait speed, TUG, and SFM and incident vertebral and non-vertebral fractures is needed to confirm the proposed relationship between these measures of physical performance and fracture risk.

The SFM is administered to people with low BMD who attend our specialty osteoporosis clinic. People attending this clinic are identified as having an increased risk of fracture based on factors such as clinical history, BMD, and functional status. Several steps are incorporated into the SFM test to ensure both validity and safety. Testers must be trained and credentialed before administering the SFM; to be credentialed, a tester must achieve a level of agreement of ≥0.85 between his or her scores and those of an experienced tester. The maximum weight a person is allowed to lift while performing any one task is 4.54 kg. A transfer belt is applied, and performance is closely supervised by the tester. Only tasks routinely performed at home in the recent past are tested, and any adaptive strategies or equipment routinely used to complete the task are incorporated into the test. Sound clinical judgment is required when administering the SFM to ensure that any necessary medical precautions are observed; for example, any contraindicated movements or loading are avoided in those who present with unhealed osteoporotic fractures or vertebral augmentation. To date, approximately 7,000 SFM tests have been completed by more than 3,500 people attending the clinic, and no injury has been attributed to the test. While the SFM provides information about physical function, it is important to note that it remains under development and that the extent to which SFM scores predict osteoporotic fracture is not yet established.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limitations. From our cross-sectional study design, we cannot determine either the degree to which physical performance impairments are the sequelae of physical changes associated with falls or fracture, or predispose to falls or fracture, or the predictive validity of the SFM. Moreover, this design makes it difficult to distinguish more recent fractures from older fractures. The presence of prevalent fractures was confirmed using X-ray, but the falls outcome (injurious fall within the past year) relied entirely on self-report. Recall bias creates difficulties in collecting data on falls, even when recording injurious falls documented in the medical record; it is possible that misclassification of participants with undocumented injuries due to falls in the previous year and exclusion of those who fell but did not sustain an injury attenuated the association between history of injurious fall and prevalent spine and hip fractures. Finally, most participants in this study (and most attending the specialty osteoporosis clinic) were Caucasian and had known fracture risk(s) that instigated referral to osteoporosis specialists. Further study is needed to confirm whether these findings can be generalized to the general population and/or to people attending other osteoporosis clinics.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, the SFM is the only measure that quantifies biomechanics of functional motions in conjunction with balance, strength, and flexibility observed during performance of habitual daily activities. Impaired physical performance as measured by the SFM is associated with prevalent fractures of the spine and hip and with a history of injurious falls in adults attending an osteoporosis specialty clinic. Although the temporal nature of these relationships is not known, our data suggest that the SFM may be a useful multi-factorial assessment of an individual's functional risk of fracture and injurious falls and that prospective studies are warranted to determine the predictive validity of the SFM.

KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic

Current assessments aimed at preventing fragility fracture include testing bone mineral density and profiling clinical risk factors such as prior steroid use, gender, and fracture history. Emerging evidence suggests that habitual body mechanics adopted to compensate for deficits in balance ability, strength, and/or flexibility may increase fracture risk, but most physical performance measures use speed or time, not movement quality, as the unit of measurement. Moreover, the key domains of balance and spine loading associated with body mechanics are often not included in an integrated assessment of the multiple factors that influence osteoporotic fracture risk.

What this study adds

The Safe Functional Motion test (SFM) extends currently available performance-based clinical measures for assessing osteoporotic fracture risk by integrating assessment of spine mechanics and the vestibular system's contribution to balance during performance of habitual daily activities. This study provides the first evidence of the association between SFM scores and osteoporotic fractures of the spine and hip and between SFM scores and injurious falls.

Appendix 1. Example of Safe Functional Motion test procedures that the tester learns in the process of training and credentialing

Physiotherapy Canada 2013; 65(1);75–83; doi:10.3138/ptc.2011-25BH

References

- 1.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71(3):392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.061. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.061. Medline:19716672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black DM, Steinbuch M, Palermo L, et al. An assessment tool for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(7):519–28. doi: 10.1007/s001980170072. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001980170072. Medline:11527048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H, et al. Canadian Association of Radiologists. Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2005;56(3):178–88. Medline:16144280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs AM, Greig AM, Wark JD, et al. A review of anatomical and mechanical factors affecting vertebral body integrity. Int J Med Sci. 2004;1(3):170–80. doi: 10.7150/ijms.1.170. http://dx.doi.org/10.7150/ijms.1.170. Medline:15912196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briggs AM, Greig AM, Wark JD. The vertebral fracture cascade in osteoporosis: a review of aetiopathogenesis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(5):575–84. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0304-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0304-x. Medline:17206492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonner FJ, Jr, Sinaki M, Grabois M, et al. Health professional's guide to rehabilitation of the patient with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(Suppl 2):S1–22. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1308-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-002-1308-9. Medline:12759719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs AM, Greig AM, Bennell KL, et al. Paraspinal muscle control in people with osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(8):1137–44. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0276-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0276-8. Medline:17203276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stel VS, Pluijm SMF, Deeg DJH, et al. Functional limitations and poor physical performance as independent risk factors for self-reported fractures in older persons. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(9):742–50. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1604-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-004-1604-7. Medline:15014931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khazzani H, Allali F, Bennani L, et al. The relationship between physical performance measures, bone mineral density, falls, and the risk of peripheral fracture: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):297. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-297. Medline:19689795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards BJ, Langman CB, Martinez K, et al. Women with wrist fractures are at increased risk for future fractures because of both skeletal and non-skeletal risk factors. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):438–41. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl018. Medline:16690638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greendale GA, DeAmicis TA, Bucur A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fracture on measured physical performance: results from the MacArthur Study—MAC. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5):546–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb05001.x. Medline:10811548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerdhem P, Ringsberg KA, Akesson K. The relation between previous fractures and physical performance in elderly women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(7):914–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.03.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.03.019. Medline:16813777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greig AM, Bennell KL, Briggs AM, et al. Balance impairment is related to vertebral fracture rather than thoracic kyphosis in individuals with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(4):543–51. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0277-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0277-9. Medline:17106784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IONmed Systems. Product overview: bone safety evaluation. Gainesville (GA): IONmed Systems; 2012. [cited 2012 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.ionmed.us/bse. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cress ME, Buchner DM, Questad KA, et al. Continuous-scale physical functional performance in healthy older adults: a validation study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(12):1243–50. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90187-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90187-2. Medline:8976306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delbaere K, Van den Noortgate N, Bourgois J, et al. The Physical Performance Test as a predictor of frequent fallers: a prospective community-based cohort study. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(1):83–90. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr885oa. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269215506cr885oa. Medline:16502754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Recknor C, Grant S, MacIntyre NJ. A novel performance-based measure of functional risk for osteoporotic fracture has excellent reliability and good convergent construct validity. [Abstract] Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(Suppl 2):S226–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0842-0. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant S, Recknor C, MacIntyre NJ. Validity of the strength and flexibility domains comprising a novel performance-based measures of functional risk for osteoporotic fracture [Abstract] Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(Suppl 2):S226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0842-0. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recknor C, Grant S, Empert J, et al. Bone safety evaluation: balance domain validation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(Suppl 1):S292. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Recknor C, Grant S. Balance dysfunction and osteoporosis: a prevalence study of balance dysfunction causes [Abstract] Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(Suppl 2):S202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0358-4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacIntyre NJ, Stavness CL, Adachi JD. The Safe Functional Motion test is reliable for assessment of functional movements in individuals at risk for osteoporotic fracture. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(2):143–50. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1297-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10067-009-1297-6. Medline:19876685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lach HW, Reed AT, Arfken CL, et al. Falls in the elderly: reliability of a classification system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01626.x. Medline:1991951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindsey C, Brownbill RA, Bohannon RA, et al. Association of physical performance measures with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.028. Medline:15954047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dargent-Molina P, Schott AM, Hans D, et al. Separate and combined value of bone mass and gait speed measurements in screening for hip fracture risk: results from the EPIDOS study. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(2):188–92. doi: 10.1007/s001980050134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001980050134. Medline:10367048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taaffe DR, Simonsick EM, Visser M, et al. Health ABC Study. Lower extremity physical performance and hip bone mineral density in elderly black and white men and women: cross-sectional associations in the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(10):M934–42. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.10.m934. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.10.M934. Medline:14570862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu K, Devine A, Lewis JR, et al. “Timed up and go” test and bone mineral density measurement for fracture prediction. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(18):1655–61. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.434. Medline:21987195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]