Abstract

Background

Self-monitoring for weight loss has traditionally been performed with paper diaries. Technologic advances could reduce the burden of self-monitoring and provide feedback to enhance adherence.

Purpose

To determine if self-monitoring diet using a PDA only or the PDA with daily tailored feedback (PDA+FB), was superior to using a paper diary on weight loss and maintenance.

Design

The Self-Monitoring and Recording Using Technology (SMART) Trial was a 24-month RCCT; participants were randomly assigned to one of three self-monitoring groups.

Setting/participants

From 2006 to 2008, 210 overweight/obese adults (84.8% female, 78.1% white) were recruited from the community. Data were analyzed in 2011.

Intervention

Participants received standard behavioral treatment for weight loss which included dietary and physical activity goals, encouraged the use of self-monitoring, and was delivered in group sessions.

Main outcome measures

Percentage weight change at 24 months, adherence to self-monitoring over time.

Results

Study retention was 85.6%. The mean percentage weight loss at 24 months was not different among groups (paper diary: −1.94% [95% CI= −3.88, 0.01], PDA: −1.38% [95% CI= – 3.38, 0.62], PDA+FB: –2.32% [95% CI= –4.29, −0.35]); only the PDA+FB group (p=0.02) demonstrated a significant loss. For adherence to self-monitoring, there was a time-by-treatment group interaction between the combined PDA groups and the paper diary group (p=0.03) but no difference between PDA and PDA+FB groups (p=0.49). Across all groups, weight loss was greater for those who were adherent ≥60% versus <30% of the time, p<0.001.

Conclusions

PDA+FB use resulted in a small weight loss at 24 months; PDA use resulted in greater adherence to dietary self-monitoring over time. However, for sustained weight loss, adherence to self-monitoring is more important than the method used to self-monitor. A daily feedback message delivered remotely enhanced adherence and improved weight loss, which suggests that technology can play a role in improving weight loss.

Background

The cornerstone of weight management is lifestyle modification, including reduced energy intake, increased energy expenditure, and behavioral treatment.1 The structured group behavioral weight loss program, which incorporates these three components, is the most efficacious nonmedical treatment for moderate obesity2 and, more recently, for the treatment of severe obesity.3,4 The core behavioral change strategies, based on social cognitive theory, include multiple components. Most salient are goal-setting, self-monitoring, and feedback provided by behavioral counselors to assist with development of problem-solving skills.5

More than 2 decades ago, dietary self-monitoring was reported to be the centerpiece of behavioral weight loss treatment.6 Since then, the evidence has continued to build, demonstrating a consistent relationship between self-monitoring and weight loss7 and weight loss maintenance.8 Few studies have tested strategies for long-term maintenance of weight loss9–11; however, research provides evidence that ongoing contact is a strategy that enhances long-term adherence.12 The use of an electronic diary with automatic feedback could potentially serve as a form of contact.

The most frequently used method to self-monitor diet is the paper diary, which can be timeconsuming and tedious to complete. Paper diaries also limit the timeliness of supportive and motivational feedback delivered by the interventionist due to the lag time between receipt of the paper diary and delivery of feedback to the participant. Because of the importance of self-monitoring in weight loss, new technologies are being developed that can reduce the burden while providing immediate, tailored feedback and motivation enhancement to the participant and also increase adherence to this important behavior change strategy.

A wealth of empirical evidence demonstrates that immediate positive reinforcement for a desired behavior leads to increases in the behavior; the more proximal the reinforcer to the desired behavior, the more likely it will be to increase the desired behavior.13 Applied to the important behavior of self-monitoring, informational and reinforcing feedback has the potential to increase self-monitoring and thus enhance goal attainment. The rapid advancement and adoption of wireless devices provide numerous opportunities for the incorporation of mHealth interventions for the delivery of feedback to individuals engaged in weight loss treatment.14, 15

Objective

This randomized, three-group behavioral clinical trial drawing on Kanfer’s self-regulation model,16 sought to determine if self-monitoring diet using a PDA alone (PDA) or with daily tailored feedback (PDA+FB) was superior to using a conventional paper diary on weight loss and weight loss maintenance in a 24-month study. Additionally, it compared the effect of treatment group assignment (paper diary vs PDA, PDA+FB and PDA vs PDA+FB) on adherence to self-monitoring. Lastly, it examined whether weight loss would be greatest for those who were adherent to self-monitoring.

Methods

Design Overview

The study design and methods for this 24-month RCT have been detailed elsewhere17, 18and thus are briefly reviewed here. For each cohort, participants were randomly assigned, with equal allocation via a computer-implemented minimization algorithm that stratified on gender and race, to either the Paper Diary, PDA, or PDA+FB group. Participants were provided with a standard behavioral weight loss intervention and were assessed semi-annually. They were compensated $50 per assessment excluding baseline. Paper diary group participants who completed the 24-month assessment were given a new PDA and an instruction session on the self-monitoring software. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants; the study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB.

Setting and Participants

The SMART Trial included 210 participants recruited from the community in three cohorts between 2006 and 2008. The intervention took place at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, and the assessments were completed in the University of Pittsburgh Clinical Translational Research Center at Montefiore Hospital, adjacent to the School of Nursing. Individuals were eligible if they were aged ≤59 years with a BMI between 27 and 43. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, conditions requiring medical supervision of diet or exercise, physical limitations precluding ability to walk, an eating disorder, and participation in a weight loss program or change in medications for a psychological disorder in the preceding 6 months.

Intervention

The standard behavioral intervention, a slightly modified version of the Paving the Road to Everlasting Food and Exercise Routines (PREFER) Trial intervention,19 was based on social cognitive theory and comprised four main components: (1) group sessions; (2) goal-setting and self-monitoring; (3) daily dietary (energy and fat intake) goals; and (4) weekly exercise goals.

Group sessions

Separate evening intervention sessions were held for each treatment group. Meetings were held weekly for Months 1–4, biweekly for Months 5–12, and monthly for Months 13–18. Only one session was held during the final 6 months; this focused on weight loss maintenance. After participants were trained in their assigned self-monitoring method, session materials were identical for the groups.

Self-Monitoring

The sole difference among the groups was the mode of self-monitoring that they were asked to use. Paper diary group participants were provided with standard paper diaries and a nutritional reference book; they were encouraged to calculate subtotals after each entry. PDA group participants were given a PDA with Dietmate Pro© software for self-monitoring diet, which tallied consumed calories and fat grams and compared intake to goals. The PDA+FB group had feedback software that interacted with the self-monitoring software via a custom algorithm to provide a daily message regarding intake. If a participant exceeded their fat gram goal, they might have received a message at the end of the day stating, “Be aware of high fat snacks tonight.” If a participant had not self-monitored, the message would be a reminder such as, “Taking a few minutes now to record will help you meet your goals.” Additional details of the timing and content of the messages have been published.20

At each session, participants turned in their diaries. If they were unable to attend the session, participants in the paper diary group could mail in the diaries; for those in the PDA groups, the previous diaries were stored in the PDA and were available the next time the participant came into the center. The interventionists reviewed and provided handwritten feedback on the diaries (paper diaries or print-outs of the PDA data) and returned them at the next session.

Dietary and exercise goals

Participants’ daily energy consumption goals were 1200 to 1800 calories, based on weight and gender; ≤25% of total calories could be from fat. The weekly physical activity goal was 180 minutes by 6 months and increased by 30 minutes semi-annually.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was percentage weight change from baseline to 24-months, which is used by many weight loss studies because it controls for baseline weight. Because there was only one contact in the final 6 months, adherence to self-monitoring was limited to 18 months. At each assessment, the participants’ weight was measured on a digital scale by study staff. The secondary endpoint was adherence to self-monitoring of diet. Adherence was defined as the percentage of days that participants recorded an adequate number of calories (i.e., 50% of their daily goal) in their diaries. If a diary was not submitted, nonadherence was assumed.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size of 210 was chosen to have at least 0.80 power for two-sided hypothesis testing via linear contrasts from a linear mixed model at a significance level of 0.05 when comparing changes in weight at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months relative to baseline between (1) the combined PDA groups (PDA, PDA+FB) and the paper diary group at a standardized mean difference (d) of 0.48 and (2) the PDA group and the PDA+FB group at d=0.56. To adjust21 for anticipated attrition of at most 25.7% over 24 months,22 210 subjects were enrolled to retain at least 156 subjects.

Data were analyzed in 2011 with SAS 9.1. Significance was set at 0.05 for two-sided hypothesis testing and 95% CIs were used. Intent-to-treat principle was used, where subjects were analyzed as randomized. Summary statistics were reported as frequency count (%) and mean ((SD) or ±SE). Baseline characteristics were compared among treatment groups using ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis for continuous variables and chi-square test of independence or Fisher’s exact test for categoric variables.

Linear mixed modeling with linear contrasts was applied to assess treatment group, time, and interaction effects on percentage weight change from baseline to 24 months for paper diary versus PDA, PDA+FB and for PDA versus PDA+FB. ANOVA was used to examine the treatment group effect on percentage weight change at 24 months. Linear mixed modeling was employed to examine treatment group, time and interaction effects on dietary self-monitoring adherence for the first 18 months as well as treatment group, time, dietary self-monitoring adherence (<30%, 30%–59%, ≥60%) and interaction effects on percentage weight change. Marginal modeling via generalized estimating equations was utilized to examine treatment group, time and interaction effects on dietary self-monitoring adherence (<60%, ≥60%) during the first 18 months.

Various strategies were considered to handle missing weight assessments (e.g., linear mixed modeling assuming ignorable missingness; last-observation-carried-forward; assuming a 0.3 kg/month23 increase for subjects leaving the study, with linear mixed modeling handling intermittent missingness); however, the same conclusions were drawn regardless of the missing data approach used. Hence, the results are based on assuming an increase of 0.3 kg/month for all missing observations. Additionally, sensitivity analyses for suspected influential cases supported the robustness of the findings as conclusions were maintained following case omission.

Results

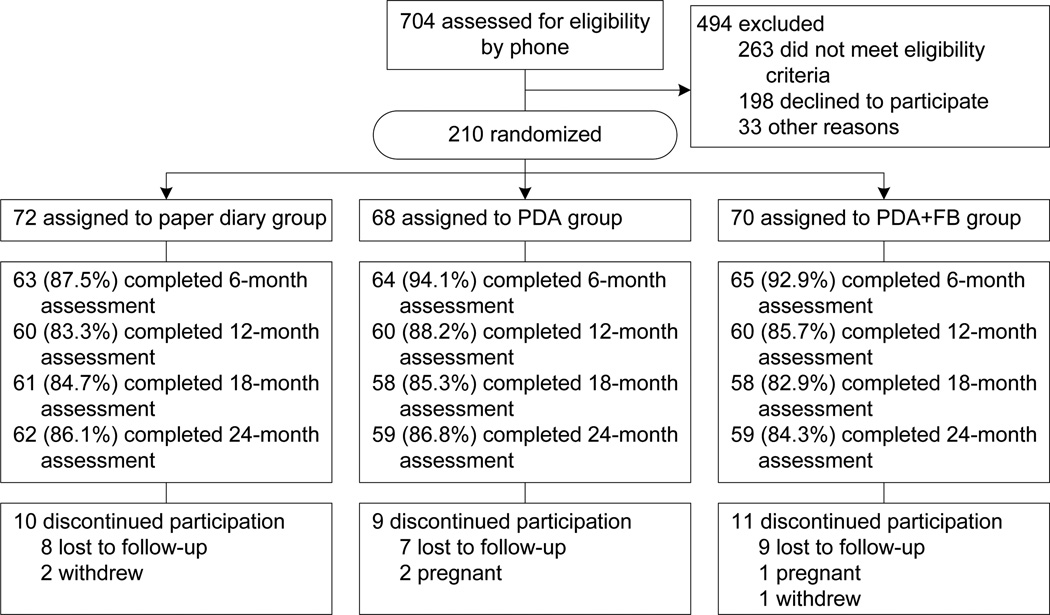

Detailed baseline characteristics have been published18 as have the short-term results.24 To summarize, a majority of participants were white (78.1%) women (84.8%) with an average age of 46.8 years and education of 15.7 years. The treatment groups did not differ by sociodemographic or baseline anthropometric measures. Retention at 24 months was 85.7% with no differential attrition (see Figure 1). Completers were older than noncompleters (47.66 (8.38) years vs 41.77(10.95) years, p<0.001), which may have been influenced by three pregnancy-related withdrawals. Completers also had a lower baseline BMI (33.74 (4.44) vs 35.62 (4.47), p=0.04).

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram.

PR, PDA+FB, PDA with feedback

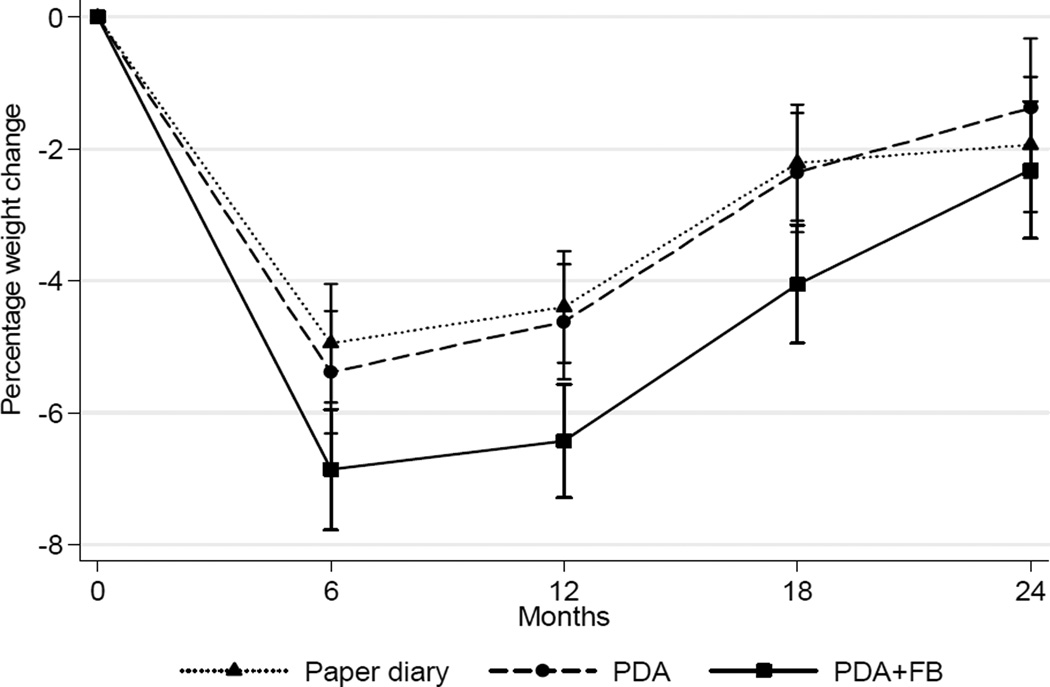

Percentage Weight Change

A significant within-group difference in weight over time was found for the PDA+FB group (p=0.02) with an average 2.32% weight loss but not for the other two groups (paper diary: – 1.94%, PDA: –1.38%). There was no difference among the three groups in percentage weight change over time (p=0.33). The mean (SD) absolute weight change from baseline to 24 months was: paper diary group −1.77 (7.23) kg; PDA group −1.18 (8.78) kg; and PDA+FB group −2.17 (7.04) kg. Figure 2 depicts the weight change patterns over time.

Figure 2. Percentage weight change (M±SE) at all time-points by treatment group.

Note: (A) as predicted by a linear mixed model; (B) as determined by descriptive data

PR, PDA+FB, PDA with feedback

As detailed in Table 1, average weight loss decreased at each assessment point; however, the significant within-group weight loss observed at 6 and 12 months was no longer evident after 18 months in the paper diary and PDA groups. At 6 months, a higher proportion of the PDA+FB group achieved ≥5% weight loss; however, this was not sustained at 24 months. Overall, 52% (n=110) lost ≥5% of baseline body weight at 6 months; of that group, 19% retained that weight loss at 24 months with no differences among the groups. Despite the weight regain among some participants, mean weight at 24 months was below the mean baseline weight.

Table 1.

Percentage weight change (M (SD)) by treatment group overall and by self-monitoring adherence during active treatment

| Treatment Group |

Percentage of time adherent to self-monitoring |

6 months | 12 months | 18 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper Diary (n=72) |

Overall | −4.59 (5.66) | −4.04 (6.67) | −1.99 (7.04) |

| < 30% | −0.20 (3.20); n=18 | −2.24 (6.03); n=53 | −1.77 (7.54); n=66 | |

| 30%–59% | −2.76 (4.73); n=21 | −8.64 (4.93); n=7 | −0.99 (1.11); n=2 | |

| At least 60% | −8.93 (5.63); n=33 | −11.47 (7.73); n=12 | −10.15 (8.45); n=4 | |

| PDA (n=68) |

Overall | −4.88 (6.20) | −4.04 (7.20) | −2.01 (8.09) |

| Less than 30% | −0.96 (5.67); n=6 | −1.02 (6.49); n=38 | −0.04 (7.51); n=54 | |

| 30% to 59% | −1.87 (6.77); n=14 | −6.68 (6.67); n=12 | −12.54 (9.59); n=6 | |

| At least 60% | −6.97 (6.76); n=48 | −10.86 (8.29); n=18 | −10.35 (9.42); n=8 | |

| PDA+FB (n=70) |

Overall | −6.58 (6.77) | −6.02 (7.73) | −3.81 (7.07) |

| Less than 30% | 0.04 (4.40); n=5 | −2.00 (5.06); n=32 | −2.53 (6.52); n=57 | |

| 30% to 59% | −2.22 (4.97); n=14 | −4.19 (5.82); n=12 | −11.67 (9.15); n=5 | |

| At least 60% | −8.82 (6.57); n=51 | −12.93 (8.56); n=26 | −10.15 (8.64); n=8 |

Note: 0.3 kg/month was added to previous observation for missing data. Marginal modeling with generalized estimating equations showed that the proportion of participants in the most adherent group (≥60% adherent) was higher in each of the PDA groups compared to the paper diary group (PDA vs paper diary, p=0.03; PDA+FB vs paper diary, p=0.01).

PDA+FB, PDA plus feedback

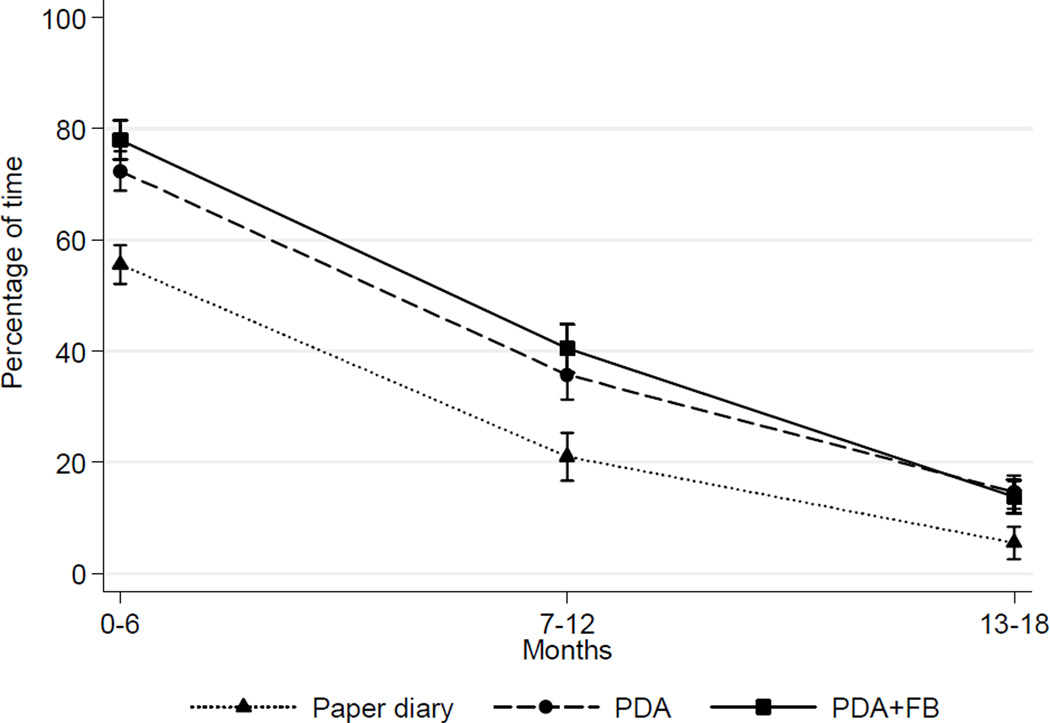

Self-Monitoring

The percentage of time that participants self-monitored is depicted in Figure 3. Adherence to dietary self-monitoring had time (and group effects (p’s<0.001). Difference in adherence over time between the combined PDA and PDA+FB group and the paper diary group was significant (p=0.03).

Figure 3. Percentage of time (M±SE) participants were adherent to self-monitoring during active treatment.

Note: As predicted by a linear mixed model

PR, PDA+FB, PDA with feedback

Adherence to dietary self-monitoring strongly predicted weight loss at all time points (Table 1; Figure 4) When self-monitoring adherence was examined by three levels (<30%, 30%–59%, ≥60%), weight loss was different (p<0.001). A greater proportion of the PDA groups, compared to paper diary group, was adherent ≥60% of the time (PDA vs paper diary, p=0.03; PDA+FB vs paper diary, p=0.01) and lost more weight than those who were <30% adherent (p<0.001). At 18 months, 19%–20% of the PDA groups remained adherent ≥30% of the time compared to 8% of the paper diary group; also, participants in the PDA and PDA+FB groups whose adherence had declined to the 30%–59% category, had weight losses similar to those who were ≥60% adherent.

Figure 4. Percentage weight change (M±SE) by percentage of time adherent to self-monitoring during active treatment.

Note: Time percentages are <30% vs 30%–59% vs ≥60%.

Discussion

Although the percentage weight change was significant only for the PDA+FB group, it was clinically similar to the weight losses of the other groups. However, there was a time-by-treatment group interaction between the combined PDA groups and the paper diary group for adherence to self-monitoring. Moreover, a difference in weight loss across three levels of self-monitoring adherence was observed.

A few explanations can be posited for the lack of weight loss at 24 months in the paper diary and PDA groups. The paper diary group used the potentially more burdensome method of self-monitoring with no automatic feedback. Although the PDA group was more adherent than the paper diary group, this difference in adherence did not lead to differences in weight loss, suggesting an influential role for daily feedback.

Two studies that focused on self-monitoring methods reported an association between self-monitoring and weight loss; however, neither reported group differences in weight loss.25, 26 Methodologic limitations in both preclude one from concluding that alternative approaches to the paper diary were superior. No other study has examined the effect mobile technology with or without feedback on weight loss and adherence to self-monitoring during a 2-year behavioral treatment study. This novel and rigorous design makes comparisons challenging. Two studies have shown enhanced adherence with PDA use; however, the observation period was limited to 1 month.27, 28

The current weight change and retention results can be compared to two other 2-year weight loss studies that used SBT but not PDAs. Sacks and colleagues compared the efficacy of four diets augmented by a group and individual sessions.29 Foster and colleagues compared a low-carbohydrate to a low-fat diet and conducted group sessions.30 Although the behavioral intervention for these studies lasted the full 2 years, the reported retention was 80% for Sacks et al. and 63% for Foster et al., compared to 85.6% in the current study where there was only one session in the last 6 months.

Analytic approaches also differed. Foster et al. used longitudinal models without fixed imputations for missing data, whereas Sacks et al. and the current study used the most conservative method,1 assuming a 0.3 kg/month increase for missing weight data. Thus, the longer intervention duration and more liberal analytic approach used by Foster et al. may have contributed to the greater weight losses (7%) reported for that study. Sacks et al. reported a 6-kg weight loss at 6 months, which represented 7% of baseline weight; however, at 24 months they observed a weight loss only slightly better than observed here, 2.9–3.6 kg. The smaller weight loss observed in the current study, which was due to weight regain in the latter months, reinforces the consistent finding that ongoing contact is needed to sustain adherence and the associated long-term weight loss.10, 11

Although improved self-monitoring adherence did not result in better weight loss maintenance, when subgroups by level of adherence were examined, method of self-monitoring was notably related to self-monitoring adherence, and that, in turn, was related to weight loss maintenance (Table 1). Throughout the study, a higher proportion of the PDA groups were more adherent to self-monitoring. Weight loss among those who were ≥60% adherent was greater than that among those who were <30% adherent.

Also, at 18 months, the weight losses in the PDA groups were similar between those who were in the upper two categories of adherence (>60% and 30%–59%), suggesting that those who were using a PDA were able to maintain the weight loss at a lower level of self-monitoring adherence after engaging in this behavior for several months. These findings have implications for maintenance and the use of mobile technology for dietary self-monitoring and use of feedback in weight loss treatment. Indeed, preliminary studies conducted by Patrick et al. and Gerber et al. demonstrated the benefits of using cellular phone technology in weight loss and maintenance intervention delivery.31, 32

The greater weight loss among those who were adherent ≥60% of the time in all groups suggests that self-monitoring adherence is more important than self-monitoring method. Wadden reported that participants who were in the upper third of adherence lost more weight than those who were in the lower third of adherence.23 Adherence in the first 6 months of the POUNDS LOST trial predicted weight reduction throughout the trial.33 Collectively, these studies add to the evidence of the importance of self-monitoring.

The PDA+FB group’s achievement of a small weight loss in the absence of ongoing contact indicates that the use of an electronic diary plus feedback could increase adherence to a point that will enhance weight loss maintenance. Moreover, more participants in the PDA groups achieved ≥60% adherence; those individuals lost more weight and maintained most of it. The use of mobile technology shows great promise for reducing the burden of self-monitoring. An added benefit is the potential for individuals to receive more proximal feedback and to track progress to their goals. The impact of more-proximal feedback on self-monitoring and weight loss needs further investigation; the means to provide this is linked to new and emerging technologies such as smartphones.

This study was the first large trial to compare the efficacy of using mobile technology versus a traditional paper diary in improving self-monitoring adherence and weight loss. Additional strengths included the randomized trial design with objective anthropometric measures and an innovative approach to examining the use of mobile technology. Moreover, this study achieved 86% retention at 2 years and a 21% minority representation. The male representation was disappointing but not atypical of weight loss studies. As previously reported, recruitment strategies targeting men were implemented; many of the men who were initially eligible via the telephone screening did not complete the screening process.20

Conclusion

The current findings strongly suggest that adherence to self-monitoring is associated with successful short- and long-term weight loss. Findings from another long-term trial, the Women’s Health Initiative, 34 suggested that improved tools for self-monitoring are needed to enhance adherence in long-term clinical trials. The results of this 2-year trial underscore the fact that adherence to self-monitoring is more important than the method chosen to self-monitor; however, the use of technology-based tools markedly improved self-monitoring adherence in a larger number and those participants lost more weight and also sustained the loss. In addition, the current results demonstrate that a daily feedback message delivered remotely enhanced adherence and improved weight loss, which has major implications for the potential use of technology such as smartphones in improving weight loss treatment. This study represents an early step in the use of mobile technology in weight loss and weight maintenance efforts.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants NIH/NIDDK R01-DK071817, R01-DK071817-04S1, R01-DK071817-05S1, and NIH/NINR K24-NR010742. The conduct of the study was also supported by the Data Management Core of the Center for Research in Chronic Disorders at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing (NIH-NINR P30-NR03924), the General Clinical Research Center (NIH-NCRR-GCRC 5M01-RR000056) and the Clinical Translational Research Center (NIH/NCRR/CTSA Grant UL1 RR024153) at the University of Pittsburgh.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

We are deeply indebted to Alison Keating and Sushama Acharya for delivering the intervention, to Edvin Music for data management and technology support, to India Loar for study coordination, and to Megan Barna, Britney Beatrice, and Leah McGhee for their role in data collection; and to all the SMART trial participants.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:226–2238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004;12(suppl):S151–S162. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodpaster BH, DeLany JP, Otto AD, et al. Effects of Diet and Physical Activity Interventions on Weight Loss and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Severely Obese Adults: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1795–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan DH, Kushner R. The State of Obesity and Obesity Research. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1835–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Bray GA, Bourchard C, James WPT, editors. Handbook of obesity: Clinical applications. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperduto WA, Thompson HS, O'Brien RM. The effect of target behavior monitoring on weight loss and completion rate in a behavior modification program for weight reduction. Addict Behav. 1986;11:337–340. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(1):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1 Suppl):222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Lutes LD, Bobroff LB, et al. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in underserved rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(21):2347–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, Kris-Etherton P, Van Horn L, Lichtenstein AH, et al. Interventions to Promote Physical Activity and Dietary Lifestyle Changes for Cardiovascular Risk Factor Reduction in Adults. A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:406–441. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers RG, Osborn JG. Fundamentals of Behavior. New York: West Publishing Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick K, Griswold WG, Raab F, Intille SS. Health and the mobile phone. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tufano JT, Karras BT. Mobile eHealth interventions for obesity: a timely opportunity to leverage convergence trends. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(5):e58. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.5.e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanfer FH. The maintenance of behavior by self-generated stimuli and reinforcement. In: Jacobs A, Sachs LB, editors. The psychology of private events. New York: Academic Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke LE, Conroy MB, Sereika SM, Elci OU, Styn MA, Acharya SD, et al. The effect of electronic self-monitoring on weight loss and dietary intake: a randomized behavioral weight loss trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(2):338–344. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke LE, Styn MA, Glanz K, et al. SMART trial: A randomized clinical trial of selfmonitoring in behavioral weight management -design and baseline findings. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke LE, Choo J, Music E, et al. PREFER study: A randomized clinical trial testing treatment preference and two dietary options in behavioral weight management -- rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27(1):34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke LE, Styn MA, Glanz K, et al. SMART trial: A randomized clinical trial of selfmonitoring in behavioral weight management-design and baseline findings. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(6):540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachin J. Introduction to sample size determination and power analysis for clincial trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1981;2:93–113. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke LE, Hudson AG, Warziski MT, et al. Effects of a vegetarian diet and treatment preference on biochemical and dietary variables in overweight and obese adults: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):588–596. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2111–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke L, Conroy M, Sereika S, et al. The effect of electronic self-monitoring on weight loss and dietary intake: a randomized behavioral weight loss trial. Obesity. 2011;19:338–344. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helsel DL, Jakicic JM, Otto AD. Comparison of techniques for self-monitoring eating and exercise behaviors on weight loss in a correspondence-based intervention. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1807–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yon BA, Johnson RK, Harvey-Berino J, Gold BC, Howard AB. Personal digital assistants are comparable to traditional diaries for dietary self-monitoring during a weight loss program. J Behav Med. 2007;30(2):165–175. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beasley JM, Riley WT, Davis A, Singh J. Evaluation of a PDA-based dietary assessment and intervention program: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(2):280–286. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glanz K, Murphy S, Moylan J, Evensen D, Curb JD. Improving dietary self-monitoring and adherence with hand-held computers: a pilot study. Am J Health Promot. 2006;20(3):165–170. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(9):859–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, et al. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(3):147–157. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerber BS, Stolley MR, Thompson AL, Sharp LK, Fitzgibbon ML. Mobile phone text messaging to promote healthy behaviors and weight loss maintenance: a feasibility study. Health Informatics J. 2009;15(1):17–25. doi: 10.1177/1460458208099865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, et al. A text message-based intervention for weight loss: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williamson DA, Anton SD, Han H, et al. Adherence is a multi-dimensional construct in the POUNDS LOST trial. J Behav Med. 2010;33:35–46. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9230-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Henry H, Rodabough R, et al. Additional self-monitoring tools in the dietary modification component of The Women's Health Initiative. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(1):76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]