Abstract

We investigated the occurrence and genetic diversity of Trichoderma and Hypocrea in Manipur which lies in the Indo-Burma biodiversity hot spot region. 65 Trichoderma isolates were identified at species level by morphological as well as sequence based analysis of the internal transcribed spacer region 1 and 4. Altogether 22 different species of Trichoderma and Hypocrea were found, of which Trichoderma harzianum represent the dominant species. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a clear cut distinction of strains isolated from various collection sites which further hints the need for detail study of Trichoderma on molecular level.

Background

The hypocreomycetidae genus Trichoderma was known for their rapid growth, capability of utilizing diverse substrates and resistance to noxious chemicals [1]. They are often the predominant components of the mycoflora in soils of various ecosystems, such as agricultural fields, prairie, forest, salt marshes and deserts, in all climatic zones [2]. Several Trichoderma species are significant biocontrol agents against fungal plant pathogens for nutrients, stimulators of plant health, or inducers of plant systemic resistance to pathogens [3]. Trichoderma species produce a wide diversity of metabolites as well as the toxins and trichothecenes that display in vitro cytotoxicity [4].

Due to the ecological importance of Trichoderma and its application as a biocontrol agent in the field, it is important to understand its biodiversity and biogeography. However, accurate species identification based on morphology is difficult at best because of the paucity and similarity of useful morphological characters [5, 6] and increasing numbers of morphologically cryptic species that can be distinguish only through their DNA characters are being described [7]. With the advent of molecular methods and identification tools, which are based on sequence analysis of multiple genes, it is now possible to identify every Trichoderma isolate and /or recognize it as a putative new species [8]. Considering the environmental conditions as one of the important factors, the right selection of BCAs, which begins with a safe characterization of biocontrol strains in the new taxonomic schemes of Trichoderma, is equally important since the exact identification of strains to the species level is the first step in utilizing the full potential of fungi in specific applications [9]. The current diversity of the holomorphic genus Hypocrea/Trichoderma is reflected in approximately 160 species, the majority of which have been recognized on the basis of DNA sequence analysis and molecular phylogeny of pure cultures and/or herbaria specimens [8]. Manipur belongs to the rich Indo-Burma mega biodiversity hotspot region of the world which lies between 23°47'- 25°45' North latitude and 96°61'- 94°48' East longitude. This region is representing an active center of gene pool and having a diverse range of Trichoderma spp. with potential biocontrol activity.

Methodology

Geography of sample sites:

Sampling was done from nine different districts of Manipur comprising of four different agro-climatic zones viz. i. Subtropical plain zone, ii. Sub-tropical hill zone, iii. Temperate sub-Alpine zone and iv. Mid tropical hill zone, which differ in their geographic location, altitude and climate.

Isolation of pure cultures:

Trichoderma selective medium [10] was used as a selective medium for Trichoderma, using the soil dilution plating method. Putative Trichoderma colonies were purified by two rounds of subculturing on potato-dextrose agar (PDA).

Morphological analysis:

For morphological analysis, strains were grown on PDA at 25ºC - 30°C. Microscopic observations, measurements were made from slide preparation by using trinocular microscope. Conidiophore structure and morphology were examined on macronematous conidiogenous pustules or from fascicles when conidia were maturing. Conidial morphology and sizes were recorded after 6-7 days of incubation.

DNA isolation:

The genomic DNA of Trichoderma isolates were extracted from the pure culture of young and actively growing hyphae using NBAIM method. Mycelia were obtained by inoculating potato dextrose broth (PDB;Difco) with aerial mycelium from PDA plates, and after incubation at 24ºC for 48h on an orbital shaker (120 rpm). Mycelia were collected on filter paper in a Buchner funnel, washed with sterile water and grinded in a sterile motar and pastle [11] with minor modifications as described by [12].

DNA amplification:

Trichoderma nuclear small-subunit rDNA sequence containing the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) 1 and 4 regions and the 5.8S rRNA gene were amplified by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in an automated thermocycler using a combination of two specific primers ITS1 (TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG) and ITS 4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) [13].

Sequence assembly and alignment:

Amplification products obtained from PCR reactions with unlabeled ITS primers (ITS1 & ITS4) were sended to B'Genei for sequencing. DNA sequences obtained for each strain from each forward (ITS) and reverse (ITS4) primer were inspected individually for quality. Both strands of the DNA were then assembled to produce a consensus sequence for each strain using Gene Runner software and submitted to NCBI blast. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW tool with default parameter in MEGA 5.05.

Phylogenetic Analysis:

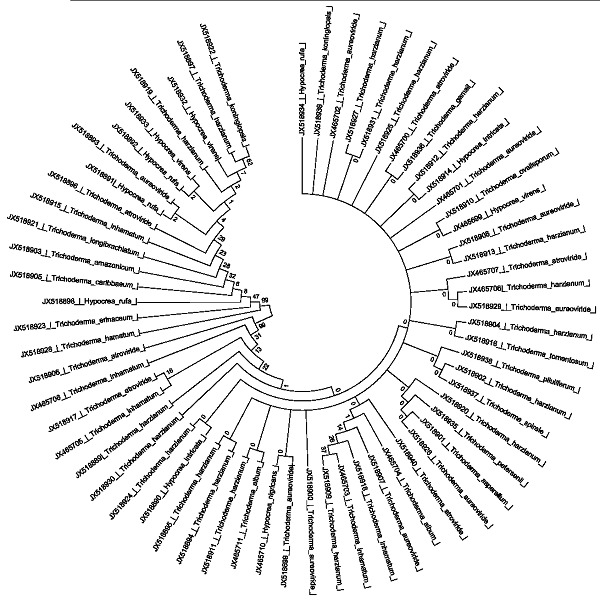

The phylogenetic analyses of the aligned sequence were performed using MEGA 5.05 [14] with 1000 number of bootstrap replicates and Neighbor-Joining method of statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 193 isolates were obtained from the nine geographically diverse areas of Manipur. Out of the total isolates, 65 representative isolates were preliminarily identified at the species level by morphological characteristics. Later, 22 different Trichoderma spp. among the total 65 strains were identified by the analysis of their ITS1 and ITS4 sequences (amplicon sizes ranging from 560-600bp). T. harzianum was the most dominant species among the 22 Trichoderma spp. Sequence strains of the nearest accession numbers obtained from the Gene Bank along with the strain identity percentage and the result of the blast searches are listed in Table 1 (see supplementary material). Phylogenetic studies revealed considerable variations among the isolates collected from different districts of Manipur.

Discussion

We have carried out a survey of the occurrence of Trichoderma and Hypocrea in Manipur which aimed to obtain a more complete picture of the biodiversity of these genuses in Manipur. A collection of 65 isolates obtained from 9 different districts of Manipur were identified by morphological observations and by analysis of the ITS sequence analysis. A wide diversity of Trichoderma isolates were found (22 species were identified among 65 isolates) in comparison with the studies on the biodiversity of Trichoderma in South-East Asia [15], Austria [16], South America [5], China [17], Sardinia [18] and in Poland [19].

We found that the amplification products for the ITS region of 65 species of Trichoderma collected from nine different districts of Manipur ranges from 560-600bp. These results were in accordance with [20] and other several workers also observed the amplified rDNA fragment of approximately 500 to 600 bp by ITS-PCR in Trichoderma [21]. T. harzianum, which was the most dominant species in this study, was reproducibly associated with all the types of soils of nine different districts [22]. In previous studies that used cultivation-dependent methods to quantify Hypocrea/Trichoderma in various habitats, T. harzianum sensu lato represented the most dominant species [18, 23, 6]. Among the total 675 strains belonging to Trichoderma and Hypocrea strains available in the International Subcommision on Trichoderma and Hypocrea, 6 strains from the present study namely H. intricata, T. amazonicum, T. album, H. rufa, T. gamsii and H. nigricans have not been reported in ISTH. The results from this study stress the importance of the use of molecular identification tools to describe the biodiversity of Trichoderma in a natural habitat. This further corroborate from phylogenetic tree (Figure 1). The high number of species of Trichoderma and Hypocrea found in the nine different districts of Manipur confirms that this is one of india's biologically most diverse regions with a large portion of endemic species.

Figure 1.

phylogenetic analysis of Trichoderma strains using MEGA 5.05 with 1000 number of replications and Neighbour-joining statistical method.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

Authors like to thanks to Department of Biotechnology, Government of India to provide financial support during this study.

Footnotes

Citation:Kamala et al, Bioinformation 9(2): 106-111 (2013)

References

- 1.Oda T, et al. Mycol Res. 2004;108:885. doi: 10.1017/s0953756204000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith WH. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1995;32:179. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1995.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey BA, et al. Planta. 2006;224:1449. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degenkolb T, et al. Mycol Prog. 2008;7:177. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druzhinina IS, et al. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:813. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Respinis S, et al. Mycol Prog. 2010;9:79. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atanasova L, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:7259. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01184-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubicek CP, et al. J Zhejiang Univ Sci. 2008;9:753. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0860015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieckfeldt E, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2418. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2418-2428.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JP. Soil Sci. 1950;69:215. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raeder U, Broda P. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1985;1:17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermosa MR, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1890. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.1890-1898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White TJ, et al. PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications. 1990;315:322. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura K, et al. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubicek CP, et al. Fungal Genet Biol. 2003;38:310. doi: 10.1016/s1087-1845(02)00583-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wuezhowski M, et al. Microbiol Res. 2003;158:125. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang CL, et al. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;25:251. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migheli Q, et al. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:35. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blaszezyk L, et al. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:233. doi: 10.1007/s13353-011-0039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee PK, et al. Science Correspondence. 2002;83:373. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venkateswarlu R, et al. Plant Pathol. 2008;38:569. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Druzhinina IS, et al. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachow C, et al. ISME J. 2009;3:79. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.