Abstract

Background

Considerable evidence suggests that sensitivity to the stimulant effects of alcohol and other drugs is a risk marker for heavy or problematic use of those substances. A separate body of research implicates negative emotionality. The goal of the present study was to evaluate the independent and interactive effects of the stimulant response, assessed with an amphetamine challenge, and negative emotionality on alcohol and drug use.

Methods

Healthy young women and men completed the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) and an inventory assessing alcohol and other drug use. Subsequently, the effects of 10 mg d-amphetamine were determined in the laboratory using the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Hierarchical regression analyses evaluated the effects of amphetamine response and the MPQ factor Negative Emotionality on measures of substance use.

Results

The amphetamine response moderated relationships between negative emotionality and alcohol use: In combination with a robust amphetamine response (i.e., enhanced stimulant effects as compared to baseline), negative emotionality predicted greater alcohol consumption, more episodes of binge drinking, and more frequent intoxication in regression models. A strong stimulant response independently predicted having used an illicit drug, and there was a trend for it to predict having used alcohol. Negative emotionality alone was not associated with any measure of alcohol or drug use.

Conclusions

Consistent with the idea that emotion-based behavioral dysregulation promotes reward-seeking, a high level of negative emotionality was associated with maladaptive alcohol use when it co-occurred with sensitivity to drug-based reward. The findings contribute to our understanding of how differences in personality may interact with those in drug response to affect alcohol use.

Keywords: Stimulant response, d-amphetamine, negative emotionality, substance use, endophenotype

INTRODUCTION

Sensitivity to the stimulant effects of alcohol is a candidate marker of vulnerability for alcohol use disorders (for reviews, see Morean and Corbin, 2010; Newlin and Renton, 2010; Newlin and Thomson, 1990; Quinn and Fromme, 2011; Ray et al., 2010). The subjective response to amphetamine, a prototypic stimulant drug, has also been associated with risk for alcoholism, measured in relation to family history (Gabbay, 2005), genetic polymorphisms (Dlugos et al., 2011), personality (Hutchison et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2006; 2009; Stoops et al., 2007; White et al., 2006), and consumption (Stanley et al., 2011; Stoops et al., 2003). The association between an enhanced stimulant response and risk is often interpreted in terms of reinforcement: Individuals who experience positive, mood-enhancing effects of a drug are more likely to use that drug—and potentially others with similar effects—than those who do not experience such effects (de Wit, 1998; Haertzen et al., 1983).

There is also substantial evidence that a high level of negative emotionality is associated with risk for alcohol and drug use disorders (Chassin et al., 2004; Elkins et al., 2006; Hicks et al., 2012; Krueger, 1999; Loukas et al., 2000; Sher et al., 2005). For individuals who experience frequent and intense negative emotions, substance use may be an attempt to regulate, escape, or avoid these undesirable affective states (Carmody, 1992; Gonzalez et al., 2011; Greeley and Oei, 1999; Sher et al., 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2007). Whereas this negative reinforcement path to substance use has been well studied, a smaller body of work addresses a positive reinforcement path through which negative emotionality may impact substance use. This work suggests that negative emotions promote impulsive action, disrupting control and biasing behavioral decisions in favor of those that lead to immediate reward (Baumeister and Scher, 1988; Cyders and Smith, 2008; Gipson et al., 2012; Gonzalez et al., 2011). In individuals vulnerable to the stimulant effects of alcohol or drugs, this dysregulation by negative affect may lead to reward-seeking through substance use.

The Stimulant Response

Evidence suggests an association between the stimulant response to alcohol (measured in the rising blood alcohol curve) and risk for heavy or problematic alcohol use. Individuals who prefer alcohol over placebo in the laboratory report a marked stimulant response to that drug (Chutuape and de Wit, 1994), and an enhanced subjective stimulant response to alcohol has also been associated with greater consumption after a priming dose in an anticipatory stress paradigm (Corbin et al., 2008). Heavy drinkers report greater stimulant effects to a single dose of alcohol as compared with light drinkers (Holdstock et al., 2000; King et al., 2002; 2011), and an enhanced stimulant response predicts future binge drinking in this group (King et al., 2011). It has also been reported that individuals with a family history of alcoholism, a well-established risk factor (Bierut et al., 1998; Merikangas et al., 1998), exhibit a more pronounced physiological (Conrod et al., 1997; Peterson et al., 1996) and subjective (Erblich et al., 2003; Morzorati et al., 2002) response to the stimulant effects of alcohol as compared to individuals without such a family history. Animal models are consistent with these findings: Selectively bred alcohol-preferring rats are more sensitive to alcohol-induced locomotor activation than non-preferring rats (Agabio et al., 2001; Murphy et al., 2002).

Although fewer studies have evaluated the stimulant response to amphetamine in relation to measures of risk, the findings are similar to those that have been reported for alcohol. Individuals who prefer amphetamine over placebo in a behavioral drug preference procedure, considered a measure of risk for abuse, exhibit an enhanced stimulant response to amphetamine (de Wit et al., 1986; Gabbay, 2003). Similarly, in mice, there is a relationship between sensitivity to the stimulant effects of amphetamine and susceptibility to amphetamine-induced conditioned place preference, a common metric of drug reinforcement in animal models (Orsini et al., 2004).

Converging evidence suggests further that an enhanced stimulant response to one of these drugs—alcohol or amphetamine—is associated with vulnerability to abuse the other substance. Men with a family history of alcoholism exhibit a heightened sensitivity to the subjective stimulant effects of amphetamine (Gabbay, 2005). Stimulant users manifest an exaggerated physiological response to alcohol (Brunelle et al., 2006), as compared to individuals who have never used psychostimulant drugs. Conversely, moderate alcohol drinkers report greater stimulation to amphetamine than light drinkers (Stanley et al., 2011; Stoops et al., 2003). This association is also evident in rodent models: Selectively bred rats that self-administer alcohol display a heightened responsiveness to the stimulant effects of amphetamine (D’Aquila et al., 2002; Fahlke et al., 1995; McKinzie et al., 2002), as compared to non-preferring rats. The relationship between the stimulant response and vulnerability may be even broader: Individuals who consistently choose alcohol over placebo in the laboratory report greater stimulant effects of alcohol as well as heavier marijuana use (de Wit et al., 1987). Whereas these findings suggest that the stimulant response is related to risk more generally, the evidence bearing on this question is limited. In particular, no study has assessed the relationship between amphetamine-induced stimulation and multiple continuous measures of alcohol and drug use.

Negative Emotionality

A second factor implicated in relation to alcohol and drug use is negative emotionality (Chassin et al., 2004; Elkins et al., 2006; Hicks et al., 2012; Krueger, 1999; Loukas et al., 2000; Sher et al., 2005). Negative emotionality refers to the tendency to experience heightened negative affect and to perceive the world as threatening, stressful, and problematic (Watson and Clark, 1984). Individuals who score high on measures of negative emotionality are susceptible to relatively frequent and intense aversive emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger) and report elevated baseline distreses even in the absence of external stressors (Tellegen and Waller, 2008; Watson and Clark, 1984).

Negative emotionality and related constructs (e.g., neuroticism) are associated with substance use in a range of clinical and community samples. Diverse assessment methods yield higher scores on measures of these traits among individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders (Jackson and Sher, 2003; Martin et al., 2000; McCormick et al., 1998; McGue et al., 1997, 1999; Sher et al., 2005; Swendsen et al., 2002) as well as polysubstance abusers (McCormick et al., 1998). Beyond its effect on consumption, negative emotionality is related to an increased incidence of alcohol-related harmful behavior (Isaak et al., 2011) and substance use problems (James and Taylor, 2007; Ruiz et al., 2003). Evidence from some longitudinal studies suggests further that negative emotionality is predictive of later substance abuse and dependence (Caspi et al., 1997; Chassin at al., 2004; Elkins et al., 2006; Galéra et al., 2010; Hicks et al., 2012; Measelle et al., 2006; Welch and Poulton, 2009).

The relationship between negative affect and substance use is most often interpreted in terms of negative reinforcement. That is, persistent negative emotions may promote substance use as a means to dampen or, more broadly, to escape or avoid these undesirable states (Carmody, 1992; Gonzalez et al., 2011; Greeley and Oei, 1999; Sher et al., 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2007). However, there is also evidence to support a distinct pathway that can be characterized in terms of positive reinforcement: Emotion-based dysregulation may promote behavior that leads to immediate reward, including risky alcohol and drug use, without regard for potential longer-term negative outcomes (Baumeister and Scher, 1988; Jackson, 1984; Wallace et al., 1991; cf. Urgency, Cyders and Smith, 2008; Tiffany, 1990; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001). That is, negative affect may disrupt efforts to override impulsive behavior (Cheetham et al., 2010). This positive reinforcement pathway has received considerably less empirical attention than that involving negative reinforcement. In particular, no study has addressed the potential moderating effect of sensitivity to the rewarding effects of drugs on the relationship between negative emotionality and problematic substance use.

Current Study

The purpose of the present analysis was threefold: We sought to extend current research by evaluating the relationship between the response to amphetamine and multiple continuous measures of alcohol and drug use and by assessing the relationship between negative emotionality and substance use in a large, healthy sample. Finally and importantly, we sought to determine if the response to amphetamine and negative emotionality interactively predict measures of substance use, including quantity and frequency measures of alcohol use and a categorical measure of illicit drug use. To the extent that negative emotion drives dysregulation, thereby promoting reward-seeking, its effect on substance use may be moderated by sensitivity to drug reward.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Volunteers aged 18 to 25 years old were recruited for an event-related potential (ERP) study in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. Data analyzed for the present report were collected in a separate session, conducted at least two days prior to those in which ERPs were recorded. Healthy young women (n = 99) and men (n = 93) completed this session, in which the subjective effects of 10 mg d-amphetamine were evaluated. Written informed consent was obtained from participants, and compensation was provided for all phases of participation. The research protocol was approved by the Uniformed Services University Institutional Review Board.

Screening

A two-stage screening process was used to determine eligibility for the study. First, interested individuals completed an online survey developed in our laboratory and hosted on a secure web site (Datstat, Inc., Seattle, WA). The survey comprised questions on demographics, medical conditions, medication use, lifestyle, and general health, the purpose of which was to identify individuals meeting preliminary exclusion criteria. As a safety precaution, those weighing 20% above or 10% below the average for their height and sex, as well as those weighing more than 220 pounds (99.8 kg), were excluded. Individuals smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day and those likely to experience nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Fagerstrom, 1978) during the 4.5-h experimental sessions were also excluded. Individuals taking prescription medications that could interact with amphetamine were excluded at this point (unless the prescription use was to be short-term), as were those who reported having taken psychotropic medication for any psychiatric disorder. The survey also excluded women who were pregnant, nursing, or planning to become pregnant.

Eligible individuals completed the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen, 1982) and were invited to the laboratory for further screening. At that appointment, a computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (C-DIS; Robins et al., 1995) was administered to all candidates; those with current or past DSM-IV Axis I disorders, including alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence disorders, were excluded. Exceptions were made for tobacco use disorder (as described above, exclusions were based instead on Fagerstrom score) and for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavior disorders.1 An exception was also made for depressive disorder with an exogenous precipitant (e.g., death of a loved one, job loss), when the depressive episode had occurred more than six months prior.

A resting electrocardiogram was performed, and a blood sample was collected for health screening. A nurse practitioner conducted physical examinations of qualified individuals to confirm the absence of medical conditions that would contraindicate amphetamine. During this visit, participants also completed a shortened version of the Department of Defense (DOD) Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Military Personnel (Bray et al., 2003).

Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire

The MPQ, a 276-item self-report inventory, was used to assess negative emotionality. The factor-analytically derived MPQ scales represent 11 primary personality dimensions; ten of these scales load on three orthogonal higher-order traits. The higher-order factor Negative Emotionality (NEM), used in the present study, reflects variation in the primary scales of Aggression (vindictive, victimizes others to own advantage), Stress Reaction (nervous, emotionally labile, irritable), and Alienation (feels mistreated, maligned). The internal consistencies of the MPQ range from .76 to .89, and one-month retest reliabilities range from .82 to .92 (Tellegen, 1982).

Survey of Health-Related Behaviors

A subset of questions drawn from the DOD Survey of Health Related Behaviors (Bray et al., 2003) assessed alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. Three measures of alcohol use were calculated: (a) average daily alcohol consumption, which reflects typical drinking as well as atypical heavy drinking (i.e., a day when eight or more standard drinks were consumed) and which is weighted to account for the ethanol content of beer, wine, and liquor; (b) number of days out of the past 30 on which the participant drank five or more bottles, cans, glasses, or drinks of either beer, wine, or liquor (i.e., binge-drank); and (c) number of days in the past year on which they drank a sufficient amount to “feel drunk” (i.e., were intoxicated) (see Bray et al., 2003 for more details).

If applicable, participants also reported the age at first regular use of alcohol (i.e., at least once a month), as well as the onset age of regular cigarette use (i.e., one a day for a week or longer), the average number of cigarettes smoked per day in the past 30 days, and their most recent smoking occasion. Additionally, participants reported the number of times they used any illicit drug (marijuana, PCP, LSD, cocaine, amphetamines, tranquilizers, barbiturates, heroin, analgesics, inhalants, “designer” drugs, anabolic steroids, GHB) in the past 30 days and in the past year, as well as the most recent occasion of use.

Participants who reported consuming 0.0 oz of ethanol on average per day were considered abstainers; those who reported never having used tobacco or any illicit drug were considered non-users, separately for each of these two categories.

Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale

Stimulant and sedative effects of d-amphetamine were recorded using the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES), a 14-item self-report instrument designed to assess subjective effects of alcohol (Earleywine, 1994; Martin et al., 1993). The BAES provides scores on two internally consistent subscales (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85 – 0.94): a seven-item stimulant scale (elated, energized, euphoric, excited, rapid thoughts, stimulated, vigorous) and a seven-item sedative scale (difficulty concentrating, down, heavy head, inactive, sedated, slow thoughts, sluggish) (Martin et al., 1993). Participants describe how they are feeling, using a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) for each of the items.

Previous research has used the BAES Stimulant scale to assess the subjective effects of d-amphetamine (e.g., Hutchison and Swift, 1999; Hutchison et al., 1999). This scale has differentiated individuals with and without a family history of alcoholism based on their response to alcohol (Erblich et al., 2003) and amphetamine (Gabbay, 2005) and has revealed a modest correlation between the effects of 20-mg d-amphetamine and those of alcohol (Holdstock and de Wit, 2001). The rationale of the present study derives in part from an empirical association between response to the stimulant effects of alcohol and other drugs and use of those substances. Moreover, as sedation is not a typical effect of amphetamine, it is likely of limited relevance to understanding relations between the amphetamine response and substance use. Accordingly, this report focuses on the Stimulant scale of the BAES.

Experimental Session

Overview

After screening was complete, eligible individuals were invited to participate in a 4.5-h laboratory session to evaluate the subjective effects of 10-mg d-amphetamine.

Preliminary procedures

Participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol and to consume their usual amount of caffeine and tobacco in the 24 hours prior to the session and to eat a light breakfast before arriving at the laboratory. To avoid possible hormonal effects on amphetamine response (Justice and de Wit, 1999; White et al., 2002), all sessions were held in the late menstrual-early follicular phase of each woman’s cycle (i.e., within an eight-day window beginning two days after the onset of menses). At the beginning of each session, a breath sample confirmed that breath alcohol concentration was 0.00% (Dräger Alcotest 6510 Breathmeter; Dräger Safety Diagnostics, Inc., Irving, TX) and a urine specimen was tested for the presence of marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines, PCP, and opiates (Varian OnTraK TesTcup; Varian, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Out of 206 participants, 14 were excluded as a result of a positive drug test; there were no positive breath alcohol tests. Women also provided a urine sample for pregnancy testing; no positive results were obtained. Participants answered a brief set of questions about recent drug use, food consumption, exercise, sleep, and exposure to stress, to ensure that there were no circumstances that could affect amphetamine response. No sessions were rescheduled and no one was excluded on the basis of these questions.

Amphetamine challenge

Immediately after these procedures, participants completed the baseline BAES. A capsule containing 10-mg d-amphetamine was then administered orally with 8 oz of water. In healthy individuals, 10-mg d-amphetamine results in an average blood level of 29.2 ng/ml (Drug Information Portal, 2011). The drug undergoes rapid absorption, producing this peak level within two to four hours after ingestion (de la Torre et al., 2004).

The decision not to include a placebo session arose from exploratory analyses of data collected in a previous study, in which 10-mg d-amphetamine and a placebo were administered in separate sessions. These analyses suggested that responder groups based on drug – baseline change scores (as in the present study) differed on several measures of alcohol use; and further, that responder groups based on drug – placebo comparisons differed similarly on the same measures (FHG, unpublished data). Thus, in the current study, we elected to define groups in a single session (i.e., using drug – baseline change scores). To minimize the effects of expectancies on the subjective response, participants were told that the capsule contained one of the following substances: (a) cold medication, (b) an anti-anxiety agent, (c) a drug used in sleep disorders, (d) a mood stabilizer, (e) caffeine, or (f) a placebo.

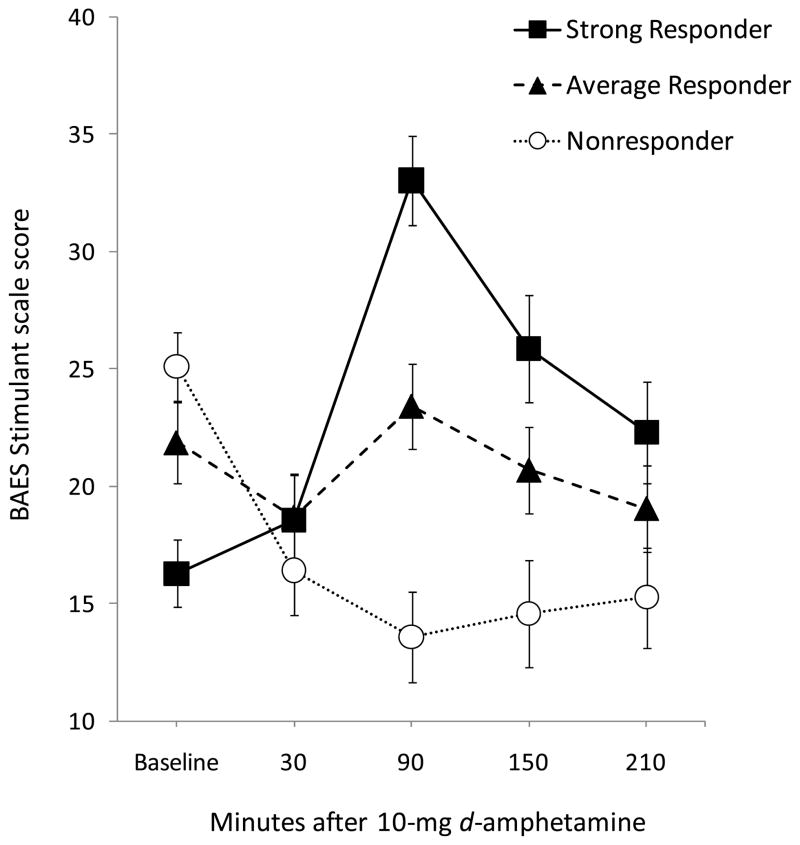

Participants were then instructed to relax or engage in quiet activity (e.g., reading, watching videos) while seated in a comfortably furnished room. They completed the BAES four more times: .5 h, 1.5 h, 2.5 h, and 3.5 h after capsule administration. The timing of assessments considered the time course of mean scores on the BAES Stimulant scale obtained in our laboratory in past studies using 10 mg d-amphetamine, as well as the need to repeat other tests at regular intervals in the same session (results not reported in this paper). The subjective stimulant response (Stim) was calculated by subtracting baseline Stimulant scores from those obtained 1.5 h after amphetamine (i.e., time of the mean peak effect) (see Figure 1). Vital signs were assessed before and at regular intervals after capsule ingestion. A light lunch was provided 40 m after the capsule, and a granola bar was consumed 2 h later. At the end of the session, participants were picked up by a friend or family member or provided a taxi.

Fig. 1.

Mean ratings on the BAES Stimulant scale assessed before and four times after 10-mg d-amphetamine, for three responder groups, defined using tertiles of the distribution of change scores on this scale (Stim = 1.5 h – baseline): Responders, change score ≥ 7, n = 63; Average Responders, change score > −4 and < 7, n = 64; Nonresponders, change score ≤ −4, n = 65. By definition, the groups exhibited distinct stimulant responses to amphetamine, and the differences were most evident at 1.5 h post-drug. Note that this figure is presented for illustrative purposes, to convey the magnitude of and variation in the stimulant response. In the statistical analyses, Stim was treated as a continuous predictor variable. BAES = Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale.

Data Analysis

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to determine the effects of each predictor variable (i.e., gender, Stim, NEM, and Stim × NEM) on the quantitative measures of alcohol use: (a) average daily alcohol consumption; (b) frequency of binge drinking in the past month; (c) frequency of alcohol intoxication in the past year; and (d) age of onset of regular alcohol use. Due to the strong positive skew of our dependent variables, square root transformations (anchored at the constant value 1) were applied to the dependent variables prior to estimating the regression models in order to improve the linearity of their relationship with the predictors (Miranda, 2000). To correct for non-normality in the regression residuals, nonparametric percentile bootstrapping (2,000 iterations) was performed to evaluate the significance values associated with each predictor.

For the first three alcohol variables (average daily consumption, binge drinking frequency, and intoxication frequency), the model was evaluated in current drinkers only (i.e., individuals who indicated using alcohol at least once in the past month; N = 160). For age of onset of regular drinking, the model was evaluated in individuals who reported regular alcohol use (i.e., at least once a month; N = 144). There were too few reports of illicit drug use to analyze quantitative measures of that variable.

Hierarchical binary logistic regressions were used to evaluate the relationship between the same set of predictor variables and user status (user vs. non-user) for alcohol and, separately, any illicit drug (including marijuana). The sample comprised too few regular smokers (i.e., once a day for a week or longer; n = 20) to analyze tobacco use variables.

First, bivariate correlations among the independent and dependent variables were computed. Next, the same four-step model was tested for each substance use variable. As order of entry of predictors can affect the outcome of hierarchical regression, we determined order on the basis of theoretical and statistical considerations. It is essential to enter main effects before entering an interaction, to allow evaluation of the extent to which the interaction accounts for variance in the dependent measures after taking into account the main effects of each predictor (Tabachnick and Fidell, 1989). Gender was entered into the model first due to its well-established association with drinking and drug use (Brady and Randall, 1999); Stim was entered next, as it was the primary focus of this study; NEM was entered next, in order to evaluate its effects controlling for Stim; and the Stim × NEM interaction term was then entered in the final step. To determine the unique contribution of each predictor variable to the predictive value of the models, the increment in R2 following the introduction of that variable into the model was tested for significance. The beta weight of each predictor was evaluated using the p value associated with the confidence interval obtained by bootstrapping. For logistic models, the χ2 at each step of entry was interpreted. The predictive value of the final model for each variable is also reported.

The Johnson-Neyman procedure (Aiken and West, 1991; Preacher et al., 2006) was employed to probe significant interactions (MODPROBE macro; Hayes and Matthes, 2009). This technique, in combination with bootstrapping, was used to derive the value of Stim at which the effect of NEM was significant at the p = .05 level, separately for each quantitative measure of alcohol use. Consistent with our regression analyses, gender was included as a covariate in each model.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS/PASW 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). There was one participant with incomplete drug use data.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The mean (± SD) age of the participants included in these analyses was 20.5 years (1.9); the mean body mass index was 23.3 (2.8); and the mean years of education was 14.5 (1.5). Of the 192 participants, 187 (97.4%) were never married, one (.5%) was married, two (1.0%) were divorced, and two (1.0%) were currently living with a partner. In the online survey, 104 participants (54.2%) identified as non-Hispanic White, 36 (18.8%) as Black, 20 (10.4%) as Asian, 11 (5.7%) as Hispanic, 11 (5.7%) as multiracial, one (.5%) as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and nine (4.7%) chose not to identify.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the four continuous and two binary measures of substance use.

Table 1.

Alcohol and Drug Use Descriptive Statistics

| Criterion variable | Full sample (N = 192) |

|---|---|

| Average daily alcohol consumption (ounces ethanol; M, SD) | 0.5 (0.7) |

| Episodes of binge drinking in past month (M, SD) | 1.5 (2.6) |

| Episodes of intoxication in past year (M, SD) | 18.4 (32.2) |

| Age of onset of regular alcohol usea (M, SD) | 18.2 (2.0) |

| Ever consumed alcohol (%) | 83.3 |

| Ever consumed an illicit substanceb (%) | 46.1 |

At least once a month

Includes marijuana, PCP, LSD, cocaine, amphetamines, tranquilizers, barbiturates, heroin, analgesics, inhalants, designer drugs, steroids, and GHB.

Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale

As noted above, we calculated a change score (Stim) for each participant on the Stimulant scale of the BAES (1.5 h – baseline), and Stim was treated as a continuous predictor variable in the statistical analyses. However, for the purposes of illustrating the magnitude and variability of the response, Figure 1 depicts mean scores on that scale, before and four times after 10-mg d-amphetamine, for three responder groups. The groups represent the three tertiles of the distribution of change scores.

Over all of the participants, the mean (± SD) change in ratings on the Stimulant scale (e.g., energetic and elated) from baseline to peak (1.5 h) was 2.1 (14.0), and change scores ranged from −47 (i.e., a paradoxical decrease in ratings of stimulation after amphetamine) to 58.

Bivariate Correlations

Zero-order Pearson’s correlations among the predictor and criterion variables are reported for the full sample in Table 2. These analyses reveal the strength of the individual linear relationships between gender, Stim, NEM and substance use. The interaction term Stim × NEM is not included because its correlation with the dependent variables is greatly influenced by scaling of the main effects.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations between Predictor Variables and Measures of Substance Use

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gendera | — | |||||||

| 2. Stim | .025 | — | ||||||

| 3. NEM | .062 | .022 | — | |||||

| 4. Average daily alcohol consumption (N = 192) | .168* | .100 | .136 | — | ||||

| 5. Frequency of binge drinking (N = 192) | .210** | .074 | .083 | .792** | — | |||

| 6. Frequency of intoxication (N = 192) | .118 | .101 | .084 | .805** | .714** | — | ||

| 7. Age of onset of regular alcohol use (N = 144) | −.134 | −.183* | −.050 | −.164* | −.138 | −.142 | — | |

| 8. Alcohol drinker: yes/no (N = 192) | −.042 | .138 | −.011 | .346** | .302** | .372** | .034 | — |

| 9. Illicit substance user: yes/no (N = 191) | .097 | .168* | −.045 | .311** | .293** | .356** | −.037 | .321** |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Female = 0, Male = 1

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01

Hierarchical Binary Logistic Regression Analyses of Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use

The results of the logistic regression analyses are presented in Tables 3a and 3b. These analyses evaluated the contributions of the same four predictors—gender, Stim, NEM, and the Stim × NEM interaction—to the prediction of categorical measures of substance use (i.e., whether individuals had ever used alcohol or, separately, illicit drugs). Statistics of interest in these analyses include the significance associated with the chi-square value (indicating model fit) and the significance of the beta value of each predictor at its step of entry (indicating its relative contribution).

Table 3a.

Logistic Regression Statistics: Alcohol User Status (N = 192)

| Predictor | Step χ2 | p | Model χ2 (df) | p | Standardized β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. Gender | 0.34 | .561 | 0.39 (1) | .561 | 1.253 | .562 |

| Step 2. Stim | 3.82 | .051 | 4.16 (2) | .125 | 1.029 | .058 |

| Step 3. NEM | 0.00 | .984 | 4.16 (3) | .245 | 1.000 | .984 |

| Step 4. Stim × NEM | 0.12 | .733 | 4.27 (4) | .370 | 1.000 | .735 |

| Final R2 | 0.04 |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Table 3b.

Logistic Regression Statistics: Illicit Drug User Status (N = 191)

| Predictor | Step χ2 | p | Model χ2 (df) | p | Standardized β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. Gender | 1.80 | .180 | 1.80 (1) | .180 | 0.677 | .181 |

| Step 2. Stim | 5.38 | .020 | 7.72 (2) | .028 | 1.025 | .025 |

| Step 3. NEM | 0.62 | .431 | 7.80 (3) | .050 | 0.993 | .432 |

| Step 4. Stim × NEM | 0.54 | .085 | 8.17 (4) | .085 | 1.000 | .550 |

| Final R2 | 0.06 |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Alcohol Use (N = 192)

Controlling for gender, Stim reached trend-level significance as a predictor of ever having drunk alcohol (χ2 = 3.82, p = .051), although the final model was non-significant.

Illicit Drug Use (N = 191)

The entry of Stim at the second step improved the prediction of ever having used an illicit drug (χ2 = 5.38, p = .020) to the extent that the two-step model (gender, Stim) significantly predicted substance use (χ2 = 7.72, p = .028). None of the remaining predictor variables improved the model, but the model remained significant at the third step (i.e., after entry of NEM; χ2 = 7.80, p = .050).

Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regression Analyses of Alcohol Use

Linear regression analysis provides a means of evaluating the contribution of a set of predictor variables to variance in the dependent, or criterion, variable. These analyses derive a significance level (p value) associated with the following statistics: (a) the F value at the step of entry of each predictor, which indicates whether the model explains some portion of outcome variance; (b) the increments in R2 following the introduction of each predictor variable, which addresses the question of whether that variable adds to the predictive utility of the model, beyond the contribution of the predictors entered before it; and (c) the beta of each predictor at its step of entry, which represents whether the predictor contributes significantly to the regression model.

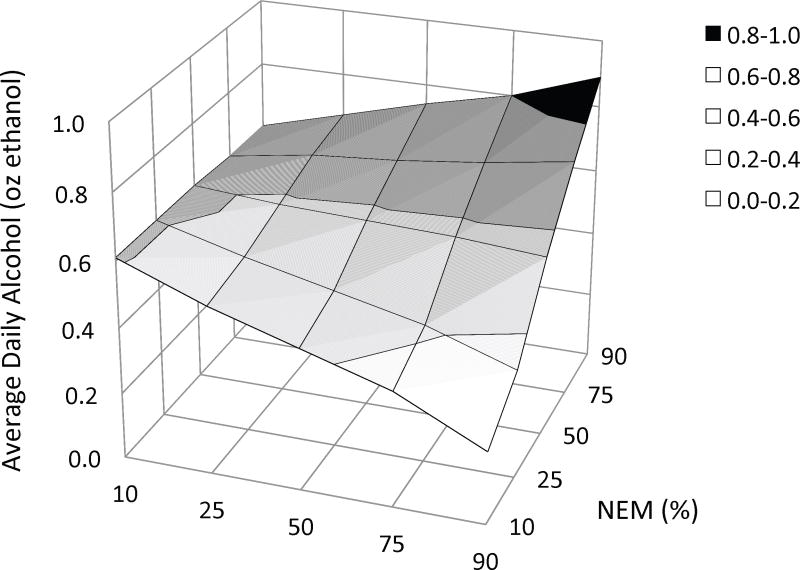

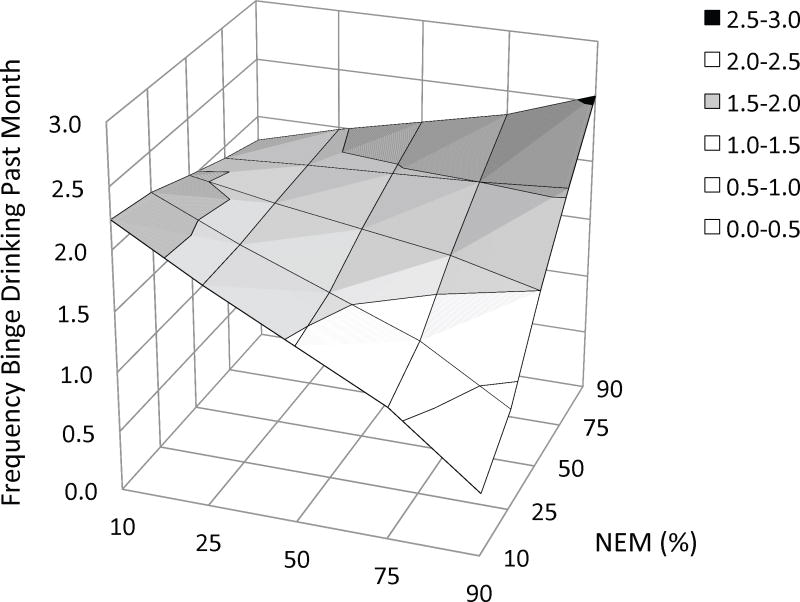

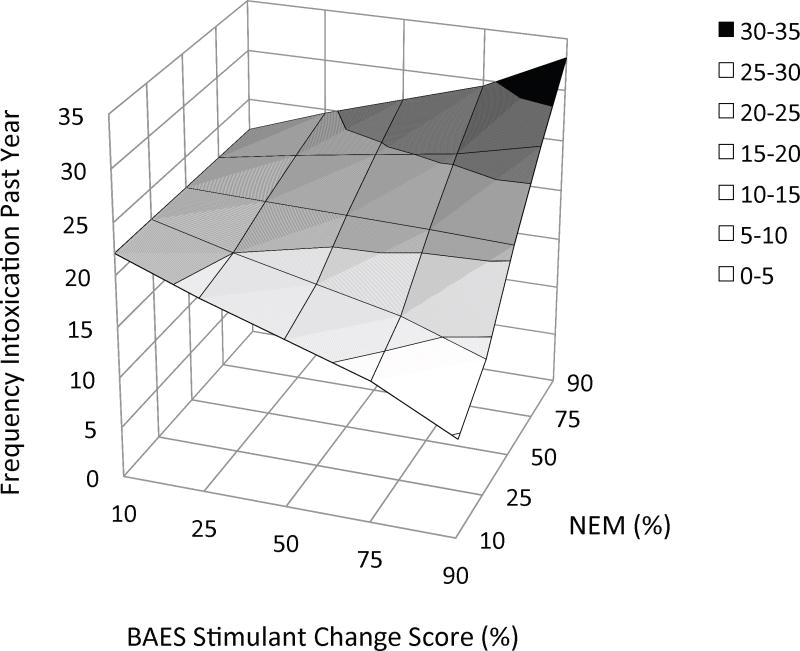

In the present study, the linear regression analyses evaluated the contributions of gender, Stim, NEM, and the interaction between the latter two predictors (a total of four steps) to variability in quantitative measures. The results of these analyses are presented in Tables 4a – 4d. To clarify significant Stim × NEM interactions, Figures 2a – 2c depict the hyperplane derived from regressing Stim and NEM on each measure of alcohol use (while controlling for gender).

Table 4a.

Linear Regression Statistics: Average Daily Alcohol Consumption (N = 160)

| Predictor | ΔR2 | p | Model F (df) | p | Standardized β | Bootstrapped p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. Gender | 0.045 | .007 | 7.519 (1, 158) | .007 | 0.212 | .020 |

| Step 2. Stim | 0.002 | .522 | 3.951 (2, 157) | .021 | −0.043 | .710 |

| Step 3. NEM | 0.020 | .070 | 3.780 (3, 156) | .012 | 0.147 | .102 |

| Step 4. Stim × NEM | 0.034 | .017 | 4.368 (4, 155) | .005 | 0.203 | .020 |

| Final R2 | 0.101 |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Table 4d.

Linear Regression Statistics: Age of Onset of Regular Alcohol Usea (N = 144)

| Predictor | ΔR2 | p | Model F (df) | p | Standardized β | Bootstrapped p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. Gender | 0.001 | .700 | 0.149 (1, 142) | .700 | −0.032 | .876 |

| Step 2. Stim | 0.049 | .020 | 2.860 (2, 141) | .062 | −0.209 | .158 |

| Step 3. NEM | 0.009 | .323 | 2.235 (3, 140) | .088 | −0.096 | .421 |

| Step 4. Stim × NEM | 0.000 | .890 | 1.666 (4, 139) | .163 | −0.015 | .876 |

| Final R2 | 0.050 |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

At least once a month

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional plots of the relationship between three measures of alcohol use and the combination of stimulant response and negative emotionality, as derived from multiple linear regression. In each figure the criterion variable is plotted on the Y-axis: (a) average daily alcohol intake, (b) frequency of binge drinking, and (c) frequency of intoxication. Values on the X-axes represent the percentile ranking of the change in BAES Stimulant scale score (90 m postdrug – baseline) and values on the Z-axes represent the percentile ranking of NEM score. Thus, the effect of NEM on each measure of alcohol use is depicted at different levels of the amphetamine response along the Z-axis. The figures suggest that the amphetamine response has a moderating effect on the relationship between negative emotionality and these measures. Alcohol use is little affected by negative emotionality for subjects with a blunted response to amphetamine (left side of the hyperplane). In contrast, among subjects with a stimulant response to this low dose of amphetamine, alcohol use increases as negative emotionality increases (right side of the hyperplane). Threshold change scores, above which this relationship reaches statistical significance, were provided by Johnson-Neyman post hoc analyses: (a) daily intake: 2.5 [52%]; (b) binge drinking: 10.6 [77%]; and (c) intoxication: 12.8 [82%]. BAES = Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale; MPQ NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Average Daily Alcohol Consumption (N = 160)

The final four-step model explained 10.1% of the variance in average daily alcohol consumption (adjusted R2 = .078, F(4, 155) = 4.368, p = .005). Male gender accounted for a significant portion of the variance (ΔR2 = .045, bootstrapped p = .020). The addition of Stim at Step 2 and NEM at Step 3 did not significantly increase the proportion of variance explained in daily alcohol consumption. However, the introduction of the interaction term (Stim × NEM) significantly improved the model (ΔR2 = .034, bootstrapped p = .020). Figure 2a depicts the effects of this interaction on daily consumption.

Johnson-Neyman post hoc analysis determined that the positive relationship between NEM and daily alcohol use reaches statistical significance when Stim ≥ 2.5 (.41 points below the mean or .028 SD). That is, an increase in self-reported stimulation of at least 2.5 points from baseline was requisite for the relationship between NEM and average daily alcohol use to manifest.

Frequency of Binge Drinking in the Past Month (N = 160)

The same four predictors explained 10.6% of the variance in binge-drinking frequency (adjusted R2 = .083, F(4, 155 = 4.577, p = .002). As for daily consumption, male gender accounted for a significant portion of the variance in binge drinking (ΔR2 = .066, bootstrapped p = .009). Also consistent with the results for daily consumption, Stim × NEM improved the ability of the model to predict the frequency of binge drinking (ΔR2 = .034, bootstrapped p = .014), whereas Stim and NEM alone did not. The interaction is plotted in Figure 2b.

Post-hoc analysis indicated that NEM was positively related to binge drinking when Stim ≥ 10.6 (7.69 points above the mean or .729 SD)

Frequency of Intoxication in the Past Year (N = 160)

The model also explained 5.9% of the variance in intoxication frequency (adjusted R2 = .035, F(4, 155 = 2.451, p = .048). In contrast with the results for the other quantitative measures of alcohol use, male gender only reached trend-level significance as a predictor after bootstrapping (ΔR2 = .026, bootstrapped p = .085), whereas the Stim × NEM interaction was a significant predictor (ΔR2 = .024, bootstrapped p =.017). Figure 2c depicts the Stim × NEM interaction for intoxication frequency.

Post hoc analysis indicated that NEM was associated with more frequent intoxication when Stim ≥ 12.8 (9.89 points above the mean or .88 SD).

Onset Age of Regular Alcohol Use (≥ one occasion per month; N = 144)

The same four predictors were regressed on age of onset of monthly alcohol use for the subset of participants who reported regular alcohol use. This model approached significance at the second step, with the entry of Stim (F(2, 141) = 2.860, p = .062): Higher Stim scores were related to initiation of regular use at a younger age (ΔR2 = .049, p = .020). However, the p value associated with the bootstrapped beta of Stim did not reach significance in this two-factor model (bootstrapped p = .158).

DISCUSSION

Response to the stimulant effects of alcohol is associated with risk for alcoholism. A smaller body of research suggests the subjective response to amphetamine is similarly related to risk. Additionally, substantial evidence implicates negative emotionality in the etiology of alcohol use disorders. To the extent that this personality trait affects risk through a positive reinforcement pathway, promoting reward-seeking behavior, these factors may interact to affect individual differences in alcohol use.

Consistent with this idea, the present study demonstrated associations between negative emotionality and alcohol use only among individuals who reported an increase in stimulation after this low dose of amphetamine. In particular, in regression models, negative emotionality in combination with a robust amphetamine response predicted greater average daily alcohol intake, more episodes of binge drinking, and more frequent intoxication. In contrast, among individuals with a blunted increase or a paradoxical decrease in stimulation after amphetamine, negative emotionality was not associated with alcohol use.

The study also produced some evidence of an independent effect of the amphetamine response: In logistic regression models, the amphetamine response predicted illicit drug use, and a statistical trend suggested that it also predicted alcohol use. Bivariate correlations revealed an association between a strong amphetamine response and initiation of regular drinking at a younger age, although this relationship did not reach statistical significance when controlling for other factors in our regression model. Finally, consistent with some previous work, negative emotionality did not independently predict any measure of substance use.

Amphetamine Challenge as a Measure of the Stimulant Response

In the present study, in combination with a tendency to experience negative emotions, the response to amphetamine was associated with risky alcohol use. This finding is consistent with the argument that there are commonalities in response to the stimulant effects of various drugs (Wise and Bozarth, 1987). Indeed, substantial evidence implicates the mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathway as a mediator of the reinforcing effects of various drugs of abuse (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Volkow et al., 2002; 2007; 2009; Wise and Bozarth, 1987). Thus, associations between the amphetamine response and alcohol use may reflect a common element, shared between the response to amphetamine and that to the stimulant effects of alcohol and mediated in part by mesocorticolimbic dopamine function.

In this view, individuals who have an enhanced amphetamine response are also likely to exhibit a robust response to the stimulant effects of alcohol. Only two studies have examined the response to amphetamine and that to alcohol in the same subjects. In one of these, self-reports of the stimulant effects of 20-mg d-amphetamine (but not those of a 10-mg dose) correlated with those of alcohol (Holdstock and de Wit, 2001). In a second study (Stoops et al., 2003), the response to 5-mg/kg ethanol predicted response to 15-mg d-amphetamine. Animal studies also provide some support for interpreting the observed associations in terms of commonalities in the stimulant response: Mice sensitive to methamphetamine-induced locomotor stimulation also exhibit an enhanced response to alcohol (Kamens et al., 2006).

An alternative or additional explanation of the relationship between the amphetamine response and alcohol use is also plausible: The association may reflect the effects of other traits that co-occur with a stimulant response, such as reward sensitivity (Brunelle et al., 2004; Flagel et al., 2010; White et al., 2006), novelty- or sensation-seeking (Bevins and Peterson, 2004; de Wit et al., 1987; Gingras and Cools, 1996; Hutchison et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2006, 2009; Piazza et al., 1989; Orsini et al., 2004; Ray et al., 2006; Stoops et al., 2007), and impulsivity (Buckholtz et al., 2010; Kelly et al., 2006; Ray et al., 2006; Stanis et al., 2008).

As these traits are themselves considered risk factors for substance use and misuse (Iacono et al., 2008; Màsse and Tremblay, 1997; Wong et al., 2006), the subjective response to amphetamine may be a marker of vulnerability due in part to its covariance with them. That is, individuals with a strong amphetamine response may be at elevated risk for substance use in part by virtue of personality traits that have been empirically associated with the stimulant response. As the present analyses did not evaluate these traits, their relative predictive utility, as compared to the amphetamine response, remains to be determined.

Notably, in the present study, the amphetamine response independently predicted (in regression models) ever having used an illicit drug. However, more than 80% of the participants who indicated that they had used an illicit drug reported using only marijuana. As the effects of marijuana are not primarily stimulant, this finding is less readily explained in terms of commonalities in the stimulant response to various drugs and may be more effectively interpreted in terms of correlated personality traits.

Combined Effects of the Stimulant Response and Negative Emotionality

Regardless of the mechanism underlying the relationship between the amphetamine response and alcohol use, the association was evident only in combination with negative emotionality. It has been proposed that individuals who are prone to experience negative affect drink alcohol for its negative affect-dampening properties (Greeley and Oei, 1999; Sher et al., 2005). However, the anxiolytic effects of alcohol and other drugs are distinct from their stimulant effects. Thus, the finding of an interaction between responsivity to the stimulant effects of amphetamine and negative emotionality is not readily explained in terms of simple self-medication hypotheses.

A growing body of research considers the effect of negative emotion on substance use more broadly. Individuals who experience frequent and intense negative emotions may attempt to regulate, escape, or avoid these undesirable affective states (Gonzalez et al., 2011). Some work suggests that negative emotions promote impulsive action, disrupting control and biasing behavioral decisions in favor of those that lead to immediate reward (Baumeister and Scher, 1988; Cyders and Smith, 2008; Gonzalez et al., 2011). Insofar as negative affect encourages the pursuit of reward, individuals who experience frequent negative emotions and who are also susceptible to drug reinforcement may be more inclined than others to seek that reward in the form of drugs and alcohol.

Moreover, as proposed above, individuals with an enhanced amphetamine response may also tend to be impulsive or to seek novel experiences. As such, these individuals may be more vulnerable to the disruptions in control triggered by negative affect. In this context it is notable that, in a longitudinal study, individuals with high levels of negative emotionality and behavioral disinhibition, a trait that shares elements in common with those that have been associated with the stimulant response, were at particularly high risk for alcoholism (McGue et al., 1997).

The results suggested further that negative emotionality is not associated with excessive alcohol use in the absence of sensitivity to drug-based reward. When negative affect leads to dysregulation, individuals insensitive to the stimulant effects of drugs may seek rewards other than those associated with alcohol and drugs. Thus, when behavior is dysregulated by negative affect, relative resilience to drug reward may be a protective factor.

Finally and surprisingly, a robust amphetamine response that occurred together with low negative emotionality appeared to be associated with limited alcohol use (see Figures 2a – 2c). Individuals who exhibit an enhanced stimulant response but who are not prone to negative affect may share some common protective factor, a possibility that warrants further study.

The Stimulant Response as an Independent Predictor

In this study, maladaptive patterns of alcohol use, including heavy intake, binge-drinking, and drinking to intoxication, reflected the effects of a strong amphetamine response combined with negative emotionality. In contrast, the amphetamine response independently predicted the bivariate measure of illicit drug use in logistic regression models, and there was a trend for it to predict alcohol use. The different patterns of results for these two sets of variables suggest that the phenotypes have distinct etiologies. Risky alcohol use may be associated with sensitivity to the stimulant effects of drugs only in the presence of frequent and intense negative emotions that motivate reward seeking. By comparison, negative emotionality does not appear to be a precondition for having used alcohol or an illicit drug, which are comparatively innocuous behaviors. Rather, these phenotypes may reflect susceptibility to the reinforcing effects of alcohol and drugs and/or the effects of personality traits that co-occur with a stimulant response. Having used an illicit drug, for example, may reflect a tendency to seek novel experiences.

Negative Emotionality as an Independent Predictor

Negative emotionality alone did not predict any measure of substance use in this healthy sample. Thus, the results are somewhat consistent with prior research linking negative emotionality to problematic alcohol use (Isaak et al., 2011; James and Taylor, 2007; Ruiz et al., 2003), but extend that work by suggesting that individual differences in this dimension of personality interact with variability in the stimulant response to affect the development of problematic drinking.

Further, our findings may address conflicting findings in the prior literature, as they suggest that negative emotionality works in concert with other, unmeasured factors to affect risk. To the extent that this is the case, concurrent evaluation of other risk factors, including drug response, may help to resolve inconsistencies regarding the relationship between negative emotionality and maladaptive alcohol use.

Limitations

The present study was limited in several ways. First, individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for alcohol or other substance use disorders were excluded. Other exclusion criteria, necessary to control for potential confounding variables in the ERP study, further increased the homogeneity of the study sample. Accordingly, the findings address variation in alcohol and drug use in a healthy sample. Future work must evaluate the effects of these variables in samples that include individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders and, more generally, in studies with less stringent exclusion criteria.

This study revealed an association between the amphetamine response and a categorical measure of ever having used an illicit drug. However, the sample provided inadequate power to evaluate separate predictive models for individual drugs other than alcohol. Similarly, it was not possible to evaluate the model for quantitative measures of substance use other than alcohol. Thus, further studies are needed to assess the association between the stimulant response and tobacco and illicit drug use.

Further limiting interpretation, the cross-sectional study design prohibits conclusions about the direction of causation. Alcohol and other substance use may sensitize individuals to the stimulant effects of amphetamine (Stoops et al., 2003) and/or increase negative emotionality (Schuckit, 1983, 1986; Sher et al., 2005; Sher and Trull, 1994). With one notable exception in which an enhanced stimulant response to alcohol predicted heavier alcohol use two years later (King et al., 2011), previous studies have also employed a cross-sectional design. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine if the amphetamine response, negative emotionality, or their interaction predict the development of substance use.

Another important limitation of the present study is that it did not include a placebo condition. As described in Materials and Methods, data collected in an earlier study suggest this did not affect the results and, further, instructions to participants were designed to mitigate the effects of expectations. Nonetheless, future studies should include a placebo condition, in order to confirm that the findings were not influenced by expectancies.

The study is further limited by the use of only one dose of amphetamine. It is possible that independent effects of the amphetamine response on quantitative measures of alcohol use might have been revealed if a higher dose of amphetamine had been used. In order to fully characterize the relationship between the amphetamine response and alcohol use, it will be important to evaluate multiple doses.

Finally, as with all studies that use retroactive self-report, the findings of the current study are subject to biases inherent in this methodology, such as intentional distortion, inaccuracies associated with recall, and misunderstanding of instructions (Del Boca and Darkes, 2003). The relationships observed here should be further evaluated using alcohol and drug use diaries, in laboratory-based self-administration studies, and, importantly, using a longitudinal design.

Summary and Significance

Sensitivity to the stimulant effects of alcohol is a candidate endophenotype for alcohol use disorders (Quinn and Fromme, 2011; Ray et al., 2010). The response to amphetamine has also been associated with various risk factors for alcoholism (Dlugos et al., 2011; Gabbay, 2005; Hutchison et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2006; 2009; Stanley et al., 2011; Stoops et al., 2003; 2007; White et al., 2006). The present study extends this work by demonstrating that, in combination with a strong amphetamine response, negative emotionality was associated with more alcohol use. In contrast, among individuals resilient to the stimulant effects of amphetamine, negative emotionality was unrelated to alcohol use. These findings are consistent with the idea that emotion-based dysregulation promotes behavior that leads to immediate reward and that, among individuals who are sensitive to the rewarding effects of drugs, dysregulation may promote risky alcohol use. Finally, the study also provided evidence of an effect of the amphetamine response on illicit drug use, which was independent of negative emotionality.

These findings encourage research to assess similarities in the responses to amphetamine and alcohol, as well as further exploration of neural mechanisms that mediate these commonalities. They also encourage additional study of co-variation between the amphetamine response and personality dimensions such as control, novelty-seeking, and impulsivity, and longitudinal studies to evaluate the interplay between drug response and these personality dimensions in the development of substance use. In particular, our results recommend studies that evaluate the effects of drug response and these personality traits on substance use when they occur in a context of negative affect.

Finally, the modulating effect of the stimulant response on the relationship between negative emotionality and risky alcohol use suggests that, for some individuals, pharmacotherapies designed to attenuate the reinforcing effects of drugs may be more effective when paired with interventions targeting deficits in emotion regulation.

Table 4b.

Linear Regression Statistics: Frequency of Binge Drinking in the Past Month (N = 160)

| Predictor | ΔR2 | p | Model F (df) | p | Standardized β | Bootstrapped p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. Gender | 0.066 | .001 | 11.082 (1, 158) | .001 | 0.262 | .009 |

| Step 2. Stim | 0.001 | .756 | 5.558 (2, 157) | .005 | −0.067 | .606 |

| Step 3. NEM | 0.006 | .332 | 4.020 (3, 156) | .009 | 0.081 | .285 |

| Step 4. Stim × NEM | 0.034 | .017 | 4.577 (4, 155) | .002 | 0.204 | .014 |

| Final R2 | 0.106 |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Table 4c.

Linear Regression Statistics: Frequency of Intoxication in the Past Year (N = 160)

| Predictor | ΔR2 | p | Model F (df) | p | Standardized β | Bootstrapped p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. Gender | 0.026 | .042 | 4.222 (1, 158) | .042 | 0.163 | .085 |

| Step 2. Stim | 0.002 | .541 | 2.290 (2, 157) | .105 | −0.029 | .809 |

| Step 3. NEM | 0.007 | .284 | 1.913 (3, 156) | .130 | 0.089 | .234 |

| Step 4. Stim × NEM | 0.024 | .049 | 2.451 (4, 155) | .048 | 0.172 | .014 |

| Final R2 | 0.059 |

Note. Stim = change score on the Stimulant scale of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (1.5 h – baseline); NEM = Negative Emotionality, higher-order factor scale on the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA018674) and the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-07-2-0046).

Footnotes

These exceptions reflected the rationale for the study. In previous research, a strong stimulant response has been associated with an enhanced response to reward more generally and with novelty-seeking and impulsivity. In turn, these traits have been found to co-occur with externalizing disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Thus, to minimize the exclusion of individuals with the trait of interest (i.e., an enhanced stimulant response), individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for these disorders were considered eligible for the study. However, only one participant out of 192 met the criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

References

- Agabio R, Carai MAM, Lobina C, Pani M, Reali R, Vacca G, Gessa GL, Colombo G. Alcohol stimulates motor activity in selectively bred Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP), but not in Sardinian alcohol-nonpreferring (sNP) rats. Alcohol. 2001;23:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Scher SJ. Self-defeating behavior patterns among normal individuals: review and analysis of common self-destructive tendencies. Psychol Bull. 1988;104:3–22. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, Peterson JL. Individual differences in rats’ reactivity to novelty and the unconditioned and conditioned locomotor effects of methamphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Dinwiddie SH, Begleiter H, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Porjesz B, Schuckit MA, Reich T. Familial transmission of substance dependence: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and habitual smoking: a report from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:982–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Hourani LL, Rae KL, Dever JA, Brown JM, Vincus AA, Pemberton MR, Marsden ME, Faulkner DL, Mandermaas-Peeler R. 2002 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Military Personnel. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle C, Assaad JM, Barrett SP, Avila C, Conrod PJ, Tremblay RE, Pihl RO. Heightened heart rate response to alcohol intoxication is associated with a reward-seeking personality profile. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:394–401. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117859.23567.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle C, Barrett SP, Pihl RO. Psychostimulant users are sensitive to the stimulant properties of alcohol as indexed by alcohol-induced cardiac reactivity. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:478–483. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, Treadway MT, Cowan RL, Woodward ND, Li R, Ansari MS, Baldwin RM, Schwartzman AN, Shelby ES, Smith CE, Kessler RM, Zald DH. Dopaminergic network differences in human impulsivity. Science. 2010;329:532. doi: 10.1126/science.1185778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TP. Affect regulation, nicotine addiction, and smoking cessation. J Psychoative Drugs. 1992;24:111–122. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson N, Harrington HL, Langlet J, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Personality differences predict health-risk behaviors in young adulthood: evidence from a longitudinal study. J Person Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1052–1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yücel M, Lubman DI. The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Fora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: the effects of familial alcoholism and personality. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MAD, de Wit H. Relationship between subjective effects and drug preferences: ethanol and diazepam. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34:243–251. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Petersen JB, Pihl RO. Disinhibited personality and sensitivity to alcohol reinforcement: independent correlates of drinking behavior in sons of alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1320–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Gearhardt A, Fromme K. Stimulant alcohol effects prime within session drinking behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquila PS, Peana AT, Tanda O, Serra G. Different sensitivity to the motor-stimulating effect of amphetamine in Sardinian alcohol-preferring and non-preferring rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;435:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre R, Farré M, Navarro M, Pacifici R, Zuccaro P, Pichini S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamine and related substances. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:157–185. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports for alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Individual differences in acute effects of drugs in humans: Their relevance to risk for abuse. In: Wetherington CL, Falk JL, editors. Laboratory Behavioral Studies of Vulnerability to Abuse (National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph No 169; NIH Publication No 98-4122) National Institutes of Health; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 176–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Uhlenhuth EH, Johanson CE. Individual differences in the reinforcing and subjective effects of amphetamine and diazepam. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1986;16:341–360. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(86)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Uhlenhuth EH, Pierri J, Johanson CE. Individual differences in behavioral and subjective responses to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11:52–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugos AM, Hamidovic A, Hodgkinson C, Shen PH, Goldman D, Palmer AA, de Wit H. OPRM1 gene variants modulate amphetamine-induced euphoria in humans. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Information Portal. [Accessed August 16, 2012]; Dextrostat (Dextroamphetamine Sulfate): Description and Clinical Pharmacology (December 9) 2011 Available at http://www.druglib.com/druginfo/dextrostat/description_pharmacology/

- Earleywine M. Confirming the factor structure of the anticipated biphasic alcohol effects scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:861–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, King SM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Personality traits and the development of nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drug disorders: prospective links from adolescence to young adulthood. J Ab Psychology. 2006;115:26–39. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erblich J, Earleywine M, Erblich B, Bovbjerg DH. Biphasic stimulant and sedative effects of ethanol: are children of alcoholics really different? Addict Behav. 2003;28:1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlke C, Hård E, Eriksson CJP, Engel JA, Hansen S. Amphetamine-induced hyperactivity: differences between rats with high or low preference for alcohol. Alcohol. 1995;12:363–367. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)00019-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Robinson TE, Clark JJ, Clinton SM, Watson SJ, Seeman P, Phillips PEM, Akil H. An animal model of genetic vulnerability to behavioral disinhibition and responsiveness to reward-related cues: Implications for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:388–400. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay FH. Variations in affect following amphetamine and placebo: markers of stimulant drug preference. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:91–101. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay FH. Family history of alcoholism and response to amphetamine: sex differences in the effect of risk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:773–780. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164380.16043.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galéra C, Bouvard MP, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Lagarde E, Michel G, Encrenaz G, Messiah A, Fombonne E. Disruptive symptoms in childhood and adolescence and early initiation of tobacco and cannabis use: the Gazel Youth study. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras MA, Cools AR. Analysis of the biphasic locomotor response to ethanol in high and low responders to novelty: a study in Nijmegen Wistar rats. Psychopharm. 1996;125:258–264. doi: 10.1007/BF02247337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson CD, Beckmann JS, Adams ZW, Marusich JA, Nesland TO, Yates JR, Kelly TH, Bardo MT. A translational behavioral model of mood-based impulsivity: Implications for substance abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;22:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;19:303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0022720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J, Oei TPS. Alcohol and tension reduction. In: Blaine T, Leonard K, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 2. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 14–53. [Google Scholar]

- Haertzen CA, Kocher TR, Miyasato K. Reinforcements from the first drug experience can predict later drug habits and/or addiction: results with coffee, cigarettes, alcohol, barbiturates, minor and major tranquilizers, stimulants, marijuana, hallucinogens, heroin, opiates and cocaine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1983;11:147–165. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(83)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Durbin CE, Blonigen DM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Relationship between personality change and the onset and course of alcohol dependence in young adulthood. Addiction. 2012;107:540–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock L, de Wit H. Individual differences in responses to ethanol and D-amphetamine: a within-subject study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:540–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock L, King AC, de Wit H. Subjective and objective responses to ethanol in moderate/heavy and light social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:789–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KE, Swift R. Effect of d-amphetamine on prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in humans. Psychopharmacology. 1999;4:394–400. doi: 10.1007/s002130050964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KE, Wood MD, Swift R. Personality factors moderate subjective and psychophysiological responses to d-amphetamine in humans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:493–501. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaak MI, Perkins DR, Labatut TR. Disregulated alcohol-related behavior among college drinkers: associations with protective behaviors, personality, and drinking motives. J Am College Health. 2011;59:282–288. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.509379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN. Personality research form manual. 3. Research Psychologists Press; Goshen, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Alcohol use disorders and psychological distress: a prospective state-trait analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:599–613. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LM, Taylor J. Impulsivity and negative emotionality associated with substance use problems and cluster B personality in college students. Addict Behav. 2007;32:714–727. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AJH, de Wit H. Acute effects of d-amphetamine during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Psychopharmacology. 1999;145:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s002130051033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Burkhart-Kasch S, McKinnon CS, Li N, Reed C, Philips TJ. Ethanol-related traits in mice selectively bred for differential sensitivity to methamphetamine-induced activation. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:1356–1366. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.6.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TH, Delzer TA, Martin CA, Harrington NG, Hays LR, Bardo M. Performance and subjective effects of diazepam and d-amphetamine in high and low sensation seekers. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:505–517. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283305e8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TH, Robbins G, Martin CA, Fillmore MT, Lane SD, Harrington NG, Rush CR. Individual differences in drug abuse vulnerability: d-amphetamine and sensation-seeking status. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0487-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, stimulant and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:389–399. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Houle T, de Wit H, Holdstock L, Schuster A. Biphasic alcohol response differs in heavy versus light drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:827–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. Personality traits in late adolescence predict mental disorders in early adulthood: a prospective-epidemiological study. J Personality. 1999;67:39–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Krull JL, Chassin L, Carle AC. The relation of personality to alcohol abuse/dependence in a high-risk sample. J Personality. 2000;68:1153–1175. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine MW, Swift RM. Development and validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Lynch KG, Pollock NK, Clark DB. Gender differences and similarities in the personality correlates of adolescent alcohol problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14:121–133. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Màsse LC, Tremblay RE. Behavior of boys in kindergarten and the onset of substance use during adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:62–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130068014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick RA, Dowd ET, Quirk S, Zegarra JH. The relationship of NEO-PI performance to coping styles, patterns of use, and triggers for use among substance abusers. Addict Behav. 1998;23:497–507. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: II. Alcoholism versus drug use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:394–404. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Taylor J, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: I. Effects of gender and alcoholism subtype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinzie DL, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of amphetamine on locomotor activity in adult and juvenile alcohol-preferring and nonpreferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00610-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measelle JR, Stice E, Springer DW. A prospective test of the negative affect model of substance abuse: moderating effects of social support. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:225–233. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, Goulet J, Preisig MA, Menton B, Zhang H, O’Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:973–979. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J. Moving the bar: transformations in linear regression. Paper presented at the meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association; Dallas TX. Jan 27-29.2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR. Subjective response to alcohol: a critical review of the literature. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morzorati SL, Ramchandani VA, Flury L, Li TK, O’Connor S. Self-reported subjective perception of intoxication reflects family history of alcoholism when breath alcohol levels are constant. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1299–1306. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000025886.41927.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Stewart RB, Bell RL, Badia-Elder NE, Carr LG, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of the Indiana University rat lines selectively bred for high and low alcohol preference. Behav Genet. 2002;32:363–388. doi: 10.1023/a:1020266306135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB, Renton RM. High risk groups often have higher levels of alcohol response than low risk: the other side of the coin. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:199–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB, Thompson JB. Alcohol challenge with sons of alcoholics: a critical review and analysis. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:383–402. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini C, Buchini F, Piazza PV, Puglisi-Allegra S, Cabib S. Susceptibility to amphetamine-induced place preference is predicted by locomotor response to novelty and amphetamine in the mouse. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172:264–270. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1647-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JB, Pihl RO, Gianoulakis C, Conrad P, Finn PR, Stewart SH, LeMarquand DG, Bruce KR. Ethanol-induced change in cardiac and endogenous opiate function and risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1542–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H. Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science. 1989;245:1511–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.2781295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher PJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Ed Behav Stat. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Subjective response to alcohol challenge: a quantitative review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1759–1770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]