Abstract

Miswak (Salvadora persica Linn.) is a medium-sized tree, desert facultative halophytic plant. Besides edible fruits and non-edible seed oil, the plant contains several bioactive compounds like alkaloids, tannins, saponins and sterols related to food and cosmetic industries. In the present study, physiological responses and antioxidant potential under salinity stress were investigated in callus cultures of S. persica to evaluate its use as a source of antioxidant. The callus cultures were grown on MS medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/l each of 2,4,5-T and BAP, which could be established successfully by regular subcultures of slow growing callus on this medium for several months. Increased dry weight, soluble proteins, proline, soluble carbohydrates and CAT activity were recorded under NaCl stress in comparison to control cultures. The DPPH and FRAP antioxidant activities were gradually elevated in NaCl-treated callus, whereas SOD quenching was recorded maximum at 200 mM. A significant correlation between antioxidant capacity and phenol content was observed, indicating that phenolic compounds are the major contributors to the antioxidant potential in S. persica. These findings suggest that increased salinity stress caused elevated antioxidant potentials and the plants grown in such conditions may serve as potential source of antioxidant.

Keywords: Antioxidant, Catalase, Salinity, Salvadora persica, Phenolics, Proline

Introduction

High salinity, drought, extreme light and temperature are the most serious environmental stresses impending plant growth and limiting crop productivity worldwide (Munns 2005). In salt affected plants, the result is primarily an ionic imbalance and hyper osmotic stress (Tester and Davenport 2003). The effect of this imbalance or disruption in homeostasis occurs at the cell as well as the whole plant levels. Finally, in extreme saline condition, molecular damage and growth arrest lead to death of plant (Jitesh et al. 2006). Salt-tolerant plants have evolved a variety of physiological responses that confer capacity for osmotic adjustment. These plants accumulate osmolytes such as glycine, betaine and proline that maintain the osmotic balance disrupted by the presence of ions in the vacuole (Wang et al. 2004). Investigations of halophytes indicated that significantly increased levels of proline and soluble carbohydrates are probably related to osmotic adjustment and the protection of membrane stability under salinity stresses (Megdiche et al. 2007). Proteins that accumulate in plants under saline conditions may provide a storage form of nitrogen that is re-utilized later and also play a role in osmotic adjustment.

In accordance with the established mechanism of ROS generation, oxidative stress has been reported in several plant species after NaCl stress treatment. Further, plant materials containing phenolic compounds are increasingly of interest for the food industry as they participate in the defense against ROS. Thus, drought-stressed plants might represent potential sources of polyphenols for economical use (Bettaieb et al. 2011). The correlation between antioxidant capacity and salt tolerance was demonstrated in a large number of plants, including salt-tolerant glycophytes and true halophytes such as Beta maritime, Cassia angustifolia and Crithmum maritimum (Li 2008).

Salvadora persica Linn. (Family Salvadoraceae) is a typical facultative halophytic plant, grows in arid regions from western India to Middle East as well as high saline lands along the sea coasts. It is an important plant of arid horticulture (edible fruits and non-edible seed oil) and forestry, hence micropropagation method has been developed (Phulwaria et al. 2011). The WHO recommends and encourages the use of chewing sticks of miswak as an effective oral hygiene procedure in areas where its use is traditional WHO (1987). The plant shows several biological activities (antimicrobial, dental plaque and gingivitis, anti-inflammatory and analgesic) due to major bioactive compounds like alkaloids, tannins, saponins and sterols (Ahmad et al. 2011; Akhtar et al. 2011; Sofrata et al. 2011a, b). In harsh saline and hot desert conditions, these plants support wild life and are integral part of ecosystem. Details of biology, physiology and usage have been reviewed (Kasera and Mohammed 2010; Khan et al. 2006; Sen et al. 2002).

Cell and tissue culture offers monitoring plant responses to salinity at biochemical and physiological levels (Yang et al. 2010; Matkowaski 2008). In the present study, S. persica callus cultures have been used for the first time to investigate salt stress adaptive mechanism, and correlate with antioxidant activity under salt stress for its possible use as a source of antioxidant in salty desert conditions.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The explants were obtained from 20- to 30-year-old mature tree of S. persica growing near to the University campus. The explants were washed under running tap water for 20 min to remove any adherent particles. Thoroughly washed explants were then immersed in 1 % (v/v) Teepol, a liquid detergent for 2–3 min, and thereafter surface sterilized in ethanol for 30 s. The explants were immersed in 0.1 % (w/v) aqueous solution of HgCl2 for 10 min, rinsed with distilled water and then suitable size nodal explants (~1 cm) were inoculated on to the medium. Murashige and Skoog (1962) (MS) medium contained 3 % sucrose, 0.8 % agar with different combinations and concentrations of plant growth regulators. The pH was adjusted to 5.8 and autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. Organic supplements like coconut milk (10 %) and all vitamins (twofold) were used for the improvement of callus growth and friability. The callus was then separated from the initial explants and subcultured every 30–35 days. The callus was maintained on MS medium with combinations of 2,4,5-T and BAP, 0.5 mg/l each, 3 % (w/v) sucrose, double vitamins and 0.8 % (w/v) agar.

For salt stress experiment, different NaCl concentrations (0, 50, 100 and 200 mM) were added in MS medium and 40 ml medium was poured in 100-ml wide-mouth conical flasks. The callus (2.0 g) was inoculated in each flask and these cultures were incubated at 25 ± 0.2 °C under a 16 h d−1 photoperiod with 50 μmol m−2 s−1 irradiance. Fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) were determined after 30-day growth.

Soluble protein analysis

The samples were collected from untreated and 30-day NaCl-treated callus for estimation of soluble proteins. The callus (250 mg) was ground in chilled tris-(hydroxymethyl) amino methane (Tris)–HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 6.8), then centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 min. The supernatants obtained were used for protein assay according to the method of Bradford (1976) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Proline and soluble carbohydrate assay

The amount of proline was estimated by the ninhydrin method using fresh callus (0.5 g) in 3 % sulfosalicylic acid and organic phase monitored at 520 nm by spectrophotometer (Specord 200, Analyte Jena, Germany) (Bates et al. 1973). A modification of the method of phenol–sulfuric acid was used to determine soluble sugar content at 490 nm (Dubois et al. 1956).

Catalase activity measurement

Catalase activity was measured by the method of Aebi (1974). The assay system comprised 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 20 mM H2O2, and a suitable aliquot of enzyme in the final volume of 3 ml. The change of absorption values was recorded at 240 nm for 3 min. CAT activity was estimated by calculating the initial rate of disappearance of H2O2.

Determination of antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity was determined by extraction of samples, which were pooled and analyzed in triplicates. Dried powdered callus sample (200 mg) was extracted 12 h at room temperature by shaking on a test tube rotator with 5 ml of 70 % methanol. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 10 °C and supernatant was used for antioxidant activities.

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity was determined according to the method described by Hatano et al. (1988). The reaction mixture (total volume 3 ml), consisting of 0.5 ml of 0.5 M acetic acid buffer solution at pH 5.5, 1 ml of 0.2 mM DPPH in ethanol, and 1.5 ml of 50 % (v/v) ethanol aqueous solution, was shaken vigorously with various samples. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the remaining DPPH was determined by absorbance at 517 nm, and the radical scavenging activity of each sample was expressed using the ratio of the absorption decrease of DPPH (%) to that of the control DPPH solution (100 %) in the absence of the sample. The radical scavenging activity was calculated as (%) = 100(A − B)/A, where A and B are the 517 nm absorption of the control and the corrected absorption of the sample reaction mixture.

Superoxide radical scavenging activity (PMS/NADH system)

Superoxide anions were generated using PMS/NADH system. The superoxide anions are subsequently made to reduce nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) which yields a chromogenic product, which is measured at 560 nm. The absorbance was read at 560 nm (Jain et al. 2008) and the inhibition percentage of superoxide anion generation was calculated the same as DPPH activity formula.

Ferric reducing antioxidant potential (FRAP) assay

The ferric reducing power of plant extracts was determined using the method of Benzie and Strain (1996). The reaction mixture, containing 100 μl of sample solutions, 300 μL of deionized water and 3 ml of FRAP reagent, was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a water bath and read at 593 nm. The difference between sample absorbance and blank absorbance was calculated and used to calculate the FRAP value. FRAP values were expressed as mmol Fe2+/g of sample.

Determination of total phenolic content

Phenolic compounds were assayed using the Foline–Ciocalteu reagent, by following the method of Farkas and Kiraly (1962). TPC was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) g−1 DW through the calibration curve with gallic acid at 650 nm.

Statistical analysis

All results were averaged over three separate analyses from six flasks of each treatment and experiment was done in duplicate. Results were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by ANOVA followed by post hoc least significant difference (LSD) test at P ≤ 0.05 using prism statistical software. To correlate the results obtained with different methods, a regression analysis was performed and correlation coefficients were calculated.

Results and discussion

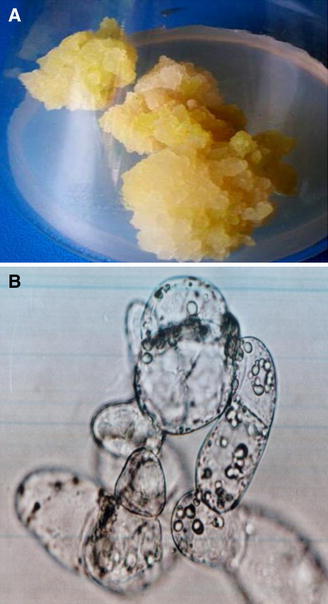

The results obtained with callus tissues of S. persica grown under NaCl-generated salinity stress showed increased salt tolerance in cells as evident by higher dry weight, metabolic and antioxidant activities. Being a slow growing desert plant, initial growth of the callus produced from mature explants was very slow on different permutations and combinations of MS medium salts, plant growth regulators and complex addendum. However, soft, friable and cream colored cultures could be established after several subcultures on the medium containing a combination of 2,4,5-T and BAP (0.5 mg/l each), 3 % (w/v) sucrose, double vitamins and 0.8 % (w/v) agar. On this medium, metabolically active cells were visible under microscope (Fig. 1a, b). Salt stress creates both ionic as well as osmotic stress on plants.

Fig. 1.

a Callus and b cells of Salvadora persica

Effect of NaCl on growth and soluble protein contents

Reduced fresh weight with higher or same dry weight and protein contents were observed in the callus after 30-day growth on the medium with NaCl (Table 1). Loss of water with high salt concentration but increased dry matter and soluble protein showed high metabolic activity.

Table 1.

Effect of NaCl on the growth and soluble proteins of callus culture of Salvadora persica

| Growth | NaCl concentrations (mM)*# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 50 | 100 | 200 | |

| Relative fresh weight (%) | 100 ± 1.20a | 91.66 ± 1.05b | 83.33 ± 1.15c | 66.66 ± 1.54d |

| Dry weight (mg) | 510 ± 18.0bc | 580 ± 15.5a | 540 ± 20.3b | 500 ± 12.6c |

| Soluble protein (mg g−1 FW) | 1.0 ± 0.06c | 1.9 ± 0.10a | 1.8 ± 0.07a | 1.6 ± 0.13b |

* Values represented mean ± SD calculated from at least three replicates of each treatment

#Mean with common letter is not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to least significant difference (LSD) test

Fresh weight and dry weight are often measured to reveal the growth of plants and cells in response to environmental stresses. In the present study, salt concentrations induced significant elevation in dry weight in S. persica callus, which suggest a cellular tolerance to lower salinity in this halophytic species. Similar results of growth were found in Nitraria tangutorum and Oryza sativa callus (Yang et al. 2010). The expression of proteins is regulated in plants depending on salt concentration (Sekmen et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2010). Proteins that accumulate in plants under saline conditions are cytoplasmic, which can cause alterations in cytoplasmic viscosity of the cells and may play a significant role in osmotic adjustment (Hasegawa et al. 2000). Similar results were also obtained in mulberry cultivars where soluble protein increased at low salinity and decreased at high salinity (Agastian et al. 2000).

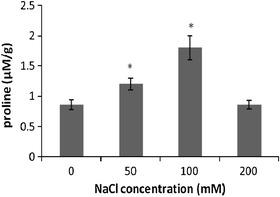

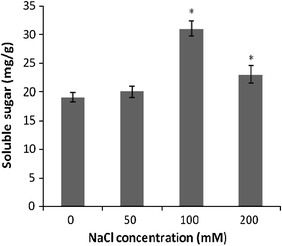

Effect of NaCl stress on proline and soluble sugar contents

Proline level in response to NaCl treatment (Fig. 2) showed an approximately 1.30- and 2.09-fold increase in the content in the callus exposed to 50 and 100 mM NaCl, respectively (P < 0.05), as compared with control cultures. However, treatment with 200 mM NaCl led to a decrease in proline content which was equivalent to that of control value. In callus cultures of S. persica, soluble sugar content increased significantly from 1.0- to 1.6-fold under salinity stress (P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Therefore, it appears that proline possibly plays a more important role as an osmoprotectant in S. persica callus subjected to salinity stress than to soluble sugar.

Fig. 2.

The change of proline contents induced by NaCl treatment in the callus of S. persica. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). *Significant differences between the control and treated callus (P < 0.05)

Fig. 3.

The change of soluble sugar contents induced by NaCl treatment in the callus of Salvadora persica. Data represent the means ± SE of at least three independent measurements. *Significant differences between the control and treated callus (P < 0.05)

Proline is known to play an important role as an osmoprotectant and is accumulated when plants are subjected to hyperosmotic stresses (Suriyan and Chalermpol 2009). Maintaining osmotic homeostasis by accumulating metabolically compatible compounds such as carbohydrates and proline may be among the important adaptive mechanisms of salinity tolerance in plants (Rosa et al. 2009). Increased proline and sugar contents were correlative with increased salinity stress in the callus of S. persica. In Sesuvium portulacastrum, treatment with 100 mM NaCl induced significantly increased levels of proline in the leaves, but it had no effect on soluble sugar content (Slama et al. 2007). Proline is also considered to be involved in the protection of enzymes, cellular structures, and to act as a free radical scavenger (Aghaleh et al. 2011).

Effect of NaCl on CAT activity

An increase in 82, 122 and 113 % CAT activity was measured in the callus grown on 50, 100 and 200 mM NaCl containing medium for 30 days, respectively, (P < 0.05), as compared to control culture values (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The changes in CAT activity in S. persica callus treated with different NaCl concentrations. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). *Significant differences between the control and NaCl treated callus (P < 0.05)

An effective ROS-scavenging system involving catalase is a critical component of salinity resistance because of its protective effect against oxidative damage under salinity stress. Catalase is one of the main H2O2 scavenging enzymes that dismutate H2O2 into water and O2 (Moradi and Ismail 2007; Li 2008). When Bruguiera parviflora plants were subjected to 400 mM NaCl stress condition, a decrease in total catalase activity was observed by Jitesh et al. (2006), while increased CAT activity was demonstrated in Nitraria tangutorum callus culture after 50 or 100 mM NaCl treatment (Yang et al. 2010). Thus, catalase enzyme activity varied with different plant species and with salt stress.

Effect of NaCl stress on antioxidant potential and total phenolic content

Antioxidant capacity was evaluated by DPPH and SOD anion activities. DPPH radical scavenging activity of callus cultures of S. persica increased gradually from 1.26- to 1.78-fold when grown on increasing concentrations of NaCl for 30 days (Table 2). FRAP and SOD activities of S. persica callus cultures were also increased steadily from 9 to 12 % and 11 to 17 mM Fe2+ g−1 under 50 to 200 mM NaCl treatments, respectively (Table 2). Increased protein and metabolites were correlative to increased TPC, DPPH, SOD and FRAP in the cells grown with increased salt stress as compared to control. The plant cells showed increase in all parameters under increased stress indicating a salt-induced response for survival in harsh temperature and salt conditions with increase of dry matter accumulation. Simultaneously, TPC of the callus cultures under salinity stress increased from 11 to 12 mg GAE g−1 in the cultures grown on the medium with increased concentration of NaCl as compared to control cultures (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of NaCl on the total phenolic content (TPC) and radical scavenging capacity of callus culture of Salvadora persica

| TPC and antioxidant activity | NaCl concentrations (mM)*# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 50 | 100 | 200 | |

| TPC (mg GAE g−1) | 10 ± 0.45b | 11 ± 0.70a | 11 ± 0.34a | 12 ± 0.86a |

| DPPH scavenging activity (%) | 46 ± 2.3d | 58 ± 3.0c | 65 ± 3.4b | 82 ± 4.1a |

| SOD quenching (%) | 6 ± 0.37c | 9 ± 0.45b | 10 ± 0.40b | 12 ± 0.92a |

| FRAP activity (mM Fe2+ g−1) | 8 ± 0.66d | 11 ± 0.40c | 13 ± 0.55b | 17 ± 1.03a |

* Values represented mean ± SD calculated from at least three replicates of each treatment

#Mean with common letter is not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to least significant difference (LSD) test

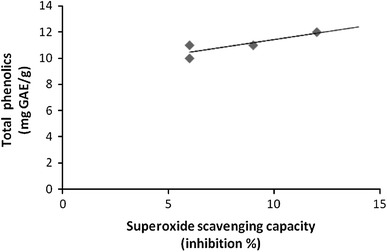

Correlation between assays

In order to correlate the results obtained with the different methods, a regression analysis was performed (correlation coefficient R, Table 3). Significant correlations were established between FRAP and TPC (R = 0.973, Fig. 5), and SOD and TPC (R = 0.852, Fig. 6) assay. A significant correlation (R = 0.760, Fig. 7) was also observed between FRAP and SOD assay. However, the negative correlations were found between FRAP and DPPH (R = −0.164), SOD and DPPH (R = −0.532) and TPC and DPPH (R = −0.153) assays. The negative correlation coefficient of above assays shows that as the value of one variable increases, the value of other variable decreases, and vice versa. The DPPH activity commonly showed negative correlation with FRAP, SOD and TPC.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficient (R) between assays

| FRAP | SOD | DPPH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOD | 0.760 | ||

| DPPH | −0.164 | −0.532 | |

| TPC | 0.973 | 0.852 | −0.153 |

Fig. 5.

Correlation between ferric reducing capacity (FRAP) and total phenolic content (TPC). Correlation coefficient R = 0.973

Fig. 6.

Correlation between superoxide scavenging capacity (SOD) and total phenolic content (TPC). Correlation coefficient R = 0.852

Fig. 7.

Correlation between superoxide scavenging capacity (SOD) and ferric reducing capacity (FRAP). Correlation coefficient R = 0.760

Salt-induced growth variations were correlated with parallel variations in polyphenols accumulation and antioxidative ability. NaCl-treated callus of S. persica demonstrated that DPPH radical scavenging activity, FRAP activity and SOD activity increased significantly. Similarly, Lechno et al. (1997) reported that NaCl treatment increases the activities of the antioxidative enzymes. These activities may be directly linked to the content of phenols, tannins and flavonoids and consequently to their free radical scavenging activities. Besides, plant resistance to various stresses is associated with antioxidant capacity and increased levels of antioxidants may prevent stress damage (Bettaieb et al. 2011).

These results indicate a significant correlation between TPC in callus extract and their free radical scavenging and ferric reducing capacities (FRAP and SOD assays). Therefore, the presence of phenolic compounds in callus extracts contributed significantly to their antioxidant potential. In our experiments, results demonstrated a strong correlation between TPC and FRAP activity. Similarly, previous studies suggested that ferric reducing capacity can be related to phenolic content, indicating that phenolic compounds are the major contributor to the antioxidant potential of different plant extracts (Dudonne et al. 2009).

In conclusion, our results showed that salinity-induced in vitro cultures are better model system for the study of stress mechanism, which is independent from environmental factors. The callus cultures of S. persica showed moderate salt-tolerant properties and can be used as source of antioxidants in harsh saline desert conditions for humans (fruits) and cattle (leaves).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by financial assistance from University Grants Commission-Departmental Research Programme (UGC-DRS) under special assistance program for medicinal plant research to K.G. Ramawat. V. Sharma thanks to UGC New Delhi, for financial assistance in the form of SRF.

Abbreviations

- BAP

6-Benzyl aminopurine

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- CAT

Catalase

- 2,4,5-T

2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxy acetic acid

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- DPPH

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl

- FRAP

Ferric reducing antioxidant potential

- TPC

Total phenolic content

References

- Aebi H. Catalase. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. In methods of enzymatic analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 673–677. [Google Scholar]

- Agastian P, Kingsley SJ, Vivekanandan M. Effect of salinity on photosynthesis and biochemical characteristics in mulberry genotypes. Photosynthetica. 2000;38:287–290. doi: 10.1023/A:1007266932623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aghaleh M, Niknam V, Ebrahimzadeh H, Razavi K. Effect of salt stress on physiological and antioxidative responses in two species of Salicornia (S.Persica and S. europaea) Acta Physiol Plant. 2011;33:1261–1270. doi: 10.1007/s11738-010-0656-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Imran H, Yaqeen Z, Rehman Z, Rahman A, Fatima N, Sohail T. Pharmacological profile of Salvadora persica. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2011;24:323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar J, Siddique KM, Bi S, Mujeeb M. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological investigations of miswak (Salvadora persica Linn) J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:113–117. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates CJ, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettaieb I, Sellami IH, Bourgou S, Limam F, Marzouk B. Drought effects on polyphenol composition and antioxidant activities in aerial parts of Salvia officinalis L. Acta Physiol Plant. 2011;33:1103–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11738-010-0638-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;38:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dudonne S, Vitrac X, Coutiere P, Woillez M, Merillon JM. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:1768–1774. doi: 10.1021/jf803011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas GL, Kiraly Z. Role of phenolic compound in the physiology of plant diseases and disease resistance. Phytopathologische Zeitschrift. 1962;44:105–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1962.tb02005.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa PM, Bressan RA, Zhu JK, Bohnert HJ. Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:463–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Kagawa H, Yasuhara T, Okuda T. Two new flavonoids and other constituents in licorice root: their relative astringency and radical scavenging effects. Chem Pharm Bull. 1988;36:2090–2097. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain PK, Ravichandran V, Agrawal RK. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties of traditionally used three Indian medicinal plants. Curr Trends Biotech Pharm. 2008;2:538–547. [Google Scholar]

- Jitesh MN, Prashanth SR, Sivaprakash KR, Parida AK. Antioxidative response mechanism in halophytes: their role in stress defence. J Genet. 2006;85:237–253. doi: 10.1007/BF02935340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasera PK, Mohammed S. Ecology of saline plants. In: Ramawat KG, editor. Desert plants biology and biotechnology. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Ansari R, Gul B, Qadir M (2006) Crop diversification through halophyte production on salt prone land resources. CAB Rev Perspectives Agric Vet Sci Nutr Nat Resour 1:048. doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR20061048

- Lechno S, Zamski E, Telor E. Salt stress-induced responses in cucumber plants. J Plant Physiol. 1997;150:206–211. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(97)80204-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Kinetics of the antioxidant response to salinity in the halophyte Limonium bicolor. Plant Soil Environ. 2008;54:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Matkowaski A. Plant in vitro culture for the production of antioxidants—a review. Biotech Adv. 2008;26:548–560. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megdiche W, Amor NDA, Hessini K, Ksouri R, Zuily-Fodil Y, Abdelly C. Salt tolerance of the annual halophyte Cakile maritima as affected by the provenance and the developmental stage. Acta Physiol Plant. 2007;29:375–384. doi: 10.1007/s11738-007-0047-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi F, Ismail AM. Responses of photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and ROS-scavenging systems to salt stress during seedling and reproductive stages in rice. Ann Bot. 2007;99:1161–1173. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. Genes and salt tolerance bringing them together. New Phytol. 2005;167:645–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phulwaria M, Ram K, Gahlot P, Shekhawat NS. Micropropagation of Salvadora persica—a tree of arid horticulture and forestry. New Forest. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Rosa M, Hilal M, Gonza′lez JA, Prado FE, et al. Low-temperature effect on enzyme activities involved in sucrose–starch partitioning in salt-stressed and salt-acclimated cotyledons of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekmen AH, Turkan I, Takio S. Differential responses of antioxidative enzymes and lipid peroxidation to salt stress in salt-tolerant Plantago maritima and salt-sensitive Plantago media. Physiol Plant. 2007;131:399–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen DN, Mohammed S, Kasera PK. Biology and physiology of saline plants. In: Pessarakli M, editor. Handbook of plant and crop physiology. 2. New York: Dekker; 2002. pp. 563–581. [Google Scholar]

- Slama I, Ghnaya T, Messedi D, Hessini K, Labidi N, Savoure A, Abdelly C. Effect of sodium chloride on the response of the halophyte species Sesuvium portulacastrum grown in mannitol-induced water stress. J Plant Res. 2007;120:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s10265-006-0056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofrata A, Brito F, Al-Otaibi M, Gustafsson A. Short term clinical effect of active and inactive Salvadora persica miswak on dental plaque and gingivitis. J Ethanopharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofrata A, Santangelo EM, Azeem M, Borg-Karlson AK, Gustafsson A, Pütsep K. Benzyl isothiocyanate, a major component from the roots of Salvadora persica is highly active against gram-negative bacteria. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suriyan C, Chalermpol K. Proline accumulation, photosynthetic abilities and growth characters of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) plantlets in response to iso-osmotic salt and water-deficit stress. Agric Sci China. 2009;8:51–58. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60008-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tester M, Davenport R. Na+ tolerance and Na+ transport in higher plants. Ann Bot. 2003;91:503–527. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Luttge U, Ratajczak R. Specific regulation of SOD isoforms by NaCl and osmotic stress in leaves of the C3 halophytes Suaeda salsa L. J Plant Physiol. 2004;161:285–293. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1987) Prevention of oral diseases. WHO, Geneva

- Yang Y, Wei X, Shi R, Fan Q, An L. Salinity-induced physiological modification in the callus from halophytes Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. J Plant Growth Regul. 2010;29:465–476. doi: 10.1007/s00344-010-9158-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]