Abstract

We investigated whether healthy young (age ≤ 40) and elderly (age ≥ 65) people infected with cytomegalovirus (CMV) had similar levels of CD8+ T cell cytokine production and proliferation in response to an immunodominant CMV pp65 peptide pool given the role of CD8+ T cells in controlling viral infection and the association of CMV with immunosenescence. Plus, we determined the effects of aging and CMV-infectious status on plasma levels of IL-27, an innate immune cytokine with pro- and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as on its relationship to IFN-γ in that IL-27 can promote the production of IFN-γ. The results of our study show that young and elderly people had similar levels of CD8+ T cell proliferation, and IFN-γ and TNF-α production in response to CMV pp65 peptides. Plasma levels of IL-27 were similar between the two groups although CMV-infected young and elderly people had a trend toward increased levels of IL-27. Regardless of aging and CMV-infectious status, plasma levels of IL-27 correlated highly with plasma levels of IFN-γ. These findings suggest the maintenance of CMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation and cytokine production with aging as well as the sustaining of circulatory IL-27 levels and its biological link to IFN-γ in young and elderly people irrespective of CMV infection.

Keywords: CD8+ T cells, IL-27, Human, aging, cytomegalovirus (CMV)

1. Introduction

CD8+ T cells are critically involved in host defense against viral infections [1]. These cells can directly kill virus-infected cells. Also, cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α produced from CD8+ T cells participate in controlling viral infections. In particular, IFN-γ can stimulate monocytes and macrophages to produce cytokines and chemokines as well as promote MHC class I molecule expression on virus-infected target cells [2]. In mice infected with viruses, the deficiency of IFN-γ production from T cells was associated with delayed viral clearance [3]. In addition, inhibition of hepatitis B viral gene expression was abrogated in mice that were neutralized of IFN-γ and TNF-α [4].

Alterations in T cell immunity occur with aging. These changes include involution of the thymus, the organ where T cells mature, with a decreased generation of naïve T cells [5]. In addition, expansion of memory CD8+ T cells with reduced T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire is found in humans with aging [5–7]. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), which establishes persistent infection, has been suggested as a potential driving force for the age-associated expansion of memory CD8+ T cells based on the observations showing the increased frequency of CMV-specific cells in the expanded memory CD8+ T cells [8–10]. CD8+ T cells, a major cellular source of IFN-γ, are critically involved in defending the host against viral infection and reactivation [1]. These findings suggest a possible change in cytokine production and proliferation of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells in humans with aging, leading to the altered proportion of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. However, it is still controversial whether CMV-specific CD8+ T cells have altered function in the elderly [11–14].

The cytokine IL-27 is composed of the p27 and Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene (EBI3) subunits (reviewed in [15, 16]). The p27 and EBI3 subunits are produced primarily by dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages. The receptor complex for IL-27 comprises WSX-1 (IL-27 receptor alpha) and gp130, which is also shared by other cytokines including IL-6 and IL-11 receptors. IL-27 appears to have both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects [15, 16]. IL-27 is known to promote IFN-γ-producing T helper 1 (Th1) cell response [17]. Similarly, enhanced IFN-γ production from human naïve CD8+ T cells by IL-27 was reported [18]. Recent work showed that IL-27 could increase the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 by a subset of CD4+ T cells in mice and humans [19–21], suggesting an immune regulatory function of this cytokine. Also, IL-27 suppressed the development of experimental allergic encephalitis (EAE) and collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), mouse models of multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively [19, 22, 23]. Viruses including influenza A and hepatitis B viruses induced the production of IL-27 [24, 25]. In fact, patients infected with hepatitis B virus had increased levels of IL-27 in blood compared to healthy controls [25]. These data indicate the involvement of viral infection in producing IL-27 with pro- and anti-inflammatory properties. However, little is known about the effect of aging and CMV-infectious status on blood IL-27 levels and the relationship of such cytokine levels to IFN-γ levels in humans.

In this study, we investigated the effects of aging on cytokine production and proliferation of CD8+ T cells in response to the CMV immunodominant protein pp65 in healthy people. We also determined whether CMV-infectious status and aging affected circulatory levels of IL-27 and its relationship to IFN-γ levels. Healthy young (age ≤ 40) and elderly (age ≥ 65) people had similar frequencies of CD8+ T cells that proliferated and produced IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to CMV pp65 protein in peripheral blood. In addition, young and elderly people had similar levels of plasma IL-27 although the ones infected with CMV had a trend towards increased levels of plasma IL-27 compared to the ones uninfected with this virus. Of interest, IL-27 levels correlated with plasma IFN-γ levels in young and elderly people regardless of CMV-infectious status, which supports the biological link of the two cytokines. These findings indicate that CMV-specific CD8+ T cell responses, as measured by cytokine production and cell proliferation, are preserved with aging and that circulatory levels of IL-27 and its relationship to IFN-γ is maintained in the elderly regardless of CMV infectious status.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human subjects and cells

Healthy young (age ≤ 40, n = 85) and elderly (age ≥ 65, n = 59) subjects were recruited for this study (mean age ± SD, 28.8 ± 5.2 and 73.9 ± 5.8). There was no gender difference between the two groups (males to females, 23:62, 16:43 for young and elderly groups, respectively, P = 0.994 by Chi-square test). Six of the recruited subjects were smokers. Individuals who were taking immunosuppressive drugs or who had any disease potentially affecting the immune system including autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, malignancy, diabetes and asthma were excluded [26–29]. This study was approved by the institutional review committee of Yale University. Peripheral blood was drawn after informed consent. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from blood on FicollPAQUE gradients. The CMV infection status (IgG) was determined by ELISA (Bio-Quant Diagnostic Kits, San Diego, CA).

2.2. Analyses for cytokine production and cell proliferation

To measure cytokine production by CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, PBMCs from CMV-positive individuals were stimulated for 6 hours with or without a CMV pp65 peptide pool (ProMix™ HCMVA (PP65), Proimmune, Sarasota, FL) in the presence of Golgi plug (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) during the last 5 hours of stimulation. Stimulated cells were fixed and permeabilized using appropriate buffers (Cytofix/Cytoperm buffers, BD Pharmingen) followed by staining with antibodies to APC-Cy7-CD3, Pacific Blue-CD8, APC-IFN-γ and FITC-TNF-α or isotype controls (BD Pharmingen). Stained cells were analyzed on an LSRII® flow cytometer. For determination of CD8+ T cell proliferation in response to CMV pp65 peptides, PBMCs were stained with carboxyfluorescein diacetate (CFSE, Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR) and stimulated for 7 days with or without the CMV pp65 peptide pool (Proimmune). Cells were then analyzed on an LSRII® flow cytometer. The frequency of CMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cells which proliferated or produced IFN-γ or TNF-α was obtained by subtracting the frequency of proliferating or cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells in unstimulated samples from the frequency of the same cells in samples stimulated with CMV pp65 peptides.

2.3 Measuring plasma IL-27 and IFN-γ

IL-27 and IFN-γ levels in plasmas were measured by commercially available ELISA kits (BioLegend, San Diego, CA and ebioscience, San Diego, CA, respectively) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The unpaired Student’s t-test, Pearson and Spearman correlations were done for statistical analyses as appropriate using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL). P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Young and elderly people have similar frequencies of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood in response to CMV pp65 protein

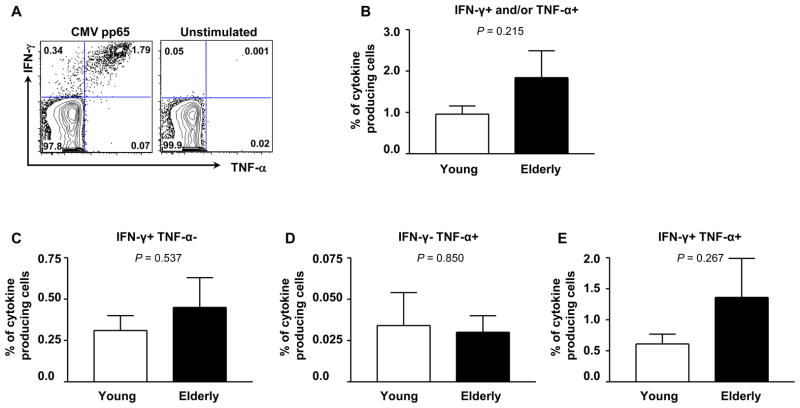

We measured the frequency of IFN-γ- and/or TNF-α-producing CD8+ T cells in young and elderly people using flow cytometry after stimulating PBMCs with an immunodominant CMV pp65 peptide pool (Figure 1A, representative figure). A large number of CD8+ T cells producing these cytokines could produce both IFN-γ and TNF-α at the single cell level in response to CMV pp65 peptide pool. In both groups, the frequency of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and/or TNF-α was typically less than 2% of total CD8+ T cells and was not different between young and elderly people people (mean frequency (%) ± standard error of mean (SEM), 0.96% ± 0.20 vs. 1.84% ± 0.65) (Figure 1B). Young and elderly people had similar frequencies of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ or TNF-α alone (Figure 1C–D). Similarly, the frequency of CD8+ T cells producing both cytokines was not different between the two groups (Figure 1E). These findings suggest that the frequency of CMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cells that produce IFN-γ and TNF-α is sustained in humans with aging.

Figure 1. Young and elderly people have similar frequencies of CD8+ T cells that produce IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to CMV pp65 peptides.

PBMCs were purified from the peripheral blood of young (age ≤ 40) and elderly (age ≥ 65) donors infected with CMV and stimulated for 6 hours with or without a CMV pp65 peptide pool in the presence of Golgi plug during the last 5 hours of stimulation. Stimulated cells were fixed and permeabilized using appropriate buffers followed by staining with antibodies to CD3, CD8, IFN-γ and TNF-α (BD Pharmingen). Stained cells were analyzed on an LSRII® flow cytometer. (A) Representative data showing CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and/or TNF-α in response to CMV pp65 peptides. (B–E) The frequency of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and/or TNF-α (B), IFN-γ only (C), TNF-α only (D) and both IFN-γ and TNF-α (E) in response to CMV pp65 peptides in young (n = 12) and elderly people (n = 14). Bars and error bars indicate mean and standard error of mean (SEM), respectively.

3.2. Young and elderly people have similar levels of CD8+ T cell proliferation in response to CMV pp65 peptides

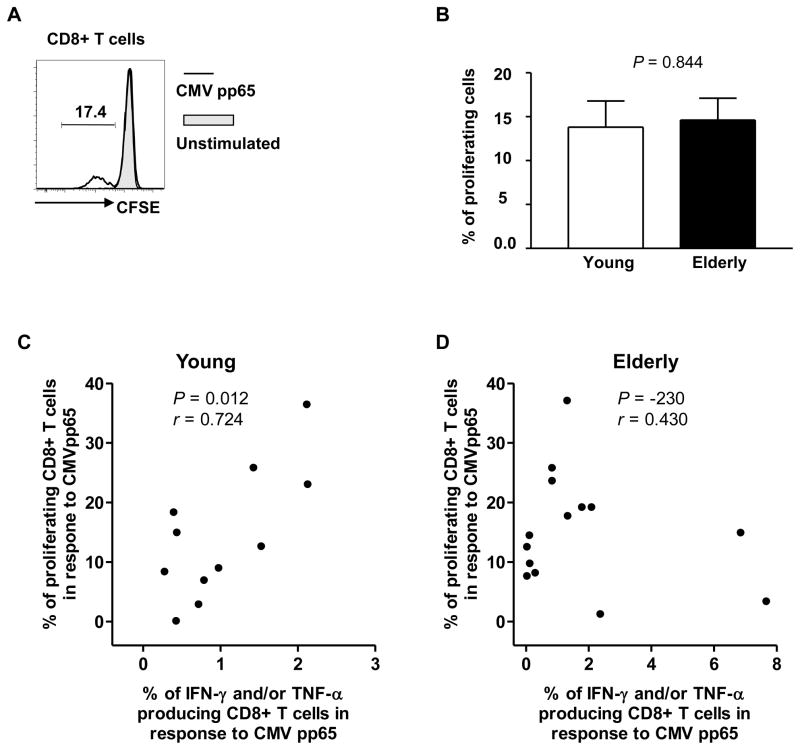

We measured the proliferation of CD8+ T cells in response to the CMV pp65 peptides in CD8+ T cells in young and elderly people (Figure 2A, representative figure). The frequency of proliferating cells was not different between the two groups (mean frequency (%) ± SEM, 13.8% ± 3.02 vs. 14.6% ± 2.47) (Figure 2B). The frequency of CMV pp65-specific proliferating cells correlated with the frequency of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and/or TNF-α in response to the CMV pp65 peptides in the young (r = 0.724, P = 0.012) (Figure 2C). However, such correlation was not found in the elderly (Figure 2D). These observations suggest that an age-associated alteration may occur in the relationship between the capacities of cytokine production and cell proliferation in CMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cells in humans.

Figure 2. The frequency of proliferating CD8+ T cells in response to CMV pp65 peptides is not different between young and elderly people.

PBMCs were purified from the peripheral blood of young (age ≤ 40) and elderly (age ≥ 65) donors infected with CMV and stained with CFSE. Stained cells were stimulated for 7 days with or without a CMV pp65 peptide pool. Cell proliferation was analyzed on an LSRII® flow cytometer. (A) Representative data showing CD8+ T cell proliferation in response to CMV pp65 peptides. (B) The frequency of CD8+ T cells that proliferated in response to CMV pp65 peptides in young (n = 11) and elderly (n =15) people. Bars and error bars indicate mean and SEM, respectively. (C–D) Correlation of the frequencies of proliferating and cytokine producing CD8+ T cells in young and elderly people. P values were obtained using the unpaired t-test (B) and the Pearson correlation analysis (C–D).

3.3. The effects of aging and CMV-infectious status on plasma IL-27 levels

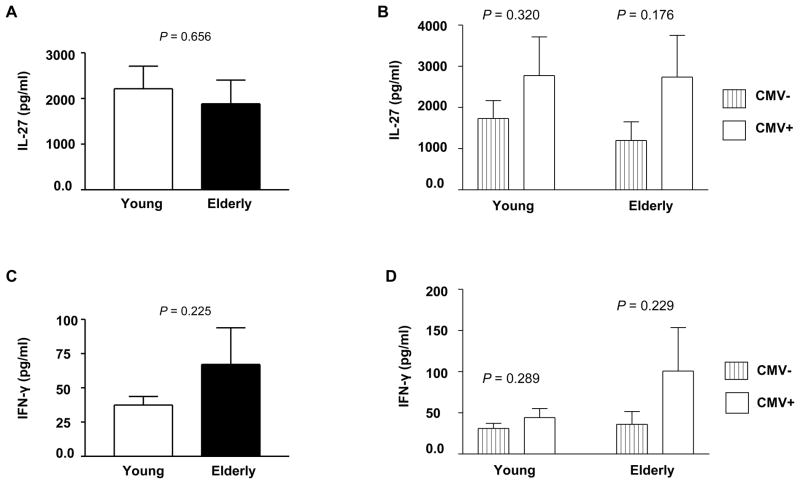

The cytokine IL-27 has both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties, and viral infections can induce the production of this cytokine [16, 24, 25]. However, it is unknown whether aging and CMV-infectious status can affect IL-27 levels in peripheral blood of humans. Plasma IL-27 levels were not different between young and elderly people (mean ± SEM, 2,213 pg/ml ± 495 vs. 1,883 pg/ml ± 522, P = 0.656) (Figure 3A). There was a trend towards increased plasma IL-27 levels in young people infected with CMV compared to their counterparts uninfected with CMV although this difference was not statistically different (mean ± SEM, 2,774 pg/ml ± 940 vs. 1,730 pg/ml ± 439, P = 0.320) (Figure 3B). A similar finding was noticed in elderly people infected and uninfected with CMV (mean ± SEM, 2,740 pg/ml ± 1,012 vs. 1,196 pg/ml ± 454, P = 0.176) (Figure 3B). We also measured IFN-γ levels in young and elderly people infected and uninfected with CMV in that IL-27 is known to promote the production of IFN-γ from T cells [16]. Elderly people appeared to have a trend towards increased levels of IFN-γ compared to young people although the difference was not statistically significant (mean ± SEM, 67.1 pg/ml ± 26.7 vs. 37.5 pg/ml ± 6.2, P = 0.225) (Figure 3C). Similar to IL-27 levels, there was a trend toward increased IFN-γ levels in young and elderly people infected with CMV compared to their counterparts uninfected with this virus. However, none of these differences were statistically significant (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. The effect of aging and CMV-infectious status on plasma IL-27 and IFN-γ levels.

Plasmas were obtained from peripheral blood of young (age ≤ 40) and elderly (age ≥ 65) people. Seropositivity for CMV was determined. Plasma IL-27 and IFN-γ levels were measured by ELISA. (A) Plasma IL-27 levels in young (n = 67) and elderly (n = 45) people. (B) Plasma IL-27 levels in CMV-uninfected (n = 36) and -infected (31) young people as well as in CMV-uninfected (n = 25) and –infected (n = 20) elderly people. (C) Plasma IFN-γ levels in young (n = 66) and elderly (n = 50). (D) Plasma IFN-γ levels in CMV-uninfected (n = 34) and -infected (n = 32) young people as well as in CMV-uninfected (n = 26) and -infected (n = 24) elderly people. Bars and error bars indicate mean and SEM, respectively. P values were obtained using the unpaired t-test.

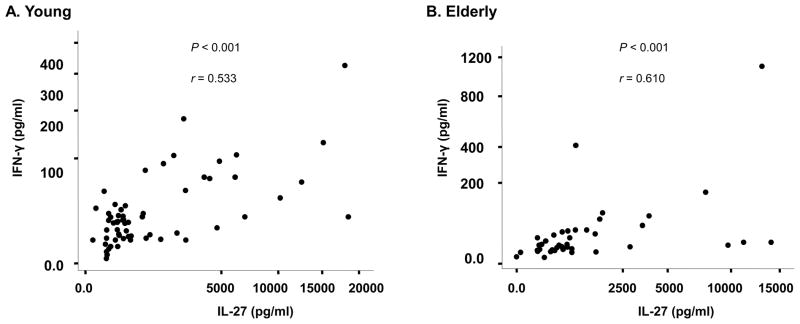

3.4. IL-27 levels correlate with IFN-γ levels in plasmas regardless of age and CMV-infectious status

We next determined whether IL-27 levels in blood correlated with IFN-γ levels in young and elderly people. Of interest, individuals who had higher levels of IL-27 also had higher levels of IFN-γ. This correlation was found in both young and elderly people (r = 0.533 and 0.610, respectively, P < 0.001 for both groups) (Figure 4). In addition, the same correlation was noticed in young and elderly people regardless of CMV infectious status (Table 1). Our findings indicate the presence of the biological link between IL-27 and IFN-γ levels in blood as well as the maintenance of such a link with aging and CMV infection.

Figure 4. Plasma levels of IL-27 and IFN-γ correlate in young and elderly people.

Plasmas were obtained from peripheral blood of young (age ≤ 40, n = 61) and elderly (age ≥ 65, n = 44) people. Seropositivity for CMV was determined. Plasma IL-27 and IFN-γ levels were measured by ELISA. P values were obtained using the Spearman correlation analysis.

Table 1.

Correlation of IL-27 and IFN-γ levels in plasmas of CMV-infected and uninfected young and elderly people.

| Correlation coefficient | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Young | CMV uninfected (n = 30) | 0.414 | 0.023 |

| CMV infected (n = 31) | 0.685 | < 0.001 | |

| Elderly | CMV uninfected (n = 25) | 0.500 | 0.011 |

| CMV infected (n = 19) | 0.740 | < 0.001 |

P values were obtained by Spearman correlation analysis.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we investigated whether young and elderly people infected with CMV had similar levels of CD8+ T cell cytokine production and proliferation in response to a immunodominant CMV pp65 peptide pool given the role of CD8+ T cells in controlling viral infection and the association of CMV with immunosenescence [1, 30, 31]. In addition, we determined the effects of aging and CMV-infectious status on plasma levels of IL-27 as well as on its relationship to IFN-γ in that IL-27 can promote the production of IFN-γ [16]. The results of our study show that young and elderly people had similar levels of CD8+ T cell proliferation, and IFN-γ and TNF-α production in response to CMV pp65 peptides. Plasma levels of IL-27 were similar between the two groups although CMV-infected young and elderly people had a trend towards increased levels of IL-27, which was not statistically significant. Regardless of aging and CMV-infectious status, plasma levels of IL-27 correlated highly with plasma levels of IFN-γ. These findings suggest the maintenance of CMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cell response with aging as well as the sustaining of circulatory IL-27 levels and its biological link to IFN-γ in young and elderly people, irrespective of CMV infection.

Alterations in the immune system occur with aging. These alterations include “inflammaging” that refers to the condition associated with chronic elevation of inflammatory molecules such as IL-6 in human aging [32, 33]. Although the exact mechanisms for such alterations are not fully understood, the potential implication of CMV which establishes latent infection has been suggested in human immunosenescence [30]. Indeed, elderly people infected with CMV had the expansion of functionally exhausted memory CD8+ T cells compared to elderly people uninfected with this virus [8, 30, 31, 34]. Also, increased mortality, including that associated with cardiovascular disease, was found in elderly people infected with CMV [35, 36]. Previous studies measuring cytokine production of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells in young and elderly people showed contradictory results. Some studies reported an age-associated decrease in the frequency of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in response to the HLA-A2-restricted CMV pp65 peptide [12, 13] while others showed an increased frequency of the cytokine-producing cells [8, 11, 14]. In our study, we measured the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as cell proliferation in CD8+ T cells after stimulating PBMCs with a CMV pp65 peptide pool. The results of our study showed that young and elderly people had no difference in the frequency of CD8+ T cells that produced the cytokines and proliferated in response to the CMV pp65 peptide pool. Of interest, the frequency of CD8+ T cells producing these cytokines correlated with the frequency of proliferating CD8+ T cells in response to the same viral peptides in young people but not in elderly people, implying an age-associated alteration in such relationship. Overall, our findings suggest that the capacity to mount CMV-specific CD8+ T cell responses is preserved with aging, providing an immunological explanation for why aging is not associated with an increased incidence of symptomatic CMV reactivation.

The cytokine IL-27 is produced primarily by innate immune cells. Viruses including influenza A and hepatitis B viruses induced the production of IL-27 [24, 25]. In fact, patients infected with hepatitis B virus had increased levels of IL-27 in blood compared to healthy controls [25]. Also, CMV is known to induce cytokine production from human monocytes [37]. Thus, it is possible that CMV could affect the production of IL-27 from innate immune cells. In our study, there was a trend towards increased levels of plasma IL-27 in individuals infected with CMV compared to the ones uninfected with this virus, although this difference was not statistically significant. IL-27 is known to promote IFN-γ production from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [17, 18]. This effect is likely mediated by the up-regulation of the transcription factor T-bet with the capacity to increase IFN-γ production [38]. Having such an effect on IFN-γ production, IL-27 could increase T cell- and natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity against tumors and hepatitis virus C [39–42]. In addition, IL-27 has anti-viral effect against HIV [43]. In fact, IL-27 augmented effector CD8+ T cell generation with enhanced expression of the cytotoxic molecule granzyme B [44]. In our study, we noticed a strong correlation of IL-27 and IFN-γ levels in plasmas of young and elderly people, supporting the biological link of these two cytokines as well as the maintenance of such a link with aging.

In conclusion, our study shows that young and elderly people had similar levels of CD8+ T cell proliferation, and IFN-γ and TNF-α production in response to the immunodominant CMV pp65 peptides. Plasma levels of IL-27 were also similar between the two groups. Although CMV-infected young and elderly people had a trend towards increased levels of IL-27 compared to their counterparts uninfected with this virus, such differences were not statistically significant. Regardless of aging and CMV-infectious status, plasma levels of IL-27 correlated highly with plasma levels of IFN-γ, indicating the biological connection of the two cytokines. These findings suggest the maintenance of CMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cell response with aging as well as the sustaining of circulatory IL-27 levels and its biological link to IFN-γ in young and elderly people irrespective of CMV infection.

Highlights.

CMV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation and cytokine production did not alter with age

Young and elderly people had similar levels of plasma IL-27

CMV-infected young and elderly people had an increased trend of plasma IL-27 levels

Correlation of IL-27 and IFN-γ occurred irrespective of age and CMV-infectious status

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Amy Shelton, Ms. Laurie Kramer and Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (UL1 RR024139) for assisting in the recruitment of human subjects. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG028069, AG030834 to IK). Insoo Kang is a participant in the World Class University Program of Republic of Korea.

Abbreviations

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- TCR

T cell receptor

- EBI3

Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene

- Th

T helper

- DCs

dendritic cells

- EAE

experimental allergic encephalitis

- CIA

collagen-induced arthritis

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate

- SEM

standard error of mean

- NK

natural killer

Footnotes

Competing Interests.

The authors have no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olson MR, Russ BE, Doherty PC, Turner SJ. The role of epigenetics in the acquisition and maintenance of effector function in virus-specific CD8 T cells. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:519–26. doi: 10.1002/iub.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billiau A, Matthys P. Interferon-gamma: a historical perspective. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harty JT, Tvinnereim AR, White DW. CD8+ T cell effector mechanisms in resistance to infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:275–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guidotti LG, Ishikawa T, Hobbs MV, Matzke B, Schreiber R, Chisari FV. Intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolich-Zugich J. Ageing and life-long maintenance of T-cell subsets in the face of latent persistent infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:512–22. doi: 10.1038/nri2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbar AN, Fletcher JM. Memory T cell homeostasis and senescence during aging. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Effros RB, Cai Z, Linton PJ. CD8 T cells and aging. Crit Rev Immunol. 2003;23:45–64. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v23.i12.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan N, Shariff N, Cobbold M, Bruton R, Ainsworth JA, Sinclair AJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8 T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J Immunol. 2002;169:1984–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch S, Larbi A, Ozcelik D, Solana R, Gouttefangeas C, Attig S, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection: a driving force in human T cell immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1114:23–35. doi: 10.1196/annals.1396.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weekes MP, Carmichael AJ, Wills MR, Mynard K, Sissons JG. Human CD28-CD8+ T cells contain greatly expanded functional virus-specific memory CTL clones. J Immunol. 1999;162:7569–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almanzar G, Schwaiger S, Jenewein B, Keller M, Herndler-Brandstetter D, Wurzner R, et al. Long-term cytomegalovirus infection leads to significant changes in the composition of the CD8+ T-cell repertoire, which may be the basis for an imbalance in the cytokine production profile in elderly persons. J Virol. 2005;79:3675–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3675-3683.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Zheng W, Wikby A, Remarque EJ, Pawelec G. Dysfunctional CMV-specific CD8(+) T cells accumulate in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:607–13. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadrup SR, Strindhall J, Kollgaard T, Seremet T, Johansson B, Pawelec G, et al. Longitudinal studies of clonally expanded CD8 T cells reveal a repertoire shrinkage predicting mortality and an increased number of dysfunctional cytomegalovirus-specific T cells in the very elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176:2645–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vescovini R, Biasini C, Fagnoni FF, Telera AR, Zanlari L, Pedrazzoni M, et al. Massive load of functional effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against cytomegalovirus in very old subjects. J Immunol. 2007;179:4283–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wojno ED, Hunter CA. New directions in the basic and translational biology of interleukin-27. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida H, Nakaya M, Miyazaki Y. Interleukin 27: a double-edged sword for offense and defense. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1295–303. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao Y, Doodes PD, Glant TT, Finnegan A. IL-27 induces a Th1 immune response and susceptibility to experimental arthritis. J Immunol. 2008;180:922–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider R, Yaneva T, Beauseigle D, El-Khoury L, Arbour N. IL-27 increases the proliferation and effector functions of human naive CD8+ T lymphocytes and promotes their development into Tc1 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:47–59. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, El-Behi M, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Li H, Yu S, et al. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1372–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stumhofer JS. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:1363–71. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, et al. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niedbala W, Cai B, Wei X, Patakas A, Leung BP, McInnes IB, et al. Interleukin 27 attenuates collagen-induced arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1474–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Wang G, Sun B, Li H, Mu L, Wang Q, et al. Interleukin-27 suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis during bone marrow stromal cell treatment. J Autoimmun. 2008;30:222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu L, Cao Z, Chen J, Li R, Cao Y, Zhu C, et al. Influenza A Virus Induces Interleukin-27 through Cyclooxygenase-2 and Protein Kinase A Signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11899–910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu C, Zhang R, Liu L, Rasool ST, Mu Y, Sun W, et al. Hepatitis B virus enhances interleukin-27 expression both in vivo and in vitro. Clin Immunol. 2009;131:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang I, Hong MS, Nolasco H, Park SH, Dan JM, Choi JY, et al. Age-associated change in the frequency of memory CD4+ T cells impairs long term CD4+ T cell responses to influenza vaccine. J Immunol. 2004;173:673–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong MS, Dan JM, Choi JY, Kang I. Age-associated changes in the frequency of naive, memory and effector CD8+ T cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:615–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HR, Hong MS, Dan JM, Kang I. Altered IL-7R{alpha} expression with aging and the potential implications of IL-7 therapy on CD8+ T-cell immune responses. Blood. 2006;107:2855–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang KA, Kim HR, Kang I. Aging and human CD4(+) regulatory T cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:509–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E. Role of CMV in immune senescence. Virus Res. 2011;157:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee WW, Shin MS, Kang Y, Lee N, Jeon S, Kang I. The relationship of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection with circulatory IFN-alpha levels and IL-7 receptor alpha expression on CD8(+) T cells in human aging. Cytokine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh T, Newman AB. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:319–29. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vasto S, Colonna-Romano G, Larbi A, Wikby A, Caruso C, Pawelec G. Role of persistent CMV infection in configuring T cell immunity in the elderly. Immun Ageing. 2007;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH, Tilvis RS. Cytomegalovirus antibody level and mortality among community-dwelling older adults with stable cardiovascular disease. Jama. 2009;301:380–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts ET, Haan MN, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Cytomegalovirus antibody levels, inflammation, and mortality among elderly Latinos over 9 years of follow-up. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:363–71. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan G, Bivins-Smith ER, Smith MS, Smith PM, Yurochko AD. Transcriptome analysis reveals human cytomegalovirus reprograms monocyte differentiation toward an M1 macrophage. J Immunol. 2008;181:698–711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owaki T, Asakawa M, Morishima N, Hata K, Fukai F, Matsui M, et al. A role for IL-27 in early regulation of Th1 differentiation. J Immunol. 2005;175:2191–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hisada M, Kamiya S, Fujita K, Belladonna ML, Aoki T, Koyanagi Y, et al. Potent antitumor activity of interleukin-27. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1152–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiyo M, Shimozato O, Yu L, Kawamura K, Iizasa T, Fujisawa T, et al. Expression of IL-27 in murine carcinoma cells produces antitumor effects and induces protective immunity in inoculated host animals. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:437–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oniki S, Nagai H, Horikawa T, Furukawa J, Belladonna ML, Yoshimoto T, et al. Interleukin-23 and interleukin-27 exert quite different antitumor and vaccine effects on poorly immunogenic melanoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6395–404. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsui M, Moriya O, Belladonna ML, Kamiya S, Lemonnier FA, Yoshimoto T, et al. Adjuvant activities of novel cytokines, interleukin-23 (IL-23) and IL-27, for induction of hepatitis C virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice. J Virol. 2004;78:9093–104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9093-9104.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenwell-Wild T, Vazquez N, Jin W, Rangel Z, Munson PJ, Wahl SM. Interleukin-27 inhibition of HIV-1 involves an intermediate induction of type I interferon. Blood. 2009;114:1864–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morishima N, Owaki T, Asakawa M, Kamiya S, Mizuguchi J, Yoshimoto T. Augmentation of effector CD8+ T cell generation with enhanced granzyme B expression by IL-27. J Immunol. 2005;175:1686–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]