Abstract

Background

Wide-margin resections are an accepted method for treating soft tissue sarcoma. However, a wide-margin resection sometimes impairs function because of the lack of normal tissue. To preserve the normal tissue surrounding a tumor, we developed a less radical (ie, without a wide margin) surgical procedure using adjunctive photodynamic therapy and acridine orange for treating soft tissue sarcoma. However, whether this less radical surgical approach increases or decreases survival or whether it increases the risk of local recurrence remains uncertain.

Questions/purposes

We determined the survival, local recurrence, and limb function outcomes in patients treated with a less radical approach and adjunctive acridine orange therapy compared with those who underwent a conventional wide-margin resection.

Methods

We treated 170 patients with high-grade soft tissue sarcoma between 1999 and 2009. Fifty-one of these patients underwent acridine orange therapy. The remaining 119 patients underwent a conventional wide-margin resection for limb salvage surgery. We recorded the survival, local recurrence, and functional score (International Society of Limb Salvage [ISOLS]) score) for all the patients.

Results

The 10-year overall survival rates in the acridine orange therapy group and the conventional surgery group were 68% and 63%, respectively. The 10-year local recurrence rate was 29% for each group. The 5-year local recurrence rates for Stages II, III, and IV were 8%, 36%, and 40%, respectively, for the acridine orange group and 13%, 27%, and 33%, respectively, for the conventional surgery group. The average ISOLS score was 93% for the acridine orange group and 83% for the conventional therapy group.

Conclusion

Acridine orange therapy has the potential to preserve limb function without increasing the rate of local recurrence. This therapy may be useful for eliminating tumor cells with minimal damage to the normal tissue in patients with soft tissue sarcoma.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of the levels of evidence.

Introduction

High-grade soft tissue sarcoma resection with an adequate wide margin reportedly inhibits local tumor recurrence and improves patient prognosis compared with a marginal or intralesional margin [8, 11, 13, 14, 41, 44]. However, if the tumors are located near major nerves, vessels, bones, or joints (ie, the knee, hip, shoulder, or elbow), these structures might need to be sacrificed during a wide-margin resection, resulting in various degrees of impaired limb function. Furthermore, the resection of tumors with a wide resection margin is sometimes difficult, and postoperative radiation therapy or brachytherapy might be required because of a positive margin status. The long-term effects of radiation therapy can include fibrosis, edema, fractures, and contractures, all of which can substantially impair limb function. Thus, patients frequently experience serious limb dysfunction after surgery [6, 7, 31, 42, 45]. Adjuvant therapies that could reduce the need for a wide surgical margin without increasing the incidence of local recurrence could enable better limb function after the resection of high-grade soft tissue sarcomas.

We have focused on adjuvant photodynamic therapy with photosensitizers as a neoadjuvant therapy to kill tumor cells and thereby reduce the surgical margin. Several photosensitizers are used for cancer treatment. Intravenously administered hematoporphyrin was the first photodynamic therapy agent approved for clinical use in 1993 for treating bladder cancer during endoscopic surgery [38]. The use of hematoporphyrin, marketed under the trade name Photofrin (QLT Inc, Vancouver, Canada), was extended to include the treatment of cancers of the skin [43], lung [24], esophagus [12], stomach [12], and uterus [30]. 5-Aminolevulinic acid has also been used for the treatment of skin cancer [2]. However, 1 or 2 days is required for these two photosensitizers to be delivered to the cancer cells after intravenous injection.

In 1990, we began testing a promising new photosensitizer, acridine orange [10, 16, 17, 21–23], for its usefulness in treating musculoskeletal sarcoma. Acridine orange specifically binds to malignant tumors and immediately accumulates in tumor cells [16, 21–23, 29]. It can be delivered to tumor cells quickly through local administration. Acridine orange binds densely to lysosomes and acidic vesicles, which are rich in tumor cells [29], and is therefore useful for visualizing tumor cells during surgery under a fluorescence microscope. Furthermore, it has a strong cytocidal effect on tumor cells after a single session of blue light excitation or low-dose radiation, allowing residual tumor cells located deep inside the body to be killed [10].

Based on the results of basic studies, in July 1999 we began to develop a therapeutic approach that combined a less radical approach without the intent to achieve a wide margin but supplemented with adjunctive acridine orange photodynamic surgery, photodynamic therapy, and radiodynamic therapy [18–20, 26–28, 32, 47]. Acridine orange therapy can potentially reduce the surgical margin by visualizing tumor cells, thereby enabling the normal surrounding tissue to be preserved. However, given the fact that this approach used a less radical surgical technique, rather than a wide-margin resection, it was unclear whether the overall survival would be higher with this approach and whether the rate of local recurrence would be increased.

We therefore examined the survival, local recurrence, and limb function outcomes in patients who were treated with a less radical approach and adjunctive acridine orange therapy compared with those who underwent a conventional wide-margin resection.

Patients and Methods

From 1999 to 2009, we treated 236 patients with primary soft tissue sarcomas of the limbs, girdle, or trunk. We excluded eight patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma, five with soft tissue sarcoma that could not be resected without amputation, and 53 patients with small superficial tumors or low-grade sarcomas. These exclusions left 170 patients; acridine orange therapy was performed in 51 of these patients, and the remaining 119 patients underwent a conventional wide-margin resection for limb salvage surgery (Table 1). This clinical trial for acridine orange therapy was not designed as a randomized study. Rather, after a full explanation of the acridine orange therapy, a conventional wide-margin resection, and the purpose of the study, each patient and a family member could select the treatment they preferred, and each provided written informed consent before study participation. Briefly acridine orange therapy was described as a procedure in which the surgical margin would be located close to the tumor, and the acridine orange therapy would be used to kill the tumor cells near the margin. We further explained that this therapy was being studied as a clinical trial, and the patients were able to choose to undergo a conventional wide marginal resection with the reconstruction of artificial vessels, a prosthesis, or radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Patient distributions, histological diagnosis, location, and AJCC staging

| Acridine orange therapy group (n = 51) | Wide-margin resection group (n = 119) | Total (n = 170) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 28 | 66 | 94 | ||

| Women | 23 | 53 | 76 | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Range | 0–87 | 0–85 | *p = 0.2 | ||

| Mean | 44 | 54 | |||

| Histological diagnosis | Synovial sarcoma | 9 | MFH | 29 | |

| MFH | 8 | Liposarcoma | 26 | ||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 7 | Synovial sarcoma | 13 | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 6 | Fibrosarcoma | 12 | ||

| Fibrosarcoma | 4 | Leiomyosarcoma | 10 | ||

| Liposarcoma | 4 | Extraskeletal myxoid | |||

| Extraskeletal myxoid | Chondrosarcoma | 6 | |||

| Chondrosarcoma | 4 | Undifferentiated sarcoma | 6 | ||

| Ewing/PNET | 4 | Malignant granular cell tumor | 4 | ||

| Other | 5 | Other | 13 | ||

| Location (%) | |||||

| Upper limb | 11 (22%) | 19 (16%) | 30 | ||

| Lower limb | 28 (55%) | 60 (50%) | 88 | ||

| Trunk | 12 (23%) | 40 (34%) | 52 | ||

| AJCC stage (%) | |||||

| II | 13 (25%) | 43 (36%) | 56 | ||

| III | 25 (50%) | 62 (52%) | 87 | ||

| IV | 13 (25%) | 14 (12%) | 27 | ||

| Followup (months) | |||||

| Range | 3–131 | 3–121 | †p = 0.65 | ||

| Mean | 48 | 46 | |||

* p value of Student’s t-test analysis; †p value of Welch t-test analysis; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; MFH = malignant fibrous histiocytoma; PNET = primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Before surgery, we selected candidates for acridine orange therapy based on the following indications: (1) the tumor was in contact with major nerves or vessels; (2) the tumor was in contact with bone but did not show signs of massive invasion; (3) the MRI results showed a low degree of invasiveness (the tumor margin could be identified on the MRI images) to the normal surrounding tissues; (4) the tumor was in contact with a major organ (ie, knee, hip, shoulder, elbow, inguinal tracts, bone, or tendons); and (5) the tumor biopsy sample showed sensitivity to acridine orange. Tumor samples that were resected during an open biopsy were stained with acridine orange, and the sensitivity to acridine orange was assessed using analytical software [29]. All five criteria had to be satisfied for the patient to be a candidate for acridine orange therapy.

Of the 170 patients, five patients were eligible for acridine orange therapy but chose to undergo a conventional wide-margin resection with 40 to 60 Gy of radiation therapy after surgery. Thirty-four patients who agreed to undergo acridine orange radiodynamic therapy received low-dose (5 Gy) radiotherapy after the closure of the surgical wound without washing out the acridine orange solution (Table 2). Thirty-two patients in the wide-margin resection group received radiation therapy or brachytherapy after surgery. These 32 patients included five patients who refused acridine orange therapy and 27 patients whose surgical margins were assessed as being less than 5 mm according to macroscopic findings or pathological findings. Of the 170 patients, 51 patients received acridine orange therapy and 119 patients received a wide-margin resection. We compared the clinical results for survival, local recurrence, and limb function between the two groups. The mean ages of the patients in the acridine orange therapy group and the wide-margin resection group were 44 and 54 years, respectively, and the minimum followup was 3 months (mean, 48 months; range, 3–131 months) and 3 months (mean, 46 months; range, 3–121 months), respectively. None of the patients were lost to followup. None of the patients were recalled specifically for the purposes of this study; all the data were obtained from the patients’ medical records. The ethics committee of our university hospital approved this study.

Table 2.

Procedures and adjuvant therapies

| Acridine orange therapy group (n = 51) | Wide-margin resection group (n = 119) | Total (n = 170) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures | PDS + PDT | 17 | Wide-resection | 114 | |

| PDS + PDT + RDT | 34 | Wide-resection + prosthesis | 4 | ||

| Wide-resection + RBG | 1 | ||||

| Adjuvant therapy | Chemotherapy | 26 | Chemotherapy | 28 | |

| Radiation therapy | 15 | ||||

| Brachytherapy | 17 | ||||

| Tumor size (mean) | 9.4 cm | 8.0 cm | p = 0.06 | ||

PDS = photodynamic surgery; PDT = photodynamic therapy; RDT = radiodynamic therapy; RBG = intraoperative irradiated auto bone graft; Chemotherapy = mainly performed with Adriamycin and ifosfamide. For rhabdomyosarcoma cases, chemotherapy with vincristine, actinomycin-D, and cyclophosphamide was performed following the regimen of Japanese rhabdomyosarcoma study.

No difference in age or the followup period was observed between the two groups when examined using a Student’s or Welch t-test (Table 1). Both groups included American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage IV patients. Thirty-four patients who agreed to undergo acridine orange radiodynamic therapy received 5 Gy of radiation immediately after surgery (Table 2). We determined the tumor size according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, Version 1.1 [4]. The average tumor sizes in the acridine orange therapy group and wide-margin resection group were 9.4 cm and 8.0 cm, respectively. The average tumor size tended to be larger in the acridine orange therapy group than in the wide-margin resection group (95% CI, 8.3–10.7 versus 7.1–8.9). Thirteen patients in the acridine orange therapy group and nine patients in the wide-margin resection group were recurrent cases at the time of the definitive operation. The acridine orange therapy group included 13 patients with AJCC Stage IV disease (25%), whereas the wide-margin resection group included 14 patients with Stage IV disease (12%) at the time of referral.

All the patients with soft tissue sarcomas who underwent acridine orange therapy received intentional marginal or intralesional tumor excisions around the major nerves, vessels, or organs. These procedures were used to minimize damage to the intact muscles and bones as well as the major nerves and vessels that were in close contact with the tumor and were important for the maintenance of limb function. Next, we performed microscopic curettage using an ultrasonic surgical scalpel (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). We sprayed a 1-μg/mL solution of acridine orange (Sigma Aldrich Co, St Louis, MO, USA) over the resected surfaces using a syringe; excess solution was removed with saline. We then observed the fluorescence using a surgical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an interference filter (450–490 nm) to select the blue light emitted by a xenon lamp and an absorption filter (>520 nm) to allow for the observation of the green acridine orange fluorescence under fluorescence surgical microscopy. Microscopic curettage was then repeated until the green fluorescence had disappeared completely from the remnant tumor mass. Acridine orange photodynamic therapy was subsequently applied to the area of tumor curettage by illuminating the area with > 100,000 lx of unfiltered light from a xenon lamp for 10 minutes followed once again by fluorescence surgical microscopy.

A wide-margin resection was performed with a 2- to 5-cm surgical margin [13, 14], which is regarded as a safe surgical margin. When the surgical margins of the patients in the wide-margin group were assessed as being less than 5 mm on macroscopic findings or pathological findings, including those patients with positive margins, 40 to 60 Gy of radiation therapy or brachytherapy was performed after the surgery. Between 1999 and 2001, we performed brachytherapy for patients in the wide-margin resection group who had a surgical margin of less than 5 mm macroscopically at the closest point [35, 46]. In the wide-margin resection group, four patients required two total femur prostheses, one required a proximal femur prosthesis, one required a proximal tibia prosthesis, and one required an intercalary radiated bone autograft because of severe bone defects.

We typically evaluated the patients according to the following schedule: 2 weeks postoperatively, followed by 6 weeks, 3 months, and then every 3 months for 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. Functional evaluations were obtained for all 51 patients who underwent acridine orange therapy and 119 patients who underwent a conventional wide-margin resection using the revised 30-point functional classification system established by the International Society of Limb Salvage (ISOLS) [40] and the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society [5]. For lower limbs, the functional score measures pain, function, emotional acceptance, use of walking support, walking ability, and gait. For upper limbs, the functional score measures pain, function, emotional acceptance, hand positioning, dexterity, and lifting ability. Each of these six parameters is given a value ranging from 0 to 5 according to specific criteria. The individual scores are added to obtain an overall functional score with a maximum of 30 points. The overall functional score was then expressed as a percentage of normal. To compare the acridine orange therapy group with the wide-margin resection group, we collected the following data: age, sex, tumor size, type of definitive surgery (intralesional or marginal resection with or without acridine orange radiodynamic therapy), status as primary or recurrent disease at the time of definitive surgery, and AJCC stage (II, III, or IV) [34]. Complications were recorded and classified according to the Dindo classification [3]. Minor complications were managed clinically and major complications required surgical intervention.

We defined local recurrence-free survival as the time from study entry until the local recurrence of disease or until the last contact. Survival was defined as the time from study entry until death or the last contact. We calculated the local recurrence-free survival and the 5- and 10-year survival rates using Kaplan-Meier analysis. The survival rates and local recurrence rates in both groups were assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimates and differences in the rates were determined using log-rank test and StatView, Version 5.0 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA). A multivariate analysis was performed to determine potential prognostic factors with respect to the two study end points: time until death and time until local recurrence. In the multivariate analysis, local control and survival were examined using the Cox proportional hazards model based on the age at the time of diagnosis, sex, tumor size, type of definitive surgery (surgical margin or photodynamic surgery), status as primary or recurrent disease at the time of definitive surgery, and AJCC stage (II and III versus IV).

Results

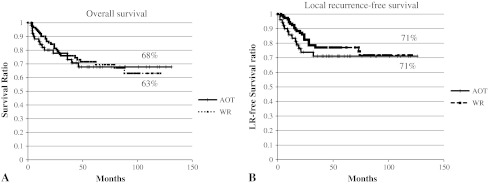

The 10-year overall survival rates in the acridine orange therapy group and the wide-margin resection group were similar (p = 0.75), 68% and 63% (95% CI, 54%–81% versus 51%–76%, respectively). The 10-year local recurrence rate was also similar (p = 0.36; 95% CI, 15%–42% versus 17%–39%), 29% for each group (Fig. 1). We observed no differences in the overall survival rates between the acridine orange therapy and the wide-margin resection groups for each AJCC stage: the 5-year survival rates for patients with AJCC Stage II, III, and IV was 100%, 87%, and 0%, respectively, in the acridine orange therapy group and 95% (p = 0.41), 76% (p = 0.35), and 0% (p = 0.78), respectively, in the wide-margin resection group (Fig. 2A–B). The 5-year local recurrence-free rates for patients with Stage II, III, and IV disease were 92%, 64%, and 60%, respectively, in the acridine orange therapy group and 87%, 73%, and 67%, respectively, in the wide-margin resection group (Fig. 2C–D). Acridine orange therapy was not inferior to wide-margin resection in terms of survival and local recurrence control in each AJCC group.

Fig. 1A–B.

Kaplan-Meier analyses of overall survival (A) and local recurrence-free survival (B) are shown. The last followup examination was 131 months in the acridine orange therapy (AOT) group and 121 months in the wide-margin resection (WR) group. As of the last followup examination, 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for overall survival in the acridine orange therapy group and the wide-margin resection group were 54%–81% versus 51%–76%, respectively. The 95% CI for local recurrence was 15%–42% versus 17%–39%, respectively. Both overall survival and local recurrence-free survival were not significantly different between the acridine orange therapy group and the conventional wide-margin resection group.

Fig. 2A–D.

Effect of AJCC stage on overall survival in the acridine orange therapy (AOT) group (A) and the wide-margin resection (WR) group (B) and on local recurrence-free survival in the AOT group (C) and the WR group (D). The 95% CIs according to the disease stage were as follows: (A) AJCC Stage II, 100%–100%; Stage III, 73%–100%; Stage IV, 0%–0%; (B) Stage II, 88%–100%; Stage III, 48%–80%; Stage IV, 0%–0%; (C) Stage II, 78%–100%; Stage III, 44%–85%; Stage IV, 27%–93%; and (D) Stage II, 56%–98%; Stage III, 56%–83%; Stage IV, 33%–100%. No differences in the overall survival of the patients in the AOT group and the patients in the WR group were seen for the same AJCC stage. AJCC Stage II patients had better survival and local recurrence-free survival rates than the Stage III or IV patients in the same group. LR = local recurrence.

Regarding the complications after acridine orange therapy, no complications requiring surgical intervention were observed according to the Dindo classification [3].

The average ISOLS limb function score was higher (p = 0.02) in the acridine orange therapy group compared with that in the wide-margin resection group (93% versus 83%).

A larger tumor size predicted a poor overall survival and a higher risk of local recurrence, and AJCC Stage IV predicted a poor overall survival in the acridine orange therapy and the wide-margin resection groups (Table 3). Recurrence status was also a risk factor for subsequent local recurrence in the wide-margin resection group but not in the acridine orange therapy group. Furthermore, intralesional resection did not predict local recurrence or poor survival in the acridine orange therapy group. In the acridine orange therapy group, although the numbers of cases belonging to each histological subtype were relatively small, nine cases of synovial sarcoma had no local recurrence (0%), and only one local recurrence (14%) occurred in seven cases of rhabdomyosarcoma (Table 4).

Table 3.

Results of multivariate analysis for survival and local recurrence

| Survival | Local recurrence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk ratio | p value | 95% CI | Risk ratio | p value | 95% CI | |

| Acridine orange therapy group | ||||||

| Tumor size | 1.12 | 0.001 | 1.05–1.2 | 1.12 | 0.02 | 1.01–1.23 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.22 | 0.96–1 | 1.02 | 0.06 | 1–1.05 |

| Sex | 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.37–2.87 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 0.34–3.04 |

| Recurrence cases | 1.16 | 0.79 | 0.37–3.67 | 1.54 | 0.47 | 0.47–5.01 |

| AJCC IV | 24.2 | 0.0001 | 6.5–89.5 | 2.23 | 0.18 | 0.67–7.36 |

| AO-RDT | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.24–1.93 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.23–2.18 |

| Intraregional margin | 2.22 | 0.29 | 0.49–9.88 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 0.17–1.69 |

| Wide-margin resection group | ||||||

| Tumor size | 1.1 | 0.0006 | 1.04–1.16 | 1.13 | 0.009 | 1.05–1.2 |

| Age | 1 | 0.46 | 0.98–1.02 | 1 | 0.58 | 0.98–1 |

| Sex | 0.6 | 0.17 | 0.28–1.25 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.43–2.2 |

| Recurrence cases | 1.97 | 0.21 | 0.68–5.64 | 9.25 | 0.0001 | 3.54–24.2 |

| AJCC IV | 12.7 | 0.0001 | 5.9–27.4 | 2.37 | 0.16 | 0.69–8.1 |

| BTx versus RTx | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0.24–1.36 | 0.9 | 0.82 | 0.36–2.22 |

CI = confidence interval; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer staging; AO-RDT = radiodynamic therapy with acridine orange; BTx = brachytherapy; RTx = radiation therapy.

Table 4.

Local recurrence percentages in histological subtypes in acridine orange therapy

| Histological diagnosis | Local recurrence cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Acridine orange therapy (n = 51) | |

| Synovial sarcoma | 0/9 (0%) |

| MFH | 3/8 (38%) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1/7 (14%) |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 3/6 (50%) |

| Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma | 2/4 (50%) |

| PNET | 1/4 (25%) |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1/4 (25%) |

| Liposarcoma | 1/4 (25%) |

| Other | 1/5 (20%) |

MFH = malignant fibrous histiocytoma; PNET = primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Discussion

Limb salvage in patients with soft tissue tumors occurring in the extremities has now been established as a reasonable option without compromising long-term survival [6, 37, 44]. Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy also assist in providing a better prognosis [35, 46]. However, en bloc resection or wide tumor resection for high-grade soft tissue sarcomas that are in contact with critical muscles, vessels, nerves, bones, or joints can cause serious deficits in limb function [1, 39]. Some adjuvant therapies such as radiation therapy or brachytherapy can reduce the risk of local recurrence after tumor resections, but the effects of these adjuvant therapies are not superior to those of wide-margin resection [11, 14, 35, 46]. If the surgical margin can be reduced without local recurrence, postsurgical limb function can be maintained. To reduce the surgical margin, we have developed a therapeutic approach involving the use of acridine orange therapy [18–20, 26–28, 32, 47]. We therefore examined the survival, local recurrence, and limb function outcomes in patients treated with a less radical surgical approach and adjunctive acridine orange therapy compared with those who underwent a conventional wide-margin resection.

Our study had a number of limitations. First, because the present trial was not a randomized study comparing acridine orange therapy and wide-margin resection surgery, these therapies were difficult to compare strictly. However, the number of patients was reasonably large, and the distribution of AJCC stages, tumor sizes, and histological subtypes was similar within each group. Furthermore, a poorer survival and a larger number of local recurrences would be expected in the group with a marginal resection if the adjunctive acridine orange therapy was ineffective, yet we did not find this to be the case. Second, in the conventional wide-margin group, a large number of patients received postoperative radiation, presumably lowering the risk of local recurrence. Because positive-margin status after surgery is a risk factor for local recurrence [11, 15, 36, 41, 48], we used postoperative radiation therapy or brachytherapy in the wide-margin resection group if the surgical margin was positive or nearly positive. However, the long-term effects of radiation therapy (those effects occurring more than 1 year after the completion of therapy) generally involve fibrosis, necrosis, edema, fractures, and contractures, all of which can substantially impair limb function. Although postoperative radiation therapy in the wide-margin resection group would likely cause dysfunction because of long-term radiation effects, whether postoperative radiation therapy in the wide-margin resection group promoted better local tumor control or survival could not be decided based on the present study because the results of the two groups were not different with regard to local control or survival with the exception of limb function. Furthermore, acridine orange therapy was used in tumors that were in contact with major vessels, requiring conventional radiation therapy for a wide-margin resection. Third, for the acridine orange therapy group, we selected patients whose tumors were in contact with major nerves or vessels. The surgical margin of tumors in contact with major nerves or vessels tended to be closer to enable the preservation of the nerves or vessels; to avoid the risk associated with closer margins, preoperative chemotherapy was more frequently performed in the acridine orange group than in the wide-margin resection group (Table 2). Although the invasion of blood vessels by soft tissue sarcomas is a risk factor for a poor prognosis, chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas can improve the outcome [25]. On the other hand, the percentage of patients with AJCC Stage IV in the acridine orange therapy group (25%) was higher than that in the wide-margin resection group (12%) (Table 1). For these advanced tumors, preoperative chemotherapy tended to be performed more frequently. If the adjunctive acridine orange therapy for these aggressive AJCC Stage IV tumors had been ineffective, a poorer survival and a larger number of local recurrences would have been expected. Furthermore, because of the criteria used as indicators for acridine orange therapy, rhabdomyosarcomas, synovial sarcomas, PNETs, or tumors that are commonly located in contact with major joints, nerves, or vessels and that occur in young patients tend to be selected for acridine orange therapy. Although these tumors in contact with critical structures are associated with a risk of local recurrence because of the relatively close margin, these tumors included so-called “chemosensitive tumors” such as rhabdomyosarcoma or PNET. Although chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas can improve the survival or local recurrence outcomes, such advanced tumors requiring chemotherapy were more frequently selected to undergo acridine orange therapy. The important point of this comparison study is to show similarity between the two groups in terms of the overall survival and local recurrence outcomes.

We found similar overall survival and local recurrence periods in the acridine orange therapy group and the wide-margin resection group. The 10-year overall survival rate for the acridine orange therapy group and the wide-margin resection groups were 68% and 63%, respectively, and the 10-year local recurrence rate was 29% for each group. The overall 5-year survival rates in a large series of patients with high-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the limb or trunk reportedly range from 66% to 76% (Table 5) [9, 33, 36, 41]. Therefore, the clinical results for acridine orange therapy are comparable to those for wide-margin resection.

Table 5.

Significant prognostic factors for survival in patients with soft tissue sarcoma from large series

| Author/institution | Number | Population characteristics | Overall survival | Prognostic factors for poor survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pisters et al/MSKCC [35] | 1041 | Soft tissue sarcoma, limb | 76% (5-year) | Size > 10 cm High grade Deep location Histological subtype: leiomyosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor Positive surgical margin |

| Gustafson/SSG [9] | 508 | Soft tissue sarcoma, limb or trunk | 66% (5-year) | Size > 10 cm High grade Deep location Tumor vascular invasion |

| Trovik et al/SSG [41] | 559 | Soft tissue sarcoma, limb or trunk | 72% (5-year) | Size > 7 cm High grade |

| Parsons et al/SEER [33] | 6215 | Soft tissue sarcoma, limb (nonmetastatic) | 75.6% (10-year) | Size > 5 cm High grade Histological subtype: leiomyosarcoma |

MSKCC = Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; SSG = Scandinavian Sarcoma Group; SEER = public-use release of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results tumor registry.

Perhaps more importantly, patients with microscopically positive surgical margins have an increased risk of local recurrence. Indeed, the margin status after surgical resection is an independent prognostic factor for local recurrence [11, 15, 36, 41, 48]. Regarding the surgical margin, although clinical judgment and interpretation of the MRI findings identify an apparent tumor margin, the judgments are obviously subjective. If MR images could detect a single or small number of tumor cells, the resection of tumors with a safe or adequate surgical margin would be easy. However, surgeons must decide on the surgical margins based on MRI or other imaging findings that cannot detect a single cell, relying instead on their experience and the available evidence. Determining appropriate safety margins can be difficult. Although we selected patients whose tumors did not exhibit “invasiveness” or “nonmassive invasiveness” on preoperative MR images, these terms do not necessarily imply that they are less aggressive. Furthermore, in our comparison of acridine orange therapy and wide-margin resection surgery, we found no difference in the overall survival or local recurrence despite the different surgical margins used in the two groups. One explanation for this finding is that acridine orange therapy has the advantage of making the tumor cells visible during surgery. Even if the tumor cannot be visualized because of its small size or deep-seated nature, the tumor cells can subsequently be killed using low-dose radiation therapy with acridine orange. Still, the preoperative judgment of surgical margins is not as perfect as the surgeons may believe, and the surgical margins for musculoskeletal tumors sometimes result in a partial intralesional or marginal margin. So, these advantages in acridine orange therapy and the results of this study indicate that acridine orange therapy is useful for local control after a closer margin or positive margin tumor resection and for preserving limb function in patients with high-grade soft tissue sarcomas.

Variables associated with poor long-term function after radiation therapy include large tumors, high-dose radiation, long radiation fields, and wound complications [39, 46]. In the acridine orange therapy group, we performed acridine orange radiodynamic therapy after surgery in 34 patients, but no complications requiring surgical intervention occurred [3]. Acridine orange radiodynamic therapy is a unique technique that has the potential to be useful as a high-dose radiation therapy without adverse complications. X-ray energy can excite acridine orange like a visible beam, and tumor cells exposed to acridine orange are killed even if they are deeply seated [10]. X-ray energy is accelerated by acridine orange in a manner such that low-dose radiation has an effect similar to that of high-dose radiation without the associated complications. Consequently, limb function can often be preserved in patients who receive acridine orange therapy.

Survival and local recurrence are affected by the tumor subtype and AJCC stage, as many previous articles have mentioned. Gustafson [9] suggested that a diagnosis of synovial sarcoma was a risk factor for reduced survival, but acridine orange therapy produced good local control and survival rates for patients with synovial sarcoma or rhabdomyosarcomas. Consequently, if acridine orange therapy is further refined and basic studies involving large numbers of patients are performed, this therapy could became an effective treatment for soft tissue sarcomas.

Our data suggest that acridine orange therapy may be useful for local control after reduction surgery in patients with soft tissue sarcoma compared with a conventional wide-margin resection. Even if the surgical margin is positive, acridine orange therapy can control local recurrence as conventional wide-margin resection. A less radical approach in combination with adjunctive acridine orange therapy can provide comparable survival, local recurrence, and limb function to a conventional wide-margin resection. Thanks to the preservation of normal tissue, better limb function can also be anticipated after acridine orange therapy compared with after a wide-margin resection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Atsumasa Uchida MD and Kunihiro Asanuma MD for their surgical management and data collection assistance.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Mie University Hospital, Mie, Japan.

References

- 1.Brooks AD, Gold JS, Graham D, Boland P, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF, Healey JH. Resection of the sciatic, peroneal, or tibial nerves: assessment of functional status. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:41–47. doi: 10.1245/aso.2002.9.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairnduff F, Stringer MR, Hudson EJ, Ash DV, Brown SB. Superficial photodynamic therapy with topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid for superficial primary and secondary skin cancer. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:605–608. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs B, Davis AM, Wunder JS, Bell RS, Masri BA, Isler M, Turcotte R, Rock MG. Sciatic nerve resection in the thigh: a functional evaluation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghert MA, Davis AM, Griffin AM, Alyami AH, White L, Kandel RA, Ferguson P, O’Sullivan B, Catton CN, Lindsay T, Rubin B, Bell RS, Wunder JS. The surgical and functional outcome of limb-salvage surgery with vascular reconstruction for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:1102–1110. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, Seddon B. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi: 10.1155/2010/506182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafson P. Soft tissue sarcoma. Epidemiology and prognosis in 508 patients. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1994;259:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashiguchi S, Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Takeshita H, Hashiba M, Nishimura T, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Acridine orange excited by low-dose radiation has a strong cytocidal effect on mouse osteosarcoma. Oncology. 2002;62:85–93. doi: 10.1159/000048251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbert SH, Corn BW, Solin LJ, Lanciano RM, Schultz DJ, McKenna WG, Coia LR. Limb-preserving treatment for soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. The significance of surgical margins. Cancer. 1993;72:1230–1238. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1230::aid-cncr2820720416>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato H, Horai T, Furuse K, Fukuoka M, Suzuki S, Hiki Y, Ito Y, Mimura S, Tenjin Y, Hisazumi H, et al. Photodynamic therapy for cancers: a clinical trial of porfimer sodium in Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993;84:1209–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb02823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi N, Ahmed AR, Matsumoto S, Manabe J, Matsushita Y. The concept of curative margin in surgery for bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:165–172. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200402000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaguchi N, Matumoto S, Manabe J. New method of evaluating the surgical margin and safety margin for musculoskeletal sarcoma, analysed on the basis of 457 surgical cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1995;121:555–563. doi: 10.1007/BF01197769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotilingam D, Lev DC, Lazar AJ, Pollock RE. Staging soft tissue sarcoma: evolution and change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:282–291. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusuzaki K, Aomori K, Suginoshita T, Minami G, Takeshita H, Murata H, Hashiguchi S, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Total tumor cell elimination with minimum damage to normal tissues in musculoskeletal sarcomas following photodynamic therapy with acridine orange. Oncology. 2000;59:174–180. doi: 10.1159/000012156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusuzaki K, Minami G, Takeshita H, Murata H, Hashiguchi S, Nozaki T, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Photodynamic inactivation with acridine orange on a multidrug-resistant mouse osteosarcoma cell line. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:439–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Matsubara T, Miyazaki S, Okamura A, Seto M, Matsumine A, Hosoi H, Sugimoto T, Uchida A. Clinical trial of photodynamic therapy using acridine orange with/without low dose radiation as new limb salvage modality in musculoskeletal sarcomas. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1225–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Matsubara T, Miyazaki S, Shintani K, Seto M, Matsumine A, Hosoi H, Sugimoto T, Uchida A. Clinical outcome of a novel photodynamic therapy technique using acridine orange for synovial sarcomas. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:705–709. doi: 10.1562/2004-06-27-RA-218.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Matsubara T, Satonaka H, Wakabayashi T, Matsumine A, Uchida A. Acridine orange could be an innovative anticancer agent under photon energy. In Vivo. 2007;21:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Takeshita H, Hashiguchi S, Nozaki T, Emoto K, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Intracellular binding sites of acridine orange in living osteosarcoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusuzaki K, Suginoshita T, Minami G, Aomori K, Takeshita H, Murata H, Hashiguchi S, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Fluorovisualization effect of acridine orange on mouse osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:3019–3024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusuzaki K, Takeshita H, Murata H, Gebhardt MC, Springfield DS, Mankin HJ, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Polyploidization induced by acridine orange in mouse osteosarcoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:965–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam S, Kostashuk EC, Coy EP, Laukkanen E, LeRiche JC, Mueller HA, Szasz IJ. A randomized comparative study of the safety and efficacy of photodynamic therapy using Photofrin II combined with palliative radiotherapy versus palliative radiotherapy alone in patients with inoperable obstructive non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma. Photochem Photobiol. 1987;46:893–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandard AM, Petiot JF, Marnay J, Mandard JC, Chasle J, de Ranieri E, Dupin P, Herlin P, de Ranieri J, Tanguy A, et al. Prognostic factors in soft tissue sarcomas. A multivariate analysis of 109 cases. Cancer. 1989;63:1437–1451. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890401)63:7<1437::AID-CNCR2820630735>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsubara T, Kusuzaki K, Matsumine A, Murata H, Marunaka Y, Hosogi S, Uchida A, Sudo A. Photodynamic therapy with acridine orange in musculoskeletal sarcomas. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:760–762. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B6.23788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsubara T, Kusuzaki K, Matsumine A, Murata H, Nakamura T, Uchida A, Sudo A. Clinical outcomes of minimally invasive surgery using acridine orange for musculoskeletal sarcomas around the forearm, compared with conventional limb salvage surgery after wide resection. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:271–275. doi: 10.1002/jso.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsubara T, Kusuzaki K, Matsumine A, Murata H, Satonaka H, Shintani K, Nakamura T, Hosoi H, Iehara T, Sugimoto T, Uchida A. A new therapeutic modality involving acridine orange excitation by photon energy used during reduction surgery for rhabdomyosarcomas. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:89–94. doi: 10.3892/or_00000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsubara T, Kusuzaki K, Matsumine A, Shintani K, Satonaka H, Uchida A. Acridine orange used for photodynamic therapy accumulates in malignant musculoskeletal tumors depending on pH gradient. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monk BJ, Brewer C, VanNostrand K, Berns MW, McCullough JL, Tadir Y, Manetta A. Photodynamic therapy using topically applied dihematoporphyrin ether in the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:70–75. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muramatsu K, Ihara K, Miyoshi T, Yoshida K, Taguchi T. Clinical outcome of limb-salvage surgery after wide resection of sarcoma and femoral vessel reconstruction. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;25:1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura T, Kusuzaki K, Matsubara T, Matsumine A, Murata H, Uchida A. A new limb salvage surgery in cases of high-grade soft tissue sarcoma using photodynamic surgery, followed by photo- and radiodynamic therapy with acridine orange. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:523–528. doi: 10.1002/jso.21025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons HM, Habermann EB, Tuttle TM, Al-Refaie WB. Conditional survival of extremity soft-tissue sarcoma: results beyond the staging system. Cancer. 2011;117:1055–1060. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peabody TD, Gibbs CP, Jr, Simon MA. Evaluation and staging of musculoskeletal neoplasms. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1204–1218. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pisters PW, Harrison LB, Leung DH, Woodruff JM, Casper ES, Brennan MF. Long-term results of a prospective randomized trial of adjuvant brachytherapy in soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:859–868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pisters PW, Leung DH, Woodruff J, Shi W, Brennan MF. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1, 041 patients with localized soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1679–1689. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singer S, Demetri GD, Baldini EH, Fletcher CD. Management of soft-tissue sarcomas: an overview and update. Lancet Oncol. 2000;1:75–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sternberg ED, Dolphin D. Second generation photodynamic agents: a review. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1993;11:233–241. doi: 10.1089/clm.1993.11.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stinson SF, DeLaney TF, Greenberg J, Yang JC, Lampert MH, Hicks JE, Venzon D, White DE, Rosenberg SA, Glatstein EJ. Acute and long-term effects on limb function of combined modality limb sparing therapy for extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:1493–1499. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90324-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The JOA. Committee of Tumors. General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Studies on Malignant Bone Tumors [in Japanese] 3. Tokyo: Kanehara shuppan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trovik CS, Bauer HC, Alvegard TA, Anderson H, Blomqvist C, Berlin O, Gustafson P, Saeter G, Walloe A. Surgical margins, local recurrence and metastasis in soft tissue sarcomas: 559 surgically-treated patients from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Register. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:710–716. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukushi S, Nishida Y, Sugiura H, Nakashima H, Ishiguro N. Results of limb-salvage surgery with vascular reconstruction for soft tissue sarcoma in the lower extremity: comparison between only arterial and arteriovenous reconstruction. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:216–220. doi: 10.1002/jso.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Gao M, Wen S, Wang M. Photodynamic therapy for 50 patients with skin cancers or precancerous lesions. Chin Med Sci J. 1991;6:163–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO, USA: Mosby; 2008:15–31.

- 45.Yamada Y, Nishida Y, Nakashima H, Sugiura H, Tsukushi S, Kamei Y, Toriyama K, Ishiguro N. Oncologic and functional outcomes of soft tissue sarcomas of the distal upper extremity: comparison with those of the proximal upper extremity. Int Surg. 2010;95:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang JC, Chang AE, Baker AR, Sindelar WF, Danforth DN, Topalian SL, DeLaney T, Glatstein E, Steinberg SM, Merino MJ, Rosenberg SA. Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:197–203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida K, Kusuzaki K, Matsubara T, Matsumine A, Kumamoto T, Komada Y, Naka N, Uchida A. Periosteal Ewing’s sarcoma treated by photodynamic therapy with acridine orange. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PW, Pollock RE, Patel SR, Benjamin RS, Evans HL. Prognostic factors for patients with localized soft-tissue sarcoma treated with conservation surgery and radiation therapy: an analysis of 1225 patients. Cancer. 2003;97:2530–2543. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]