Abstract

Purpose

To identify risk factors associated with central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) among a diverse group of patients throughout the United States

Design

Longitudinal cohort study

Participants

All beneficiaries age ≥ 55 years who were continuously enrolled in a managed care network for at least ≥2 years and who had 2 visits to an eye care provider from 2001–2009

Methods

Insurance billing codes were used to identify individuals with a newly-diagnosed CRVO. Multivariable Cox regression was performed to determine factors associated with CRVO development.

Main Outcome Measure

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of being diagnosed with CRVO

Results

Of the 494,165 enrollees who met the study inclusion criteria, 1,302 (0.26%) were diagnosed with CRVO over 5.4 (±1.8) years. After adjustment for known confounders, blacks had a 57% increased risk of CRVO compared with whites (HR = 1.57 [95% CI: 1.25–1.98]) and females had a 24% decreased risk of CRVO compared with males (HR = 0.76 [95% CI: 0.67–0.85]). A diagnosis of stroke increased the hazard of CRVO by 45% (HR = 1.45 [95% CI: 1.24–1.70]) and hypercoagulable state was associated with a 146% increased CRVO risk (HR = 2.46 [95% CI: 1.41–4.29]). Individuals with end-organ damage from hypertension (HTN) or diabetes mellitus (DM) had a 90% (HR = 1.90 [95% CI: 1.50–2.41]) and 53% (HR = 1.53 [95% CI: 1.28–1.84]) increased risk of CRVO, respectively, relative to those without these conditions.

Conclusion

This study confirms that HTN and vascular diseases are important risk factors for CRVO. We also identify black race as a predictor of CRVO that was not well-appreciated previously. Furthermore, we show that compared to patients without DM, individuals with end-organ damage from DM (i.e., “complicated” cases) have a heightened risk of CRVO, while those with uncomplicated DM are not at increased risk of CRVO. This finding may provide a potential explanation for the conflicting reports in the literature on the association between CRVO and DM. Information from analyses like this can be used to create a risk calculator to identify individuals at greatest risk for CRVO.

Introduction

Among the retinal vascular diseases, retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is one of the most common causes of visual loss, second only to diabetic retinopathy.1 A recent analysis by Rogers and colleagues revealed that approximately 16.4 million adults worldwide are affected by RVO.2 Of these, 2.5 million adults suffer from central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO).2 This number will undoubtedly continue to increase as the population ages, since older patients are at increased risk for CRVO compared to their younger counterparts.1 Although fewer people are affected by CRVO compared with branch retinal vein occlusions (BRVO), CRVO is associated with a worse visual prognosis. In one study of patients with macular edema from BRVO who presented with visual acuity levels of 20/40 or worse, only 23% had a final visual acuity of 20/200 or worse three years later.3 In contrast, another study found that 54% of patients with CRVO who presented with worse than 20/40 vision had a final visual acuity worse than 20/200 after three years.4 Additionally, CRVO more frequently leads to neovascularization of the iris or anterior chamber angle, which can result in devastating complications such as neovascular glaucoma.5

Despite the emergence of ranibizumab as a potential therapy for macular edema associated with CRVO,6 the overall visual prognosis associated with CRVO remains guarded. In one study, nearly two thirds of all CRVO patients treated with ranibizumab had a visual acuity of < 20/40 after 6 months.6 Thus, there are many reasons to look towards primary prevention strategies to reduce the morbidity associated with CRVO. Identifying individuals at greatest risk for CRVO and treating modifiable risk factors can help prevent patients from developing this sight-threatening condition.

While hypertension (HTN)7–16 and glaucoma8,12,13,17,18 are often cited as risk factors for CRVO, the relationship between other medical conditions and CRVO is more nebulous (Table 1, available at http://aaojournal.org).7–15,17–36 Some studies have shown diabetes mellitus (DM)9,10,12,31 and hyperlipidemia (HLD)11,35,36 to be important predictors of CRVO, but other investigators were unable to find a significant association between either DM8,13,37 or HLD18,37 and CRVO. Likewise, the role of hypercoagulable states in causing CRVO is not clearly defined. While several small studies have failed to show an association between CRVO and Factor V Leiden gene mutation,22,23,25 a recent meta-analysis revealed a small but significant relationship between this mutation and RVO.38 Similarly, even though hyper-homocysteinemia is gaining favor as a risk factor for CRVO,11,23–25,35 two studies have called the relationship between elevated homocysteine and RVOs into question.39,40

Table 1.

Published studies on risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion

| STUDY | SAMPLE SIZE | KEY FINDINGS/CONCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Luntz et al. 198019 | - |

|

| Appiah et al. 198920 | 145 CRVO patients 214 BRVO patients |

|

| Elman et al. 19907 | 197 CRVO patients |

|

| Rath et al. 19928 | 87 RVO patients |

|

| The Eye Disease Case Control Study Group 19969 | 258 CRVO patients |

|

| Mitchell et al. 199621 | 41 BRVO patients 3 HRVO patients 15 CRVO patients |

|

| Hirota et al. 199717 | 18 RVO patients (9 CRVO) |

|

| Sperduto et al. 199810 | 79 HRVO patients 258 CRVO patients 270 BRVO patients |

|

| Kalayci et al. 199922 | 25 HRVO/CRVO patients 27 BRVO patients |

|

| Hayreh et al. 200115 | 1090 RVO patients placed into CRVO, HRVO, and BRVO categories |

|

| Marcucci et al. 200111 | 100 CRVO patients |

|

| Adamczuk et al. 200223 | 37 CRVO patients |

|

| Fegan 200224 | - |

|

| Lahey et al. 200225 | 55 CRVO patients (< 56 y/o) |

|

| Prisco et al. 200226 | - |

|

| Lahey et al. 200327 | - |

|

| Shahsuvaryan et al. 200312 | 408 CRVO patients |

|

| Gao et al. 200628 | 64 CRVO patients |

|

| Gumus et al. 200613 | 56 CRVO patients 26 BRVO patients |

|

| Koizumi et al. 200718 | 144 CRVO patients |

|

| Narayanasamy et al. 200729 | 29 CRVO patients 57 Controls |

|

| Glueck et al. 200830 | 40 CRVO patients |

|

| Klein et al. 200831 | 64 BRVO patients 19 CRVO patients |

|

| Moghimi et al. 200832 | 54 CRVO patients |

|

| Sodi et al. 200833 | 17 recurrent CRVO patients 30 single episode CRVO patients |

|

| Thapa et al. 200934 | 2 CRVO patients |

|

| Kuo et al. 201035 | 22 CRVO patients (< 40 y/o) |

|

| Maier et al. 201114 | 315 CRVO patients |

|

| Sodi et al. 201136 | 41 Ischemic CRVO patients 62 Non-Ischemic CRVO patients |

|

Abbreviations: CRVO, Central Retinal Vein Occlusion; RF, Risk Factor; BRVO, Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion; HTN, Hypertension; ESR, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; IOP, Intraocular Pressure; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; OAG, Open-Angle Glaucoma; CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; CVA, Cerebrovascular Accident; RVO, Retinal Vein Occlusion; PT, Prothrombin; HRVO, Hemiretinal Vein Occlusion; PVD, Peripheral Vascular Disease; GI, Gastrointestinal; PAI, Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor; Ab, Antibody; MTHFR, Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase; APC, Activated Protein C; ACE, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; FVL, Factor V Leiden; AT, Antithrombin;

Given the controversy surrounding some of the presumed risk factors for CRVO, further studies are needed confirm existing risk factors and identify new ones that may be associated with CRVO. These studies will ideally involve large numbers of patients with CRVO, as many of the prior investigations into risk factors for CRVO were limited by small sample sizes or did not adequately account for potential confounding factors. In the present analysis, we used data from a large nationwide sample of enrollees in a managed care network to identify and help clarify risk factors associated with CRVO. Information from this and other studies may be used to create a risk calculator for CRVO, similar to a recently developed tool that assesses an individual’s risk of developing advanced AMD.41 Such a risk calculator could serve as a useful means of educating patients about CRVO and motivating them toward healthy behaviors.

Methods

Data Source

The i3 InVision Data Mart database (Ingenix, Eden Prairie, MN) contains detailed records of all beneficiaries in a managed care network throughout the United States. Enrollees came from all 48 continental states and were relatively well distributed. The dataset contains all individuals with one or more International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for eye-related diagnoses (360–379.9), one or more Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for any eye-related visits, diagnostic, or therapeutic procedures (65091–68899 or 92002–92499), or any other claim submitted by an ophthalmologist or optometrist from January 1, 2001 through December 31, 2009. For each enrollee, we had access to all medical claims for ocular and non-ocular conditions and sociodemographic information including age, sex, race, education level and household net worth. Additionally, the database has records of all outpatient prescriptions since enrollees in the medical plan were also fully enrolled in the pharmacy plan.

Participants and Sample Selection

Individuals were included in the analysis if they met the following criteria: continuous enrollment in the medical plan for at least two years, two or more visits to an eye care provider (ophthalmologist or optometrist) and age ≥ 55 years. We decided to use a cut-off age of 55 because another large population-based study failed to detect any incident CRVOs in those less than 55 years old.42 Individuals were excluded if they received a diagnosis of CRVO during the first two years they were enrolled in the plan, in order to exclude non-incident cases. To be counted as an incident case of CRVO, individuals must have had at least one eye care visit during their first two years in the plan (with no documented diagnosis of CRVO) and then must have been diagnosed with CRVO at a subsequent visit after the index date (two years after entry into the plan). Beneficiaries were identified with a CRVO if they had one or more billing records with the ICD-9-CM code 362.35. Individuals diagnosed with BRVO (ICD-9-CM code 362.36) or RVO unspecified (ICD-9-CM code 362.30) were not classified as experiencing a CRVO.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Participant characteristics were summarized for the entire sample using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Cox regression with delayed entry was used to estimate the hazard of being diagnosed with a CRVO. All beneficiaries were followed in the model from the index date until they were either diagnosed with CRVO or were censored. Censoring occurred at the date of their last eye examination, as this was conceivably their last opportunity to receive a diagnosis of CRVO by an eye care provider. Initially, single-variable models were run to test potential predictors individually. Multivariable models were adjusted for age (the time axis), sex, race, education level, household net worth, region of residence at the time of medical plan enrollment, the following ocular comorbidities (cataract, pseudophakia or aphakia, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), open-angle glaucoma, exfoliation syndrome, and ocular hypertension) and the following medical comorbidities (DM, HTN, HLD, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), myocardial infarction (MI), peripheral artery disease (PAD), congestive heart failure, depression, dementia, sleep apnea syndrome, cancer, hypercoagulable state, use of anticoagulants, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), and the Charlson comorbidity index (a measure of overall health)) (Table 2, available at http://aaojournal.org). In this analysis, CVA, MI, DVT/PE, and use of anticoagulants were treated as time-dependent covariates since we wanted to delineate the temporal relationship between the exposure and the outcome of interest (CRVO). Open-angle glaucoma and exfoliation syndrome were included in the models because these conditions have previously been shown to be associated with CRVO.8,43

Table 2.

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification Codes

| Condition | ICD-9-CM Codes |

|---|---|

| Age-related Macular Degeneration | 362.50, 362.51, 362.52, 362.57 |

| Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion | 362.36 |

| Cancer | 140,140.0, 140.1, 140.3, 140.4, 140.5, 140.6, 140.8, 140.9, 141, 141.0, 141.1, 141.2, 141.3, 141.4, 141.5, 141.6, 141.8, 141.9, 142, 142.0, 142.1, 142.2, 142.8, 142.9, 143, 143.0, 143.1, 143.8, 143.9, 144, 144.0, 144.1, 144.8, 144.9, 145, 145.0, 145.1, 145.2, 145.3, 145.4, 145.5, 145.6, 145.8, 145.9, 146, 146.0, 146.1, 146.2, 146.3, 146.4, 146.5, 146.6, 146.7, 146.8, 146.9, 147, 147.0, 147.1, 147.2, 147.3, 147.8, 147.9, 148, 148.0, 148.1, 148.2, 148.3, 148.8, 148.9, 149, 149.0, 149.1, 149.8, 149.9, 150, 150.0, 150.1, 150.2, 150.3, 150.4, 150.5, 150.8, 150.9, 151,151.0, 151.1, 151.2, 151.3, 151.4, 151.5, 151.6, 151.8, 151.9, 152, 152.0, 152.1, 152.2, 152.3, 152.8, 152.9, 153, 153.0, 153.1, 153.2, 153.3, 153.4, 153.5, 153.6, 153.7, 153.8, 153.9, 154, 154.0, 154.1, 154.2, 154.3, 154.8, 155, 155.0, 155.1, 155.2, 156, 156.0, 156.1, 156.2, 156.8, 156.9, 157, 157.0, 157.1, 157.2, 157.3, 157.4, 157.8, 157.9, 158, 158.0, 158.8, 158.9, 159, 159.0, 159.1, 159.8, 159.9, 160, 160.0, 160.1, 160.2, 160.3, 160.4, 160.5, 160.8, 160.9, 161, 161.0, 161.1, 161.2, 161.3, 161.8, 161.9, 162,162.0, 162.2, 162.3, 162.4, 162.5, 162.8, 162.9, 163, 163.0, 163.1, 163.8, 163.9, 164, 164.0, 164.1, 164.2, 164.3, 164.8, 164.9, 165, 165.0, 165.8, 165.9, 170, 170.0, 170.1, 170.2, 170.3, 170.4, 170.5, 170.6, 170.7, 170.8, 170.9, 171, 171.0, 171.2, 171.3, 171.4, 171.5, 171.6, 171.7, 171.8, 171.9, 172, 172.0, 172.1, 172.2, 172.3, 172.4, 172.5, 172.6, 172.7, 172.8, 172.9, 174, 174.0, 174.1, 174.2, 174.3, 174.4, 174.5, 174.6, 174.8, 174.9, 175, 175.0, 175.9, 176, 176.0, 176.1, 176.2, 176.3, 176.4, 176.5, 176.8, 176.9, 179, 180, 180.0, 180.1, 180.8, 180.9, 181, 182, 182.0, 182.1, 182.8, 183, 183.0, 183.2, 183.3, 183.4, 183.5, 183.8, 183.9, 184, 184.0, 184.1, 184.2, 184.3, 184.4, 184.8, 184.9, 185, 186, 186.0, 186.9, 187, 187.1, 187.2, 187.3, 187.4, 187.5, 187.6, 187.7, 187.8, 187.9, 188, 188.0, 188.1, 188.2, 188.3, 188.4, 188.5, 188.6, 188.7, 188.8, 188.9, 189, 189.0, 189.1, 189.2, 189.3, 189.4, 189.8, 189.9, 190, 190.0, 190.1, 190.2, 190.3, 190.4, 190.5, 190.6, 190.7, 190.8, 190.9, 191,191.0, 191.1, 191.2, 191.3, 191.4, 191.5, 191.6, 191.7, 191.8, 191.9, 192, 192.0, 192.1, 192.2, 192.3, 192.8, 192.9, 193, 194, 194.0, 194.1, 194.3, 194.4, 194.5, 194.6, 194.8, 194.9, 195, 195.0, 195.1, 195.2, 195.3, 195.4, 195.5, 195.8, 200, 200.0, 200.1, 200.2, 200.8, 201, 201.0, 201.1, 201.2, 201.4, 201.5, 201.6, 201.7, 201.9, 202, 202.0, 202.1, 202.2, 202.3, 202.4, 202.5, 202.6, 202.8, 202.9, 203, 203.0, 203.00, 203.01, 203.1, 203.10, 203.11, 204, 204.0, 204.00, 204.01, 204.1, 204.10, 204.11, 204.2, 204.20, 204.21, 204.8, 204.80, 204.81, 204.9, 204.90, 204.91, 205, 205.0, 205.00, 205.01, 205.1, 205.10, 205.11, 205.2, 205.20, 205.21, 205.3, 205.30, 205.31, 205.8, 205.80, 205.81, 205.9, 205.90, 205.91, 206, 206.0, 206.00, 206.01, 206.1, 206.10, 206.11, 206.2, 206.20, 206.21, 206.8, 206.80, 206.81, 207, 207.0, 207.00, 207.01, 207.1, 207.10, 207.11, 207.2, 207.20, 207.21, 207.8, 207.80, 207.81, 208, 208.0, 208.00, 208.01, 220.81, 208.10, 208.11, 208.2, 208.20, 208.21, 208.8, 208.80, 208.81, 208.9, 208.90, 208.91, 238.6 |

| Cataract | 366, 366.0, 366.00, 366.01, 366.02, 366.03, 366.04, 366.09, 366.1, 366.10, 366.12, 366.13, 366.14, 366.15, 366.16, 366.17, 366.18, 366.19, 366.41, 366.45 |

| Central Retinal Vein Occlusion | 362.35 |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | 362.34, 430, 431, 432, 432.0, 432.1, 432.9, 433, 433.0, 433.1, 433.2, 433.3, 433.8, 433.9, 434, 434.0, 434.00, 434.01, 434.1, 434.10, 434.11, 434.9, 434.90, 434.91, 435, 435.0, 435.1, 435.2, 435.3, 435.8, 435.9, 436, 437, 437.0, 437.1, 437.2, 437.3, 437.4, 437.5, 437.6, 437.7, 437.8, 437.9, 438, 438.0, 438.1, 438.10, 438.11, 438.12, 438.19, 438.2, 438.20, 438.21, 438.22, 438.3, 438.30, 438.31, 438.32, 438.4, 438.40, 438.41, 438.42, 438.5, 438.50, 438.51, 438.52, 438.53, 438.6, 438.7, 438.8, 438.81, 438.82, 438.83, 438.84, 438.85, 438.89, 438.9 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 425.4, 425.5, 425.7, 425.8, 425.9, 428, 428.0, 428.1, 428.2, 428.20, 428.21, 428.22, 428.23, 428.3, 428.30, 428.31, 428.32, 428.33, 428.4, 428.40, 428.41, 428.42, 428.43, 428.9 |

| Deep Venous Thrombosis or Pulmonary Embolism | 415.19, 453.40, 453.41, 453.42 |

| Dementia | 290, 290.0, 290.1, 290.10, 290.11, 290.12, 290.13, 290.2, 290.20, 290.21, 290.3, 290.4, 290.40, 290.41, 290.42, 290.43, 290.8, 290.9, 294.1, 294.10, 294.11, 331.2 |

| Depression | 296, 296.0, 296.00, 296.01, 296.02, 296.03, 296.04, 296.05, 296.06, 296.1, 296.10, 296.11, 296.12, 296.13, 296.14, 296.15, 296.16, 296.2, 296.20, 296.21, 296.22, 296.23, 296.24, 296.25, 296.26, 296.3, 296.30, 296.31, 296.32, 296.33, 296.34, 296.35, 296.36, 296.4, 296.40, 296.41, 296.42, 296.43, 296.44, 296.45, 296.46, 296.5, 296.50, 296.51, 296.52, 296.53, 296.54, 296.55, 296.56, 296.6, 296.60, 296.61, 296.62, 296.63, 296.64, 296.65, 296.66, 296.7, 296.70, 296.71, 296.72, 296.73, 296.74, 296.75, 296.76, 296.8, 296.80, 296.81, 296.82, 296.89, 296.9, 296.90, 296.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250.0, 250.00, 250.01, 250.02, 250.03, 250.1, 250.10, 250.11, 250.12, 250.13, 250.2, 250.20, 250.21, 250.22, 250.23, 250.3, 250.30, 250.31, 250.32, 250.33, 250.4, 250.40, 250.41, 250.42, 250.43, 250.5, 250.50, 250.51, 250.52, 250.53, 250.5, 250.50, 250.51, 250.52, 250.53, 250.6, 250.60, 250.61, 250.62, 250.63, 250.7, 250.70, 250.71, 250.72, 250.73, 250.8, 250.80, 250.81, 250.82, 250.83, 250.9, 250.90, 250.91, 250.92, 250.93, 362.01, 362.92, 362.03, 362.04, 362.05, 362.06, 362.07 |

| Uncomplicated Diabetes Mellitus | 250.3, 250.30, 250.31, 250.32, 250.33, 250.8, 250.80, 250.81, 250.82, 250.83, 250.9, 250.90, 250.91, 250.92, 250.93, 250.0, 250.00, 250.01, 250.02, 250.03, 250.1, 250.10, 250.11, 250.12, 250.13, 250.2, 250.20, 250.21, 250.22, 250.23 |

| Complicated Diabetes Mellitus | 250.4, 250.40, 250.41, 250.42, 250.43, 250.5, 250.50, 250.51, 250.52, 250.53, 250.6, 250.60, 250.61, 250.62, 250.63, 250.7, 250.70, 250.71, 250.72, 250.73, 362.01, 362.02, 362.03, 362.04, 362.05, 362.06, 362.07 |

| Hypercoagulable State | 289.81, 289.82 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 272, 272.0, 272.1, 272.2, 272.3, 272.4, 272.5, 272.6, 272.7, 272.8, 272.9 |

| Hypertension | 401, 401.0, 401.1, 401.9, 405, 405.0, 405.1, 405.01, 405.09, 405.11, 405.19, 405.9, 405.91, 405.99, 362.11, 402, 402.0, 402.00, 402.01, 402.1, 402.10, 402.11, 402.9, 402.90, 402.91, 403, 403.0, 403.00, 403.01, 403.1, 403.10, 403.11, 403.9, 403.90, 403.91, 404.0, 404.00, 404.01, 404.02, 404.03, 404.1, 404.10, 404.11, 404.12, 404.13, 404.9, 404.90, 404.91, 404.92, 404.93 |

| Uncomplicated Hypertension | 401, 401.0, 401.1, 401.9, 405, 405.0, 405.1, 405.01, 405.09, 405.11, 405.19, 405.9, 405.91, 405.99 |

| Complicated Hypertension | 362.11, 402, 402.0, 402.00, 402.01, 402.1, 402.10, 402.11, 402.9, 402.90, 402.91, 403, 403.0, 403.00, 403.01, 403.1, 403.10, 403.11, 403.9, 403.90, 403.91, 404.0, 404.00, 404.01, 404.02, 404.03, 404.1, 404.10, 404.11, 404.12, 404.13, 404.9, 404.90, 404.91, 404.92, 404.93 |

| Kidney Disease | 250.4, 250.40, 250.41, 250.42, 250.43, 582, 582.0, 582.1, 582.2, 582.4, 582.8, 582.81, 582.89, 582.9, 583, 583.0, 583.1, 583.2, 583.4, 583.6, 583.7, 583.8, 583.81, 583.89, 583.9, 585, 585.1, 585.2, 585.3, 585.4, 585.5, 585.6, 585.9, 586, 587, 403, 403.0, 403.00, 403.01, 403.11, 403.91, 403.10, 403.90, 403.1, 403.9, 404, 404.0, 404.1, 404.9, 404.00, 404.10, 404.90, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 404.02, 404.12, 404.92, 404.03, 404.13, 404.93 or CPT codes 90935, 90937 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 410, 410.0, 410.00, 410.01, 410.02, 410.1, 410.10, 410.11, 410.12, 410.2, 410.20, 410.21, 410.22, 410.3, 410.30, 410.31, 410.32, 410.4, 410.40, 410.41, 410.42, 410.5, 410.50, 410.51, 410.52, 410.6, 410.60, 410.61, 410.62, 410.7, 410.70, 410.71, 410.72, 410.8, 410.80, 410.81, 410.82, 410.9, 410.90, 410.91, 410.92, 412 |

| Ocular Hypertension | 365.04 |

| Open-angle glaucoma | 365.1, 365.10, 365.11, 365.12, 365.15 |

| Retinal Vein Occlusion (unspecified) | 362.30 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 093.0, 437.3, 440, 440.0, 440.1, 440.2, 440.20, 440.21, 440.22, 440.23, 440.24, 440.29, 441, 441.0, 441.00, 441.01, 441.02, 441.03, 441.1, 441.2, 441.3, 441.4, 441.5, 441.6, 441.7, 441.9, 443.1, 443.2, 443.21, 443.22, 443.23, 443.24, 443.29, 443.8, 443.81, 443.82, 443.89, 443.9, 447.1, 557.1, 557.9, V43.4 |

| Exfoliation Syndrome | 366.11, 365.52 |

| Pseudophakia or aphakia | V43.1, 379.3, 379.31 |

| Sleep apnea syndrome | 327.2, 327.20, 327.21, 327.23, 327.27, 327.29, 780.51, 780.53, 780.57 |

Anticoagulants include: Marevin, Jantoven, Coumadin, Warfarin, Heparin, Clopidogrel, Ticlopidine, Plavix, Miradon, Dicumarol, Enoxaparin, Acenocoumarol, Anisinsione, Sintrom

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification

An additional Cox regression model was performed to assess whether the severity of DM and HTN affected the risk of being diagnosed with a CRVO after adjusting for the above-mentioned covariates. Individuals with DM and HTN were each stratified into two groups (those without end-organ damage from DM or HTN which we consider “uncomplicated” cases and those with end-organ damage (e.g., nephropathy) which we consider “complicated” cases) based on ICD-9-CM billing codes. For all analyses, p-values of ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

We also performed a sensitivity analysis to determine whether the associations between the main predictor variables and CRVO were affected if we changed our definition of CRVO from requiring at least one ICD-9-CM code for this condition to requiring at least two codes on separate dates. This was done to help address concerns about patients who may have been miscoded or misdiagnosed with a CRVO the first time they received this diagnosis.

Since all the data were de-identified, the University of Michigan determined that this study was exempt from requiring Institutional Review Board approval.

Results

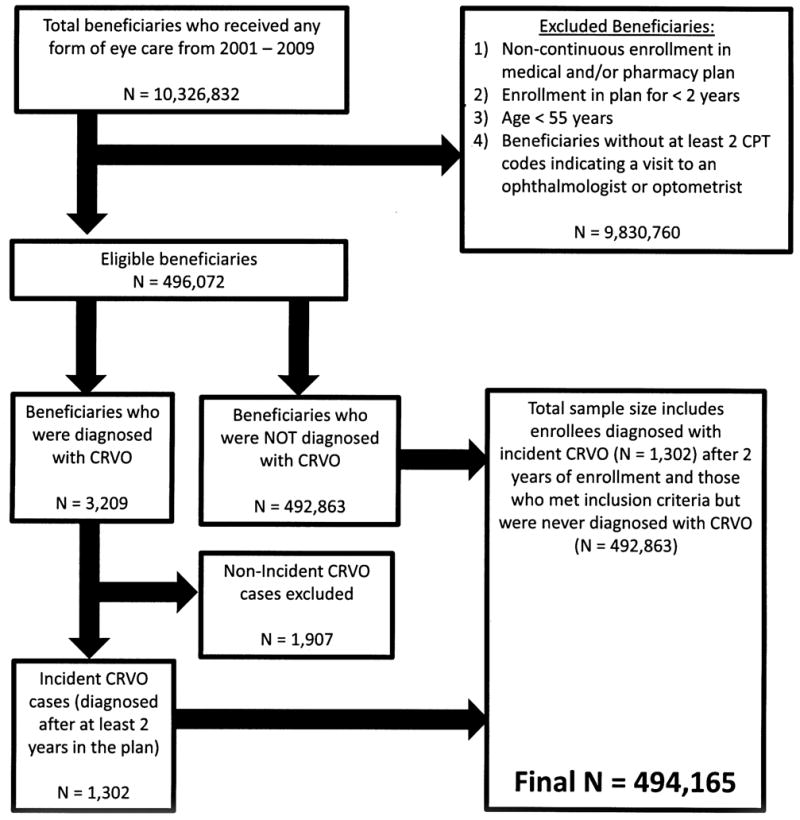

A total of 494,165 beneficiaries met the study inclusion criteria. (Figure 1) During the study period, there were 1,302 enrollees (0.26%) who were newly-diagnosed with a CRVO. Among those diagnosed with CRVO, 1,251 (96.1%) of the diagnoses were made by eye care providers (ophthalmologists or optometrists). The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age of the group identified as experiencing CRVO was 69.9 (8.4) years, and the mean age of the group not diagnosed with CRVO was 65.7 (8.1) years (p < 0.0001). The average time in the plan for the group of enrollees in whom CRVO was detected was 5.4 (1.8) years and for those in whom CRVO was not detected was 4.7 (1.7) years (p < 0.0001). Among the 1,302 enrollees who were classified as having CRVO, 667 (51.2%) were female, and the racial distribution included 1,017 whites (78.1%), 94 blacks (7.2%), 51 Latinos (3.9%), 13 Asians (1.0%), 7 enrollees of other races (0.54%), and 120 whose race was not documented (9.2%) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Selection of beneficiares of analysis

TABLE 3.

Patient Demographics

| Total sample | Enrollees Not Diagnosed with CRVO | Enrollees Diagnosed with CRVO | P-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Enrollees, n (%) | 494,165 (100) | 492,863 (99.7) | 1,302 (0.3) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 65.7 (8.1) | 69.9 (8.4) | p<0.0001 | |

| Years in Plan, mean (SD) | 4.7 (1.7) | 5.4 (1.8) | p<0.0001 | |

| Sex, n (%) | p<0.0001 | |||

| Male | 206,181 (41.7) | 205,546 (41.7) | 635 (48.8) | |

| Female | 287,984 (58.3) | 287,317 (58.3) | 667 (51.2) | |

| Race, n (%) | p=0.0006 | |||

| White | 394,001 (79.7) | 392,984 (79.7) | 1,017 (78.1) | |

| Black | 24,085 (4.9) | 23,991 (4.9) | 94 (7.2) | |

| Latino | 16,874 (3.4) | 16,823 (3.4) | 51 (3.9) | |

| Asian | 7,993 (1.6) | 7,980 (1.6) | 13 (1.0) | |

| Other | 3,314 (0.67) | 3,307 (0.67) | 7 (0.54) | |

| Unknown | 47,898 (9.7) | 47,778 (9.7) | 120 (9.2) | |

| Medical Condition, n (%) | ||||

| Metabolic Syndrome | 142,588 (28.9) | 142,101 (28.8) | 487 (37.4) | p<0.0001 |

| PAD | 95,635 (19.4) | 95,185 (19.3) | 450 (34.6) | p<0.0001 |

| CVA | 80,761 (16.3) | 80,312 (16.3) | 449 (34.5) | p<0.0001 |

| MI | 39,991 (8.1) | 39,847 (8.1) | 144 (11.1) | p<0.0001 |

| DVT/PE | 12,953 (2.6) | 12,901 (2.6) | 52 (4.0) | p=0.0019 |

| Hypercoagulable State | 1798 (0.36) | 1,783 (0.36) | 15 (1.2) | p<0.0001 |

| HTN | 377,299 (76.4) | 376,142 (76.3) | 1,157 (88.9) | p<0.0001 |

| HLD | 394,279 (79.8) | 393,191 (79.8) | 1,088 (83.6) | p=0.0007 |

| DM | 166,847 (33.8) | 166,289 (33.7) | 558 (42.9) | p<0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CRVO, Central Retinal Vein Occlusion; PAD, Peripheral Artery Disease; CVA, Cerebrovascular Accident; MI, Myocardial Infarction; DVT, Deep Venous Thrombosis; PE, Pulmonary Embolism; SD, Standard Deviation; HTN, Hypertension; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; HLD, Hyperlipidemia. “Metabolic Syndrome” refers to the combination of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.

P-values compare the unadjusted proportions of enrollees who were and were not diagnosed with CRVO.

The majority of beneficiaries who were diagnosed with CRVO had one or more components of metabolic syndrome, defined as the presence of coexisting DM, HTN, and HLD. Among those enrollees who were identified as having a CRVO, 487 patients (37.4%) had metabolic syndrome. By comparison, 142,101 individuals (28.8%) who were not diagnosed with CRVO had metabolic syndrome. Vascular diseases affecting the venous and arterial systems were also more common among individuals who were classified as experiencing CRVO as compared with others who were not. Among the enrollees in whom CRVO was detected, the proportions of people with a history of DVT / PE or hypercoagulable state were 4% and 1.2%, respectively. By comparison, the proportions of those in whom CRVO was not detected who had a DVT / PE or hypercoagulable state were 2.6% and 0.4%, respectively. Likewise, among the group identified as experiencing CRVO, the proportion who suffered from PAD, MI, or CVA were 34.6%, 11.1%, and 34.5%, respectively. In contrast, the proportions of patients without CRVO who had PAD, MI, or CVA were 19.3%, 8.1%, and 16.3%, respectively (Table 3).

Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis

Sociodemographic factors

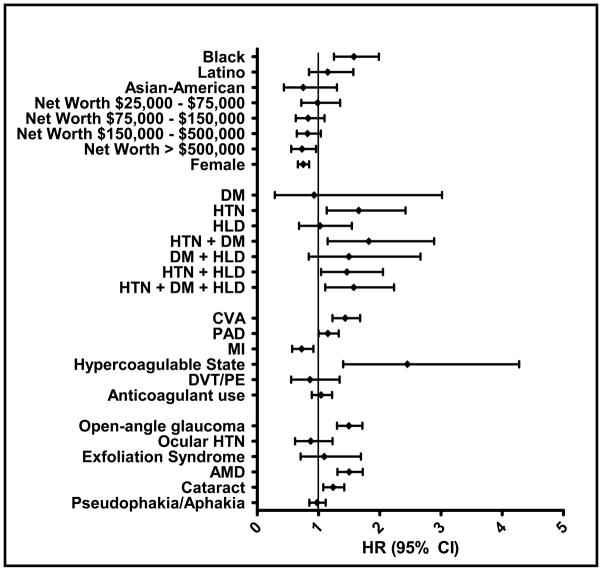

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, blacks had a 58% increased hazard of being diagnosed with CRVO compared with non-Hispanic whites (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 1.58 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.25–1.99]). There was no significant difference in the risk of being diagnosed with CRVO when comparing Latinos (HR = 1.15 [95% CI: 0.84–1.57]) and Asian Americans (HR = 0.75 [95% CI: 0.43–1.30]) with non-Hispanic whites. Females were 25% less likely than males to be identified as having a CRVO (HR = 0.75 [95% CI: 0.66–0.85]). Individuals with the highest levels of household net worth (≥$500,000) had a 27% decreased hazard of being diagnosed with CRVO compared to enrollees with the lowest net worth level (≤$25,000) (HR = 0.73 [95% CI: 0.56–0.96]). However, there was no significant difference in risk of CRVO between individuals with net worth levels between $25,000 and $500,000 and those with a household net worth ≤$25,000 (p>0.05 for all comparisons) (Table 4 and Figure 2).

TABLE 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Analyses of Factors Associated with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

| VARIABLE | Univariable Analysis HR (95% CI); p-value | Multivariable Analysis HR (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||

| White | ref | ref |

| Black | 1.90 (1.54–2.35); p<0.0001 | 1.58 (1.25–1.99); p<0.0001 |

| Latino | 1.34 (1.01–1.78); p=0.04 | 1.15 (0.84–1.57); p=0.37 |

| Asian-American | 0.71 (0.41–1.23); p=0.22 | 0.75 (0.43–1.30); p=0.31 |

| Net worth < $25,000 | ref | ref |

| Net worth $25,000–$75,000 | 0.97 (0.72–1.31); p=0.84 | 0.99 (0.72–1.35); p=0.94 |

| Net worth $75,000–$150,000 | 0.79 (0.61–1.03); p=0.08 | 0.83 (0.63–1.10); p=0.19 |

| Net worth $150,000–$500,000 | 0.75 (0.60–0.94); p=0.01 | 0.82 (0.65–1.04); p=0.10 |

| Net worth > $500,000 | 0.63 (0.50–0.80); p=0.0001 | 0.73 (0.56–0.96); p=0.02 |

| Male | ref | ref |

| Female | 0.77 (0.69–0.86); p<0.0001 | 0.75 (0.66–0.85); p<0.0001 |

| Metabolic Syndrome Components | ||

| No DM, HTN, or HLD | ref | ref |

| DM | 1.14 (0.41–3.17); p=0.80 | 0.93 (0.29–3.02); p=0.90 |

| HTN | 1.61 (1.14–2.26); p=0.006 | 1.66 (1.14–2.42); p=0.01 |

| HLD | 0.98 (0.68–1.41); p=0.91 | 1.03 (0.68–1.54); p=0.90 |

| HTN+DM | 2.34 (1.56–3.51); p<0.0001 | 1.82 (1.15–2.89); p=0.01 |

| DM+HLD | 1.66 (0.98–2.80); p=0.06 | 1.50 (0.84–2.67); p=0.17 |

| HTN+HLD | 1.57 (1.16–2.12); p=0.003 | 1.46 (1.04–2.05); p=0.03 |

| HTN+DM+HLD | 2.00 (1.48–2.69); p<0.0001 | 1.58 (1.11–2.23); p=0.01 |

| Vascular Disease | ||

| CVA | 1.66 (1.45–1.90); p<0.0001 | 1.44 (1.23–1.68); p<0.0001 |

| PAD | 1.40 (1.24–1.57); p<0.0001 | 1.15 (1.00–1.33); p=0.05 |

| MI | 0.93 (0.75–1.15); p=0.50 | 0.72 (0.57–0.92); p=0.01 |

| Hypercoagulable State | 2.78 (1.67–4.62); p<0.0001 | 2.45 (1.40–4.28); p=0.002 |

| DVT or PE | 1.03 (0.68–1.55); p=0.89 | 0.86 (0.55–1.34); p=0.51 |

| Anticoagulant use | 1.25 (1.10–1.43); p=0.0009 | 1.04 (0.89–1.22); p=0.60 |

| Ophthalmic | ||

| Open-angle glaucoma | 1.57 (1.38–1.78); p<0.0001 | 1.50 (1.30–1.72); p<0.0001 |

| Ocular hypertension | 0.90 (0.66–1.23); p=0.52 | 0.87 (0.62–1.23); p=0.44 |

| Exfoliation Syndrome | 1.08 (0.73–1.60); p=0.69 | 1.09 (0.71–1.69); p=0.69 |

| AMD | 1.46 (1.28–1.65); p<0.0001 | 1.50 (1.31–1.72); p<0.0001 |

| Cataract | 1.22 (1.07–1.38); p=0.003 | 1.24 (1.08–1.42); p=0.003 |

| Pseudophakia/Aphakia | 1.09 (0.96–1.24); p=0.17 | 0.98 (0.85–1.12); p=0.72 |

Abbreviations: HR, adjusted Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; CRVO, Central Retinal Vein Occlusion; ref, reference group; AMD, Age-related Macular Degeneration; HTN, hypertension; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; HLD, Hyperlipidemia; CVA, Cerebrovascular Accident; PAD, Peripheral Artery Disease; MI, Myocardial Infarction; DVT, Deep Venous Thrombosis; PE, Pulmonary Embolism. Statistically significant results (p≤0.05) are bolded. For all medical conditions listed, comparisons were made to individuals without these conditions.

Figure 2.

Multivariable Cox Regression

Components of Metabolic Syndrome and CRVO

In the regression model, we assessed the relationship between components of metabolic syndrome (HTN, DM, and HLD) individually and in different combinations with the risk of being diagnosed with CRVO. Individuals with HTN alone (no DM or HLD) had a 66% increased hazard of being identified as having CRVO (HR = 1.66 [95% CI: 1.14–2.42]) relative to those without HTN, DM, or HLD. Persons with DM alone (no HTN or HLD) or HLD alone (no DM or HTN) did not exhibit an increased hazard of CRVO relative to those without these conditions (p>0.05 for both comparisons). Individuals with all three metabolic syndrome components had a 58% increased hazard of CRVO (HR = 1.58 [95% CI: 1.11–2.23]) relative to those with none of these conditions (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Vascular Disease and CRVO

In the regression model, several vascular conditions increased the risk of CRVO. Enrollees with a prior stroke had a 44% increased hazard of being diagnosed with CRVO (HR = 1.44 [95% CI: 1.23–1.68]). Those with PAD had a 15% increased hazard of CRVO (HR = 1.15 [95% CI: 1.00–1.33]). Those with a primary or secondary hypercoagulable state had a 145% increased hazard of CRVO (HR = 2.45 [95% CI: 1.40–4.28]). However, individuals with a history of a DVT or PE did not have an increased risk of CRVO (HR = 0.86 [95% CI: 0.55–1.34]) and enrollees with a prior MI actually had a decreased hazard of being diagnosed with CRVO (HR = 0.72 [95% CI: 0.57–0.92]). There was no association between use of anticoagulants such as warfarin and risk of CRVO (p = 0.60) (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Severity of Disease

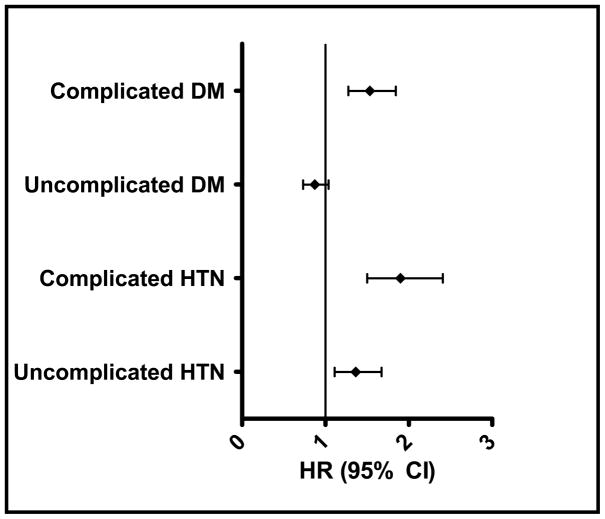

In a separate regression model, we explored whether the severity of HTN and DM had an impact on the risk of CRVO. After adjustment for confounding factors, individuals with uncomplicated HTN had a 36% increased risk of CRVO (HR = 1.36 [95% CI: 1.11–1.67]) compared to those without HTN. Individuals with end-organ damage from HTN had a 92% increased hazard of being diagnosed with CRVO (HR = 1.92 [95% CI: 1.52–2.42]) relative to individuals with no record of HTN. Enrollees with no end-organ damage from DM were not at increased risk for CRVO (HR = 0.87 [95% CI: 0.73–1.04]) while individuals with end-organ damage from DM had a 53% increased hazard of CRVO (HR = 1.53 [95% CI: 1.28–1.84]) compared to those without DM (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of Severity of Diabetes and Hypertension on Risk of Being Diagnosed with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed requiring a second (confirmatory) diagnosis of CRVO to classify an enrollee with this condition. Using two codes to confirm the diagnosis of CRVO decreased the number of CRVO cases from 1,302 to 698. However, the results did not materially change from those obtained with the original models (results not shown).

Discussion

While HTN is generally accepted as a risk factor for CRVO, the relationship between CRVO and other systemic medical conditions or sociodemographic variables is less clearly defined. In the present analysis, we confirmed that HTN is an important predictor of CRVO and showed that individuals with complicated DM are also at increased risk of CRVO. Consistent with the hypothesis that atherosclerosis of the central retinal artery in the lamina cribrosa may contribute to CRVO44 is our finding that a prior stroke or the presence of PAD increased the hazard of CRVO. We also showed that hypercoagulable state increased the risk of CRVO by more than twofold, suggesting that venous disorders may play an important role in the pathogenesis of CRVO as well. Finally, we identified black race as a sociodemographic risk factor for CRVO and showed that complicated DM is associated with an increased hazard of CRVO while uncomplicated DM does not increase the risk of CRVO.

Hypertension

Our finding that HTN is a significant risk factor for CRVO is consistent with the results of multiple prior investigations.7–16 HTN is known to accelerate the arterial stiffness that accompanies aging,45 and hardening of the central retinal artery within the lamina cribrosa has been postulated to compress the adjacent central retinal vein, thus creating turbulent blood flow and facilitating thrombosis.26 Our analysis demonstrates that both uncomplicated and complicated HTN are risk factors for CRVO, suggesting that the effects of HTN on retinal arterial structure place patients at increased risk for CRVO even before other systemic complications of HTN arise.

Diabetes Mellitus

In concordance with other studies we did not find an association between DM and CRVO after controlling for HTN, HLD, and multiple other covariates. Other studies have similarly been unable to show a relationship between DM and CRVO.8,13,37 However, a recent meta-analysis showed that DM was a significant risk factor for CRVO16 as did several other studies.9,10,31 Our study may partially explain the variable findings among reports in the literature, as stratification of DM patients into those with and without complications led to two disparate results. That is, complicated DM increased the risk of CRVO while uncomplicated DM had no effect on the risk of being diagnosed with CRVO. In other studies that included patients with various stages of DM, it is possible that patients with uncomplicated DM masked the significant effect of complicated DM on CRVO risk.

Hyperlipidemia

Like DM, HLD was not found to be a significant risk factor for CRVO in our model, which corroborates the findings from other investigations.18,37 However, other studies have found a significant association between CRVO and HLD.11,16,35,36 There are several potential explanations for these conflicting results. While HLD is an accepted risk factor for atherosclerosis, it does not appear to reduce arterial compliance until late in the disease course. In fact, early HLD is actually associated with increased arterial compliance in experimental animals, and only later in the course of the disease do the arteries become more rigid.45 This suggests that the duration and severity of HLD may influence the extent of atherosclerosis in the central retinal artery, which could, in turn, affect the risk of developing a CRVO. Studies evaluating the relationship between CRVO and HLD, including ours, often do not account for the duration or severity of HLD. Furthermore, the study design that we used can detect associations but cannot determine causality. Thus, while the mechanisms that we propose seem biologically plausible, we are unable to draw on any hard conclusions about how the severity or duration of HLD might affect CRVO risk. Another potential explanation for the unclear relationship between HLD and CRVO involves the use of the lipid-lowering agents called statins. These drugs have vaso-protective and anti-atherogenic properties, and in one study they were shown to actually halt the progression of atherosclerosis in patients requiring coronary angiography.46 However, none of the studies to date have accounted for statin use.

Arterial Disease

Consistent with the hypothesis that atherosclerosis contributes to the development of CRVO, we found that other diseases caused by atherosclerosis, such as PAD and stroke, are associated with increased CRVO risk. This suggests that atherosclerosis occurring elsewhere in the body may be a surrogate marker for atherosclerosis occurring in the central retinal artery. Support for this statement comes from other studies that have shown a relationship between stroke and CRVO. For example, one study of over 3,600 Australians found that a history of stroke or angina significantly increased RVO risk,21 and a more recent report found a significant association between carotid artery plaque and RVO.47 However, a study of 612 patients with CRVO did not find an association between either stroke or PAD and CRVO,15 and another study of 144 patients who had CRVOs failed to show any association between history of stroke and CRVO.18 Both PAD and stroke appeared to have minor, though significant, effects on the risk of CRVO in our study, suggesting that a large sample size may be required to capture the impact of these conditions on CRVO risk.

Venous Disease

The role of hypercoagulability in causing retinal vein occlusions is controversial, as prior investigations have yielded conflicting results. Most of these analyses have examined the association between individual coagulopathies (e.g., Factor V Leiden mutation, Prothrombin gene mutation, etc.) and RVO. In 2005, Janssen et al. conducted a meta-analysis to more fully understand how specific coagulopathies affect the risk of developing an RVO, and they found that hyperhomocysteinemia and the presence of anti-phospholipid antibodies each had a significant association with RVO.48 However, more traditional risk factors for venous thrombosis (e.g., Factor V Leiden and the Prothrombin gene mutation) were not significantly associated with RVO. Their results corroborate the findings from several smaller case-control studies evaluating coagulopathies and the risk of CRVO.22–25,27,35 Our finding that the diagnosis of a primary or secondary hypercoagulable state is associated with CRVO also supports the results of these earlier studies.

The pathogenesis of CRVO among young, hypercoagulable patients is likely different than that seen in older patients with atherosclerosis. A study of 228 patients who developed RVOs found that thrombophilic disorders were common in the group of patients with RVO who were either ≤ 45 years old or who lacked any cardiovascular risk factors.49 This suggests that patients with coagulopathies may experience unprovoked thrombus formation in the central retinal vein as a result of their underlying thrombophilia (and not as a consequence of turbulent flow induced by compression of the vein by a nearby atherosclerotic artery). Importantly, this information can be used to help physicians identify which patients who have RVOs should be screened for coagulation disorders (namely those patients who are ≤ 45 years old and who lack any cardiovascular risk factors).

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Our results indicate that blacks are at increased risk for CRVO compared to whites which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously reported in the literature. In a population-based cross-sectional study, Cheung et al. showed that the prevalence of any type of RVO was similar across different races.50 However, there was no adjustment for confounding variables in their analysis. The increased risk for CRVO that we observed in blacks compared to whites can potentially be attributed to genetic variability between the races, as known comorbid medical conditions, glaucoma, and socioeconomic status were all adjusted for in this analysis.

Rath et al. reported that race was not a significant risk factor for CRVO but that male sex was a risk factor for the condition.8 We too found that males were more likely to be diagnosed with a CRVO than females. The increased risk of CRVO in males compared to females could be due to genetic and hormonal differences between the sexes or to the higher prevalence of atherosclerosis observed in men. While we attempted to adjust for multiple measures of atherosclerosis in our model, it remains possible that not all patients with atherosclerosis were identified using the available ICD-9-CM codes.

Interestingly, we found that those with a household net worth >$500,000 had a decreased risk of CRVO compared to those with a net worth <$25,000. This might be a result of better access to care (even though all the enrollees had health insurance), differences in lifestyle factors, or greater adherence with diabetes, lipid-lowering, and anti-hypertensive medications in the more affluent group.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, using claims data afforded us with a large sample size that included substantially more subjects than any of the prior studies. Furthermore, we were able to adjust for many potential confounders in our analysis, which allowed us to identify independent risk factors for CRVO. Finally, the claims data we used is from enrollees across the country, which makes our results generalizable to individuals enrolled in managed care networks throughout the US.

There are several study limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, relying on claims data rather than clinical data precluded us from identifying patients who may have been misdiagnosed or miscoded with CRVO. To help address this concern, we reran our models in a sensitivity analysis that required a confirmatory diagnosis of CRVO and the results did not change significantly. Second, all enrollees had health insurance through a managed care network, so our findings may not be generalizable to patients with other types of health insurance (such as traditional Medicare or private insurance), those who are uninsured, or those receiving care in other countries. Third, we were only able to evaluate variables with ICD-9-CM codes, so we were unable to include information about potentially important factors such as blood pressure levels, body-mass index, dietary habits, intake of vitamins and supplements, alcohol consumption, exercise programs, and tobacco use. Likewise, we could not tell from claims data alone which CRVOs were ischemic or non-ischemic and whether some of these risk factors were associated with good or poor outcomes as measured by best corrected visual acuity. Finally, our analysis was partially limited by the fact that we could only adjust for known confounders, and other unknown variables could still be affecting our results.

In summary, CRVO is a sight-threatening condition that affects roughly 1 in 1500 people worldwide.2 In addition to the known risk factors for CRVO such as HTN and glaucoma, we have identified or confirmed other variables (such as black race, male sex, PAD, stroke, complicated DM, and hypercoagulable state) that are associated with CRVO. Furthermore, the finding that individuals with end-organ damage from DM are at increased risk for CRVO while those with uncomplicated DM are not may explain the inconsistent literature surrounding the association between DM and CRVO. However, given some of the aforementioned limitations of this retrospective analysis, confirmation of our findings in prospective studies is warranted. Finally, further studies are also needed to better understand how the treatment or modification of the identified risk factors affects the chances of developing RVO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: National Eye Institute K23 Mentored Clinician Scientist Award (JDS:1K23EY019511-01); Michigan Eye Bank (JDS); Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation (JDS); Alliance for Vision Research grant (JDS); American Diabetes Association-Merck Clinical/Translational Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (MSS)

The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

No conflicting relationship exists for any author regarding any material discussed in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cugati S, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Ten-year incidence of retinal vein occlusion in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:726–32. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, et al. International Eye Disease Consortium. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branch Vein Occlusion Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for macular edema in branch vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:271–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Vein Occlusion Study Group. Natural history and clinical management of central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:486–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150488006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan CK, Ip MS, Vanveldhuisen PC, et al. SCORE Study Investigator Group. SCORE Study report #11: incidences of neovascular events in eyes with retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1364–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Singh RP, et al. CRUISE Investigators. Ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1124–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elman MJ, Bhatt AK, Quinlan PM, Enger C. The risk for systemic vascular diseases and mortality in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1543–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rath EZ, Frank RN, Shin DH, Kim C. Risk factors for retinal vein occlusions. A case-control study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:509–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31940-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:545–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sperduto RD, Hiller R, Chew E, et al. Risk factors for hemiretinal vein occlusion: comparison with risk factors for central and branch retinal vein occlusion: the Eye Disease Case-Control Study. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:765–71. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)95012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcucci R, Bertini L, Giusti B, et al. Thrombophilic risk factors in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:772–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shahsuvaryan ML, Melkonyan AK. Central retinal vein occlusion risk profile: a case-control study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2003;13:445–52. doi: 10.1177/112067210301300505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumus K, Kadayifcilar S, Eldem B, et al. Is elevated level of soluble endothelial protein C receptor a new risk factor for retinal vein occlusion? Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:305–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maier R, Steinbrugger I, Haas A, et al. Role of inflammation-related gene polymorphisms in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B, McCarthy MJ, Podhajsky P. Systemic diseases associated with various types of retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:61–77. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Mahoney PR, Wong DT, Ray JG. Retinal vein occlusion and traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:692–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirota A, Mishima HK, Kiuchi Y. Incidence of retinal vein occlusion at the Glaucoma Clinic of Hiroshima University. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:288–91. doi: 10.1159/000310810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koizumi H, Ferrara DC, Brue C, Spaide RF. Central retinal vein occlusion case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:858–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luntz MH, Schenker HI. Retinal vascular accidents in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;25:163–7. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(80)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appiah AP, Trempe CL. Risk factors associated with branch vs. central retinal vein occlusion. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989;21:153–5. 157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell P, Smith W, Chang A. Prevalence and associations of retinal vein occlusion in Australia: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1243–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140443012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalayci D, Gurgey A, Guven D, et al. Factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210 A mutations in patients with central and branch retinal vein occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:622–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamczuk YP, Iglesias Varela ML, Martinuzzo ME, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion and thrombophilia risk factors. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13:623–6. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fegan CD. Central retinal vein occlusion and thrombophilia. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:98–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahey JM, Tunc M, Kearney J, et al. Laboratory evaluation of hypercoagulable states in patients with central retinal vein occlusion who are less than 56 years of age. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:126–31. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prisco D, Marcucci R, Bertini L, Gori AM. Cardiovascular and thrombophilic risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Eur J Intern Med. 2002;13:163–9. doi: 10.1016/s0953-6205(02)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahey JM, Kearney JJ, Tunc M. Hypercoagulable states and central retinal vein occlusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:385–92. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao W, Wang YS, Zhang P, Wang HY. Hyperhomocysteinemia and low plasma folate as risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion: a case-control study in a Chinese population. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:1246–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narayanasamy A, Subramaniam B, Karunakaran C, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia and low methionine stress are risk factors for central retinal venous occlusion in an Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1441–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glueck CJ, Wang Ping, Hutchins R, et al. Ocular vascular thrombotic events: central retinal vein and central retinal artery occlusions. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2008;14:286–94. doi: 10.1177/1076029607304726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein R, Moss SE, Meuer SM, Klein BE. The 15-year cumulative incidence of retinal vein occlusion: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:513–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moghimi S, Najmi Z, Faghihi H, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia and central retinal vein occlusion in Iranian population. Int Ophthalmol. 2008;28:23–8. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sodi A, Giambene B, Marcucci R, et al. Atherosclerotic and thrombophilic risk factors in patients with recurrent central retinal vein occlusion. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:233–8. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thapa R, Paudyal G. Central retinal vein occlusion in young women: rare cases with oral contraceptive pills as a risk factor. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009;11:209–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo JZ, Lai CC, Ong FS, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion in a young Chinese population: risk factors and associated morbidity and mortality. Retina. 2010;30:479–84. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181b9b3a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sodi A, Giambene B, Marcucci R, et al. Atherosclerotic and thrombophilic risk factors in patients with ischemic central retinal vein occlusion. Retina. 2011;31:724–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181eef419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadayifcilar S, Ozatli D, Ozcebe O, Sener EC. Is activated factor VII associated with retinal vein occlusion? Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1174–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.10.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rehak M, Rehak J, Muller M, et al. The prevalence of activated protein C (APC) resistance and factor V Leiden is significantly higher in patients with retinal vein occlusion without general risk factors. Case-control study and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:925–9. doi: 10.1160/TH07-11-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaghoubi GH, Madarshahian F, Mosavi M. Hyperhomocysteinaemia: risk of retinal vascular occlusion. East Mediterr Health J. 2004;10:633–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGimpsey SJ, Woodside JV, Bamford L, et al. Retinal vein occlusion, homocysteine, and methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase genotype. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4712–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein ML, Francis PJ, Ferris FL, III, et al. Risk assessment model for development of advanced age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1543–50. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Meuer SM. The epidemiology of retinal vein occlusion: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:133–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saatci OA, Ferliel ST, Ferliel M, et al. Pseudoexfoliation and glaucoma in eyes with retinal vein occlusion. Int Ophthalmol. 1999;23:75–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1026557029227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yau JW, Lee P, Wong TY, et al. Retinal vein occlusion: an approach to diagnosis, systemic risk factors and management. Intern Med J. 2008;38:904–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benetos A, Waeber B, Izzo J, et al. Influence of age, risk factors, and cardiovascular and renal disease on arterial stiffness: clinical applications. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:1101–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)03029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nissen SE. Halting the progression of atherosclerosis with intensive lipid lowering: results from the Reversal of Atherosclerosis with Aggressive Lipid Lowering (REVERSAL) trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl):22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong TY, Larsen EK, Klein R, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors for retinal vein occlusion and arteriolar emboli: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities and Cardiovascular Health studies. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:540–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janssen MC, den Heijer M, Cruysberg JR, et al. Retinal vein occlusion: a form of venous thrombosis or a complication of atherosclerosis? A meta-analysis of thrombophilic factors. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:1021–6. doi: 10.1160/TH04-11-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuhli-Hattenbach C, Scharrer I, Luchtenberg M, Hattenbach LO. Coagulation disorders and the risk of retinal vein occlusion. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:299–305. doi: 10.1160/TH09-05-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheung N, Klein R, Wang JJ, et al. Traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factors for retinal vein occlusion: the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4297–302. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.