Abstract

Objective

Un Abrazo Para La Familia [A Hug for the Family] is an intervention designed to increase the accessibility of cancer information to low-income and medically underserved co-survivors of cancer. Co-survivors are family members or friends of an individual diagnosed with cancer. Our goal was to increase socio-emotional support for co-survivors, and improve skills in coping with cancer. The purpose of our pilot study was to explore the effectiveness of the intervention in increasing cancer knowledge and self-efficacy among co-survivors.

Methods

Un Abrazo consisted of three one-hour sessions, in either Spanish or English. Sessions were delivered by a trained promotora [community health worker], in partnership with a counselor. Sixty participants completed measures of cancer knowledge and self-efficacy preceding (pre-test) and following the intervention (post-test).

Results

From pre- to post-test, the percentage of questions answered correctly about cancer knowledge increased (p < .001), as did ratings of self-efficacy (p < .001). Decreases were seen in “Do not know” responses for cancer knowledge (p < .01), with a negative correlation between number of “Do not knows” on cancer knowledge at pre-test and ratings of self-efficacy at pre-test (r = −.47, p < .01).

Conclusions

When provided an accessible format, co-survivors of cancer from underserved populations increase their cancer knowledge and self-efficacy. This is notable because research indicates that family members and friends with increased cancer knowledge assume more active involvement in the cancer care of their loved ones.

Keywords: low-income, Hispanic, cancer knowledge, oncology, co-survivors, self-efficacy

The work of families facing cancer is both bolstered and informed by culture and social class—by family values, beliefs, customs, and language [1]. Families include persons important to the individual with cancer: partners, relatives, friends, etc. [2]. Family members can be as deeply affected by the cancer experience as the cancer survivors themselves [3]. The term “co-survivor” is emerging in the literature, in part, it would appear, to clarify survivor status between those who have been diagnosed with cancer and those who have been affected by the diagnosis. It is understood that “co-survivors can be family members, spouses or partners, friends, health care providers or colleagues….” (http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/FriendsampFamily.html). Co-survivors of cancer may suffer post-traumatic stress from the cancer experience if their needs and concerns are not addressed [4]. A recent Institute of Medicine [5] report identified six domains of inadequately addressed psychosocial problem areas to include patient and family understanding of the illness, treatments, and services.

Researchers have reported that “the adverse effect of living with someone else’s cancer may be assuaged through the provision of information, education, and support” [6, p. 129]. In particular, researchers have found that co-survivor beliefs of mastery and self-efficacy can serve as protective factors in caregiving situations [7]. Self-efficacy has been defined and measured as “confidence in one’s ability to complete a task” [8, p. 112S]. Badger and colleagues [9] found when cancer information was supplied in an accessible format to prostate cancer survivors and their partners that cancer knowledge, self-efficacy and quality of life increased. Further, education about cancer can decrease the psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their co-survivors [10]. Interventions that train cancer patients and their families to take a more active role in their care and to ask more appropriate and relevant questions (i.e., patient activation) can improve health outcomes [11], as can providing social support [12]. To date, however, few interventions have specifically addressed the needs of low-income and underserved families. To this end, in our previous work, we called for attention both in research and in interventions to include a greater focus on culture and social class [1] as a way to better understand the needs and experiences of co-survivors of cancer in low-income families [13].

We named the intervention Un Abrazo Para La Familia [A Hug for the Family] because the warm connotations of friendship and trust address important cultural values of the Hispanic community. The intervention, here referred to as “Un Abrazo,” was developed to address the unmet informational needs of low-income co-survivors, to both increase both cancer knowledge and self-efficacy. The conceptual framework for the intervention reflects a pairing of family systems [14, 15]and sociocultural theory [16] to address the need for consideration of social class and culture [1]. Further, this understanding of the family is aided by viewing co-survivors’ experiences as part of a biopsychosocial model within a cancer-related system: that is, a system that includes the cancer itself, the patient, the family, the medical team and the community [17].

Methods

Un Abrazo was provided as a community health outreach service in the metro area of a mid-sized city in the southwestern United States. In the state, a third of Hispanic working-age adults are without insurance coverage [18]. More than a third (39%) of Hispanics have less than a high school education [19]. Given their lack of health care coverage and low educational attainment, Hispanics in the state are considered to be at risk for being medically underserved [20]. In the south and west sections of the city where this work was concentrated, over 60% of the population is Hispanic (Mexican-American). The work was carried out during 2010 in partnership with a federally qualified community health center that primarily serves low-income and underserved populations and where 70,000 patients access services annually. Community members were advised of the program through the outreach efforts of a promotora [community health worker] employed by the partner community health center. The promotora distributed program flyers in both English and Spanish to local oncology service providers and at health fairs, by visiting community health and parent support programs at public schools, by networking with other promotoras, and on Spanish community radio.

Participants

Although eligibility requirements for the Un Abrazo classes included being either survivors or co-survivors of breast cancer and being age 18 or older, the majority of participants, 83% (n=60), were co-survivors. The data reported here refer to these 60 participant co-survivors. The vast majority of the co-survivors were women (96.7%, n = 58). All reported being Hispanic. Preferences of spoken and written language were for Spanish over English (both above 83%). Age ranged from 25 to 69 (Mdn = 38, SD = 8.68). The majority were married (73%). In terms of education, 40% of the participants reported having completed less than a high school education. The median and mode number of years of education completed was 12 (SD = 3.65), with a range of 2 to 17 years. Half of the individuals reporting having some form of health insurance, while the other half said that they did not have health insurance. The majority (n = 44, 73.3%) used financial support such as food stamps. Most participants reported being unemployed (54.2%), followed by being a housewife (16.9%), working part-time (15.3%), or working full-time (13.6%).

As for the relationship to the loved one with cancer, most co-survivors were relatives. Among the relatives were daughters (18.3%), nieces (11.7%), and cousins (10%); sisters, granddaughters, and sisters-in-law (5% each); spouses or the participant had multiple family members with cancer (3.3% each); as well as mother, neighbor, daughter-in-law, and grandniece (1.7% each). Following relatives, the balance of co-survivors identified as friends of the person with cancer (21.7%). About one third of the participants (31.7%) knew the year of diagnosis of their loved one (n=7, 2010; n=9, 2009; n=1, 2005; n=1, 1991; n=1, 1993), with the vast majority (84.2%) participating in the intervention within a year or two of the diagnosis.

Design and procedure

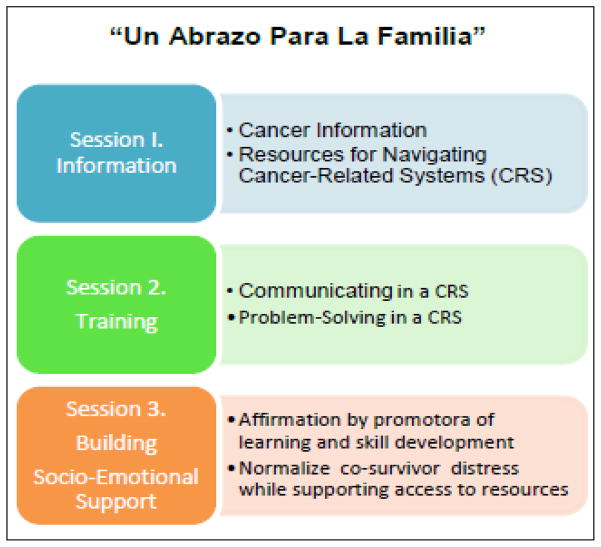

The design for the study was a pre- and post-intervention evaluation. Our intervention was offered as a free community health service with classes scheduled as needed to meet community or family requests for the intervention. The intervention was tailored to meet the needs of low-income, ethnically diverse, and medically underserved community [13] and thus designed to increase the accessibility of psychosocial cancer information to co-survivors of cancer near the time of a cancer diagnosis. Each class consisted of three hours of informational and skill-building modules or sessions (see Figure 1)2 and averaged 6.5 participants. Classes were delivered collaboratively by a trained counselor and a promotora, and provided a) evidence-based cancer information about coping with cancer and caregiving, b) explanation of depression as a treatable illness and not unexpected with cancer, and c) information about the risks of breast cancer. Class time was also allocated for demonstration and practice of communication and problem-solving skills, and providing emotional support. Classes were held in participant homes and other natural gathering places such as public libraries, public health clinics serving underinsured and uninsured patients, and public schools. The classes were delivered in Spanish or English, tailored to the language preferences of participants.

Figure 1.

Un Abrazo Para La Familia Session Topics

Outcome measures and data collection

Before content was shared at the first intervention session of each class, participants completed a 12-item modified version of the Cancer Knowledge Questionnaire (CKQ). The CKQ was chosen to measure participants’ cancer-related knowledge, which is known to be a first step in mastery and coping with cancer [7]. The CKQ has good content validity for measuring the effectiveness of our cancer education intervention. It assesses understanding of terms and concepts commonly used in breast cancer education materials and medical records [21, 22] and has acceptable reliability as reported by internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .83) [22]. The CKQ was read aloud by both session leaders and participants in turn, to assure low literacy was not a barrier to understanding the questions. Responses were marked individually by participants. Example CKQ items include, “Cancers are usually named for the body organ or tissue that was the starting place of the growth,” and “If untreated, breast cancer may spread to other parts of the body.” Response choices are True, False, or Don’t know.

Participants were also asked to respond to a measure of self-efficacy regarding cancer knowledge via the statement: “I am confident that my knowledge of cancer and its treatment is enough for me to be able to do what I need to do.” Response is given via a 10-point scale ranging from Not true about me (1) to True about me (10). This measure has a reported significant correlation with items on the CKQ) (r = .25) [21].

The CKQ and self-efficacy measure were completed by participants a second time after the Un Abazo intervention sessions (post-test). In consultation with the Human Subjects Protection Program of The University of Arizona, it was determined that the study was exempt from further review by the institutional review board because it qualified as program evaluation only. However, participants were advised via a document, titled “Guidelines of Participation” and available in Spanish or English, that: “You will be asked to complete a questionnaire before the first meeting and after the last meeting” and “You may choose not to answer some or all of the questions.”

Data analysis

We documented the extent to which the program had an effect on the participants’ cancer knowledge and cancer-related self-efficacy. Our position was that establishing improvement or benefit in these two areas would be pre-requisite for further evaluation of this program and for this population. We use paired sample t-tests and Pearson correlations as appropriate to test the effectiveness of the Un Abrazo program. That is, scores should be improved in the post-test when compared to the pre-test. We report sample sizes for each analysis as the sample size varied depending upon those available to complete the post-test. We used SPSS version 19 for all analyses.

Results

Self-Efficacy and Cancer Knowledge

From pre- to post-test, self-efficacy significantly increased for co-survivors [t(30) = −7.58, p < .001], with a pre-test mean result of 4.97 (SD = 2.50), compared to a post-test mean of 8.29 (SD = 1.40), almost twice as high. Additionally, the percentage of questions answered correctly about cancer knowledge significantly increased for co-survivors [t(35) = −8.37, p < .001], with a pre-test mean of 6.28 (SD = 2.08), compared to a post-test mean of 9.56 (SD = 1.76).

We assessed the number of Don’t know responses on cancer knowledge from pre- to post-test. Subsequent analyses reported here were limited to those participants (n = 10) who reported at least one Don’t know response on the cancer knowledge items. From pre- to post-test, significant decreases were seen in Don’t know responses regarding cancer knowledge [t(9) = 5.91, p < .001]. The pre-test mean was 5.40 (SD = 1.35, n = 10) compared to the post-test mean of 2.10 (SD = 1.73, n = 10) for “Don’t know” responses.

Finally, we summed across the 12 items of cancer knowledge from the pre-test to create a composite score for Don’t know responses. We then correlated this new summed variable with self-efficacy at pre-test. As we expected, the correlation between the number of Don’t know responses on cancer knowledge at pre-test and ratings of self-efficacy at pre-test for co-survivors was significantly negative [r = −.47, p < .01, n = 49]. However, this finding did not hold true at the post-test, most likely due to the much smaller sample size of individuals giving Don’t know responses [r = −.32, p = .37, n = 10.]

Discussion and Conclusion

When provided a tailored and accessible intervention, co-survivors of cancer from an underserved population of low-income, Spanish-speaking Hispanics, increased their cancer knowledge and feelings of self-efficacy. We expect these co-survivors may use this knowledge and self-efficacy to better access support for themselves, and are better positioned to support their family member with cancer. Using the Un Abrazo framework to deliver the cancer education via promotoras may result in a preventive intervention approach for families facing the stress of a cancer diagnosis by building both mastery and confidence found to be effective in managing stress and found to serve as protective factors against depression in caregiving situations. Our findings are notable and important given that previous research has documented that family members and friends with increased cancer knowledge assume more active involvement in the cancer care of their loved ones and ask more appropriate and relevant questions.

Finally, our results offer public and private health care delivery systems a rational approach to facilitate the supportive role family members can provide cancer survivors by providing preventive interventions specifically designed for co-survivors of cancer. By making informed, evidenced-based, culturally-relevant cancer-related information and support more readily accessible to family members, health care providers may reduce stress felt by co-survivors and enable them to more readily and effectively assist their loved ones with cancer.

Limitations and Future Work

The promising findings from the current evaluation should be viewed in light of the study’s limitations. First, the study design did not include a control group. However, the strong and consistent pattern of findings suggests it was the intervention rather than mere time that made the difference in both cancer knowledge and self-efficacy/confidence gains. Replication using a control group design would be a productive direction for future research. Second, we relied on a one-item measure of self-efficacy/confidence which could raise questions about measurement reliability for that construct. Future research will use a multi-dimensional, multi-item measure of efficacy/confidence and/or triangulate by also using qualitative techniques (e.g., open-ended questions that may tap this construct).

One of the strengths of this project was the multi-faceted nature of the intervention. However, given the study design, we are unable to determine which features or components of the intervention were most effective and whether all features and components are required for success. For instance, because there is a high need for psychosocial support in this population of co-survivors, it would be important to assess the level of support perceived as a result of this intervention and any interactions between the psychosocial and informational resources provided and perceived support. Additional research that addresses these factor effects and interactions would be valuable not only to further refine the intervention, but also to help maintain cost effectiveness of future intervention efforts.

The theme of having unmet informational needs was pervasive in our previous qualitative study of low-income, predominately Hispanic co-survivors of cancer who reported cancer-related stress [13]. Our findings as reported here are similar to, yet extend the literature about, family information needs as found with predominately White, middle class samples [23] and support recommendations that tools and strategies are needed to ensure delivery of appropriate psychosocial services to populations with low literacy and inadequate income, as well as members of minority communities [5]. To address the psychosocial needs identified by the Institute of Medicine and others, we propose to continue our work in delivering family-focused cancer education in low-income and ethnically-diverse populations, thereby increasing family members’ knowledge about cancer and its treatment. Initiating family-focused preventive intervention appears warranted before cancer-associated anxiety, depression, and stress require clinical treatment.

Acknowledgments

Research leading to the development of the program described here was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Individual Senior Fellowship (Grant Number F33CA117704), the Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to the Southern Arizona Affiliate of Susan G. Komen for the Cure® for funding the program as here described. The program funding was awarded to the El Rio Health Center Foundation and we thank Susan Marks, MPH, El Rio Health Center Community Health Coordinator, for her support and vision of our partnership. We also thank Katerina Sinclair, Ph.D., Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth, & Families, Norton School of Family & Consumer Sciences, the University of Arizona, for her early guidance in our program evaluation. Finally, we we thank the program particpants without whom this work would not be possible.

Footnotes

Curriculum guides for each session are available upon request from the first author.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Catherine A. Marshall, Email: marshall@email.arizona.edu, Center of Excellence in Women’s Health, Frances McClelland Associate Research Professor, Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth, & Families, Norton School of Family & Consumer Sciences, University of Arizona, Room 235L, 650 North Park Avenue/PO Box 210078, Tucson, AZ 85721-0078, phone: 520-621-1539, fax: 520-621-9445.

Terry A. Badger, Email: tbadger@nursing.arizona.edu, Community and Systems Health Science Division, College of Nursing, University of Arizona, 1305 N. Martin, PO Box 210203, Tucson, AZ 85721, phone: 520-626-6058, fax: 520-626-7891.

Melissa A. Curran, Email: macurran@email.arizona.edu, Family Studies and Human Development, University of Arizona, 650 N. Park McClelland Park, Tucson, AZ 85721-0078, phone: 520-621-7140, fax: 520-621-9445.

Susan Silverberg Koerner, Email: koerner@email.arizona.edu, Division of Family Studies & Human Development, P.O. Box 210078, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0078, phone: 520-621-1691, fax: 520-621-9445.

Linda K. Larkey, Email: Linda.Larkey@asu.edu, Scottsdale Healthcare Chair of Biobehavioral Oncology Research, College of Nursing and Health Innovation at Arizona State University, 500 N. 3rd Street, Phoenix, Arizona 85004, phone: 602-496-0740.

Karen L. Weihs, Email: weihs@email.arizona.edu, Psychosocial Oncology Program, University of Arizona, University of Arizona Medical Center, Room 7306D, 1501 N Campbell Ave., Tucson, AZ 85724-5002, phone: 520-626-8940, fax: 520-626-6050.

Lorena Verdugo, Email: lorenav@elrio.org, El Rio Community Health Center, 3480 E. Britannia Dr. Ste. 120, Tucson, AZ 85706, (520) 370-3686 Phone, (520) 670-3792 Fax.

Francisco A. R. García, Email: fcisco@email.arizona.edu, Distinguished Professor of Public Health, and Obstetrics & Gynecology, Director of the University of Arizona Center of Excellence in Women’s Health, University of Arizona, P.O. Box 210477, 1632 East Lester Street, Tucson, AZ 85721-0477, phone: 520-626-8539, fax: 520-626-8339.

References

- 1.Marshall CA, Larkey LK, Curran MA, Weihs KL, Badger TA, Armin J, García F. Considerations of culture and social class for families facing cancer: The need for a new model for health promotion and psychosocial intervention. Families, Systems, & Health. 2011;29(2):81–94. doi: 10.1037/a0023975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sample S. We Are Family: Coping with Cancer in the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgendered Community. In: Marshall CA, editor. Surviving Cancer as a Family and Helping Co-Survivors Thrive. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger; 2010. pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 3.A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control and the Lance Armstrong Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum A, Posluszny DM. Traumatic stress as a target for intervention with cancer patients. In: Baum A, Andersen BL, editors. Psychosocial interventions for cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler NE, Page A, editors. Institute of Medicine. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland G, Dpsych LH, White V, Jefford M, Hegarty S. How Does a Cancer Education Program Impact on People With Cancer and Their Family and Friends? Journal of Cancer Education. 2008;23(2):126–132. doi: 10.1080/08858190802039177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaugler JE, Linder J, Given CW, Kataria R, Tucker G, Regine WF. Family Cancer Caregiving and Negative Outcomes: The Direct and Mediational Effects of Psychosocial Resources. Journal of Family Nursing. 2009;15(4):417–444. doi: 10.1177/1074840709347111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke NJ, Bird JA, Clark MA, Rakowski W, Guerra C, Barker JC, Pasick RJ. Social and Cultural Meanings of Self-Efficacy. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(5 Suppl):111S–128S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badger T, Segrin C, Figueredo A, Harrington J, Sheppard K, Passalacqua S, Pasvogel A, Bishop M. Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life in prostate cancer survivors and their intimate or family partners. Quality of Life Research. 2011;33 (5):450–464. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9822-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesters I, van den Borne B, De Boer M, Pruyn J. Measuring information needs among cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2001;43(3):255–264. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendren S, Griggs JJ, Epstein RM, Humiston S, Rousseau S, Jean-Pierre P, Carroll J, Yosha AM, Loader S, Fiscella K. Study Protocol: A randomized controlled trial of patient navigation-activation to reduce cancer health disparities. BMC Cancer. 2010;10 (1):551. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, Mizrahi J, Enright TM, Hunt ME, Siegel RS. Dependable social relationships predict overall survival in Stages II and III breast carcinoma patients. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2005;59(5):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall CA, Weihs KL, Larkey LK, Badger TA, Koerner SS, Curran MA, Pedroza R, García F. “Like a Mexican wedding”: The psychosocial intervention needs of predominately Hispanic low-income female co-survivors of cancer. Journal of Family Nursing. 2011;17 (3):380– 402. doi: 10.1177/1074840711416119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minuchin PCJ, Minuchin S. Working with families of the poor. 2. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantor D, Lehr W. A systems approach. San Francisco: Josey-Bass; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogoff B. The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weihs K, Reiss D. Family reorganization in response to cancer: A developmental perspective. In: Baider LCLC, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the family. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill K, Hoffman D, Welch N, Hart W, Hall JS, Hughes R, Rissi J. Truth and consequences: Gambling, shifting, and hoping in Arizona health care. Phoenix, Arizona: Morrison Institute for Public Policy, School of Public Affairs, College of Public Programs, Arizona State University. Center for Competitiveness and Prosperity Research, L. William Seidman Research Institute, W.P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University. St. Luke’s Health Initiatives; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welch N. AZ Workforce: Latinos, Youth and the Future. Phoenix, Arizona: Morrison Institute for Public Policy, School of Public Affairs, College of Public Programs, Arizona State University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arizona Cancer Facts and Figures, 2004–2005: A Sourcebook for Planning and Implementing Programs for Cancer Prevention and Control. Phoenix, AZ: American Cancer Society, Great West Division, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braden C, Mishel M, Longman A. Self-help intervention project. Women receiving breast cancer treatment. Cancer Practice. 1998;6(2):87–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.1998006087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidani S. Measuring the Intervention in Effectiveness Research. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1998;20(5):621–635. doi: 10.1177/019394599802000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason TM. Wives of men with prostate cancer postbrachytherapy: Percieved information needs and degree of being met. Cancer Nursing: An International Journal for Cancer Care. 2008;31(1):32–37. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305674.06211.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]