Highlights

► Feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) is a causative agent of a fatal disease among cats. ► Protease inhibitors targeting virus 3C/3CL protease potently inhibited feline infectious peritonitis virus in cells. ► The antiviral effects of inhibitors were compared with a cathepsin B inhibitor, an entry blocker. ► The inhibitors exerted strong synergistic effects with a cathepsin B inhibitor against a FIPV in cells.

Keywords: Feline coronaviruses, Feline infectious peritonitis virus, Protease inhibitor, Cathepsin B, Synergy, 3CL protease

Abstract

Feline coronavirus infection is common among domestic and exotic felid species and usually associated with mild or asymptomatic enteritis; however, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a fatal disease of cats that is caused by systemic infection with a feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), a variant of feline enteric coronavirus (FECV). Currently, there is no specific treatment approved for FIP despite the importance of FIP as the leading infectious cause of death in young cats. During the replication process, coronavirus produces viral polyproteins that are processed into mature proteins by viral proteases, the main protease (3C-like [3CL] protease) and the papain-like protease. Since the cleavages of viral polyproteins are an essential step for virus replication, blockage of viral protease is an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Previously, we reported the generation of broad-spectrum peptidyl inhibitors against viruses that possess a 3C or 3CL protease. In this study, we further evaluated the antiviral effects of the peptidyl inhibitors against feline coronaviruses, and investigated the interaction between our protease inhibitor and a cathepsin B inhibitor, an entry blocker, against a feline coronavirus in cell culture. Herein we report that our compounds behave as reversible, competitive inhibitors of 3CL protease, potently inhibited the replication of feline coronaviruses (EC50 in a nanomolar range) and, furthermore, combination of cathepsin B and 3CL protease inhibitors led to a strong synergistic interaction against feline coronaviruses in a cell culture system.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are single stranded positive sense RNA viruses that contain the largest non-segmented RNA virus genome. Coronaviruses are responsible for highly prevalent diseases in humans and animals, and are divided into the groups alpha, beta, and gamma, based on antigenic and genetic criteria, of which alpha and beta coronaviruses infect mammals (Homes, 2001). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is classified into the beta group of coronaviruses. Feline coronaviruses belong to alpha coronaviruses and affect animals in the family Felidae, including cheetahs, wildcats, lions and leopards (Heeney et al., 1990, Kennedy et al., 2002). Feline coronavirus is further classified as serotype I or II. Feline serotype I and canine coronaviruses are considered to have originated from a common ancestor. Feline coronavirus serotype II appears to be derived from recombination with canine coronavirus and feline coronavirus serotype I in the S (spike) protein (Herrewegh et al., 1998, Motokawa et al., 1996). Feline coronavirus serotype I is more prevalent than serotype II, and feline coronaviruses of both serotypes can cause mild or asymptomatic enteritis and feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) in cats (Benetka et al., 2004, Kummrow et al., 2005, Pedersen et al., 1984a). FIP is a fatal disease in cats and currently one of the leading infectious causes of fatality among young cats in multiple cat households and shelters (Pedersen, 2009). Feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) causes asymptomatic to mild enteritis among cats with a high prevalence (Pedersen et al., 2008, Vogel et al., 2010). Unlike FECV which is confined to the intestinal epithelium, FIP virus (FIPV) gains ability to replicate in macrophages and monocytes by mutation of endogenous FECV and can spread through the entire body. The progression to FIP is also influenced by the host’s immune responses; a weak or defect in cell-mediated immune response is associated with the development of FIP (Pedersen, 2009). Despite the fatal nature and increasing incidence of FIP, no effective prophylactic or therapeutic agent is currently available for FIPV.

Coronaviruses have club-shaped S proteins on the envelope, which bind to the cells and undergo membrane fusion to gain entry into the cytoplasm. The cleavage of S proteins varies among coronaviruses. In some coronaviruses including SARS-CoV and murine hepatitis virus (MHV)-2, S proteins are cleaved by cellular cathepsins that are cysteine proteases typically present within the endosome/lysosome in the cell cytoplasm (Qiu et al., 2006, Simmons et al., 2005). FIP and FECV are also found to be highly dependent on the presence of cathepsin B for the cleavage of their S proteins, which enables cell entry for virus replication (Regan et al., 2008). The importance of the presence of cathepsin function in the replication of feline coronaviruses is demonstrated by the inhibition of some serotype I and II feline coronaviruses, including WSU-1683, WSU-1146, and DF2 strains, by a cathepsin B inhibitor CA074-Me and an irreversible non-specific cysteine inhibitor E64d by inhibiting the cleavage of S proteins (Regan et al., 2008). This result indicates that cathepsin B may serve as a potential target for the development of therapeutic drugs against feline coronaviruses.

Following entry into the cells, coronaviruses express polyproteins (pp1a and pp1b), which are cleaved by viral proteases into intermediate and mature nonstructural proteins. The viral proteases involved in the cleavage of the polyproteins are papain-like proteases (PL1pro and PL2pro) and a 3C-like (3CL) protease. The papain-like proteases cleave the N-proximal region of pp1a/pp1ab, and 3CL protease cleaves the viral polyprotein at 11 conserved interdomain junctions (Ziebuhr et al., 2000). Coronavirus proteases, like many other viral proteases such as those of human immunodeficiency virus-1 and hepatitis C virus, for which commercial protease inhibitors are available, are highly effective regulators of virus replication. Coronavirus 3CL protease is a cysteine protease that shares common characteristics in structural and functional properties with the 3CL or 3C proteases of noroviruses and picornaviruses, respectively; they possess chymotrypsin-like folds, cysteine residue as a nucleophile, and conserved active sites. Viral 3CL or 3C protease plays an essential role in viral replication; consequently, it is an attractive target for the development of antiviral drugs. Previously, we reported the generation of new peptidyl inhibitors against norovirus 3CL protease and their broad spectrum activity against viruses that possess 3C or 3CL proteases, including feline coronavirus (Kim et al., 2012, Tiew et al., 2011). In this study, we further studied the reversibility and the mode of inhibition of our 3CL protease inhibitors, and compared the antiviral effects of the 3CL protease inhibitors (GC373 and GC376) and cathepsin inhibitors against the replication of feline coronaviruses in cells. We also studied the combined antiviral effects of GC373 and CA074-Me, a cathepsin B inhibitor, against a feline coronavirus in cell culture.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the peptidyl transition state inhibitors used in this study are reversible, competitive inhibitors of 3CL protease and potently inhibit the replication of feline coronaviruses in cell culture with an EC50 (the effective concentration for 50% inhibition of viral replication) in a nanomolar range. Furthermore, combined treatment of CA074-Me and GC373 in cells exhibited a strong synergistic activity against a feline coronavirus. These results indicate that these 3CL protease inhibitors have a potential to be developed as antiviral drugs for feline coronaviruses as a single agent or in combination with an entry blocker.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Compounds

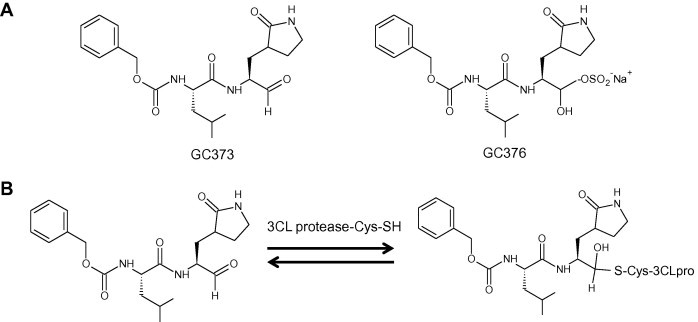

GC373 and GC376 compounds were synthesized as previously described (Tiew et al., 2011) (Fig. 1 ). Cathepsin B inhibitor CA074-Me [L-3-trans-((propylcarbamyl) oxirane-2-Carbonyl)-l-isoleucyl-l-proline methyl ester] and a pan-cysteine cathepsin inhibitor E64d [(2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methylbutane ethyl ester] were purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Fig. 1.

(A) Dipeptidyl protease inhibitors, GC373 and GC376. (B) Proposed mechanism of transition state inhibition of 3CL protease by GC373.

2.2. The expression and purification of transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) 3CL protease

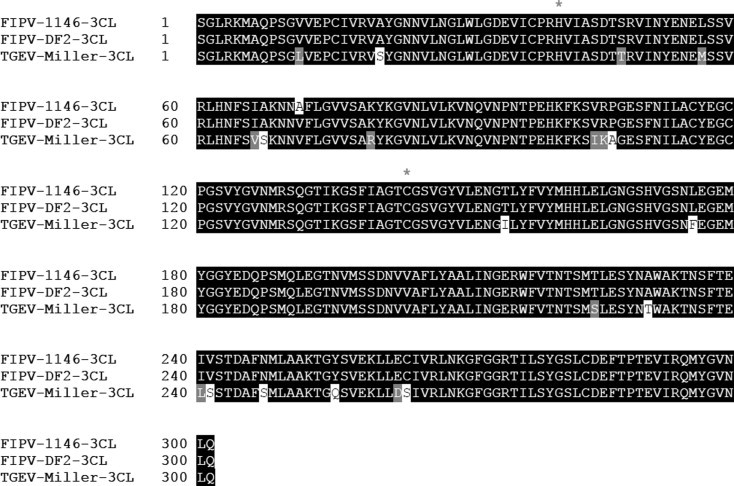

The 3CL proteases are highly conserved among all coronaviruses, and feline coronavirus 3CL protease is closely related to TGEV 3CL protease (Hegyi et al., 2002) (Fig. 2 ). Therefore, we cloned and expressed the TGEV 3CL protease for the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay. The cDNA encoding the full length of 3CL protease of TGEV Miller strain was amplified with RT-PCR as previously described (Anand et al., 2002). The primers contained the nucleotide sequence of the 3CL protease for cloning as well as the nucleotides for 6 Histidine in the forward primer. The forward and reverse primers were TGEVPro-6hisXba-F (tctagaaaggagatataccatgcatcatcatcatcatcattcaggtttacggaaaatggc) and TGEVPro-Xho-R(ctcgagtcactgaagatttacaccatac). The amplified product was subcloned to pET-28a(+) vector (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). The expression and purification of the 3CL protease was performed with a standard method described previously by our lab (Chang et al., 2012b, Takahashi et al., 2012, Tiew et al., 2011).

Fig. 2.

The sequence alignment of the 3CL protease of TGEV (Miller strain) and feline coronaviruses (WSU-1146 and DF2 strains). Asterisks mark the position of the conserved cysteine (144) and histidine (41) residues in the active site.

2.3. Enzymatic activity assay

3CL protease inhibitors, GC373 and GC376, and commercial cathepsin inhibitors, CA074-Me and E64d, were prepared in DMSO as stock solutions (10 mM), and further diluted in assay buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES, 0.4 mM EDTA, 30% glycerol, 120 mM NaCl, and 4 mM DTT at pH 6. TGEV 3CL protease at a final concentration of 0.1–0.2 μM and the substrate (Edans-Val-Asn-Ser-Thr-Leu-Gln/Ser-Gly-Leu-Arg-Lys[Dabcyl]-Met) (Kuo et al., 2004) at 10 μM were used for the studies. Compounds at various concentrations (0–50 μM) were pre-incubated with TGEV 3CL protease in 25 μl for 20 min at 37 °C, and the same volume of substrate was added to the mixture, or the compound was added to the protease immediately before the substrate was added to the enzyme/inhibitor mixture in 96-well black plate. The mixtures were then further incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and fluorescence readings were obtained on a microplate reader at 360 nm excitation and 480 nm emission wavelengths. The relative fluorescence units (RFU) were calculated by subtracting background (substrate control well without protease) from the fluorescence readings. The dose-dependent FRET inhibition curves were fitted with variable slope (four parameters) using GraphPad Prism software 5 (La Jolla, CA) in order to determine the compound concentration that gives a half-maximum response (IC50). In separate experiments, TGEV 3CL protease (0.2 μM) was incubated with serially diluted GC373 (0–2 μM) in 25 μl of assay buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min, followed by the addition of various concentrations of substrates (10–200 μM). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C, and fluorescence readings were obtained on a microplate reader at every 5 min for up to 30 min. The correction factors to compensate for the inner filter effects were determined empirically as described previously (Chang et al., 2012b, Cuerrier et al., 2005, Jaulent et al., 2007). The kinetic constant K m was determined by the fitting initial rates to the Michaelis–Menten equation using GraphPad Prism software. Lineweaver–Burk plots were constructed using GraphPad Prism software to determine K i values as well as the type of enzyme inhibition. Lastly, recovery of enzymatic activity of TGEV 3CL protease over time (rapid dilution experiments) was studied to demonstrate reversible binding of GC373 to TGEV 3CL protease (Copeland, 2005, Xie et al., 2011). Rapid dilution experiments were performed by incubating TGEV 3CL protease at 100 times the concentration that is normally used in a reaction with DMSO or GC373 at concentrations approximately 10 times greater than the IC50 value (10 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, the mixture was diluted 100-fold in reaction buffer to normal reaction condition before the substrate was added. The fluorescence readings were obtained on a microplate reader over time, and the progress curves were generated.

2.4. Cells, viruses, and reagents

Crandell Rees feline kidney (CRFK) cells were maintained in minimal essential medium containing 2–5% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (chlortetracycline [25 μg/ml], penicillin [250 U/ml], and streptomycin [250 μg/ml]). Cell culture-adapted feline coronaviruses WSU 79-1146 and WSU 79-1683 strains were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA).

2.5. Antiviral effects of the protease and cathepsin inhibitors against feline coronaviruses in cells

Virus infection was performed as follows: solvent (0.1% DMSO), CA074-Me, E64d, GC373 or GC376 was added at various concentrations to two-day old monolayers of CRFK cells prepared in 6 well plates. The cells were further incubated in the presence of each compound or solvent for 2 h at 37 °C, or the compound was added at the same time with virus inoculation. WSU-1147 or WSU-1683 was inoculated to the cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.05 or 5 (MOI 5 for Western blot analysis). The virus infected cells were incubated in the presence of a compound for up to 2 days, and EC50 was determined by the TCID50 method (Reed and Muench, 1938).

2.5.1. Western blot analysis

Cell lysates from CRFK cells were prepared by adding sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) sample buffer containing 2% β-mercaptoethanol and sonication for 20 s. The proteins were then resolved in a 10% Novex Bis-Glycin gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The transferred nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with primary antibodies to coronavirus nucleocapsid protein (Biocompare, Windham, NH) or β-actin as a loading control overnight, and then with the secondary antibodies conjugated with peroxidase for 2 h. Following incubation with a chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Pierce biotechnology, Rockford, IL), the signals were detected on X-ray films.

2.5.2. TCID50 method

A standard TCID50 method with the 10-fold dilution of each sample was used for virus titration (Reed and Muench, 1938).

2.5.3. Nonspecific cytotoxic effect

We determined the toxic concentration for 50% cell death (TC50) for each compound in CRFK cells. Confluent cells grown in 24-well plates were treated with various concentrations of compounds at up to 100 μM for cathepsin inhibitors and 500 μM for 3CL protease inhibitors for 24 or 48 h. Cell cytotoxicity was measured by a CytoTox 96® non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and crystal violet staining. The in vitro therapeutic index (TI) was calculated by dividing TC50 by EC50.

2.6. Combination treatment of a cathepsin B inhibitor, CA074-Me, and GC373

The CRFK cells were incubated with GC373 (0.02–0.2 μM), CA074-Me (0.5–5 μM), or the combinations of GC373 (0.02–0.2 μM) and CA074-Me (0.5–5 μM) for 2 h at 37 °C, prior to inoculation of WSU-1146 at an MOI of 0.05. After 24 h of incubation, virus replication was assessed with virus titration using the TCID50 method. Drug-drug interactions were analyzed by the three-dimensional model of Prichard and Shipman (Prichard and Shipman, 1990), using the MacSynergy II software at 95% confidence limits. Theoretical additive interactions were calculated from the dose–response curve for each compound individually, and the calculated additive surface was subtracted from the experimentally determined dose–response surface to give regions of synergistic or antagonistic interactions. The resulting surface appears as horizontal plane at 0% of synergy if the interactions of two compounds are additive. Any peak above or below this plane indicates synergy or antagonism, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of the 3CL protease inhibitors on the protease activity in the FRET-based assay

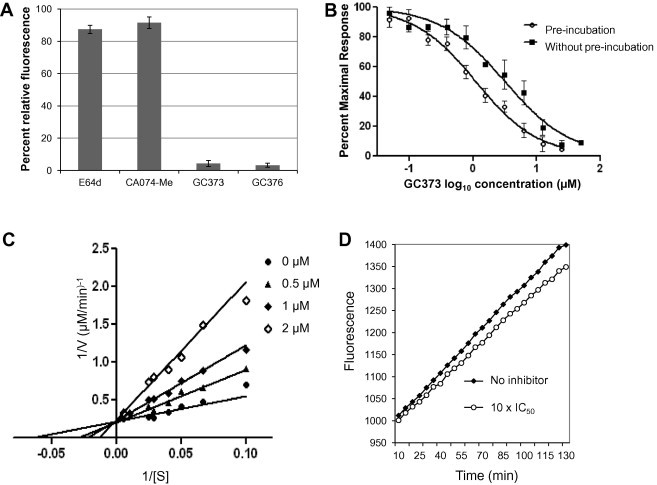

The protease inhibition assay was performed using the florescence substrate derived from a cleavage site of SARS-CoV to examine the inhibition of the 3CL protease by GC373 and GC376. The inhibitory effects of each compound at 50 μM (final concentration) on the activity of TGEV 3CL protease are shown in Fig. 3 A. Cathepsin B inhibitor CA074-Me and pan-cysteine cathepsin inhibitor E64d were included as controls. GC373 and GC376 remarkably inhibited the activity of TGEV 3CL protease at 50 μM, but the cathepsin inhibitors did not (Fig. 3A). The dose-dependent inhibition of TGEV 3CL protease activities by GC373 with or without pre-incubation of the compound with the protease is shown by open circles and filled squares, respectively, in Fig. 3B. The IC50 values of GC373 and GC376 against the 3CL protease determined in the FRET assay were 0.98 and 0.82 μM, respectively, when the compounds were pre-incubated with the protease. The IC50 values of GC373 and GC376 against the 3CL protease without pre-incubation were 3.2 and 2.7 μM, respectively, indicating that pre-incubation of the protease with the 3CL inhibitors caused about a 3-fold increase in inhibitor potency. The K m value for the fluorogenic substrate was 15.52 μM. The Lineweaver–Burk plots (Fig. 3C) suggested competitive inhibition of the proteolytic cleavage of the substrate by GC373 with a K i value of 0.43 ± 0.06 μM. Reversibility of our compound was determined by the rapid dilution experiments. As shown in Fig. 3D, the enzymatic activity of the 3CL protease incubated with GC373 at 10 × IC50 concentration recovered after 100-fold dilution of the protease/inhibitor mixture. At the final concentration after the dilution, the inhibitor concentration is 10-fold below the IC50. The recovery of enzymatic activity over time indicates that the compound was a reversible inhibitor.

Fig. 3.

FRET-based protease assay. (A) The effects of the 3CL protease inhibitors, GC373 and GC376, a cathepsin B inhibitor CA074-Me, and a pan-cysteine cathepsin inhibitor E64d on the activity of TGEV 3CL protease in the FRET-protease assay. TGEV 3CL protease was incubated with each compound at 50 μM for 20 min before the substrate was added to the mixture. Each bar represents the percent relative fluorescence (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (B) A plot of log10 GC373 concentration versus percent maximal response. TGEV 3CL protease was incubated with GC373 for 20 min at increasing concentrations prior to addition of substrate (open circles), or GC373 was added at the same time with the substrate (filled squares). The fluorescence signals were detected by a spectrophotometer, and the data are then plotted as percent maximal response against the log concentrations of the compound. The data points represent the percent maximal response (mean ± SEM). (C) Lineweaver–Burk plots of kinetic data of the TGEV 3CL protease incubated with various concentrations of GC373. The enzymatic activities were measured using 10–200 μM substrate in the absence (filled circles) or presence of 0.5 (filled triangles), 1 (filled diamonds), and 2 (open diamonds) μM GC373. (D) Progress curves for the recovery of enzymatic activities of TGEV 3CL protease after 3CL protease-GC373 complex was rapidly diluted to the normal assay solution. TGEV 3CL protease was incubated with DMSO (filled diamonds) or 10 μM (open circles) GC373 for 20 min, then rapidly diluted 100-fold in reaction buffer prior to substrate addition, and assayed for enzymatic activity.

3.2. Effects of the 3CL protease inhibitors and cathepsin inhibitors against the replication of feline coronaviruses in cells

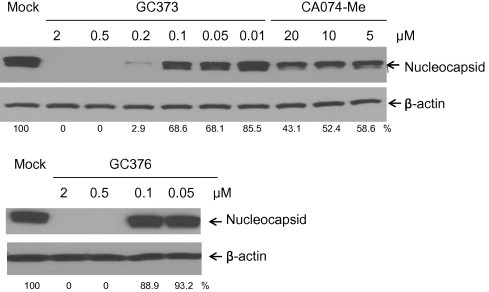

The antiviral effects of the 3CL protease inhibitors and cathepsin inhibitors were studied in cell culture. The replication of WSU-1683 and WSU-1146 were markedly inhibited by the presence of GC373, GC376, CA074-Me, or E64d (Table 1, Table 2 , Fig. 4 ). However, suppression of virus replication by the 3CL protease inhibitors was more potent than those by CA074-Me and E64d at 24 and 48 h, indicated by the EC50 values (Table 1). Notably, the antiviral activities of CA074-Me and E64d decreased substantially over time (Table 1). When the 3CL protease inhibitors were added to the cells at the same time of virus infection, the EC50 values of the compounds increased by 2- to 3.75-fold, compared to those obtained from pre-incubation of cells with the compounds (Table 2). The antiviral effects of the 3CL protease inhibitors were selective; they were not active against unrelated viruses such as influenza virus and porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus (data not shown). The antiviral activity of GC373 and GC376 was not due to nonspecific cytotoxicity since the 3CL protease inhibitors did not show any cytotoxicity, in various cells even at 500 μM. The cathepsin inhibitors CA074-Me and E64d also did not show any toxicity at 100 μM. The in vitro therapeutic indices calculated from the ratio of EC50/TC50 of cathepsin and 3CL protease inhibitors are at least 25 and 2900, respectively, at 24 h post virus infection. These results demonstrate that the replication of feline coronaviruses is effectively inhibited by the 3CL protease inhibitors with an excellent safety margin in cells.

Table 1.

The effects of GC373, GC376, CA074-Me and E64d on the replication of feline coronaviruses in CRFK cells pre-incubated with the compounds.

| Inhibition [EC50 (μM)] against feline coronaviruses⁎ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSU-1683 |

WSU-1146 |

|||

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| GC373 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.35 |

| GC376 | 0.17 ± 0.11 | 0.28 ± 0.10 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.10 |

| CA074-Me | 4.0 ± 0.71 | >10 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | >10 |

| E64d | 2.3 ± 0.28 | >10 | 1.45 ± 0.49 | >10 |

The mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of the EC50 values for virus inhibition at 24 and 48 h post infection are summarized. CRFK cells were incubated with each compound for 2 h before virus infection at an MOI of 0.05 and further incubated in the presence of each compound for up to 48 h. Virus titers were determined using the TCID50 method for the calculation of the EC50 values.

Table 2.

The effects of GC373 and GC376 on the replication of feline coronaviruses in CRFK cells without pre-incubation.

| Inhibition [EC50 (μM)] against feline coronaviruses ⁎ |

||

|---|---|---|

| WSU-1683 | WSU-1146 | |

| GC373 | 0.15 ± 0.18 | 0.12 ± 0.09 |

| GC376 | 0.40 ± 0.21 | 0.30 ± 0.14 |

The mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of the EC50 values for virus inhibition at 24 h post infection are summarized. Each compound was added to CRFK cells at the same time with virus inoculation at an MOI of 0.05, and further incubated in the presence of each compound for up to 24 h. Virus titers were determined using the TCID50 method for the calculation of the EC50 values.

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis of the effects of GC373, GC376, and CA074-Me on the accumulation of coronavirus nucleocapsid proteins in CRFK cells infected with WSU-1146. CRFK cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO, GC373, GC376, or CA074-Me for 2 h, followed by virus infection at an MOI of 5, and further incubated for 12 h. Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot for expression of coronavirus nucleocapsid protein and β-actin was loaded as an internal control. Numbers below each lane indicate the values of coronavirus nucleocapsid proteins normalized to β-actin obtained with densitometric scanning using TotalLab Quant software (TotalLab Ltd.).

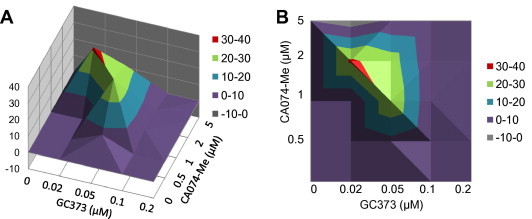

3.3. Effects of the combined treatment of GC373 and CA074-Me in the replication of WSU-1146

Combination treatment of GC373 and CA074-Me was performed to investigate the interactions of the two compounds with different modes of inhibition against the replication of WSU-1146. The effects of combination were determined to be strongly synergistic, as analyzed in a mathematical model based on the MacSynergy. Antiviral synergy was observed between GC373 and CA074-Me with an average Synergy95 volume of 99.3 μM2% at a 95% confidence interval over two experiments (Fig. 5 A and B, and Table 3 ). Absolute values over 25 μM2% indicate significant values of synergy. For example, when virus-infected CRFK cells were treated with GC373 at 0.05 μM or CA074-Me at 1 μM, each resulted in a 0.5 log10 reduction of virus titers; in contrast, the combination of the two led to a 2 log10 viral titer reduction, which was much more effective than either compound alone (indicated as synergy % in Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Three-dimensional plots showing the interaction of GC373 and CA074-Me on the replication of WSU-1146. (A and B) CRFK cells were incubated with CA074-Me (0.5–5 μM), GC373 (0.02–0.2 μM) or combinations of CA074-Me and GC373 for 2 h before the virus was inoculated in the cells at an MOI of 0.05. The cells were further incubated in the presence of each compound for 24 h, and virus replication was measured by the TCID50 method. Drug–drug interactions were analyzed by the three-dimensional model of Prichard and Shipman, using the MacSynergy II software at a 95% confidence interval. Surface above the plane of 0% synergy in the plot indicate synergy. (B) Contour plots (two-dimensional representations of the data) for easier identification of the concentration ranges where statistically significant synergistic or antagonistic effects occurred.

Table 3.

Summary of MacSynergy analysis on the combination effects of GC373 and CA074-Me against the replication of FIPV-1146 in CRFK cells.

| CA074-Me (μM) | GC373 (μM) |

Synergy volume at 95% CI (μM2%)⁎ | Antagonism volume at 95% CI (μM2%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |||

| 5 | 0 | −5.78 | 1.87 | 0 | −0.0004 | 99.3 | −5.79 |

| 2 | 0 | 31.45 | 25.23 | 1.94 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 28.95 | 2.56 | 0 | ||

| 0.5 | 0 | n/a | 7.28 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Synergy/antagonism volumes were calculated at the 95% confidence level.

4. Discussion

Feline infectious peritonitis is believed to be caused by infectious peritonitis virus arising by changing tissue tropism from intestinal cells to macrophages by mutations of feline enteric coronavirus in individual cats (Chang et al., 2012a, Vennema et al., 1998). The underlying mechanisms that allow the tissue tropism change is reported to be associated with mutations in the S and open reading frame 3c genes and the aberrant immune response of the host, but the detailed mechanism of the altered tropism has not been clearly established (Chang et al., 2012a, Chang et al., 2011, Pedersen et al., 2012, Poland et al., 1996, Vennema et al., 1998). The feline enteric coronaviruses are present ubiquitously in the environment and easily transmitted via a fecal-oral route. Thus elimination of feline coronavirus from multi-cat environments can be challenging. Although therapeutic measures for FIP are highly desirable to control this fatal disease, limited information on the effective treatment for FIP is available (Legendre and Bartges, 2009, Ritz et al., 2007). The general treatment options for FIP are supportive therapy, including the use of immunosuppressants such as glucocorticoids, and antibiotics (Hartmann and Ritz, 2008). Other agents that have been used include interferons, tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor, propentofylline, and polyprenyl immunostimulant (Ishida et al., 2004, Legendre and Bartges, 2009, Ritz et al., 2007). However, the therapeutic efficacy of those immune modulating agents was shown to be ineffective or needs further investigation in controlled trials (Fischer et al., 2011, Ritz et al., 2007). Ribavirin was reported to reduce the replication of FIPV with an IC50 of 10 μM and a TC50 of 69 μM, and a later study using specific pathogen free cats infected with FIPV showed that ribavirin treatment at 16.5 mg/kg was not effective at reducing fatality or severity of symptoms (Weiss et al., 1993). In addition, studies on the antiviral agents that directly or indirectly target virus components and/or replication steps are very limited (Barlough and Shacklett, 1994, Hsieh et al., 2010).

Our group has previously reported a series of new 3CL protease inhibitors targeting the 3CL protease of norovirus (Tiew et al., 2011). Coronavirus 3CL protease is classified as a chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease and shares a remarkable degree of conservation of the active site with norovirus 3CL protease. Our dipeptidyl 3CL protease inhibitors incorporate in their structure a glutamine surrogate and a leucine residue that correspond to the P1 and P2 sites in the substrate (Tiew et al., 2011). The amino acid residues in the substrate are designated as P1, P2, etc., starting at the scissile bond and counting towards the N-terminus. Likewise, the amino acid residues reside on the C-terminus side of the scissile bond are designated as P1′, P2′, etc (Schechter and Berger, 1967). The 3CL protease inhibitors were originally developed by our group by reflecting the substrate specificity of norovirus 3CL protease where the most frequently found residues in the P1 and P2 positions at the cleavage sites are glutamine and leucine, respectively. These amino acid residues in the P1 and P2 sites are also conserved among coronaviruses, including TGEV, FECV, FIPV, MHV, and human coronaviruses (Hegyi and Ziebuhr, 2002, Yang et al., 2005). These highly conserved features among viruses encoding containing 3C or 3CL proteases led to the finding that our dipeptidyl compounds potently inhibit the replication of noroviruses, picornaviruses, and coronaviruses including feline coronaviruses in cells (Kim et al., 2012). These peptidyl compounds were previously demonstrated to target coronavirus 3CL protease by the FRET protease assay and the crystal structure of TGEV 3CL protease-GC376 complex (Kim et al., 2012). GC373 possesses aldehyde as a potent electrophile that reacts with a cysteine (the nucleophilic sulfur) in the active site of virus protease in a reversible manner, and the bisulfite adduct warhead of GC376 was synthesized from the precursor aldehyde (Fig. 1). Since the bisulfite adduct is converted to the aldehyde form to form a covalent bond with cysteine in the active site of virus protease, based on the preliminary results in rats and the crystal structure of the complex of GC376 and TGEV 3CL protease, it is likely that GC376 behaves as a prodrug of the aldehyde counterpart (Kim et al., 2012).

In this study, we compared the antiviral activities of our dipeptidyl compounds and a cathepsin B inhibitor CA074-Me and non-specific cysteine cathepsin inhibitor E64d against feline coronaviruses WSU-1683 and WSU-1146. Both virus strains are cell culture adapted type II feline coronaviruses, of which WSU-1146 is confirmed to cause FIP in experimental settings (Pedersen et al., 1984b). WSU-1683 was originally thought to be a feline enteric coronavirus since it induced inapparent to mild enteritis without causing systemic infection in experimentally infected cats (Pedersen et al., 1984b). However, the subsequent sequence analysis studies on the mutations of genes that may contribute to development of FIPV from FECV suggest that WSU-1683 may have lost its virulence as FIPV and reverted to FECV biotype (Chang et al., 2010, Herrewegh et al., 1995, Pedersen, 2009; Pedersen et al., 2008). In our study, cathepsin inhibitors CA074-Me and E64d significantly inhibited the replication of feline coronaviruses at 24 h, although their potency was 13- to 100-fold lower than that of the 3CL protease inhibitors. However, a rapid loss of activity of CA074-Me and E64d was observed over time in cell culture without daily addition of the compounds, compared to the 3CL protease inhibitors. The shorter duration of the activity of cathepsin inhibitors against viral replication is speculated to be viruses overcoming the antiviral blockade imposed by inhibition of cathepsin activity by resynthesis of uninhibited cathepsins or the relative instability of the cathepsin inhibitors in media. The antiviral effects of non-specific cathepsin inhibition by E64d against feline coronaviruses were more potent than the inhibition by cathepsin B at 24 h post infection, which may be explained by differences in affinity for the protease, stability of compounds, or potential presence of cathepsins other than cathepsin B that are able to process the viral polyproteins. It was reported previously that FIPV and FECV differ in their requirement of cathepsins for the cleavage of S protein to gain entry into cells; both cathepsin B and L are required for FECV, but cathepsin L is dispensable for FIPV strains in cells (Regan et al., 2008), suggesting the different requirement for cathepsins among the virus strains. When our 3CL protease inhibitors were added to the cells at the same time of virus infection, the antiviral activity of the compounds was reduced, compared to 2 h pre-incubation of the cells with the inhibitors, reflected by the increase of the EC50 values by up to 3.7-fold. In the FRET assay, the IC50 values of GC373 and GC376 against the 3CL protease also increased by about 3-fold. However, the antiviral activities of GC373 and GC376 in cells were still potent with nanomolar EC50 values, even when the inhibitors were added to the cells at the time of virus inoculation.

Our X-ray crystallographic studies previously showed that GC376 binds to the active site and forms a reversible a covalent bond with a cysteine Cys residue in the active site of 3C or 3CL proteases of Norwalk virus, poliovirus, and TGEV (Kim et al., 2012). In this study, the kinetic analysis of TGEV 3CL protease and GC373 revealed the reversible, competitive nature of the inhibitor. We have not examined our 3CL protease inhibitors against the serotype I feline coronaviruses for their antiviral activities in this study. However we expect the 3CL protease inhibitors to be effective against serotype I feline coronaviruses since the 3CL protease is conserved among coronaviruses, and the 3CL protease inhibitors also inhibited the replication of TGEV and MHV in our previous study (Kim et al., 2012).

Since our 3CL protease inhibitors and CA074-Me act on different targets, we subsequently investigated the effects of the combined treatment of GC373 and CA074-Me against a feline coronavirus in cells. The analysis of the drug-drug combination at the 95% confidence interval by MacSynergy software showed the synergy volume of 99.3 μM2%. Only small volume of antagonism (−5.79 μM2%) was observed when a high concentration of CA074-Me (5 μM) were added to the cells containing GC373 (Fig. 5, Table 3). At high concentrations, synergic activity was reduced as the antiviral response by single treatment reached high, and the synergy was most evident at mid range of compound concentrations used. We found no significant synergy of drug cytotoxic effects at the concentrations used. Our results showed the entry blocker and the protease inhibitor that work at the different stages of virus life cycle act synergistically at the concentrations shown. The favorable drug–drug interactions observed with a feline coronavirus suggest a potential use of combination of compounds that target the host factor involved in virus entry and the virus protease for feline coronavirus infection.

In summary, the 3CL protease inhibitors used in this study were found to be highly effective against feline coronaviruses in cells and the antiviral effects of those 3CL protease inhibitors were more profound than inhibition of cathepsins. Strong synergic effects were observed in combination treatment of a cathepsin B inhibitor and our 3CL protease inhibitor. These findings underscore the effectiveness of our 3CL protease inhibitors for feline coronavirus infection and potential use of 3CL protease inhibitors as a single therapeutic agent or in combination with cathepsin B inhibitors.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI081891). The authors thank David George for technical assistance.

References

- Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. EMBO J. 2002;21:3213–3224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlough J.E., Shacklett B.L. Antiviral studies of feline infectious peritonitis virus in vitro. Vet. Rec. 1994;135:177–179. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.8.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetka V., Kubber-Heiss A., Kolodziejek J., Nowotny N., Hofmann-Parisot M., Mostl K. Prevalence of feline coronavirus types I and II in cats with histopathologically verified feline infectious peritonitis. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;99:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.W., de Groot R.J., Egberink H.F., Rottier J.M. Feline infectious peritonitis: insights into feline coronavirus pathobiogenesis and epidemiology based on genetic analysis of the viral 3c gene. J. Gen. Virology. 2010;91:415–420. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.W., Egberink H.F., Rottier P.J. Sequence analysis of feline coronaviruses and the circulating virulent/avirulent theory. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:744–746. doi: 10.3201/eid1704.102027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.W., Egberink H.F., Halpin R., Spiro D.J., Rottier P.J. Spike protein fusion peptide and feline coronavirus virulence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:1089–1095. doi: 10.3201/eid1807.120143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K.O., Takahashi D., Prakash O., Kim Y. Characterization and inhibition of norovirus proteases of genogroups I and II using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay. Virology. 2012;423:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland R.A. first ed. Wiley-Interscience; 2005. Evaluation of Enzyme Inhibitors in Drug Discovery: a Guide for Medicinal Chemists and Pharmacologists (Methods of Biochemical Analysis) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuerrier D., Moldoveanu T., Davies P.L. Determination of peptide substrate specificity for mu-calpain by a peptide library-based approach: the importance of primed side interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40632–40641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506870200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Y., Ritz S., Weber K., Sauter-Louis C., Hartmann K. Randomized, placebo controlled study of the effect of propentofylline on survival time and quality of life of cats with feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011;25:1270–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann K., Ritz S. Treatment of cats with feline infectious peritonitis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008;123:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeney J.L., Evermann J.F., McKeirnan A.J., Marker-Kraus L., Roelke M.E., Bush M., Wildt D.E., Meltzer D.G., Colly L., Lukas J. Prevalence and implications of feline coronavirus infections of captive and free-ranging cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) J. Virol. 1990;64:1964–1972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1964-1972.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi A., Ziebuhr J. Conservation of substrate specificities among coronavirus main proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:595–599. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi A., Friebe A., Gorbalenya A.E., Ziebuhr J. Mutational analysis of the active centre of coronavirus 3C-like proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:581–593. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh A.A., Vennema H., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J., de Groot R.J. The molecular genetics of feline coronaviruses: comparative sequence analysis of the ORF7a/7b transcription unit of different biotypes. Virology. 1995;212:622–631. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh A.A., Smeenk I., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J., de Groot R.J. Feline coronavirus type II strains 79–1683 and 79–1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. J. Virol. 1998;72:4508–4514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4508-4514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homes K.V. Coronaviruses. In: Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., editors. Fields Virology. third ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 1187–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh L.E., Lin C.N., Su B.L., Jan T.R., Chen C.M., Wang C.H., Lin D.S., Lin C.T., Chueh L.L. Synergistic antiviral effect of Galanthus nivalis agglutinin and nelfinavir against feline coronavirus. Antiviral Res. 2010;88:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T., Shibanai A., Tanaka S., Uchida K., Mochizuki M. Use of recombinant feline interferon and glucocorticoid in the treatment of feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2004;6:107–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaulent A.M., Fahy A.S., Knox S.R., Birtley J.R., Roque-Rosell N., Curry S., Leatherbarrow R.J. A continuous assay for foot-and-mouth disease virus 3C protease activity. Anal. Biochem. 2007;368:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M., Citino S., McNabb A.H., Moffatt A.S., Gertz K., Kania S. Detection of feline coronavirus in captive Felidae in the USA. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2002;14:520–522. doi: 10.1177/104063870201400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Lovell S., Tiew K., Mandadapu S.R., Alliston K.R., Battaile K.P., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O. Broad-Spectrum Antivirals against 3C or 3C-like proteases of picornaviruses, noroviruses and coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2012;86:11754–11762. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummrow M., Meli M.L., Haessig M., Goenczi E., Poland A., Pedersen N.C., Hofmann-Lehmann R., Lutz H. Feline coronavirus serotypes 1 and 2: seroprevalence and association with disease in Switzerland. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005;12:1209–1215. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.10.1209-1215.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C.J., Chi Y.H., Hsu J.T., Liang P.H. Characterization of SARS main protease and inhibitor assay using a fluorogenic substrate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318:862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre A.M., Bartges J.W. Effect of polyprenyl immunostimulant on the survival times of three cats with the dry form of feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009;11:624–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motokawa K., Hohdatsu T., Hashimoto H., Koyama H. Comparison of the amino acid sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the peplomer, integral membrane and nucleocapsid proteins of feline, canine and porcine coronaviruses. Microbiol. Immunol. 1996;40:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963–2008. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009;11:225–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Black J.W., Boyle J.F., Evermann J.F., McKeirnan A.J., Ott R.L. Pathogenic differences between various feline coronavirus isolates. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1984;173:365–380. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9373-7_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Evermann J.F., McKeirnan A.J., Ott R.L. Pathogenicity studies of feline coronavirus isolates 79–1146 and 79–1683. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1984;45:2580–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Allen C.E., Lyons L.A. Pathogenesis of feline enteric coronavirus infection. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2008;10:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Liu H., Scarlett J., Leutenegger C.M., Golovko L., Kennedy H., Kamal F.M. Feline infectious peritonitis: role of the feline coronavirus 3c gene in intestinal tropism and pathogenicity based upon isolates from resident and adopted shelter cats. Virus Res. 2012;165:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland A.M., Vennema H., Foley J.E., Pedersen N.C. Two related strains of feline infectious peritonitis virus isolated from immunocompromised cats infected with a feline enteric coronavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:3180–3184. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3180-3184.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard M.N., Shipman C., Jr. A three-dimensional model to analyze drug-drug interactions. Antiviral Res. 1990;14:181–205. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(90)90001-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z., Hingley S.T., Simmons G., Yu C., Das Sarma J., Bates P., Weiss S.R. Endosomal proteolysis by cathepsins is necessary for murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus type 2 spike-mediated entry. J. Virol. 2006;80:5768–5776. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00442-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Regan A.D., Shraybman R., Cohen R.D., Whittaker G.R. Differential role for low pH and cathepsin-mediated cleavage of the viral spike protein during entry of serotype II feline coronaviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2008;132:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz S., Egberink H., Hartmann K. Effect of feline interferon-omega on the survival time and quality of life of cats with feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2007;21:1193–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2007.tb01937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter I., Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons G., Gosalia D.N., Rennekamp A.J., Reeves J.D., Diamond S.L., Bates P. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11876–11881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505577102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi D., Kim Y., Chang K.O., Anbanandam A., Prakash O. Backbone and side-chain (1)H, (15)N, and (13)C resonance assignments of Norwalk virus protease. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2012;85:12570–12577. doi: 10.1007/s12104-011-9316-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiew K.C., He G., Aravapalli S., Mandadapu S.R., Gunnam M.R., Alliston K.R., Lushington G.H., Kim Y., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of inhibitors of Norwalk virus 3C protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:5315–5319. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennema H., Poland A., Foley J., Pedersen N.C. Feline infectious peritonitis viruses arise by mutation from endemic feline enteric coronaviruses. Virology. 1998;243:150–157. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel L., Van der Lubben M., te Lintelo E.G., Bekker C.P., Geerts T., Schuijff L.S., Grinwis G.C., Egberink H.F., Rottier P.J. Pathogenic characteristics of persistent feline enteric coronavirus infection in cats. Vet. Res. 2010;41:71. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R.C., Cox N.R., Martinez M.L. Evaluation of free or liposome-encapsulated ribavirin for antiviral therapy of experimentally induced feline infectious peritonitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 1993;55:162–172. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(93)90076-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., Lin L., Tong L., Jiang Y., Zheng M., Chen Z., Jiang X., Zhang X., Ren X., Qu W., Yang Y., Wan H., Chen Y., Zuo J., Jiang H., Geng M., Ding J. AST1306, a novel irreversible inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor 1 and 2, exhibits antitumor activity both in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Xie W., Xue X., Yang K., Ma J., Liang W., Zhao Q., Zhou Z., Pei D., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R., Yuen K.Y., Wong L., Gao G., Chen S., Chen Z., Ma D., Bartlam M., Rao Z. Design of wide-spectrum inhibitors targeting coronavirus main proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr J., Snijder E.J., Gorbalenya A.E. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J. Gen. Virol. 2000;81:853–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]