Abstract

Introduction

CD47 is a ubiquitously expressed cell surface receptor that serves as a counter-receptor for SIRPα in recognition of self by the innate immune system. Independently, CD47 also functions as an important signaling receptor for regulating cell responses to stress.

Areas covered

We review the expression, molecular interactions, and pathophysiological functions of CD47 in the cardiovascular and immune systems. CD47 was first identified as a potential tumor marker, and we examine recent evidence that its dysregulation contributes to cancer progression and evasion of anti-tumor immunity. We further discuss therapeutic strategies for enhancing or inhibiting CD47 signaling and applications of such agents in preclinical models of ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion injuries, organ transplantation, pulmonary hypertension, radioprotection, and cancer.

Expert opinion

Ongoing studies are revealing a central role of CD47 for conveying signals from the extracellular microenvironment that limit cell and tissue survival upon exposure to various types of stress. Based on this key function, therapeutics targeting CD47 or its ligands thrombospondin-1 and SIRPα could have broad applications spanning reconstructive surgery, engineering of tissues and biocompatible surfaces, vascular diseases, diabetes, organ transplantation, radiation injuries, inflammatory diseases, and cancer.

Keywords: autophagy, cancer immunotherapy, ischemia, macrophages, nitric oxide, ionizing radiation, reperfusion injury, thrombospondin-1, tissue perfusion

1. Introduction

CD47, also known as integrin-associated protein and Rh-related antigen, was first identified as a protein that is lost from red blood cells (RBC) of patients with Rh-null hemolytic anemia [1]. Independently, the same protein was isolated based on its co-purification with the integrin αvβ3 and as the antigen recognized by a group of monoclonal antibodies that differentially recognize ovarian carcinoma versus nonmalignant ovarian tissue [2]. Immunochemical characterization and genomic mapping studies established identity between these proteins [3]. CD47 is now recognized as a widely expressed cell surface protein in higher vertebrates. Although elevated expression of CD47 in certain human cancers was reported beginning in 1986 [2, 4], recognition of its widespread expression on normal cells led to decreased interest in CD47 as a tumor antigen. Meanwhile, research efforts focused in defining functions of CD47 mediated by its lateral interactions with the Rh complex in erythrocytes and with certain integrins and cytoplasmic signaling molecules in other cells, its interactions with the secreted protein thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), and its role as a counter-receptor for two members of the signal regulatory protein (SIRP) receptor family.

Two major functions of CD47 are now recognized. Interaction of CD47 with SIRPα on phagocytic cells conveys a “don’t eat me” signal that limits clearance of circulating RBC expressing more than a required minimum density of CD47 [5]. Cells that display lower levels or chemically modified forms of CD47 are primed for removal [6, 7], whereas malignant cells expressing elevated levels of CD47 are resistant to clearance despite expressing other markers recognized by M1 polarized macrophages [8]. The second major function of CD47 is as a signaling receptor. Upon binding to TSP1, CD47 transduces signals that alter cellular calcium, cyclic nucleotide, integrin, and growth factor signaling and control cell fate, viability, and resistance to stress [9]. The latter function has been key to understanding how targeting CD47 could provide therapeutic benefits in a variety of major diseases including cardiovascular diseases and cancer. Here we review preclinical studies that support the rapidly expanding interest in CD47 as a therapeutic target and review strategies to regulate its function.

2. CD47 expression and regulation

CD47 is widely expressed on the plasma membrane as several glycosylated isoforms including 40–55 kDa isoforms modified by N-glycosylation and >200 kDa isoforms that contain glycosaminoglycan modifications at serines 64 and 79 [10]. Lower mass isoforms of CD47 have been reported that result from proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular domain [11, 12]. Alternative splicing of the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of CD47 provides an additional level of regulation [2, 13].

CD47 expression is elevated in several human cancers, and high expression can be a diagnostic marker and negative prognostic indicator [4, 14–19]. Based on a similar elevation observed on hematopoietic stem cells, high CD47 expression was proposed to be a cancer stem cell marker that protects these cells from phagocytic clearance [20]. CD47 mRNA and protein expression is elevated in lungs from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension [21] and in a preclinical model of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) [22]. In vitro studies suggested that this results from induction of CD47 by hypoxia, which requires TSP1 [21]. Conversely, CD47 expression is decreased on aged RBC and is one of several senescence markers that promote their phagocytic clearance [23, 24]. Notably, CD47 expression on RBC of pediatric sickle cell patients was increased following treatment with hydroxyurea [25].

The molecular regulation of CD47 expression remains poorly understood. Studies using a −232 to −12 CD47 promoter-reporter construct identified a positive role for the transcription factorα-Pal/NRF-1. This pathway regulates CD47-dependent neurite outgrowth from neuroblastoma cells [26]. Recently miR-133a was identified as a negative regulator of CD47 expression via interactions with the 3′-untranslated region of its mRNA [19].

CD47 expression is also subject to post-translational regulation. Hyperglycemia inhibits the matrix metalloprotease-2-dependent cleavage of CD47 on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) [11]. This cleavage in the extracellular domain prevents SIRPα binding and signaling.

3. CD47 interactions and signaling

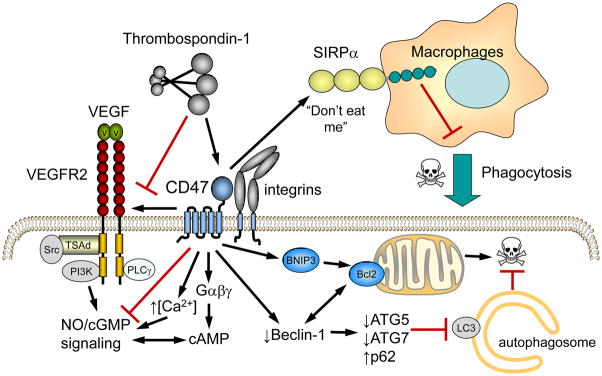

Known interactions between CD47 and other proteins are summarized in Fig. 1. Several of these interactions have functional consequences for signal transduction. CD47 exposes only two short loops connecting its membrane spanning segments and a variably spliced C-terminal tail to the cytoplasm, so only limited direct interactions between CD47 and cytoplasmic signaling proteins are expected. Instead, lateral interactions with other transmembrane proteins that engage more extensive signaling networks may play a dominant role in transducing CD47 signals. CD47 associates laterally with αvβ3 and several other integrins [2]. Ligation of CD47 induces activation of these integrins and consequently can alter αvβ3 integrin signaling targets such as focal adhesion kinase and paxillin [27]. The CD47/integrin complex associates with some heterotrimeric G proteins, possibly via PLIC-1 [28], which play a role in regulation of cAMP signaling by CD47 [29–31].

Fig. 1. CD47 interacting partners.

On most cell types CD47 laterally associates with β3 integrins and certain β1 integrins. RBC lack integrins, and CD47 instead associates with the Rh antigen complex, which links CD47 to the cytoskeleton via ankyrin and spectrin. Additional cell type-specific lateral interactions of CD47 have been identified involving SIRPα, VEGFR2, and the Fas receptor. Cytoplasmic binding partners include PLIC1, which in turn binds to Gβγ, and BNIP3.

Ligation of CD47 can induce cell death, which may be mediated by Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kD-interacting protein (BNIP3). The transmembrane domain and C-terminal tail of CD47 were used as bait for yeast two-hybrid screening of a human lymphocyte cDNA library and identified BNIP3 as a binding partner [32]. Binding to CD47 requires the transmembrane domain of BNIP3, implying a lateral interaction, although deletion of other BNIP3 domains also diminishes binding. Antisense suppression of BNIP3 blocks CD47-mediated cell death, whereas activation of CD47 using a TSP1 peptide induces translocation of BNIP3 to mitochondria (Fig. 2). Insertion of the BNIP3 transmembrane domain into the mitochondrial membrane triggers opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and release of cytochrome c, leading to cell death [33]. CD47 ligation also stimulates recruitment of Drp1 to mitochondria, but this has not been shown to involve any direct interaction between CD47 and Drp1 [34].

Fig. 2. CD47 signal transduction.

Engagement of CD47 by TSP1 inhibits its lateral interaction with VEGFR2 and modulates signaling mediated by Ca2+, cGMP, and cAMP in vascular cells. CD47 ligation also controls cell survival via mitochondrial dependent pathways mediated by translocation of BNIP3 and suppression of a protective autophagy pathway that blocks apoptosis. CD47 also serves as the counter-receptor for SIRPα. Engagement of SIRPα on phagocytic cells suppresses phagocytic killing of target cells.

Based on co-immunoprecipitation and fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies, VEGFR2 is another proximal lateral binding partner of CD47 [35]. CD47 constitutively associates with VEGFR2 in endothelial cells, and ligation of CD47 by TSP1 and VEGFR2 by VEGF dissociates this complex and inhibits VEGFR2 signaling (Fig. 2).

The NO/cGMP cascade is a major physiological signaling target of CD47 in endothelial cells, VSMC, and platelets (Fig. 2). CD47 signaling redundantly inhibits this pathway. Ligation of CD47 by TSP1 prevents VEGFR2 autophosphorylation and downstream activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) via Akt-mediated phosphorylation. Independently, CD47 inhibits Ca2+/calmodulin-mediated activation of eNOS [36], activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) by nitric oxide (NO), the NO precursor nitrite [37] and some drugs [38–40], and downstream activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase by cGMP [41]. Consequently, conditions such as aging where levels of the CD47 ligand TSP1 are elevated are associated with decreased tissue levels of cGMP and NO [42, 43]. In addition to direct effects on the NO/cGMP pathway, some cAMP phosphodiesterases are regulated by cGMP, so altered cGMP levels provide a second mechanism by which CD47 ligation can influence cAMP signaling [44].

Contrary to the induction of apoptosis and type III programmed cell death by CD47 ligation, gene knockout or pharmacologic blocking of CD47 confers increased cell survival of stress including that caused by ionizing radiation [45, 46]. Although elevated NO/cGMP signaling has known pro-survival roles, the protection from radiation induced death by CD47 blockade was not reproduced when NO or cGMP levels were pharmacologically enhanced, and blockade of NO synthesis did not impair radioprotection by CD47 blockade [46]. This finding led to a search for alternate mechanisms through which CD47 could control cell survival, which identified a major role for autophagy (Fig. 2) [47]. Irradiated cells lacking CD47 exhibit increased formation of autophagosomes. Irradiation selectively increases beclin-1, ATG5, ATG7 and reduces p62/sequestosome expression in CD47-null cells. Blockade of CD47 in combination with total body irradiation similarly increases autophagy gene expression in mouse lung while suppressing apoptosis in the same tissue. Inhibition of autophagy selectively sensitizes CD47-deficient cells to radiation, indicating that enhanced autophagy is necessary for the prosurvival response to CD47 blockade. Moreover, re-expression of CD47 in CD47-deficient T cells sensitizes these cells to death by ionizing radiation and reverses the increase in autophagic flux associated with survival. Therefore, CD47 deficiency confers cell survival through the activation of a protective autophagic flux. Beclin-1 also functions as a gatekeeper of apoptosis via its interaction with Bcl-2 [48]. Thus, regulation of beclin-1 downstream of CD47 may control a cell fate decision to initiate a protective autophagy response while suppressing apoptotic programmed cell death.

4. CD47 in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology

The role of CD47 in vascular and cardiac health and disease is increasingly being appreciated. This arises from the central role CD47 plays in mediating the redundant and potent inhibition of NO signaling by TSP1. NO promotes blood flow and regulates blood pressure through several concurrent mechanism including suppressing activation of arterial endothelial cells to decrease expression of adhesion molecules, limiting of platelet aggregation to prevent thrombosis, altering calcium levels in arterial VSMC leading to arterial dilation to increase blood flow and lower blood pressure, and modulating cardiac responses to vasoactive agents [49, 50].

4.1. CD47 vascular expression

CD47 is expressed on the surface of all vascular cells, but expression on RBC decreases as the cells age. The resulting loss of inhibitory signaling through SIRPα leads to accelerated clearance by splenic macrophages [7, 23]. However, in the general circulation this process appears to be mediated by Fc-gamma receptors [24]. Platelets are another important vascular cell type that expresses CD47 [51], and expression levels can vary with activation [52] and disease [53]. CD47 expression is found in systemic [35] and pulmonary arterial endothelial cells [21] and systemic VSMC [35, 54]. In pulmonary arterial endothelial cells, hypoxia-mediated induction of CD47 is decreased in cells lacking TSP1 [21], suggesting concordant gene regulation of the ligand and receptor. CD47 expression is up-regulated in arterial endothelial cells under non-laminar flow conditions [55], implying a link to atherosclerosis. In healthy non-human primate arteries, CD47 expression is limited to the endothelium, but mechanical injury up-regulates CD47 expression in both endothelial and VSMC compartments [56]. The possibility that expression of CD47 is altered in diseased human arteries has not been examined. Finally, elevated glucose preserves functional CD47 on the surface of human VSMC by limiting enzymatic cleavage of its globular domain [11]. This is important because TSP1 requires this region of CD47 to activate signaling [10, 57].

4.2. CD47 control of angiogenesis and wound healing

Angiogenesis involves coordinated responses of several cell types to establish new blood flow to meet metabolic demands. This is initiated by endothelial cells that move beyond existing vascular channels to establish new vessels. CD47-binding agents including TSP1 and TSP1 peptides inhibit the angiogenic activities of endothelial cells in vitro and FGF2-stimulated angiogenesis in mouse cornea [58]. By activating CD47 on arterial and pulmonary endothelial cells, TSP1 limits angiogenesis by inhibiting endogenous NO production [36], NO-mediated activation of sGC [38], and VEGF-mediated activation of endothelial cell NO production through CD47 binding to VEGFR2 [35]. The net result of these redundant effects is a marked inhibition of angiogenesis in muscle tissues explants [37, 59] and in full thickness skin grafts [60].

4.3. CD47 control of arterial tone and blood flow

Wound healing requires adequate tissue perfusion and blood flow [61]. Normal laminar blood flow enhances vascular NO production and decreases vascular inflammation and adhesion, whereas turbulent blood flow suppresses endogenous NO production and up-regulates adhesive proteins that recruit inflammatory cells [49]. Consistent with a role in promoting vascular inflammation and adhesion of circulating vascular cells, a CD47 targeting peptide increased cell adhesion molecule expression on brain microvascular endothelial cells [62]. CD47 also acutely controls tissue blood flow in cutaneous vascular beds [43], skeletal muscles [9], and visceral organs [22, 63]. In the absence of CD47 or TSP1, tissue blood flow increases more in response to a systemic administration of vasodilators or following ischemic challenge [37, 64, 65].

4.4. CD47 in aging and dietary vasculopathy

The regulation of CD47 is currently being explored in conditions associated with chronic loss of tissue perfusion and blood flow such as diabetes and advanced age. High glucose elevates TSP1 secretion by cultured VSMC and promotes sensitivity to insulin-like growth factor-1 via CD47 [66], suggesting that uncontrolled diabetes enhances CD47 signaling. It remains to be determined if CD47 is up-regulated in diabetes and if blocking CD47 increases tissue blood flow or decreases VSMC proliferation. Age-induced up-regulation of cutaneous CD47 correlates with a dramatic loss of skin blood flow [43]. Conversely, the absence of CD47 preserves tissue perfusion and sensitivity to vasoactive agents in aged mice [42].

4.5. CD47 in ischemia and ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)

Ischemia, the fixed loss of blood flow and perfusion, is compounded by the process of reperfusion, and IRI is a major contributor to myocardial infarction, stroke, and organ transplant failure. Lack of CD47 confers protection to IRI in soft tissues [67] and in several visceral organs including liver [63] and kidney [22]. The reasons for tissue protection include enhanced blood flow, decreased inflammatory cell recruitment, and decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. In chimeric CD47 null mice transplanted with CD47-positive wild type bone marrow, renal IRI remains dramatically abrogated [22]. These data suggest that parenchymal CD47, as opposed to circulating cell CD47, is responsible for promoting IRI.

4.6. CD47 as a regulator of blood pressure

Blood pressure is maintained through a balance among local, regional and systemic factors [68, 69]. NO and VEGF, via its ability to also stimulate NO production in endothelial cells, dilates resistance arteries to lower blood pressure [70, 71]. At rest, animals lacking CD47 demonstrate significantly lower mean, systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared to controls. CD47- and TSP1-null mice display greater decreases in blood pressure in response to challenge with a vasodilator or to sympathetic nerve blockade [36, 72]. Conversely, treatment of wild type and TSP1-null with but not CD47-null mice with intravenous TSP1 or a CD47 antibody that selectively acts as an agonist in vivo acutely elevates blood pressure [36]. Thus, plasma TSP1, through engaging vascular cell CD47, is a hypertensive agent and supports blood pressure through inhibition of NO, cGMP and VEGFR2 signaling. Furthermore, TSP1 inhibits cAMP-mediated vasodilation of arteries, which likely occurs through CD47 activation on VSMC and suggests yet another mechanism through which CD47 controls blood pressure [44].

4.7. CD47 and the heart

The absence of cardiac CD47 in healthy mice is associated with enhanced cardiac output after vasoactive challenge with exogenous NO [72]. However, the role of cardiac CD47 in disease is not determined. New data in hypoxia-mediated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) demonstrates induction of pulmonary CD47 and TSP1 in human disease and in multiple preclinical models of PAH [21]. TSP1-null mice, which lack the ability to activate CD47, are protected from developing the clinical manifestations of PAH including cardiac hypertrophy, and increased right ventricular and pulmonary artery pressures [21, 73]. Together these data suggest that TSP1-CD47 signaling promotes PAH and right heart failure. Finally, TSP1 expression was enhanced after transverse aortic constriction [74], though it is not known if TSP1-CD47 signaling promotes left heart failure.

5. CD47 in immunology

5.1. CD47 in leukocyte migration

Leukocyte migration plays important roles in innate and adaptive immune function. The increased susceptibility of CD47-null mice to intraperitoneal E. coli infection is associated with defective neutrophil transendothelial migration [75]. Similar roles for CD47 were found in other bacterial and viral infections [76]. Transendothelial migration of neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells is limited in CD47 null mice, and the failure of wild type bone marrow to correct this defect suggested that CD47 on endothelium is important for leukocyte egress [77]. Binding of the human CD47 function blocking antibody B6H12 to endothelial cells induces cytoskeletal remodeling and up-regulates Src and Pyk2 tyrosine kinase, increasing tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin, an inducer of cell adhesion. Thus, endothelial cell CD47 is important for leukocyte recruitment during the course of infection.

Migration of leukocytes is also regulated by CD47. PMN treated with CD47 blocking antibodies or isolated from CD47 null mice show defects in cell migration and stimulation by a TLR2/6 agonist [78]. CD47-deficient dendritic cells also exhibit migration defects [79], and a CD47 blocking antibody inhibits TSP1 induced T cell chemotaxis mediated by α4β1 integrin [80]. Therefore, CD47 plays multiple roles in leukocyte migration, and total therapeutic blockade of CD47 would thus be expected to compromise immunity.

5.2. CD47 in innate immune effector function

The interaction between CD47 on target cells and SIRP-α on phagocytes is a potent inhibitor of phagocytosis and serves as a species-specific self-recognition mechanism [81]. Wild type mice rapidly eliminate CD47-deficient RBC, T cells, and bone marrow independent of antibody or complement stimulation [6, 82]. Similarly, clearance of transfused porcine RBC in mice depends on the species specificity of CD47-SIRPα binding [83], and expression of human CD47 on porcine RBC suppresses their phagocytosis by human macrophages [84]. The density of CD47 on target cells is critical for this negative regulation of phagocytosis [5], and consequently tumor cells with elevated CD47 expression are more resistant to being cleared by phagocytosis.

CD47 may also have an indirect role in regulating phagocytosis because macrophages of chimeric mice lacking CD47 on nonhematopoietic cells are tolerant towards some CD47 null target cells [85]. The role of CD47 in phagocytosis is further complicated by a recent report that certain modified forms of CD47 promote rather than inhibit phagocytosis [7].

CD47 also regulates NK effector function. Elevated CD47 expression on target tumor cells inhibits nonphagocytic killing by NK cells [86]. None phagocytic antibody-dependent target cell killing by neutrophils is similarly inhibited by target cell CD47 expression [87, 88].

5.3. CD47 and T cell activation

The best-characterized T cell coactivator is CD28, but CD47 ligation by certain antibodies or by TSP1 peptides can have similar effects on T cell activation and proliferation [89–91]. This costimulation involves activation of Ras, JNK, ERK1, Elk1, and AP1 and may be mediated by CD47 functioning as an integrin activator to promote T cell spreading [90, 92, 93]. In contrast to these costimulatory activities, the CD47 ligand TSP1 inhibits CD3-dependent T cell activation independent of β1 integrins but dependent on expression and glycosaminoglycan modification of CD47 [10, 80, 91]. CD47 on antigen presenting cells (APC) may play an additional stimulatory role in T cell activation. Binding of CD47 expressed on APC to SIRPγ on T cells results in enhanced antigen-specific T cell proliferation [94].

5.4. T cell differentiation

CD4+ T cells differentiate into several lineages in response to specific environmental cytokines and signals from APC [95]. CD47 regulates this process on both APC and T cells. CD47-Fc inhibits IL-12, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 production in endotoxin-primed immature dendritic cells and, thus, inhibits their functional maturation [96]. Ligation of SIRPα or CD47 also caused a decrease in anti-CD3-activated T cell IL-12 responsiveness as measured by IFN-γ production. These findings clearly demonstrate the inhibitory effects of CD47 through antibody and SIRPα ligation on the priming of T cells. CD47 is also a negative regulator of Th1 lineage differentiation [97]. The CD47 antibody B6H12, which blocks both TSP1 and SIRPα binding, inhibited the development of Th1 cells and down-regulated production of IFN-γ [97]. CD47-null mice on a Th2-prone BALB/c background developed Th1-biased cellular and humoral responses [98]. This bias is consistent with the exaggerated contact hypersensitivity response in CD47 deficient mice [98, 99]. In addition to effects on T cell polarization, however, TSP1 null mice show a similar hypersensitivity response, which was attributed to a deficiency in CD47-mediated T cell apoptosis [99].

6. CD47 in cancer

Dysregulation of CD47 in cancer first became apparent when it was identified as the ovarian tumor marker OA3 and later found to be a pan-ovarian carcinoma antigen [4]. Elevated CD47 expression was subsequently reported in a variety of cancers including renal [16] and prostate carcinoma [100], multiple myeloma, [101], T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [102], oral squamous cell carcinoma [103], human acute myeloid leukemia-associated leukemia stem cells [17], CD44+ tumor initiating bladder carcinoma cells [104], and glioma and glioblastoma [18].

6.1. CD47 Expression in Cancer

Altered CD47 expression in cancer is not limited to tumor cells and can play a critical role in the tumor microenvironment. Increased expression of CD47 in the bone marrow is correlated with poor prognosis of breast cancer patients [105]. This also correlated with SIRPα expression, indicating that active SIRPα/CD47 interactions involving circulating cells promote tumor progression by allowing the cancer cells escape immunosurveillance [106]. Bone-marrow derived hematopoietic progenitor cells are essential in the formation of niches that stimulate tumor formation and metastasis [107]. In a murine model of metastasis to bone, tumor burden was decreased in CD47-deficient mice when compared to wild-type. CD47 null mice exhibited decreased tumor-mediated bone destruction, associated with an NO mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis, leading to decreased tumor metastasis to bone [107].

6.2. CD47 and anti-tumor immunity

One major function proposed for CD47 is to limit innate anti-tumor immunity. Elevated expression of CD47 was first associated with escape of host anti-tumor immunity for head and neck squamous carcinoma, where natural killer tumor cell cytotoxicity was inhibited by high CD47 expression on the target cells [86]. CD47 activation on immune cells by TSP1 controls inflammatory responses including activation and migration of innate and adaptive immune cells [75, 78, 80, 91]. Suppression of CD47 or increased TSP1 expression was associated with an increased density of tumor-associated macrophages that may be cytotoxic to the tumor [46, 108]. Several studies demonstrate that CD47 blockade using specific antibodies increases macrophage mediated phagocytosis of leukemia and solid tumor cells in vitro and in mouse models [109]. This is proposed to involve inhibition of tumor cell phagocytosis by engaging SIRPα on tumor-associated macrophages, indicating that tumor cells express CD47 to escape anti-tumor innate immunity. However, others have shown that the same CD47 antibodies stimulate antibody-dependent tumor cell killing, and studies employing mice lacking the cytoplasmic tail of SIRPα revealed that loss of inhibitory SIRPα signaling is not sufficient to decrease tumor growth [87, 88]. Therefore, additional activities of CD47 must be perturbed by the CD47 antibodies that decrease tumor growth.

6.3. CD47 regulation of cell death

In addition to being a marker of self, signaling through CD47 modulates an array of pathways that regulate cell survival and homeostasis [110]. Several studies indicate that expression CD47 as a functional signaling receptor could be a liability to cancer and tumor stromal cells. Ligation of CD47 results in apoptotic death of T cells. Binding of TSP1 or antibodies such as B6H12 and BRIC126 to CD47 induce apoptosis in B-chronic lymphocyte leukemia and promyelocytic leukemia cells [111]. CD47 mediated cell death is caspase-independent and characterized by a loss in mitochondrial membrane potential, morphology and function [110]. Activation of apoptosis by CD47 ligation has also been observed in solid tumors; ligation of CD47 by 4N1K induces cell death in breast cancer cell lines through regulation of Gi signaling and decreased protein kinase A signaling [112].

CD47 ligation also regulates dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), a mayor regulator of type III programmed cell death in B lymphocytes and leukemia cells. CD47 activation causes translocation of Drp1 from the cytosol to mitochondria [34]. Once in mitochondria, Drp1 inhibits the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which dissipates the mitochondrial transmembrane potential, increases reactive oxygen species generation, and reduces ATP levels.

In contrast to its pro-apoptotic role in leukemias, binding of the TSP1 peptide 4N1 to CD47 induced an anti-apoptotic activity in thyroid carcinoma cells and protected the cells from doxorubicin, ceramide, and camptothecin treatment by down-regulating caspase-3 [113], suggesting that CD47 could be a pharmacological target to overcome cancer drug resistance [111]. CD47 up-regulates astrocytoma cell proliferation when activated with the agonist peptide 4N1 [111]. Protection from death from ionizing radiation was observed in cells or tissues lacking either TSP1 or CD47 [45]. This radioresistant state could be induced in wild type cells and tissues by blockade of CD47 with antisense morpholinos and blocking antibodies [46]. CD47 suppression leads to the protection of bone marrow and soft tissues rendering these resistant to radiation. On the other hand, blockade of CD47 results in the sensitization of melanoma and squamous cell lung carcinoma tumor to radiation. Since blockade of CD47 selectively protects normal tissue, it is possible that by protecting immune cells blockade of CD47 may enhance anti-tumor immunity. This may be mediated by inducing a protective autophagy response in host immune cells [114]. Alternatively, elimination of the don’t eat me signal by blockade of CD47 could enhance tumor immunosurveillance. Regardless of the ultimate mechanism, blockade of CD47 selectively confers radioresistance to normal but not tumor tissues.

TSP1 signaling through CD47 also modulates several processes that indirectly regulate tumor growth. TSP1 at physiological concentrations inhibits angiogenesis through binding CD47 in endothelial cells [115]. Interaction of the carboxyl terminal domain of TSP1 with CD47 inhibits NO-signaling in vascular cells to regulate angiogenesis, blood flow, and platelet hemostasis. Inhibition of VEGF-stimulated tumor angiogenesis by disrupting VEGFR2 association with CD47 is another mechanism by which CD47 antagonists could inhibit tumor growth [116]. Furthermore, TSP1/CD47 signaling can control tumor perfusion through vasopressor activities that indirectly regulate tumor blood flow. Tumor vasculature is relatively unresponsive to vasoactive agents, so peripheral vasodilation caused by inhibiting TSP1/CD47 signaling could reduce tumor blood flow and, consequently, limit tumor growth [115, 117].

In a multiple myeloma model, TSP1/CD47 interactions caused expansion of myeloma cells through modulation of the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK)–RANK ligand (RANK-L) to increase malignancy and metastasis [118]. More recently, elevated expression of CD47 was associated with lymph node metastasis associated with an inverse expression of the micro-RNA miR133a [19]. In cultured cells, miR133a is a direct regulator of CD47 expression. miR133a significantly suppressed tumor growth by regulating cell proliferation, migration and invasion, indicating that the dysregulation or reduction of this micro RNA causes the increased expression of CD47 [19].

6.4. Concluding remarks

Prognostic studies clearly indicate that elevated CD47 expression enhances the progression of some cancers and shortens patient survival. The mechanisms through which elevated expression of CD47 regulates cancer growth and protects from host anti-tumor immunity are complex and involve direct effects on tumor cells as well as indirect effects on vascular and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Targeting tumor CD47 using antibodies or antisense strategies is clearly beneficial in several mouse tumor models, whereas the role of TSP1/CD47 interactions in inhibiting angiogenesis suggests that the same blocking antibodies might increase growth of some tumors by enhancing angiogenesis [115]. Despite our incomplete understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms, these insights provide compelling evidence that targeting CD47 could prove beneficial for the treatment of several types of cancer.

7. Strategies for targeting CD47

Based on their activities in vitro and in animal models, CD47 antibodies are actively being developed as therapeutics (Fig. 3). These include humanized murine anti-human CD47 antibodies, (Fab)2 fragments, and a disulfide-stabilized dimer of a single-chain CD47 antibody fragment [88, 119]. CD47 blocking antibodies have proven effective in a variety of preclinical models including fixed ischemia [42, 65, 120], liver, soft tissue, and renal ischemia/reperfusion [22, 63, 67], pulmonary arterial hypertension [21], skin grafting [60], and several cancer models [17, 18, 88, 121, 122].

Fig. 3. Therapeutic strategies to target CD47.

Therapeutic effects have been reported using TSP1 antibodies that selectively inhibit TSP1/CD47 signaling and using soluble recombinant extracellular domains of CD47 and SIRPα, which act as decoys to selectively block inhibitory signaling through SIRPα. CD47 blocking antibodies such as B6H12 inhibit both TSP1 and SIRPα binding. Antisense suppression of CD47 expression using morpholinos similarly provides global inhibition of CD47 functions. More selective inhibition TSP1/CD47 versus CD47/SIRPα signaling may be achievable using small molecules or peptides designed to inhibit each CD47 interaction.

Two families of synthetic peptides derived from the C-terminal domain of TSP1 bind to CD47 and perturb its interactions and signaling [2]. These have clearly defined activities in vitro and inhibited corneal angiogenesis when locally administered in mice [58], but peptides typically have short circulating half lives in vivo and are subject of enzymatic degradation. Thus, these peptides are unlikely to be effective as systemic therapeutics, but they could serve as pharmacophores for designing potent and stable peptidomimetics such as has been achieved using TSP1 peptides that recognize its receptor CD36 [123, 124].

Antisense strategies are another promising approach to therapeutically inhibit CD47 function. An antisense morpholino oligonucleotide that prevents translation of CD47 mRNA has been used locally and systemically to suppress CD47 expression in mice and miniature pigs and improve tissue survival of ischemic injuries [60, 65, 120]. CD47 morpholino treatment alone minimally inhibited growth of syngenic melanoma or squamous cell carcinomas in mice but synergized with irradiation to delay regrowth of the tumors [46]. In addition to morpholinos, suppression of CD47 expression could potentially be accomplished using siRNA- or miRNA-based therapeutics.

Recombinant extracellular domain of CD47 has also been examined as a decoy to inhibit CD47-SIRPα interactions [84, 125]. CD47-Fc has also been used to modify biocompatible surfaces for preventing platelet and neutrophil activation [126].

8. Preclinical therapeutic applications

8.1. Cardiovascular disease

Results from injury models in mice, rats and pigs indicate that CD47 could be an important therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Beneficial effects were obtained through therapeutic targeting of CD47 or TSP1 using function blocking antibodies and/or antisense suppression of CD47 using morpholino oligonucleotides to increase ischemic wound healing [37, 65, 120], accelerate and improve skin graft take [60], increase blood flow after ischemia in young animals [65, 110], in aged mice and in the presence of diet-associated vasculopathy [42], improve skin blood flow [43], and mitigate of PAH-driven cardiac hypertrophy [21].

8.2. Inflammation and reperfusion injury

Therapeutic blockade of CD47 using antibodies protected mouse liver and kidneys from IRI [22, 63]. Similar protection was obtained in rat soft tissue IRI using the anti-rat CD47 antibody OX101 [67]. Blocking CD47 decreased macrophage and neutrophil recruitment into reperfused tissues and decreased ROS damage in these models. Consistent with an anti-inflammatory effect of CD47 blockade, administration of CD47-Fc suppressed the lymph node accumulation of SIRPα+ dendritic cells, development of systemic and local Th2 responses, and airway inflammation in sensitized and challenged mice [127]. Similarly, administration of soluble SIRP-Fc as a decoy inhibited Langerhans cell migration to lymph nodes and the subsequent contact hypersensitivity upon re-challenge of the mice [128]. Local intradermal administration of a SIRPα blocking antibody or CD47-Fc prevented Langerhans migration induced by dinitrofluorobenzene challenge [129]. Although CD47-null mice were refractory to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), administering a CD47 antibody at the peak of paralysis worsened EAE severity and enhanced immune activation [130], suggesting that CD47-targeted therapeutics may exhibit context-dependent pro- and anti-inflammatory activities.

8.3. Cancer

A bivalent scFv CD47 antibody prolonged survival of mice injected with human multiple myeloma cells [131]. Because neither antibody-dependent nor cell-dependent cytotoxicity was observed, direct effects on CD47 signaling to induce apoptotic myeloma cell death were proposed. In contrast, a number of recent studies have concluded that CD47 blocking antibodies indirectly decrease tumor growth by increasing macrophage-mediated phagocytic killing of various cancers including multiple myeloma [17, 18, 122, 132–134]. However, this conclusion has been challenged by evidence that the same CD47 antibody used in these studies mediates ADCC and by the observation that neutrophils in mice lacking the cytoplasmic signaling domain of SIRPα show no enhanced ability to control tumor growth [87, 88]. Therefore, interactions between CD47 on tumor cells with SIRPα on host macrophages are insufficient to explain the anti-tumor activities of CD47 antibodies [135, 136]. The importance of this SIRPα/CD47 interaction is further questioned by the observation that only a CD47 antibody that does not inhibit CD47/SIRPα binding decreased growth of a syngeneic tumor in mice [18, 135, 136].

Decreasing CD47 expression using a morpholino yielded only a minimal decrease in tumor growth in syngeneic models [46]. However, tumor growth was greatly delayed when the morpholino treatment was combined with irradiation. A similar enhanced tumor growth delay was observed when syngenic tumors grown in TSP1 null mice were irradiated [45], suggesting that blocking CD47/TSP1 interactions is more important than CD47/SIRPα interactions for controlling tumor growth.

9. Conclusion

CD47 and its binding partners play important roles in both acute injury responses and chronic diseases of aging, and blocking these interactions offers great therapeutic promise. The advantages of CD47 and TSP1 null mice in recovering from fixed ischemia, ischemia/reperfusion, and radiation injuries clearly identify CD47 as an important molecular target. Because elevated TSP1 levels are associated with major diseases of aging including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, drugs that block TSP1/CD47 signaling could benefit a large fraction of the aging population. Cancer is the other major disease of aging, and CD47-targeted drugs hold promise to improve patient survival by enhancing innate anti-tumor immunity and by enhancing the efficacy of radiation therapy, which is a component of the standard treatment for a majority of cancers.

10. Expert opinion

Although animal model studies clearly demonstrate that targeting CD47 can provide therapeutic benefits for several diseases, much remains to be done to develop practical therapeutics that target CD47. Presently, rodent monoclonal CD47 antibodies are the most advanced in preclinical development, and several companies are developing humanized or recombinant single chain versions of such antibodies.

Given recent insights into the physiological functions of CD47, potential side effects of therapeutic CD47-antibodies such as B6H12, which inhibits both CD47-SIRP and CD47-TSP1 interactions, include altered blood pressure [36], hemolytic anemia, and prothrombotic or antithrombotic activities [41, 137]. Notably, B6H12 was reported to inhibit platelet activation [138], implying that a humanized therapeutic B6H12 would have anti-thrombotic activity. The latter would be an issue for treating thrombocytopenic cancer patients. Intravenous administration of a CD47 blocking antibody acutely increased blood pressure in mice, presumably by decreasing NO production due to binding to CD47 on endothelial cells [36]. Apart from these pharmacologic side effects, the widespread expression of CD47 on blood cells may provide a barrier to the biodistribution of intravenously administered CD47 antibodies. RBC express ~50,000 copies of CD47/cell [139], which would provide an enormous buffer to limit the availability of intravenously administered CD47 antibodies. This should be less of a problem for applications where the antibodies would be locally administered such as treating ischemic injuries, reconstructive surgery, and perfusion of organs for transplantation.

Antisense or siRNA strategies could offer advantages over CD47 antibodies by avoiding many of the expected cardiovascular side effects. Used short term, such therapeutics should decrease CD47 levels only on cells capable of de novo protein synthesis. Thus, they would not perturb RBC or platelet CD47 levels and should have no acute effects on blood pressure or platelet homeostasis. At a practical level, the ability of a morpholino complementary to human CD47 mRNA to suppress CD47 in mice facilitates preclinical testing of this potential human therapeutic in rodents. Notably, the efficacy in humans of a systemically delivered morpholino targeting mutated dystrophin was recently demonstrated in a phase 2 clinical trial [140].

Small molecules offer advantages in terms of tissue distribution oral availability. Small molecule inhibitors of CD47 could also potentially be designed to selectively inhibit CD47/TSP1 versus CD47/SIRP interactions. This strategy may obviate many of the undesired side effects of broadly inhibiting important physiological functions of CD47.

Article Highlight Box.

CD47 is a cell surface signaling receptor for thrombospondin-1 and the counter-receptor for signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) on phagocytic cells.

Thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling is a physiological regulator of nitric oxide signaling in vascular cells, which regulates angiogenesis, blood pressure, tissue perfusion, and platelet hemostasis.

Elevated thrombospondin-1 levels associated with reperfusion injuries and chronic diseases of aging inhibit nitric oxide signaling.

Antibody and antisense strategies to block CD47 improve tissue survival in rodent models of fixed ischemia, ischemia/reperfusion, and chronic ischemia associated with aging and diet. Benefits of CD47 blockade for treating ischemic injuries extend to higher mammals.

Therapeutic applications supported by preclinical models include reconstructive surgery, skin grafting, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and organ transplantation.

Thrombospondin-1 signaling through CD47 also limits tissue survival of ionizing radiation. Blocking CD47 radioprotects normal tissues by activating a protective autophagy response, whereas treated tumors show enhanced radiosensitivity.

Elevated CD47 expression on several cancers is a negative prognostic indicator. CD47 suppresses innate anti-tumor immunity involving macrophages and NK cells. CD47 antibodies that block SIRPα binding can decrease tumor growth by promoting phagocytic and antibody-dependent tumor cell killing.

CD47 blockade could improve cancer care by enhancing anti-tumor innate immunity and improving tumor responses to radiotherapy while minimizing damage to surrounding tissues.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest:

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NCI (D.D.R.), by a NCI Director’s Career Development Innovation Award (D.R.S-P), by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL108954 2, R01HL089658, 1P01HL103455 to J.S.I.), the American Heart Association (11BGIA7210001 to J.S.I.), the Institute for Transfusion Medicine and the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania (to J.S.I.), and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1016276 C.J. Martin Award to N.M.R.).

References

- 1.Miller YE, Daniels GL, Jones C, et al. Identification of a cell-surface antigen produced by a gene on human chromosome 3 (cen-q22) and not expressed by Rhnull cells. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;41:1061–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frazier WA, Isenberg JS, Kaur S, et al. CD47. UCSD Nature Molecule. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mp.a002870.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg FP, Lublin DM, Telen MJ, et al. Rh-related antigen CD47 is the signal-transducer integrin-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1567–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4*.Poels LG, Peters D, van Megen Y, et al. Monoclonal antibody against human ovarian tumor-associated antigens. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76:781–91. First identification of CD47 over-expression in cancer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai RK, Rodriguez PL, Discher DE. Self inhibition of phagocytosis: the affinity of ‘marker of self’ CD47 for SIRPalpha dictates potency of inhibition but only at low expression levels. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010;45:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6**.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, et al. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051–4. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. Identification of CD47 as a marker of self. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger P, Hilarius-Stokman P, de Korte D, et al. CD47 functions as a molecular switch for erythrocyte phagocytosis. Blood. 2012;119:5512–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao MP, Jaiswal S, Weissman-Tsukamoto R, et al. Calreticulin is the dominant pro-phagocytic signal on multiple human cancers and is counterbalanced by CD47. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:63ra94. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts DD, Miller TW, Rogers NM, et al. The matricellular protein thrombospondin-1globally regulates cardiovascular function and responses to stress. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10*.Kaur S, Kuznetsova SA, Pendrak ML, et al. Heparan sulfate modification of the transmembrane receptor CD47 is necessary for inhibition of T cell receptor signaling by thrombospondin-1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14991–15002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179663. Demonstrated that a specific post-translational modification of CD47 is required to mediate inhibitory signaling by thrombospondin-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maile LA, Capps BE, Miller EC, et al. Glucose regulation of integrin-associated protein cleavage controls the response of vascular smooth muscle cells to insulin-like growth factor-I. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1226–37. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen LB, Capps BE, Miller EC, et al. Glucose-oxidized low-density lipoproteinsenhance insulin-like growth factor I-stimulated smooth muscle cell proliferation by inhibiting integrin-associated protein cleavage. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1321–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhold MI, Lindberg FP, Plas D, et al. In vivo expression of alternatively splicedforms of integrin-associated protein (CD47) J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3419–25. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.11.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Niekerk CC, Ramaekers FC, Hanselaar AG, et al. Changes in expression of differentiation markers between normal ovarian cells and derived tumors. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:157–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Buist MR, Kenemans P, Molthoff CF, et al. Tumor uptake of intravenously administered radiolabeled antibodies in ovarian carcinoma patients in relation to antigen expression and other tumor characteristics. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:92–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640204. First use of CD47 antibodies in humans. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiyama Y, Tanaka T, Naitoh H, et al. Overexpression of integrin-associated protein (CD47) in rat kidney treated with a renal carcinogen, ferric nitrilotriacetate. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:120–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. CD47 blockade enhances phagocytic clearance of leukemia in a mouse model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Willingham SB, Volkmer JP, Gentles AJ, et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. CD47 over-expression was identified as a negative prognostic indicator in several types of solid tumors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki S, Yokobori T, Tanaka N, et al. CD47 expression regulated by the miR-133a tumor suppressor is a novel prognostic marker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:465–72. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.046. Demonstrated CD47 over-expression in stem cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer PM, Bauer EM, Rogers NM, et al. Activated CD47 promotes pulmonary arterial hypertension through targeting caveolin-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:682–93. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Rogers NM, Thomson AW, Isenberg JS. Activation of Parenchymal CD47 Promotes Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020137. in press. Demonstrated therapeutic benefits of CD47 blocking antibody in a kidney transplant model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khandelwal S, van Rooijen N, Saxena RK. Reduced expression of CD47 during murine red blood cell (RBC) senescence and its role in RBC clearance from the circulation. Transfusion. 2007;47:1725–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsson M, Oldenborg PA. CD47 on experimentally senescent murine RBCs inhibits phagocytosis following Fcgamma receptor-mediated but not scavenger receptor-mediated recognition by macrophages. Blood. 2008;112:4259–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odievre MH, Bony V, Benkerrou M, et al. Modulation of erythroid adhesion receptor expression by hydroxyurea in children with sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2008;93:502–10. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang WT, Chen HI, Chiou RJ, et al. A novel function of transcription factor alpha-Pal/NRF-1: increasing neurite outgrowth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Gao AG, Lindberg FP, Dimitry JM, et al. Thrombospondin modulates αvs3 function through integrin-associated protein. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:533–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.533. Identified CD47 as an integrin activator. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.N’Diaye EN, Brown EJ. The ubiquitin-related protein PLIC-1 regulates heterotrimeric G protein function through association with Gbetagamma. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1157–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Frazier WA, Gao A-G, Dimitry J, et al. The thrombospondin receptor integrin-associated protein (CD47) functionally couples to heterotrimeric Gi. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8554–8560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8554. Identified CD47 as a regulator of heterotrimeric G protein signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sick E, Niederhoffer N, Takeda K, et al. Activation of CD47 receptors causes histamine secretion from mast cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1271–82. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manna PP, Frazier WA. The mechanism of CD47-dependent killing of T cells: heterotrimeric Gi-dependent inhibition of protein kinase A. J Immunol. 2003;170:3544–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Lamy L, Ticchioni M, Rouquette-Jazdanian AK, et al. CD47 and the 19 kDa interacting protein-3 (BNIP3) in T cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23915–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301869200. Identified a pathway through which targeting CD47 induces mitochondrial-dependent cell death. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Ney PA. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:939–46. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bras M, Yuste VJ, Roue G, et al. Drp1 mediates caspase-independent type III celldeath in normal and leukemic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7073–88. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02116-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaur S, Martin-Manso G, Pendrak ML, et al. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 signaling by disrupting its association with CD47. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38923–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.172304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer EM, Qin Y, Miller TW, et al. Thrombospondin-1 supports blood pressure by limiting eNOS activation and endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:471–481. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isenberg JS, Shiva S, Gladwin M. Thrombospondin-1-CD47 blockade and exogenous nitrite enhance ischemic tissue survival, blood flow and angiogenesis via coupled NO-cGMP pathway activation. Nitric Oxide. 2009;21:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Isenberg JS, Ridnour LA, Dimitry J, et al. CD47 is necessary for inhibition of nitric oxide-stimulated vascular cell responses by thrombospondin-1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26069–26080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605040200. Identified the key role of CD47 in regulating vascular nitric oxide signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller TW, Isenberg JS, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 is an inhibitor of pharmacological activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:1542–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramanathan S, Mazzalupo S, Boitano S, et al. Thrombospondin-1 and angiotensin II inhibit soluble guanylyl cyclase through an increase in intracellular calcium concentration. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7787–99. doi: 10.1021/bi201060c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isenberg JS, Romeo MJ, Yu C, et al. Thrombospondin-1 stimulates platelet aggregation by blocking the antithrombotic activity of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling. Blood. 2008;111:613–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Pappan LK, et al. Blocking thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling alleviates deleterious effects of aging on tissue responses to ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2582–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155390. Demonstrated therapeutic activity of CD47 blockade in models to overcome age-induced nitric oxide insufficiency. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers NM, Roberts DD, Isenberg JS. Age-associated induction of cell membrane CD47 limits basal and temperature-induced changes in cutaneous blood flow. Ann Surg. 2012 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827e52e1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao M, Roberts DD, Isenberg JS. Thrombospondin-1 inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell responses occurs via modulation of both cAMP and cGMP. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isenberg JS, Maxhimer JB, Hyodo F, et al. Thrombospondin-1 and CD47 limit cell and tissue survival of radiation injury. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1100–1112. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46**.Maxhimer JB, Soto-Pantoja DR, Ridnour LA, et al. Radioprotection in normal tissue and delayed tumor growth by blockade of CD47 signaling. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:3ra7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000139. Demonstrated synergism between CD47 blockade and radiation therapy to control tumor growth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Soto-Pantoja DR, Miller TW, Pendrak ML, et al. CD47 deficiency confers cell and tissue radioprotection by activation of autophagy. Autophagy. 2012 doi: 10.4161/auto.21562. in press. Demonstrated that autophagy mediates the radipoprotective activity of CD47 blockade in healthy cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, et al. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–80. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan S. Molecular mechanisms responsible for the atheroprotective effects of laminar shear stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1669–82. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide as a unique signaling molecule in the vascular system: a historical overview. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;53:503–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung J, Wang XQ, Lindberg FP, et al. Thrombospondin-1 acts via IAP/CD47 to synergize with collagen in alpha2beta1-mediated platelet activation. Blood. 1999;94:642–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albanyan AM, Harrison P, Murphy MF. Markers of platelet activation and apoptosis during storage of apheresis-and buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates for 7 days. Transfusion. 2009;49:108–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo YL, Liu DQ, Bian Z, et al. Down-regulation of platelet surface CD47 expression in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection-induced thrombocytopenia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Frazier WA. The thrombospondin receptor CD47 (IAP) modulates and associates with α2β1 integrin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:865–874. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freyberg MA, Kaiser D, Graf R, et al. Proatherogenic flow conditions initiate endothelial apoptosis via thrombospondin-1 and the integrin-associated protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:141–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sajid M, Hu Z, Guo H, et al. Vascular expression of integrin-associated protein and thrombospondin increase after mechanical injury. J Investig Med. 2001;49:398–406. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.33784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Isenberg JS, Annis DS, Pendrak ML, et al. Differential interactions of thrombospondin-1, -2, and -4 with CD47 and effects oncGMP signaling and ischemic injury responses. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1116–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804860200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Kanda S, Shono T, Tomasini-Johansson B, et al. Role of thrombospondin-1-derived peptide, 4N1K, in FGF-2-induced angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:262–72. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4622. First demonstration of a role for CD47 to limit angiogenesis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isenberg JS, Ridnour LA, Perruccio EM, et al. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits endothelial cell responses to nitric oxide in a cGMP-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13141–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502977102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isenberg JS, Pappan LK, Romeo MJ, et al. Blockade of thrombospondin-1-CD47 interactions prevents necrosis of full thickness skin grafts. Ann Surg. 2008;247:180–90. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815685dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hausman MR, Rinker BD. Intractable wounds and infections: the role of impaired vascularity and advanced surgical methods for treatment. Am J Surg. 2004;187:44S–55S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xing C, Lee S, Kim WJ, et al. Neurovascular effects of CD47 signaling: promotion of cell death, inflammation, and suppression of angiogenesis in brain endothelialcells in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2571–7. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63*.Isenberg JS, Maxhimer JB, Powers P, et al. Treatment of ischemia/reperfusion injury by limiting thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling. Surgery. 2008;144:752–61. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.009. Demonstrated benefit of CD47 blockade in treating reperfusion injury in a mouse model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, et al. Thrombospondin-1 limits ischemic tissue survival by inhibiting nitric oxide-mediated vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Blood. 2007;109:1945–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65**.Isenberg JS, Romeo MJ, Abu-Asab M, et al. Increasing survival of ischemic tissue by targeting CD47. Circ Res. 2007;100:712–20. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259579.35787.4e. First therapeutic model to demonstrate benefits of CD47 blockade to treat ischemic injuries. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maile LA, Allen LB, Hanzaker CF, et al. Glucose regulation of thrombospondin and its role in the modulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation. Exp Diabetes Res. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/617052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maxhimer JB, Shih HB, Isenberg JS, et al. Thrombospondin-1-CD47 blockade following ischemia reperfusion injury is tissue protective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1880–1889. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bceec3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hart ECm, Charkoudian N. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in human blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:237–43. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh M, Mensah GA, Bakris G. Pathogenesis and clinical physiology of hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:545–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Forstermann U, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:829–37. 837a–837d. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Curwen JO, Musgrove HL, Kendrew J, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-a signaling induces hypertension: examining the effect of cediranib (recentin; AZD2171) treatment on blood pressure in rat and the use of concomitant antihypertensive therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3124–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72*.Isenberg JS, Qin Y, Maxhimer JB, et al. Thrombospondin-1 and CD47 regulate blood pressure and cardiac responses to vasoactive stress. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:110–9. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.01.002. Physiological function of CD47 in blood pressure regulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ochoa CD, Yu L, Al-Ansari E, et al. Thrombospondin-1 null mice are resistant to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:32. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-5-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chaulet H, Lin F, Guo J, et al. Sustained augmentation of cardiac alpha1A-adrenergic drive results in pathological remodeling with contractile dysfunction, progressive fibrosis and reactivation of matricellular protein genes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:540–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75*.Lindberg FP, Bullard DC, Caver TE, et al. Decreased resistance to bacterial infection and granulocyte defects in IAP-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:795–8. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.795. Identified a necessary function of CD47 in innate immunity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herold S, von Wulffen W, Steinmueller M, et al. Alveolar epithelial cells direct monocyte transepithelial migration upon influenza virus infection: impact of chemokines and adhesion molecules. J Immunol. 2006;177:1817–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Azcutia V, Stefanidakis M, Tsuboi N, et al. Endothelial CD47 Promotes Vascular Endothelial-Cadherin Tyrosine Phosphorylation and Participates in T Cell Recruitment at Sites of Inflammation In Vivo. J Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chin AC, Fournier B, Peatman EJ, et al. CD47 and TLR-2 cross-talk regulates neutrophil transmigration. J Immunol. 2009;183:5957–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van VQ, Lesage S, Bouguermouh S, et al. Expression of the self-marker CD47 on dendritic cells governs their trafficking to secondary lymphoid organs. EMBO J. 2006;25:5560–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li Z, Calzada MJ, Sipes JM, et al. Interactions of thrombospondins with α4β1 integrin and CD47 differentially modulate T cell behavior. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:509–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matozaki T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, et al. Functions and molecular mechanisms of the CD47-SIRPalpha signalling pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blazar BR, Lindberg FP, Ingulli E, et al. CD47 (integrin-associated protein) engagement of dendritic cell and macrophage counterreceptors is required to prevent the clearance of donor lymphohematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:541–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83*.Wang C, Wang H, Ide K, et al. Human CD47 expression permits survival of porcine cells in immunodeficient mice that express SIRPalpha capable of binding to human CD47. Cell Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.3727/096368911X566253. Describes a strategy using CD47 expression to overcome a barrier to xenotransplantion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ide K, Wang H, Tahara H, et al. Role for CD47-SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5062–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609661104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang H, Madariaga ML, Wang S, et al. Lack of CD47 on nonhematopoietic cells induces split macrophage tolerance to CD47null cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13744–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702881104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86**.Kim MJ, Lee JC, Lee JJ, et al. Association of CD47 with natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity of head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Tumour Biol. 2008;29:28–34. doi: 10.1159/000132568. First demonstration that CD47blockade can enhance anti-tumor innate immunity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao XW, Kuijpers TW, van den Berg TK. Is targeting of CD47-SIRPalpha enough for treating hematopoietic malignancy? Blood. 2012;119:4333–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391367. author reply 4334–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88**.Zhao XW, van Beek EM, Schornagel K, et al. CD47-signal regulatory protein-alpha (SIRPalpha) interactions form a barrier for antibody-mediated tumor cell destruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106550108. CD47 blockade enhances antibody-dependent tumor killing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ticchioni M, Deckert M, Mary F, et al. Integrin-associated protein (CD47) is a comitogenic molecule on CD3-activated human T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:677–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilson KE, Li Z, Kara M, et al. β1 integrin-and proteoglycan-mediated stimulation of T lymphoma celladhesion and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling by thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-1 peptides. J Immunol. 1999;163:3621–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Z, He L, Wilson KE, et al. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits TCR-mediated T lymphocyte early activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:2427–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92*.Reinhold MI, Lindberg FP, Kersh GJ, et al. Costimulation of T cell activation by integrin-associated protein (CD47) is an adhesion-dependent, CD28-independent signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.1. Indentified a mechanism through which CD47 ligation enhances T cell activation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reinhold MI, Green JM, Lindberg FP, et al. Cell spreading distinguishes the mechanism of augmentation of T cell activation by integrin-associated protein/CD47 and CD28. Int Immunol. 1999;11:707–18. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Piccio L, Vermi W, Boles KS, et al. Adhesion of human T cells to antigen-presenting cells through SIRPbeta2-CD47 interaction costimulates T-cell proliferation. Blood. 2005;105:2421–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitmentand plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Latour S, Tanaka H, Demeure C, et al. Bidirectional negative regulation of human T and dendritic cells by CD47 and its cognate receptor signal-regulator protein-alpha: down-regulation of IL-12 responsiveness and inhibition of dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:2547–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Avice MN, Rubio M, Sergerie M, et al. CD47 ligation selectively inhibits the development of human naive T cells into Th1 effectors. J Immunol. 2000;165:4624–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bouguermouh S, Van VQ, Martel J, et al. CD47 expression on T cell is a self-control negative regulator of type 1 immune response. J Immunol. 2008;180:8073–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lamy L, Foussat A, Brown EJ, et al. Interactions between CD47 and thrombospondin reduce inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178:5930–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vallbo C, Damber JE. Thrombospondins, metallo proteases and thrombospondin receptors messenger RNA and protein expression in different tumour sublines of the Dunning prostate cancer model. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:293–8. doi: 10.1080/02841860410002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rendtlew Danielsen JM, Knudsen LM, Dahl IM, et al. Dysregulation of CD47 and the ligands thrombospondin 1 and 2 in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:756–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Raetz EA, Perkins SL, Bhojwani D, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals intrinsic differences between T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:130–40. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Suhr ML, Dysvik B, Bruland O, et al. Gene expression profile of oral squamous cell carcinomas from Sri Lankan betel quid users. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:1061–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chan KS, Espinosa I, Chao M, et al. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14016–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906549106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nagahara M, Mimori K, Kataoka A, et al. Correlated expression of CD47 and SIRPA in bone marrow and in peripheral blood predicts recurrence in breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4625–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sarfati M, Fortin G, Raymond M, et al. CD47 in the immune response: role of thrombospondin and SIRP-alpha reverse signaling. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:842–50. doi: 10.2174/138945008785909310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Uluckan O, Becker SN, Deng H, et al. CD47 regulates bone mass and tumor metastasis to bone. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3196–204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Martin-Manso G, Galli S, Ridnour LA, et al. Thrombospondin-1 promotes tumor macrophage recruitment and enhances tumor cell cytotoxicity by differentiated U937 cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7090–7099. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jaiswal S, Chao MP, Majeti R, et al. Macrophages as mediators of tumor immunosurveillance. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Soto-Pantoja DR, Isenberg JS, Roberts DD. Therapeutic Targeting of CD47 to Modulate Tissue Responses to Ischemia and Radiation. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2011:2. doi: 10.4172/2157-7412.1000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sick E, Jeanne A, Schneider C, et al. CD47 update: a multi-faceted actor in the tumour microenvironment of potential therapeutic interest. Br J Pharmacol. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112*.Manna PP, Frazier WA. CD47 mediates killing of breast tumor cells via Gi-dependent inhibition of protein kinase A. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1026–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1708. A strategy to directly kill tumor cells by targeting CD47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rath GM, Schneider C, Dedieu S, et al. Thrombospondin-1 C-terminal-derived peptide protects thyroidcells from ceramide-induced apoptosis through the adenylyl cyclase pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:2219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Soto-Pantoja DR, Miller TW, Pendrak ML, et al. CD47 deficiency confers cell and tissue radioprotection by activation of autophagy. Autophagy. 2012:8. doi: 10.4161/auto.21562. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Isenberg JS, Martin-Manso G, Maxhimer JB, et al. Regulation of nitric oxide signalling by thrombospondin 1: implications for anti-angiogenic therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:182–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kaur S, Roberts DD. CD47 applies the brakes to angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:10–2. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.1.14324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Ridnour LA, et al. Thrombospondin-1 and vasoactive agents indirectly alter tumor blood flow. Neoplasia. 2008;10:886–896. doi: 10.1593/neo.08264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kukreja A, Radfar S, Sun BH, et al. Dominant role of CD47-thrombospondin-1 interactions in myeloma-induced fusion of human dendritic cells: implications for bone disease. Blood. 2009;114:3413–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sagawa M, Shimizu T, Fukushima N, et al. A new disulfide-linked dimer of a single-chain antibody fragment against human CD47 induces apoptosis in lymphoid malignant cells via the hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha pathway. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1208–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Isenberg JS, Romeo MJ, Maxhimer JB, et al. Gene silencing of CD47 and antibody ligation of thrombospondin-1 enhance ischemic tissue survival in a porcine model: implications for human disease. Ann Surg. 2008;247:860–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816c4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.van Ravenswaay Claasen HH, Eggermont AM, Nooyen YA, et al. Immunotherapy in a human ovarian cancer xenograft model with two bispecific monoclonal antibodies: OV-TL 3/CD3 and OC/TR. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:199–206. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of CD47 eliminates human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1374–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Haviv F, Bradley MF, Kalvin DM, et al. Thrombospondin-1 mimetic peptide inhibitors of angiogenesis and tumor growth: design, synthesis, and optimization of pharmacokinetics and biological activities. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2838–46. doi: 10.1021/jm0401560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Henkin J, Volpert OV. Therapies using anti-angiogenic peptide mimetics of thrombospondin-1. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:1369–86. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.640319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fortin G, Raymond M, Van VQ, et al. A role for CD47 in the development of experimental colitis mediated by SIRPalpha+CD103-dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1995–2011. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Finley MJ, Rauova L, Alferiev IS, et al. Diminished adhesion and activation of platelets and neutrophils with CD47 functionalized blood contacting surfaces. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5803–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]