Abstract

Objectives. We compared five parathyroid scintigraphy protocols in patients with primary (pHPT) and secondary hyperparathyroidism (sHPT) and studied the interobserver agreement. The dual-tracer method (99mTc-sestamibi/123I) was used with three acquisition techniques (parallel-hole planar, pinhole planar, and SPECT/CT). The single-tracer method (99mTc-sestamibi) was used with two acquisition techniques (double-phase parallel-hole planar, and SPECT/CT). Thus five protocols were used, resulting in five sets of images. Materials and Methods. Image sets of 51 patients were retrospectively graded by four experienced nuclear medicine physicians. The final study group consisted of 24 patients (21 pHPT, 3 sHPT) who had been operated upon. Surgical and histopathologic findings were used as the standard of comparison. Results. Thirty abnormal parathyroid glands were found in 24 patients. The sensitivities of the dual-tracer method (76.7–80.0%) were similar (P = 1.0). The sensitivities of the single-tracer method (13.3–31.6%) were similar (P = 0.625). All differences in sensitivity between these two methods were statistically significant (P < 0.012). The interobserver agreement was good. Conclusion. This study indicates that any dual-tracer protocol with 99mTc-sestamibi and 123I is superior for enlarged parathyroid gland localization when compared with single-tracer protocols using 99mTc-sestamibi alone. The parathyroid scintigraphy was found to be independent of the reporter.

1. Introduction

99mTc-methoxyisobutylisonitrile (99mTc-sestamibi), first introduced by Coakley and coworkers as a parathyroid imaging agent in 1989 [1], is the imaging agent of choice for parathyroid scintigraphy (PS) [2]. Unfortunately, 99mTc-sestamibi is not a specific tracer for parathyroid tissue but is taken up by adjacent thyroid tissue. This problem can be overcome by using either a single-tracer (double phase) or a dual-tracer method.

In the single tracer method, it is assumed that thyroid and parathyroid tissues have different washout kinetics for 99mTc-sestamibi [3]. By acquiring images in the early and late phases, the focally increasing uptake will reveal hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue. In the dual-tracer method, 99mTc-sestamibi is used combined with 123I or 99mTc-pertechnetate, which are taken up by the thyroid gland only. Subtracting the thyroid image from the 99mTc-sestamibi image provides visualization of the parathyroid tissue alone [4].

With both single-tracer and dual-tracer methods, several acquisition techniques can be used (i.e., planar acquisitions with parallel-hole or pinhole collimators and SPECT or SPECT/CT), and several choices can be made about the settings used for each technique (e.g., matrix size, energy settings, and acquisition time). There are several studies that provide comparisons between the different imaging methods or techniques, although there is little evidence supporting the superiority of one over another, resulting in the use of various study protocols today [5, 6].

We have previously shown that there is significant variability in the current practice of PS in Finland [7]. This is also true in other countries, with reported sensitivities for localizing abnormal parathyroid tissue ranging from 34% to 100% [8].

As a result of our previous study, the clinical protocol of parathyroid scintigraphy in Satakunta central hospital was changed in June 2010. Pinhole and SPECT/CT acquisition techniques were included to increase the sensitivity of the study. Additional late phase imaging was also included to benefit from the double phase method as well.

The goal of this study was to compare the sensitivity and specificity of a single-tracer method and a dual-tracer method with various acquisition techniques. The dual-tracer method (99mTc-sestamibi/123I) was used with three acquisition techniques (parallel-hole planar, pinhole planar, and SPECT/CT). The single-tracer method (99mTc-sestamibi) was used with two acquisition techniques (double phase parallel-hole planar, and SPECT/CT). In addition, the agreement between the findings of four experienced nuclear medicine physicians was studied.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

This was a retrospective single-center study of fifty-one patients referred for PS between June 2010 and February 2011 in Satakunta Central Hospital, Finland. Patient data were included if there was biochemical evidence of hyperparathyroidism, if scintigraphy was requested for preoperative tumor localization, and if the patient proceeded to surgery. Histopathological finding was used as the gold standard. The final study group consisted of 6 men and 18 women with a mean age of 62.3 years (range, 32.1–86.8 years). Twenty-one patients had pHPT. Preoperative plasma intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) values ranged from 69 ng/L to 277 ng/L (mean 190 ng/L, normal values 10–65 ng/L), and values for preoperative serum calcium (Ca) ranged from 1.37 mmol/L to 1.73 mmol/L (mean 1.48 mmol/L, normal values 1.16–1.3 mmol/L). Three patients had sHPT due to renal failure. Preoperative iPTH values ranged from 210 ng/L to 400 ng/L (mean 380 ng/L), values for preoperative Ca ranged from 1.21 mmol/L to 1.8 mmol/L (mean 1.45 mmol/L). Twenty-seven patients did not proceed to surgery for a variety of reasons (patient condition, death, and other illnesses). This study was exempt from institutional review board approval according to Finnish legislation. Informed consent was waived.

2.2. Imaging: Doses and Acquisition

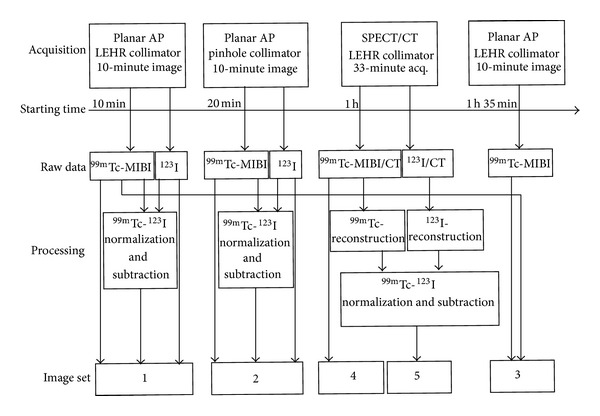

Patients received 20 MBq of 123I (MAP Medical Technologies) intravenously. Two hours later, 550 MBq of 99mTc-sestamibi (Mallinckrodt Medical B.V.) was injected intravenously. Ten minutes after the 99mTc-sestamibi administration, imaging was started. Five different image sets were acquired. The order and the timing (after the injection or 99mTc-sestamibi) of the acquisitions and the resulting image sets are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The orders and the timings of the acquisitions and the resulting image sets. Set 1: 99mTc-sestamibi, 123I, and subtraction images with parallel-hole collimator. Set 2: 99mTc-sestamibi, 123I, and subtraction images with pinhole collimator. Set 3: 99mTc-sestamibi double phase images with parallel-hole collimator. Set 4: 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT. Set 5: 99mTc-sestamibi, 123I, and subtraction SPECT/CT images.

First, a static 10-minute anterior image of the neck and chest was acquired using a low-energy, high-resolution, parallel-hole collimator (LEHR) (256 × 256 matrix; 1.85x zoom). Next, a static 10-minute anterior image of the neck was acquired from a distance of 10 cm from the patient's skin using a 5 mm diameter pinhole collimator (256 × 256 matrix; 2.19x zoom). Acquisitions were performed with the same dual-head gamma camera (Skylight; Philips). All data were collected in dual-energy windows. The 99mTc window was centered at 140 keV and had a 10% width (range, 133–147 keV). The 123I window was centered at 159 keV and had a 10% width (range, 151–167 keV). Narrow windows were used to minimize crosstalk between isotopes.

One hour after the 99mTc-sestamibi injection, the SPECT/CT acquisition was started (Symbia T; Siemens). SPECT data were acquired in a step-and-shoot sequence with a noncircular orbit (180° detector configuration; low-energy, parallel-hole, high-resolution collimators; 128 × 128 matrix; 4.8 mm pixel size; 48 views for each detector (3,75° per projection); 33 s/projection; total scan time, 32 min). All data were collected in dual-energy windows. The 99mTc window was centered at 140 keV and had a 15% width (range, 129.5–150.5 keV). The 123I window was placed with a 4% offset above 159 keV and had a 15% width (range, 153.4–177.3 keV). The 4% offset was used to minimize the spillover of the 99mTc photopeak into the 123I photopeak. After the SPECT acquisition was complete, the patient remained still on the table for the CT acquisition. A topogram scout scan (130 kVp, 30 mA, anterior view) was performed first, and limits for the CT acquisition were set (from the neck to the diaphragm). Then, a helical CT scan was performed (130 kVp, 2 × 2.5 mm collimation, 0.8 s rotation time, 1.5 pitch). The dose was controlled by tube-current modulation (CARE Dose AEC+DOM; Siemens), with the reference exposure set to 30 mAs.

Finally, a static 10-minute anterior image of the neck and chest was acquired using a low-energy, high-resolution collimator with a Siemens Symbia T-gamma camera (256 × 256 matrix; 1.85x zoom (32.2 cm field)). The same energy settings as those in the SPECT acquisition were used. Eleven of the patients did not complete this final image due to limited camera time or patient-related reasons. A 99mTc intrinsic flood was used for both energy windows in both cameras. It was verified that the image-field uniformity was acceptable for all energy windows used.

2.3. Image Processing

All planar images were analyzed in a Hermes workstation (Hermes Medical Solutions). For dual-tracer images, a normalization factor (NF) was defined as the ratio of the thyroid maximum pixel counts in the 123I and 99mTc-sestamibi images. Gradient subtraction images were created by multiplying the 99mTc-sestamibi image with 10 successive NFs (with 20% steps from 20% to 200% of the original NF), and the 123I image was subtracted from each normalized 99mTc-sestamibi image, resulting in 10 subtraction images to avoid oversubtraction [9, 10]. The final image sets consisted of 99mTc-sestamibi and 123I images and gradient subtraction images (image set 1 acquired with LEHR, image set 2 with pinhole). 99mTc-sestamibi early- and late-phase images were displayed side-by-side on the Hermes workstation (image set 3).

SPECT images were reconstructed on the Siemens Syngo workstation (Siemens) using the FLASH 3D algorithm (8 iterations, 8 subsets, Gaussian 9.00 filter). No scatter correction was used. The initial NF was defined as the ratio of the corresponding thyroid maximum voxel counts in 99mTc-sestamibi and 123I SPECT data. 123I SPECT data were multiplied by NF to create normalized 123I SPECT data, which were then subtracted from 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT data to create the subtraction SPECT dataset, as described by Neumann and coworkers [4]. The NF was adjusted until the subtraction SPECT images were subjectively satisfactory. CT data were reconstructed on the Siemens Syngo workstation (Siemens) for attenuation correction using the B08s kernel, and for fusion display purposes with a B40s medium kernel. The CT images were downsampled to match the SPECT image matrix and converted from Hounsfield units into effective attenuation values at 140 keV (99mTc) and 159 keV (123I). The final image sets consisted of 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT data (image set 4) and 123I, 99mTc-sestamibi, and subtraction SPECT/CT data (image set 5). The accuracy of the SPECT/CT data coregistration was checked. All image processing was performed by an experienced medical physicist.

2.4. Image Interpretation

All patient image datasets were anonymized before review by four experienced nuclear medicine physicians, who were blinded to all patient-related information. Five image sets (Figure 1) were reviewed. Datasets 1, 2, and 3 were read in separate reading sessions. Image sets 4 and 5 were reviewed in a single session in this order, with the physician being aware that the datasets belonged to the same patient.

Each quadrant in relation to the thyroid gland (right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower) was classified on a 3-point scale (0 = negative, 1 = uncertain, and 2 = positive). The image review criteria for positive finding were as follows: (a) for image sets 1 and 2: clear abnormal residual activity on the planar subtraction images, (b) for image set 3: focally increased uptake that persisted or increased in intensity from early to late images, (c) for image set 4: focally increased uptake outside the normal 99mTc-sestamibi biodistribution that had an anatomic correlation in the CT images, and (d) for image set 5: clear abnormal residual activity on the subtraction SPECT images that had an anatomic correlation in the CT images.

2.5. Surgery and Histologic Analysis

All patients were operated upon by an endocrine surgeon using an open technique. The surgeon was aware of all initial scintigraphic results prior to surgery. All glands were not identified for all patients. Postoperative iPTH and Ca values were reviewed to confirm surgery success. The mean interval between scintigraphy and surgery was 181 days (range, 29–457 days). A histopathological analysis was performed for all excised tissue.

2.6. Data Analysis

To estimate the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for the localization for each image set, scores of 0-1 were considered negative and scores of 2 were considered positive. Findings were classified as true positive, false positive, true negative, or false negative with histologic analysis as the reference standard. For each patient, four scores, one for each quadrant, were assigned. The false-positive image rate was defined as the ratio of false positives to the sum of true positives plus false positives [11].

2.7. Statistical Methods

The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of each image set were calculated for each physician separately. A McNemar test was performed to compare the sensitivities, specificities, and accuracies between the image sets. The results from physician 1 were chosen when comparing the image sets, as he had the most experience with the imaging methods and techniques used. The Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test was used to compare the size of the visualized and nonvisualized glands. A McNemar test was also used to analyze the accuracy of the different physicians. The differences for each method/technique were analyzed separately. κ coefficients were used to quantify the agreement between the results from the four physicians. Positive kappa values within the ranges of 0.01–0.20, 0.21–0.4, 0.41–0.60, 0.61–0.80, and 0.81–1.00 were interpreted as “very weak,” “weak,” “medium,” “good,” and “very good” agreement, respectively [12]. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and SPSS statistical analysis software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Histological Findings

Altogether, 30 enlarged glands were found in 24 patients. Twenty patients had a solitary parathyroid adenoma, two patients had double adenomas, and two patients had multiglandular disease. The mean weight of the abnormal parathyroid glands was 677 mg (weight information was not available for four glands).

The postoperative serum Ca values were normalized for all patients. The postoperative iPTH values were normalized for 17 patients. For 7 patients, these values were slightly elevated (ranged from 80 ng/L to 134 ng/L (mean 90 ng/L), but decreased from the preoperative values (ranged from 138 ng/L to 400 ng/L (mean 165 ng/L)). Four glands were visualized in the operation for these patients.

The pathological findings together with the image findings for physician 1 are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of adenomas and hyperplastic glands and image findings for physician 1.

| Patient number | Gland number | Weight (mg) | Findings for image set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 170 | FN | FN | NA | FN | FN |

| 1 | 2 | 570 | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 2 | 3 | 980 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 3 | 4 | 830 | TP | TP | FN | TP | TP |

| 4 | 5 | 1280 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 4 | 6 | 840 | TP | FN | FN | FN | TP |

| 4 | 7 | 2140 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 5 | 8 | NA | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 6 | 9 | 1200 | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 7 | 10 | 960 | TP | TP | TP | TP | TP |

| 8 | 11 | 1880 | TP | TP | TP | FN | TP |

| 9 | 12 | 1160 | FN | TP | FN | FN | FN |

| 10 | 13 | 299 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 11 | 14 | 200 | FN | FN | FN | FN | FN |

| 12 | 15 | 260 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 13 | 16 | 570 | TP | TP | TP | TP | TP |

| 14 | 17 | 370 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 15 | 18 | 300 | TP | FN | NA | FN | FN |

| 15 | 19 | 400 | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 15 | 20 | NA | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 16 | 21 | 510 | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 17 | 22 | 340 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 18 | 23 | NA | TP | TP | TP | FN | TP |

| 19 | 24 | 420 | FN | FN | TP | FN | FN |

| 20 | 25 | 300 | FN | TP | NA | FN | FN |

| 20 | 26 | NA | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 21 | 27 | 520 | TP | TP | NA | FN | TP |

| 22 | 28 | 400 | TP | TP | FN | FN | TP |

| 23 | 29 | 550 | TP | TP | TP | TP | TP |

| 24 | 30 | 160 | FN | FN | FN | FN | FN |

TP: true positive for abnormal parathyroid gland; FN: false negative for abnormal parathyroid gland; NA: image set not available for patient.

3.2. 99mTc-Sestamibi versus 123I/99mTc-Sestamibi

All image sets with 123I/99mTc-sestamibi were significantly more sensitive than any image set with 99mTc-sestamibi, regardless of the acquisition technique (Tables 2 and 3). 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT (image set 4) had the highest specificity (100%), as there were no false-positive readings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for localization of abnormal parathyroid glands.

| Image set | Physician | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 80.0 | 93.9 | 89.6 |

| 2 | 70.0 | 95.5 | 87.5 | |

| 3 | 63.3 | 97.0 | 86.5 | |

| 4 | 63.3 | 97.0 | 86.5 | |

|

| ||||

| 2 | 1 | 80.0 | 92.4 | 88.5 |

| 2 | 80.0 | 93.9 | 89.6 | |

| 3 | 76.7 | 95.5 | 89.6 | |

| 4 | 76.7 | 95.5 | 89.6 | |

|

| ||||

| 3 | 1 | 31.6 | 93.9 | 76.5 |

| 2 | 21.1 | 98.0 | 76.5 | |

| 3 | 10.5 | 100.0 | 75.0 | |

| 4 | 15.8 | 100.0 | 76.5 | |

|

| ||||

| 4 | 1 | 13.3 | 100.0 | 72.9 |

| 2 | 16.7 | 100.0 | 74.0 | |

| 3 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 71.9 | |

| 4 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 71.9 | |

|

| ||||

| 5 | 1 | 76.7 | 92.4 | 87.5 |

| 2 | 76.7 | 95.5 | 89.6 | |

| 3 | 56.7 | 98.5 | 85.4 | |

| 4 | 63.3 | 98.5 | 87.5 | |

Table 3.

Statistical significance for differences in sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for comparisons of image sets for physician 1.

| Compared image sets | P for sensitivity | P for specificity | P for accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 versus 2 | NS | NS | NS |

| 1 versus 3 | 0.0117 | NS | 0.0352 |

| 1 versus 4 | 1.907E − 06 | 0.0455 | 0.0015 |

| 1 versus 5 | NS | NS | NS |

| 2 versus 3 | 0.0117 | NS | NS |

| 2 versus 4 | 1.907E − 06 | 0.0253 | 0.0041 |

| 2 versus 5 | NS | NS | NS |

| 3 versus 4 | NS | NS | NS |

| 3 versus 5 | 0.0117 | NS | NS |

| 4 versus 5 | 3.815E − 06 | 0.0253 | 0.0066 |

NS: not significant.

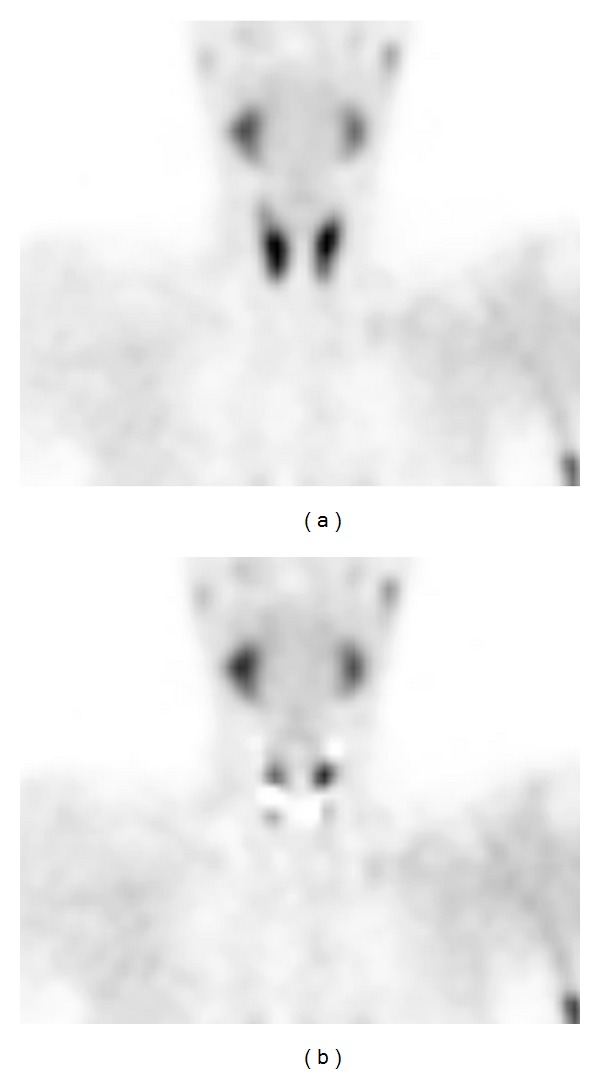

99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT revealed only 4 abnormal glands, while 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT revealed 23 abnormal glands (Table 1). A representative patient case is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

99mTc-sestamibi SPECT (a) and 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT (b) coronal images for a 34-year-old man with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Three hyperplastic parathyroid glands not visualized in coronal 99mTc-sestamibi image are clearly visible in the subtraction SPECT coronal image (b).

3.3. Planar AP with LEHR versus Planar AP with Pinhole versus SPECT/CT

There was no difference in the sensitivity, specificity, or accuracy between the acquisition techniques using 99mTc-sestamibi alone. There was also no difference in the sensitivity, specificity, or accuracy between the acquisition techniques using 123I/99mTc-sestamibi (Tables 2 and 3).

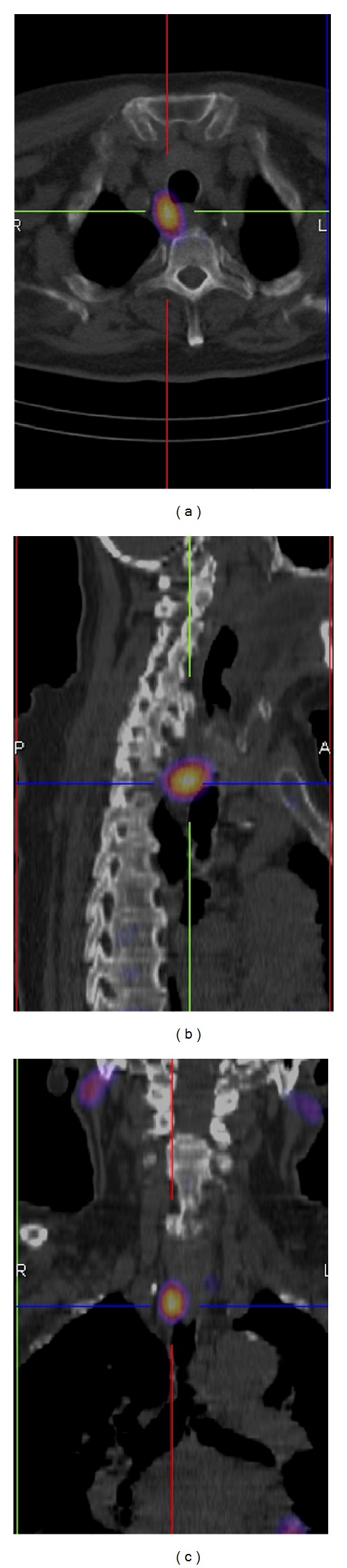

Although there was no difference in the sensitivity, SPECT/CT may offer invaluable three-dimensional information about the location of the enlarged parathyroid adenomas together with anatomical information (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A 99mTc-sestamibi uptake in a parathyroid adenoma located behind the trachea. 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT images (transversal (a), sagittal (b), and coronal (c)).

3.4. False-Positive Findings

Ten patients had 12 different false-positive findings (40 false-positive findings if all physicians and image sets are summed up). The false-positive findings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The false-positive findings for all physicians.

| Image set | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | Reason for FP | % of FP | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient number | Physician | Physician | Physician | Physician | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 2 | RL | RL | Uneven iodine uptake | 55 | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | ||||||||

| 8 | RU | RU | ||||||||||||||||

| 22 | RU | RU | RU | RU | RU | RU | RU | RU | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | RL | Bone uptake | 20 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | LL | Edge effect | 10 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | LL | |||||||||||||||||

| 24 | RU | RU | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | LL | Other | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| 24 | RL | RL | RL | |||||||||||||||

| 13 | LU | |||||||||||||||||

| 19 | LL | |||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| % of FP | 27.5 | 37.5 | 10 | 25 | ||||||||||||||

FP: false positive, RU: right upper, RL: right lower, LU: left upper, and LL: left lower.

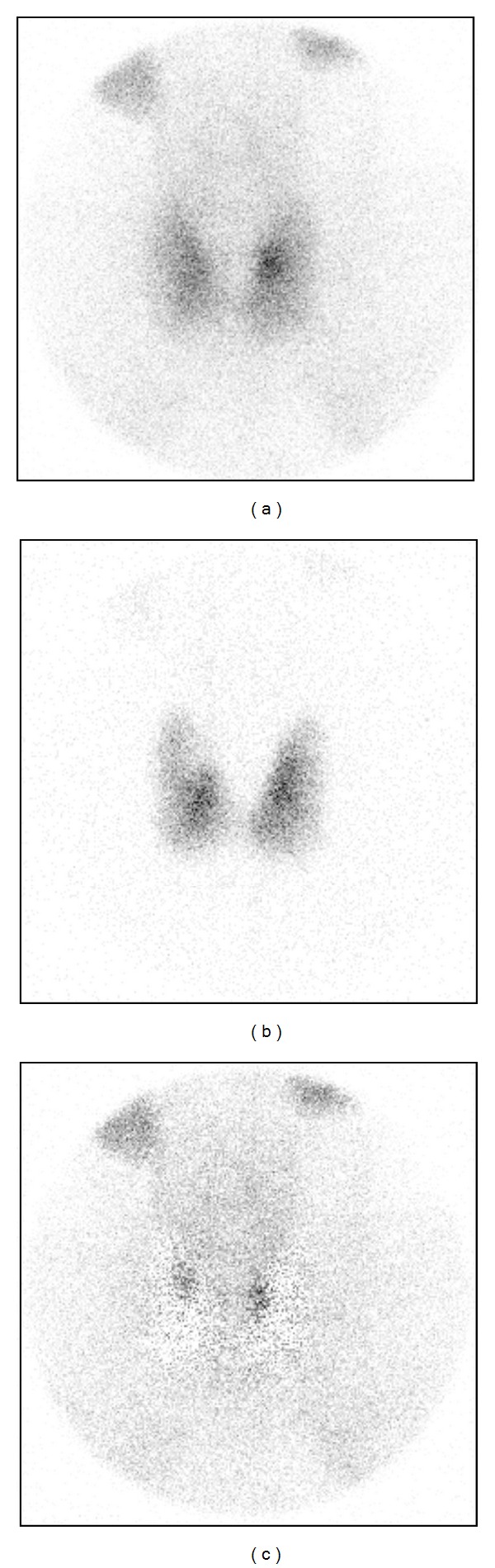

Four of these were due to cold thyroid nodules in 123I images, causing erroneous interpretation in the subtraction image (Figure 4). Uneven 123I uptake caused thus 55% of all false-positive findings.

Figure 4.

A cold nodule in the upper quadrant of a right thyroid lobe in the 123I image (b) causing a false-positive finding in the subtraction image (c).

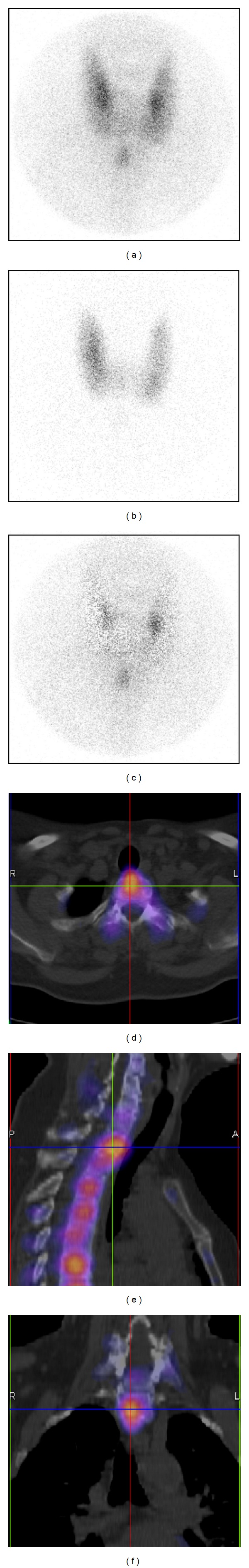

One patient had clear uptake in the 99mTc-sestamibi image below the thyroid as seen in planar images. All physicians interpreted this as a positive finding in the planar images. In the SPECT/CT images, it was revealed that the uptake was in the cervical vertebra (Figure 5). This bone uptake caused 20% of all false-positive findings.

Figure 5.

A 99mTc-sestamibi focal uptake inferior to the thyroid seen in the anterior image acquired with a pinhole collimator. 99mTc-sestamibi (a), 123I (b), and subtraction image (c). All physicians interpreted this uptake as an abnormal parathyroid gland. The same patient seen in 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT images (transversal (d), sagittal (e), and coronal (f)). Focal uptake was due to bone uptake in the cervical vertebra.

Three false positive findings were due to the “edge effect” in 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT images (residual activity around the thyroid lobes after subtraction). This artefact caused 10% of all false-positive findings.

Four positive findings were caused by an error in image interpretation, mainly in double phase 99mTc-sestamibi images. Difficulty in setting the line between the positive and the negative findings caused 15% of all false-positive findings.

As seen in Table 4, 123I/99mTc-sestamibi dual-tracer method with various acquisition techniques produced 90% of all false-positive findings. Subtraction SPECT/CT yielded the lowest percentage of false positives when compared to the other subtraction methods. The double phase 99mTc-sestamibi method produced only 10% of all false-positive findings. The false-positive image rate (%) is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The false-positive image rate (%) for each image set and each physician.

| Physician | False-positive rate (%) for image set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 17.9 |

| 2 | 12.5 | 14.3 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 11.5 |

| 3 | 9.5 | 11.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 |

| 4 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| Average | 9.6 | 11.5 | 13.3 | 0.0 | 9.0 |

3.5. False-Negative Findings

There was only one abnormal parathyroid gland (number 10, Table 1) that was visualized in all image sets and by all of the physicians. Thus 23 patients had 29 different false-negative findings (267 false-negative findings if all physicians and image sets are summed up). 99mTc-sestamibi/123I subtraction planar images with parallel-hole collimator produced 13.9% of all false-negative findings, 99mTc-sestamibi/123I subtraction planar images with pinhole collimator produced 9.7% of all false-negative findings, 99mTc-sestamibi double phase images with parallel-hole collimator produced 22.8% of all false-negative findings, 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT produced 39.3% of all false-negative findings, and 99mTc-sestamibi/123I subtraction SPECT/CT produced 14.2% of all false-negative findings (all physicians and all image sets are summed up).

The smallest gland located in this series was 260 mg. There were three smaller abnormal parathyroid glands (160 mg, 170 mg, and 200 mg) that could not be located with any method or imaging technique by any of the physicians. The mean gland size of false-negative and true-positive findings for all physicians and image sets are presented in Table 6 together with the statistical significance.

Table 6.

The mean gland size of false-negative and true-positive findings for all physicians and all image sets.

| Image set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Smallest gland visualized | 260 | 260 | 420 | 550 | 260 |

| Mean weight of FN (mg) | 300 | 420 | 485 | 420 | 300 |

| Mean weight of TP (mg) | 560 | 570 | 960 | 830 | 560 |

| P (FN versus TP) | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.026 | <0.001 |

3.6. Interobserver Variability

The κ coefficient for the agreement of the results between the four physicians for the five study readings are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

The comparison of reader agreement (accuracy and sensitivity) between physicians.

| κ coefficient for | Physicians | Image set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Accuracy | 1 versus 4 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.97 | 0.62 |

| 1 versus 3 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.97 | 0.56 | |

| 1 versus 2 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.59 | 0.92 | 0.69 | |

| 4 versus 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.91 | |

| 4 versus 2 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.59 | |

| 3 versus 2 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.53 | |

|

| ||||||

| Sensitivity |

1 versus 4 | 0.44 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 0.84 | 0.69 |

| 1 versus 3 | 0.44 | 0.90 | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.57 | |

| 1 versus 2 | 0.56 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.81 | |

| 4 versus 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.86 | |

| 4 versus 2 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.69 | |

| 3 versus 2 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.57 | |

The highest agreement for accuracy was found for 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT, which did not have any false-positive findings for any physician. The highest agreement for sensitivity was found for the planar subtraction images of 123I/99mTc-sestamibi with the pinhole collimator.

4. Discussion

Our results clearly show that a dual-tracer method with 99mTc-sestamibi and 123I is superior to a single-tracer method with 99mTc-sestamibi for PS, regardless of the acquisition technique used. This has been proposed by other authors as well [4, 9, 13, 14].

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing planar imaging with parallel-hole and pinhole collimators using the 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction method with patients. We could not demonstrate the improved sensitivity from the use of the pinhole collimator that has been shown by several authors when using 99mTc-sestamibi [15–20].

SPECT alone has been shown to improve sensitivity compared with planar imaging with parallel-hole collimators [6, 21–24]. SPECT/CT has been shown to offer precise anatomical localization and an improvement in diagnostic specificity and accuracy over conventional SPECT, especially for patients with previous neck surgery or multiglandular disease [5, 25–32]. The use of SPECT/CT also shortens surgical times (when compared with SPECT alone) and eventually lowers costs [33, 34]. Opposite opinions have also been presented, and the use of SPECT/CT has been found to be important only for locating ectopic parathyroid adenomas [35, 36].

We could not demonstrate an increased sensitivity for 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT when compared with planar 99mTc-sestamibi/123I subtraction image sets. However, the use of 123I/99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT decreased the false-positive rate for three observers when compared with planar 123I/99mTc-sestamibi image sets.

The low sensitivity of double phase planar 99mTc-sestamibi or 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT cannot be explained by the rapid washout of 99mTc-sestamibi, as 19 enlarged parathyroid glands were visible in 123I/99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT images that could not be visualized with 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT. A low sensitivity for a single tracer or the double phase protocols has also been reported by other authors [3, 37].

The low sensitivity of the 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT in this study could not be linked to the timing of the acquisition. SPECT acquisition was started approximately one hour after 99mTc-sestamibi injection. Lavely and coworkers were able to demonstrate much better sensitivity for early-phase SPECT/CT (62%) and also for early planar/delayed planar imaging (56,5%) [5]. The timing of their early planar and SPECT/CT acquisitions was almost identical to ours.

Our results for the 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT are comparable to the results of Neumann and coworkers [26], who demonstrated a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 96% in a group of 61 patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. The increase of specificity (when compared with SPECT alone) was explained by reducing the number of false positives.

There were three abnormal parathyroid glands that were visible in 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction planar images (with a parallel-hole or a pinhole collimator) but not visible in 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT. This could be due to rapid washout [38] as SPECT/CT was performed one hour later than the planar images were acquired. Thus, the timing of the various acquisitions should be considered carefully, and SPECT/CT should be performed in the early phase so as not to miss abnormal parathyroid gland(s) with rapid washout [10].

The average false-positive rate was comparable to previous reports [6, 11]. In this retrospective study, the five image sets were not reviewed together, which is normally done in our clinical scenario. With careful observation of the 123I images of the thyroid, it should be possible to decrease the false-positive rate in subtraction images.

It seems that a major factor influencing detection of abnormal parathyroid glands is their size. The difference of mean gland size of false-negative and true-positive findings was statistically significant for all protocols used in this study.

There was lower number of ectopic glands in this patient group than could be expected [39]. There might have been small ectopic glands which were not recognized in scintigraphy or in surgery. This might explain the slightly elevated iPTH values for 7 patients.

Several imaging protocols for PS with 99mTc-sestamibi are in use, with a wide range of sensitivities (34–100%) reported [8]. No large study exists that compares the accuracy of each [6]. We have shown the superiority of the 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction method of PS. The high popularity of the single-tracer method with 99mTc-sestamibi alone can only be explained by its technical simplicity. It is true that the 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction method, especially SPECT/CT, is technically demanding. There are several possible sources of artifacts, such as scaling and the subtraction process. In our opinion, the data processing should be performed by an experienced medical physicist.

Even optimal processing of identical 99mTc and 123I targets does not give flawless subtraction image, some activity is always left around the edges. In this series, it was in few cases interpreted as a positive finding. To our knowledge, this artefact has not been described earlier concerning parathyroid scintigraphy [40].

The overall interobserver agreement in this study was good. The average κ coefficient was 0.79 for accuracy and 0.70 for sensitivity. These results are comparable to previous results [12, 15].

One of the main limitations of this study is the number of patients in the image set 3 (99mTc-sestamibi double phase images). Another limitation of our study relates to the fact that the delay phase was acquired with another gamma camera. However, quality assurance measurements are routinely performed for both cameras. There are no differences in important parameters regarding image quality.

The clinical PS protocol presented in this study, which included various acquisitions, is quite time consuming. The discomfort for the patient should be decreased by rejecting unnecessary acquisitions. This study indicates that the 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction method combined with any imaging technique is adequate to locate abnormal parathyroid glands. However, 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT is recommended because it provides accurate three-dimensional information about the location of enlarged parathyroid adenomas together with anatomical information (Figure 3) and may influence the surgical approach [14]. With SPECT/CT, it is also possible to avoid some false-positive findings resulting from the 99mTc-sestamibi uptake in bone structures. The additional use of anterior pinhole images may be useful for recognizing cold thyroid nodules and thus further reducing the false-positive rate. Determining the optimal technical aspects (acquisition and processing parameters, various physical corrections) still requires further study.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study show that the 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction method combined with any imaging technique is superior for enlarged parathyroid gland localization when compared with 99mTc-sestamibi alone with any acquisition technique. 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT/CT is recommended because it provides accurate three-dimensional information about the location of enlarged parathyroid adenomas. The use of anterior pinhole images may be useful for recognizing cold thyroid nodules and thus reducing the false-positive rate. The overall interobserver agreement for accuracy and for sensitivity in this study was good. Thus the parathyroid scintigraphy is independent of the reporter.

There are two limitations that need to be acknowledged regarding this study. The first limitation is the number of patients in the 99mTc-sestamibi double phase group. Another limitation relates to the fact that the delay phase was acquired with another gamma camera.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Department of Nuclear Medicine at Satakunta Central Hospital. This study was supported by a grant from the Research Funding of Satakunta Central Hospital (Erityisvaltionosuus). No other potential conflict of interests is reported.

References

- 1.Coakley AJ, Kettle AG, Wells CP, O’Doherty MJ, Collins REC. 99Tcm sestamibi—a new agent for parathyroid imaging. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 1989;10(11):791–794. doi: 10.1097/00006231-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumachi F, Ermani M, Basso S, Zucchetta P, Borsato N, Favia G. Localization of parathyroid tumours in the minimally invasive era: Which technique should be chosen? Population-based analysis of 253 patients undergoing parathyroidectomy and factors affecting parathyroid gland detection. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2001;8(1):63–69. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taillefer R, Boucher Y, Potvin C, Lambert R. Detection and localization of parathyroid adenomas in patients with hyperparathyroidism using a single radionuclide imaging procedure with technetium-99m-sestamibi (double-phase study) Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1992;33(10):1801–1807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann DR, Esselstyn CB, Jr., Go RT, Wong CO, Rice TW, Obuchowski NA. Comparison of double-phase 99mTc-sestamibi with 123I-99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT in hyperparathyroidism. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1997;169(6):1671–1674. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavely WC, Goetze S, Friedman KP, et al. Comparison of SPECT/CT, SPECT, and planar imaging with single- and dual-phase 99mTc-sestamibi parathyroid scintigraphy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48(7):1084–1089. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma J, Mazzaglia P, Milas M, et al. Radionuclide imaging for hyperparathyroidism (HPT): Which is the best technetium-99m sestamibi modality? Surgery. 2006;140(6):856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tunninen V, Kauppinen T, Eskola H, Koskinen MO. Parathyroid scintigraphy protocols in Finland in 2010: Results of the query and current status. NuklearMedizin. 2010;49(5):187–194. doi: 10.3413/Nukmed-0311-10-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihai R, Simon D, Hellman P. Imaging for primary hyperparathyroidism-an evidence-based analysis. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery. 2009;394(5):765–784. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceyssens S, Mortelmans L. Parathyroid imaging: basic principles and KU Leuven experience: MIBI-dual phase versus MIBI/I-123. Acta Oto-Rhino-Laryngologica Belgica. 2001;55(2):103–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hindie E, Ugur O, Fuster D, et al. 2009 EANM parathyroid guidelines. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2009;36(7):1201–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1131-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hindié E, Mellière D, Jeanguillaume C, Perlemuter L, Chéhadé F, Galle P. Parathyroid imaging using simultaneous double-window recording of technetium-99m-sestamibi and iodine-123. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1998;39(6):1100–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalar C, Ozdogan O, Durak MG, et al. Inter-observer and intra-observer agreement in parathyroid scintigraphy; what can be done for making parathyroid scintigraphy more reliable? Endocrine Practice. 2012:1–32. doi: 10.4158/EP11330.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Doherty MJ, Kettle AG. Parathyroid imaging: preoperative localization. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2003;24(2):125–131. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taieb D, Hindie E, Grassetto G, Colletti PM, Rubello D. Parathyroid scintigraphy: when, how, and why? A concise systematic review. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2012;37:568–574. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318251e408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arveschoug AK, Bertelsen H, Vammen B. Presurgical localization of abnormal parathyroid glands using a single injection of Tc-99m sestamibi comparison of high-resolution parallel-hole and pinhole collimators, and interobserver and intraobserver variation. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2002;27(4):249–254. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arveschoug AK, Bertelsen H, Vammen B, Brøchner-Mortensen J. Preoperative dual-phase parathyroid imaging with Tc-99m-sestamibi: accuracy and reproducibility of the pinhole collimator with and without oblique images. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2007;32(1):9–12. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000249401.48030.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dontu VS, Kettle AG, O’Doherty MJ, Coakley AJ. Optimization of parathyroid imaging by simultaneous dual energy planar and single photon emission tomography. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2004;25(11):1089–1093. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho Shon IA, Yan W, Roach PJ, et al. Comparison of pinhole and SPECT99mTc-MIBI imaging in primary hyperparathyroidism. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2008;29(11):949–955. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328309789e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho Shon IA, Bernard EJ, Roach PJ, Delbridge LW. The value of oblique pinhole images in pre-operative localisation with 99mTc-MIBI for primary hyperparathyroidism. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;28(6):736–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomas MB, Pugliese PV, Tronco GG, Love C, Palestro CJ, Nichols KJ. Pinhole versus parallel-hole collimators for parathyroid imaging: an intraindividual comparison. Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology. 2008;36(4):189–194. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.108.055640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorberboym M, Minski I, Macadziob S, Nikolov G, Schachter P. Incremental diagnostic value of preoperative 99mTc-MIBI SPECT in patients with a parathyroid adenoma. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;44(6):904–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moka D, Voth E, Dietlein M, Larena-Avellaneda A, Schicha H. Technetium 99m-MIBI-SPECT: a highly sensitive diagnostic tool for localization of parathyroid adenomas. Surgery. 2000;128(1):29–35. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slater A, Gleeson FV. Increased sensitivity and confidence of SPECT over planar imaging in dual-phase sestamibi for parathyroid adenoma detection. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2005;30(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas DL, Bartel T, Menda Y, Howe J, Graham MM, Juweid ME. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) should be routinely performed for the detection of parathyroid abnormalities utilizing technetium-99m sestamibi parathyroid scintigraphy. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2009;34(10):651–655. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181b591c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris L, Yoo J, Driedger A, et al. Accuracy of technetium-99M SPECT-CT hybrid images in predicting the precise intraoperative anatomical location of parathyroid adenomas. Head and Neck. 2008;30(4):509–517. doi: 10.1002/hed.20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann DR, Obuchowski NA, DiFilippo FP. Preoperative 123I/99mTc-sestamibi subtraction SPECT and SPECT/CT in primary hyperparathyroidism. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2008;49(12):2012–2017. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papathanassiou D, Flament JB, Pochart JM, et al. SPECT/CT in localization of parathyroid adenoma or hyperplasia in patients with previous neck surgery. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2008;33(6):394–397. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318170d4a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prommegger R, Wimmer G, Profanter C, et al. Virtual neck exploration: a new method for localizing abnormal parathyroid glands. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250(5):761–765. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bd906b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach PJ, Schembri GP, Ho Shon IA, Bailey EA, Bailey DL. SPECT/CT imaging using a spiral CT scanner for anatomical localization: impact on diagnostic accuracy and reporter confidence in clinical practice. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2006;27(12):977–987. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000243372.26507.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serra A, Bolasco P, Satta L, Nicolosi A, Uccheddu A, Piga M. Role of SPECT/CT in the preoperative assessment of hyperparathyroid patients. Radiologia Medica. 2006;111(7):999–1008. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taubman ML, Goldfarb M, Lew JI. Role of SPECT and SPECT/CT in the surgical treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism. International Journal of Molecular Imaging. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/141593.141593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wimmer G, Profanter C, Kovacs P, et al. CT-MIBI-SPECT image fusion predicts multiglandular disease in hyperparathyroidism. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery. 2010;395(1):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pata G, Casella C, Besuzio S, Mittempergher F, Salerni B. Clinical appraisal of 99mTechnetium-sestamibi SPECT/CT compared to conventional SPECT in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and concomitant nodular goiter. Thyroid. 2010;20(10):1121–1127. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pata G, Casella C, Magri GC, Lucchini S, Panarotto MB, Crea N, et al. Financial and clinical implications of low-energy CT combined with 99m Technetium-sestamibi SPECT for primary hyperparathyroidism. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2011;18:2555–2563. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gayed IW, Kim EE, Broussard WF, et al. The value of 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT over conventional SPECT in the evaluation of parathyroid adenomas or hyperplasia. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46(2):248–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruf J, Seehofer D, Denecke T, et al. Impact of image fusion and attenuation correction by SPECT-CT on the scintigraphic detection of parathyroid adenomas. NuklearMedizin. 2007;46(1):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billotey C, Aurengo A, Najean Y, et al. Identifying abnormal parathyroid glands in the thyroid uptake area using technetium-99m-sestamibi and factor analysis of dynamic structures. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1994;35(10):1631–1636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krausz Y, Shiloni E, Bocher M, Agranovicz S, Manos B, Chisin R. Diagnostic dilemmas in parathyroid scintigraphy. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2001;26(12):997–1001. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phitayakorn R, McHenry CR. Incidence and location of ectopic abnormal parathyroid glands. American Journal of Surgery. 2006;191(3):418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins AC, Whalley DR, Hardy JG. Physical approach for the reduction of dual radionuclide image subtraction artefacts in immunoscintigraphy. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 1984;5(8):501–512. doi: 10.1097/00006231-198408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]