Abstract

Purpose.

Neovascularization (NV) is a sight-threatening complication of retinal ischemia in diabetes, retinal vein occlusion, and retinopathy of prematurity. Current treatment modalities, including laser photocoagulation and repeated intraocular injection of VEGF antagonists, are invasive and not always effective, and may carry side effects. We studied the use of hyperoxia as an alternative therapeutic strategy for regressing established vitreous NV in a mouse model of oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy.

Methods.

Hyperoxia treatment (HT, 75% oxygen) was initiated on postnatal day (P)17 after the onset of vitreous NV. Immunohistochemistry and quantitative PCR were used to assess retinal vascular changes in relation to apoptosis, and expression of VEGFR2 and inflammatory molecules. Effects of intravitreal injections of VEGF-A, VEGF-E, PlGF-1, and VEGF trap were also studied.

Results.

HT selectively reduced NV by 70% within 24 hours. It robustly increased the level of cleaved caspase-3 in the vitreous NV between 6 and 18 hours and promoted infiltration of macrophage/microglial cells. The HT-induced apoptosis was preceded by a significant reduction in VEGFR2 expression within the NV and an increase in VEGFR2 within the surrounding neural tissue. Intravitreal VEGF-A and VEGF-E (VEGFR2 agonist) but not PlGF-1 (VEGFR1 agonist) prevented HT-induced apoptosis and regression of NV. In contrast, VEGF trap and VEGFR2 blockers mimicked the effect of HT. However, intravitreal VEGF trap induced increases in inflammatory molecules while HT did not have such unwanted effect.

Conclusions.

HT may be clinically useful to specifically treat proliferative NV in ischemic retinopathy.

We found that hyperoxia therapy caused rapid resolution of established vitreous neovascularization in ischemic retinopathy by downregulating the VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway.

Introduction

Ischemic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in persons under 60 years of age in the United States. It is a sight-threatening complication of diabetes, retinal vein occlusion, and retinopathy of prematurity. Retinal structure and function are compromised by cellular ischemia, increased vascular permeability and exudation, and pathological neovascularization (NV) of the vitreous, leading to hemorrhage, fibrosis, and retinal detachment. The NV is a consequence of several pathophysiological responses to ischemia, including the expression of hypoxia-induced angiogenic cytokines, inflammation, and breakdown of the limiting membrane that separates the neural retina from vitreous.

Laser photocoagulation is the most commonly employed therapy for proliferative retinopathy. However, this method destroys retinal neurons and causes side effects such as reduced visual acuity and impaired night vision.1 Anti-VEGF agents are now in widespread use for treatment of subretinal neovascularization associated with age-related macular degeneration and are being investigated in clinical trials for diabetic retinopathy.2 Although anti-VEGF therapy is not destructive and the majority of patients experience no adverse events, it is not always effective and there are concerns about the long-term safety of VEGF antagonism.3 Suppression of VEGF-mediated cell survival pathways in neurons and Müller cells could impair their survival and/or alter their function.4,5 Specifically eliminating VEGF in retinal pigmented epithelial cells leads to loss of the choriocapillaris, dysfunction of cone photoreceptors, and vision loss.3 Further, the delivery of antiangiogenic agents by intravitreal injection also carries a significant risk of iatrogenic complications, including endophthalmitis, hemorrhage, and cataract.6,7 Therefore, there is a need to develop an alternative approach to treat NV in ischemic retinopathy either by itself or in combination with anti-VEGF therapy in order to maximize the effectiveness while minimizing the side effects.

The therapeutic use of oxygen has been extensively studied as a strategy for improving wound healing,8 especially in clinical situations where tissue perfusion is compromised by arterial insufficiency,9 diabetes,10,11 or prior radiation treatment for neoplasia.12 Numerous studies support the use of hyperbaric oxygen as adjunctive treatment for nonhealing lower extremity wounds in diabetics,10,11 compromised tissue flaps and grafts,13 and radiation-induced ischemic osteonecrosis.14 Experiments in various animal models of ischemia have suggested that supplemental oxygen can improve the rate of wound healing as well as reduce apoptosis in the affected tissue.8

The therapeutic effects of oxygen supplementation in ischemic retinopathy have not been well characterized. However, it has been shown that hyperoxia treatment preserves retinal neuronal function during retinal arterial occlusion15 and reduces breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats.16 Supplemental oxygen prior to the development of NV has been shown to markedly reduce the subsequent development of pathological NV in animal models of oxygen-induced retinopathy.17–19 In humans, small case series have suggested that normobaric supplemental oxygen can reduce vascular permeability and retinal thickness in diabetic macular edema20 and central retinal vein occlusion.21,22 These clinical and scientific studies support the potential value of oxygen therapy as a primary or adjunctive treatment for vision-threatening ischemic retinopathies.

Because vitreous NV is the major course of blindness in ischemic retinopathy, in this study we investigated whether supplemental oxygen would be effective in eliminating established NV. Our experiments in a murine model of ischemic retinopathy demonstrate that hyperoxia therapy (HT) causes rapid apoptosis and regression of vitreous NV, but without any apparent adverse side effects. This contrasted with the use of VEGF-trap, which also caused rapid apoptosis of NV, but induced a retinal inflammatory response. Our study further indicates that the beneficial effect of HT on NV is mediated by downregulation of signaling through the VEGFR2 pathway.

Methods

Treatment of Animals

All procedures with animals were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (Animal Welfare Assurance no. A3307-01). A mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) was induced as previously described.23 In brief, at postnatal day (P)7, mouse pups along with nursing mothers were placed in 75% oxygen. At P12, they were returned to room air (21% oxygen) for 5 days until P17. This is a model of ischemic retinopathy because obliteration of the immature retinal vessels is induced during the exposure to 75% oxygen from P7 through P12. Immediately upon return to room air, the avascular central retina becomes hypoxic, leading to significant vitreous NV that peaks at P17. To investigate the effect of HT, OIR mice were exposed to 75% oxygen for 3 to 24 hours at P17 (HT groups) or kept in room air as room air controls (RA). At the end of treatment, the mice were sacrificed and their eyes or retinas were prepared for morphology or molecular biology studies.

Intravitreal Injection

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of avertin (625 mg/kg). Intravitreal injections were performed by delivering 0.5 μL PBS containing 20 to 200 ng mouse VEGF-A (VEGFR1/2 agonist); 300 ng human PlGF-1 (VEGFR1 agonist); 2 μg VEGF trap (VEGFR1/Fc, VEGF blocker; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN); 300 ng VEGF-E (VEGFR2 agonist; Cell Sciences, Canton, MA); 25 μg VEGFR2 inhibitory peptide (VEGFR2 blocker; AnaSpec, Fremont, CA); 50 pmol VEGFR2 siRNA (to reduce VEGFR2 expression) or 50 pmol control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); or vehicle (PBS) with only a 35-gauge needle mounted to a 10-μL Hamilton syringe. The tip of the needle was inserted under the guidance of a dissecting microscope (Leica Wild M650; Leica, Bannockburn, IL) through the dorsal limbus of the eye. Injections were performed slowly over a period of 2 minutes.

Immunostaining of Whole-Mount Retinas

Immunostaining was performed as previously described.19 Briefly, eyes were removed at indicated time points and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The cornea, sclera, lens, vitreous, and hyaloid vessels were removed and radial incisions were made along the retinal edge at equal intervals. Subsequently retinas were blocked and permeabilized in PBS containing 5% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton-X-100 (1 hour). Primary antibodies (cleaved caspase-3 [1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA]); NG2 (1:200; Millipore, Billerica, MA); VEGFR2 (1:200; R&D systems) were co-stained with Alex594-labeled isolectin B4 (Griffonia simplicifolia, 1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Retinas were flatmounted in mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and examined by fluorescence microscopy (Axiophot; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) and by confocal microscopy (Zeiss 510; Carl Zeiss). Areas of vasoobliteration and vitreoretinal neovascular tufts were quantified using an analysis of digital images (ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) of retinal flatmounts stained with isolectin B4 as previously reported.24

Immunostaining on Retinal Sections

Eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, equilibrated in 30% sucrose, embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and cut into 10-μm sections. Retina sections were permeabilized with PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 (30 minutes) and blocked with 3% normal donkey serum (30 minutes). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-VEGFR2 antibody and biotin-labeled isolectin B4. After washing in PBS, sections were incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibody at 1:400 (Invitrogen) and AMCA-labeled avidin (Vectashield, 1 hour), washed with PBS, covered in mounting medium under a coverslip, and examined by fluorescence microscopy (Carl Zeiss).

Isolation of Retinal Vessels

Retinal vessels were selectively isolated from other components of the retina using a procedure modified from the those described previously.25,26 Briefly, retinas were dissected and incubated in ice-cold sterile water (1 hour, 4°C). The preparation was then transferred to a 60-mm dish containing 500 U DNase I (Worthington Biochemical Corp.) in 4 mL distilled water for 10 minutes. During the incubation, the DNase solution was gently and repeatedly pipetted on the tissue until the preparation looked transparent. The preparation was transferred back to water and microvascular networks were separated from debris. The purity of the isolated vessels was assessed by microscopic examination after staining the vessels with periodic acid-schiff and hematoxylin.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse whole retinas or retinal vasculature using an RNA purification kit (RNAqueous-4PCR; Invitrogen), and reverse-transcribed with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) to generate cDNA.19 Quantitative PCR was performed using a real-time PCR system (StepOne PCR; Applied Biosystems) with Power SYBR Green. The relative difference in various transcripts was calculated by the CT method using Hprt as the internal control. After PCR, a melting curve was constructed in the range of 60°C to 95°C to evaluate the specificity of the amplification products. Primer sequences for mouse transcripts were as follows: Hprt For-5′-GAA AGA CTT GCT CGA GAT GTC ATG-3′; Hprt Rev-5′-CAC ACA GAG GGC CAC AAT GT-3′; MCP-1 For-5′-GGC TCA GCC AGA TGC AGT TAA-3′; MCP-1 Rev-5′-CCT ACT CAT TGG GAT CAT CTT GCT-3′; TNF-α For-5′-GGT CCC CAA AGG GAT GAG AA-3′; TNF-α Rev-5′-TGA GGG TCT GGG CCA TAG AA −3′; CD11b For-5′-AAA CCA CAG TCC CGC AGA GA-3′; CD11b Rev-5′-CGT GTT CAC CAG CTG GCT TA-3′; ICAM-1 For-5′-CAG TCC GCT GTG CTT TGA GA-3′; ICAM-1 Rev-5′-CGG AAA CGA ATA CAC GGT GAT-3.′

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Group differences were evaluated by using one way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Student's t-test. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

HT Induces Rapid Regression of Established Vitreous NV

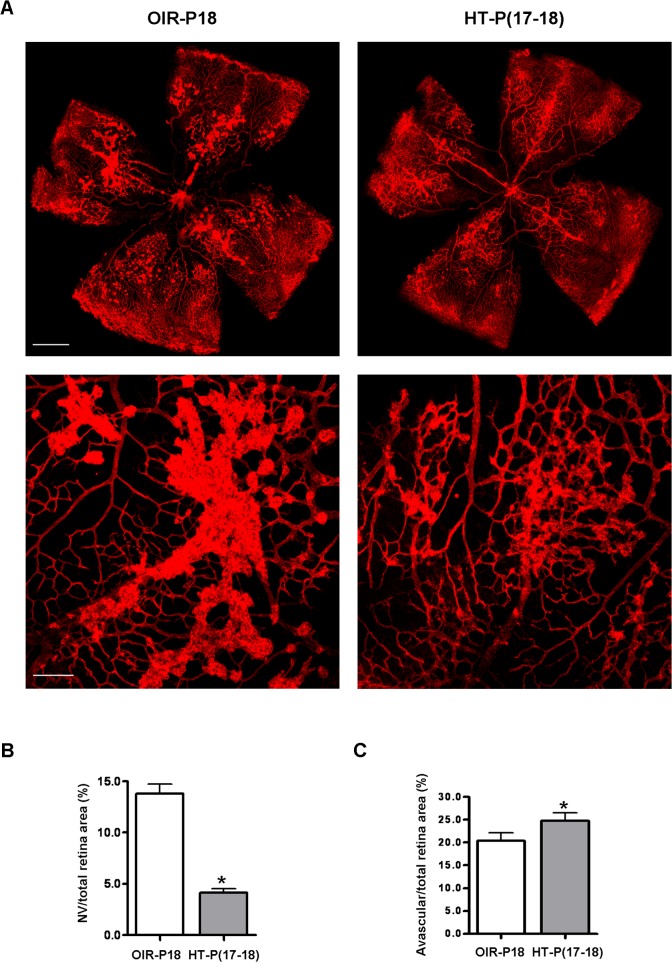

Studies were performed in the mouse model of ischemic retinopathy. This mouse model has been extensively utilized as a model of ischemia-induced NV to mimic the proliferative stage of retinopathy of prematurity, diabetic retinopathy, and retinal vein occlusion. Although it has limitations, it has been widely used for studies of mechanisms and strategies for blockade of pathological NV.23,27–31 Most have looked at interventions initiated prior to the development of NV and may therefore be considered preventive approaches. Relatively few studies have investigated approaches aimed at resolving established vitreous NV, which is the major cause of blindness in ischemic retinopathy. Here we evaluate the effects of HT on established pathogenic neovascularization. Mice with OIR were treated on P17 with either HT (75% O2) or room air for 24 hours. Following treatment, analysis of the areas of vitreous NV and avascular area revealed that HT reduced the total area of vitreous NV by approximately 70%, while only slightly increasing the avascular area, compared with untreated controls (Figs. 1A–C). These results demonstrate that the effects of HT are relatively selective in targeting pathological NV while leaving existing intraretinal vessels largely intact.

Figure 1. .

Hyperoxia treatment induces regression of NV tufts in OIR. OIR mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) for 24 hours from P17 to P18 or maintained in room air (OIR). (A) Retinal vessels were stained with isolectin B4 at P18. Upper panel: representative images of retinal flatmounts. Scale bar, 500 μm. Lower panel: high magnification images of NV area taken at 100× by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) NV areas and (C) avascular areas were quantified (n = 8 mice). *P < 0.05 compared with OIR.

HT Causes Apoptosis of Pathological NV and an Influx of Macrophages/Microglia

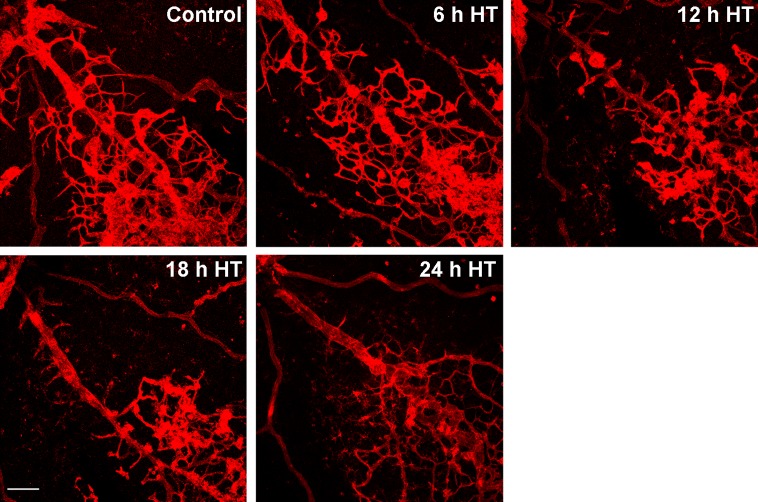

We reasoned that the HT-induced NV resolution had to occur by one of two processes: by endothelial cells (ECs) becoming disassociated from the NV tufts and migrating away or by apoptosis. To test this possibility, we examined the time course of HT-induced regression and found that regression of vitreous NV is apparent at 12 hours and virtually complete by 24 hours after HT (Fig. 2). Upon careful analysis of lectin-labeled flatmounts at high magnification, we were unable to detect EC migration away from NV tufts within the time period from 6 to 24 hours after HT, suggesting that regression of NV is not caused by cellular disassembly of the capillaries.

Figure 2. .

Regression of NV by hyperoxia is apparent at 12 hours and virtually complete at 24 hours. OIR mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) at P17 for 6 to 24 hours. Retinal vessels were stained with isolectin B4 and images were taken at ×100 by confocal microscopy. Representative images show the regression of NV tufts over time (n = 3 mice at each time point). Scale bar, 100 μm.

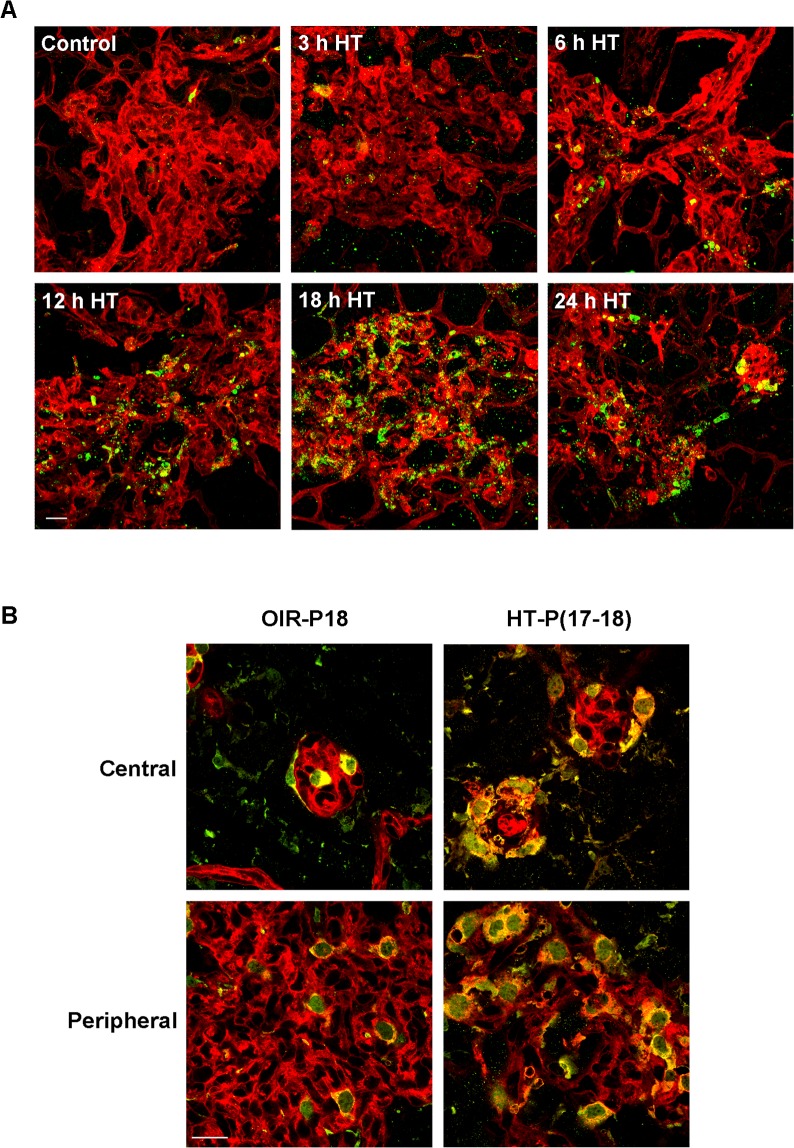

We next examined the potential role of apoptosis in the HT-induced NV regression. Activation of cysteine proteases, especially caspase-3, is a common feature involved in the execution of apoptosis.32 We therefore used immunolabeling techniques to determine the level of cleaved caspase-3 (active caspase-3) in whole mount retinas. This analysis showed that immunoreactivity for cleaved caspase-3 was localized to vitreous NV after 6 hours of HT, and was maximal at 18 hours (Fig. 3A). High-magnification imaging showed that cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was present in pyknotic nuclei (see Supplementary Material and Supplementary Fig. S1, http://www.iovs.org/content/54/2/918/suppl/DC1), indicating that the cleaved caspase-3 positive cells were undergoing apoptosis. The observed apoptosis of NV-associated endothelial cells was accompanied by an infiltration of macrophages/microglia, which were identified by their Iba-1 and isolectin B4 positive labeling (Fig. 3B). These phagocytic cells are extremely proficient in the removal of cell debris and are required for normal tissue repair. This result demonstrates that HT induces NV resolution by causing the apoptosis of endothelial cells, which is followed by clearance of the dead cells by microphage/microglia.

Figure 3. .

Hyperoxia treatment induces apoptosis in NV tufts and recruitment of macrophage/microglia. OIR mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) for 3 to 24 hours at P17. (A) Retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red) and anti-cleaved caspase-3 (green). Representative confocal images of NV tufts are shown (400×, n = 3 mice at each time point). Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Retinal flatmounts were costained with isolectin B4 (red) for vessels and activated macrophage/microglia, and anti-Iba1 (green) for macrophage/microglia. Representative confocal images of NV tufts are shown (×630, n = 3 mice). Scale bar, 20 μm.

HT Induces Endothelial Cell Apoptosis via Downregulation of the VEGF-Dependent Survival Pathway

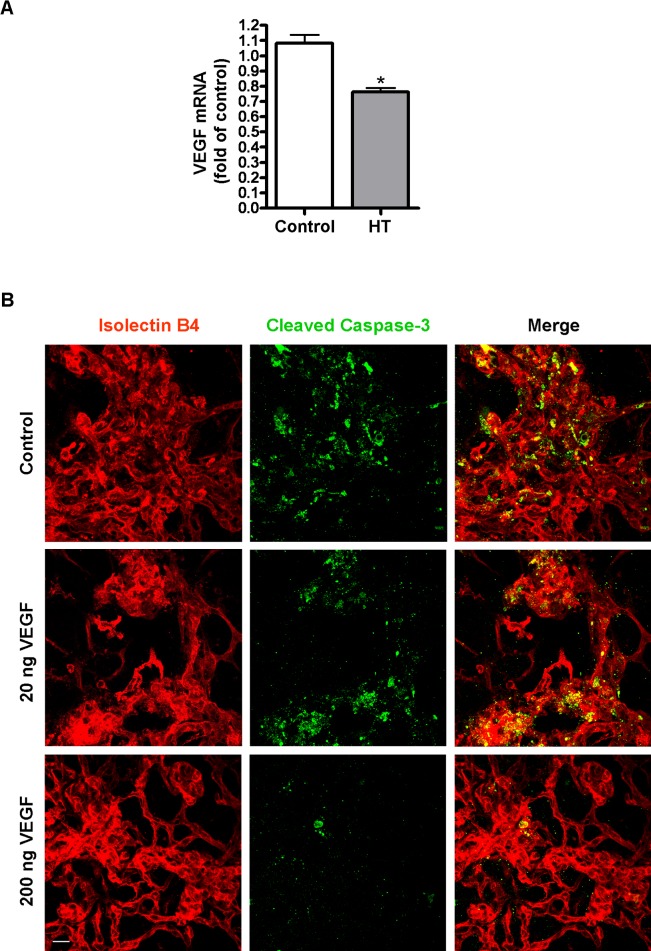

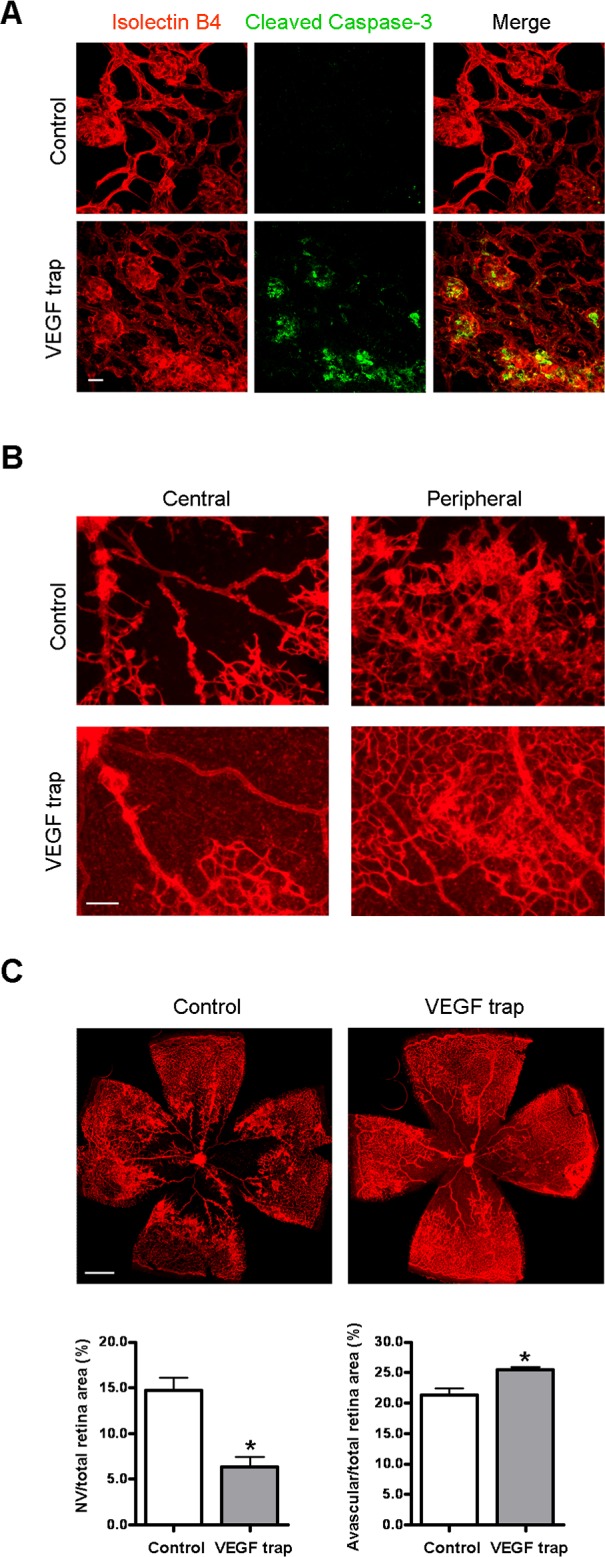

VEGF is an important endothelial cell survival factor. Downregulation of VEGF by hyperoxia has been implicated as an important mechanism of retinal vessel obliteration in retinopathy of prematurity.33 To investigate whether this mechanism is responsible for HT-induced NV regression, quantitative PCR was performed to analyze VEGF mRNA following HT. Our data show that VEGF was decreased by 30% following HT (Fig. 4A). To further explore whether HT-induced decrease in VEGF is involved in the regression of NV, we compensated loss of VEGF with exogenous VEGF-A given by intravitreal injection prior to HT and evaluated its rescue effect of NV regression. Alternatively, we directly blocked VEGF signaling with a VEGF trap and determined whether it would cause a similar effect as HT. VEGF trap is a soluble fusion protein composed of a modified VEGF-binding domain of VEGFR1/Flt-1 receptor and the IgG Fc fragment. It potently binds all isoforms of VEGF and PlGF-1, preventing them from binding to VEGF receptors. As shown in Figure 4B, intravitreal VEGF-A (200 ng/eye) caused a significant reduction in HT-induced regression and apoptosis of NV. This rescue effect was not seen with a lower dose of VEGF-A (20 ng/eye). In contrast to the survival effect of exogenous VEGF, intravitreal delivery of a VEGF trap at P17 caused rapid apoptosis and regression of pathological NV by P18 at a magnitude similar to that observed with HT (Figs. 5A–C). These studies confirm the role of VEGF as an important survival factor for NV and suggest that the effect of HT is mediated, at least in part, through downregulation of VEGF.

Figure 4. .

VEGF supplement prevents hyperoxia-induced NV apoptosis in OIR mice. (A) OIR mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) or room air (control) for 24 hours at P17. VEGF mRNA in the retinas was quantified by qPCR (n = 6 mice). *P < 0.05 compared with control. (B) OIR mice were intravitreally injected with PBS (control) or VEGF (20 ng/eye or 200 ng/eye) at P17 and then treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen) for 18 hours. Retinal vessels (isolectin B4, red) and apoptotic cells (cleaved caspase-3, green) in flatmounts were shown (×400, n = 3 mice). Scale bar, 20 μm.

Figure 5. .

Blockade of VEGF induces NV apoptosis and regression. OIR mice were intravitreally injected with PBS (control) or VEGF trap (VEGFR1/Fc, 2 μg/eye) at P17. (A) At 18 hours postinjection, retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red) and cleaved caspase-3 (green). Representative confocal images of NV tufts and cleaved caspase-3 are shown (×400, n = 4 mice). Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) At 24 hours postinjection, retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red). Representative images of NV area (×100) are shown. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Representative images of retinal flatmounts are shown. NV areas and avascular areas were quantified (n = 6 mice). Scale bar, 500 μm. *P < 0.05 compared with relevant control.

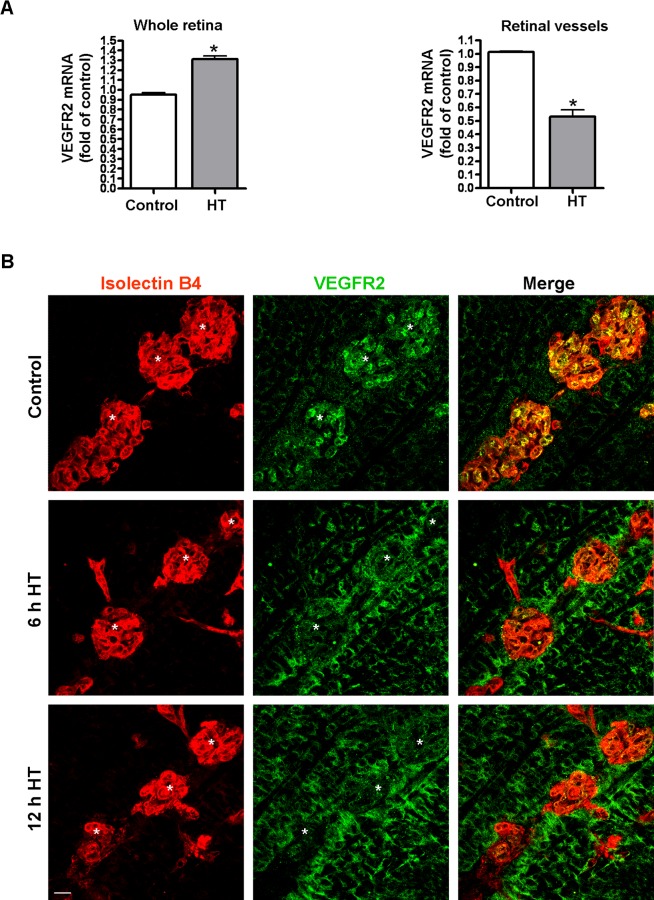

Robust VEGFR2 Expression in Vitreous NV Tufts Is Downregulated by HT

Although exogenous VEGF can rescue HT-induced NV apoptosis, a relatively large amount of VEGF is necessary to achieve this effect (Fig. 4B). This observation suggested that other elements in the VEGF pathway may also serve as a downstream target of HT and prompted us to investigate whether VEGFR2, the major receptor mediating the biological effects of VEGF,34 is altered by HT. Surprisingly, analysis of VEGFR2 mRNA expression in the whole retina revealed that the level of VEGFR2 was not decreased, but rather was increased by 38% in the hyperoxia-treated retinas (left panel, Fig. 6A). Because VEGFR2 is expressed in both vascular cells and neurons, measurements made in the whole retina may not reflect VEGFR2 levels within the retinal vessels. Thus, we isolated retinal vessels from OIR mice treated with room air (control) or HT and measured VEGFR2 mRNA expression. Microscopic examination showed a minimal amount of contamination by nonvascular cells (data not shown). The procedure significantly enriched the vascular cells and allowed us to specifically analyze molecular changes that were masked by the large amount of nonvascular cells in the whole retina. In contrast to the whole retina, VEGFR2 mRNA expression in the retinal vasculature was significantly decreased by 48% in hyperoxia-treated retinas as compared with control (right panel, Fig. 6A). This observation was confirmed by immunostaining of retinal flatmount preparations. As shown in Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure S2A (see Supplementary Material and Supplementary Fig. S2A, http://www.iovs.org/content/54/2/918/suppl/DC1), VEGFR2 expression was much higher in the vitreous NV than in the intraretinal capillaries in either the central or peripheral retina. Hyperoxia treatment caused a rapid decrease in VEGFR2 in the vitreous NV, while simultaneously increasing its expression in non-vascular cells in the inner retina, including Müller glia (see Fig. 6B and Supplementary Material and Supplementary Fig. S2A, http://www.iovs.org/content/54/2/918/suppl/DC1). To confirm these findings, we examined VEGFR2 protein localization in retinal cross-sections. This analysis showed a pattern consistent with results shown in the flatmount images (see Supplementary Material and Supplementary Fig. S2B, http://www.iovs.org/content/54/2/918/suppl/DC1). To evaluate whether the HT-induced downregulation of VEGFR2 expression is unique to the pathological condition, normal mice were exposed to hyperoxia at P17 for 12 hours and the expression of VEGFR2 was examined. The HT had no effect on VEGFR2 expression (Fig. 7). These experiments imply that hyperoxia can regulate VEGFR2 expression in ischemic retinal tissue but not in normal retinas.

Figure 6. .

Hyperoxia treatment differentially regulates VEGFR2 expression in NV and neural retina. (A) OIR mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) for 24 hours at P17. VEGFR2 mRNA in the retinas (left panel) and pooled retinal vessels (right panel) were quantified by qPCR and normalized to OIR mice kept in room air (control; n = 4 to 6 mice). *P < 0.05 compared with control. (B) OIR mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) for 6 and 12 hours at P17 and retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red) and anti-VEGFR2 (green). Representative confocal images of NV tufts (marked with white asterisk) in the central retina are shown (×400, n = 4 mice). Scale bar, 20 μm.

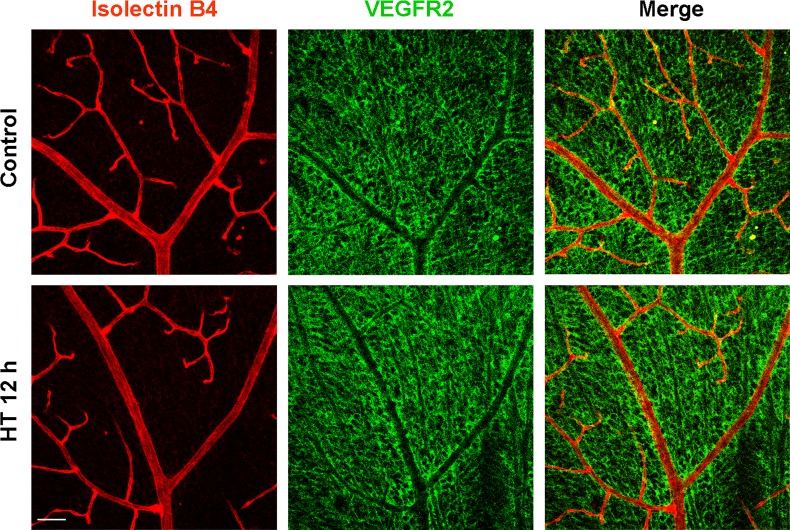

Figure 7. .

Hyperoxia treatment does not alter VEGFR2 expression in normal retinas. Normal mice were kept in room air or treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen, HT) for 12 hours at P17. Retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red) and anti-VEGFR2 (green). Representative confocal images of retinal vessels are shown (×200, n = 3 mice). Scale bar, 50 μm.

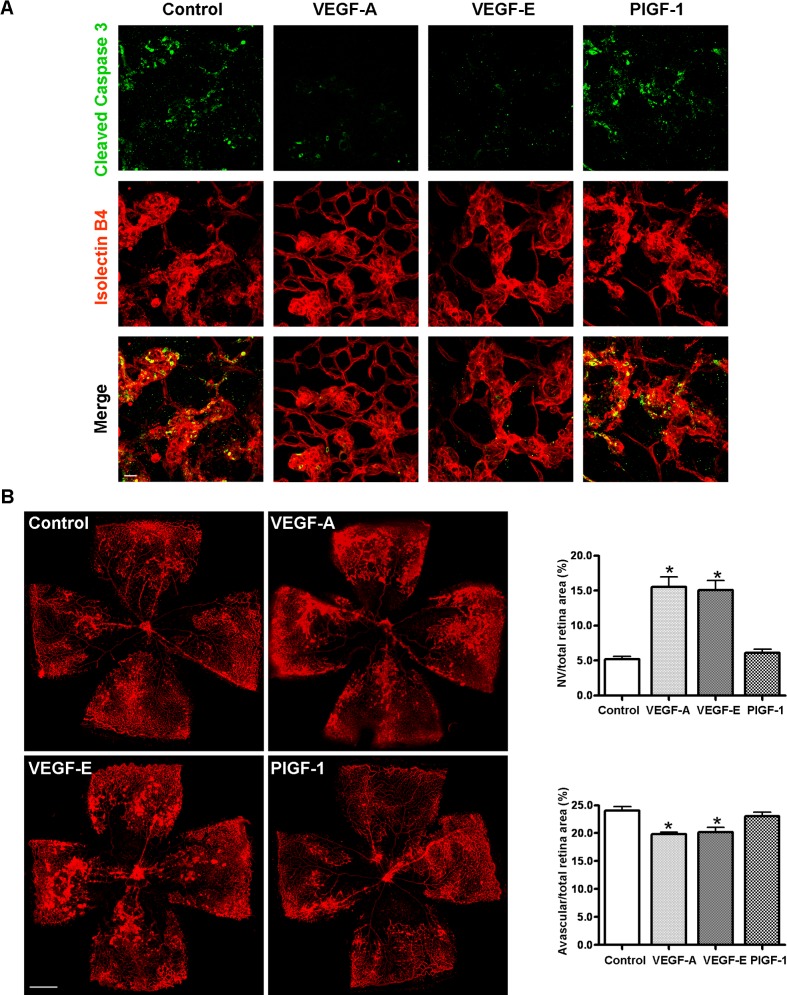

VEGFR2 Activation Protects against HT-Induced Regression of Vitreous NV

In spite of the massive reduction of VEGFR2 in the vitreous NV at 6 hours after HT, apoptosis was barely detectable (see Supplementary Material and Supplementary Fig. S3, http://www.iovs.org/content/54/2/918/suppl/DC1) and did not reach a peak until 18 hours (Fig. 3), indicating that the HT-induced downregulation of VEGFR2 in the NV precedes apoptosis. In order to specifically determine the role of the VEGFR2 signaling pathway in HT-induced regression of retinal NV, we selectively induced VEGFR2 activation by intravitreal administration of the VEGFR2-specific ligand VEGF-E and determined HT-induced NV apoptosis and regression. If downregulation of VEGFR2-mediated survival pathway was involved in HT-induced NV regression, specific activation of VEGFR2 with VEGFR-E was expected to be protective in this process. As controls, VEGF-A, a ligand for both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, and placental growth factor-1 (PlGF-1), a specific ligand for VEGFR1, were also administered and their effects were compared with that of VEGF-E (Fig. 8). We found that HT-induced apoptosis and regression of NV could be effectively prevented by prior intravitreal injection of VEGF-E or VEGF-A, but not by PlGF-1. There was no difference between the VEGF-E– and VEGF-A–treated groups. These experiments indicated that VEGF-induced endothelial cell survival in NV tufts is dependent on the activation of the VEGFR2 pathway and not the VEGFR1 pathway.

Figure 8. .

Activation of VEGFR2 but not VEGFR1 prevents HT-induced NV apoptosis and regression. OIR mice were intravitreally injected with PBS (control); VEGF-A (200 ng/eye); VEGF-E (300 ng/eye); or PlGF-1 (300 ng/eye) at P17, and 1 hour postinjection, mice were treated with hyperoxia (75% oxygen). (A) Mice were treated with hyperoxia for 18 hours and retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red) and cleaved caspase-3 (green). Representative confocal images of NV tufts are shown (×400, n = 4 mice); Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Mice were treated with hyperoxia for 24 hours and retinal flatmounts were stained with isolectin B4 (red). NV areas and avascular areas were quantified (n = 4 to 6 mice). Scale bar, 500 μm. *P < 0.05 compared with relevant control.

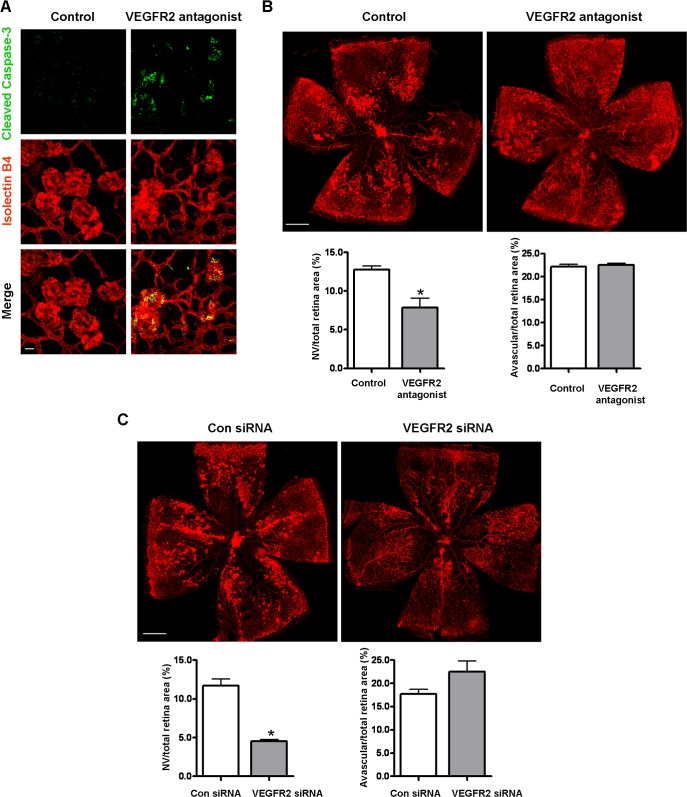

VEGFR2 Blockade Is Sufficient to Induce the Regression of Vitreous NV

To further explore the role of VEGFR2 in NV survival, we directly blocked VEGFR2 activity and determined whether such blockade would mimic the effect of HT. VEGFR2 activity was blocked with a specific inhibitory peptide, which has been shown to specifically bind to VEGFR2 and completely block binding of native VEGF to prevent VEGF-induced angiogenesis in vivo.35 Similar to HT, the administration of the VEGFR2 inhibitor peptide caused rapid apoptosis and regression of vitreous NV within 24 hours (Figs. 9A, 9B). To further confirm these results, VEGFR2 expression was knocked down by intravitreal injection of specific siRNA. Scrambled siRNA was used as a control. Consistent with the experiments using inhibitors, apoptosis of NV tufts was induced and the total area of vitreous NV was attenuated at 36 hours following the injection of VEGFR2 siRNA (Fig. 9C). These results provide further evidence that the VEGFR2 receptor mediates the critical signaling pathway for survival of pathological NV.

Figure 9. .

Blockade of VEGFR2 is sufficient to induce the apoptosis and regression of NV tufts. (A) OIR mice were intravitreally injected with PBS (control) or VEGFR2 inhibitory peptide (VEGFR2 antagonist, 25 μg/eye) at P17. At 18 hours postinjections, retinas were collected and stained with isolectin B4 (red) and cleaved caspase-3 (green). Representative confocal images of NV tufts are shown (×400, n = 3 mice). Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) At 24 hours postinjections, retinas were collected and stained with isolectin B4 (red). Representative images of retinal flatmounts are shown. Scale bar, 500 μm. NV areas and avascular areas were quantified (n = 4 mice). *P < 0.05 compared with control. (C) OIR mice were intravitreally injected with control siRNA (Con siRNA) or VEGFR2 siRNA (50 pmol/eye) at P17. At 36 hours posttreatment, retinas were collected and stained with isolectin B4 (red). Representative images of retinal flatmounts are shown. Scale bar, 500 μm. NV areas and avascular areas were quantified (n = 6 mice). *P < 0.05 compared with control.

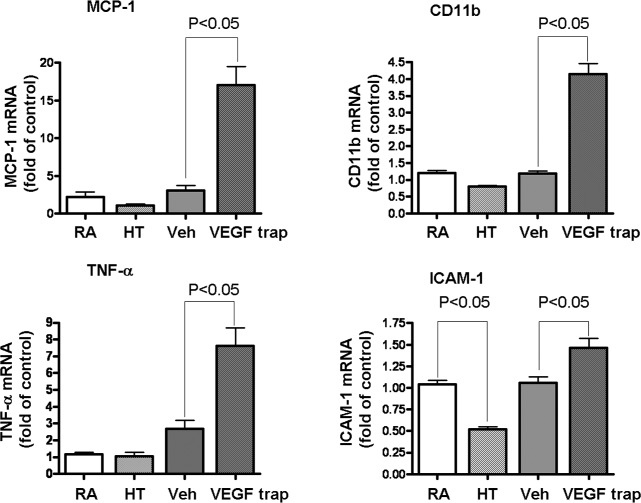

HT Is Noninflammatory

Ischemic retinopathy is associated with increased expression of numerous inflammatory mediators,19 which are thought to play a key role in the vascular pathology. Although both HT and nonselective blockade of VEGF with VEGF trap were equally effective in inducing NV regression (Figs. 1, 5), quantitative RT-PCR analysis of inflammatory mediators after treatment with HT or VEGF trap revealed that VEGF trap induced significant increases in expression of MCP-1, CD11b, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 (Fig. 10). In contrast to VEGF trap, HT did not enhance but rather reduced these inflammatory mediators. These studies suggest that HT can regress HT without the risk of inflammatory reactions.

Figure 10. .

VEGF trap, but not hyperoxia treatment induces retinal inflammation. OIR mice were either kept in room air (RA) or treated with hyperoxia therapy (HT), intravitreal PBS (Veh), or VEGF trap (VEGFR1/Fc, 2 μg/eye) at P17. At 24 hours posttreatment, mRNA for inflammatory marker was quantified by qPCR and normalized to OIR mice kept in room air, (n = 8 to 12 mice).

Discussion

Ischemic retinopathy is characterized by a period of retinal ischemia due to vessel regression or occlusion, followed by pathological retinal and vitreous NV. Extensive studies have been performed to address the mechanisms underlying NV with the aim of finding effective antiangiogenic therapies. Although a number of angiogenic molecules have been identified, VEGF is the only one whose blockade has been shown to effectively induce regression of established NV in retinopathy.36,37 While anti-VEGF therapy has been successfully applied in humans, issues such as efficacy, impairment of revascularization, and the long-term safety of VEGF antagonism have emerged as significant concerns.

We and others have previously demonstrated that sustained normobaric hyperoxia administered during the preproliferative phase of ischemic retinopathy either before the retina ischemia or after a period of retinal ischemia but prior to the development of vitreous NV not only prevents the development of vitreous NV, but paradoxically accelerates the process of retinal revascularization.17–19 In the present study, we investigated the effect of supplying oxygen during the proliferative phase of ischemic retinopathy. Here we provide the first evidence that HT causes rapid regression of established vitreous NV while sparing existing intraretinal vessels involved in revascularization. Unlike VEGF trap, which caused some retinal inflammation as noted by us and by others previously,38 HT actually suppressed inflammation similar to when HT was used in the preproliferative phase of ischemic retinopathy.19 Together with previous studies showing beneficial effects when oxygen is supplied during the preproliferative phase of ischemic retinopathy,17–19 the present study indicates a broad therapeutic time window for HT and warrants further investigation of the beneficial actions of HT in ischemic retinopathy. The noninvasive and nondestructive nature of HT makes it particularly appealing for clinical use. Unlike laser photocoagulation, HT does not require clear ocular media to administer, and its use in adults is not associated with any major side effects. Moreover, given the availability of affordable, portable hyperbaric oxygen chambers, hyperoxia therapy may be a feasible option for treatment of ischemic retinopathy with a home-based approach. However, although diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, and retinopathy of prematurity share similarities in pathogenesis in that the NV is driven by hypoxia,39,40 the conditions differ in their time course. Therefore, optimal conditions of HT delivery, including timing and oxygen concentration, need to be determined independently for different diseases.

Thus far, investigation of oxygen therapy in human ischemic retinopathy has been limited. Its use in human ROP is restricted by the clinical challenges of tightly controlling blood oxygenation in unstable neonates, as well as the potential for inducing oxygen-related pulmonary complications and causing brain damage in the premature infant.41–44 Moreover, the timing of HT for ROP is critical as early intervention may cause more severe ROP if delivered to immature vessels which are sensitive to hyperoxia-induced injury. Hyperoxia-induced vessel regression and aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity have even been observed in some premature infants born at 33 to 35 weeks gestational age when sight-threatening ROP should be no longer a risk.45 In spite of these limitations, oxygen therapy has been evaluated in a small case series of patients with chronic diabetic macular edema20 and was found to cause a significant and prolonged reduction in central macular thickness and to improve visual function. We are not aware of any trials evaluating oxygen therapy in cases of retinopathy with significant ischemia (preproliferative or proliferative). However, there have been case reports in which hyperbaric oxygen has been used for treatment of central retinal vein occlusion with good visual outcomes.21,22

Although our data demonstrate that a short course of HT can effectively cause involution and apoptosis of preretinal neovascular channels and this effect appears to be mediated by loss of activity though VEGFR2, it is not clear from these experiments alone that short-term administration of hyperoxia would be sufficient for the clinical treatment of ischemic retinopathies. The use of anti-VEGF agents is highly effective in regressing vitreous NV during ischemic retinopathies, but the duration of this effect is usually limited because the ischemia may persist, leading to recurrence of the NV.46–48 Since the avascular area still persists after short term HT, it is not clear whether NV would recur later and require repeated hyperoxia treatment. Evidence from our prior work, however, suggests that hyperoxia has different characteristics from anti-VEGF agents in that longer duration of HT suppresses pathological neovascularization while promoting physiologic revascularization of the ischemic retina when delivered from P14 to P20.19 Although hyperoxia induces regression of developing vessels and causes OIR, our previous study in the mouse showed that a relatively sharp transition occurs in the retina between P11 and P15, after which hyperoxia causes neither capillary vasoobliteration nor suppression of physiological revascularization.49 Continued exposure of the retina to hyperoxic conditions, past P17, actually ends up accelerating the rate of retinal revascularization compared with room air controls.19,49 The mechanism by which intraretinal capillaries acquire their tolerance to hyperoxia is not clear. It is possible that the mature vessel gains proper pericyte coating50 and interaction with glia, which impart capillary stabilization. The slight increase in avascular area following the short course of hyperoxia treatment on P17 is unexpected. Careful examination of the vascular changes indicated that this was due to loss of coverage by abnormal vessels after HT. Moreover, the increase in avascular area is quite small compared with the dramatic regression seen in preretinal pathological NV tufts. The difference in oxygen sensitivity between preretinal pathological NV tufts and mature intraretinal vessels suggests that hyperoxia provides a selective therapeutic effect when applied with proper timing. Further studies, taking into account optimal oxygen concentrations and durations of treatment, are necessary to address these complex issues involved in optimizing the treatment regimens needed to reverse pathological pre-retinal neovascularization while simultaneously facilitating physiologic revascularization and alleviating ischemia.

The precise mechanisms by which HT causes regression of NV tufts remain to be elucidated. Considering the pleiotropic effects of HT,19 it is possible that multiple pathways are involved. However, our data suggest that HT-induced loss of survival signaling through the VEGFR2/Flk-1/KDR receptor is a key mechanism leading to regression and apoptosis of pathological NV. Similar to supplying oxygen in preproliferative ischemic retinopathy,51 HT during proliferative ischemic retinopathy exerts a direct inhibitory effect on VEGF expression. Moreover, HT prominently reduces VEGFR2 in NV tufts. Compensating this pathway with both VEGF-A and VEGF-E (selective for VEGFR2)—but not PlGF-1 (selective for VEGFR1)—was able to prevent HT-induced apoptosis and regression. In contrast, blockade of VEGFR2 with a specific polypeptide inhibitor or VEGFR2-specific siRNA mimicked the effect of HT and induced apoptosis of pathological NV tufts while leaving existing vessels relatively intact. Although the relative contribution of changes in VEGFR2 and VEGF to endothelial apoptosis is not clear, as both may be involved to a significant degree, it is noteworthy that the inhibitor and siRNA selectively and directly targeted VEGFR2. VEGFR2 is the major mediator of VEGF signaling in endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis.34 Regulation of VEGFR2 at transcriptional or posttranslational levels has been identified as a key mechanism by which other signaling pathways intervene in the process of angiogenesis.52–54 In addition to anti-VEGF therapy, VEGFR2 blockers have been developed to treat other angiogenesis-related diseases such as tumor growth during cancer.55

Upregulation of VEGFR2 in NV tufts has been observed in ischemic retinopathy.56 In this study, we provide the first evidence that HT selectively reduces the high VEGFR2 level in NV tufts and causes VEGFR2 redistribution from pathological vessels to neural tissue. The specific mechanisms underlying this dramatic effect remain to be elucidated. Given that transcription factor HIF-2α is a critical regulator of VEGFR2 expression57 and NV tufts occur in hypoxic conditions, it is possible that VEGFR2 expression in NV tufts is induced by hypoxia-driven HIF-2α accumulation, whereas HT blocks such effect. However, hypoxia treatment does not increase but instead decreases VEGFR2 mRNA in cultured endothelial cells,58 indicating other factors released from hypoxic neural retina may be critical. Signals from these factors may work alone or together with HIF-2α to increase VEGFR2 expression in NV during hypoxia. Cytokines such as VEGF, IL-6, TNF-α, and FGF2 are upregulated in the hypoxic retina and have been shown to induce VEGFR2 expression in endothelial cells under different conditions.19,52,59,60 In addition to regulation at the mRNA level, VEGFR2 expression can be regulated posttranslationally54 and hyperoxia may accelerate such processes. Interestingly, while VEGFR2 associated with the NV tufts is rapidly diminished by HT, VEGFR2 in neural retina is prominently increased. This implies different regulatory mechanisms and suggests that VEGFR2 may serve to sequester VEGF locally. Insight into mechanisms by which HT differentially regulates VEGFR2 expression in NV tufts versus neural retina may open new perspectives for developing therapeutic approaches in addition to HT to treat NV while sparing VEGFR2-mediated beneficial effects such as neuronal protection.

Hyperoxia also induces capillary apoptosis and regression during developmental angiogenesis and therefore causes retinopathy of prematurity.33 Similar to hyperoxia-induced NV regression, repression of the VEGF-mediated vascular survival signal by hyperoxia has a key role in this process.33 However, hyperoxia-induced regression of the developing capillaries is prevented by PlGF-1, a selective VEGFR1 agonist, but not by VEGF-E, a selective VEGFR2 agonist.61 In contrast, hyperoxia-induced NV regression is prevented by VEGF-E but not by PlGF-1. Therefore, there is a fundamental difference between these two processes in that VEGFR1 is critical in maintaining the vasculature of the neonatal retina and VEGFR2 is critical in maintaining NV tufts. Taken together with our previous finding that HT also promotes vascular recovery when administrated during ischemic preproliferative phase in the OIR model,19 our data suggest that there are key physiological differences among developmental angiogenesis, pathological angiogenesis, and reparative angiogenesis. These differences deserve further investigation, as they may provide avenues for selectively preventing regression in retinal development, targeting pathological NV, and sparing or promoting retinal revascularization.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Georgia Health Sciences University Vision Discovery Institute (SEB and RBC); by NIH Grants EY11766 (RBC, RWC), EY04618 and VA Merit Award (RBC); by NIH Grant HL70215 (RWC); by NIH Grant EY022694, American Heart Association 11SDG4960005, and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation JDRF 10-2009-575 (WZ); and by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Disclosure: H. Liu, None; W. Zhang, None; Z. Xu, None; R.W. Caldwell, None; R.B. Caldwell, None; S.E. Brooks, None

References

- 1. Fong DS, Girach A, Boney A. Visual side effects of successful scatter laser photocoagulation surgery for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a literature review. Retina. 2007; 27: 816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tolentino MJ. Current molecular understanding and future treatment strategies for pathologic ocular neovascularization. Curr Mol Med. 2009; 9: 973–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kurihara T, Westenskow PD, Bravo S, Aguilar E, Friedlander M. Targeted deletion of Vegfa in adult mice induces vision loss. J Clin Invest. 2012; 122: 4213–4217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishijima K, Ng YS, Zhong L, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A is a survival factor for retinal neurons and a critical neuroprotectant during the adaptive response to ischemic injury. Am J Pathol. 2007; 171: 53–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saint-Geniez M, Maharaj AS, Walshe TE, et al. Endogenous VEGF is required for visual function: evidence for a survival role on muller cells and photoreceptors. PLoS One. 2008; 3: e3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ness T, Feltgen N, Agostini H, Bohringer D, Lubrich B. Toxic vitreitis outbreak after intravitreal injection. Retina. 2010; 30: 332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pilli S, Kotsolis A, Spaide RF, et al. Endophthalmitis associated with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy injections in an office setting. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 145: 879–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Q, Chang Q, Cox RA, Gong X, Gould LJ. Hyperbaric oxygen attenuates apoptosis and decreases inflammation in an ischemic wound model. J Invest Dermatol. 2008; 128: 2102–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knighton DR, Silver IA, Hunt TK. Regulation of wound-healing angiogenesis-effect of oxygen gradients and inspired oxygen concentration. Surgery. 1981; 90: 262–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abidia A, Laden G, Kuhan G, et al. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in ischaemic diabetic lower extremity ulcers: a double-blind randomised-controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003; 25: 513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Faglia E, Favales F, Aldeghi A, et al. Adjunctive systemic hyperbaric oxygen therapy in treatment of severe prevalently ischemic diabetic foot ulcer. A randomized study. Diabetes Care. 1996; 19: 1338–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chong KT, Hampson NB, Corman JM. Early hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves outcome for radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Urology. 2005; 65: 649–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Monies-Chass I, Hashmonai M, Hoere D, Kaufman T, Steiner E, Schramek A. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment as an adjuvant to reconstructive vascular surgery in trauma. Injury. 1977; 8: 274–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feldmeier JJ, Hampson NB. A systematic review of the literature reporting the application of hyperbaric oxygen prevention and treatment of delayed radiation injuries: an evidence based approach. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2002; 29: 4–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Birol G, Budzynski E, Wangsa-Wirawan ND, Linsenmeier RA. Hyperoxia promotes electroretinogram recovery after retinal artery occlusion in cats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 3690–3696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang YH, Chen PL, Tai MC, Chen CH, Lu DW, Chen JT. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates the blood-retinal barrier breakdown in diabetic retinopathy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006; 34: 584–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Phelps DL. Reduced severity of oxygen-induced retinopathy in kittens recovered in 28% oxygen. Pediatr Res. 1988; 24: 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan-Ling T, Gock B, Stone J. Supplemental oxygen therapy. Basis for noninvasive treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995; 36: 1215–1230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang W, Yokota H, Xu Z, et al. Hyperoxia therapy of pre-proliferative ischemic retinopathy in a mouse model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 6384–6395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nguyen QD, Shah SM, Van Anden E, Sung JU, Vitale S, Campochiaro PA. Supplemental oxygen improves diabetic macular edema: a pilot study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roy M, Bartow W, Ambrus J, Fauci A, Collier B, Titus J. Retinal leakage in retinal vein occlusion: reduction after hyperbaric oxygen. Ophthalmologica. 1989; 198: 78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wright JK, Franklin B, Zant E. Clinical case report: treatment of a central retinal vein occlusion with hyperbaric oxygen. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2007; 34: 315–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, et al. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994; 35: 101–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, et al. Computer-aided quantification of retinal neovascularization. Angiogenesis. 2009; 12: 297–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gustavsson C, Agardh CD, Zetterqvist AV, Nilsson J, Agardh E, Gomez MF. Vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression in mice retinal vessels is affected by both hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. PLoS One. 2010; 5: e12699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Podesta F, Romeo G, Liu WH, et al. Bax is increased in the retina of diabetic subjects and is associated with pericyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2000; 156: 1025–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connor KM, SanGiovanni JP, Lofqvist C, et al. Increased dietary intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2007; 13: 868–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gardiner TA, Gibson DS, de Gooyer TE, de la Cruz VF, McDonald DM, Stitt AW. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha improves physiological angiogenesis and reduces pathological neovascularization in ischemic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2005; 166: 637–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishida S, Usui T, Yamashiro K, et al. VEGF164-mediated inflammation is required for pathological, but not physiological, ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. J Exp Med. 2003; 198: 483–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ljubimov AV, Caballero S, Aoki AM, Pinna LA, Grant MB, Castellon R. Involvement of protein kinase CK2 in angiogenesis and retinal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 4583–4591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ritter MR, Banin E, Moreno SK, Aguilar E, Dorrell MI, Friedlander M. Myeloid progenitors differentiate into microglia and promote vascular repair in a model of ischemic retinopathy. J Clin Invest. 2006; 116: 3266–3276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998; 281: 1312–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alon T, Hemo I, Itin A, Pe'er J, Stone J, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nat Med. 1995; 1: 1024–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shibuya M, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by VEGF receptors in regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006; 312: 549–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Binetruy-Tournaire R, Demangel C, Malavaud B, et al. Identification of a peptide blocking vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis. Embo J. 2000; 19: 1525–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adamis AP, Altaweel M, Bressler NM, et al. Changes in retinal neovascularization after pegaptanib (Macugen) therapy in diabetic individuals. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113: 23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stergiou PK, Symeonidis C, Dimitrakos SA. Descending doses of intravitreal bevacizumab for the regression of diabetic neovascularization. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011; 89: 218–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Olsen TW, Feng X, Wabner K, Csaky K, Pambuccian S, Cameron JD. Pharmacokinetics of pars plana intravitreal injections versus microcannula suprachoroidal injections of bevacizumab in a porcine model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 4749–4756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arden GB, Sidman RL, Arap W, Schlingemann RO. Spare the rod and spoil the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005; 89: 764–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Buehl W, Sacu S, Schmidt-Erfurth U. Retinal vein occlusions. Dev Ophthalmol. 46: 54–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Supplemental Therapeutic Oxygen for Prethreshold Retinopathy Of Prematurity (STOP-ROP), a randomized, controlled trial I: primary outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000; 105: 295–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McGregor ML, Bremer DL, Cole C, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity outcome in infants with prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity and oxygen saturation >94% in room air: the high oxygen percentage in retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics. 2002; 110: 540–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lloyd J, Askie L, Smith J, Tarnow-Mordi W. Supplemental oxygen for the treatment of prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; CD003482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sifringer M, Bendix I, Borner C, et al. Prevention of neonatal oxygen-induced brain damage by reduction of intrinsic apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2012; 3: e250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shah PK, Narendran V, Kalpana N. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity in large preterm babies in South India. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012; 97: F371–F375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hu J, Blair MP, Shapiro MJ, Lichtenstein SJ, Galasso JM, Kapur R. Reactivation of retinopathy of prematurity after bevacizumab injection. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130: 1000–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patel RD, Blair MP, Shapiro MJ, Lichtenstein SJ. Significant treatment failure with intravitreous bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130: 801–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hoang QV, Kiernan DF, Chau FY, Shapiro MJ, Blair MP. Fluorescein angiography of recurrent retinopathy of prematurity after initial intravitreous bevacizumab treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 128: 1080–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gu X, Samuel S, El-Shabrawey M, et al. Effects of sustained hyperoxia on revascularization in experimental retinopathy of prematurity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002; 43: 496–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Benjamin LE, Hemo I, Keshet E. A plasticity window for blood vessel remodelling is defined by pericyte coverage of the preformed endothelial network and is regulated by PDGF-B and VEGF. Development. 1998; 125: 1591–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pierce EA, Foley ED, Smith LE. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by oxygen in a model of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996; 114: 1219–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Giraudo E, Primo L, Audero E, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and of its co-receptor neuropilin-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998; 273: 22128–22135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meissner M, Reichenbach G, Stein M, Hrgovic I, Kaufmann R, Gille J. Down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 is a major molecular determinant of proteasome inhibitor-mediated antiangiogenic action in endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2009; 69: 1976–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shaik S, Nucera C, Inuzuka H, et al. SCFbeta-TRCP suppresses angiogenesis and thyroid cancer cell migration by promoting ubiquitination and destruction of VEGF receptor 2. J Exp Med. 2012; 209: 1289–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shen G, Li Y, Du T, et al. SKLB1002, a novel inhibitor of VEGF receptor 2 signaling, induces vascular normalization to improve systemically administered chemotherapy efficacy. Neoplasma. 2012; 59: 486–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Suzuma K, Takagi H, Otani A, Suzuma I, Honda Y. Increased expression of KDR/Flk-1 (VEGFR-2) in murine model of ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. Microvasc Res. 1998; 56: 183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elvert G, Kappel A, Heidenreich R, et al. Cooperative interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha (HIF-2alpha) and Ets-1 in the transcriptional activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (Flk-1). J Biol Chem. 2003; 278: 7520–7530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Hein TW, Olszewska P, Carney DH. Chronic hypoxia attenuates VEGF signaling and angiogenic responses by downregulation of KDR in human endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009; 296: C1162–C1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Murakami M, Nguyen LT, Hatanaka K, et al. FGF-dependent regulation of VEGF receptor 2 expression in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011; 121: 2668–2678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shen BQ, Lee DY, Gerber HP, Keyt BA, Ferrara N, Zioncheck TF. Homologous up-regulation of KDR/Flk-1 receptor expression by vascular endothelial growth factor in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1998; 273: 29979–29985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shih SC, Ju M, Liu N, Smith LE. Selective stimulation of VEGFR-1 prevents oxygen-induced retinal vascular degeneration in retinopathy of prematurity. J Clin Invest. 2003; 112: 50–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.