Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus transmitted by Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in tropical areas of Africa, Asia, and the islands of the Indian Ocean. In 2007 and 2009, CHIKV was transmitted outside these tropical areas and caused geographically localized infections in people in Italy and France. To temporally and spatially characterize CHIKV infection of Ae. albopictus midguts, a comparison of viral distribution in mosquitoes infected per os or by enema was conducted. Ae. albopictus infected with CHIKV LR 5′ green fluorescent protein (GFP) at a titer 106.95 tissue culture infective dose50 (TCID50)/mL, were collected and analyzed for virus dissemination by visualizing GFP expression and titration up to 14 days post inoculation (dpi). Additionally, midguts were dissected from the mosquitoes and imaged by fluorescence microscopy for comparison of midgut infection patterns between orally- and enema-infected mosquitoes. When virus was delivered via enema, the anterior midgut appeared more readily infected by 3 dpi, with increased GFP presentation observed in this same location of the midgut at 7 and 14 dpi when compared to orally-infected mosquitoes. This work demonstrates that enema delivery of virus is a viable technique for use of mosquito infection. Enema injection of mosquitoes may be an alternative to intrathoracic inoculation because the enema delivery more closely models natural infection and neither compromises midgut integrity nor involves a wound that can induce immune responses. Furthermore, unlike intrathoracic delivery, the enema does not bypass midgut barriers to infect tissues artificially in the hemocoel of the mosquito.

Key Words: Chikungunya virus, Aedes albopictus, Aedes aegypti, Enema injection

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an arthropod-borne virus of the genus Alphavirus and family Togaviridae. The first isolates of CHIKV were identified in 1952 on the Makonde Plateau in the Southern Province of Tanganyika in what is now the east African state of Tanzania (Robinson 1955). Clinical distinction of chikungunya fever symptoms from dengue fever is the severity of joint pain/arthritis experienced during CHIKV infection, with instances of persistent arthritis lasting months to years in some patients (Robinson 1955, Tesh 1982). CHIKV has maintained an endemic presence in central and south Africa and in southeast Asia from the 1960s to the present (Powers and Logue 2007). CHIKV typically was associated with Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in the urban setting and exists in a human-to-mosquito transmission cycle, with no other amplifying host needed. Recently, an increase in chikungunya fever epidemics has been documented, and a single point mutation in the viral genome has been identified that increases the capacity of the virus to infect Aedes albopictus mosquitoes (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006). Of greater consequence are the incidence of transmission and subsequent distribution of CHIKV to nonendemic regions by travelers to epidemic regions or individuals who live in epidemic areas. One of the first, and most notable, range expansions took place in 2007 when an individual from India developed chikungunya fever while visiting Italy and most probably infected local mosquitoes, resulting in an outbreak that eventually infected 205 individuals in Italy (Rezza et al. 2007, Seyler et al. 2008). Spread to nonendemic regions also occurred in France, with 2 infected individuals causing great concern that globally distributed Aedes mosquitoes may successfully vector CHIKV to new regions (Gould et al. 2010).

The basic model for mosquito infection by CHIKV in nature, and in the laboratory setting, follows a per os infection model where the vector imbibes an infectious blood meal, filling the midgut from posterior to anterior (Clements 1992, Guptavanij and Venard 1965), followed by infection of midgut epithelial cells by virus in the blood meal and dissemination of virus throughout tissues of the mosquito until the salivary glands become infected and the vector is capable of transmission (Romoser et al. 2004). This is the accepted model for viral infection of the mosquito and subsequent transmission to its next host; however, the specific mechanisms and key aspects of how individual virus particles overcome hypothetical innate infection barriers to infect and disseminate in the mosquito remains to be elucidated (Hardy 1988). Specifically, it is unknown whether or not a specific population or subpopulation of mesenteronal epithelial cells is more susceptible to early infection of CHIKV by means of increased virus-specific receptors and/or by anatomical orientation and subsequent proximal exposure to the infectious blood meal as it enters the lumen of the midgut. Understanding these infection processes and correlating the preferential location of infection in the mosquito midgut will increase our understanding of viral dissemination rates to the salivary glands. Additionally, determining the proximity of midgut infection with reference to the salivary glands may further explain the varied rates of virus transmission observed in mosquitoes.

As discussed by Higgs (2004a), some published observations have reported that infections of the mosquito midgut following the natural per os infection route are initiated in the posterior midgut (Doi et al. 1967, Doi 1970, Kuberski 1979) and then progress anteriorly prior to dissemination. It is unclear if this reported pattern is due to the presence of a subpopulation of susceptible cells in the posterior midgut or if it is due to some aspect (physical/physiological) of the blood entering the midgut. Given that over time the infections that are initiated in just a few cells (Weaver et al. 1988, Girard et al. 2004, Smith et al. 2008) can be seen to spread throughout the midgut, it is clear that most cells can be infected. However, it is unclear why even with high-titer blood meals so few cells are initially infected. One possible explanation is that cell susceptibility to infection may increase over time, perhaps as a result of blood meal digestion, which is associated with many physiological and hormonal changes in the mosquito, such as ovarian development. However, because the enema–inoculum did not contain blood, this question was not answered in this study.

This paper focuses on the infection processes associated with the initial route of virus infection of the midgut. Delivery of the virus by enema mimics some aspects of blood feeding, including midgut distention, but provides an opportunity to examine the effect of viral distribution because delivery is via the hindgut rather than the foregut. Because the rectal injection of material into the midgut is in the opposite direction of imbued blood meals that have been demonstrated to fill the midgut from posterior to anterior by Guptavanij and Venard (1965), we believe this model affords the observation of a similar mode of midgut fill, but in reverse order, filling the anterior midgut first followed by the posterior midgut. This alternate direction of alphavirus-infected medium movement into the midgut should ultimately have no impact on the observed infection pattern in mosquito midguts if the current hypothesis of a preferentially susceptible population of midgut cells exists in the posterior midgut (Weaver et al. 1988, Smith et al. 2008). However, if an alternative pattern of early viral CHIKV infection is observed, with infected cells being clustered in foci forward of the posterior midgut, this might reflect either a lack of specific CHIKV susceptible cells in the posterior midgut, or be an artifact related to the rectal delivery route. Therefore, we explored the question of whether or not enema delivery of fluorescent protein–expressing virus results in a similar or different distribution of infected cells compared to per os–infected mosquitoes.

The rectal administration of blood by enema, although seldom used, has been successfully used to circumvent the mosquito innate physiological barriers and/or host-seeking behaviors, thereby providing a unique opportunity to observe vector response to toxins or parasites (Briegel 1975, Briegel and Lea 1975). Previous applications of this technique were less successful at examining viral infection of arbovirus vectors (both ticks and mosquitoes) as opposed to the standard per os infection or the more invasive technique of intrathoracic (IT) injection that typically fails to infect luminal epithelial cells of the midgut (Putnam and Scott 1995, Turell et al. 1997). However, we have successfully delivered CHIKV to Ae. albopictus La Réunion (LR) strain mosquitoes in a manner that closely resembles the natural patterns of mosquito infection while also providing commensurate levels of virus titer. With the use of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing CHIKV infectious clone (originally derived from the RNA of CHIKV LR2006 OPY1 strain maintained by the World Reference Center for Arboviruses at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX), infected cells in the midgut of the mosquitoes were readily identified soon after infection in both orally-infected and enema-infected mosquitoes. In these experiments, there was no overt detriment to survivability observed in the mosquitoes upon rectal enema administration.

Materials and Methods

CHIKV LR 5′ GFP enema and blood meal

A full-length, double subgenomic CHIKV LR strain infectious clone with a GFP gene inserted 5′ to the structural genes (CHIKV LR 5′ GFP) was created and previously described (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006). The infectious clone was linearized with NotI and in vitro transcribed using an mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). It was then electroporated into BHK-21 cells and seeded into a 75-cm2 flask with minimum essential medium-α (MEMα) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine, and 1% MEM vitamins (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C with 5% CO2 as previously described (Higgs et al. 1997). Two days postelectroporation, infectious medium was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until used for experiments. Virus stock was titrated at 106.95 tissue culture infectious dose50 (TCID50)/mL.

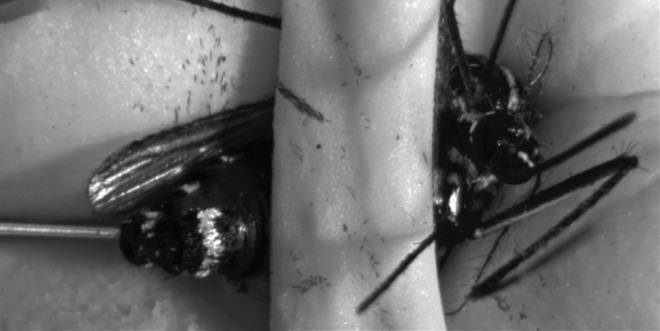

Aedes albopictus LR mosquitoes were reared in an Arthropod Containment Level 2 insectary at 27°C with a relative humidity of 80% with a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod as previously described (Higgs 2004b, 2004c). At 7–10 days posteclosion, separate groups of female mosquitoes were infected with CHIKV LR 5′ GFP either by infectious blood meal or by enema administration. Infectious blood meals consisting of a 1:1 mixture of virus stock and defibrinated sheep blood (DSB) (Colorado Serum Company, Boulder, CO) was fed to female mosquitoes for 1 h using a Hemotek feeding system (Discovery Workshops, Accrington, United Kingdom) covered by mouse skins and warmed to 37°C. After feeding, engorged females were sorted and maintained with 10% sucrose ad libitum in an environmental chamber at the previously described conditions. For enema administration, a 1:1 mixture of virus stock and MEMα (as previously described) was injected at volumes of 2–3 μL under a stereomicroscope to confirm the delivery of inoculum was into the midgut. Calibrated Microcaps® (100 μL) (Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA) were pulled to needle tips in a PC-10 Puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) at a temperature of 73.6°C. Cold anesthetized mosquitoes were secured in grooved platforms constructed from malleable craft putty and secured by a small transverse band of putty for administration (Fig. 1). Final titers for both the enema solution and infectious blood meal were comparable at 106.95 TCID50/mL and 106.52 TCID50/mL, respectively. Uninfected mosquitoes that were fed only DSB or administered enemas consisting of MEMα only were used as controls to monitor if manipulation had deleterious effects, for example, increased mortality rates compared with unmanipulated mosquitoes. Both per os– and enema-initiated infections were performed in duplicate using the same virus stock with equivalent titers of enema solution and blood meal administered both times as confirmed by TCID50 assay. All infectious virus work was carried out in an Arthropod Containment Level 3 insectary.

FIG. 1.

Ae. albopictus mosquito receiving an enema inoculation. The mosquito was cold anesthetized prior to being restrained in a concave modeler's clay platform and secured by a separate, smaller band of modeler's clay.

Ex vivo fluorescence microscopy of midguts

Cohorts from orally-infected/uninfected and enema-infected/uninfected mosquito treatment groups were collected at 3, 7, and 14 days postinfection (dpi) for fluorescence imaging of dissected midguts. At each time point, mosquitoes were placed at −20°C up to 90 sec before transfer to a solution of 70% ethanol for 30 sec for surface decontamination. Mosquitoes were then transferred to Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA). Midguts were dissected from the abdomen by making a small incision in the anterior ventral abdomen, then displacing the abdomen from the thorax by pulling on the posterior abdomen. Separation in this manner offered complete extraction of the midgut, including the Malpighian tubules, allowing for orientation of the posterior and anterior midgut. Upon dissection, midguts were immediately transferred to 12-well plates covered in aluminum foil containing chilled BD Cytofix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and then placed at 4°C for 24 h. Midguts were immersed in SlowFade® Gold Antifade reagent (Invitrogen) on microscope slides, coverslips were applied, and slides were placed in a slide box until imaging. Care was taken to keep mounted midguts in the dark. Digital epifluorescent images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse Ti Perfect Focus system inverted microscope with NIS-Elements software.

Mosquito titrations

Leibovitz L-15 medium was used for titrations and was supplemented with 10% tryptose phosphate broth, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine, 1% MEM, vitamins, and 250 μg/mL amphotericin B (Invitrogen). Aedes albopictus LR were collected at 0, 3, 7, and 14 dpi and immediately placed at −80°C until titration. Upon thawing, individual mosquitoes were homogenized in microcentrifuge tubes containing a 4.5-mm steel ball bearing and L-15 medium with a TissueLyser II platform (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for 4 min at 26 Hz. Ten-fold serial dilutions were prepared from whole-body homogenates and titrated on Vero cell culture with L-15 medium and incubated at 37°C with no CO2 as described previously (Higgs et al. 1997, McGee et al. 2009). Titrations were also performed on blood meals and enema inocula collected immediately postinfection. End point titers were determined at 7 dpi based on GFP detection and cytopathic effect using an Olympus IX-70 epifluorescence microscope. Differences in whole-body titration between fed and enema manipulated mosquitoes were analyzed using an unpaired t-test in Graphpad Prism v5.

Results

Comparative infection rates of per os–exposed and enema-administered CHIKV in Ae. albopictus

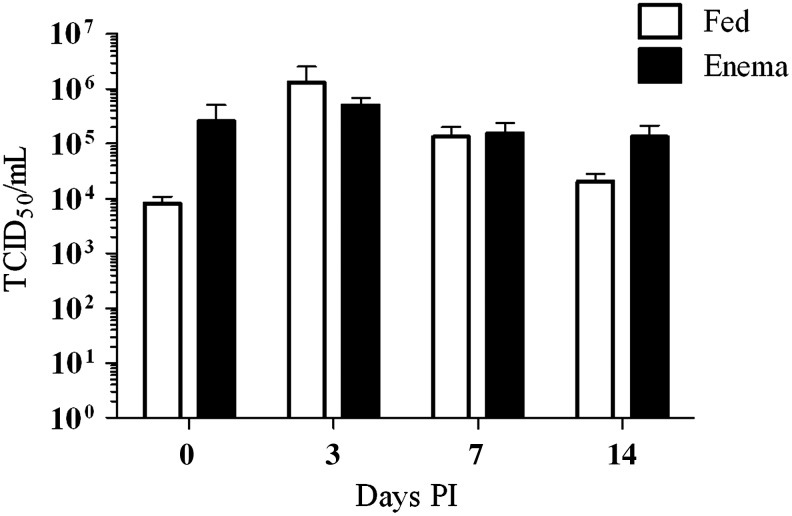

One question addressed by this research was the effect of enema administration on infection rates of CHIKV in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes and whether or not those rates were comparable to a per os–infected mosquito. Infection rates between per os– and enema-infected mosquitoes were determined by titration of mosquitoes collected at 0, 3, 7, and 14 dpi. Infected and uninfected mosquitoes were collected at the same time points for statistical analysis excluding those mosquitoes that fell below the limit of detection (101.06 TCID50/mL) (Table 1). Compared to negative control nonmanipulated cohorts, the orally-infected and enema-infected mosquitoes displayed no increased morbidity for the duration of these experiments (data not shown). The average infectious titers for CHIKV enema-infected mosquitoes collected 0, 3, 7, and 14 dpi were 105.41, 105.70, 105.19, and 105.12 TCID50/mL, respectively. The corresponding titers for CHIKV-fed mosquitoes were 103.90, 106.10, 105.12, and 104.31 Log10 TCID50/mL, respectively. For the time periods sampled, there were no statistical differences (p<0.05) in the infection rates and viral titers of the enema administered and per os–fed mosquitoes using an unpaired Student t-test (Table 1 and Fig. 2). In a manner previously described for this infectious clone by Tsetsarkin et al. (2006), both fed and enema-infected mosquitoes experienced an elevation in CHIKV titer at 3 dpi, indicative of viral replication (Fig. 3). Subsequent mosquito titer levels slightly decreased after 3 dpi, as previously reported (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006). Although mosquitoes administered CHIKV infectious enemas displayed a slower decline in viral titer at 14 dpi when compared to mosquitoes infected by CHIKV blood meal, this was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Infection Rates and Average Titer of Aedes albopictus (LR) Mosquitoes Infected per os and by Enema with CHIKV-LRic

| Infection | Day p.i. | Infection Rate Infected/total (%) | Average titer (TCID50/mL) | ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per os CHIKVa | 0 | 15/15 (100) | 103.90 | 4.04 |

| 3 | 16/16 (100) | 106.10 | 6.67 | |

| 7 | 14/15 (93) | 105.12 | 5.39 | |

| 14 | 15/15 (100) | 104.31 | 4.48 | |

| Enemab | 0 | 13/17 (76) | 105.41 | 5.41 |

| 3 | 14/15 (93) | 105.70 | 5.23 | |

| 7 | 11/13 (85) | 105.19 | 4.90 | |

| 14 | 11/11 (100) | 105.12 | 4.91 |

Titer of CHIKV-LR blood meal fed to Ae. albopictus: 106.52 TCID50/mL.

Titer of CHIKV-LR enema administered to Ae. albopictus: 106.95 TCID50/mL.

LR, La Réunion; CHIKV, chikungunya virus; p.i., postinfection; TCID50, tissue culture infectious dose50; SD, standard deviation.

FIG. 2.

Whole body titrations of Ae. albopictus (LR) mosquitoes post-infection with CHIKV-LR GFP infectious clone.

FIG. 3.

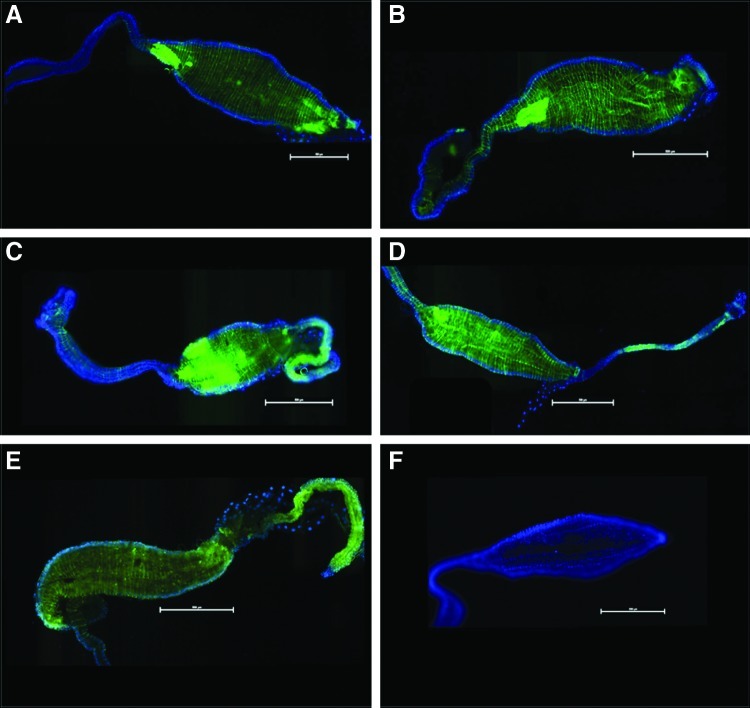

Epifluorescent images of female Ae. albopictus mosquito midguts infected with CHIKV-LR-5'-GFP. Blue fluorescence is DAPI stain. Midguts in panels A and B are negative controls having only been fed with DSB or inoculated with an MEMα enema respectively. Panels C, E and G were dissected from mosquitoes that were fed blood meals with CHIKV LR 5' GFP at a titer of 6.52 log10 TCID50/mL at 3, 7, and 14 dpi. Panels D, F and H were dissected from mosquitoes that were injected with enemas with CHIKV LR 5' GFP at a titer of 6.95 log10 TCID50/mL at 3, 7, and 14 dpi. Midguts are oriented with the anterior to the left of each image. (Scale=500μM).

Ex vivo imaging of Ae. albopictus LR midguts infected with CHIKV

To determine if enema administration alters the course of infection within the midgut of the mosquito compared with per os infections, fluorescent imaging of dissected midguts was performed. The use of GFP-expressing infectious clones has greatly enhanced the capability to visualize the infection processes of CHIKV as it spreads through the midgut of the mosquito into the hemocoel and then the salivary glands of the mosquito during the extrinsic incubation period (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006). Although a greater amount of infection was observed in the orally-infected mosquitoes based upon the amount of GFP expression present in the midguts of these mosquitoes, differences in the dispersion and loci of infection in the midgut between the two infection techniques were observed. At 3 dpi and 7 dpi, it was observed that enema-infected mosquitoes demonstrated a greater dispersion of GFP-expressing CHIKV across the entirety of the midgut from the posterior midgut to the intussuscepted gut as opposed to the more isolated foci of per os–infected mosquitoes where the posterior midgut did not appear to become infected (Fig. 3). This can perhaps be attributed to the opposing direction of infectious material and the exerted force on the luminal side of the midgut during enema infection. Additionally, the rate of fill of the midgut is quite different between imbuement and enema inoculation and there were no blood cells in the enema inoculum to potentially obscure virus–epithelial cell interaction.

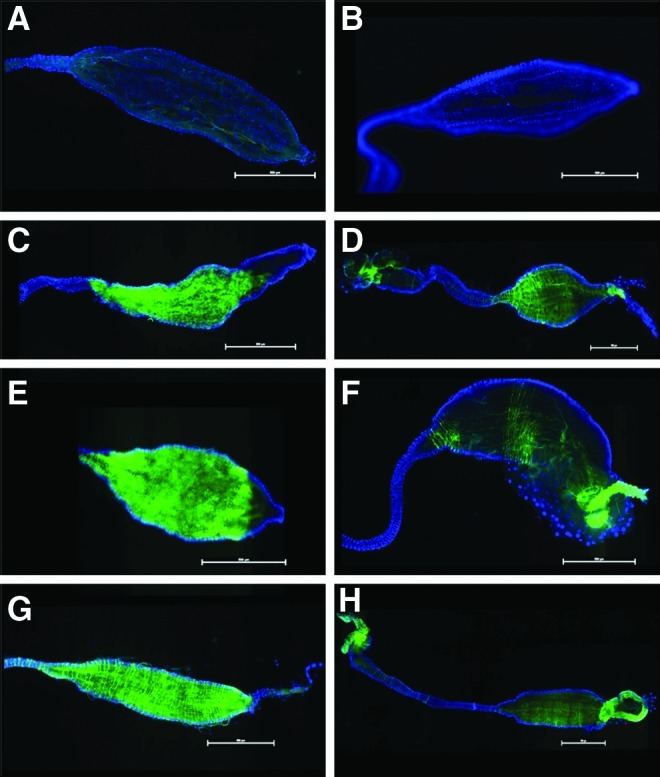

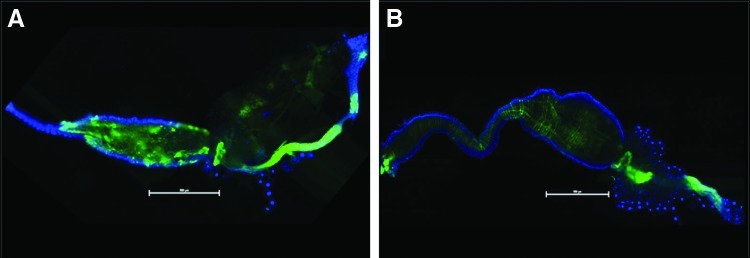

These factors may influence overall dispersion of CHIKV in the midgut, but should have no significant bearing on discerning whether or not a posterior population of midgut cells is preferentially susceptible to CHIKV infection. Furthermore, at 14 dpi, the dispersion pattern became less distinguishable between the two infection techniques (Fig. 3G, H), suggesting that while the enema process introduced a greater initial dispersion of CHIKV particles to the midgut, CHIKV-fed mosquitoes were just as likely to present with similar dispersion patterns as the infection process progressed. Interestingly, 14 dpi enema-infected mosquitoes had foci of GFP expression with greater intensity as compared to per os–infected mosquitoes in mesenteronal epithelial cells located in the anterior portion of the midgut (Fig. 4A–D).

FIG. 4.

Epifluorescent images of CHIKV-LR-5'-GFP enema injected midguts at 7 dpi (A and B) and 14 dpi (C and D). Panel E was dissected from a CHIKV-LR-5'-GFP fed mosquito at 14 dpi for comparison. The day seven and day 14 midguts reveal concentrated foci of GFP expression in the anterior midgut indicating a concentration of CHIKV infection. Similar observations can be seen, to a lesser extent, in the anterior midguts of infectious fed mosquitoes (E). Panel F is MEMα enema inoculated mosquito. Blue fluorescence is DAPI stain. (Scale=500μM).

Although similar areas were also observed in anterior midguts of CHIKV-fed mosquitoes 14 dpi, the observed presence of these foci was less substantial in GFP expression (Fig. 4E). With the inherent differences associated with the mechanical administration of CHIKV enemas, it is possible that the opposing movement of virus particles through the midgut lumen might induce elevated deposits of virus particles in subpopulations of epithelial cells. In both CHIKV-fed and enema-infected mosquitoes, there was GFP-expressing CHIKV in the anterior midgut with a diminished amount of CHIKV-GFP progressing up to the foregut/midgut junction. While this was true for both enema and fed methods, CHIKV-GFP expression was more clearly pronounced in the enema-infected mosquitoes. These data clearly indicate that initial CHIKV infection of the distended midgut, whether per os or by enema injection, is not restricted to cells of the posterior midgut of the A. albopictus mosquito and that the cells of the anterior midgut are equally susceptible, confirming observations previously suggested by Tsetsarkin et al. (2006). Additionally, these observations suggest that the physical impact of the imbibed infectious blood meal to the posterior midgut does not appear to promote increased infection of the posterior midgut because significant increase of GFP expression in the epithelial cells of this area were not observed (Fig. 3C, E, G).

Imaging of enema-infected midguts demonstrated accurate delivery of virus injections through the anus of the mosquito with clear progression of infection proceeding along the hindgut and into the midgut at 7 dpi (Fig. 5B). Infection of the lower digestive tract of the CHIKV-fed mosquitoes presented with similar patterns, but again, this was not observed until later in the course of the per os nfection technique at 14 dpi (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Epifluorescent images of CHIKV-LR-5'-GFP fed (A) and enema injected (B) mosquitoes at 14 and 7 dpi, respectively. GFP dissemination into the rectum/anus of the midguts dissected from orally infected mosquitoes was not observed at time points prior to 14 dpi. Midguts dissected from enema injected mosquitoes exhibited trace amounts of GFP expression as early as 3 dpi with confluent distribution throughout the lower digestive tract by 7 dpi. Blue fluorescence is DAPI stain. (Scale=500μM).

Discussion

The delivery of viruses by IT inoculation into mosquitoes is a commonly used technique but bypasses the midgut infection processes, potentially demonstrating viral dissemination that would otherwise not occur. Although this technique produces infected mosquitoes, one must be cautious when extrapolating between infections produced by IT and natural per os infections (Higgs et al. 1993). Enema delivery of viruses to their vectors has been reported (Putnam and Scott 1995, Turell et al. 1997), but is technically challenging and labor intensive. As with IT inoculation, it does not fully mimic per os infection; however, as used for this comparative study, the technique offers the ability to investigate some aspects of per os infection, because midgut cells are targeted. Putnam and Scott (1995) and Turell et al. (1997) reported that infections developed following the administration of agents by enema were significantly different when compared to vectors that were infected by blood meal. Both studies found average virus titers in enema-infected vectors were significantly higher when compared to per os–infected groups. Additionally, they found infection rates in the enema-infected groups to be elevated when compared to per os–infected vectors or more comparable to those receiving IT injection.

These observations suggested that enemas offered a poor method for analyzing viruses in their vectors; however, contrary to their conclusions, our results demonstrate that the technique has merit. Although Turell et al. (1997) used pressurized air for the delivery of their enema inoculums, our study used a syringe to apply moderate pressure for inoculum administration to avoid damaging the soft tissues of the mosquito's posterior alimentary canal. Our average mosquito titers between CHIKV-fed and enema-injected at specific time points was not significantly different (Table 1). Furthermore, while this technique has been examined in a limited capacity for arbovirus/vector interaction, numerous other enema applications have been successfully employed for physiology, toxicology, and parasitology studies (Klowden 1981, Klowden et al. 1983, Romoser et al. 1987, Higgs et al. 1993, Takken et al. 1998). These studies, as well as our own, demonstrate that delivery of agents/compounds directly to the mosquito midgut provides a practical, and perhaps more realistic, alternative to IT injection.

Using enemas allows delivery of precise viral inocula directly to the midgut epithelial cells. Further enhancements of the technique, for example by using blood as the delivery medium, would provide the opportunity to demonstrate natural mosquito physiological responses including formation of the peritrophic matrix (PM) and induction of oogenesis, responses not stimulated by IT injection. Stimulation of PM is significant in that the presence of a PM may influence the mosquito's susceptibility to infection by some parasites, although it does not influence viral infection (Kato et al. 2008). IT inoculation also may induce immune responses in arthropods because it involves cuticle penetration and these responses may influence infection dynamics. Administration of the enemas in these studies was optimized to deliver passive injections at a low enough pressure and volume (2–4 μL) to minimize overdistension of the midgut or induce sheering damage. These volumes were within the ranges utilized by Briegel and Lea (1975) and did not rupture the midgut due to overexpansion. Passive injection of virus simply means that inoculating needles were only placed at the tip of the mosquito anus with minimal insertion to avoid physical damage. This technique demonstrated progressive dispersion of virus (by GFP expression) along the lower digestive tract.

Although Putnam and Scott (1995) included red blood cells in their inoculums, this inoculum was not used in these studies. The composition of the enema solution can influence the actual administration of mosquito enemas both during injection and afterward. Although previously published reports on enemas used medium with blood dilutions, we found this technique obstructive to the successful administration of enemas. At dilutions containing 30% DSB, we found an increased incidence of digestive tract abrasion with our technique. This observation was easily made with the appearance of red-tinged medium intermixing with the mosquito's hemocoel upon inoculation. Furthermore, we observed a significant elevation in mortality (<80%) in populations receiving these solutions (data not shown). The consequence of using enema solutions without blood components includes reduced protease activity (von Dungern and Briegel 2001) and aberrant vitellogenesis that is almost exclusively dependent upon blood meal digestion.

These physiological changes were not considered significant factors for these experiments because CHIKV is not transmitted vertically and this was not an objective of the study. Additionally, there is no indication that the administration of a blood-free enema solution, as long as it is osmotically correct, will have any ill effect on PM formation. Both Berner et al. (1983) and Briegel and Lea (1975) observed a diminished PM formation in mosquitoes correspondent to the total concentration of protein in the administered enema. Granted, the MEMα-based solutions administered by enema contained only a minimal volume of protein derived from the 10% FBS content, but no ill affect was observed, and by 7 dpi digestion/absorption of all contents of the midgut was observed.

CHIKV clearly infects the posterior midgut of the infected mosquito, whether by feeding or enema inoculation (Fig. 5). Both CHIKV-fed and enema-infected mosquitoes revealed profuse infections in the posterior midgut at 14 dpi. For the enema-infected group, this indicated that the inoculation process successfully infected cells of the digestive tract from the anus to the anterior midgut and that the exposure did not damage these tissues with the force associated with this technique. This result and the failed observation of infected tissues outside of the digestive tract also corroborates that the infection process was initiated from the luminal side of the midgut. Although no differences in the cellular content of the anterior and posterior midgut have been reported, it has been postulated that infection with the alphaviruses Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) is initiated in the posterior midgut and proceeds in an anterior direction (Weaver et al. 1988, Smith et al. 2008). However, in contrast to the work done with EEEV and VEEV, we found that enema delivery identifies populations of anterior midgut epithelial cells that appear highly susceptible to CHIKV infection (Fig. 4). The brilliant foci observed at 14 dpi in the enema-infected mosquitoes imply an early and sustainable CHIKV infection in the mesenteronal epithelial cells.

These observations correlate with previous studies, suggesting that virus dissemination can occur in the anterior midgut and tracheal cells of vectors competent to specific viruses (Romoser et al. 1987, Romoser et al. 2004). These results in no way imply a uniformity of distribution of cells susceptible to all Alphaviruses, rather that CHIKV can successfully and nonspecifically infect the entirety of the midgut, facilitating potentially rapid dissemination with little deference to an innate midgut infection barrier. Last, due to the opposing movement of infectious solution across the midgut expected with enema inoculation, it is not surprising that a higher concentration of virus particles deposited on the anterior midgut resulting in the observed increase of GFP expression. However, these observations do not implicate the anterior midgut as the sole location that CHIKV escapes the mosquito midgut.

Conclusion

This report is the first to describe enema delivery of a virus to Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. The identification of whether or not a population of midgut mesenteronal epithelial cells in the anterior or posterior sections of the midgut is more susceptible to CHIKV infection has been an unanswered question. We clearly provide evidence that demonstrates the presence of a subpopulation of cells in the anterior midgut that are prone to CHIKV infection, but that the infection is certainly not limited to that region of the midgut. The provided images demonstrate a cohesive infection process in which minimal intrusion and little to no damage was done to the intestinal tract of the mosquito. Future studies employing the administration of enemas to mosquitoes will take the measure of vector survivability postinoculation at time points greater than 14 dpi as well as the transmission potential of the enema-infected vector(s) by saliva collection and analysis. Additionally, it would be interesting to study the effect that this technique has on PM development and whether or not an artificial protein solution might elicit authentic PM development to more accurately mimic the natural infection process.

This technique has clearly been shown to have numerous applications in the manipulation of arbovirus vectors, such as ticks and mosquitoes, and offers a clear advantage to intrathoracic injection where the injected material bypasses the midgut and directly infects secondary target tissues in the hemocoel. Furthermore, IT injection damages the semirigid thorax and the attached flight muscles affecting the resting tension of these flight muscles, ultimately interfering with the initiation of flight and wing beat (Roeder 1951). Injection of materials by enema injection has not been demonstrated to cause this in mosquitoes. The techniques described here would be well-suited to investigate other infection processes of other viruses to include the potential replication of either virus or vaccine strains that do not typically infect mosquitoes when administered orally. Additionally, enema delivery of pathogens such as Plasmodium spp. may also be used to further evaluate and characterize the interaction between the parasite and the midgut cells in the context of the vectors innate physiologic response.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jing Huang for her invaluable knowledge of mosquito manipulation and her persistent efforts to assist in the administration of enemas to the mosquitoes. The CHIK LR 5′ GFP plasmid was developed by Konstantin Tsetsarkin for these experiments. This work was in part supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R21 A1073389 (to S.H.) and J.T.N. was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Department's Long Term Healthcare Education and Training program.

Author Disclosure Statement

John T. Nuckols, Sarah A. Ziegler, Yan-Jang Scott Huang, Alex J. McAuley, Dana L. Vanlandingham, Marc J. Klowden, Heidi Spratt and Robert A. Davey have no competing financial interests. Stephen Higgs is the Editor-in-Chief of Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases.

References

- Berner R. Rudin W. Hecker H. Peritrophic membranes, protease activity in the midgut of the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi (Liston) (Insecta: Diptera) under normal and experimental conditions. J Ultrastruct Res. 1983;83:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(83)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel H. Excretion of proteolytic enzymes by Aedes aegypti after a blood meal. J Insect Physiol. 1975;21:1681–1684. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(75)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel H. Lea AO. Relationship between protein and proteolytic activity in the midgut of mosquitoes. J Insect Physiol. 1975;21:1597–1604. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(75)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN. The Biology of Mosquitoes: Development, Nutrition and Reproduction. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1992. pp. 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Doi R. Studies on the mode of development of Japanese encephalitis virus in some groups of mosquitoes by the fluorescent antibody technique. Japanese J Exp Med. 1970;40:101–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi R. Shirasaki A. Sasa M. The mode of development of Japanese encephalitis virus in the mosquito Culex tritaeniorhynchus summorosus as observed by the fluorescent antibody technique. Japanese J Exp Med. 1967;37:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard YA. Klingler KA. Higgs S. West Nile virus dissemination and tissue tropisms in orally infected Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2004;4:109–122. doi: 10.1089/1530366041210729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould EA. Gallian P. De Lamballerie X. Charrel RN. First cases of autochthonous dengue fever and chikungunya fever in France: From bad dream to reality! Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1702–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guptavanij P. Venard CE. A radiographic study of the oesophageal diverticula and stomach of Aedes aegypti (L.) Mosq News. 1965;25:288–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JL. Susceptibility and resistance of vector mosquitoes. In: Monath TP, editor. The Arboviruses: Epidemiology and Ecology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc.; 1988. pp. 87–126. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. How do mosquito vectors live with their viruses? In: Gillespie SH, editor; Smith GL, editor; Osbourn A, editor. Microbe-Vector Interactions in Vector-Borne Diseases. Cambridge University Press; 2004a. pp. 103–137. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. The containment of arthropod vectors. In: Marquardt WC, editor; Kondratieff B, editor; Moore CG, editor; Freier J, editor; Hagedorn HH, editor; Black W III, editor; James AA, editor; Hemingway J, editor; Higgs S, editor. The Biology of Disease Vectors. Elsevier Academic Press; 2004b. pp. 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. Care, maintenance, and experimental infection of mosquitoes. In: Marquardt WC, et al., editors. Biology of Disease Vectors. Elsevier Academic Press; 2004c. pp. 733–739. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. Olson KE. Kamrud KI. Powers AM, et al. Viral expression systems and viral infections insects. In: Crampton JM, editor; Beard DB, editor; Louis C, editor. The Molecular Biology of Disease Vectors: A Methods Manual. London: Champman and Hall; 1997. pp. 457–483. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. Powers AM. Olson KE. Alphavirus expression systems: Applications to mosquito vector studies. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:444–452. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90098-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato N. Mueller CR. Fuchs JF. McElroy K. Wessely V. Higgs S. Christensen BM. Evaluation of the function of a type I peritrophic matrix as a physical barrier for midgut epithelium invasion by mosquito-borne pathogens in Aedes aegypti. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:701–712. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klowden MJ. Infection of Aedes aegypti with Brugia pahangi administered by enema: results of quantitative infection and loss of infective larvae during blood feeding. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75:354–358. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klowden MJ. Held GA. Bulla LA., Jr Toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis to adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:312–315. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.2.312-315.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuberski T. Fluorescent antibody studies on the development of dengue-2 virus in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1979;16:343–349. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/16.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee CE. Shustov AV. Tsetsarkin K. Frolov IV, et al. Infection, dissemination, and transmission of a West Nile virus green fluorescent protein infectious cone by Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;10:267–274. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AM. Logue CH. Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: Re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2363–2377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam JL. Scott TW. Evaluation of enemas for exposing Aedes aegypti to suspensions of dengue-2 virus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1995;11:369–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezza G. Nicoletti L. Angelini R. Romi R, et al. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: An outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet. 2007;370:1840–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder KD. Movements of the thorax and potential changes in the thoracic muscles of insects during flight. Biol Bull. 1951;100:95–106. doi: 10.2307/1538681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoser WS. Faran ME. Bailey CL. Newly recognized route of arbovirus dissemination from the mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) midgut. J Med Entomol. 1987;24:431–432. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoser WS. Wasieloski LP., Jr Pushko P. Kondig JP, et al. Evidence for arbovirus dissemination conduits from the mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) midgut. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:467–475. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyler T. Rizzo C. Finarelli AC. Po C, et al. Autochthonous chikungunya virus transmission may have occurred in Bologna, Italy, during the summer 2007 outbreak. Eur Surveill. 2008;13:118–118. doi: 10.2807/ese.13.03.08015-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR. Adams AP. Kenney JL. Wang E, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in the mosquito vector Aedes taeniorhynchus: Infection initiated by a small number of susceptible epithelial cells and a population bottleneck. Virology. 2008;372:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken W. Klowden MJ. Chambers GM. Effect of body size on host seeking and blood meal utilization in Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae): The disadvantage of being small. J Med Entomol. 1998;35:639–645. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesh RB. Arthritides caused by mosquito-borne viruses. Annu Rev Med. 1982;33:31–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.33.020182.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetsarkin K. Higgs S. McGee CE. De Lamballerie X, et al. Infectious clones of Chikungunya virus (La Reunion isolate) for vector competence studies. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2006;6:325–337. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turell MJ. Pollack RJ. Spielman A. Enema infusion technique inappropriate for evaluating viral competence of ticks. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:298–300. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dungern P. Briegel H. Enzymatic analysis of uricotelic protein catabolism in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 2001;47:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC. Scott TW. Lorenz LH. Lerdthusnee K, et al. Togavirus-associated pathologic changes in the midgut of a natural mosquito vector. J Virol. 1988;62:2083–2090. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2083-2090.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]