Abstract

Bone marrow (BM) has long been considered a potential stem cell source for cardiac repair due to its abundance and accessibility. Although previous investigations have generated cardiomyocytes from BM, yields have been low, and far less than produced from ES or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Since differentiation of pluripotent cells is difficult to control, we investigated whether BM cardiac competency could be enhanced without making cells pluripotent. From screens of various molecules that have been shown to assist iPSC production or maintain the ES cell phenotype, we identified the G9a histone methyltransferase inhibitor BIX01294 as a potential reprogramming agent for converting BM cells to a cardiac-competent phenotype. BM cells exposed to BIX01294 displayed significantly elevated expression of brachyury, Mesp1, and islet1, which are genes associated with embryonic cardiac progenitors. In contrast, BIX01294 treatment minimally affected ectodermal, endodermal, and pluripotency gene expression by BM cells. Expression of cardiac-associated genes Nkx2.5, GATA4, Hand1, Hand2, Tbx5, myocardin, and titin was enhanced 114, 76, 276, 46, 635, 123, and 5-fold in response to the cardiogenic stimulator Wnt11 when BM cells were pretreated with BIX01294. Immunofluorescent analysis demonstrated that BIX01294 exposure allowed for the subsequent display of various muscle proteins within the cells. The effect of BIX01294 on the BM cell phenotype and differentiation potential corresponded to an overall decrease in methylation of histone H3 at lysine9, which is the primary target of G9a histone methyltransferase. In summary, these data suggest that BIX01294 inhibition of chromatin methylation reprograms BM cells to a cardiac-competent progenitor phenotype.

Introduction

One of the biggest scientific advances in the past few years has been the development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which possess the phenotype and differentiation potential of embryonic stem (ES) cells [1–4]. iPSCs are generated from adult somatic cells, most often fibroblasts, by introducing various combinations of the pluripotency genes Sox2, Oct4, c-Myc, Klf4, Nanog, and LIN28 into recipient cells [5–7]. Generation of iPSCs bypasses ethical issues associated with ES cells, and provides the means to use a patient's own tissue as a source of stem cells with ES-like properties. The downside of iPSCs is that they also possess the negative properties of ES cells, which include difficulties in restraining their differentiation into a limited number of cell types and their tendency to form tumors when injected into adult tissues [8–10]. Adult tissues contain their own stem cell populations, some of which are endowed with the capability to generate differentiated phenotypes beyond the cell types that are found in their resident tissue [11–14]. For example, stem cells from bone marrow (BM) have shown a capacity to give rise to myocardial cells [15–18]. However, yields of BM-derived cardiomyocytes have been low, and far less than generated from ES cells or iPSCs [19–21].

Since differentiation of ES cells and iPSCs is difficult to control and the phenotypic potential of adult stem cells is limited, we sought an alternative approach that would expand the phenotypic capacities of adult cells to make them cardiac competent, while stopping short of making the cells pluripotent. As a starting cell population, we used progenitor cells from adult BM as a prospective source of myocardial progenitors. The direct introduction of transgenes into adult cells was avoided as a method for changing the cell phenotype due to the concern that permanent introduction of genes that enhance the phenotypic potential may compromise the function of differentiated tissue derived from the initial cell population. Instead, our efforts to broaden the differentiation potential of BM cells employed extracellular signaling factors and pharmacological reagents that have been shown to assist the production of iPSCs and/or maintain an ES cell phenotype, but in themselves are insufficient to forge a pluripotent phenotype.

Several regulatory pathways were targeted in our screen for molecules that could expand the differentiation potential of BM cells. Molecules screened in this study included modulators of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) activity, canonical Wnt and TGFβ signaling, nitric oxide production, histone deacetylation and methylation, which have been shown to either aid the acquisition and/or maintenance of a pluripotent phenotype [22–32]. These drugs and proteins were assessed for their ability to induce BM-derived cells to express markers associated with cardiac-competent progenitor cells, and allow these cells to exhibit a cardiac myocyte phenotype when subsequently cultured under conditions that were previously established for promoting cardiogenic differentiation of precardiac progenitors.

Both BM and heart are derived from the mesodermal layer of the embryo. Accordingly, treatments that broaden the differentiation potential of BM progenitor cells to produce cardiocompetent cells may be expected to express markers corresponding to precardiac cells within the embryonic mesoderm. Among the earliest markers expressed in the mesoderm are those characteristic of cardiocompetent progenitors, as the heart is the first functional organ to develop in the mammalian embryo. Thus, our initial screening of treatments that would expand the cardiac potential of BM cells was for upregulation of markers characteristic of precardiac mesoderm. Expression of the T box transcription factor brachyury is required for specification of precardiac mesoderm, although its expression extends more broadly within primary mesoderm [33,34]. Positive brachyury expression has also been used to distinguish mesodermal precursors derived from ES cells that have a cardiac potential [35]. Mesp1 is a bHLH transcription factor that emerges in the early embryo within the nascent mesoderm, most prominently in precardiac tissue, and is proposed to play a key role in the cardiac lineage specification [36–38]. Islet1 is considered the defining marker of progenitor cells in the secondary heart field [39,40], although more recent data indicated that islet1 is also exhibited by progenitors within the primary heart field [41,42].

Of the molecules tested for expanding the phenotypic potential and increasing the myocardial competency of BM cells, only BIX01294 proved useful in promoting cardiopotency. BIX01294 is a selective pharmacological inhibitor of G9a histone methyltransferase (HMTase); an enzyme that is also referred to as euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2 (EHMT2) and lysine (K) methyltransferase 1C [43]. The major substrate for G9a HMTase is histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9), which is an active site of chromatin regulation targeted by several distinct methylating enzymes [44]. Histone lysine methylation plays a significant role in organizing the chromatin structure and controlling gene transcription [45–47]. Inhibition of G9a HMTase by BIX01294 has been shown to improve the transducing efficiency of pluripotency genes for reprogramming somatic cells to iPSCs [31,48]. Here we report that treatment with BIX01294 stimulated expression of the early cardiac markers, brachyury, Mesp1, and islet1, and increased their capacity to subsequently undergo cardiac differentiation. In contrast, BIX01294 by itself displayed only negligible effect on transcription of ectodermal, endodermal, and pluripotency genes by BM cells. These data indicate that BIX01294 is able to reprogram BM cells into cardiocompetent progenitors and suggest that this pharmacological reagent may have value as a tool for generating cells for the therapeutic treatment of the heart.

Experimental Procedures

BM cell isolation

BM was collected from the hind limbs of 8–10-week C57BL/6 mice. Primary cells were obtained by flushing the BM cavities with the Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) containing 100 U/mL penicillin–100 μg/mL streptomycin (Pen/Strep; Invitrogen). BM cords were dissociated by repetitive passage through a 20-gauge needle followed by filtration through a 40-μm nylon cell sieve (Falcon Labware). Cells were resuspended at a density of 107 cells/mL in IMDM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus Pen/Strep and plated on bacterial-grade Petri dishes. For some experiments, BM cells were purified by positive selection to cell surface CD117 (c-kit) expression. Freshly harvested BM was magnetically sorted using the RoboSep Mouse CD117-Positive Selection Kit (Stem Cell Technologies). After verifying their positive expression of the CD marker, CD117+ BM cells were allowed to attach to culture dishes in IMDM/FBS, and cultured for 2 weeks before their experimental use.

Cell cultures

BM cells were grown for 14 days in IMDM/20% FBS, with fresh media provided weekly. After 2 weeks in culture, cells were serum-starved overnight in IMDM. Next day, cells were cultured in fresh IMDM/10% FBS in the presence or absence of various doses of BIX01294, CHIR99021, 1,5-naphthyridine pyrazole derivative-19 (NPy19) [49] (Stemgent), 3-bromo-7-Nitroindazole (BNI), trichostatin A (TSA; Cayman Chemical), and/or Wnt3a (PeproTech). After 2 days of treatment, cells were either harvested for RNA isolation or treated with cardiogenic inducers. Cardiomyocyte differentiation was initiated with the Wnt11-conditioned medium diluted 50:50 with IMDM/20% FBS (final concentration of FBS was 10%). The Wnt11-conditioned medium was produced from Wnt11 stably transfected QCE6 cells, as described previously [50], with the presence of the secreted Wnt11 protein being verified by immunoblotting. For immunostaining, the cells were either replated in Lab-Tek 8-well chamber slides (Nunc) or cytospun onto histology slides, as described [15,16]. The mouse ES cell line, D3 (American Type Culture Collection), was maintained in the Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 5×10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and passaged in the presence of 10 ng/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; R&D Systems). ES cells were cultured according to standard protocols [51]. For pluripotency genes, RNA was obtained from LIF-treated nondifferentiated ES cell aggregates. For early germ layer markers, RNA was obtained from 2-day LIF-minus ES cell suspension cultures. The mesoderm progenitor cell line, QCE6, which was used to verify the functional activities of the molecules screened in this study, was cultured as described [52].

Immunoblotting

For immunoblot analysis, BM cells cultured in the absence or presence of 8 μM BIX01294 were lysed in the RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1% Triton X-100) containing Mammalian ProteaseArrest protease inhibitors (G-Biosciences). The extracted protein was separated on polyacrylamide gels, transferred to the PVDF membrane, and incubated with rabbit antibodies specific to dimethyl-histone H3K9 (Cell Signaling Technology), Mesp1 (Abgent), or GAPDH (Abcam). Proteins were detected using the alkaline phosphatase-coupled secondary antibody (Sigma) and the PhosphaGLO Reserve AP Substrate (KPL, Inc.).

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent labeling was performed using previously described protocols [15,16,50]. For GATA4 staining, cells were formalin fixed, and then permeabilized for 10 min with 0.25% Triton-X100/PBS. After multiple PBS washes, nonspecific binding sites were blocked by overnight incubation with PBS+10% goat serum at 4°C. The next day, the rabbit anti-GATA4 antibody (ab61170; Abcam) was diluted with a 1:1,000 blocking solution and applied to the slides overnight at 4°C. Thereafter, cells were washed extensively with PBS, and then incubated with a 1:100 dilution of goat anti-rabbit DyLight 488-conjugated IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) secondary antibody in Triton-X100/PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Afterward, cells were counterstained with fluorescent-tagged wheat germ agglutinin (Vector Laboratories) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenyindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) to visualize individual cells and nuclei.

The protocol for titin, desmin, sarcomeric α-actin (SA-actin), and sarcomeric α-actinin staining was similar to the above, except for several modifications. Cells were fixed with methanol for 10 min at −20°C, washed several times with PBS, and then blocked by overnight incubation with either 5% BSA/PBS blocking solution for antibodies specific to titin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), desmin, SA-actin, and the α-actinin antibody (Sigma). DyLight 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used to visualize staining.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification

Total RNA was obtained from BM and ES cell cultures according to the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) protocol. RNA was reverse-transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse-Transcription Kit (Applied BioSystems). Amplified DNA from endpoint reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was run in parallel with molecular weight markers on DNA agar (Marine BioProducts) gels to verify the size of the DNA bands. Comparative quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis for each gene of interest was performed on the StepOne Plus qPCR system (Applied BioSystems) using the Perfecta SYBR green FastMix Rox qPCR master mix (Quanta Biosciences). Validated primer pairs (Table 1) were either designed with the Primer 3 Express software (Applied BioSystems) or obtained from the Harvard Medical School PrimerBank. Relative gene expression levels were estimated by the ΔΔCt method using GAPDH as the housekeeping gene. Comparisons between multiple groups were determined with Bonferroni-corrected analysis of variance testing, except for data in Fig. 5, where statistical difference between 2 groups was evaluated using the Mann–Whitney test. Statistical significance, which was defined as P<0.05, was calculated using the InStat statistical application (GraphPad Software). All error bars correspond to standard error of the mean.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Primers Used for Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of RNA Expression

| Gene | Forward and reverse primers | Amplicon length | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-fetoprotein | GCATTGCACGAAAATGAGTTTG GGGTAAAGGTGATGGTAGCTATGCTA |

100 | NM_007423 |

| β-myosin heavy chain | CTAAGAGGGTCATCCAATATTTTGC GGTTGGCTTGGATGATTTGA |

110 | NM_080728 |

| Brachyury | AAGAACGGCAGGAGGATGTTC GTTGTCAGCCGTCACGAAGTC |

102 | NM_009309 |

| c-Myc | GCCCCTAGTGCTGCATGAG CCACAGACACCACATCAATTTCTT |

95 | NM_010849.4 |

| FoxA2 | GCAAGAAGACCGCTCCTG CTCGCTTGTGCTCCTGAC |

132 | NM_010446 |

| FoxJ1 | ATCACTCTGTCGGCCATCTAC GCAGGGTGGATGTGGACTG |

245 | NM_008240 |

| GAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

123 | NM_008084 |

| Gata4 | CCCTACCCAGCCTACATGG ACATATCGAGATTGGGGTGTCT |

139 | NM_008092 |

| Islet1 | CCAAGTGCAGCATAGGCTTCA CAGGCTACACAGCGGAAACA |

91 | NM_021459 |

| Klf4 | GTGCCCCGACTAACCGTTG GTCGTTGAACTCCTCGGTCT |

185 | NM_010637.2 |

| Mesp1 | CTGTACCATTCCAACCCTCCTT GCTTGTGCCTGCTTCATCTTT |

74 | NM_008588 |

| MSX1 | AAACCCCTTGCTACACACTTCCT AAACCTAGACACTTCCGACCATTC |

100 | NM_010835 |

| Nanog | TCCATTCTGAACCTGAGCTATAAGC GTGCTGAGCCCTTCTGAATCA |

127 | NM_028016 |

| Nkx2.5 | TCTCCGATCCATCCCACTTTA TCCCGGTCCTAGTGTGGAATC |

104 | NM_008700 |

| Oct4 | GGAGTCTGGAGACCATGTTTCTG GAACCATACTCGAACCACATCCTT |

107 | NM_013633.2 |

| PAX2 | AAGCCCGGAGTGATTGGTG GTTCTGTCGCTTGTATTCGGC |

84 | NM_011037 |

| PAX6 | CATACCCAGTGTGTCATCAATAAACA CGTTCAACATCCTTAGTTTATCATACATG |

104 | NM_013627 |

| Runx2 | GACTGTGGTTACCGTCATGGC ACTTGGTTTTTCATAACAGCGGA |

84 | NM_001146038 |

| Sox2 | GCGGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCC CGGGAAGCGTGTACTTATCCTT |

157 | NM_011443 |

| Titin | GGAAGCGTCTCGTCTCAGTC CATGCTCGCAAACTTCATTTCAG |

114 | NM_011652 |

| TRPS1 | ACTGAGTAAACCCAAAGGTGACT GCCATAGTAACCGTATCCACAG |

112 | NM_032000 |

| TTF1 | TGGAGAACCTGCTAGAGACTTC TGTTTCACGCACTTTTGCTGA |

92 | NM_009442 |

| WT1 | AGCACGGTCACTTTCGACG GTTTGAAGGAATGGTTGGGGAA |

85 | NM_144783 |

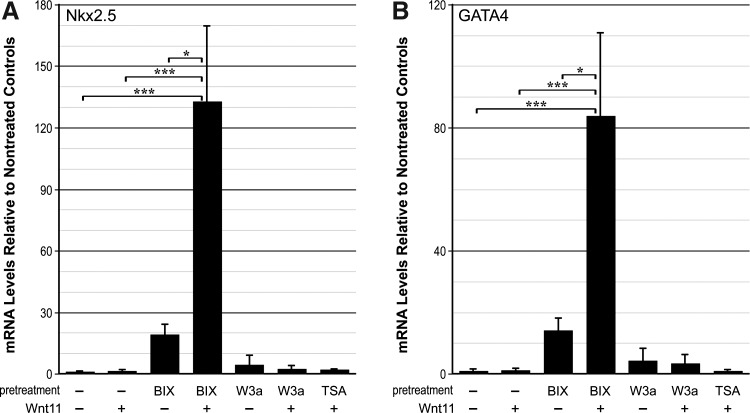

FIG. 5.

Cardiomyogenic competency of BM-derived cells. BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 8 μM BIX01294, 50 ng/mL Wnt3a, or 50 nM TSA for 48 h before the addition of fresh media by itself or supplemented with Wnt11. Seven days later, cultures were harvested for RNA, and assayed by real-time qPCR. (A, B) PCR analyses of Nkx2.5 and GATA4 expression, respectively. Expression of these cardiac genes by BM cells was minimal in nontreated and Wnt3a or TSA-treated cultures, regardless of whether the cultures were subsequently exposed to the cardiogenic stimulating factor Wnt11. In contrast, BIX01294 pretreatment did yield small increases of expression over basal levels. However, when BM cells were pretreated with BIX01294, subsequent exposure to Wnt11 enhanced expression of Nkx2.5 and GATA4 by >132-fold and 82-fold, respectively. BIX, BIX01294; W3a, Wnt3a *P<0.05 and ***p<0.001.

Results

Upregulation of mesodermal and cardiac progenitor markers in BM cells

BM cells used in this study were obtained from adult mice by selection on hydrophobic, bacterial-grade plastic dishes for 2 weeks. As reported [15,16], these conditions produce enriched populations of myeloid progenitor cells, which demonstrated a limited cardiac competency in both culture assays and when injected into the embryonic heart. Multiple small molecule inhibitors and signaling proteins were screened for their utility in coaxing a cardiopotent phenotype from these cultured selected BM cells, which will be referred to as long-term (LT) BM cells. Among molecules analyzed for their effect on the BM phenotype were the selective GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021, the canonical Wnt protein Wnt3a, TGFβ receptor antagonist NPy19, broad-range inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase (BNI) and histone deacetylase activities (TSA), and the G9a HMTase inhibitor BIX01294. LT-BM cells were exposed to the pharmacological reagents at a wide range of doses and exposure times. Cultures were then analyzed by real-time qPCR for expression of genes corresponding to the myocardial lineage.

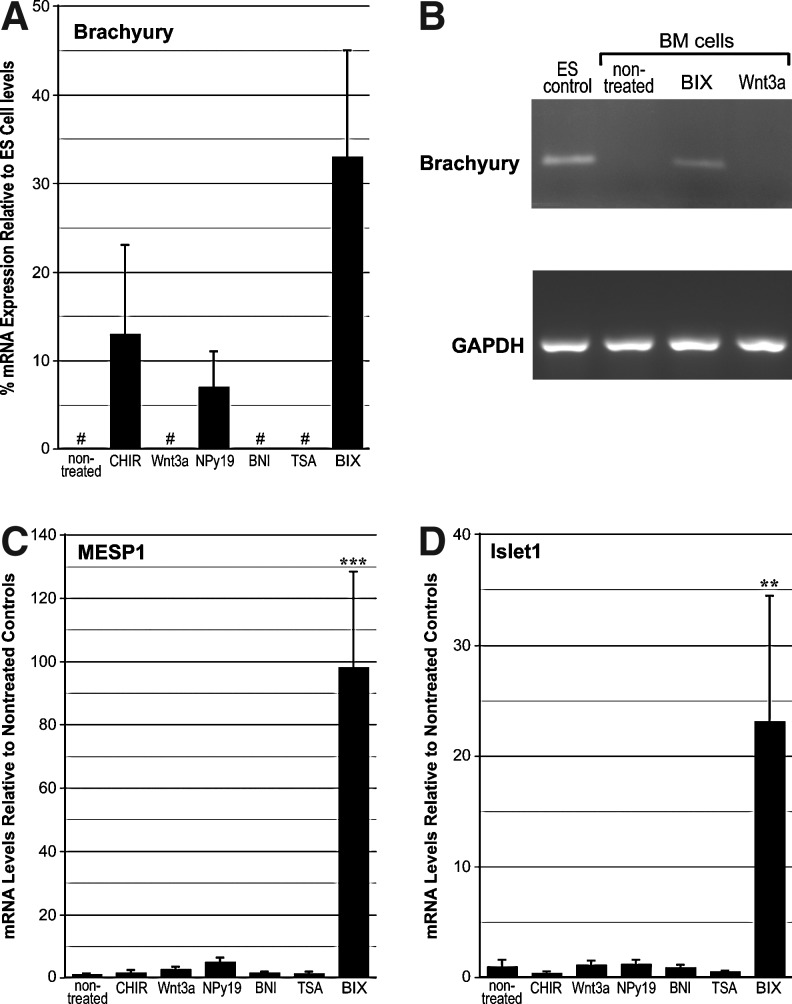

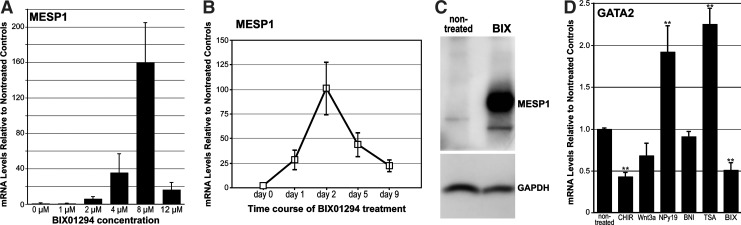

Brachyury expression was not detected in LT-BM cells that were nontreated or exposed to either Wnt3a, BNI, or TSA. Both CHIR99021 and NPy19 promoted brachyury transcription, although to a lesser degree than BIX01294 (Fig. 1A). That brachyury expression in response to BIX01294 was appreciable was verified by a comparison to levels exhibited in differentiating ES cell cultures (Fig. 1A) and visible amplification of brachyury mRNA in endpoint PCR (Fig. 1B). Mesp1 mRNA levels in response to an optimum dose of BIX01294 produced a >97-fold enhancement as compared to nontreated controls (Fig. 1C). None of the other treatments produced any significant enhancement of Mesp1 expression (Fig. 1C). A similar result was obtained with islet1 (Fig. 1D), as BIX01294 exposure generated a 23-fold increase in mRNA expression as compared to nontreated controls. No other treatment that LT-BM cells were subjected to produced any measurable enhancement of islet1 expression (Fig. 1D). Dose–response analysis determined that the optimum concentration of BIX01294 for promoting expression of these cardiac progenitor genes in this cell population was 8 μM (Fig. 2A). Time-course studies indicated that the maximum induction of gene expression by BIX01294 was obtained within 48 h of culture, and did not increase with extended incubation periods (Fig. 2B). BIX01294 induction of Mesp1 expression was verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 1.

Mesodermal and cardiac progenitor gene expression in bone marrow (BM)-derived cells. Long-term (LT)-BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of the indicated molecules over a range of concentrations, with the experiments displayed summarizing results using optimized doses of CHIR99021 (1 μM), Wnt3a (50 ng/mL), 1,5-naphthyridine pyrazole derivative-19 (NPy19, 1 μM), 3-bromo-7-nitroindazole (BNI, 1 μM), trichostatin A (TSA, 50 nM), or BIX01294 (8 μM) for 48 h before RNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. (A) Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of brachyury expression. Because brachyury expression was not detected in nontreated BM cells, levels generated in treated BM cultures were compared to expression obtained in embryonic stem (ES) cells. BIX01294 treatment generated the highest levels of brachyury expression, although CHIR99021 and NPy19 also were able to induce transcription of this gene. “#” refers to RNA levels that were undetectable by PCR amplification. (B) End-point reverse transcriptase PCR verifying the induction of brachyury gene expression in response to BIX01294, while being absent in nontreated and Wnt3a-treated BM cells. Amplified ES cell RNA is provided as positive control for brachyury expression. Amplification of the housekeeping gene GAPDH verifies equal template concentrations for each sample. (C, D) Real-time qPCR analysis of Mesp1 and islet1 expression, respectively. For both genes, nontreated LT-BM cells exhibited minimal levels of expression. None of the treatments produced any significant enhancement of Mesp1 or islet1 transcription, except for BIX01294, which generated >97-fold and 23-fold enhancement in expression levels of Mesp1 and islet1, respectively. For Mesp1 and islet1 expression, data was normalized to levels measured in nontreated cells. Error bars correspond to standard error of the mean from 25 biological repeats for BIX01294 and control groups, and 3–5 biological repeats for the other treatments. Asterisks centered on individual bars indicate statistical significance as compared to nontreated cultures. **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. BIX, BIX01294; CHIR, CHIR99021.

FIG. 2.

BIX01294 promotes cardiac gene expression in BM cells. (A) LT-BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of various doses of BIX01294 for 48 h and assayed for Mesp1 expression by qPCR. Maximum Mesp1 expression in LT-BM cell cultures was obtained at 8 μM concentration of BIX01294. (B) LT-BM cells were cultured in the presence of 8 μM BIX01294 for up to 9 days and assayed for Mesp1 gene expression. Optimal responses were obtained at 48 h BIX01294 treatment. (C) Parallel LT-BM cultures that were cultured in the absence or presence of 8 μM BIX01294 for 48 h were immunoblotted for Mesp1 (top) and GAPDH (bottom) protein. Note the induction of Mesp1 protein in response to BIX01294 exposure. (D) LT-BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of CHIR99021, Wnt3a, NPy19, BNI, TSA, or BIX01294 for 48 h before RNA isolation and qPCR analysis of GATA2 expression. Among these various treatments, only CHIR99021 and BIX01294 significantly reduced GATA2 expression, with the latter reagent decreasing the transcription of the GATA2 gene by 50%. Asterisks indicate statistical significance as compared to nontreated controls, with ** indicating P<0.01.

Since the BM cells used in this study normally exhibit blood cell potential, we examined the various culture treatments for their effect on the expression of the hematopoietic progenitor marker, GATA2. Of these treatments, the most pronounced effect was exhibited by BIX01294, which produced a statistically significant 50% reduction of GATA2 expression (Fig. 2D). Among the other treatments provided the cells, only CHIR99021 produced a significant reduction in GATA2 expression by the cells, although both NPy19 and TSA produced mild, but statistically significant upregulation of GATA2 (Fig. 2D).

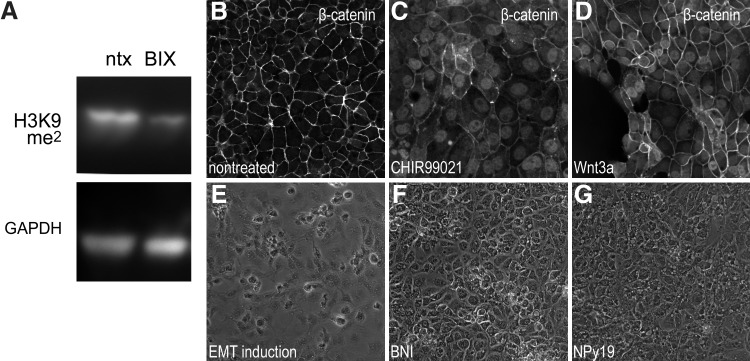

To ascertain whether changes in the BM cell phenotype that occurred in response to BIX01294 correlated to its inhibition of G9a HMTase activity, we compared the methylation state of histone proteins isolated from nontreated and BIX01294-treated BM cultures. Since the principal target of G9a HMTase is histone H3K9, we examined methylation at this histone residue using antibodies that recognize histone H3 only when methylated at H3K9. Immunoblotting demonstrated that BIX01294 treatment of LT-BM cells visibly reduced H3K9 methylation (Fig. 3A), confirming the activity of BIX01294 in promoting specific chromatin modifications. For the other molecules used in this study, we performed positive control experiments of previously described activities [49,53–55] to ensure that they were functionally active despite their inability to promote expression of cardiac progenitor genes. For example, both CHIR99021 and Wnt3a provoked the nuclear localization of β-catenin (Fig. 3B–D), BNI inhibited epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformations (Fig. 3E–G), and the TGFβ receptor antagonist NPy19 inhibited TGFβ signaling (Fig. 3F–H). Thus, despite being fully functional, none of the other molecules that were part of our molecular screening exhibited the unique capacity of BIX01294 as a promoter of cardiac gene expression.

FIG. 3.

Activities of signaling molecules used to treat BM cells. (A) Effect of G9a histone methyltransferase (HMTase) inhibition on BM cells. Immunoblot of protein isolated from nontreated and BIX01294-treated BM-LT cells, showing that methylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9) is reduced upon exposure to the G9a HMTase inhibitor BIX01294. Blotting for the housekeeping gene GAPDH verifies equal amounts of protein were added for each sample. (B–G) The other molecules screened in this study were subsequently tested using standard assays on cell lines to verify that they were functionally active despite their inability to enhance the phenotypic potential of BM cells. (B–D) The mesoderm progenitor cell line QCE6 immunostained for β-catenin. (B) Nontreated cultures exhibit β-catenin strictly at cell borders. (C, D) However, in response to the glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibitor CHIR99021 or the canonical Wnt protein Wnt3a, respectively, β-catenin becomes localized to the nucleus. (E) Treatment with retinoic acid, FGF2, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 induces QCE6 cells to undergo an epithelial -to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT). (F) As described for embryonic cells [55], blockage of nitric oxide synthase using BNI prevents the transformation to a mesenchymal phenotype. (G) The TGFβ mediated EMT of QCE6 cells was suppressed by the TGFβ receptor antagonist NPy19.

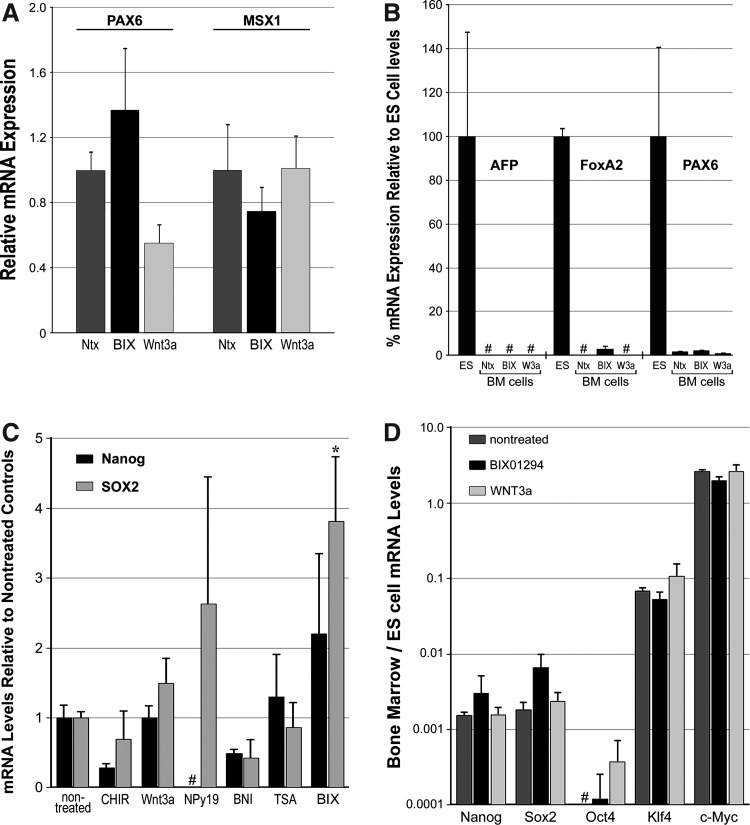

Effect of BIX01294 on ectodermal, endodermal, and pluripotency gene expression in BM cells

In contrast to the upregulation of mesodermal and cardiac progenitor markers in response to BIX01294, expression of ectodermal- or endodermal-associated genes in LT-BM cells were minimally affected by BIX01294 treatments (Fig. 4A, B). PAX6 and MSX1 are primary ectodermal markers that contribute to the neural tube and skin development [56–59]. Although low-level transcription of both PAX6 and MSX1 was exhibited by nontreated LT-BM cells, exposure to BIX01294 or the other molecules used in this study (e.g., Wnt3a) were unable to enhance expression of these ectoderm-affiliated genes (Fig. 4A). Less prominent still was BM expression of early endodermal genes α-fetoprotein (AFP) and forkhead box protein A2 (FoxA2) [60–62]. AFP expression by LT-BM cells was not discernible in cultures that were nontreated, BIX01294-treated, or exposed to the other molecular reagents (e.g., Wnt3a), although this gene was readily detected in control ES cell cultures (Fig. 4B). FoxA2 transcription was also undetectable in nontreated LT-BM cultures. Despite an upregulation of FoxA2 mRNA in response to BIX01294, the level of expression by the BM cells was far less than observed in control ES cells (Fig. 4B). Moreover, when BM gene expression is presented in proportion to levels received from ES cells, the maximum amount of FoxA2 transcription obtained from the BM cultures is on par with that of the ectodermal marker, Pax6, and far less than the BIX01294-induced enhancement of the mesodermal marker, brachyury (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 4.

Ectodermal, endodermal, and pluripotency gene expression in BM-derived cells. (A, B) LT-BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 8 μM BIX01294 or 50 ng/mL Wnt3a for 48 h before RNA isolation and qPCR analysis. (A) Expression of the ectodermal markers PAX6 and MSX1 by BM cells were unaffected by BIX01294 or Wnt3a treatments. Small variations received for PAX6 and MSX1 RNA amplification among treatment groups were not statistically significant. Error bars correspond to standard error of the mean from 3 individual experiments. (B) Expression of marker genes in BM cell cultures as compared to levels obtained in ES cells. The endodermal marker α-fetoprotein (AFP) was not detected in BM cells, in either nontreated conditions or following exposure to BIX01294 or Wnt3a. The endodermal gene forkhead box protein A2 (FoxA2) was also not detected in nontreated and Wnt3a-treated BM cell cultures. A slight stimulation of FoxA2 transcription was observed in response to BIX01294 exposure. However, levels of FoxA2 RNA generated by BM cells were much smaller than exhibited by ES cells, and were comparable in scope to the minimal levels observed with the ectodermal marker PAX6. Moreover, relative endodermal and ectodermal gene activation was far less than observed for the mesodermal gene brachyury (see Fig. 1A). Ntx, nontreated; BIX, BIX01294; W3a, Wnt3a. (C) LT-BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of CHIR99021, Wnt3a, NPy19, BNI, TSA, or BIX01294 for 48 h before RNA isolation and PCR analysis of pluripotency gene expression. None of the treatments produced any significant stimulation of nanog or Sox2 expression except BIX01294, which slightly enhanced expression of Sox2. (D) When the BM cell PCR data shown in (C) is displayed as a function of the level of gene expression exhibited by parallel cultures of nondifferentiated mouse ES cells, it becomes apparent that the levels of nanog and Sox2 that are elicited from BM cells are not substantial. Although both BIX01294 and Wnt3a induced low levels of Oct4 mRNA, which were not apparent in nontreated cultures, the maximum levels generated from BM cell treatments was >3,000-fold less than expression produced by ES cells. None of the treatments stimulated transcription of pluripotency genes Klf4 and c-Myc, although both genes displayed levels of expression in nontreated BM cells that were comparable to that exhibited by the ES cells. “#” refers to RNA levels that were undetectable by PCR amplification. Asterisks indicate statistical significance as compared to nontreated controls, with * indicating P<0.05.

Since BIX01294 has been characterized for its ability to assist iPSC production, we examined whether the treatments described above would enhance BM cell pluripotency gene expression. LT-BM cells were treated with either CHIR99021, Wnt3a, NPy19, BNI, TSA, or BIX01294, with real-time qPCR used to examine their relative expression of the pluripotency genes nanog, sox2, oct4, Klf4, and cMyc, as compared to the nondifferentiated mouse ES cell line D3 (Fig. 4C, D). The effect of these reagents on pluripotency gene expression was slight. The greatest stimulation of nanog and sox2 was by BIX01294, which enhanced expression of these genes 2.2- and 3.8-fold, as compared to nontreated LT-BM cells (Fig. 4C). Yet, the juxtaposition of pluripotency gene expression in BM cell and ES cell cultures revealed that the maximum levels of nanog and sox2 expression obtained in BM cells was 500- and 140-fold less than exhibited by ES cells (Fig. 4D). Both BIX01294 and Wnt3a were able to induce measurable levels of oct4 expression that was not exhibited by nontreated BM cells, but these levels of oct4 were >3,000-fold less than produced by ES cells (Fig. 4D). While none of the treatments enhanced expression of Klf4 and cMyc, the levels of mRNA exhibited by these 2 genes in nontreated LT-BM cells were comparable to that displayed by nondifferentiated ES cells (Fig. 4D).

Pretreatment of BM cells with BIX01294 promotes their cardiomyogenic competency

The above data showed that only BIX01294, among the reagents tested, provoked expression of mesodermal and cardiac progenitor markers in LT-BM cells (Figs. 1 and 2). Next, we examined whether BIX01294-treated cells would exhibit markers of differentiated cardiomyocytes or make the cells responsive to inducers of cardiogenic differentiation. Neither nontreated control LT-BM cells nor cells treated with the various molecular reagents used in this study expressed genes associated with differentiated cardiac myocytes (Fig. 5). The only exception among the treatments was exposure to BIX01294, which prompted small increases in expression of the cardiac-associated transcription factors, Nkx2.5 and GATA4, by the BM cell cultures (Fig. 5A, B). To examine the ability of LT-BM cells to respond to cardiogenic stimuli, nontreated, BIX01294, Wnt3a, or TSA pretreated cells were subsequently incubated with the well- defined cardiogenic inducer Wnt11 [50,63,64]—a noncanonical Wnt that possesses signaling properties distinct from canonical Wnts, such as Wnt3a [53,65]. By itself, Wnt11 was ineffective in stimulating cardiac gene expression by BM cells (Fig. 5). Pretreating LT-BM cells with Wnt3a or TSA also had no effect on their cardiogenic capacity, as the cells remained unresponsive to Wnt11 exposure. However, pretreatment with BIX01294 dramatically enhanced the cardiac competency of the BM cells, as subsequent exposure to Wnt11 amplified expression of Nkx2.5 and GATA4 mRNA by >132-fold and 82-fold, respectively (Fig. 5A, B).

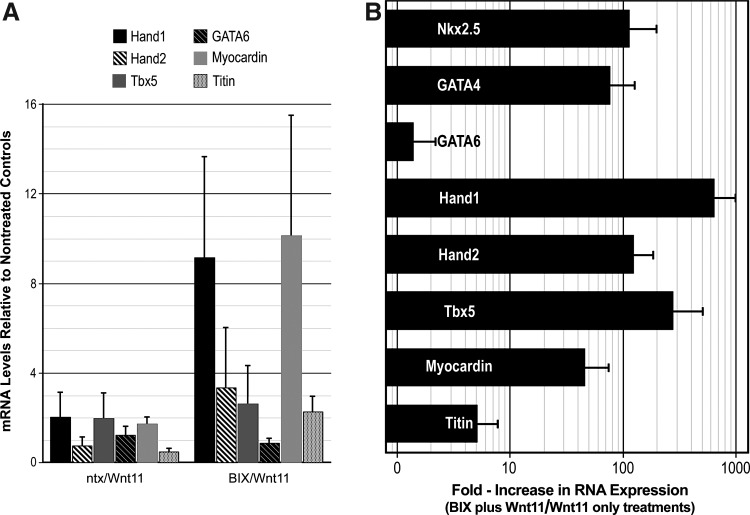

Other cardiomyocyte-associated genes, including Hand1, Hand2, Tbx5, GATA6, myocardin, and titin, were also tested in the cultures. Interestingly, these genes were either not enhanced or only minimally upregulated in response to the 2-step BIX01294/Wnt11 treatment (Fig. 6A). In our efforts to produce a more complete display of early cardiomyocyte genes within the cultures, we investigated whether the heterogeneous nature of the starting population may have hindered their subsequent differentiation in response to Wnt11. Up to this point, we used total BM selected on hydrophobic dishes for 2 weeks, as the starting cell population for the BIX01294 studies. Here instead, we first sorted newly harvested BM for the progenitor cell marker, CD117 (c-kit), before a 2-week selection procedure in culture and their subsequent utilization for experimentation. Using the same protocol described above for LT-BM cells, CD117-enriched LT-BM cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 8 μM BIX01294 for 48 h, before exposure to Wnt11 for 7 days in culture. As shown in Fig. 6B, the CD117 enrichment step yielded cultures that produced a more comprehensive display of cardiac gene expression. In concurrence with its stimulation of Nkx2.5 and GATA4 gene expression, the 2-step BIX01294/Wnt11 treatment provoked increases of >720, 135, 278, 48, and 5-fold higher levels of Hand1, Hand2, Tbx5, myocardin, and titin expression, respectively, as compared to cultures treated with Wnt11 without BIX01294 pretreatment. Among the cardiac-associated genes tested, only GATA6 levels remained unaffected by the BIX01294/Wnt11 treatment protocol (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Cardiac differentiation of BM-derived cells. (A) LT-BM cultures assayed for Nkx2.5 and GATA4 in Fig. 5 were additionally assayed for the cardiac-associated genes Hand1, Hand2, Tbx5, GATA6, myocardin, and titin. BIX01294-pretreatment provided for a mild stimulation of Hand1 and myocardin expression in response to Wnt11. However, neither Hand2, Tbx5, GATA6 nor titin gene expression was enhanced when LT-BM cells were subjected to these culture conditions. (B) In contrast, a more vibrant cardiac gene response was observed with CD117-enriched LT-BM cells. Among the genes tested, only GATA6 did not display a statistically significant increase in response to the BIX01294/Wnt11 2-step treatment. As shown in log scale, Nkx2.5, GATA4, Hand1, Hand2, Tbx5, myocardin, and titin, displayed a 114, 76, 276, 46, 635, 123 and 5-fold increased response to Wnt11 when pretreated with BIX01294.

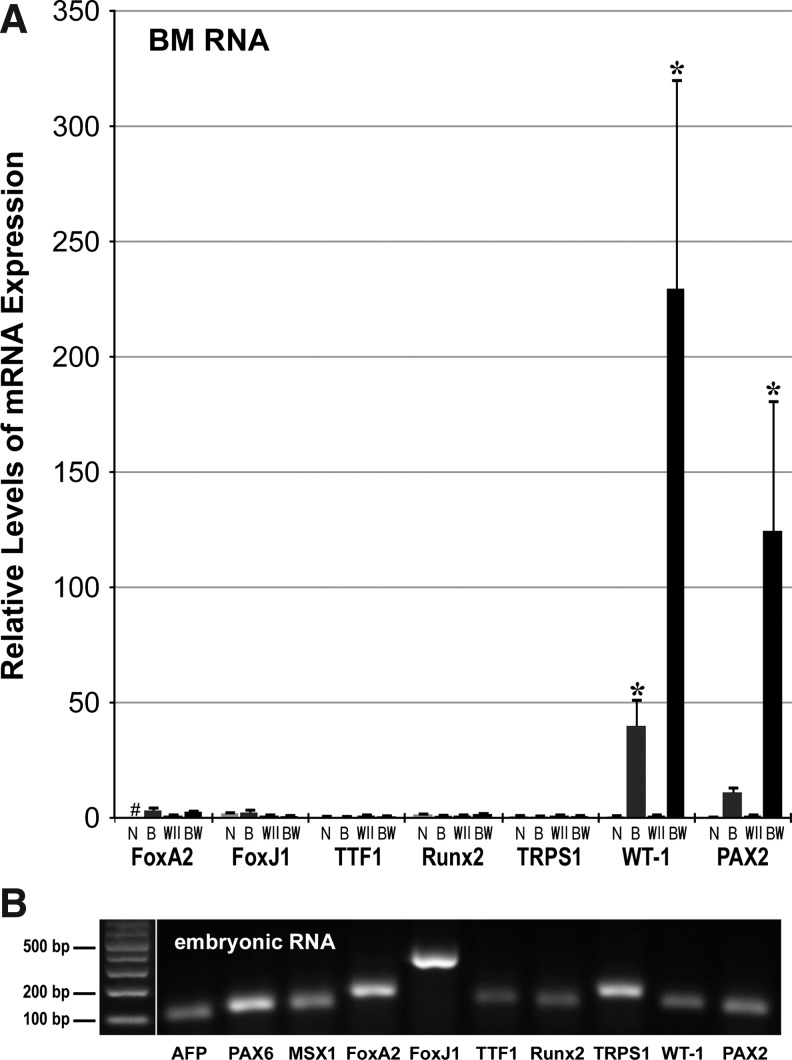

BM cells were also examined for upregulation of noncardiac genes in response to the 2-step BIX01294/Wnt11 treatment. Expression of the pluripotency genes nanog, Sox2, Oct4, Klf4, and cMyc were not enhanced by this treatment (not shown). BIX01294/Wnt11 also did not stimulate expression of the ectodermal and endodermal markers PAX6, MSX1, AFP, and FoxA2 (Fig. 7). Of note was the lack of an increased response by FoxA2, which is highly expressed throughout the development of endoderm-derived lung, and whose development is regulated by Wnt11 [66–68]. In accordance, neither of the prominent lung marker genes FoxJ1 and TTF1 [67] were upregulated in BM cells in response to Wnt11 with or without prior BIX01294 exposure (Fig. 7). As a follow-up, we also examined gene expression associated with other noncardiac mesoderm-derived tissues, whose development is Wnt11 dependent. As shown in Fig. 7, BIX01294 pretreatment was unable to promote transcription of the perichondrial genes Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and Tricho-rhino-phalangeal syndrome Type 1 (TRPS1) [69,70]. However, we did observe significant Wnt11-mediated induction in expression of the kidney markers Wilms tumor antigen (WT-1) and PAX2 [71–73], when the cultures were pre-exposed to BIX01294 (Fig. 7). It may be noted that WT-1 expression is also associated with an epicardial lineage with cardiomyocyte differentiation potential [74].

FIG. 7.

BIX01294/Wnt11 stimulation of noncardiac gene expression. (A) BM cells were cultured for 48 h minus/plus 8 μM BIX01294, followed by 7 days in the absence or presence of Wnt11, before RNA isolation and qPCR amplification. These treatments of the BM cells are indicated by the following abbreviations: N, nontreated; B, BIX01294 only; W11, Wnt11 only, and BW, BIX01294/Wnt11 double treatment. Not shown are AFP, PAX6, and MSX1 whose expression was unaltered by these treatments. Also unaffected by these treatments were expression off the lung markers FoxA2, FoxJ1, and TTF1, and the perichondrial markers Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and Tricho-rhino-phalangeal syndrome Type 1 (TRPS1). In contrast, genes associated with the developing kidney—WT-1 and PAX2—were significantly increased in response to Wnt11, when pretreated with BIX01294. “#” refers to RNA levels that were undetectable by PCR amplification. Asterisks indicate statistical significance as compared to nontreated controls, with * indicating P<0.05. (B) Mouse embryonic RNA (days 10–12) was amplified for each primer pair to verify that negative amplification for BM cell RNA was not due to primer inefficiency. Left lane displays DNA molecular weight markers, with band sizes indicated.

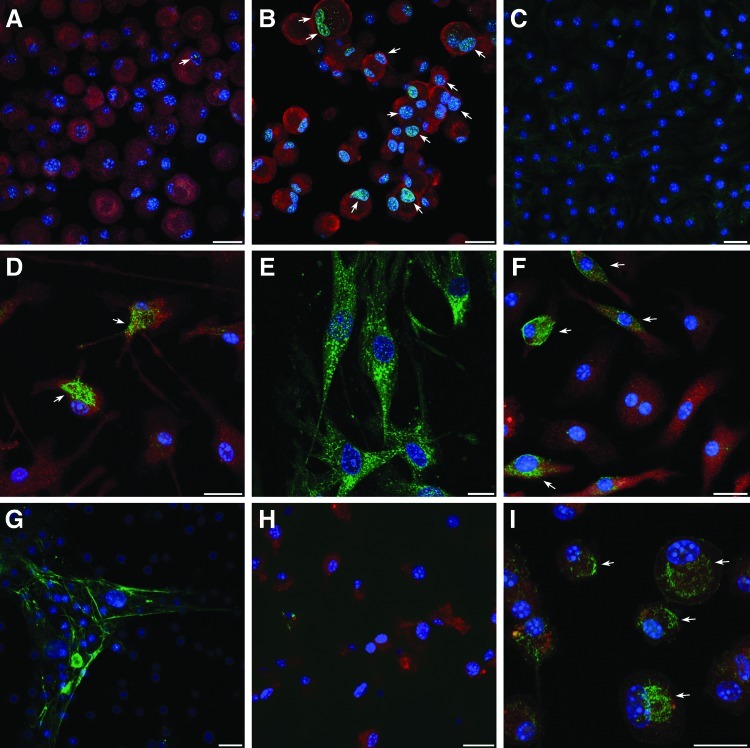

To confirm that the cardiac differentiation that was observed in response to the 2-step BIX01294/Wnt11 treatment was not limited to transcription only, we performed immunofluorescent analysis of myocardial protein expression within the BM cultures (Fig. 8). For example, GATA4 was barely present in nontreated and BIX01294-treated cells (Fig. 8A), but was readily observed in nuclei of cells treated with BIX01294 plus Wnt11 (Fig. 8B). Striated muscle proteins, such as titin (Fig. 8C–E) were also displayed in response to the BIX01294/Wnt11 2-step treatment, although the protein was not yet organized into cytoskeletal structures. Other muscle proteins detected in these cultures were sarcomeric α-actinin, SA-actin, and desmin (Fig. 8F–I). Each of these cytoskeletal molecules are among the first muscle proteins to be exhibited in newly differentiated cardiomyocytes in the embryonic heart [75,76]. As shown for titin (Fig. 8C) and sarcomeric α-actinin (Fig. 8C), none of these muscle proteins were exhibited in cultures that were not treated with BIX01294 plus Wnt11. In total, these data show that BIX01294 treatment of BM cells provokes a phenotypic change to a cardiac competent, mesodermal progenitor that can undergo cardiomyogenic differentiation in response to cardiac-inducing factors.

FIG. 8.

Immunofluorescent analysis of cardiac differentiation of BM-derived cells. Cardiac proteins were identified using protein-specific antibodies labeled with DyLight 488 (green). In addition, cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenyindole (DAPI, blue) and rhodamine-coupled wheat germ agglutinin (red), respectively, to identify nuclei and visualize individual cells. BM cells were exposed to BIX01294 for 48 h before their culture for 7 days in the (A) absence or (B) presence of Wnt11, and subsequently immunostained for GATA4. In the absence of Wnt11, very few cells were observed that exhibited positive staining for GATA4 (arrow). In contrast, Wnt11 provoked greater numbers of BIX01294-pretreated cells to exhibit GATA4 reactivity, as indicated by the green, yellow fluorescent dots within individual nuclei (arrows). BM cultures immunostained against titin after being cultured in the (C) absence or (D, E) presence of BIX01294, and then subsequently exposed to Wnt11 for 7 days. Both (F) sarcomeric α-actin and (H) desmin displayed positive immunofluorescent staining following the 2-step BIX01294/Wnt11 treatment. Sarcomeric α-actinin immunostained BM cells cultured with (H) Wnt11 only or (I) Wnt11 following pretreatment with BIX01294. Arrows in (D, F, I) identify individual cells that exhibit the myofibrillar proteins in a preorganized pattern within the cytoplasm. For (A, B, H, I), both the BIX01294-pretreatment and subsequent 7-day culture were carried out in the same dish, before cytospinning trypsinized cells onto glass slides for immunostaining. For (C–G), cells were harvested following the 48-h pretreatment and replated into chamber slides for subsequent Wnt11 culture and immunostaining. Scale bars=20 μm.

Discussion

The development of stem cell therapies for treating cardiovascular diseases has been a major goal of research scientists and clinicians [77,78]. While successful stem cell interventions have been obtained using animal models [17,79–81], as well as promising results in clinical trials on cardiac patients [82–84], the outcomes from these studies has not always been repeatable and has often been rather modest in effect [85,86]. It is not yet clear what the best sources are of stem cells for cardiac repair, and whether these various stem cell populations have been optimized in their cardiac capacity. Great hope has been placed on iPSCs because of their functional similarities to ES cells. However, iPSCs also suffer from the same drawbacks as ES cells, in having a differentiation potential that is difficult to control and the tendency to form tumors [8–10]. Endogenous cardiac progenitor cells exist in the adult heart, which contribute to new myocyte formation during normal homeostasis of the myocardium [87,88]. However, access to these cells requires a cardiac biopsy, and their subsequent expansion in culture to obtain sufficient numbers for repair of the diseased or damaged heart [89]. Other more accessible tissues, such as the BM or fat, contain stem cells that possess differentiation capacities that extend beyond their resident tissue [11–14]. Despite this, the capacity of these latter cells to form cardiomyocytes, although real, is low [15,18]. Unlike iPSCs and ES cells, BM-derived cells have not shown the capacity to form beating tissue and/or large numbers of differentiated cardiomyocytes in vitro that would allow these cells to serve as a source of engineered cardiac tissue.

Experiments described in this report were designed to explore ways to augment the cardiac potential of adult BM cells, thereby making them an efficient source of cardiac progenitor cells. In the effort to improve the cardiac competency of BM cells, we refrained from using genetic methods to change the cell phenotype and potential. Instead, we examined select pharmacological reagents and extracellular signaling proteins that have been shown to enhance the efficiency of iPSC production and/or maintain ES cell phenotype, but in themselves are insufficient to forge a pluripotent phenotype. Among reagents tested, the G9a HMTase inhibitor BIX01294 demonstrated the greatest potential as a promoter of a cardiocompetent phenotype, as it stimulated the expression of several genes (Mesp1, islet1, and brachyury) that define precardiac progenitors within the embryo. Of particular importance was the enhancement of Mesp1, whose expression identifies progenitors exhibiting myocardial competency in the early embryo [36–38]. In contrast, treatment of BM cells with BIX01294 produced minimal increases in transcription of pluripotency genes, and did not stimulate expression of early ectodermal and endodermal markers. That BM cells displayed an increased capacity to respond to stimuli that promote both cardiac and kidney gene expression suggests that BIX01294 has not provoked formation of a lineage-restricted cardiac progenitor cell, but has generated cells with the phenotypic potential of an early mesodermal progenitor. In resetting the BM cell phenotype, BIX01294 produced progenitor cells with an increased cardiac competency, which is realized when exposed to appropriate cardiogenic stimuli.

Along with the increase in precardiac markers in response to BIX01294, there was also a concomitant decrease in the hematopoietic progenitor cell marker GATA2. This outcome suggests a hypothesis that BIX01294 reversed the commitment of the mesoderm-derived BM progenitor cell from a hematopoietic fate to a cell with a broader pan-mesodermal cell potential. The respecification of BM progenitor cells by BIX01294 was revealed by an increased ability of these cells to differentiate when subsequently exposed to cardiomyogenic stimuli, as demonstrated by the upregulated transcription of Nkx2.5, GATA4, Hand1, Hand2, Tbx5, myocardin, and titin. The increased cardiac gene expression brought on by the treatments described in this study was reflected in the display of muscle protein expression, with pockets of cells exhibiting titin, sarcomeric α-actinin, SA-actin, and desmin—which are all among the first muscle proteins to be exhibited in the embryonic heart [75,76]. The lack of organization of the muscle proteins exhibited within the cultures indicates that the cells displaying cardiomyocyte proteins were only partially differentiated. The reasons for the less than complete cardiomyogenic differentiation may be due to a number of factors or causes. Neither Wnt11 nor other factors that are known to contribute to cardiomyocyte differentiation (e.g., BMP4, FGF2) have shown ability, either individually or in combination, to drive bona fide cardiac progenitors to form fully differentiated cardiomyocytes in culture [90,91]. Thus, it is not surprising that the reprogramming of noncardiomycyte progenitor cells to a phenotype resembling actual cardiocompetent cells would be unable to respond to cardiogenic stimuli in a manner that is beyond what has been observed for bona fide precardiac cells. In regard to the BIX01294 treatment itself, the targeting of G9a HMTase by itself may not be sufficient to fully convert progenitor cells that normally generate hematopoietic cells to a multipotent cardiocompetent cell, even though BIX01294 does appear to elicit the highest increased levels of precardiac and cardiomyocyte gene expression that have been reported. Other reagents have been described (such as 5-azacytidine, which targets DNA methylation) that have helped noncardiogenic cells exhibit cardiac-like properties [92,93]. Yet, due to the complexities of the signaling events involved, it is likely that no single drug will serve as a standalone reprogramming agent for making BM cells fully resemble endogenous cardiac progenitor cells. What this report does show is that BIX01294 may provide an important component of a multifactorial toolkit that would reprogram an accessible adult cell population into cells that could potentially be used for the therapeutic repair of the heart.

Successful reprogramming of somatic cells to cardiomyocytes has been described using an alternative method, where cardiac transcription factors were ectopically expressed by viral delivery [94]. While this latter approach offers considerable promise for cardiac therapy, dictation of phenotype using transgenes could lead to misregulated cardiac gene expression when the cells become integrated into the heart. Moreover, this transgenic transformation into a differentiated myocyte phenotype bypasses the cardiac progenitor stage, which comprises a cell population that may be more amenable for repair of certain types of cardiac anomalies and insults. By using external stimuli, as described in this study, to reset the cell phenotype to cardiac competent progenitors, the option would be available for repairing the heart by either direct administration of progenitor cells into the heart or prompting those cells to differentiate into cardiac cells in culture for engineering tissue grafts.

In summary, the data presented in this report illustrate the value of pharmacological reagents as tools for converting BM cells into cardiac-competent progenitors. Treatments with the G9a HMTase inhibitor, BIX01294, enhanced the cardiomyogenic potential of BM cells and demonstrated that this molecule has utility for deriving replacement cardiomyocytes from accessible adult cell sources.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH RO1HL073190 (L.M.E.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Takahashi K. Tanabe K. Ohnuki M. Narita M. Ichisaka T. Tomoda K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amabile G. Meissner A. Induced pluripotent stem cells: current progress and potential for regenerative medicine. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J. Wilson GF. Soerens AG. Koonce CH. Yu J. Palecek SP. Thomson JA. Kamp TJ. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2009;104:e30–e41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson TJ. Martinez-Fernandez A. Terzic A. Induced pluripotent stem cells: developmental biology to regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:700–710. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okita K. Hong H. Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells with plasmid vectors. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:418–428. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna JH. Saha K. Jaenisch R. Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming: facts, hypotheses, unresolved issues. Cell. 2010;143:508–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaehres H. Kim JB. Scholer HR. Induced pluripotent stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2010;476:309–325. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)76018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duinsbergen D. Salvatori D. Eriksson M. Mikkers H. Tumors originating from induced pluripotent stem cells and methods for their prevention. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1176:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong CY. Gauthaman K. Bongso A. Teratomas from pluripotent stem cells: A clinical hurdle. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:769–781. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wobus AM. The Janus face of pluripotent stem cells—connection between pluripotency and tumourigenicity. Bioessays. 2010;32:993–1002. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenberg LM. Eisenberg CA. Adult stem cells and their cardiac potential. Anat Rec. 2004;276A:103–112. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgkinson T. Yuan XF. Bayat A. Adult stem cells in tissue engineering. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6:621–640. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuci S. Kuci Z. Latifi-Pupovci H. Niethammer D. Handgretinger R. Schumm M. Bruchelt G. Bader P. Klingebiel T. Adult stem cells as an alternative source of multipotential (pluripotential) cells in regenerative medicine. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2009;4:107–117. doi: 10.2174/157488809788167427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rooney GE. Nistor GI. Barry FB. Keirstead HS. In vitro differentiation potential of human embryonic versus adult stem cells. Regen Med. 2010;5:365–379. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg CA. Burch JB. Eisenberg LM. Bone marrow cells transdifferentiate to cardiomyocytes when introduced into the embryonic heart. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1236–1245. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg LM. Burns L. Eisenberg CA. Hematopoietic cells from bone marrow have the potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro. Anat Rec. 2003;274A:870–882. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rota M. Kajstura J. Hosoda T. Bearzi C. Vitale S. Esposito G. Iaffaldano G. Padin-Iruegas ME. Gonzalez A, et al. Bone marrow cells adopt the cardiomyogenic fate in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17783–17788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706406104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez EC. Kofidis T. Adult stem cells for cardiac tissue engineering. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streckfuss-Bomeke K. Wolf F. Azizian A. Stauske M. Tiburcy M. Wagner S. Hubscher D. Dressel R. Chen S, et al. Comparative study of human-induced pluripotent stem cells derived from bone marrow cells, hair keratinocytes, and skin fibroblasts. Eur Heart J. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs203. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng Y. Wang Y. Cao N. Yang H. Progenitor/stem cell transplantation for repair of myocardial infarction: hype or hope? Ann Palliat Med. 2012;1:65–77. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2012.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang J. Han P. Zhang Q. Zhao J. Ma Y. Mercola M. Cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:1663–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying QL. Wray J. Nichols J. Batlle-Morera L. Doble B. Woodgett J. Cohen P. Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva J. Barrandon O. Nichols J. Kawaguchi J. Theunissen TW. Smith A. Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nusse R. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cell Res. 2008;18:523–527. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa K. Nishinakamura R. Iwamatsu Y. Shimosato D. Niwa H. Synergistic action of Wnt and LIF in maintaining pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichida JK. Blanchard J. Lam K. Son EY. Chung JE. Egli D. Loh KM. Carter AC. Di Giorgio FP, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of tgf-Beta signaling replaces sox2 in reprogramming by inducing nanog. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W. Wei W. Zhu S. Zhu J. Shi Y. Lin T. Hao E. Hayek A. Deng H. Ding S. Generation of rat and human induced pluripotent stem cells by combining genetic reprogramming and chemical inhibitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora-Castilla S. Tejedo JR. Hmadcha A. Cahuana GM. Martin F. Soria B. Bedoya FJ. Nitric oxide repression of Nanog promotes mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1025–1033. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huangfu D. Maehr R. Guo W. Eijkelenboom A. Snitow M. Chen AE. Melton DA. Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:795–797. doi: 10.1038/nbt1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desponts C. Ding S. Using small molecules to improve generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;636:207–218. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-691-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng B. Ng JH. Heng JC. Ng HH. Molecules that promote or enhance reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marson A. Foreman R. Chevalier B. Bilodeau S. Kahn M. Young RA. Jaenisch R. Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin BL. Kimelman D. Brachyury establishes the embryonic mesodermal progenitor niche. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2778–2783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1962910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inman KE. Downs KM. Localization of Brachyury (T) in embryonic and extraembryonic tissues during mouse gastrulation. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouskoff V. Lacaud G. Schwantz S. Fehling HJ. Keller G. Sequential development of hematopoietic and cardiac mesoderm during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13170–13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501672102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saga Y. Kitajima S. Miyagawa-Tomita S. Mesp1 expression is the earliest sign of cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu SM. Mesp1 at the heart of mesoderm lineage specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bondue A. Blanpain C. Mesp1: a key regulator of cardiovascular lineage commitment. Circ Res. 2010;107:1414–1427. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakano A. Nakano H. Chien KR. Multipotent islet-1 cardiovascular progenitors in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:297–306. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Genead R. Danielsson C. Andersson AB. Corbascio M. Franco-Cereceda A. Sylven C. Grinnemo KH. Islet-1 cells are cardiac progenitors present during the entire lifespan: from the embryonic stage to adulthood. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1601–1615. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brade T. Gessert S. Kuhl M. Pandur P. The amphibian second heart field: Xenopus islet-1 is required for cardiovascular development. Dev Biol. 2007;311:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma Q. Zhou B. Pu WT. Reassessment of Isl1 and Nkx2-5 cardiac fate maps using a Gata4-based reporter of Cre activity. Dev Biol. 2008;323:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allis CD. Berger SL. Cote J. Dent S. Jenuwien T. Kouzarides T. Pillus L. Reinberg D. Shi Y, et al. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell. 2007;131:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feldman N. Gerson A. Fang J. Li E. Zhang Y. Shinkai Y. Cedar H. Bergman Y. G9a-mediated irreversible epigenetic inactivation of Oct-3/4 during early embryogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:188–194. doi: 10.1038/ncb1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tachibana M. Ueda J. Fukuda M. Takeda N. Ohta T. Iwanari H. Sakihama T. Kodama T. Hamakubo T. Shinkai Y. Histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP form heteromeric complexes and are both crucial for methylation of euchromatin at H3-K9. Genes Dev. 2005;19:815–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golob JL. Paige SL. Muskheli V. Pabon L. Murry CE. Chromatin remodeling during mouse and human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1389–1398. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonasio R. Tu S. Reinberg D. Molecular signals of epigenetic states. Science. 2010;330:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1191078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi Y. Do JT. Desponts C. Hahm HS. Scholer HR. Ding S. A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gellibert F. Woolven J. Fouchet MH. Mathews N. Goodland H. Lovegrove V. Laroze A. Nguyen VL. Sautet S, et al. Identification of 1,5-naphthyridine derivatives as a novel series of potent and selective TGF-beta type I receptor inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4494–4506. doi: 10.1021/jm0400247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eisenberg CA. Eisenberg LM. WNT11 promotes cardiac tissue formation of early mesoderm. Dev Dyn. 1999;216:45–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199909)216:1<45::AID-DVDY7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wobus AM. Guan K. Pich U. In vitro differentiation of embryonic stem cells and analysis of cellular phenotypes. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;158:263–286. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-220-1:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisenberg CA. Bader DM. Establishment of the mesodermal cell line QCE-6. A model system for cardiac cell differentiation. Circ Res. 1996;78:205–216. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisenberg LM. Eisenberg CA. Evaluating the role of Wnt signal transduction in promoting the development of the heart. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:161–176. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sineva GS. Pospelov VA. Inhibition of GSK3beta enhances both adhesive and signalling activities of beta-catenin in mouse embryonic stem cells. Biol Cell. 2010;102:549–560. doi: 10.1042/BC20100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang AC. Fu Y. Garside VC. Niessen K. Chang L. Fuller M. Setiadi A. Smrz J. Kyle A, et al. Notch initiates the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the atrioventricular canal through autocrine activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Dev Cell. 2011;21:288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walther C. Gruss P. Pax-6, a murine paired box gene, is expressed in the developing CNS. Development. 1991;113:1435–1449. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bach A. Lallemand Y. Nicola MA. Ramos C. Mathis L. Maufras M. Robert B. Msx1 is required for dorsal diencephalon patterning. Development. 2003;130:4025–4036. doi: 10.1242/dev.00609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khadka D. Luo T. Sargent TD. Msx1 and Msx2 have shared essential functions in neural crest but may be dispensable in epidermis and axis formation in Xenopus. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:499–502. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052115dk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osumi N. Shinohara H. Numayama-Tsuruta K. Maekawa M. Concise review: Pax6 transcription factor contributes to both embryonic and adult neurogenesis as a multifunctional regulator. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1663–1672. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dziadek M. Adamson E. Localization and synthesis of alphafoetoprotein in post-implantation mouse embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1978;43:289–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burtscher I. Lickert H. Foxa2 regulates polarity and epithelialization in the endoderm germ layer of the mouse embryo. Development. 2009;136:1029–1038. doi: 10.1242/dev.028415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taube JH. Allton K. Duncan SA. Shen L. Barton MC. Foxa1 functions as a pioneer transcription factor at transposable elements to activate Afp during differentiation of embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16135–16144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Flaherty MP. Abdel-Latif A. Li Q. Hunt G. Ranjan S. Ou Q. Tang XL. Johnson RK. Bolli R. Dawn B. Noncanonical Wnt11 signaling is sufficient to induce cardiomyogenic differentiation in unfractionated bone marrow mononuclear cells. Circulation. 2008;117:2241–2252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagy II. Railo A. Rapila R. Hast T. Sormunen R. Tavi P. Rasanen J. Vainio SJ. Wnt-11 signalling controls ventricular myocardium development by patterning N-cadherin and beta-catenin expression. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:100–109. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eisenberg LM. Eisenberg CA. Wnt signal transduction and the formation of the myocardium. Dev Biol. 2006;293:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lako M. Strachan T. Bullen P. Wilson DI. Robson SC. Lindsay S. Isolation, characterisation and embryonic expression of WNT11, a gene which maps to 11q13.5 and has possible roles in the development of skeleton, kidney and lung. Gene. 1998;219:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Costa RH. Kalinichenko VV. Lim L. Transcription factors in mouse lung development and function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L823–L838. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weng T. Liu L. The role of pleiotrophin and beta-catenin in fetal lung development. Respir Res. 2010;11:80. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lou Y. Javed A. Hussain S. Colby J. Frederick D. Pratap J. Xie R. Gaur T. van Wijnen AJ, et al. A Runx2 threshold for the cleidocranial dysplasia phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:556–568. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Napierala D. Sam K. Morello R. Zheng Q. Munivez E. Shivdasani RA. Lee B. Uncoupling of chondrocyte differentiation and perichondrial mineralization underlies the skeletal dysplasia in tricho-rhino-phalangeal syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2244–2254. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mansouri A. Goudreau G. Gruss P. Pax genes and their role in organogenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1707s–1709s. discussion 1709s–1710s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Villanueva S. Cespedes C. Gonzalez A. Vio CP. bFGF induces an earlier expression of nephrogenic proteins after ischemic acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1677–R1687. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00023.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Falahatpisheh MH. Nanez A. Ramos KS. AHR regulates WT1 genetic programming during murine nephrogenesis. Mol Med. 2011;17:1275–1284. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou B. Ma Q. Rajagopal S. Wu SM. Domian I. Rivera-Feliciano J. Jiang D. von Gise A. Ikeda S. Chien KR. Pu WT. Epicardial progenitors contribute to the cardiomyocyte lineage in the developing heart. Nature. 2008;454:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eisenberg LM. Eisenberg CA. Onset of a cardiac phenotype in the early embryo. In: Dube DK, editor. Cardiovascular Molecular Morphogenesis: Myofibrillogenesis. Springer Verlag; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 181–205. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eisenberg LM. Moreno R. Markwald RR. Multiple stem cell populations contribute to the formation of the myocardium. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1047:38–49. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Segers VF. Lee RT. Stem-cell therapy for cardiac disease. Nature. 2008;451:937–942. doi: 10.1038/nature06800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Freund C. Mummery CL. Prospects for pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in cardiac cell therapy and as disease models. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:592–599. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Linke A. Muller P. Nurzynska D. Casarsa C. Torella D. Nascimbene A. Castaldo C. Cascapera S. Bohm M, et al. Stem cells in the dog heart are self-renewing, clonogenic, and multipotent and regenerate infarcted myocardium, improving cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8966–8971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502678102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rota M. Padin-Iruegas ME. Misao Y. De Angelis A. Maestroni S. Ferreira-Martins J. Fiumana E. Rastaldo R. Arcarese ML, et al. Local activation or implantation of cardiac progenitor cells rescues scarred infarcted myocardium improving cardiac function. Circ Res. 2008;103:107–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Laake LW. Passier R. Doevendans PA. Mummery CL. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and cardiac repair in rodents. Circ Res. 2008;102:1008–1010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fuh E. Brinton TJ. Bone marrow stem cells for the treatment of ischemic heart disease: a clinical trial review. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2009;2:202–218. doi: 10.1007/s12265-009-9095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kearns-Jonker M. Dai W. Kloner RA. Stem cells for the treatment of heart failure. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2010;12:432–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sanz-Ruiz R. Gutierrez Ibanes E. Arranz AV. Fernandez Santos ME. Fernandez PL. Fernandez-Aviles F. Phases I-III clinical trials using adult stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2010;2010:579142. doi: 10.4061/2010/579142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ballard VL. Stem cells for heart failure in the aging heart. Heart Fail Rev. 2010;15:447–456. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9160-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mummery CL. Davis RP. Krieger JE. Challenges in using stem cells for cardiac repair. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:27ps17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kajstura J. Gurusamy N. Ogorek B. Goichberg P. Clavo-Rondon C. Hosoda T. D'Amario D. Bardelli S. Beltrami AP, et al. Myocyte turnover in the aging human heart. Circ Res. 2010;107:1374–1386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kajstura J. Urbanek K. Perl S. Hosoda T. Zheng H. Ogorek B. Ferreira-Martins J. Goichberg P. Rondon-Clavo C, et al. Cardiomyogenesis in the adult human heart. Circ Res. 2010;107:305–315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 89.Davis DR. Kizana E. Terrovitis J. Barth AS. Zhang Y. Smith RR. Miake J. Marban E. Isolation and expansion of functionally-competent cardiac progenitor cells directly from heart biopsies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Willems E. Spiering S. Davidovics H. Lanier M. Xia Z. Dawson M. Cashman J. Mercola M. Small-molecule inhibitors of the Wnt pathway potently promote cardiomyocytes from human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm. Circ Res. 2011;109:360–364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang L. Soonpaa MH. Adler ED. Roepke TK. Kattman SJ. Kennedy M. Henckaerts E. Bonham K. Abbott GW, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Makino S. Fukuda K. Miyoshi S. Konishi F. Kodama H. Pan J. Sano M. Takahashi T. Hori S, et al. Cardiomyocytes can be generated from marrow stromal cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:697–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rajasingh J. Thangavel J. Siddiqui MR. Gomes I. Gao XP. Kishore R. Malik AB. Improvement of cardiac function in mouse myocardial infarction after transplantation of epigenetically-modified bone marrow progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ieda M. Fu JD. Delgado-Olguin P. Vedantham V. Hayashi Y. Bruneau BG. Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]