Abstract

Sulforaphane (SFN), an isothiocyanate found in cruciferous vegetables, is a potent inhibitor of experimental mammary carcinogenesis and may be an effective, safe chemopreventive agent for use in humans. SFN acts in part on the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway to regulate a battery of cytoprotective genes. In this study transcriptomic and proteomic changes in the estrogen receptor negative, non tumorigenic human breast epithelial MCF10A cell line were analyzed following SFN treatment or KEAP1 knockdown with siRNA using microarray and stable isotopic labeling with amino acids in culture (SILAC), respectively. Changes in selected transcripts and proteins were confirmed by PCR and Western blot in MCF10A and MCF12A cells. There was strong correlation between the transcriptomic and proteomic responses in both the SFN treatment (R=0.679, P<0.05) and KEAP1 knockdown (R=0.853, P<0.05) experiments. Common pathways for SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown were xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidants, glutathione metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism and NADH/NADPH regeneration. Moreover, these pathways were most prominent in both the transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. The aldo-keto reductase family members, AKR1B10, AKR1C1, AKR1C2 and AKR1C3, as well as NQO1 and ALDH3A1, were highly upregulated at both the transcriptomic and proteomic level. Collectively, these studies served to identify potential biomarkers that can be used in clinical trials to investigate the initial pharmacodynamic action of SFN in the breast.

Keywords: sulforaphane, prevention, Keap1/Nrf2 pathway, biomarker discovery, microarray, SILAC

Introduction

Breast cancer remains a significant worldwide public health concern despite advances in early detection and treatment. In the United States breast cancer is currently the greatest contributor to cancer incidence and the second cause of cancer mortality in women [1]. Combating this disease before it ensues can reduce incidence and deaths considerably. The selective estrogen receptor (ER) modulators, tamoxifen and raloxifene, are the only United States Food and Drug Administration approved chemoprevention drugs for women with elevated breast cancer risk. The perception of adverse side effects with these drugs [2] coupled with lack of well developed chemopreventive options for the often more aggressive ER negative cancers, call for new molecular targets for breast cancer prevention.

A potential chemopreventive agent is sulforaphane (SFN), an isothiocyanate found in cruciferous vegetables with particularly high levels in 3-day old broccoli sprouts [3]. It is converted by hydrolysis of the glucosinolate, glucoraphanin, by the enzyme myrosinase. SFN is an attractive chemopreventive agent because it is safe and can be distributed widely as broccoli sprout extract (BSE) preparations [4,5]. The best characterized mechanism through which SFN protects cells from endogenous and exogenous carcinogenic damage [6] is by induction of detoxication and antioxidant enzymes such as NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1), the aldo-keto reductase (AKR) family of enzymes, and heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) [7–10]. Enzyme transcripts are induced when the Nuclear factor-E2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) transcription factor binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) at the regulatory regions of these genes [11]. Nrf2 is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm by an inhibitory interaction with Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1 (Keap1). SFN interacts with critical cysteines in Keap1, thereby disrupting Keap1 facilitated ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 [12] and allowing Nrf2 to translocate into the nucleus and modulate expression of its target genes. Other potential mechanisms of SFN action include antiproliferative effects, NF-κB DNA binding inhibition, apoptosis activation and histone deacetylase inhibition [13,14]. Based on its varied molecular targets, SFN has the potential to prevent breast cancer irrespective of ER status.

When 3-day old BSE as given to female rats treated with 7–12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene, the number, size and rate of mammary tumor development were significantly reduced [3,15]. Upregulation of Nqo1 and Hmox1 transcripts, as well as NQO1 activity and HMOX1 protein levels was observed in rat mammary glands after SFN treatment [16]. Transcriptomic and proteomic studies analyzing SFN regulation have focused on rodent cells [8,17,9,18–21] and human cancer cells [22–26]. However, the effects of SFN on non-cancerous human cells are not known.

Standardized BSE preparations with defined concentrations of SFN and glucoraphanin have been developed and the metabolism and elimination pharmacokinetics of SFN have been measured [4,27,28]. However there is a need for biomarkers that effectively define the pharmacodynamic action of SFN in human tissues. In this preclinical study we treated the human ER negative [29] non tumorigenic [30] MCF10A cell line with SFN in order to analyze global transcript and protein expression changes using microarray and SILAC technologies, respectively. To affirm the role of Nrf2 signaling in the pharmacodynamic action of SFN in non cancerous human cells, siRNA against KEAP1 was utilized to provide a parallel genetic mechanism to increase Nrf2 signaling. Several genes and proteins with low constitutive expression, but with a broad dynamic range of induction following pharmacologic or genetic stimulation, were identified. Such properties define potentially useful biomarkers for evaluating the mechanism of action and optimizing the dose and schedule of broccoli sprout preparations in clinical trials, especially those targeting the breast.

Material and Methods

Chemicals

R,S-Sulforaphane was purchased from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN). Acetonitrile (ACN) was from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH).

Cell Culture

MCF10A and MCF12A (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) cells were cultured in (DMEM)/F12 minus L-lysine and L-arginine for SILAC. Medium was supplemented with 5% horse serum, 20ng/ml epidermal Growth Factor, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin and 10 μg/ml insulin at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2. For light medium 12C6 L-lysine:2HCL and 12C6 L-arginine-HCl were supplemented and for heavy medium 13C6 L-lysine:2HCl and 13C6 L-arginine:HCl were added (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). Cells were transfected with 30nM KEAP1 or non targeting control (NTC) siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) in heavy and light media respectively according to the Lipofectamine™ RNAiMax reagent (Invitrogen) reverse transfection protocol. Cells were treated with 15 μM SFN or ACN vehicle in heavy and light medium respectively 24 hours after plating. RNA was collected 24 hours and protein collected 48 post transfection and SFN treatment (Figure 1 and 2).

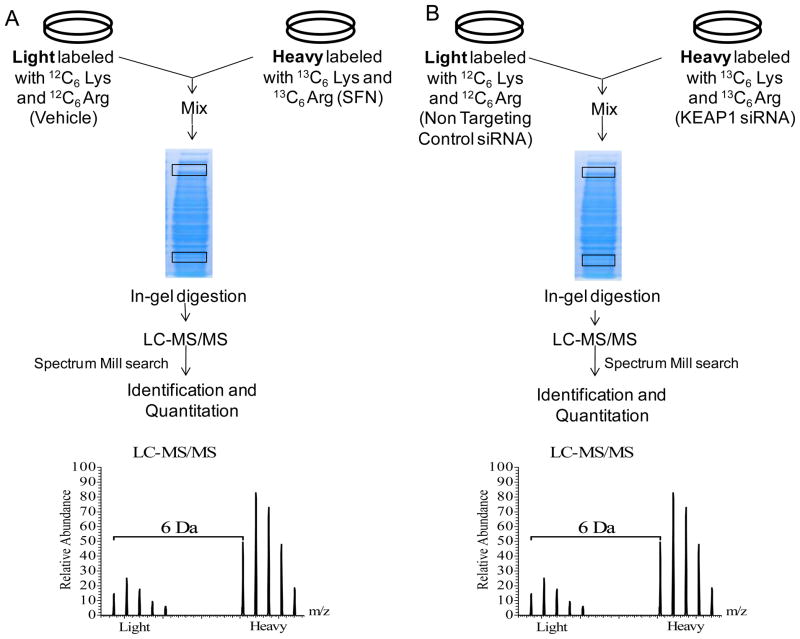

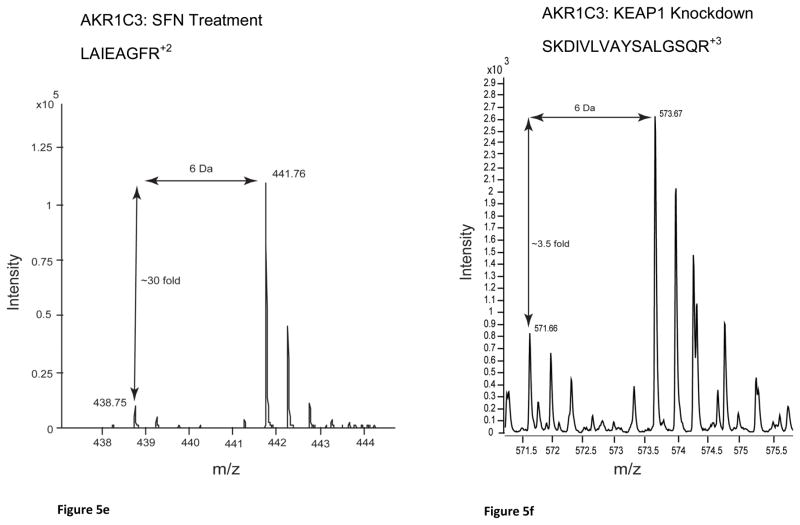

Figure 1.

Workflow for microarray and SILAC experiments. The vehicle used for SFN was acetonitrile. NTC=Non Targeting Control. LC-MS/MS = Liquid Chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. QTOF = Quadripole Time of Flight

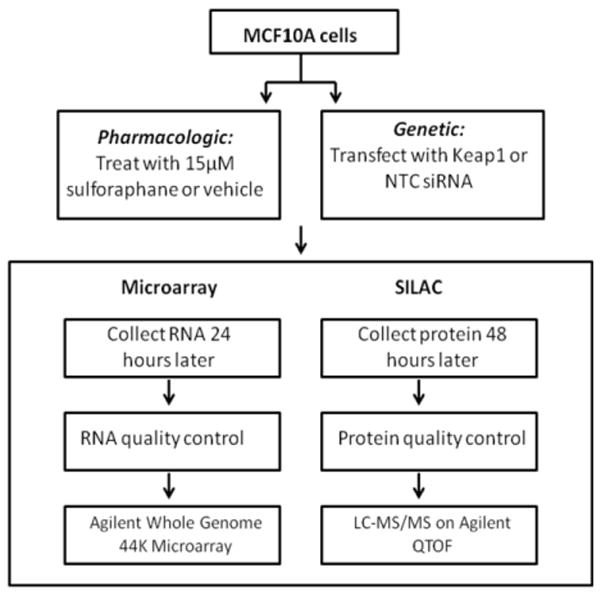

Figure 2.

Detailed workflow for SILAC experiments. The vehicle used for SFN was acetonitrile. Lys=Lysine. Arg=Arginine. Prototypical MS traces from LC-MS/MS are shown indicating the 6 Dalton (Da) shift between light and heavy labeled amino acid isotopes.

Microarray

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIZol reagent, and purified by the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit. RNA quality assessment was carried out according to previously published methods [31]. Agilent whole human genome chips (G4112F), with 41,000 unique probes, representing 26,705 genes, were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown experiments each had four biological replicates. Data was imported into GeneSpring GX 11.5 (Agilent Technologies) and differentially expressed genes were identified by unpaired t-test with a cut-off p<0.05. Correction for false discovery rate (FDR) of 5% was made using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure and a 1.5 fold change cut-off was implemented. The microarray data set has been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus. Agilent probe identification numbers and corresponding fold change values were exported to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software (Ingenuity® Systems, Redwood City, CA).

Quantiative Real time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

The qScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithesburg, MD) was used to convert 1 μg RNA to 50 ng/μl cDNA. TaqMan Gene Expression Assays and Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were then used to amplify 10 ng/μl cDNA with TBP as the endogenous control. Fold-change values were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt relative quantification method [32]

SILAC

Protein was extracted in 8 M Urea (Thermo Scientific) and the in-gel trypsin digestion method for SILAC was followed according to previously published protocols [33]. Peptides were analyzed using the Agilent 6538-accurate-mass QTOF mass spectrometer. A technical replicate was run under the same conditions. The MS data were searched and quantified at an FDR of 1% using Spectrum Mill MS Proteomics Workbench (Agilent, Rev A.03.03) using the Human RefSeq 35 protein sequence database (34, 906 sequences). Proteins with a single unique peptide identification from Spectrum Mill were confirmed by manual inspection of MS/MS spectra. The complete set of raw data (.raw files) generated from this study has been made available through the Tranche server stable URL https://proteomecommons.org/tranche/data. The protein accession numbers and their corresponding protein fold changes were exported to IPA.

Immunoblot analysis

Protein lysates were resolved on 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked in Odyssey® blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Linocln, Nebraska), and then incubated with the following primary antibodies: 1:750 mouse anti-NQO1, 1:1500 rabbit anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA); 1:750 mouse anti-AKRIC1, 1:1000 l rabbit anti-AKRIC3, 1:750 mouse anti-AKRB10, 1:500 mouse anti-GCLC, 1:2000 rabbit anti-BACTIN (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); 1:1000 rabbit anti-ALDH3A1 and 1:750 rabbit anti-KEAP1 (Proteintech group, Chicago, IL); 1:1250 mouse anti-SQSTM1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The blots were then incubated with IRDye® fluorescent secondary antibodies and scanned with the Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). The infrared fluorescence densitometry ratios for treated samples compared to controls were determined for three biological replicates and normalization was to GAPDH or BACTIN.

Results

MCF10A cells were treated with SFN or KEAP1 siRNA to provide pharmacologic and genetic means to alter Nrf2 signaling; global gene and protein expression were then analyzed by microarray and SILAC, respectively (Figure 1 and 2). KEAP1 transcripts were knocked down by 81% in the MCF10A cells (Online Resource (OR) 1-Table 3) while KEAP1 protein levels decreased 79% (Figure 4, OR1-Table 4). For the microarray analyses there were 6378 transcripts significantly regulated by SFN above and below the chosen 1.5 fold change cut off and 1710 transcripts significantly regulated by KEAP1 knockdown. The overlap between these two experiments was 879 transcripts. The main focus for the microarray pathway analyses were those transcripts shown to be regulated by both SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown. The top pathways to emerge for this subset of genes were xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidants, glutathione metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism and NADH/NADPH regeneration.

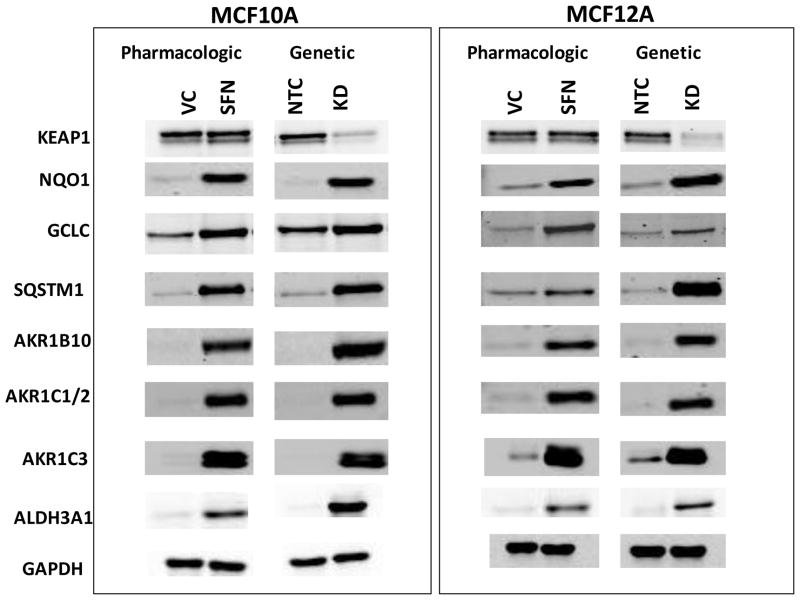

Figure 4.

Western blots for proteins of interest from microarray and SILAC studies showing elevation of protein levels with SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown.

The SILAC analysis indicated a normal distribution with the majority of proteins minimally regulated and a small percentage of proteins upregulated and downregulated above and below a 1.5 fold change cut-off (Figure 3). With SFN treatment, of the 666 proteins that were detected by the mass spectrometer, 96 proteins were upregulated and 26 were downregulated above and below a 1.5 fold change cut-off, respectively. For KEAP1 knockdown, of the 1,102 proteins that were detected, 50 were upregulated and 76 were downregulated. The overlap for these two experiments, within the 1.5 fold change cut-off, was 29 proteins. Pathway analysis of the genetic and pharmacologic SILAC experiments yielded xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidants, glutathione metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism and NADH/NADPH regeneration as top regulated pathways, in agreement with the microarray analysis. The members of the top gene and protein IPA based functional groups are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Right: Distribution of fold changes in proteins determined by SILAC between vehicle and SFN treated MCF-10A cells. Highlighted are the 96 upregulated and 26 downregulated proteins above and below a 1.5 fold change cut-off respectively. VC= Vehicle Control

Left: Distribution of fold changes in proteins determined by SILAC between Non targeting Control and KEAP1 knockdown siRNA treated MCF-10A cells. Highlighted are the 50 upregulated and 76 downregulated proteins above and below a 1.5 fold change cut-off respectively. NTC=Non Targeting Control. KEAP1 KD= KEAP1 knockdown.

Table 1.

Functional Groups for Transcriptomic and Proteomic Experiments

| Gene Symbol | Description | SFN Fold Change | KEAP1 Knock down fold change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Microarray | SILAC | Microarray | SILAC | ||

|

| |||||

| Xenobiotic Metabolism and Antioxidants | |||||

| AKR1B1 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member B1 | 3.4 | -- | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| AKR1B10 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member B10 | 302.9 | -- | 69.4 | -- |

| AKR1C1/2 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C1/2 | 14.8 | 30.7 | 34.7 | 9.2 |

| AKR1C3 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C3 | 27.0 | 39.3 | 16.0 | 4.8 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase | 4.4 | 3.7 | 6.7 | 4.4 |

| ALDH3A1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member A1 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 26.3 | 5.4 |

| ALDH3A2 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member A2 | - | -- | 1.9 | -- |

| ALDH1B1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member B1 | −1.7 | -- | −2.1 | −1.5 |

| TXNRD1 | thioredoxin reductase 1, | 10.2 | -- | 7.3 | 2.8 |

| TXN | thioredoxin | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| TXNDC13 | thioredoxin domain-containing protein 13 precursor | −1.6 | -- | 1.5 | -- |

| TMX1 | thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 1 precursor | - | 2.2 | - | -- |

| PRDX1 | peroxiredoxin 1 | 1.6 | -- | 1.5 | -- |

| EPHX1 | epoxide hydrolase 1, microsomal (xenobiotic) | 4.0 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.7 |

| HMOX1 | heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 9.6 | -- | 2.5 | -- |

| SULT1A1 | sulfotransferase family, cytosolic, 1A, phenol-preferring, member 1 | 1.7 | -- | 1.5 | -- |

| SULT1A2 | sulfotransferase family, cytosolic, 1A, phenol-preferring, member 2 | 4.4 | -- | 2.3 | -- |

| SRXN1 | sulfiredoxin 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 6.0 | -- | 4.0 | -- |

| LTB4DH | leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase | 10.8 | -- | 3.9 | -- |

| GPX2 | glutathione peroxidase 2 (gastrointestinal) | 2.7 | -- | 9.1 | -- |

| GPX8 | glutathione peroxidase 8 | −1.7 | -- | −2.6 | -- |

| MGST1 | microsomal glutathione S-transferase 1 | 1.5 | -- | 1.7 | - |

| GSTM1 | glutathione S-transferase M1 | 1.7 | -- | 1.9 | -- |

| GSTM4 | glutathione S-transferase M4 | 1.6 | -- | 1.7 | -- |

| BLVRB | biliverdin reductase B (flavin reductase (NADPH)) | 3.3 | -- | 1.5 | -- |

| BLVRA | biliverdin reductase A | 1.5 | 4.6 | - | -- |

| UGT1A6 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide A6, | 26.5 | -- | 13.0 | -- |

| CBR1 | carbonyl reductase 1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | -- |

| CBR3 | carbonyl reductase 3 | 1.9 | -- | 4.1 | -- |

| DNAJB4 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 4 | 5.4 | -- | 2.7 | -- |

| DNAJB9 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 9 | 2.1 | -- | 1.5 | -- |

| FTH1 | ferritin, heavy polypeptide 1 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 | -- |

| FTHL12 | ferritin, heavy polypeptide-like 12 | 2.9 | -- | 2.5 | -- |

| FTHL17 | ferritin, heavy polypeptide-like 17 | 2.7 | -- | 2.0 | -- |

| FTL | ferritin, light polypeptide | 13.8 | -- | 5.4 | -- |

| UBE2H | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (UBC8 homolog, yeast) | 2.3 | -- | 1.7 | -- |

| UBE2S | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2S | −1.6 | -- | - | -- |

| UBE2K | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2K (UBC1 homolog, yeast)1 | −2.1 | -- | −2.4 | -- |

| HSPB8 | heat shock 22kDa protein 8 | 8.2 | -- | 2.1 | -- |

| HSPA1A | heat shock 70kDa protein 1A | 1.8 | -- | −1.9 | -- |

| HSPC105 | NAD(P) dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like | 1.5 | -- | 1.9 | -- |

| AHSA1 | activator of 90 kDa heat shock protein ATPase homolog 1 | - | 2.5 | - | -- |

| ABCC2 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 2 | 5.3 | -- | 4.0 | -- |

| AOX1 | aldehyde oxidase 1 | 3.7 | -- | −2.2 | -- |

|

| |||||

| Glutathione metabolism | |||||

| GCLC | glutamate-cysteine ligase, catlytic subunit | 4.5 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.4 |

| GCLM | glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 2.4 |

| GSR | glutathione reductase | 2.9 | 1.7 | 2.2 | -- |

| GLRX | glutaredoxin 1 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 2.0 | -- |

| GLS | glutaminase | 2.7 | -- | 1.7 | -- |

| GGT1 | gamma-glutamyltransferase 1 | 1.7 | -- | 2.2 | -- |

| GGTLA4 | gamma-glutamyltransferase-like activity 4 | 1.8 | -- | 2.5 | -- |

|

| |||||

| Carbohydrate metabolism and NAD (P)H generation | |||||

| PGD | phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| G6PD | glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.7 |

| UGDH | UDP-glucose dehydrogenase | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| TALDO1 | transaldolase | 1.5 | -- | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| TKT | transketolase isoform 1 | - | 1.5 | - | 1.5 |

| HDK1 | hexokinase domain containing 1 | 146.9 | -- | 29.6 | -- |

| HK1 | hexokinase-1 isoform HKI-ta/tb | - | 1.5 | - | -- |

| PGAM1 | phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | −1.6 | 1.6 | - | -- |

| NDUFA4 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 4 | - | 1.5 | - | -- |

| COX2 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit II | - | -- | - | −1.5 |

| COX4I1 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1 precursor | - | -- | - | −1.5 |

Microarray and SILAC results for SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown in MCF10A cells. Transcripts that were either not significantly altered in the microarray or were not regulated above or below the 1.5 fold change cut off are denoted by a dash (-). For the SILAC results proteins that were not detected by the mass spectrometer, were not statistically significant or were not regulated above or below the 1.5 fold change cut off are denoted by a double dash (--)

The Xenobiotic and Antioxidant Transcripts and Proteins were the Predominant Group Regulated by SFN Treatment and KEAP1Knockdown

Key genes and proteins involved in xenobiotic metabolism were regulated by SFN treatment and/or KEAP1 knockdown in both microarray and SILAC experiments included AKR1 subfamily members, NQO1, CBR1, ALDH3A1 and EPHX1 (Table 1). The antioxidant genes TXNRD1, FTH, BLVRA and TXN were also coordinately regulated. The genes NQO1, AKR1B10, AKR1C1, AKR1C2, HMOX1, GPX2, TXNRD1, TXN, FTH, FTL, GSR, and PRDX1, have been shown to have AREs [34–37]. Strikingly, the most highly upregulated transcripts and proteins were the AKR1 subfamily members. AKR1B10 was the most highly upregulated transcript with 302.9 and 69.4 fold increases by SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown respectively (Table 1). While AKR1B10 was not observed by SILAC, Western blot analysis showed that this protein was dramatically upregulated by SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown (Figure 4). AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 also had high transcript levels compared to the other xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidant genes. AKR1C3 was one of the most highly upregulated proteins in the SFN treatment SILAC experiment at 39.3 fold, and was upregulated by 4.8 fold in the KEAP1 knockdown SILAC experiment. The AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 family members were collectively referred to as AKR1C1/2 because the mass spectrometry and immunoblot techniques were not able to differentiate conclusively between them (OR1- Figure 1). AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 differ by only 7 amino acids [38]. The differences in nucleotide sequence enabled the design of specific primer probes used to detect AKR1C1 for the qRT-PCR experiment (OR1-Table 3). AKR1C1/2 was highly upregulated in the SFN treatment SILAC experiment but less so in the KEAP1 knockdown SILAC (Table 1). AKR1B1 was upregulated to lower levels compared to the other AKR1 subfamily members in both the microarray and SILAC experiments.

Of the 43 transcripts regulated in this class, 14 were correspondingly altered by SFN treatment and/or KEAP1 knockdown using SILAC (Table 1, OR1-Table 1 and 2). The transcript and protein levels correlated well in terms of the direction of the fold change. This was clearly seen with the AKR1 subfamily members, NQO1, TXN, CBR1, ALDH1B1 and FTH1 for which the direction and magnitude of the fold change were well correlated. For AKR1C1, ALDH3A1, EPHX1 and BLVRA, although the magnitude of the fold changes for the microarray and SILAC were not strongly correlated, they were upregulated in all cases. There were few downregulated transcripts and in one case, ALDH1B1, both transcript and protein decreased. In addition to the AKR1 subfamily other families that were coordinately regulated by SFN treatment and/or KEAP1 knockdown included the ALDH, GST, FTH, UBE, HSP and TXN families. Some transcripts and proteins that modulate the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway were regulated by SFN treatment or KEAP1 knockdown as well. MAFG transcript levels were upregulated by 2.3 and 2.9 fold in the SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown experiments, respectively (OR1-Table 3). SQSTM1 was upregulated by 6.1 fold and 2.1 fold by SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown, respectively (OR1-Table 1 and 2) in the microarray. SQSTM1 was also upregulated by 4.3 fold with KEAP1 knockdown in the SILAC and was shown to be upregulated by SFN treatment by Western blot analysis (Figure 4).

Expression of Glutathione and Carbohydrate Metabolism Transcripts and Protein

Half of the transcripts associated with gluthathione metabolism were also upregulated at the protein level. GSR, GCLC and GCLM promoter regions have been shown to contain functional AREs [36]. These genes were also regulated at the protein level, with GCLC and GCLM upregulated by both SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown and GSR regulated by SFN treatment only. GCLC and GCLM transcripts and protein were upregulated to similar levels as seen with previous studies [10,39]. GLRX was the only other transcript that was upregulated at the protein level, and it is only regulated by SFN treatment.

Carbohydrate metabolism and NADH/NADPH regeneration are key functions that can be regulated by the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway by genetic and pharmacologic intervention. G6PD, PGD and UGDH are typically observed in microarray analyses following activation of the Nrf2 pathway [10,40,39,8,22]. In our study these enzymes exhibited correlated changes in transcript and protein levels in terms of both direction and magnitude. Within the carbohydrate metabolism and NADH/NADPH regeneration classes different aspects of carbohydrate metabolism were represented. G6PD, PGD, TALDO1 and TKT are key enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway, while PGAM1, HK1 and HDK1 are involved in glycolysis. HKD1 is the second most highly upregulated transcript in the microarray with a fold change of 146.9 with SFN treatment. Unlike the most highly upregulated transcript AKR1B10, HKD1 did not show elevated protein level in the SILAC. The mitochondrial electron transport chain proteins NDUFA4, COX2 and COX4I1 were regulated exclusively in the SILAC experiments.

Correlation between Microarray and SILAC Responses

A Spearman rank order correlation analysis between the microarray and SILAC results indicated a strong correlation for the SFN treatment (R=0.679, P<0.05) and KEAP1 knockdown (R=0.853, P<0.05) experiments in those instances where ≥ 1.5 fold changes were observed. A selected number of genes were validated by qRT-PCR in both MCF10A and MCF12A cells, a second non malignant human breast epithelial cell line (OR1-Table 3). There was good correlation in the MCF10A cells between the SFN treatment and KEAP1 knockdown microarray experiments (R=0.734, P<0.0001). There was also very good correlation between MCF10A microarray and qRTPCR data for SFN treatment (R=0.953, P<0.0001) and KEAP1 knockdown (R=0.977 P<0.0001). MCF10A microarray and MCF12A qRTPCR were also well correlated for SFN treatment (R=0.762, P<0.0001) and KEAP1 knockdown (R=0.782, P<0.0001). Lastly the qRT-PCR data for MCF10A and MCF12A correlated well for SFN treatment (R=0.821, P<0.0001) and KEAP1 knockdown (R=0.798, P<0.0001).

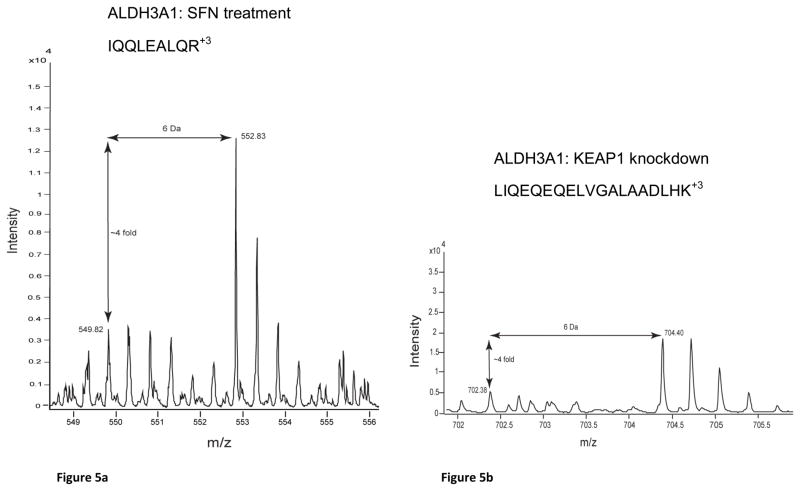

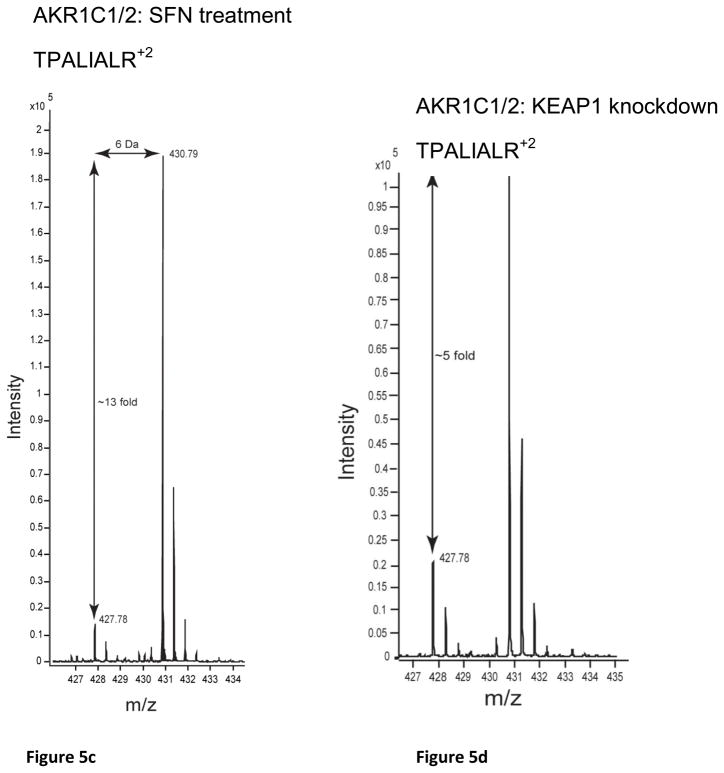

Correlation between Western blot and MS spectra

Western blots of MCF10A and MCF12As reproduced the protein fold changes observed in SILAC experiments. The proteins, NQO1, AKR1C1/2, AKR1C3, AKR1B10, SQSTM1, GCLC and ALDH3A1, were all shown to be upregulated, as seen by SILAC, whereas KEAP1 was shown to be downregulated (Figure 4, OR1-Table 4). The MS spectra for four proteins of interest, ALDH3A1, AKR1C1/2, AKR1C3, and NQO1, are shown in Figure 5 and the SILAC fold changes are represented with arrows. ALDH3A1 and SQSTM1 were not detected in the SFN treatment SILAC and AKR1B10 was not detected in either SILAC experiment at a FDR of 1%, however they were all shown to be upregulated by Western blot (Figure 4). The MS spectra for these proteins at a FDR of 5% were searched for and corresponding peaks for ALDH3A1 (Figure 5a) were found but SQSTM1 and AKR1B10 were not.

Figure 5.

MS spectra from SILAC analyses of candidate biomarker proteins: (a) ALDH3A1:SFN Treatment, (b) ALDH3A1:KEAP1 Knockdown, (c) AKR1C1/2: SFN Treatment, (d) AKR1C1/2: KEAP1 Knockdown, (e) AKR1C3: SFN Treatment, (f) AKR1C3: KEAP1 knockdown, (g) NQO1: SFN Treatment and (h) NQO1: KEAP1 Knockdown

Discussion

Although several clinical trials evaluating SFN are in progress, there has been little characterization of its pharmacodynamic action in humans. Few studies have looked at KEAP1/NRF2 mediated gene regulation in normal human cells using the strategy of knocking down KEAP1 [41,10]. In one of the two published studies using this approach, MacLeod et al [10] employed microarray analysis in human keratinocytes after KEAP1 knockdown and SFN treatment. Many of the genes that were regulated in their study were also regulated in ours study including AKR1B1, AKR1B10, AKR1C1/2, AKR1C3, NQO1, LTB4DH, GCLC, GCLM, GSR, G6PD PGD, HMOX1, SRXN1, TXNRD1, FTL, FTH and MAFG. These transcripts have also been shown to be upregulated in other microarray experiments using pharmacologic and/or genetic regulation of the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway in rodent tissues [8,10,22,40,39]. Whereas microarray analyses are common, quantitative proteomic experiments have not, to our knowledge, been used as an unbiased approach to study the proteins regulated by SFN treatment or in response to KEAP1 knockdown in non cancerous human cells. There is one report of an unbiased proteomic study with isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) analyzing KEAP1/NRF2 pathway regulation in rodent cells [21]. Two proteome-based studies of SFN action have focused on cancer cell lines [25,26]. We chose the SILAC strategy for our quantitative proteomic experiment because it allowed comprehensive in vivo labeling of the proteome of cultured cells that could couple global protein expression with a transcriptomic analysis [33]. A straightforward and efficient labeling process allows SILAC experiments to be highly reproducible. Another major benefit of SLAC is virtually no physico-chemical difference between the labeled and natural amino acid isotope, allowing the labeled cells to function identically to the control cells. Apart from LTB4DH, HMOX1, SRXN1 and MAFG, all the transcripts commonly regulated in our study and the Macleod study [10] were also upregulated in this SILAC experiment. IPA analysis showed that familiar cytoprotective pathways were regulated in both the transcriptomic and proteomic data sets further highlighting the fact that well known KEAP1/NRF2 modulated genes were regulated at both levels. This result provided internal validation for our approach. Another form of validation was the observed upregulation of MAFG transcripts and SQSTM1 transcripts and proteins, which serve to positively modulate NRF2 signaling. Small Maf proteins are required for the upregulation of cytoprotective transcripts [11]. The SQSTM1 gene has a functional ARE and positively modulates the KEAP/NRF2 pathway [42]. ALDH1 activity is a marker of stem cells in normal and malignant human mammary cells [43]. ALDH1B1, has recently been associated with stem cells in normal and cancerous colon tissue [44]. It was downregulated at the transcript level and by Keap1 knockdown at the protein level in our study. SFN has previously been shown to downregulate ALDH positive breast cancer stem cells [45]. ALDH3A1 and A2 which are cytoprotective in normal tissues were upregulated in our studies. The carbohydrate metabolism gene and protein expression correlated very well. NADH is produced from glycolysis and is an essential cofactor for many of the enzymes in the xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidant class. The electrons carried by NADH are fed into the mitochondrial electron transport chain to ultimately produce ATP. The mitochondrial electron transport chain proteins NDUFA4, COX2 and COX4I1 were regulated exclusively at the protein level in our study. NADPH is produced from the pentose phosphate pathway and is also an important coenzyme for xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidant enzymes. NADPH is required for the regeneration of reduced glutathione, GSH, by GSR.

For the microarray the overlap between the pharmacologic and genetic experiments was 51% of all the genes regulated by KEAP1 knockdown but only 14 % of the genes regulated by SFN treatment. These results indicate that many SFN regulated transcripts were not regulated through the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway. These is expected since SFN has been shown to affect a number of pathways beyond KEAP1/NRF2 [13]. The number of proteins detected by mass spectrometry in the SILAC experiments was strikingly lower than the number of transcripts differentially regulated in the microarray experiment by SFN. Some proteins may have undergone post translational modifications leading to diminished identification of proteins. It is most likely that many of the transcripts regulated by SFN treatment were translated to low abundance proteins not detected by mass spectrometery. Incomplete recovery of proteins from all cell compartments is an additional concern.

The AKR1 subfamily were the most highly upregulated family of genes and proteins. In a small clinical trial subjects received a glucosinolate-rich broccoli soup had high levels of AKRC1 and AKR1C2 in their gut mucosa [46]. In this study as well as other preclinical studies [10,47], or KEAP1 disruption [41,10] in cell lines, members of the AKR family were notably highly induced and suggested to be good biomarker candidates. Our studies confirmed that AKR1B1, AKR1B10, AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 were upregulated by the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway at both the transcript and protein level. Based on their dynamic upregulation and low basal expression AKR1 family members are potential biomarkers for SFN action in normal breast epithelial cells. AKR1B10 and AKR1B1 are aldose reductases enzymes that generally reduce carbonyls, including cytotoxic α-β-unsaturated carbonyls, to alcohols using NADPH as a cofactor [48]. Members of the AKR1C subfamily of enzymes are hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (HSD) and have the ability to reduce steroids [49]. AKR1C1and C2 reduce progesterone to weak androgens that have been shown to have anti-cancer effects in the breast [50,38]. AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 protein levels are decreased in breast cancer cell lines and tissue compared to normal cells [51,52]. The AKR enzymes have been implicated in carcinogenesis [53–55,49,56,57], with AKR1C3 and AKR1B10 overexpressed in breast cancers [49,58].

MCF10A and MCF12A cells are well established cell culture models for non malignant human breast epithelial cells [30,59] and show marked upregulation of cytoprotective enzymes as a result of SFN treatment or KEAP1 knockdown. Nevertheless it is important to establish the context in which cytoprotective genes and proteins can be used as biomarkers. In a chemoprevention trial, biomarkers will be used to determine whether the dose of chemopreventive agent administered can reach the putative target cells and upregulate genes and proteins that protect them. Biomarkers that can effectively reflect the pharmacodynamic action of an agent must have specificity and sensitivity. The biomarker measurements should also be robust and reliable and have a highly dynamic range with little baseline activity. Detection of upregulation of genes and proteins is usually the focus for biomarker discovery because measuring an increase in expression above baseline in biological samples is typically easier and more reliable than measuring a decrease in expression. Based on our preclinical studies AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, AKRB10, NQO1 and ALDH3A1 fulfill these criteria and are candidate biomarkers to assess the pharmacodynamic action of SFN in human breast tissue.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Harrys K. C. Jacob for his help with the microarray array data analysis and Santosh Renuse and Praveen Kumar for their help with the SILAC data analysis. This study was supported by the Johns Hopkins Breast Cancer Specialized Programs of Research Excellence P50 CA088843, Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Predoctoral Traineeship Award BC073262, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Sommer Scholars Program and NIH Technology Centers for Networks and Pathways grant U54 RR020839.

Abbreviations

- SFN

sulforaphane

- SILAC

Stable Isotopic Labeling with Amino Acids in Culture

- ER

Estrogen Receptor

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor-E2-Related Factor 2

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1

- ARE

Antioxidant Response Element

- siRNA

small interfering ribonucleic acid

- AKR

aldo-keto reductase, HSD, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson HD, Fu R, Griffin JC, Nygren P, Smith ME, Humphrey L. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:703–715. W-226–735. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahey JW, Zhang Y, Talalay P. Broccoli sprouts: an exceptionally rich source of inducers of enzymes that protect against chemical carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10367–10372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Stephenson KK, Wade KL, Ye L, Talalay P. Safety, tolerance, and metabolism of broccoli sprout glucosinolates and isothiocyanates: a clinical phase I study. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:53–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kensler TW, Chen JG, Egner PA, Fahey JW, Jacobson LP, Stephenson KK, Ye L, Coady JL, Wang JB, Wu Y, Sun Y, Zhang QN, Zhang BC, Zhu YR, Qian GS, Carmella SG, Hecht SS, Benning L, Gange SJ, Groopman JD, Talalay P. Effects of glucosinolate-rich broccoli sprouts on urinary levels of aflatoxin-DNA adducts and phenanthrene tetraols in a randomized clinical trial in He Zuo township, Qidong, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2605–2613. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juge N, Mithen RF, Traka M. Molecular basis for chemoprevention by sulforaphane: a comprehensive review. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1105–1127. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6484-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prochaska HJ, Santamaria AB, Talalay P. Rapid detection of inducers of enzymes that protect against carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2394–2398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thimmulappa RK, Mai KH, Srisuma S, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S. Identification of Nrf2-regulated genes induced by the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane by oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5196–5203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu R, Hebbar V, Kim BR, Chen C, Winnik B, Buckley B, Soteropoulos P, Tolias P, Hart RP, Kong AN. In vivo pharmacokinetics and regulation of gene expression profiles by isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:263–271. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLeod AK, McMahon M, Plummer SM, Higgins LG, Penning TM, Igarashi K, Hayes JD. Characterization of the cancer chemopreventive NRF2-dependent gene battery in human keratinocytes: demonstration that the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway, and not the BACH1-NRF2 pathway, controls cytoprotection against electrophiles as well as redox-cycling compounds. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1571–1580. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, Yamamoto M, Nabeshima Y. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:313–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes JD, McMahon M. NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myzak MC, Dashwood RH. Chemoprotection by sulforaphane: keep one eye beyond Keap1. Cancer Lett. 2006;233:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Tang L. Discovery and development of sulforaphane as a cancer chemopreventive phytochemical. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1343–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Kensler TW, Cho CG, Posner GH, Talalay P. Anticarcinogenic activities of sulforaphane and structurally related synthetic norbornyl isothiocyanates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3147–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornblatt BS, Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Erb M, Fahey JW, Singh NK, Chen MS, Stierer T, Garrett-Mayer E, Argani P, Davidson NE, Talalay P, Kensler TW, Visvanathan K. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of sulforaphane for chemoprevention in the breast. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1485–1490. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konwinski RR, Haddad R, Chun JA, Klenow S, Larson SC, Haab BB, Furge LL. Oltipraz, 3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione, and sulforaphane induce overlapping and protective antioxidant responses in murine microglial cells. Toxicol Lett. 2004;153:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen G, Khor TO, Hu R, Yu S, Nair S, Ho CT, Reddy BS, Huang MT, Newmark HL, Kong AN. Chemoprevention of familial adenomatous polyposis by natural dietary compounds sulforaphane and dibenzoylmethane alone and in combination in ApcMin/+ mouse. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9937–9944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khor TO, Hu R, Shen G, Jeong WS, Hebbar V, Chen C, Xu C, Nair S, Reddy B, Chada K, Kong AN. Pharmacogenomics of cancer chemopreventive isothiocyanate compound sulforaphane in the intestinal polyps of ApcMin/+ mice. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2006;27:407–420. doi: 10.1002/bdd.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu R, Xu C, Shen G, Jain MR, Khor TO, Gopalkrishnan A, Lin W, Reddy B, Chan JY, Kong AN. Gene expression profiles induced by cancer chemopreventive isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the liver of C57BL/6J mice and C57BL/6J/Nrf2 (−/−) mice. Cancer Lett. 2006;243:170–192. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitteringham NR, Abdullah A, Walsh J, Randle L, Jenkins RE, Sison R, Goldring CE, Powell H, Sanderson C, Williams S, Higgins L, Yamamoto M, Hayes J, Park BK. Proteomic analysis of Nrf2 deficient transgenic mice reveals cellular defence and lipid metabolism as primary Nrf2-dependent pathways in the liver. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1612–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhamre S, Sahoo D, Tibshirani R, Dill DL, Brooks JD. Temporal changes in gene expression induced by sulforaphane in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2009;69:181–190. doi: 10.1002/pros.20869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Traka M, Gasper AV, Smith JA, Hawkey CJ, Bao Y, Mithen RF. Transcriptome analysis of human colon Caco-2 cells exposed to sulforaphane. J Nutr. 2005;135:1865–1872. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross-Steinmeyer K, Stapleton PL, Tracy JH, Bammler TK, Strom SC, Eaton DL. Sulforaphane- and phenethyl isothiocyanate-induced inhibition of aflatoxin B1-mediated genotoxicity in human hepatocytes: role of GSTM1 genotype and CYP3A4 gene expression. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116:422–432. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CH, Jeong SJ, Yun SM, Kim JH, Lee HJ, Ahn KS, Won SH, Kim HS, Zhu S, Chen CY, Kim SH. Down-regulation of phosphoglucomutase 3 mediates sulforaphane-induced cell death in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Proteome Sci. 2010;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastrangelo L, Cassidy A, Mulholland F, Wang W, Bao Y. Serotonin receptors, novel targets of sulforaphane identified by proteomic analysis in Caco-2 cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5487–5491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Wade KL, Zhang Y, Shapiro TA, Talalay P. Quantitative determination of dithiocarbamates in human plasma, serum, erythrocytes and urine: pharmacokinetics of broccoli sprout isothiocyanates in humans. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;316:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egner PA, Chen JG, Wang JB, Wu Y, Sun Y, Lu JH, Zhu J, Zhang YH, Chen YS, Friesen MD, Jacobson LP, Munoz A, Ng D, Qian GS, Zhu YR, Chen TY, Botting NP, Zhang Q, Fahey JW, Talalay P, Groopman JD, Kensler TW. Bioavailability of Sulforaphane from Two Broccoli Sprout Beverages: Results of a Short-term, Crossover Clinical Trial in Qidong, China. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:384–395. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subik K, Lee JF, Baxter L, Strzepek T, Costello D, Crowley P, Xing L, Hung MC, Bonfiglio T, Hicks DG, Tang P. The Expression Patterns of ER, PR, HER2, CK5/6, EGFR, Ki-67 and AR by Immunohistochemical Analysis in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2010;4:35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soule HD, Maloney TM, Wolman SR, Peterson WD, Jr, Brenz R, McGrath CM, Russo J, Pauley RJ, Jones RF, Brooks SC. Isolation and characterization of a spontaneously immortalized human breast epithelial cell line, MCF-10. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6075–6086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He X, Marchionni L, Hansel DE, Yu W, Sood A, Yang J, Parmigiani G, Matsui W, Berman DM. Differentiation of a highly tumorigenic basal cell compartment in urothelial carcinoma. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.1002/stem.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harsha HC, Molina H, Pandey A. Quantitative proteomics using stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Jaiswal AK. Regulation of human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase gene. Role of AP1 binding site contained within human antioxidant response element. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15097–15104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh A, Rangasamy T, Thimmulappa RK, Lee H, Osburn WO, Brigelius-Flohe R, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S. Glutathione peroxidase 2, the major cigarette smoke-inducible isoform of GPX in lungs, is regulated by Nrf2. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:639–650. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0325OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Tomso DJ, Chorley BN, Cho HY, Cheung VG, Kleeberger SR, Bell DA. Identification of polymorphic antioxidant response elements in the human genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1188–1200. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishinaka T, Miura T, Okumura M, Nakao F, Nakamura H, Terada T. Regulation of aldo-keto reductase AKR1B10 gene expression: Involvement of transcription factor Nrf2. Chem Biol Interact. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Dufort I, Soucy P, Labrie F, Luu-The V. Molecular cloning of human type 3 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase that differs from 20 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase by seven amino acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:474–479. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yates MS, Tran QT, Dolan PM, Osburn WO, Shin S, McCulloch CC, Silkworth JB, Taguchi K, Yamamoto M, Williams CR, Liby KT, Sporn MB, Sutter TR, Kensler TW. Genetic versus chemoprotective activation of Nrf2 signaling: overlapping yet distinct gene expression profiles between Keap1 knockout and triterpenoid-treated mice. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1024–1031. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, Itoh K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW. Modulation of gene expression by cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Identification of novel gene clusters for cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8135–8145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devling TW, Lindsay CD, McLellan LI, McMahon M, Hayes JD. Utility of siRNA against Keap1 as a strategy to stimulate a cancer chemopreventive phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7280–7285A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501475102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain A, Lamark T, Sjottem E, Larsen KB, Awuh JA, Overvatn A, McMahon M, Hayes JD, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22576–22591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG, Liu S, Schott A, Hayes D, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS, Dontu G. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Orlicky DJ, Matsumoto A, Singh S, Thompson DC, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1 (ALDH1B1) is a potential biomarker for human colon cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Zhang T, Korkaya H, Liu S, Lee HF, Newman B, Yu Y, Clouthier SG, Schwartz SJ, Wicha MS, Sun D. Sulforaphane, a dietary component of broccoli/broccoli sprouts, inhibits breast cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2580–2590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gasper AV, Traka M, Bacon JR, Smith JA, Taylor MA, Hawkey CJ, Barrett DA, Mithen RF. Consuming broccoli does not induce genes associated with xenobiotic metabolism and cell cycle control in human gastric mucosa. J Nutr. 2007;137:1718–1724. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.7.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonnesen C, Eggleston IM, Hayes JD. Dietary indoles and isothiocyanates that are generated from cruciferous vegetables can both stimulate apoptosis and confer protection against DNA damage in human colon cell lines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6120–6130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi M, Fujii J, Miyoshi E, Hoshi A, Taniguchi N. Elevation of aldose reductase gene expression in rat primary hepatoma and hepatoma cell lines: implication in detoxification of cytotoxic aldehydes. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:749–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Penning TM, Burczynski ME, Jez JM, Hung CF, Lin HK, Ma H, Moore M, Palackal N, Ratnam K. Human 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms (AKR1C1-AKR1C4) of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily: functional plasticity and tissue distribution reveals roles in the inactivation and formation of male and female sex hormones. Biochem J. 2000;351:67–77. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiebe JP, Muzia D, Hu J, Szwajcer D, Hill SA, Seachrist JL. The 4-pregnene and 5alpha-pregnane progesterone metabolites formed in nontumorous and tumorous breast tissue have opposite effects on breast cell proliferation and adhesion. Cancer Res. 2000;60:936–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiebe JP, Lewis MJ. Activity and expression of progesterone metabolizing 5alpha-reductase, 20alpha-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase and 3alpha(beta)-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductases in tumorigenic (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T-47D) and nontumorigenic (MCF-10A) human breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2003;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ji Q, Aoyama C, Nien YD, Liu PI, Chen PK, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Stolz A. Selective loss of AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 in breast cancer and their potential effect on progesterone signaling. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7610–7617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee EK, Regenold WT, Shapiro P. Inhibition of aldose reductase enhances HeLa cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs and involves activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:859–868. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saraswat M, Mrudula T, Kumar PU, Suneetha A, Rao Rao TS, Srinivasulu M, Reddy B. Overexpression of aldose reductase in human cancer tissues. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CR525–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Penning TM. AKR1B10: a new diagnostic marker of non-small cell lung carcinoma in smokers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1687–1690. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park JH, Mangal D, Tacka KA, Quinn AM, Harvey RG, Blair IA, Penning TM. Evidence for the aldo-keto reductase pathway of polycyclic aromatic trans-dihydrodiol activation in human lung A549 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6846–6851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802776105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gallego O, Belyaeva OV, Porte S, Ruiz FX, Stetsenko AV, Shabrova EV, Kostereva NV, Farres J, Pares X, Kedishvili NY. Comparative functional analysis of human medium-chain dehydrogenases, short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases and aldo-keto reductases with retinoids. Biochem J. 2006;399:101–109. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma J, Yan R, Zu X, Cheng JM, Rao K, Liao DF, Cao D. Aldo-keto reductase family 1 B10 affects fatty acid synthesis by regulating the stability of acetyl-CoA carboxylase-alpha in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3418–3423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paine TM, Soule HD, Pauley RJ, Dawson PJ. Characterization of epithelial phenotypes in mortal and immortal human breast cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;50:463–473. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]