Abstract

Chromosome 8q24 is the most commonly amplified region across multiple cancer types, and the typical length of the amplification suggests that it may target additional genes to MYC. To explore the roles of the genes most frequently included in 8q24 amplifications, we analyzed the relation between copy number alterations and gene expression in three sets of endometrial cancers (N = 252); and in glioblastoma, ovarian, and breast cancers profiled by TCGA. Among the genes neighbouring MYC, expression of the bromodomain-containing gene ATAD2 was the most associated with amplification. Bromodomain-containing genes have been implicated as mediators of MYC transcriptional function, and indeed ATAD2 expression was more closely associated with expression of genes known to be upregulated by MYC than was MYC itself. Amplifications of 8q24, expression of genes downstream from MYC, and overexpression of ATAD2 predicted poor outcome and increased from primary to metastatic lesions. Knockdown of ATAD2 and MYC in seven endometrial and 21 breast cancer cell lines demonstrated that cell lines that were dependent on MYC also depended upon ATAD2. These same cell lines were also the most sensitive to the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor Trichostatin-A, consistent with prior studies identifying bromodomain-containing proteins as targets of inhibition by HDAC inhibitors. Our data indicate high ATAD2 expression is a marker of aggressive endometrial cancers, and suggest specific inhibitors of ATAD2 may have therapeutic utility in these and other MYC-dependent cancers.

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common pelvic gynecologic malignancy, with a lifetime risk among women of 2–3% [1]. Approximately 75% of tumors are confined to the uterine corpus at diagnosis and are resected. However, 15%–20% of these tumors relapse. These tumors, and tumors that are metastatic at presentation, respond poorly to chemotherapy or radiation and are generally fatal [1], [2].

There is a need for novel markers to identify patients with high risk of relapse, and to develop new therapies for patients with metastatic disease [3], [4]. Unfortunately, research towards these goals is heavily underrepresented in endometrial cancer compared to other cancer types such as breast and ovarian cancers. One approach is to identify genes that, when altered by somatic genetic events, drive tumor progression. These alterations can then serve as markers of aggressive cancers and the genes can serve as potential therapeutic targets.

The most frequent focal amplification in endometrial cancer is on 8q24 [5]. Indeed, 8q24 is the most commonly amplified region across multiple cancer types [6], and this amplification is a negative prognostic marker in several cancers [7]. Although MYC is a likely target [6], the effects of this amplification in endometrial cancer have never been dissected. Indeed, it is possible that it targets multiple genes, as has been shown for amplifications elsewhere in the cancer genome [8]. For example, a neighboring gene, ATAD2, has been found to be a co-regulator of MYC and overexpression of ATAD2 has been associated with poor prognosis in breast, lung, and prostate cancers [9], [10], [11].

We explore the role of the 8q24 amplification in endometrial cancer through integrative genomic analyses of primary and metastatic endometrial cancers with comprehensive clinical data, and identify ATAD2 as an additional target of the 8q24 amplification in these cancers. We identify copy number gain of ATAD2 as a regulator of ATAD2 expression, present the first data linking ATAD2 overexpression to MYC activation, and provide functional data suggesting ATAD2 as a therapeutic target in MYC-dependent cancers.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The collection of endometrial carcinoma primaries and metastases for this study was approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (961478-2), Norwegian Social Sciences Data Services (15501) and the “Regional Research Ethics.

Committee in Medicine, Western Norway” (reference 052.01). All the participants gave written informed consent.

Patient Series

Endometrial carcinoma primaries and metastases were collected from patients treated at Haukeland University Hospital, Norway as previously described [5]. Tumors collected for the primary investigation and qPCR validation series were frozen immediately upon resection; tumors collected for FISH were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded. Patients were followed from primary surgery until October 2010 or death. The copy-number profiles of the primary investigation series, and the expression profiles (Agilent 21 k and 22 k oligoarrays) from a subset of 57 tumors, were published previously [5].

RNA Analysis

RNA was extracted and hybridized to Agilent 44K arrays (Cat.no. G4112F) according to manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described [5]. Signal intensities were evaluated using BRB-ArrayTools (National Cancer Institute, USA). The arrays were batch median normalized.

Real-time Quantitative PCR

cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg RNA using High capacity RNA to cDNA kits (Applied Biosystems). Expression of ATAD2 and MYC was determined using TaqMan gene expression assays Hs00204205 and Hs00905030 respectively (Applied Biosystems) and all samples were run on microfluidic cards per manufacturer’s instructuions, using GAPDH-Hs99999905_m1 as endogenous control. Samples were run in triplicate and analyzed in RQ manager (Applied Biosystems).

FISH

Tissue microarrays (TMAs) representing the highest-grade areas in each tumor were prepared as previously reported [12] and treated at 56C° overnight before hybridization. FISH was done using the MYC Spectrum Orange FISH probe kit and Chromosome enumeration probe 8 (CEP8) (Vysis) according to manufacturer’s instructions, as previously reported [13]. Counting was performed in areas of optimal tissue digestion and no overlapping nuclei. Probe and control signals were counted in 40–60 cells within areas of optimal tissue digestion and no overlapping nuclei. Amplifications were scored when the MYC/CEP8 ratio was >1.0.

TCGA Validation Dataset

We accessed level 3 data from the TCGA data portal in November and December 2010. For breast cancer we obtained gene expression data for 279 tumors and 24 normal controls (Agilent 244K expression arrays), and copy-number from 176 tumors (Affymetrix SNP 6.0 Arrays). For ovarian cancer we obtained gene expression (Agilent 244K expression arrays) and copy-number (Agilent 1M arrays) data from 514 and 489 tumors, respectively. For glioblastoma we obtained gene expression data from 385 tumors and 10 normal controls (Affymetrix U133A arrays) and copy-number data from 261 tumors (Agilent 244K arrays).

Cell Viability

Lentiviral vectors encoding shRNAs specific for ATAD2, MYC, and the controls GFP, LACZ1, and LACZ2 (Table S1) were obtained from The RNAi Consortium. Lentivirus was produced by transfection of 293T cells with vectors encoding each shRNA (5 µg) with packaging plasmids encoding PSPAX2 and PDM2.G using Fugene HD (Roche). Lentivirus-containing supernatant was collected 48 and 72 h after transfection, pooled, and stored at −80 °C. Cells were infected in polybrene-containing media, centrifuged at 1,000 g for 30 min, and selected in puromycin (2.5 µg ml−1) starting 24 h after infection.

Cancer cell lines were obtained from ATCC, DSMZ, ECACC and HSRRB, and grown according to supplier’s instructions (Table S2). Cell viability after RNAi was measured in 96-well plates. Eight wells seeded with cells were infected using 1∶30 dilutions of virus containing each shRNA. Half of the wells underwent puromycin selection, and cell viability was measured using Cell-Titer Glo (Promega) one week later. The values from each quadruplicate were averaged; “outlier” wells were excluded if the replicate wells had SD/mean >0.2 and excluding the well improved the variance. The mean ATAD2- and MYC- hairpin values were normalized to the mean values from the GFP control.

To determine Trichostatin-A sensitivity, Trichostatin-A (Sigma) (0.040 to 10 µM) and vehicle (DMSO) control were each added to three wells containing each cell line on 96-well plates. Cell viability was determined after 72 hours using Cell-Titer Glo (Promega).

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed with PBS, harvested, lysed using RIPA lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and centrifuged at 16,000×g. Supernatant was mixed with 4X SDS sample buffer, boiled for 7 minutes, and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 4–12% gradient gels. Blots were probed with antibodies against ATAD2 (HPA029424, Sigma), MYC (sc-764, Santa Cruz) and actin (sc-1615, Santa Cruz).

Statistics

Molecular data was related to clinical phenotype using Pearson’s χ2 or two-sided Student’s t test as appropriate. We used multivariate linear regression analysis for the prediction of ATAD2 expression levels. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were performed by log rank and Mantel-Cox methods, respectively. “MYC signaling strength” and gene expression levels were presented as Z-scores.

Results

Assessment of MYC as a Target of the 8q24 Amplification

Extensive biological data support MYC as an oncogene [14], and 8q24, harboring MYC, is the most common amplified region across multiple cancer types [6]. However, the importance of MYC activation in endometrial cancer is essentially unknown.

We performed an integrated analysis of copy-number and expression data to look for evidence that MYC is a target of 8q24 amplification in endometrial cancer. We evaluated expression data from a series of 82 endometrial cancers obtained in a single county in Norway, with corresponding genome-wide copy-number data from 70 tumors (the “primary investigation series”). Sixteen of these tumors (23%) had 8q24 amplification. Most of these amplifications were low-level, ranging up to a copy-number of 4.7. We validated our results in four additional datasets. Two of these represent samples with genome-wide expression profiling: an “internal validation series” for which we generated data from 40 primary and 19 metastatic endometrial cancers recruited from the same region in Norway, and an “external validation series” representing previously published expression profiles from 111 tumors [5]. The other two validation sets represent samples analyzed with focused assays: a “qPCR series” of 162 samples and a “FISH series” of 399 samples. Patient characteristics and histopathological variables for all of our internal datasets are shown in Table S3.

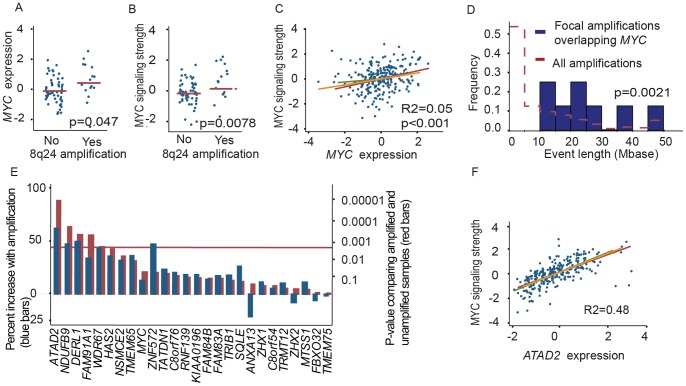

We found that both MYC and genes upregulated by MYC were overexpressed in endometrial cancers with 8q24 amplification relative to endometrial cancers without it (p = 0.047 and p = 0.0078, respectively) (Figures 1a–b). We used a previously published list of 68 genes found to be upregulated by MYC across multiple contexts and assays (Table S4; www.myccancergene.org) [15] and scored their overexpression (“MYC signaling strength”) using GSEA [16]. We also tested five additional MYC activation signatures obtained from the “Gene Set Enrichment Database”, reflecting the activation of MYC in different contexts. Four of these were expressed at higher levels in endometrial cancers with 8q24 amplification (Figure S1a).

Figure 1. MYC, ATAD2 and 8q24 associations.

(a) MYC expression and (b) MYC signaling are both increased among endometrial cancers with 8q24 amplification. (c) Variations in MYC expression only explain a small proportion of the variation in MYC signaling. Linear fits are shown in red, yellow, and green for the primary investigation series, internal validation series, and external validation series, respectively. (d) The lengths of the amplifications that contain MYC are significantly larger than expected compared to amplifications observed elsewhere in these cancers. (e) Among 26 genes in the 8q24 peak with corresponding expression data, expression of ATAD2 is most strongly and significantly associated with amplification. Blue bars show the percent increase in gene expression and red bars show the p-values. The significance threshold is Bonferroni-corrected for multiple hypotheses. (f) Expression of ATAD2 is highly correlated with MYC signaling strength. Linear fits are shown as in panel c.

However, variations in MYC expression itself only explained a small proportion of variations in MYC signaling strength (R2 = 0.11, p = 0.002) (Figure S1b). We obtained similarly weak results in the internal and external validation datasets (R2 = 0.00, p = 0.34 and R2 = 0.06, p = 0.012, respectively; Figure S1b). Across all three datasets, variations in MYC expression only account for 5% of variations in MYC signaling strength (R2 = 0.05, Figure 1c).

Moreover, 8q24 amplifications are longer than the typical distribution of amplification sizes in endometrial cancer (p = 0.0021) (Figure 1c), and usually involve multiple genes. We therefore hypothesized that 8q24 amplifications may target additional genes, some of which may function through increasing MYC signaling. To identify these, we evaluated all 26 genes in the peak region of amplification on 8q24 for which we had expression data, to identify genes whose expression correlated most strongly with amplification.

Expression of ATAD2 Correlates Strongly with 8q24 Amplification and MYC Signaling

Expression of ATAD2 was more strongly associated with amplification of 8q24 than was expression of any other gene in the peak region of the amplification (p-value = 2.77E-06) (Figure 1d). Four other genes, NDUFB9, DERL1, FAM91A1, and WDR67, were significantly upregulated by 8q24 amplification, though less strongly than ATAD2.

Expression of ATAD2 also correlated with MYC signaling strength more strongly than did expression of any other gene in the 8q24 peak region (R2 = 0.48, p<0.001; Figure 1e, Figure S1b). Indeed, the association between ATAD2 expression and MYC signaling strength was observed even among samples without 8q24 amplification (R2 = 0.48, p<0.001). The correlation between ATAD2 expression and MYC signaling strength was more than twice as strong as the next most significantly associated gene (NDUFB9) and stronger than for MYC itself (R2 = 0.05; Figure 1c). ATAD2 is not one of the 68 genes in the MYC activation signature, and to our knowledge MYC has not been found to modulate expression of ATAD2 [15]. However, ATAD2 was previously found to bind to MYC and to the E-box region of several MYC target genes, and ATAD2 levels were found to be limiting for MYC-dependent transcription [9].

Both genome-wide validation series also exhibited the correlation between MYC signaling and ATAD2 expression (R2 = 0.54, p<0.001 and R2 = 0.45, p<0.001 in the internal and external validation series, respectively) and the relative lack of correlation with MYC expression (R2 = 0.00, p = 0.33 and R2 = 0.06, p = 0.012; Figures 1f and S1b). Expression of ATAD2 also correlated with four of the five additional signatures of MYC activation, and correlated more strongly with these signatures than did expression of MYC itself (Table 1). The last signature showed no association with ATAD2 or MYC expression.

Table 1. Associations between other MYC activation gene sets and ATAD2- and MYC expression.

| ATAD2 | MYC | ||||||||

| Gene set | R2 | P-value | P-value* | R2 | P-value | P-value* | |||

| Schumacher myc up† | 0.45 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Primary Investigation Series | 0.43 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.025 | |||

| Internal validation Series | 0.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.800 | 0.252 | |||

| External validation Series | 0.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.49 | <0.001 | 0.026 | |||

| Coller myc up‡ | 0.35 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.002 | |||

| Primary Investigation Series | 0.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.006 | |||

| Internal validation Series | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.186 | 0.427 | |||

| External validation Series | 0.43 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.08 | |||

| Yu cmyc up§ | 0.62 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.987 | |||

| Primary Investigation Series | 0.62 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.290 | 0.612 | |||

| Internal validation Series | 0.68 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.252 | 0.973 | |||

| External validation Series | 0.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.006 | 0.632 | |||

| Myc oncogenic signature¶ | 0.20 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.23 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Primary Investigation Series | 0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.004 | |||

| Internal validation Series | 0.08 | 0.042 | <0.001 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.133 | |||

| External validation Series | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Lee myc up|| | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.150 | 0.147 | |||

| Primary Investigation Series | 0.02 | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.00 | 0.825 | 0.79 | |||

| Internal validation Series | 0.00 | 0.656 | 0.587 | 0.00 | 0.612 | 0.553 | |||

| External validation Series | 0.18 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.002 | 0.051 | |||

R2 and p-values are derived from a linear regression of the sum of expression values within the gene set against ATAD2 or MYC expression.

Adjusted for ATAD2 or MYC expression.

Genes up-regulated in P493-6 cells (Burkitt’s lymphoma) induced to express MYC (Schumacher).

Genes regulated by forced expression of MYC in 293T (transformed fetal renal cell).

Genes up-regulated in B cell lymphoma tumors expressing an activated form of MYC.

Genes selected in supervised analyses to discriminate cells expressing c-Myc from control cells expressing GFP. Myc oncogeneic.

Genes up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) induced by overexpression of MYC.

Amplification of 8q24 and Expression of ATAD2, but not MYC, are Associated with Disease Progression

Among the 70 endometrial cancers for which we had genome-wide SNP array data, 8q24 amplification was associated with reduced progression-free survival (p = 0.024) and increased risk for disease-specific death (p = 0.043). Amplification of 8q24 was most frequent in non-endometrioid (p = 2.98E-05) and high-grade tumors (p = 2.90E-08) (Table S5), features also associated with aggressive cancers [17].

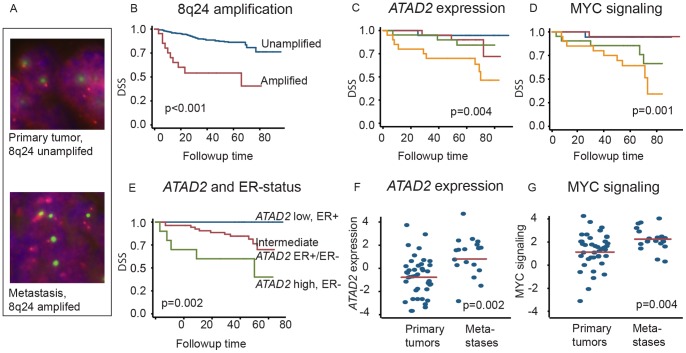

We confirmed 8q24 amplification is associated with poor prognosis using FISH in an independent series of 399 endometrial cancers. Twenty cancers (5%) exhibited increased 8q24 copy-numbers relative to the chromosome 8 centromere (Figure 2a). These were associated with 64% 5-year survival, vs. 85% for cancers without 8q24 amplification (p<0.001) (Figure 2b). A similar pattern was seen for recurrence free survival (p = 0.001). Amplification of 8q24 was also associated with high FIGO stage (p = 0.003), non-endometrioid histological subtype (p<0.001), and high grade (p<0.001) (Table S5).

Figure 2. Amplification of 8q24, ATAD2 overexpression and increased MYC signaling are associated with poor prognosis.

FISH probes against 8q24 (red) and the chromosome 8 centromere (green) in a primary tumor and the paired metastasis show amplification only in the latter (a) (b) Among 399 patients assessed by FISH, those with 8q24 amplifications have worse outcome. In the primary investigation series, tumors among the highest quartiles of (c) ATAD2 expression and (d) MYC signaling strength also had increased risk of disease-specific death. (e) Estrogen receptor negative (ER−) tumors with ATAD2 expression in the top quartile were also associated with a high risk of disease-specific death; the risk was much lower among estrogen receptor positive (ER+) tumors with ATAD2 expression in the bottom quartile. (f) ATAD2 expression and (g) MYC signaling are both higher among metastases than primary tumors in the internal validation series.

High expression of ATAD2 and MYC signaling were also associated with increased risk of cancer progression (p = 0.003 and p = 0.015, respectively), cancer-specific death (p = 0.004 and p = 0.001) (Figures 2c–d), and other poor-prognosis features. ATAD2 expression was higher in non-endometrioid, high-grade and ER negative tumors (p<0.001, p<0.001, and p = 0.02 respectively; Table S6); high MYC signaling was associated with poorly differentiated (p = 0.0016) and non-endometrioid (p<0.001) cancers. Expression of ATAD2 was also negatively associated with expression of ESR1 (R2 = 0.10, p = 0.005). Similarly, prior studies have found that ATAD2 expression is higher in triple negative breast cancer tumors [18] and is downregulated by estrogen in cell culture [19].

Indeed, ATAD2 expression was an independent predictor for disease-specific death (HR = 1.83, p = 0.027) and disease progression (HR = 1.62, p = 0.011) after adjusting for ER status. ER-negative tumors with upper-quartile ATAD2 expression were particularly lethal (HR = 4.1, p = 0.002; Figure 2e).

We confirmed these results by assessing ATAD2 expression by quantitative PCR and ER status by immunohistochemistry in our qPCR validation series of 162 additional tumors. Among these, ER-negative tumors with upper-quartile ATAD2 expression were associated with even worse outcomes than in the primary series (HR = 6.8, p<0.001) (Figure S1c). High ATAD2 expression also remained associated with increased risk of disease-specific death (p = 0.0043) and shorter progression-free survival (p = 0.016). After adjusting for ER status, ATAD2 expression continued to predict disease-specific death (HR = 1.86, p = 0.018) but only trended towards an association with disease progression (HR = 1.31, p = 0.11). Expression of ATAD2 was also higher in high-grade (p<0.001), non-endometrioid (p = 0.005), and ER-negative tumors (p = 0.02) (Table S6).

In contrast, MYC expression was not associated with progression or risk of disease-specific death in either our primary investigation series (p = 0.07 and p = 0.68 respectively) or the qPCR validation series (p = 0.53 and p = 0.28 respectively). High expression of MYC was associated with high grade in both series (p<0.001 and p = 0.02, respectively), and with non-endometrioid histology in the primary investigation series (p = 0.03) (Table S6).

Metastases also exhibit more 8q24 amplification, ATAD2 expression, and MYC signaling strength than primary tumors. Relative to primary tumors, metastases exhibited 2.4× higher rates of focal 8q24 amplification by FISH (14.3%; p<0.007). Among the 399 patients in the FISH series, 49 had paired primary and metastatic tumors. Five of these samples (10%) did not exhibit 8q24 amplification in the primary but acquired it in the metastasis. Only one sample (2%) exhibited the opposite pattern. To examine ATAD2 expression and MYC signaling, we also compared the 42 primary tumors with the 19 metastases in our internal validation series. Both ATAD2 expression and MYC signaling strength were higher in the metastases (p = 0.002 and 0.004 respectively; Figure 2f–g), including among 8 patients with paired primary tumors and metastases (p = 0.01 and 0.05 respectively).

Extension to Other Cancer Types and Normal Tissue

We also investigated whether 8q24 amplification is associated with increased ATAD2 expression in other cancer types. Specifically, we used data from 514 ovarian cancers, 279 breast cancers, and 385 glioblastomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas [20], [21]. These included expression data from adjacent normal tissue for 24 breast cancers and 10 glioblastomas. 8q24 amplifications were observed in 72% (N = 126) of the breast cancers, 74% (N = 364) of the ovarian cancers, and 10% (N = 27) of the glioblastomas. ATAD2 was co-amplified to the same level as MYC in nearly all tumors (as it was among our endometrial cancers; Figure S1d–g).

Expression of ATAD2 correlated with 8q24 amplification among all three cancer types (R2 = 0.47, 0.11, and 0.36 for breast cancers, glioblastomas, and ovarian cancers respectively; p<0.001 in all cases; Table S7), and was 2.6× and 2.5× higher among the cancers relative to normal tissue in breast cancer and glioblastoma, respectively (p<0.001 in both cases). MYC expression correlated less strongly with 8q24 amplification in all three cancer types (R2 = 0.12, 0.07, and 0.10 for breast cancers, glioblastomas, and ovarian cancers respectively; p<0.001 in all cases). MYC expression in breast cancers was surprisingly half that of normal tissue (p<0.001); in glioblastoma it was higher by a factor of 3.5 (p<0.001).

ATAD2 expression also correlated with MYC signaling in all three cancer types (R2 = 0.11, 0.21, and R2 = 0.31, respectively for breast cancers, glioblastomas, and ovarian cancers; p<0.001 in all cases), and was more strongly correlated with MYC signaling strength than MYC expression was (R2 = 0.10, p<0.001; R2 = 0.09, p<0.001; and R2 = 0.02, p = 0.003 in the three cancer types).

ATAD2 Expression is Correlated to E2F Gene Expression and ATAD2 Copy Number in an Additive Manner

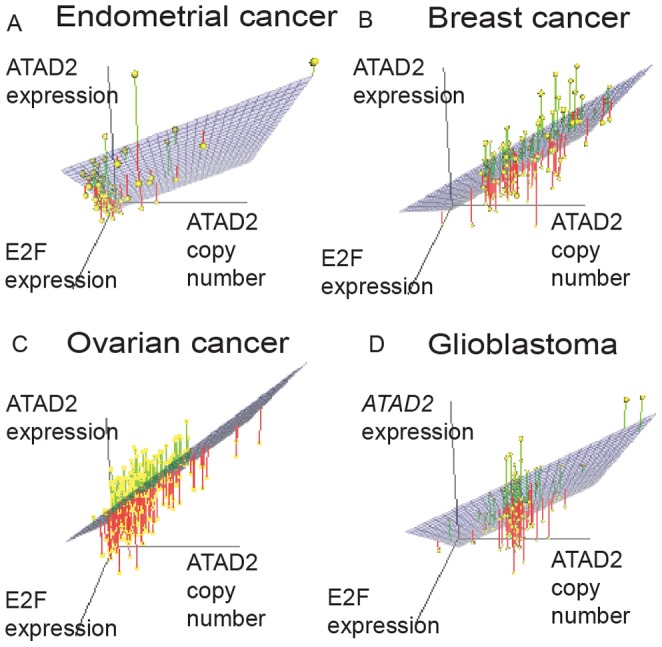

We also explored the relative contributions of E2F, estrogen, and copy-number on ATAD2 expression. The ATAD2 promoter region contains binding sites for several E2F proteins and previous functional data have shown that E2F increases ATAD2 expression in cell culture [9], [22]; ATAD2 has also been induced by estrogen [23]. In our data, expression of every E2F transcription factor was associated with ATAD2 expression, but only the inclusion of E2F1, E2F2 and E2F8 improved the overall fit of a model predicting ATAD2 expression from ATAD2 copy-number and ESR1 expression. The expression levels of these three genes were highly correlated, and we focused on E2F1.

We found that ATAD2 copy-number, ESR1 expression and E2F1 expression explained 77% of the variation in ATAD2 expression in endometrial cancer, and each of the predictor variables remained significantly associated with ATAD2 expression in the adjusted model (Figure 3a and Table S7). We also found that ATAD2 copy-number and E2F expression independently predicted ATAD2 expression in breast cancer, ovarian cancer and glioblastoma (Figure 3b–d and Table S7). ESR1, which was less strongly associated with ATAD2 expression, was significant in the adjusted model only in endometrial cancer (p = 0.016) and glioblastoma (p<0.001), not in ovarian or breast cancer. These data suggest that the copy-number of ATAD2 is an important determinant of ATAD2 expression even in the context of other cellular regulatory mechanisms.

Figure 3. 3-D-plots showing ATAD2 expression and -copy-number and E2F1 expression.

(a) Endometrial cancer, (b) breast cancer, (c) ovarian cancer, and (d) glioblastoma. Yellow dots represent the samples and the blue plate is the predicted 3-D fit. The green and red lines are the distance between the predicted fit and the actual observations for samples above and below the 3D-fit plate, respectively.

Dependency on MYC Predicts Dependency on ATAD2 and Response to HDAC Inhibitors in Endometrial- and Breast Cancer Cells

The results above led us to hypothesize that ATAD2 expression promotes MYC signaling and that endometrial cancer cells that are dependent upon MYC would also be dependent upon ATAD2. We measured the effect on viability of shRNA knockdowns of ATAD2 and MYC in seven endometrial cancer cell lines. We used two shRNAs against each gene, selecting those that exhibited the greatest reduction of protein expression among six and three shRNAs screened against ATAD2 and MYC respectively (Figure 4a, b).

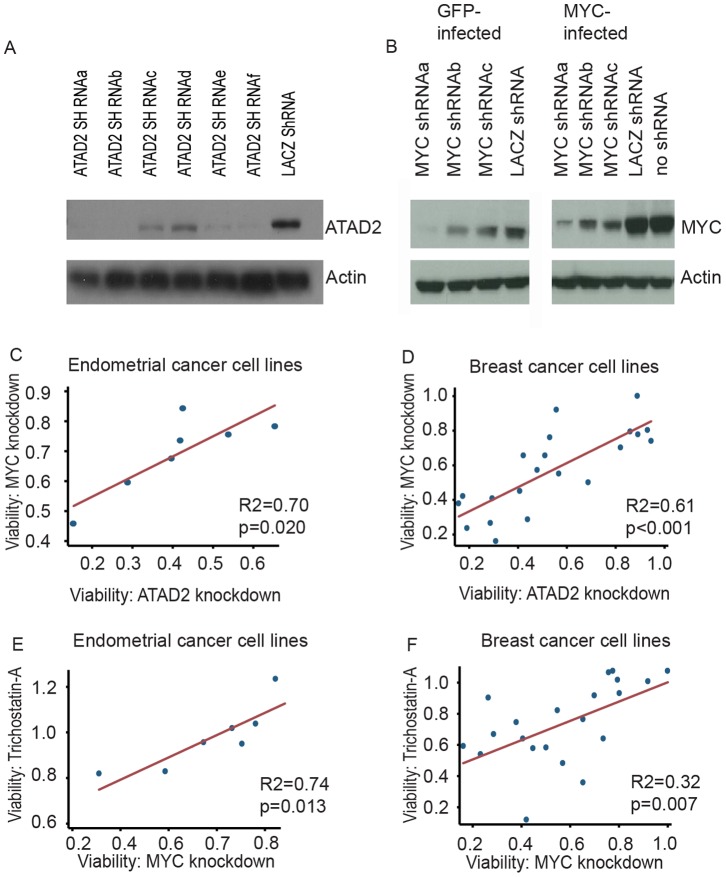

Figure 4. Correlation between effects of ATAD2 and MYC knockdown.

Western blots for (a) ATAD2 and (b) MYC indicate extent of knockdown with six shRNAs against ATAD2 and three shRNAs against MYC, respectively. ATAD2 experiments were performed in KLE cells and MYC experiments were performed in TE9 cells infected with GFP control and MYC vectors. Subsequent experiments used ATAD2 shRNAs a and e, and MYC shRNAs a and b. Reductions in cell viability among seven endometrial cancer cell lines (c) and 21 breast cancer cell lines (d) were highly correlated after knockdown of ATAD2 or MYC and after knockdown of MYC and treatment with the HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin-A (1.25 µM) (e–f).

Knockdown of either ATAD2 or MYC resulted in highly correlated decreases in viability across the seven cell endometrial cancer lines (R2 = 0.70, p = 0.020; Figure 4c). In two cases, we observed over 75% reductions in viability. We found no association between expression of ATAD2 or MYC or 8q24 copy number and sensitivity to ATAD2 or MYC knockdown.

These results suggested that MYC-dependent cancers of other types might also be dependent on ATAD2. No decrease in proliferation had previously been seen with ATAD2 knockdown in TIG3-T or U2OS cells [9]. When we tested a larger panel of 21 breast cancer lines, however, we confirmed the strong correlation between decrease in viability after knockdown of ATAD2 or MYC (R2 = 0.61, p<0.001; Figure 4d).

The association between dependency on MYC and ATAD2 suggests ATAD2 as a therapeutic target in MYC-dependent cancers. Whereas MYC has long been a known oncogene, clinical approaches to block MYC signaling have not yet been successful. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, however, have been shown to indirectly inhibit bromodomain-containing proteins such as ATAD2 [24].

We used the Connectivity Map [25] to identify compounds whose signatures anticorrelated with the MYC signaling signature. Among the 1309 small molecules represented by the Connectivity Map, the signature of the HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin-A was most anticorrelated with the MYC signaling signature. (p-value<0.00001; Table S8). We also generated a signature of aggressive disease from the primary investigation series, using the 50 most over- and under-expressed genes in patients with metastatic disease compared to patients without metastatic disease. We found the Trichostatin-A signature was also the most anticorrelated with this signature of aggressive disease, tied with signatures of four other molecules (p<0.00001; Table S8).

To functionally confirm the relation between Trichostatin-A and MYC dependency, we tested all endometrial cancer and breast cancer cell lines for growth inhibition by Trichostatin-A and compared the results to MYC knockdown. Trichostatin-A inhibited growth in the same cell lines which were dependent on MYC both in the endometrial (R2 = 0.74, p = 0.013; Figure 4e), and in the breast cancer cell lines (R2 = 0.31, p = 0.007; Figure 4f) but the overall efficacy of Trichostatin-A at reducing cell viability was lower among the doses we tested (0.04–10 µM) (Table S9) than were the effects of MYC or ATAD2 knockdown.

Discussion

Our data suggest that ATAD2 overexpression in human endometrial cancers is a consequence of 8q24 amplification and associated with MYC pathway activation. We also find that ATAD2 overexpression is associated with E2F activation and poor prognosis. Analyses of TCGA data suggest similar relationships between ATAD2, 8q24 amplification, and MYC pathway activation in glioblastoma, breast, and ovarian cancers. We also find that endometrial and breast cancer cell lines that are dependent upon MYC expression also depend upon expression of ATAD2.

High expression of ATAD2 has previously been found to be associated with an unfavorable prognosis in breast, lung, and prostate cancers and it has been suggested that ATAD2 contributes to the development of aggressive cancer through linking of the E2F and MYC pathways [9], [10], [11]. We demonstrate an association between high ATAD2 expression and negative outcome in endometrial cancer, using clinically well-characterized test and validation datasets. We also find that progression from primary to metastatic endometrial cancer is associated with a further increase of MYC signaling and ATAD2 expression.

Ciro et al [9] previously showed that ATAD2 interacts with MYC in breast cancer cell lines and is overexpressed in 8q24 amplified breast cancers. Our results indicate that, in endometrial cancers, expression of ATAD2 is more highly correlated with 8q24 amplification than is expression of its neighbors (including MYC), and that ATAD2 amplification and overexpression are strongly associated with multiple measures of MYC pathway activation in human tumors.

The finding of cooperative effects between MYC and coamplified genes on 8q24 is not entirely surprising. Indeed, the concept of oncogene cooperation was established through the study of positive interactions between MYC and other oncogenes such as BCL2 [26]. Moreover, clustered genes are often functionally related [27]. The relevance of this phenomenon in cancer has been shown for the genes MMP13, Birch2, and Birch3, which are functionally related oncogenes contained on the same amplification in osteosarcoma [28], and for BIRC2 and YAP1, cooperating oncogenes in an amplification in hepatocellular carcinomas [8].

Such a mechanistic association between ATAD2 and MYC, and the finding that MYC-dependent cells are sensitive to ATAD2 knockdown, suggest ATAD2 as a therapeutic target in MYC-dependent cancers. Although MYC has long been known as an oncogene [14] and is a promising drug target, it has not been successfully targeted therapeutically. Small molecule inhibitors have, however, been generated against other bromodomain-containing proteins [29]. Indeed, inhibition of the bromodomain-containing protein BRD4 has recently been suggested as an alternative approach to targeting MYC [30]. HDAC inhibitors also indirectly inhibit bromodomain-containing proteins by inducing histone hyperacetylation, thus probably diverting the specific bromodomain proteins from their targets [24]. This may account for some of the effectiveness of HDAC inhibitors as cancer therapeutics [30], and we found cell lines that were sensitive to knockdown of MYC or ATAD2 were also sensitive to the HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin-A. However, the reduction in viability after application of Trichostatin-A was smaller than the reduction in viability after MYC or ATAD2 knockdown. It is possible that a more direct inhibitor of ATAD2 would be more effective in these cells.

Major obstacles to treatment of patients with endometrial cancer include a lack of targeted therapeutics and of prognostic indicators. Indeed, endometrial cancer remains understudied relative to other cancer types. We find that ATAD2 amplification and expression is a prognostic marker in endometrial cancer and our findings suggest that development of specific ATAD2 inhibitors is a promising approach to treatment of endometrial and other MYC driven cancers.

Supporting Information

a) Five additional MYC activation genes sets obtained from the literature and their relative expression in 8q24 amplified versus unamplified samples. b) The correlation between MYC signaling strength and MYC- (left) and ATAD2- (right) gene expression in the primary investigation series and in the internal and external validation series. c) Estrogen receptor negative (ER−) tumors with ATAD2 expression in the top quartile were associated with a high risk of disease-specific death; the risk was much lower among estrogen receptor positive (ER+) tumors with ATAD2 expression in the bottom quartile. d-g) Results from the qPCR validation series. The copy-number of MYC and ATAD2 genes are highly correlated in endometrial cancer (d), glioblastoma (e), ovarian cancer (f) and breast cancer (g).

(EPS)

Details about the shRNA used in the study.

(DOCX)

Names, origins and culture conditions for the cell lines used.

(DOCX)

Patient characteristics and histopathological variables for the endometrial carcinoma series studied.

(DOCX)

Genes in the MYC signaling signature.

(DOCX)

Histopathological variables according to amplification of the 8q24 locus.

(DOCX)

Gene expression of ATAD2 and MYC according to histopathological variables.

(DOCX)

Prediction of ATAD2 gene expression by ATAD2 copy number, ESR1 gene expression and E2F1 gene expression.

(DOCX)

Compounds with gene signatures anticorrelated to metastatic disease or the MYC signaling signature.

(DOCX)

The associations between the sensitivity of 7 endometrial cancer cell lines to MYC knockdown and Tricostatin-A at different concentrations.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Britt Edvardsen, Mari Kyllesø Halle, Ingjerd Bergo, Tormund S Njølstad, Erlend S Njølstad, Gerd Lillian Hallseth, Bendik Nordanger, Beth Johannessen and Hua My Hoang for technical assistance.

Funding Statement

Financial support: Helse Vest Grants 990172 (MBR), 911351, 911624, and 911626 (HBS); the University of Bergen; the Norwegian Cancer Society; the Research Council of Norway Grants 205404 and 193373 (HBS); the National Cancer Institute (K08CA122833 and U54CA143798); and a V Foundation Scholarship (RB). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, et al. (2005) Endometrial cancer. Lancet 366: 491–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rose PG (1996) Endometrial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 335: 640–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dedes KJ, Wetterskog D, Ashworth A, Kaye SB, Reis-Filho JS (2011) Emerging therapeutic targets in endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8: 261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salvesen HB, Haldorsen IS, Trovik J (2012) Markers for individualised therapy in endometrial carcinoma. Lancet Oncol 13: e353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salvesen HB, Carter SL, Mannelqvist M, Dutt A, Getz G, et al. (2009) Integrated genomic profiling of endometrial carcinoma associates aggressive tumors with indicators of PI3 kinase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 4834–4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, et al. (2010) The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 463: 899–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolfer A, Ramaswamy S (2011) MYC and metastasis. Cancer Res 71: 2034–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. (2006) Identification and validation of oncogenes in liver cancer using an integrative oncogenomic approach. Cell 125: 1253–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ciro M, Prosperini E, Quarto M, Grazini U, Walfridsson J, et al. (2009) ATAD2 is a novel cofactor for MYC, overexpressed and amplified in aggressive tumors. Cancer Res 69: 8491–8498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caron C, Lestrat C, Marsal S, Escoffier E, Curtet S, et al. (2010) Functional characterization of ATAD2 as a new cancer/testis factor and a predictor of poor prognosis in breast and lung cancers. Oncogene 29(37): 5171–5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsia EY, Kalashnikova EV, Revenko AS, Zou JX, Borowsky AD, et al. (2010) Deregulated E2F and the AAA+ coregulator ANCCA drive proto-oncogene ACTR/AIB1 overexpression in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res 8: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stefansson IM, Salvesen HB, Akslen LA (2004) Prognostic impact of alterations in P-cadherin expression and related cell adhesion markers in endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 1242–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zitterbart K, Filkova H, Tomasikova L, Necesalova E, Zambo I, et al. (2011) Low-level copy number changes of MYC genes have a prognostic impact in medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol 102(1): 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meyer N, Penn LZ (2008) Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 976–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zeller KI, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ, O’Donnell KA, Dang CV (2003) An integrated database of genes responsive to the Myc oncogenic transcription factor: identification of direct genomic targets. Genome Biol 4: R69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, et al. (2005) Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102: 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Engelsen IB, Akslen LA, Salvesen HB (2009) Biologic markers in endometrial cancer treatment. APMIS 117: 693–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kalashnikova EV, Revenko AS, Gemo AT, Andrews NP, Tepper CG, et al. (2010) ANCCA/ATAD2 overexpression identifies breast cancer patients with poor prognosis, acting to drive proliferation and survival of triple-negative cells through control of B-Myb and EZH2. Cancer Res 70: 9402–9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stein RA, Chang CY, Kazmin DA, Way J, Schroeder T, et al. (2008) Estrogen-related receptor alpha is critical for the growth of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res 68: 8805–8812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Network TCGAR (2011) Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474: 609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Network TCGAR (2008) Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455: 1061–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rapp UR, Korn C, Ceteci F, Karreman C, Luetkenhaus K, et al. (2009) MYC is a metastasis gene for non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One 4: e6029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zou JX, Revenko AS, Li LB, Gemo AT, Chen HW (2007) ANCCA, an estrogen-regulated AAA+ ATPase coactivator for ERalpha, is required for coregulator occupancy and chromatin modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 18067–18072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwartz BE, Hofer MD, Lemieux ME, Bauer DE, Cameron MJ, et al. (2011) Differentiation of NUT midline carcinoma by epigenomic reprogramming. Cancer Res 71: 2686–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kovacevic Z, Chikhani S, Lovejoy DB, Richardson DR (2011) Novel thiosemicarbazone iron chelators induce up-regulation and phosphorylation of the metastasis suppressor N-myc down-stream regulated gene 1: a new strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Mol Pharmacol 80: 598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vaux DL, Cory S, Adams JM (1988) Bcl-2 gene promotes haemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre-B cells. Nature 335: 440–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurst LD, Pal C, Lercher MJ (2004) The evolutionary dynamics of eukaryotic gene order. Nat Rev Genet 5: 299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma O, Cai WW, Zender L, Dayaram T, Shen J, et al. (2009) MMP13, Birc2 (cIAP1), and Birc3 (cIAP2), amplified on chromosome 9, collaborate with p53 deficiency in mouse osteosarcoma progression. Cancer Res 69: 2559–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, et al. (2010) Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, et al. (2011) BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell 146: 904–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

a) Five additional MYC activation genes sets obtained from the literature and their relative expression in 8q24 amplified versus unamplified samples. b) The correlation between MYC signaling strength and MYC- (left) and ATAD2- (right) gene expression in the primary investigation series and in the internal and external validation series. c) Estrogen receptor negative (ER−) tumors with ATAD2 expression in the top quartile were associated with a high risk of disease-specific death; the risk was much lower among estrogen receptor positive (ER+) tumors with ATAD2 expression in the bottom quartile. d-g) Results from the qPCR validation series. The copy-number of MYC and ATAD2 genes are highly correlated in endometrial cancer (d), glioblastoma (e), ovarian cancer (f) and breast cancer (g).

(EPS)

Details about the shRNA used in the study.

(DOCX)

Names, origins and culture conditions for the cell lines used.

(DOCX)

Patient characteristics and histopathological variables for the endometrial carcinoma series studied.

(DOCX)

Genes in the MYC signaling signature.

(DOCX)

Histopathological variables according to amplification of the 8q24 locus.

(DOCX)

Gene expression of ATAD2 and MYC according to histopathological variables.

(DOCX)

Prediction of ATAD2 gene expression by ATAD2 copy number, ESR1 gene expression and E2F1 gene expression.

(DOCX)

Compounds with gene signatures anticorrelated to metastatic disease or the MYC signaling signature.

(DOCX)

The associations between the sensitivity of 7 endometrial cancer cell lines to MYC knockdown and Tricostatin-A at different concentrations.

(DOCX)