Abstract

There is evidence across several species for genetic control of phenotypic variation of complex traits1–4, such that the variance among phenotypes is genotype dependent. Understanding genetic control of variability is important in evolutionary biology, agricultural selection programmes and human medicine, yet for complex traits, no individual genetic variants associated with variance, as opposed to the mean, have been identified. Here we perform a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of phenotypic variation using 170,000 samples on height and body mass index (BMI) in human populations. We report evidence that the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7202116 at the FTO gene locus, which is known to be associated with obesity (as measured by mean BMI for each rs7202116 genotype)5–7, is also associated with phenotypic variability. We show that the results are not due to scale effects or other artefacts, and find no other experiment-wise significant evidence for effects on variability, either at loci other than FTO for BMI or at any locus for height. The difference in variance for BMI among individuals with opposite homozygous genotypes at the FTO locus is approximately 7%, corresponding to a difference of 0.5 kilograms in the standard deviation of weight. Our results indicate that genetic variants can be discovered that are associated with variability, and that between-person variability in obesity can partly be explained by the genotype at the FTO locus. The results are consistent with reported FTO by environment interactions for BMI8, possibly mediated by DNA methylation9,10. Our BMI results for other SNPs and our height results for all SNPs suggest that most genetic variants, including those that influence mean height or mean BMI, are not associated with phenotypic variance, or that their effects on variability are too small to detect even with samples sizes greater than 100,000.

Genetic studies of complex traits usually focus on quantifying and dissecting phenotypic variation within populations, by contrasting mean differences in phenotypes between genotypes. For example, in association studies the difference between the average phenotype (P) of each genotype is tested. In addition, the phenotypic variance among individuals of the same genotype (G) can vary across genotypes, so that phenotypic variance conditional on genotype, var(P|G), is not constant. Phenotypic variance given a particular genotype does not need to be due to sensitivity to external environmental factors but can, for example, be caused by developmental fluctuation of the internal micro-environment in a genotype-dependent manner1. For example, genetic control of stochastic variation in development or in homeostatic control1,4. The difference between genotypes can also depend on external factors, for example, on the environment in which they are reared, in which case there is a genotype by environment (G × E) interaction. In species in which the same genotype can be measured across defined environments, such as in plant or animal populations, the difference in mean phenotype for each genotype can be quantified experimentally, and is known as the reaction norm of the genotype11,12. However, any environment is likely to be heterogeneous, so that the environment experienced by each individual differs, although these differences are not formally recognized by the experimenter. In this situation, if a G × E interaction exists it may manifest as differences in environmental sensitivity so that genotypes differ in phenotypic variance. Therefore, even if the environments, internal or external, are not directly measured, evidence for genetic control of variation can be quantified through an analysis of variability.

There is empirical evidence for genetic control of phenotypic variation in several species1, including Drosophila13, snails14, maize15 and chickens3, and specific quantitative trait loci with an effect on variance have been reported for yeast2 and Arabidopsis4. Many theories and methods to identify genetic loci responsible for phenotypic variability have been proposed1,16–18. In humans, there have been reports that variability of serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels within monozygotic twin pairs depends on their genotype at the MN blood group system19. In clinical practice, knowledge of phenotypic variability as a function of genotype may be important when the phenotypes are risk factors for disease or treatment response, in particular when there are no mean differences between genotypes in the population19.

Detection of genetic variation in environmental or phenotypic variance requires large sample sizes because relative to their expected values, the variance has a larger sampling error than the mean16,20. We performed a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of phenotypic variation for height and BMI in human populations on approximately 170,000 samples comprising 133,154 in a discovery set and 36,727 for in silico replication, and report a single locus with a genome-wide significant effect on variability in BMI. Height and BMI were chosen because genetic effects on variability in height and size traits have been reported in other species, and because very large samples of genotyped and phenotyped individuals are available through existing research consortia.

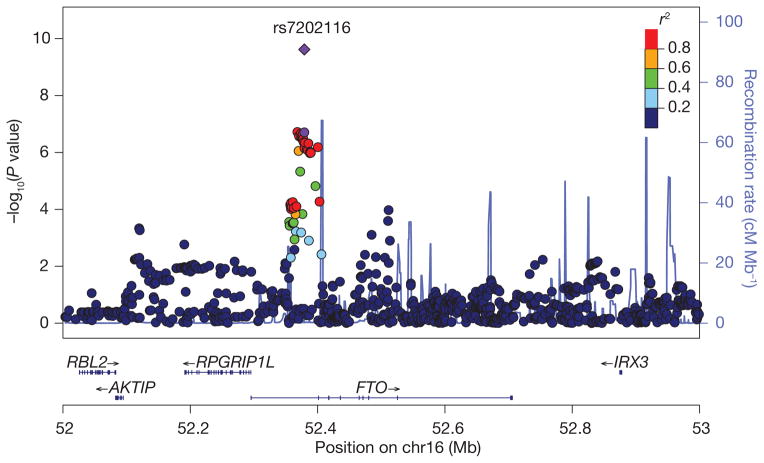

We performed a discovery meta-analysis of 38 studies consisting of 133,154 individuals (60% females) of recent European decent to identify SNPs that are associated with the variability of height or BMI. In each study, ~2.44 million genotyped and imputed autosomal SNPs were included in the analysis after applying quality-control filters. We adjusted height and BMI phenotypes for possible covariates such as age, sex and case-control status, and standardized them to z scores by an inverse-normal transformation. We then regressed the squared z scores (z2), which are a measure of variance20, on the genotype indicator variable of each SNP to test for association of the SNP with trait variability. The association statistics were corrected by the genomic control method21 in individual studies and then combined by an inverse-variance meta-analysis across all of the studies (see Methods). We selected 42 SNPs at 6 loci for height and 51 SNPs at 7 loci for BMI with P < 5 × 10−6 for in silico replication (Supplementary Fig. 1). We examined the top two SNPs at each of the 6 loci for height and 7 loci for BMI in a further sample of 36,727 individuals (54% females) of European ancestry from 13 studies (Methods). For BMI, only rs7202116 at the FTO locus (Fig. 1) and rs7151545 at the RCOR1 locus (Supplementary Fig. 2) were replicated at genome-wide significance level, with P = 2.9 × 10−4 and P = 3.6 × 10−3 in the validation set and P = 2.4 × 10−10 and P = 4.1 × 10−8 in the combined set, respectively (Table 1). None of the height SNPs was replicated (Table 1). We show by an approximate conditional analysis using summary statistics from the discovery meta-analysis and estimated linkage disequilibrium structure from the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) cohort that there is no secondary associated SNP in the FTO region when conditioning on rs7202116 (Supplementary Fig. 3). The estimate of the effect associated with rs7202116 on BMI z2 was slightly larger in men (0.041, standard error (SE) = 0.009) than in women (0.033, SE = 0.007) in the combined set but the difference was not significant (P = 0.670). The RCOR1 SNP only just passed the genome-wide significance level (5 × 10−8), however, it did not reach the experiment-wise significance level (2.5 × 10−8) considering that two independent traits were tested. There were several case-control studies included in the meta-analysis that were ascertained for diseases that may be correlated with BMI. We performed a further meta-analysis in the combined set excluding these case-control studies, and the FTO SNP rs7202116 remained genome-wide significant with P = 2.8 × 10−11 but the RCOR1 SNP did not with P = 3.6 × 10−5 (Supplementary Table 1). We therefore focus on the FTO locus in the main text and provide the results for the RCOR1 locus in the Supplementary Information.

Figure 1. Test statistics (−log10(P values)) for association with BMI variability in the discovery meta-analysis of SNPs at the FTO locus against their physical location.

The SNPs surrounding rs7202116 are colour-coded to reflect their linkage disequilibrium with rs7202116. The recombination rates are plotted in cyan to reflect local linkage disequilibrium structure. Genes, the position of exons and the direction of transcription from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser are noted. The P value for rs7202116 in the combined set is represented by a purple diamond, and that from the discovery set by a purple circle.

Table 1.

Associations of the top 6 and 7 loci with variance of height and BMI, respectively

| Chr. | SNP | bp | Nearest gene | CA | Discovery

|

In silico replication

|

Combined

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | β | SE | P | n | Freq. | β | SE | P | n | β | SE | P | n | |||||

| Height | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | rs6429820 | 14,210,915 | PRDM2 | G | 0.196 | −0.035 | 0.0071 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 129,200 | 0.209 | −0.002 | 0.0131 | 8.9 × 10−1 | 32,355 | −0.027 | 0.0062 | 1.0 × 10−5 | 161,555 |

| 2 | rs6429975 | 143,002,110 | KYNU | T | 0.180 | −0.036 | 0.0074 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 129,196 | 0.177 | −0.002 | 0.0137 | 8.9 × 10−1 | 32,472 | −0.028 | 0.0065 | 1.0 × 10−5 | 161,668 |

| 2 | rs6748377 | 45,002,877 | SIX3 | T | 0.175 | −0.038 | 0.0075 | 4.0 × 10−7 | 129,183 | 0.185 | −0.006 | 0.0138 | 6.7 × 10−1 | 31,988 | −0.031 | 0.0066 | 3.0 × 10−6 | 161,171 |

| 7 | rs10486722 | 41,778,433 | INHBA | C | 0.339 | 0.029 | 0.0060 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 128,834 | 0.318 | −0.005 | 0.0112 | 6.3 × 10−1 | 32,416 | 0.021 | 0.0053 | 6.0 × 10−5 | 161,250 |

| 8 | rs1026852 | 3,577,500 | CSMD1 | G | 0.444 | −0.029 | 0.0059 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 126,363 | 0.435 | −0.004 | 0.0110 | 7.4 × 10−1 | 31,837 | −0.023 | 0.0052 | 7.0 × 10−6 | 158,200 |

| 14 | rs12891343 | 34,453,301 | BAZ1A | T | 0.227 | 0.031 | 0.0068 | 5.0 × 10−6 | 128,725 | 0.225 | 0.012 | 0.0120 | 3.2 × 10−1 | 36,150 | 0.027 | 0.0059 | 6.0 × 10−6 | 164,875 |

| BMI | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | rs12328474 | 140,638,570 | LRP1B | G | 0.263 | −0.038 | 0.0078 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 104,640 | 0.250 | 0.035 | 0.0152 | 2.0 × 10−2 | 32,403 | −0.023 | 0.0069 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 137,043 |

| 2 | rs10932241 | 208,685,200 | CRYGD | C | 0.407 | 0.028 | 0.0059 | 2.9 × 10−6 | 127,597 | 0.411 | −0.006 | 0.0125 | 6.2 × 10−1 | 28,641 | 0.022 | 0.0053 | 5.6 × 10−5 | 156,238 |

| 4 | rs11942401 | 188,052,244 | FAT | A | 0.140 | −0.043 | 0.0085 | 4.3 × 10−7 | 125,010 | 0.128 | 0.003 | 0.0187 | 8.5 × 10−1 | 28,016 | −0.035 | 0.0077 | 6.2 × 10−6 | 153,026 |

| 6 | rs1418304 | 82,795,837 | IBTK | G | 0.496 | −0.026 | 0.0057 | 3.3 × 10−6 | 127,611 | 0.493 | 0.004 | 0.0103 | 6.9 × 10−1 | 36,721 | −0.019 | 0.0050 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 164,332 |

| 14 | rs12894649 | 102,232,512 | RCOR1 | C | 0.057 | 0.061 | 0.0126 | 1.3 × 10−6 | 127,080 | 0.050 | 0.058 | 0.0248 | 1.9 × 10−2 | 32,298 | 0.060 | 0.0112 | 7.9 × 10−8 | 159,378 |

| 14 | rs7151545 | 102,247,397 | RCOR1 | G | 0.057 | 0.059 | 0.0126 | 2.4 × 10−6 | 127,080 | 0.053 | 0.083 | 0.0285 | 3.6 × 10−3 | 28,040 | 0.063 | 0.0115 | 4.1 × 10−8 | 155,120 |

| 16 | rs7193144 | 52,368,187 | FTO | C | 0.403 | 0.030 | 0.0058 | 1.9 × 10−7 | 127,537 | 0.406 | 0.020 | 0.0115 | 8.0 × 10−2 | 32,449 | 0.028 | 0.0052 | 5.4 × 10−8 | 159,986 |

| 16 | rs7202116 | 52,379,116 | FTO | G | 0.402 | 0.035 | 0.0067 | 2.0 × 10−7 | 95,966 | 0.417 | 0.039 | 0.0107 | 2.9 × 10−4 | 35,267 | 0.036 | 0.0057 | 2.4 × 10−10 | 131,233 |

| 18 | rs620052 | 37,900,962 | PIK3C3 | G | 0.378 | 0.033 | 0.0069 | 1.6 × 10−6 | 95,971 | 0.382 | −0.010 | 0.0111 | 3.7 × 10−1 | 34,668 | 0.021 | 0.0059 | 3.5 × 10−4 | 130,639 |

The squared z scores (z2) were used to test for association of the top 6 and 7 SNPs with trait variability (height and BMI, respectively). The discovery set consists of 133,154 individuals, and data for in silico replication are from another 36,727 samples. At both the FTO and RCOR1 loci, the second top SNPs (highlighted in bold) in the discovery set pass the single trait genome-wide significance level (5 × 10−8) in the combined set. β, estimate of additive effect on z2; bp, physical position; CA, coded allele; chr., chromosome; freq., frequency of the coded allele.

On the scale on which BMI is measured, the predicted perallele effect of the G allele (the other allele is A) of rs7202116 on the mean difference is 0.37 kg m−2 in men and 0.43 kg m−2 in women22, and the effect on the variance difference is 0.79 kg2 m−4 in men and 1.09 kg2 m−4 in women, reflecting the larger standard deviation of BMI in women compared with men (Supplementary Table 2). Assuming an additive model, the mean difference between the GG and AA genotypes is 0.74 kg m−2 in men and 0.86 kg m−2 in women, with a variance difference between the two genotypes of 1.58 kg2 m−4 in men and 2.18 kg2 m−4 in women, which is 7.2% of the phenotypic variance of BMI in both men and women. To provide an illustration of the effect of rs7202116 on BMI variance, we did an approximate calculation of its effect on the variance of weight. If we take the mean height of 1.78 m for men and 1.65 m for women, the difference in the variance of weight between the two genotype groups is roughly 16 kg2 in both men and women (Supplementary Table 2). For example, if the standard deviation (SD) of weight is 15 kg for men, the predicted SD of weight in the two homozygous genotype classes is 14.73 and 15.27 kg, respectively.

The effect of a SNP on variance could be owing to our use of the z2 value as a measure of variance or to a general relationship between mean and variance of BMI1,23. Below we present evidence that excludes these two explanations.

If an SNP has an effect on the mean, the test statistic for association of the SNP with z2 will be inflated, and the non-centrality parameter (NCPv0) of the χ2 test under the null hypothesis of no effect on variance is: np(1 −p)(1 −2p)2(a +(1 −2p)d)4, in which n is the sample size, p is the frequency of the coded allele, and a and d are the additive and dominance effects, respectively, on the mean difference (Supplementary Note). We show by analysis and simulation results based on an additive and dominance genetic model that such inflation is inversely proportional to the minor allele frequency (MAF) of the SNP; that is, SNPs with a lower MAF will tend to have higher test statistics under the null hypothesis (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, when we plotted the observed test statistics of the confirmed 180 height loci24 and 32 BMI loci22 that have the largest reported effects on the mean, we did not observe such a trend (Supplementary Fig. 5). We calculated the NCPv0 of the known height and BMI loci given the effects on the mean from the published papers22,24, and the NCPv0 values of all these known loci were smaller than 1 (results not shown). The observed genomic inflation factor in the discovery meta-analysis was 1.039 for height and 1.033 for BMI (Supplementary Fig. 6). This small inflation could be due to many SNPs affecting the mean and therefore having a tiny effect on z2 (Supplementary Fig. 7), or many SNPs that have an effect on the variance that is too small to be significant even with our large sample size. Across common SNPs in the genome, variants at the FTO locus have the largest effect size on BMI22. The G allele of the FTO SNP rs7202116 has a population frequency of ~0.4 and an additive effect on the mean BMI of ~0.1 z-score units5,22. If our significant result at the FTO locus is due only to an allelic effect on mean BMI, we would expect an allelic effect on variability of ~0.002 (predicted from the equation in the Supplementary Note), which is very small compared with the observed effect of 0.036. For some traits, the variance changes in a predictable manner as the mean changes. In this case, a scale transformation, such as a logarithmic transformation, can remove effects on the variance when they are simply due to an effect on the mean1. We were interested in effects of SNP on variability that would remain after a scale transformation, and therefore sought to exclude scale effects that could explain our observed association. We performed further analyses in three data sets each with approximately 20,000 individuals with individual-level genotype and phenotype data available to verify the effects of rs7202116 at the FTO locus on BMI variance (Methods and Table 2). We used several tests, including Bartlett’s test statistic, to test for the difference in variance between the three genotypes. The Bartlett’s test P value was <0.05 in each of the three data sets, regardless of whether or not the BMI phenotypes were adjusted for the mean difference, logarithm transformed or inverse-normal transformed (Table 2). In the combined analysis of the three data sets totalling 60,624 individuals, the effect of rs7202116 on the BMI z2 score after adjusting for the mean difference was 0.030 (P = 1.2 × 10−4) for inverse-normal transformed BMI, 0.065 (2.3 × 10−12) for logarithm-transformed BMI, and 0.097 (8.9 × 10−16) for BMI without scale transformation (Table 2). The decrease of the effect of rs7202116 on BMI z2 owing to the adjustment of the mean difference was ~0.003, in line with that of ~0.002 as predicted from the theory above. Similar conclusions as above can be drawn from the further analyses for rs7151545 at the RCOR1 locus (Supplementary Table 3). We plotted the test statistics and estimates for the effects on the variability in our discovery meta-analysis against those for the effects on the mean from the published GIANT meta-analyses for height24 and BMI22, and did not find any apparent correlations except for a few outlying SNPs at the FTO locus (Supplementary Fig. 7). These results together suggest that the observed effect of the FTO SNP on variability is neither a consequence of the effect on the mean nor due to the choice of scale, and that our inverse-normal transformation is likely to be overly conservative. Results from reported quantile regression of untransformed BMI on a multiple SNP predictor of BMI and on FTO25 are consistent with our results but are also consistent with scale effects due to the skewed distribution of untransformed BMI. We have shown in this study that the effect of FTO on variability is not due to a scale effect and, concordantly, a quantile regression of both transformed and untransformed BMI z-scores on the SNPs at the FTO and RCOR1 loci on BMI on 17,974 individuals shows a relationship between effect size and the quantile of the distribution (Supplementary Fig. 8). By contrast, the use of untransformed BMI induces widespread correlation between estimated SNP effects on the mean and on variance (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Table 2.

Effects of the FTO SNP rs7202116 on BMI

| BMI

|

log(BMI)

|

BMI (inv. norm.)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadj. | Adj. | Unadj. | Adj. | Unadj. | Adj. | |

| WGHS (n = 22,888) | ||||||

| β | 0.148 | 0.142 | 0.100 | 0.093 | 0.046 | 0.040 |

| SE | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| P | 4.5 × 10−13 | 4.0 × 10−12 | 5.5 × 10−11 | 8.6 × 10−10 | 6.8 × 10−4 | 3.3 × 10−3 |

| Permutation P | <1 × 10−4 | <1 × 10−4 | <1 × 10−4 | <1 × 10−4 | 9.0 × 10−4 | 3.9 × 10−3 |

| Bartlett’s P | 1.1 × 10−24 | 1.1 × 10−24 | 2.0 × 10−11 | 2.0 × 10−11 | 6.5 × 10−3 | 6.6 × 10−3 |

| Mean AA | −0.070 | 0.0 | −0.069 | 0.0 | −0.068 | 0.0 |

| Mean AG | −0.001 | 0.0 | −0.001 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mean GG | 0.161 | 0.0 | 0.159 | 0.0 | 0.152 | 0.0 |

| Variance AA | 0.895 | 0.900 | 0.932 | 0.937 | 0.971 | 0.977 |

| Variance AG | 1.002 | 1.008 | 0.995 | 1.001 | 0.990 | 0.996 |

| Variance GG | 1.194 | 1.202 | 1.132 | 1.138 | 1.060 | 1.066 |

| EPIC (n = 19,762) | ||||||

| β | 0.077 | 0.076 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.027 | 0.026 |

| SE | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| P | 1.7 × 10−4 | 2.1 × 10−4 | 3.2 × 10−3 | 3.9 × 10−3 | 6.1 × 10−2 | 7.1 × 10−2 |

| Permutation P | <1 × 10−4 | <1 × 10−4 | 4.9 × 10−3 | 5.1 × 10−3 | 6.4 × 10−2 | 7.1 × 10−2 |

| Bartlett’s P | 7.6 × 10−7 | 7.6 × 10−7 | 3.0 × 10−3 | 3.0 × 10−3 | 1.2 × 10−1 | 1.2 × 10−1 |

| Mean AA | −0.077 | 0.000 | −0.076 | 0.000 | −0.075 | 0.000 |

| Mean AG | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 |

| Mean GG | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.000 | 0.100 | 0.000 |

| Variance AA | 0.932 | 0.936 | 0.951 | 0.955 | 0.967 | 0.970 |

| Variance AG | 1.005 | 1.009 | 1.007 | 1.011 | 1.010 | 1.013 |

| Variance GG | 1.085 | 1.089 | 1.045 | 1.049 | 1.013 | 1.017 |

| ARIC + QIMR + NHS + HPFS (n = 17,974) | ||||||

| β | 0.070 | 0.067 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.026 | 0.024 |

| SE | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| P | 1.7 × 10−3 | 2.8 × 10−3 | 3.6 × 10−3 | 6.1 × 10−3 | 8.9 × 10−2 | 1.2 × 10−1 |

| Permutation P | 1.6 × 10−3 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 3.8 × 10−3 | 7.1 × 10−3 | 8.7 × 10−2 | 1.2 × 10−1 |

| Bartlett’s P | 1.2 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 2.5 × 10−4 | 2.5 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−2 | 2.0 × 10−2 |

| Mean AA | −0.067 | 0.0 | −0.068 | 0.0 | −0.069 | 0.0 |

| Mean AG | 0.006 | 0.0 | 0.008 | 0.0 | 0.010 | 0.0 |

| Mean GG | 0.122 | 0.0 | 0.118 | 0.0 | 0.113 | 0.0 |

| Variance AA | 0.968 | 0.973 | 0.978 | 0.983 | 0.994 | 0.998 |

| Variance AG | 0.968 | 0.972 | 0.974 | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.979 |

| Variance GG | 1.131 | 1.136 | 1.093 | 1.097 | 1.059 | 1.064 |

| Combined (n = 60,624) | ||||||

| β | 0.100 | 0.097 | 0.068 | 0.065 | 0.034 | 0.030 |

| SE | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| P | 8.9 × 10−17 | 8.9 × 10−16 | 1.4 × 10−13 | 2.3 × 10−12 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−4 |

| Bartlett’s P | 1.3 × 10−32 | 1.3 × 10−32 | 8.5 × 10−15 | 8.6 × 10−15 | 4.4 × 10−4 | 4.2 × 10−4 |

| Mean AA | −0.071 | 0.0 | −0.071 | 0.0 | −0.070 | 0.0 |

| Mean AG | 0.005 | 0.0 | 0.006 | 0.0 | 0.007 | 0.0 |

| Mean GG | 0.129 | 0.0 | 0.127 | 0.0 | 0.122 | 0.0 |

| Variance AA | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Variance AG | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| Variance GG | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.05 |

The effects of the FTO SNP rs7202116 on the variance for BMI and log(BMI) were tested in three subsets of data. The BMI phenotypes were corrected for age effect and standardized to z scores using the mean and standard deviation, or by an inverse-normal (inv. norm.) transformation in each gender group in each cohort. Phenotypes were adjusted (adj.) (or unadjusted (unadj.)) for mean difference in the three genotypes. For the EPIC cohort, 2,397 samples were in the meta-analysis, and 17,376 were not part of the meta-analysis. For the combined ARIC, QIMR, NHS and HPFS cohort, 12,741 samples were in the meta-analysis and 5,233 samples were not. β, the effect of the G allele on z2; Bartlett’s P, P value calculated from the Bartlett’s test for variance difference in the three genotypes; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; permutation P, empirical P value calculated from 10,000 permutations; QIMR, Queensland Institute of Medical Research; WGHS, Women’s Genome Health Study.

We have reported a meta-analysis of GWAS of squared normalized residuals for two quantitative traits in human populations, and provide empirical evidence that the FTO and RCOR1 loci influence phenotypic variance of obesity. Conversely, we did not observe any significant SNPs for height or any significant SNPs other than those at the FTO and RCOR1 loci for BMI to be genome-wide significantly associated with phenotypic variance (Table 1), even for those loci known to have effects on the mean (Supplementary Fig. 5), which indicates that SNP effects on variance are uncommon for height and BMI, and those previously identified SNP effects on the mean, although very small, are robust to environmental perturbation. We provide evidence that the association between the FTO locus and BMI variability is not due to artefacts such as scale or ascertainment. We also discuss that it is implausible that the observed effect of the FTO SNP on variance is due to its strong linkage disequilibrium (D′ = 1) with a causal variant that has a large effect on the mean (Supplementary Note). The FTO SNPs that are associated with variance are also associated with mean differences in BMI. Interestingly, this phenomenon seems to be restricted to the FTO gene and to obesity, because we did not observe such effects for height or for BMI at loci other than FTO. One possible explanation of the observation is a differential response to physical activity26, because interactions between FTO genotypes and physical activity have been reported for the same SNPs as we report in this study: the G allele that is associated with an increase in mean BMI has a smaller effect in the group of people with a high level of physical activity than in the absence of physical activity8,27,28. There may be other unknown lifestyle factors, including diet, that also interact with the FTO genotype and result in the observed effect on variability.

We do not provide a mechanism of how alleles at FTO influence variability (how FTO alleles affect the mean is also not known). However, the fact that the allele that increases obesity also increases variability suggests a breakdown of homeostatic control. Data on mice lacking the Fto gene suggest that the observed effects on mean obesity in humans may be due to upregulation or dysregulation of FTO expression, resulting in an increased susceptibility to obesity29. If both upregulation and impairment of FTO expression have a role then this could provide a mechanism of the observed effect on variability. The FTO protein affects demethylation of nuclear RNA in vitro29, but whether the efficiency of this process depends on the FTO genotype or how this may be related to the observed effects on BMI is not clear. Notably, a recent study reported that rs7202116 allele G, which is present on the obesity-susceptibility haplotype at the FTO locus, creates a CpG site along with other variants in perfect linkage disequilibrium with it9, and therefore risk alleles have increased DNA methylation. In addition, it was reported that a CpG site in the first intron of FTO showed significant hypomethylation in type 2 diabetes cases relative to controls30, and that the risk variant seems to have an effect on methylation status at other genes10. DNA methylation can be affected by environmental influences, including dietary and lifestyle factors, and may affect gene expression. For example, physical exercise may increase gene expression at the FTO locus, but less so in GG individuals compared with AA individuals because their alleles are more methylated. This therefore suggests a possible mechanism for the observed effects on both the mean and variability. However, more research is needed to determine the molecular effect and mechanism of FTO on both the levels and variability of obesity.

Overall, our findings are consistent with a low heritability of phenotypic variability1 and no common genetic variants that account for a large proportion of variation in environmental or phenotypic variability. They also indicate an absence of widespread genotype-by-environment interaction effects, at least for height and obesity in humans and with interaction effects large enough to be detected in our study in which specific environmental factors were not identified. Nevertheless, the demonstration that individual genetic loci with effects on variability can be identified with sufficiently large sample sizes facilitates further study to understand the function and evolution of the genetic control of variation.

METHODS

Fifty-one studies were included in the meta-analysis. All individuals were of recent European descent. In each of the participating studies, genotyped SNPs that passed standard quality-control processes (missingness, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test and MAF) were used to impute the ungenotyped SNPs to the HapMap II CEU reference panel31. We excluded SNPs with imputation quality score <0.4 for IMPUTE32 and <0.3 otherwise33,34. A summary of sample size, genotyping platform, quality-control filters and the imputation tool of all the participating studies is provided in Supplementary Table 4. We further excluded SNPs with MAF < 0.01 in each study or in the meta-analysis, and retained about 2.68 million autosomal SNPs in the analysis.

In each study, height and BMI phenotypes were adjusted for age and standardized to z score by an inverse-normal transformation. The analysis protocol supplied to all cohorts is given as a Supplementary Note. The descriptive statistics of phenotypes of each study are shown in Supplementary Table 5. The association analyses of phenotypic variability were performed on a single-SNP basis by the following additive genetic model: y = α +βx +e, in which y is z2, α is the intercept, β is the additive SNPeffect on z2, x is the allelic dosage coded as 0, 1 or 2 for the three genotype groups, and e is the residual. We stratified the analysis by gender group and/or case-control status where applicable. We selected 38 studies consisting of 133,154 individuals as the discovery set by the time when data were available. We collected summary-level association results of all the SNPs from these studies and adjusted the standard errors of all SNPs by the genomic control approach in each study21, that is, multiplying the standard errors of the estimates of β by the square root of the genomic inflation factor21. We then combined the effect of each SNP by an inverse-variance meta-analysis implemented in METAL35. In a regression analysis, the squared standard error of the estimate of a SNP effect is: σ2/(2p(1 −p)n), in which σ2 is the residual variance, p is the frequency of the coded allele, and n is the sample size. This assumes Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of genotype frequencies. If the effect size is small, σ2 is approximately equal to the variance of y, which is 2. We checkedthe overall quality of each study by plotting the median of 1/SEacross all SNPs against thereported sample size, and by plotting the median of 2p(1 −p)nSE2 across all SNPs to see if it was close to 2 (Supplementary Fig. 10). We further estimated the effective sample size of each SNP by: ñ = 2/(2p(1 − p)SE2), using the summary statistics of the whole discovery set, and excluded SNPs with ñ < mean(ñ) −2SD(ñ) and retained ~2.44 million SNPs for both height and BMI. We collected data from a further 36,727 samples from 13 cohorts (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), and validated the top SNPs at 6 associated loci for height and 7 for BMI (P < 5 × 10−6) in these extra samples.

We performed further analyses in three data sets with a total sample size of 60,624 with individual-level genotype and phenotype data to verify our findings. These three data sets include 22,888 individuals from the WGHS cohort, and 19,762 individuals from the EPIC cohorts, and a combined sample of 17,974 individuals from the ARIC, QIMR, NHS and HPFS cohorts, with 17,365 individuals from the EPIC cohort and 5,233 individuals from the NHS and HPFS cohorts not part of the meta-analysis. We used logarithm or inverse-normal transformation to remove a possible mean–variance relationship of BMI phenotypes, and adjusted the phenotype for the effect of the top SNP at the FTO or RCOR1 locus on the mean of BMI. We performed permutation tests to assess the significance of the effect of FTO or RCOR1 on BMI z2 with 10,000 permutations, and used the Bartlett’s statistic to test for difference in variance of BMI between three genotypes for FTO or RCOR.

The plot of association results at the FTO locus in Fig. 1 was generated using LocusZoom36 with the recombination rates and pairwise linkage disequilibrium r2 values between SNPs estimated from the HapMap CEU panel31.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC grants 241944, 389875, 389891, 389892, 389938, 442915, 442981, 496739, 496688, 552485, 613672, 613601 and 1011506), the US National Institutes of Health (grants AA07535, AA10248, AA014041, AA13320, AA13321, AA13326, DA12854 and GM057091) and the Australian Research Council (ARC grant DP1093502). A detailed list of acknowledgements by study is provided in the Supplementary Information. We apologize to authors whose work we could not cite owing to space restrictions.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions P.M.V., M.E.G. and J.Y. conceived and designed the study. J.Y. and P.M.V. derived the analytical theory. J.Y. performed the meta-analyses and simulations. J.Y. and P.M.V. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J.Y., D.I.C., J.H.Z. and R.J.F.L. performed further statistical verification analyses. D.P.S., W.G.H., R.J.F.L., S.I.B. and H. Snieder contributed important additional concepts and critically reviewed the manuscript before submission. S.E.M., P.A.F.M., A.C.H., N.G.M., D.R.N. and G.W.M. contributed the individual-level genotype and phenotype data of the QIMR cohort. T.M.F., J.N.H. and R.J.F.L. liaised with the GIANT consortium for this project. The cohort-specific contributions of all other authors are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Hill WG, Mulder HA. Genetic analysis of environmental variation. Genet Res. 2010;92:381–395. doi: 10.1017/S0016672310000546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansel J, et al. Cell-to-cell stochastic variation in gene expression is a complex genetic trait. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolc A, White IM, Avendano S, Hill WG. Genetic variability in residual variation of body weight and conformation scores in broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2009;88:1156–1161. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimenez-Gomez JM, Corwin JA, Joseph B, Maloof JN, Kliebenstein DJ. Genomic analysis of QTLs and genes altering natural variation in stochastic noise. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frayling TM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dina C, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nature Genet. 2007;39:724–726. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scuteri A, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilpeläinen TO, et al. Physical activity attenuates the influence of FTO variants on obesity risk: a meta-analysis of 218,166 adults and 19,268 children. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell CG, et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis identifies haplotype-specific methylation in the FTO type 2 diabetes and obesity susceptibility locus. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almén MS, et al. Genome wide analysis reveals association of a FTO gene variant with epigenetic changes. Genomics. 2012;99:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falconer DS. Selection in different environments: effects on environmental sensitivity (reaction norm) and on mean performance. Genet Res. 1990;56:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jinks JL, Connolly V. Selection for specific and general response to environmental differences. Heredity. 1973;30:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackay TF, Lyman RF. Drosophila bristles and the nature of quantitative genetic variation. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2005;360:1513–1527. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ros M, et al. Evidence for genetic control of adult weight plasticity in the snail Helix aspersa. Genetics. 2004;168:2089–2097. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ordas B, Malvar RA, Hill WG. Genetic variation and quantitative trait loci associated with developmental stability and the environmental correlation between traits in maize. Genet Res. 2008;90:385–395. doi: 10.1017/S0016672308009762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Christensen OF, Sorensen D. Use of genomic models to study genetic control of environmental variance. Genet Res. 2011;93:125–138. doi: 10.1017/S0016672311000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rönnegård L, Valdar W. Detecting major genetic loci controlling phenotypic variability in experimental crosses. Genetics. 2011;188:435–447. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paré G, Cook NR, Ridker PM, Chasman DI. On the use of variance per genotype as a tool to identify quantitative trait interaction effects: a report from the Women’s Genome Health Study. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin NG, Rowell DM, Whitfield JB. Do the MN and Jk systems influence environmental variability in serum lipid levels? Clin Genet. 1983;24:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1983.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visscher PM, Posthuma D. Statistical power to detect genetic loci affecting environmental sensitivity. Behav Genet. 2010;40:728–733. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nature Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Struchalin MV, Dehghan A, Witteman JC, van Duijn C, Aulchenko YS. Variance heterogeneity analysis for detection of potentially interacting genetic loci: method and its limitations. BMC Genet. 2010;11:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lango Allen H, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams PT. Quantile-specific penetrance of genes affecting lipoproteins, adiposity and height. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e28764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silventoinen K, et al. Modification effects of physical activity and protein intake on heritability of body size and composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1096–1103. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreasen CH, et al. Low physical activity accentuates the effect of the FTO rs9939609 polymorphism on body fat accumulation. Diabetes. 2008;57:95–101. doi: 10.2337/db07-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rampersaud E, et al. Physical activity and the association of common FTO gene variants with body mass index and obesity. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1791–1797. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia G, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nature Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toperoff G, et al. Genome-wide survey reveals predisposing diabetes type 2-related DNA methylation variations in human peripheral blood. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:371–383. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The International HapMap Consortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genom × 10−wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nature Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pruim RJ, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.