Abstract

Purpose

Trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer is highly efficacious yet costly and time-intensive, and few data are available about its utilization. We examined receipt and completion of adjuvant trastuzumab by race/ethnicity and education for women with HER2-positive disease.

Methods

Using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Breast Cancer Outcomes Database, we identified 1,109 women diagnosed with stage I–III, HER2-positive breast cancer during September 2005 through December 2008 who were followed for ≥1 year. We assessed the association of race/ethnicity and education with receipt of trastuzumab, and among women who initiated trastuzumab, with completion of >270 days of therapy, using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

The cohort was 75% white, 8% black, and 9% Hispanic; 20% attained a high school degree or less. Most women (83%) received trastuzumab, with no significant differences by race/ethnicity or SES. Among women initiating trastuzumab, 73% of black women vs. 87% of white women (p=.007) and 70% of women with less than high school education vs. 90% of women with a college degree completed >270 days of therapy (p=.006). In adjusted analyses, black (vs. white) women and those without a high school degree (vs. college degree) had lower odds of completing therapy (odds ratio [OR]=.45, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.27–.74 and OR=0.27, 95% CI=.14–.51, respectively).

Conclusion

We observed differences in trastuzumab completion by race and educational attainment for women treated at NCCN centers. Efforts to assure appropriate utilization of trastuzumab and understand treatment barriers are needed and could lead to improved outcomes.

Keywords: breast cancer, disparities, trastuzumab, race, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is an important mediator of cell proliferation and differentiation.1,2 Although HER2-positive breast cancers have traditionally had poor prognoses,3 the natural history of this disease subtype changed dramatically with the development and widespread use of trastuzumab. Since June 2005, adjuvant treatment guidelines have recommended that standard chemotherapy be supplemented with trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive cancers4 after large-scale randomized trials demonstrated a disease recurrence risk of approximately 0.50 compared with chemotherapy alone, with few adverse events.5–7 Trastuzumab administration involves a 30–90 minute infusion administered weekly or every 3 weeks for one year, with an estimated total cost of more than $100,000 when trastuzumab is incorporated into anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens.8

Previous research has demonstrated disparities in receipt of adjuvant therapies, including radiation and endocrine therapy for black woman compared with white women.9–12 In addition, black women experience worse breast cancer outcomes than white women, even when matched for known prognostic factors.13 Although the reasons for racial disparities in outcomes are multifactorial, differences in receipt of efficacious treatments likely contribute. Differences in receipt of breast cancer care and outcomes by socioeconomic status (SES) have also been observed,14–18 although studying associations of treatment and outcomes with SES is often reliant on area-level measures of education and income.

Although trastuzumab has substantially improved outcomes for women with HER2-positive breast cancer, a risk for disparity has arisen because of the high cost and time-intensive commitment required for therapy. Identification of potential treatment differences for women with HER2-positive breast cancer is crucial, yet few data are available about the use of trastuzumab. We examined disparities in the receipt and completion of adjuvant trastuzumab in a large cohort of women treated in National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) centers across the U.S.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Source

Since 1997, the NCCN Breast Cancer Outcomes Database Project has evaluated patterns and outcomes of cancer care.19 It prospectively captures information on patient and tumor characteristics, treatments, and outcomes abstracted from patients, medical records, and institutional systems for women with breast cancer treated at member institutions.20–22 Patients were included in the database if they received all or some of their treatment at a reporting center; those with one time consultations were not included. Eight centers contributed data to this analysis: City of Hope National Medical Center; University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; Fox Chase Cancer Center; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Roswell Park Cancer Institute; H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center; University of Michigan Cancer Center; and Ohio State University. NCCN data include information abstracted from medical records on age, HER2, other tumor characteristics, comorbidity, and treatments received, as well as patient-reported information on race/ethnicity, educational attainment, insurance, and employment. Data collected by the NCCN are subject to rigorous quality assurance and routine on-site audits of source documents against submitted data.

Study Cohorts

We identified two study cohorts. We examined receipt (i.e., initiation) of trastuzumab in cohort 1 and completion of trastuzumab therapy in cohort 2. Cohort 1 included adult women with a first diagnosis of stage I–III breast cancer that over-expressed HER2, defined as a ‘positive’ result by fluorescence in situ hybridization or a score of 3+, ‘high positive’, or ‘positive not otherwise specified’ by immunohistochemistry. We restricted this cohort to 1,145 women who were diagnosed with breast cancer during September of 2005 through December of 2008 with follow-up data through December of 2009. After excluding 36 women with <365 days of follow-up at the reporting institution, the first cohort included 1,109 women.

For the second cohort, we focused on the 925 women from cohort 1 who initiated any trastuzumab. We excluded 17 patients with a break in their trastuzumab regimen of >30 days (because of uncertainty in interpreting reasons for treatment break), 2 women who had 0 days of trastuzumab documented, and 18 women who stopped trastuzumab for progression, transfer of care, or death. Cohort 2 included 888 women.

Variables of Interest

Our dependent variables of interest were (a) receipt of neo/adjuvant trastuzumab for the first cohort and (b) completion of adjuvant trastuzumab for the second cohort. Receipt of trastuzumab was defined as having a reported start date for trastuzumab at any time after diagnosis but before any recurrence. Completion of trastuzumab was defined as documented receipt of >270 days of treatment, calculated by summing the duration of all trastuzumab treatments received in the neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant setting (this considers all women who received ≥75% of the recommended 1 year of trastuzumab therapy to have completed therapy). For the 62 women who did not have an end date documented for trastuzumab, we used the date of last follow-up with medical oncology at the NCCN institution as a proxy for the end date. Using this definition, 59/62 women were categorized as having completed trastuzumab and 3/62 were defined as not having completed trastuzumab.

Our independent variables of interest were race/ethnicity and education. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander/other. We defined education as college/postgraduate degree, some college/junior college, high school graduate, less than high school graduate, and unknown.

Additional independent variables at diagnosis (categorized as in Table 1) included age, employment, insurance, comorbidity (based on Charlson and Katz scoring systems23, 24 from medical records and patient surveys), institution (blinded, labeled AH), diagnosis year, disease stage, tumor grade, and hormone receptor status.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by race/ethnicity in cohort 1

| Characteristic (no. of patients, %) | Overall (N=1,109) | White (n=837) | Black (n=93) | Hispanic (n=103) | Asian/Pacific Islander/Other (n=76) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | .17 | |||||

| <50 | 496 (45) | 363 (43) | 38 (41) | 52 (50) | 43 (57) | |

| 50–59 | 325 (29) | 241 (29) | 32 (34) | 29 (28) | 23 (30) | |

| 60–69 | 183 (17) | 147 (18) | 13 (14) | 16 (16) | 7 (9) | |

| ≥ 70 | 105 (9) | 86 (10) | 10 (11) | 6 (6) | 3 (4) | |

| Education | <.0001 | |||||

| College/graduate degree | 404 (36) | 314 (38) | 26 (28) | 28 (27) | 36 (47) | |

| Some college | 218 (20) | 165 (20) | 28 (30) | 18 (17) | 7 (9) | |

| High school degree | 161 (15) | 118 (14) | 12 (13) | 22 (21) | 9 (12) | |

| Less than high school | 54 (5) | 24 (3) | 6 (6) | 21 (20) | 3 (4) | |

| Other/unknown | 272 (25) | 216 (26) | 21 (23) | 14 (14) | 21 (28) | |

| Employment | <.0001 | |||||

| Employed/student | 577 (52) | 444 (53) | 46 (49) | 51 (50) | 36 (47) | |

| Homemaker | 178 (16) | 130 (16) | 6 (6) | 30 (29) | 12 (16) | |

| Unemployed | 69 (6) | 36 (4) | 15 (16) | 12 (12) | 6 (8) | |

| Retired | 153 (14) | 125 (15) | 18 (19) | 6 (6) | 4 (5) | |

| Other/unknown | 132 (12) | 102 (12) | 8 (9) | 4 (4) | 18 (24) | |

| Insurance | NE‡ | |||||

| Managed | 784 (71) | 615 (73) | 57 (61) | 60 (58) | 52 (68) | |

| Indemnity | 34 (3) | 30 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | |

| Medicaid/indigent/self-pay | 107 (10) | 45 (5) | 16 (17) | 31 (30) | 15 (20) | |

| Medicare | 167 (15) | 134 (16) | 17 (18) | 11 (11) | 5 (7) | |

| Other/unknown | 17 (2) | 13 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Comorbidity | NE‡ | |||||

| 0 | 913 (82) | 695 (83) | 76 (82) | 77 (75) | 65 (86) | |

| 1 | 148 (13) | 105 (13) | 14 (15) | 21 (20) | 8 (11) | |

| 2+ | 48 (4) | 37 (4) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) | 3 (4) | |

| Year of diagnosis | .21 | |||||

| 2005 | 115 (10) | 93 (11) | 8 (9) | 8 (8) | 6 (8) | |

| 2006 | 399 (36) | 296 (35) | 40 (43) | 41 (40) | 22 (29) | |

| 2007 | 383 (35) | 285 (34) | 33 (35) | 39 (38) | 26 (34) | |

| 2008 | 212 (19) | 163 (19) | 12 (13) | 15 (15) | 22 (29) | |

| Stage | .24 | |||||

| I | 422 (38) | 326 (39) | 30 (32) | 34 (33) | 32 (42) | |

| II | 418 (38) | 322 (38) | 37 (40) | 36 (35) | 23 (30) | |

| III | 269 (24) | 189 (23) | 26 (28) | 33 (32) | 21 (28) | |

| Tumor grade | NE‡ | |||||

| High | 749 (68) | 549 (66) | 68 (73) | 80 (78) | 52 (68) | |

| Low/intermediate | 325 (29) | 258 (31) | 22 (24) | 21 (20) | 24 (32) | |

| Unknown | 35 (3) | 30 (4) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Hormone receptor status¥ | .03 | |||||

| Positive | 684 (62) | 304 (36) | 41 (44) | 40 (39) | 40 (53) | |

| Negative | 425 (38) | 533 (64) | 52 (56) | 63 (61) | 36 (47) |

P-values calculated by chi-square testing for characteristics associated with race/ethnicity

Not estimable (NE) due to small cell counts

Defined as positive if estrogen receptor-positive or progesterone receptor-positive. Defined as negative if estrogen receptor-negative or progesterone receptor-negative, and neither are positive.

Statistical Analysis

We compared rates of trastuzumab receipt and completion by race/ethnicity, education, and other patient characteristics using individual χ2 tests. We used two logistic regression models to assess the probability of (a) receipt of trastuzumab and (b) completion of trastuzumab by race/ethnicity and education, adjusting for the independent variables listed above. We used generalized estimating equations to account for clustering at the institutional level.

We performed multiple sensitivity analyses for cohort 2. First, we repeated analyses restricting to stage II–III patients because most of the adjuvant clinical trials with trastuzumab included higher-risk patients, and some stage I patients may be treated differently. Second, we repeated analyses after re-defining completion of trastuzumab as receipt of ≥350 days of treatment among patients with ≥18 months of follow-up. Third, because 59/62 women without documented treatment end dates were defined as having completed trastuzumab, we repeated analyses after assuming all 62 of these women did not complete therapy. Lastly, because development of cardiotoxicity impacts treatment, we repeated models with inclusion of a binary variable for anthracycline receipt.

All p-values are two-sided and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Because analyses used previously collected data without identifying patient information, the study was considered exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

RESULTS

Patient and tumor characteristics for cohort 1 are presented in Table 1. Most women were white (75%), 8% were black, 9% were Hispanic, and 7% were Asian/Pacific Islander/other race/ethnicity. Approximately 36% of women completed college/graduate school, while 20% of women attained a high school degree or less. There were no significant differences in age, comorbidity, diagnosis year, stage, or tumor grade by race/ethnicity, although white women had the highest percentage of hormone receptor-negative cancers. Overall, white women and those of Asian/Pacific Islander/other race had higher educational attainment than black and Hispanic women. White women were most likely to be insured by managed care, while black, Hispanic, and Asian/other women had higher rates of Medicaid/indigent/self-pay coverage.

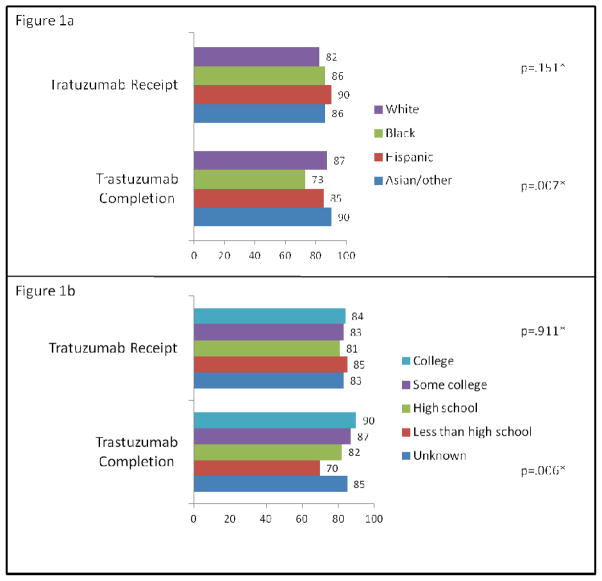

Among the 1,109 women in cohort 1, 83% initiated trastuzumab. Unadjusted rates of trastuzumab receipt did not differ by race/ethnicity (range 82–90%, p=.151) (Figure 1a) or education (range 81–85%, p=.91) (Figure 1b). In adjusted analyses, we did not observe racial/ethnic or education differences in treatment initiation (Table 2). With regard to other variables, women aged ≥70 (vs. <50), those with highest comorbidity (vs. lowest), and those with lower/intermediate (vs. higher) grade tumors had lower odds of treatment receipt, while women diagnosed in 2006–2008 (vs. 2005) and those with stage II–III disease (vs. stage I) had higher odds of treatment receipt. Compared with the reference institution, all but one institution had lower odds of trastuzumab initiation (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted percents of trastuzumab receipt and completion by race/ethnicity (1a) and by education (1b)

*Overall p-values by chi-square testing

Table 2.

Unadjusted proportions and adjusted odds for receipt and completion of trastuzumab

| Variable | N (%) receiving trastuzumab N=1,109 | Unadjusted p-value┼ | Adjusted OR for receipt of trastuzumab (95% CI)* | N (%)completing trastuzumab N=888 | Unadjusted p-value┼ | Adjusted OR for completion of trastuzumab (95% CI) among women initiating treatment* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | .151 | .007 | ||||

| White | 687 (82) | 1.00 | 576 (87) | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 80 (86) | 1.02 (.65,1.59) | 53 (73) | .45 (.27,.74) | ||

| Hispanic | 93 (90) | 1.40 (.86,2.28) | 76 (85) | 1.40 (.79,2.48) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander/Other | 65 (86) | 1.06 (.44,2.54) | 57 (90) | 1.78 (.99,3.21) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | <.0001 | .022 | ||||

| <50 | 445 (90) | 1.00 | 372 (88) | 1.00 | ||

| 50–59 | 278 (86) | .75 (.39,1.44) | 226 (85) | .79 (.57,1.10) | ||

| 60–69 | 145 (79) | .60 (.36,1.01) | 124 (88) | 1.12 (.42,3.01) | ||

| ≥70 | 57 (54) | .18 (.08,.39) | 40 (73) | .58 (.13,2.52) | ||

| Education | .911 | .006 | ||||

| College/graduate degree | 341 (84) | 1.00 | 294 (90) | 1.00 | ||

| Some college | 182 (83) | .94 (.67,1.32) | 151 (87) | .71 (.37,1.34) | ||

| HS degree | 131 (81) | .84 (.58,1.23) | 102 (82) | .50 (.33,.77) | ||

| Less than HS degree | 46 (85) | 1.58 (.98,2.52) | 31 (70) | .27 (.14,.51) | ||

| Other/unknown | 225 (83) | 1.54 (.62,3.85) | 184 (85) | .72 (.38,1.36) | ||

| Employment | .002 | .492 | ||||

| Employed/student | 491 (85) | 1.00 | 415 (88) | 1.00 | ||

| Homemaker | 148 (83) | .89 (.69,1.15) | 114 (83) | .79 (.53,1.17) | ||

| Unemployed | 61 (88) | 1.11 (.56,2.21) | 49 (86) | 1.30 (.36,4.78) | ||

| Retired | 110 (72) | 1.37 (.96,1.94) | 87 (81) | .89 (.32,2.48) | ||

| Other/unknown | 115 (87) | 1.82 (.50,6.69) | 97 (87) | 1.27 (.48,3.32) | ||

| Insurance | <.0001 | .502 | ||||

| Managed | 682 (87) | 1.00 | 571 (87) | 1.00 | ||

| Indemnity | 28 (82) | .78 (.32,1.88) | 20 (80) | .85 (.44,1.65) | ||

| Medicaid/indigent | 81 (90) | .74 (.41,1.36) | 64 (83) | .99 (.62,1.59) | ||

| Self-pay | 13 (76) | .42 (.17,1.05) | 11 (85) | .75 (.29,1.99) | ||

| Medicare | 107 (64) | .59 (.32,1.06) | 84 (81) | .89 (.34,2.35) | ||

| Other/unknown | 14 (82) | .78 (.18,3.40) | 12 (86) | .53 (.24,1.15) | ||

| Comorbidity | .0008 | .112 | ||||

| 0 | 779 (85) | 1.00 | 648 (86) | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 112 (76) | .77 (.51–1.16) | 89 (86) | 1.27 (.69,2.34) | ||

| 2+ | 34 (71) | .50 (.26,.97) | 25 (74) | .60 (.28,1.28) | ||

| Year of diagnosis | .012 | .803 | ||||

| 2005 | 84 (73) | 1.00 | 68 (85) | 1.00 | ||

| 2006 | 343 (86) | 2.28 (1.20,4.32) | 282 (85) | 1.08 (.58,1.99) | ||

| 2007 | 322 (84) | 2.12 (1.32,3.41) | 257 (86) | 1.21 (.63,2.35) | ||

| 2008 | 176 (83) | 2.40 (1.08,5.32) | 155 (88) | 1.20 (.61,2.34) | ||

| Stage | <.0001 | .040 | ||||

| I | 287 (68) | 1.00 | 247 (89) | 1.00 | ||

| II | 384 (92) | 4.98 (3.95,6.29) | 319 (86) | .76 (.46,1.27) | ||

| III | 254 (94) | 6.77 (4.77,9.60) | 196 (82) | .64 (.34,1.21) | ||

| Tumor grade | <.0001 | .586 | ||||

| High | 659 (88) | 1.00 | 545 (86) | 1.00 | ||

| Low/intermediate | 242 (75) | .49 (.29,.82) | 197 (84) | .71 (.35,1.43) | ||

| Unknown | 24 (69) | .38 (.21,.68) | 20 (91) | 1.71 (.70,4.19) | ||

| Hormone receptor status¥ | .0007 | .052 | ||||

| Positive | 550 (80) | .80 (.56,1.14) | 463 (88) | 1.41 (.75,2.66) | ||

| Negative | 375 (88) | 1.00 | 299 (83) | 1.00 | ||

| Institution** | .0008 | .008 | ||||

| A | -- (90) | 1.00 | -- (82) | 1.00 | ||

| B | -- (85) | .82 (.70,.98) | -- (83) | 1.09 (.80,1.48) | ||

| C | -- (79) | .58 (.49,.69) | -- (90) | 1.45 (1.24,1.70) | ||

| D | -- (78) | .57 (.35,.93) | -- (89) | 1.79 (1.36,2.37) | ||

| E | -- (72) | .46 (.37,.56) | -- (87) | 1.74 (1.38,2.20) | ||

| F | -- (84) | .62 (.40,.95) | -- (77) | .63 (.46,.88) | ||

| G | -- (85) | .91 (.73,1.14) | -- (92) | 2.78 (2.29,3.39) | ||

| H | -- (85) | .70 (.59,.84) | -- (94) | 2.95 (2.42,3.60) |

Differences in unadjusted percents of receipt and completion of treatment were examined using chi-square testing

Using generalized estimating equations accounting for clustering at institution level, adjusting for treating center and all variables in the table

Defined as positive if estrogen receptor-positive or progesterone receptor-positive. Defined as negative if estrogen receptor-negative or progesterone receptor-negative, and neither are positive.

Institutions are de-identified for this analysis and sample sizes are not provided

Abbreviations: OR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, HS = high school

Among the 888 women in cohort 2, 86% completed ≥270 days of treatment with a median treatment duration of 350 days (range 2–1,261). The rates of treatment completion were lowest for black women compared with other women (Figure 1a) and for women with less than a high school education (Figure 1b). In adjusted analyses (Table 2), black women had significantly lower odds of completing trastuzumab compared with white women (odds ratio [OR]=.45; 95% confidence interval [CI]=.27–.74). In addition, we observed differences in therapy completion by education; women without a high school diploma and those with a high school diploma but no college education had lower odds of completion compared with those who with a college degree (OR=.27, 95% CI=.14–.51 and OR=.50, 95% CI=.33–.77, respectively). We observed no differences in odds of trastuzumab completion for women in cohort 2 by age, comorbidity, diagnosis year, stage, or tumor grade but did observe institutional variation with 5 centers having higher odds, 1 center having lower odds, and 1 center having similar odds of completing therapy compared with the reference institution (Table 2).

In a sensitivity analysis for the second cohort after restriction to patients with stage II–III disease (n=612), results for race/ethnicity and education were similar to the initial model (OR=.45, 95% CI=.23–.90, for black vs. white women and OR=.27, 95%=CI .14–.51, for less than high school education vs. college degree). In an analysis restricted to patients with 18 months of follow-up (n=731) with trastuzumab completion defined as treatment for >350 days, black women had persistently lower odds of completion compared with white women (OR=.47, 95% CI=.31–.72), although the findings for education were no longer statistically significant (OR for less than high school education=1.12, 95% CI=.62–2.02; OR for high school diploma=.86, 95% CI=.64–1.16; both vs. college degree). In the model categorizing the 62 women without a completion date as having not completed trastuzumab, results were also similar to the original analysis (data not shown). Finally, in the model with the anthracycline variable, the findings for race and education were unchanged (data not shown). Employment was not significant in any of the models performed.

DISCUSSION

We examined use of trastuzumab, an efficacious yet costly and time-intensive treatment, by race/ethnicity and education in a large cohort of women with HER2-positive breast cancer who were treated at NCCN centers across the U.S. We observed no disparities in initiation of trastuzumab by race/ethnicity and education but found differences in treatment completion, with black women and those with lower educational attainment having significantly lower odds of therapy completion compared with white and college-educated women. Our findings were robust to multiple sensitivity analyses. To our knowledge, this analysis represents the first examination of differences in trastuzumab utilization.

Given the substantial improvement in outcomes from receipt of trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancers, the overall high rates of receipt and completion of therapy were reassuring, suggesting substantial agreement with treatment recommendations among practicing oncologists.4 Moreover, despite the burden of ongoing infusional treatments, 86% of women initiating trastuzumab completed 270 days of therapy. This is higher than estimates of completing standard infusional chemotherapy among patients initiating adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer, where studies have shown variable 6-month completion rates of 58–78%, with lower rates of completion among older patients and those with greater comorbidity.25–27 Nevertheless, despite the relatively high rates of trastuzumab completion in our analysis, the disparities we observed raise concerns. Although it is possible that patients may still benefit from shorter durations of trastuzumab,28 this has not been well studied, and guidelines recommend one year of therapy for all patients.4

Possible explanations for the differences in rates of treatment completion include toxicity, variable patient preferences, institutional variations in toxicity assessments, and provider and patient adherence, which may be amplified by the need for frequent infusions over a prolonged period. Previous studies have suggested that black women may have an increased risk for cardiotoxicity with anthracycline chemotherapy,29–32 although detailed toxicity assessments for minority patients receiving trastuzumab have not been reported. Lower adherence has also been reported for non-white women and those of lower SES initiating adjuvant hormonal therapy,33–35 where five years of adjuvant therapy is recommended.4 Barriers to long term adherence, including patient/family preferences to discontinue therapy early, may be particularly relevant for women of lower socioeconomic status, who may have more difficulty freeing themselves from work and childcare commitments. Although we observed lower odds of treatment completion for those who did not graduate high school, we did not find differences in completion of treatment by employment. However, this may result from our inability to distinguish types of jobs among employed women. We also did not observe differences in receipt or completion of treatment by insurance, suggesting broad insurance coverage for trastuzumab. Notably, our cohort reflected a group who had sought care at a NCCN center, and had very few patients without insurance.

Although specific barriers to completion of care could not be elucidated in our study, our results suggest that the development of interventions may be necessary to assure completion of therapy for women who do not experience serious toxicity. Because of the need to continuously calculate the number of trastuzumab infusions a patient has received, enhanced electronic medical records with provider reminders for a patient’s expected end date of therapy could help to assure that all doses are delivered. Strategies may also focus on patient adherence, with patient reminders and/or provider alerts if a patient misses an infusion appointment. Enhanced patient education about the benefits of trastuzumab and the expected duration of therapy may be particularly useful for those with lower educational attainment.

We observed lower rates of treatment receipt for women with lower risk cancers, older age, and those with greater comorbidity. These findings were not surprising given the uncertainty about the optimal systemic treatment strategy for lower-risk disease and concerns about toxicity, competing risk, or perceived lower benefits of treatment in older and sicker populations. Although trastuzumab is well tolerated in most women, it is initially administered with chemotherapy. Consequently, decisions to treat older and sicker women are likely based on concerns about tolerance of chemotherapy rather than trastuzumab. Other studies have demonstrated lower rates of adjuvant chemotherapy for older women with breast cancer,36,37 but few data are available regarding the rates of trastuzumab receipt for women of varying ages.38,39 Among women who initiated trastuzumab in our study, we observed no differences in odds of completing therapy by age or comorbidity; thus, providers may be selecting patients to receive treatment who will optimally tolerate it.

The strengths of this analysis include our ability to examine detailed information on receipt of infusional treatments for a large cohort of women with information on HER2-status and individualized information on employment and education, which are not currently available in other cancer registries. However, we acknowledge several limitations. First, the care patterns in NCCN centers may not be generalizable to other settings and the numbers of minority women were relatively small. Nevertheless, assessment of care at academic centers is of interest. Second, although NCCN data on trastuzumab duration may be imperfect, our findings were robust to sensitivity analyses and rigorous data quality checks. Third, detailed information on why trastuzumab was stopped was not available, nor did analyses account for other factors that could influence treatment, such as and social supports, marital status, or distance to the medical center. Finally, because of the small numbers of women in some sub-groups (i.e. employment, insurance), we may have had insufficient power to detect small differences in the outcomes of interest.

In conclusion, we observed differences in completion by race and education but not initial receipt of adjuvant trastuzumab. Further work is needed to better understand differences in adherence, reasons for premature cessation, and differences in tolerance to therapy. With the expected substantial improvement in outcomes for women who receive one year of adjuvant trastuzumab, improved and appropriate administration of this agent could have a significant impact on disease recurrence and survival for women with HER2-positive breast cancer. Interventions aimed at assuring receipt of guideline care for all women with HER2-positive breast cancers should be a priority.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: Funded in part by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation and Grant P50 CA89393 from the National Cancer Institute to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, et al. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature. 2003;421(6924):756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarden Y. The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. Signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 (Suppl 4):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–82. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [Accessed March 13, 2012];Breast Cancer. V.I.2012. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf/

- 5.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1659–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1673–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slamon DJ, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing doxurubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (ACT) with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and trastuzumab (AC TH) with docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab (TCH) in HER2-positive early breast cancer patients: BCIRG 006 study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94(suppl):S5a. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurian AW, Thompson RN, Gaw AF, Arai S, Ortiz R, Garber AM. A cost-effectiveness analysis of adjuvant trastuzumab regimens in early HER2/neu-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6):634–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1357–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman RA, He Y, Winer EP, Keating NL. Trends in racial and age disparities in definitive local therapy of early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):713–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund MJ, Brawley OP, Ward KC, Young JL, Gabram SS, Eley JW. Parity and disparity in first course treatment of invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;109:545–57. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Stevens JL. Racial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under age 35. Cancer. 2003;97(1):134–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jatoi I, Anderson WF, Rao SR, Devesa SS. Breast cancer trends among black and white women in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7836–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu XC, Lund MJ, Kimmick GG, et al. Influence of race, insurance, socioeconomic status, and hospital type on receipt of guideline-concordant adjuvant systemic therapy for locoregional breast cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(2):142–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2522–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):490–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhargava A, Du XL. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in adjuvant chemotherapy for older women with lymph node-positive, operable breast cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(13):2999–3008. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Gangnon RE, et al. Socioeconomic status and survival after an invasive breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2011;117(7):1542–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed July 10, 2011];NCCN Oncology Outcomes Database Project. http://www.nccn.org/network/business_insights/outcomes_database/outcomes.asp.

- 20.Weeks JC. Outcomes assessment in the NCCN. Oncology (Williston Park) 1997;11(11A):137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weeks J. Outcomes assessment in the NCCN: 1998 update. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Oncology (Williston Park) 1999;13(5A):69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niland JC. NCCN outcomes research database: data collection via the Internet. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14(11A):100–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobie SA, Baldwin LM, Dominitz JA, Matthews B, Billingsley K, Barlow W. Completion of therapy by Medicare patients with stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(9):610–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibbs P, McLaughlin S, Skinner I, et al. Re: Completion of therapy by Medicare patients with stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(21):1582. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neugut AI, Matasar M, Wang X, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and survival among the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2368–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):809–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krischer JP, Epstein S, Cuthbertson DD, Goorin AM, Epstein ML, Lipshultz SE. Clinical cardiotoxicity following anthracycline treatment for childhood cancer: the Pediatric Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(4):1544–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasan S, Dinh K, Lombardo F, Kark J. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(2):196–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grenier MA, Lipshultz SE. Epidemiology of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in children and adults. Semin Oncol. 1998;25(4 Suppl 10):72–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snider JN, SA, Paba C, et al. Cardiotoxicity of Trastuzumab Treatment in African American Women and Older Women in the Non Trial Setting. Presented at the 2009 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 12, 2009; p. Abstract #5087. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):602–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedin T, Guo C, Nattinger A. Persistence with adjuvant hormone therapy in older breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol; Presented at the 2011 American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting; Chicago, IL. 2011. p. abstr 6032. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2750–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elkin EB, Hurria A, Mitra N, Schrag D, Panageas KS. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2757–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidman A, Hudis C, Pierri MK, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in the trastuzumab clinical trials experience. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1215–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrano C, Cortes J, De Mattos-Arruda L, et al. Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity in the elderly: a role for cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]