Abstract

Objective

To examine the possibility that maintenance cognitive behavior therapy (M–CBT) may improve the likelihood of sustained improvement and reduced relapse in a multi-site randomized controlled clinical trial of patients who met criteria for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.

Method

Participants were all patients (N = 379) who first began an open trial of acute-phase CBT. Patients completing and responding to acute-phase treatment were randomized to receive either nine monthly sessions of M-CBT (n = 79) or assessment only (n = 78) and were then followed for an additional 12 months without treatment.

Results

M–CBT produced significantly lower relapse rates (5.2%) and reduced work and social impairment compared to the assessment only condition (18.4%) at a 21-month follow-up (MFU). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models showed that residual symptoms of agoraphobia at the end of acute-phase treatment were independently predictive of time to relapse during 21-MFU (HR = 1.15, p < .01).

Conclusions

M–CBT aimed at reinforcing acute treatment gains to prevent relapse and offset disorder recurrence may improve long-term outcome in PD/A.

Keywords: maintenance treatment, treatment outcome, panic disorder, randomized controlled clinical trial, cognitive behavior therapy

Panic disorder (PD) is associated with significant personal, social, and economic costs. PD is prevalent (Kessler et al., 2005), reduces quality of life (Mendlowicz & Stein, 2000), and ranks among the most expensive psychiatric disorders (Batelaan et al., 2007). The clinical course of PD has been characterized as chronic, with high rates of relapse, particularly for women (Katschnig et al., 1995; Keller et al., 1994; Yonkers, Bruce, Dyck, & Keller, 2003). It is well-established that pharmacological treatments show higher rates of PD recurrence following treatment discontinuation (25% to 85%) (Mavissakalian & Perel, 1992; Otto, Pollack, & Sabatino, 1996; Rickels & Schweizer, 1998) compared to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), (Haby, Donnelly, Corry, & Vos, 1996; Norton & Price, 2007). Despite encouraging data supporting the relative durability of CBT, many patients drop out, relapse, or fail to achieve strong treatment response (Barlow, Gorman, Shear, & Woods, 2000; Haby, et al., 1996). For this reason, strategies to maintain treatment gains and prevent recurrence over the longer term are of clinical importance.

CBT is an effective treatment for panic disorder with and without agoraphobia (PD/A) (Craske & Barlow, 2008; McHugh, Smits, & Otto, 2009). Results of randomized controlled trials indicate that 50% to 80% of patients with PD/A show a clinically significant improvement in response to CBT (Aaronson et al., 2008; Ost, Thulin, & Ramnerö, 2004; Schmidt et al., 2000), and this improvement is relatively durable. For example, in a large multi-site clinical trial (Barlow, et al., 2000), the effects of CBT alone were more enduring than medication treatments at 6 month follow up, a finding mirroring earlier analyses (Gould, Otto, & Pollack, 1995). The available data show that 5% to 30% of patients who attain successful acute-phase remission status will relapse in the one to two years following CBT discontinuation (Clark et al., 1994; Heldt et al., 2011; van Apeldoorn et al., 2010). However, as encouraging as those data are, single cross-sectional follow-up assessments necessarily underestimate the presence of infrequent panics and other fluctuating PD symptoms.

Data from longitudinal CBT follow-up studies support this contention. For example, a follow-up study of patients with PD/A treated with CBT found that most patients had a fluctuating post-treatment course (Brown & Barlow, 1995). Although 75% of patients were panic-free at 24-month follow-up, only 21% met criteria for high end–state functioning at both 3 and 24 months post-treatment and were panic-free for the year preceding the 24-month assessment. It is also noteworthy that this sample by definition suffered from no more than mild agoraphobia at pretreatment. Similar results were reported by Burns and colleagues for agoraphobic patients treated with in vivo exposure therapy (Burns, Thorpe, & Cavallaro, 1985). In that study, participants as a group evidenced continued improvement at assessment points up to 8 years post-treatment, but longitudinal evaluations showed that their clinical courses were characterized by periods of setback. Thus, studies that follow patients over the long-term to examine the durability of treatment response and the timing of relapse are important.

One of the most positive, although uncontrolled, studies of the long-term effects of psychological treatment for PD was conducted by Fava et al. (1995) on 110 patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia (PDA) who were treated with in vivo exposure therapy emphasizing self-directed practice. In that study, 81 participants achieved remission, defined as being panic free for the past month and “much better” on a global measure of improvement (Fava, Zielezny, Savron, & Grandi, 1995). Survival analysis estimated the likelihood of staying in remission at 2, 5, and 7 years post-treatment to be 96%, 77%, and 67%, respectively (projected remission rates of 71%, 57%, and 49% for the intention-to-treat sample). Although these numbers are good, several points bear consideration. First, the sample was a consecutive series of patients meeting DSM-III-R criteria for PDA, including low as well as high levels of agoraphobic avoidance. Many participants who were classified as responders still had some residual agoraphobic avoidance. Among those, two-thirds relapsed within 5 years. The presence of residual agoraphobia at the end of behavioral treatment is associated with relapse over time and this finding has been replicated in other studies (Dow et al., 2007). This robust finding informed the rationale for this study examining long-term strategies for PD/A. In addition in the Fava et al., study, benzodiazepine use was permitted and a sizable proportion of patients (one-fourth at the conclusion of treatment) were taking benzodiazepines. Finally, the survival data are based on cross-sectional assessments that, as noted earlier, substantially overestimate remission rates.

A major limitation of naturalistic studies is that they do not involve prospectively planned maintenance treatment. Some do report on intervening treatment, and most patients are found to receive it. However, there is little information about the quantity or quality of such treatment. For example, in the Brown and Barlow (1995) 2-year follow-up study of PD/A patients treated with CBT, 33% of the sample had sought additional treatment during the follow-up interval, 23% specifically for panic attacks. Based on their study with treatment completers, 27% sought additional treatment due to a less-than-adequate response to initial treatment. All of these findings indicate a need for clinical methods to sustain acute treatment response and prevent relapse over time for patients with PD/A.

In this collaborative follow-up study, we developed a maintenance CBT (M–CBT) and tested its efficacy as a long-term strategy for the management of PD/A among responders to three months of acute treatment. The two primary aims in this paper are: 1) To examine whether nine months of monthly M–CBT significantly improved the likelihood of sustained improvement among patients who responded to acute-phase CBT during those nine months as well as for the following 12 months (21 months total) compared to an assessment only group over the same period, and 2) To examine clinical predictors associated with loss-of-response (i.e., relapse) compared to maintenance of response (i.e., survival) over a 21-month follow-up among patients who responded to acute-phase CBT. For patients who respond to acute-phase CBT, examining if M–CBT (i.e., strategies) sustains acute gains over time may have useful clinical implications. In this study, the predictors examined at the end of acute CBT on time to relapse during the follow-up period included time, randomized group assignment, age, sex, extent of clinical global improvement, panic disorder severity, and agoraphobia severity. Demographic factors (i.e., age, sex) were tested for any differential effects across condition, and clinical predictors were examined for sustained improvement across global (i.e., clinical global improvement) and specific measures (i.e., panic disorder severity). We also examined agoraphobia symptoms based on evidence showing that residual agoraphobia is linked with loss of response following acute CBT. We examined these aims in a multi-site randomized controlled clinical trial of patients with PD/A. This study extends past research by examining treatment-response in a detailed fashion over a relatively long follow-up of 21-months in a study sufficiently powered to answer questions about maintenance strategies and in the investigation of the probability of remaining relapse-free across a number of clinical predictors for PD/A.

Method

Participants

A total of 379 patients were recruited in a multi-site clinical trial examining long-term strategies for the treatment for PD/A at four sites, Boston, New York, New Haven, and Pittsburgh. Patients completed a baseline diagnostic interview and were enrolled in the study at one of these four clinical sites. Inclusion criteria were: (a) a principal DSM-IV diagnosis of PD/A; (b) age 18 years or older; (c) no substance abuse or dependence within the last 6 months; (d) absence of active suicide potential within the last 6 months; (e) absence of any history of psychosis, bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, or cyclothymia; (f) no current application pending or existing for a medical disability claim; (g) no significant cognitive impairment; (h) free from current uncontrolled general medical illness requiring intervention; (i) absence of concurrent psychotherapeutic treatment directed at anxiety or panic disorders and; (j) no concurrent psychopharmacological treatment that may have anti-panic effects (participants on anxiolytic medications were required to discontinue medication/s by session 9). A total of 256 patients completed the acute phase of the study and post-treatment diagnostic interview and assessment. For additional description and results from the acute phase of the clinical trial, please see Aaronson and colleagues (2008). In sum, the Acute CBT consisted of a modified version of Panic Control Treatment (Barlow & Craske, 2007; Craske & Barlow, 2007) delivered in 11-sessions and covered psychoeducation on the nature of anxiety and panic, identification and correction of maladaptive thoughts about anxiety and its consequences, and interoceptive and situational exposure exercises. Some modifications included an earlier introduction of interoceptive exposure, the elimination of breathing retraining except as an optional procedure chosen by therapists for a small minority of patients to examine hyperventilatory tendencies rather than as a strategy for reducing anxiety, and an earlier introduction of paired interoceptive and situation exposure practices.

This study examines only 168 patients (65%) who were classified as Acute CBT responders. The 88 patients who did not meet criteria for responder were assigned to the non-responder arm of the long term strategies for treating PD/A trial (Payne, et al., 2012). The criteria for Acute CBT treatment response (see p. 16-17 for definition of treatment response) were purposely stringent to ensure that a sufficient number of individuals would be classified into the second-stage study (i.e., acute CBT responders; acute CBT non-responders). Nevertheless, the acute treatment response rate was comparable to our previous multi-site clinical trial (Barlow, et al., 2000). Of the 168 patients who met criteria for responder, 11 were either not willing (e.g., moving) or did not qualify due to study protocol violations (e.g., filing a claim for medical disability) to be randomized resulting in a randomized sample of 157 responders. Patients were randomized to one of two groups, either M–CBT (n = 79) or Assessment Only condition (n = 78). Of the patients randomized to M–CBT, three randomized patients did not enter treatment. We included data on all 157 randomized participants as the intent to treat sample. Study inclusion and exclusion for the randomization study were, of course, identical to the criteria for the acute phase of the study since those patients were continued on to randomization. At randomization, all patients were reminded of and agreed to adhere to initial study enrollment criteria from the acute phase including the absence of concurrent psychotherapeutic treatment directed at anxiety or panic disorders and no concurrent psychopharmacological treatment that may have anti-panic effects (e.g., SSRIs, benzodiazepines). Responders were followed for a total of 21 months following acute phase CBT, and IEs who were blinded to patients’ progress in the study conducted all assessments. IEs continued to assess for concurrent drug or psychotherapeutic treatment throughout the study.

Therapists and Treatment

Therapists

Sixteen therapists administered the M–CBT. Therapists were experienced clinicians trained and supervised in the M–CBT protocol by personnel at the Boston site. All therapists were either doctoral-level clinicians (Ph.D. or graduate level clinicians-in-training). Therapists were aged 22–52 years (M = 37.8, SD = 10) and reported 0.6 to 20 years of experience with CBT (M = 6.1, SD = 5.1). They were 43% male, and most identified themselves as cognitive-behavioral (85%) or psychodynamic (10%) in orientation. In all but one case, the M–CBT therapist was the same one who conducted the patient’s Acute CBT treatment.

Training included didactic instruction, hour-for-hour supervision of at least two training cases, and group supervision meetings during which both specific application and general issues of the treatment protocol were discussed. All M–CBT sessions were audiotaped, and sessions were independently evaluated and rated by trained and certified adherence raters for adherence and compliance with the M–CBT treatment manual and other characteristics of treatment delivery (e.g., therapist use of Socratic questioning, patient homework compliance, and rapport). Site coordinators and therapists were provided with results of the Adherence and Competence ratings in the cases in which therapists did not adhere achieve high ratings (i.e., non-adherent session, low competence rating). The therapist then underwent additional training and received additional supervision before another case was assigned.

Maintenance CBT (M–CBT)

The aims of M–CBT were to: 1) encourage continued practice and application of the acute CBT treatment skills; and 2) teach relapse prevention strategies including distinguishing normal symptom fluctuations from “lapses” and “relapse,” anticipating and responding constructively to symptom exacerbations, improving stress management skills, and examining the costs of recovery.

All sessions were conducted according to an unpublished M–CBT Therapist treatment protocol (Spiegel & Baker, 1999) written and developed for this research study. Patient treatment sessions were delivered according to the protocol and were tailored to individual patient needs. As noted above, all patients in this study met a high threshold for response criteria at the post-acute assessment although a few patients were still experiencing some mild symptoms. One aim of M–CBT was to encourage continued practice of acute CBT treatment skills. For example, for patients with residual anxiety related to panic and somatic sensations, continued work on cognitive restructuring skills and interoceptive exposure was emphasized. For patients with residual or reemerging agoraphobic avoidance, continued situational exposure was encouraged. Patients were urged to re-read portions of the acute treatment client workbook, based on an earlier version of (Barlow & Craske, 2007), during M–CBT as applicable. A second aim of M– CBT was to teach relapse prevention strategies. For example, patients were taught the distinctions between normal symptom fluctuations and “lapses” and “relapse”. Identifying any unrealistic or worrisome thoughts about the extent or durability of his/her improvement in the months ahead, normalizing and challenging patient’s thoughts as appropriate, decatastrophizing symptom increases, and assisting the patient establish a plan to cope with symptom increases. The goal was to help patients act as their own therapist when confronted with symptom increases or a situation that may put them at increased risk for slips. A session on costs of recovery encouraged patients to consider possible disadvantages of improvement (e.g., increased social expectations, more work responsibility, less time alone). Home practice was assigned to accompany each monthly session.

Maintenance treatment consisted of nine monthly, 45–60 minute sessions delivered in individual therapy sessions. Sessions were delivered with a minimum of 14 days between sessions to allow patients’ time to complete assigned home practices, and sessions were delivered within +/− 14 days from their nominal monthly dates. Sessions were allowed to be skipped; however, patients who did not complete at least 6 of 9 sessions were removed from the study.

Measures

Independent-Evaluator (IE) Certification and Measures

Training and Certification

IEs at the four sites included extensively trained bachelor-level staff, advanced psychology students, a registered nurse (RN), and masters-level and PhD-level clinicians who underwent a rigorous training and certification procedure under the direction of the Pittsburgh site to ensure standardization of administration and diagnostic reliability. Many evaluators who were previously trained on the ADIS for DSM-IV-Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L), who received additional training under the direction of the Principal Investigator at the Pittsburgh site. All evaluators who were not already certified on the ADIS-IV-L, attended a one-day didactic workshop with the PI in which all measures and procedures used in the study were reviewed, including the ADIS-Lite.

For certification as an IE, trainees were required to conduct two certification interviews and meet the following criteria: 1) match with the trainer on the primary diagnosis; 2) agree within one point on the ADIS-Lite Clinical Severity Rating (CSR); (3) agree within 5 points on the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scales, with not more than one point difference on any one scale item; (4) agree within one point on the Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) Scale rating; and (5) agree within 3 points on the PDSS total score; with not more than one point difference on any one item. IEs were blind to patients’ progress in the study.

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Lite (ADIS-Lite)

The ADIS-Lite is an adaptation of the ADIS-IV-L, a semi–structured clinical interview assessing anxiety, mood, substance use, and somatoform disorders that has demonstrated excellent to acceptable interrater reliability for the anxiety and mood disorders (Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994). The primary adaptation is the assessment of symptoms within each diagnosis as present/absent rather than as a dimensional rating (0–8) in the ADIS-IV-L.

Ten percent of all assessments were randomly selected for diagnostic co-rating by assessment supervisors at the Pittsburgh site. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to examine interrater reliability for the clinician-rated ADIS-Lite diagnoses and CSRs (N = 164) across the independently conducted clinical interviews. Ratings from primary interviewers (IEs) were compared with those of secondary raters. Interrater reliability was mostly acceptable across the diagnoses (panic disorder, ICC = 0.89, agoraphobia, ICC = 0.66, major depressive disorder ICC = 0.10, generalized anxiety disorder, ICC = 0.10, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ICC = 0.75, social phobia, ICC = 0.91, specific phobia, ICC = 0.80, dysthymia, ICC = 0.50, and posttraumatic stress disorder, ICC = 0.49).

ADIS-Agoraphobia Scale (Ag Scale)

IEs rated panic-related phobic avoidance of 21 common situations (e.g., theaters, public transportation). Scores range from 0 (no avoidance) to 4 (extreme avoidance). This measure has demonstrated unidimensionality and good interrater reliability in past similar samples (r = 0.86) (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). The Ag Scale is an indicator of outcome in this study and demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .84). A subsample of 141 coded interviews were considered a match (75.9%, n = 107) across two independent raters and provide support for the interrater reliability of the scale.

Panic Disorder Severity Scale – Independent Evaluator (PDSS-IE) Version

The PDSS-IE (Shear et al., 1997) is a 7-item measure for assessing the major features of PD/A that was demonstrated to be the most sensitive measure of outcome for PD/A in a previous clinical trial (Barlow et al., 2000). Each item is rated on a 0 (none/mild) to 4 (extreme/severe) scale, and total scores range from 0 – 14. The PDSS-IE score was one of the main outcomes of the study. A random sample of 10% of the interviews was selected for co-rating by an independent rater. Independent raters listened to an audiotape of the interview and reliability between raters was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients. Interrater reliability (N = 434, ICC = 0.99) and internal consistency (α = .81) were both excellent in this study overall; interrater reliability was not calculated for this maintenance study.

Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) Scale

The CGI (Guy, 1976) is a commonly used global rating instrument in clinical trials consisting of seven-point scales for rating overall illness severity, improvement, and treatment response. IEs used an anchored, interviewer-rated global improvement ranging from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse), and evaluators rated the patient relative to their post-acute treatment status. The CGI has good retest reliability among individuals with anxiety disorders and good inter-rater reliability (Bandelow, Baldwin, Dolberg, Anderson, & Stein, 2006; Zaider, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier, & Leibowitz., 1994). Results of a one-way random intraclass correlation (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) show a favorable degree of reliability on the CGI from the end of Acute CBT to the end of Maintenance CBT, the ICC was 0.78 with a 95% confidence interval from 0.58 – 0.79.

Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) and Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (SIGH-D)

The SIGH-A (Shear et al., 2001) and the SIGH-D (Williams, 1988) are structured formats for administering the Hamilton Rating Scales (Hamilton, 1959, 1960). Both measures have demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability. In the current study recruitment sample, the SIGH-D demonstrated excellent interrater reliability and internal consistency (N = 181, ICC = 0.99, α = .84), as did the SIGH-A (N = 193, ICC = 0.99, α = .86).

Concurrent Treatment Assessment

The current study disallowed concurrent psychotherapeutic or drug treatment aimed at anxiety or panic disorders. At the informed consent for randomization, all patients agreed to refrain from concurrent psychotherapeutic treatment directed at anxiety or panic disorders including any concurrent psychopharmacological treatment that may have anti-panic effects (e.g., SSRIs, benzodiazepines). IEs assessed any concurrent psychotherapy or drug therapy at the major assessments and assessed for concurrent drug therapy at all study assessments.

Patient Self-Report Measures

Demographic and medical history

Sex, age, race, educational history, income, marital status, insurance, and employment status were some of the demographic factors assessed using a self-report questionnaire. A general medical and psychiatric history questionnaire assessed personal and family medical history and current medication use. Some treatment history was confirmed during the ADIS-Lite interview assessment (e.g., history of evaluation or treatment for emotional problems).

Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI)

The ASI (Peterson & Reiss, 1987) is a 16-item self-report scale that is used to assess anxiety focused on panic-related bodily sensations. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .88) in our sample and has been used extensively in research with patients with PD.

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)

The WSAS is used to assess the degree of interference caused by illness symptoms in five life domains (work, leisure, social activities, home, and family) on a 0 (no interference) to 8 (very severe interference) scale. Patients rate five life domains to produce an overall impairment. The WSAS is a modification of scale introduced by (Hafner & Marks, 1976). Total scores range from 0-40, and the scale has adequate test-retest reliability (r = 0.73) (Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002), and good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .80) in our sample.

Adherence Rater Certification and Measures

Training and Certification

Adherence Raters were advanced doctoral psychology students and Ph.D. level clinicians who received extra training and certification under the direction of the Project Director at the Boston site. Training included study of CBT manuals and treatment of at least one case under supervision. Certification involved rating two videotaped training cases that were previously rated by the trainer. To be certified, candidates were required to match with the trainer’s ratings on 70% of items on one case and 80% of items on the other case. The Adherence Raters assessed both therapist adherence and competence using a single scale developed for this study. Adherence raters listened to audiotaped M-CBT sessions and rated the Adherence and Competence Scale. The Adherence raters also reported total session duration and rated patient variables and other general therapist variables. Two sessions from each case were rated by study Adherence Raters.

Adherence and Competence Scale

The Adherence and Competence Scale was developed for this study by the first author. The scale is used to assess two primary therapist factors: protocol adherence and competence in treatment delivery. The scale also assesses other therapist factors (e.g., session management, encouragement of patient involvement in treatment use of Socratic questioning), patient factors (e.g., patent’s comprehension of the material covered, patient participation in the therapy session, completion of home practices, if assigned), and other general therapist factors (e.g., session management, kept session/patient on task, etc.). Each therapist was rated on whether they completed each of the treatment session objectives (0) = No, (1) = Yes, or (N/A) not applicable, as appropriate. Each therapist was also rated on the competence or quality of how they implemented each study aim on a scale from (0) = did not do, (1) = poorly to (4) = excellently. Some of the ratings were session specific (i.e., required elements of the protocol) and some items were general or as needed elements (e.g., address residual agoraphobic avoidance, if any remaining). A total Adherence Score was calculated by taking the percentage of total completed items within all session aims, as applicable (e.g., Adherence score = 87% of all protocol aims were implemented). A total Competence Score was calculated from the average quality rating of all study objectives (e.g., Competence score = 4.0 indicates that the treatment that was delivered was of “excellent” quality).

Procedure

The Institutional Review Boards at all four sites approved this study and all patients signed a written informed consent form. Following acute CBT (described above), patients were classified as either treatment responders or non-responders based on the results of the post-treatment diagnostic assessment. As noted above, responders and non-responders were randomized to separate arms of the trial. Responders, the sample used in this study, were randomized to receive either (a) Assessment only (no additional treatment) or (b) Maintenance– CBT (one session per month for 9 months). At randomization, all patients agreed to adhere to initial study enrollment criteria including the absence of concurrent psychotherapeutic treatment directed at anxiety or panic disorders and no concurrent psychopharmacological treatment that may have anti-panic effects (e.g., SSRIs, benzodiazepines). Responders were followed for a total of 21 months following acute phase CBT, and IEs who were blinded to patients’ randomization condition and progress in the study conducted all assessments. The M–CBT protocol and its content were available only to the M–CBT study therapists, it was not in circulation, and it was not shared in any way with IEs.

Response and Relapse criteria

IEs evaluated patients for response status at the end of the acute phase of the trial that included a structured diagnostic interview and self-report battery. Response status was defined as a 40% reduction of PDSS-IE score relative to baseline (pretreatment) and a CGI score of “much” (2) or “very much” (1) improved relative to baseline study entry. During the maintenance phase, all patients were evaluated by IEs in monthly telephone contacts in which they administered the PDSS and CGI. The monthly IE assessments asked patients about their symptoms during the past month. If a patient showed signs of clinically significant deterioration (as indicated by ≥ 40% increase in PDSS-IE and a CGI of 6 or 7, as compared to their post-acute treatment symptom status) during one of the monthly assessments, the patient would enter “setback” which triggered a change to weekly IE assessments. The study coordinator would contact the patient to explain that the weekly assessments would begin to monitor symptoms and to encourage the patient to practice the exercises their therapist taught them. Weekly assessments were conducted until the patient met relapse criteria and was referred for treatment, or until the patient had two consecutive weeks in which they no longer met setback criteria. Relapse status was defined as two consecutive weeks with both ≥ 40% increase in PDSS score relative to post-acute treatment score and a score of “much worse” (6) or “very much worse” (7) on the CGI scale relative to post-acute treatment status.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using an intent-to-treat analysis based on randomization assignment. We used Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards regression models to examine the relationship of time, randomization condition, and anxiety symptoms at the time of randomization to subsequent recurrence. Survival data were censored by dropout, and every effort was made to contact patients to determine whether dropout was associated with relapse. If dropout was unrelated to relapse, we made every effort to continue data collection until study end or relapse. We assessed for the interaction of these hypothesized predictors with treatment condition, which if present would indicate treatment moderation. We only tested for predictors (main effects and interactions) that were justified empirically and theoretically as outlined a priori. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics, Version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics for the study participants at randomization study entry are reported in Table 1. There were no demographic or clinical differences between patients randomized to M–CBT and those randomized to assessment only follow-up at study randomization at p < .05. These null results help to validate the randomization schedule used in the trial. Results are reported pooled and separately for visual inspection of group means and standard deviations. Of the randomization sample (N = 157), the majority were female (67%). Average age was 38 years (SD = 12 years). The majority of the sample identified themselves as Caucasian (84.7%). Marital status was married (52.5%), never married (34%), and separated or divorced (13%). Data on marital status were not available for a small percentage (0.5%) of the study population. Only 6.4% of patients reported less than 12 years of education. With regard to clinical characteristics, 43% of the sample had a secondary comorbid anxiety disorder and 28% had a comorbid mood disorder either concurrently or a history of significant comorbid mood disorder prior to study randomization. Based on the ADIS-Lite interview, patients reported an average duration of panic disorder of 440.4 weeks (SD = 493.3; Median = 248.1), and approximately one-half of patients (49%) showed some residual symptoms of agoraphobia at study randomization based on the ADIS Ag Scale.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Randomization Study EntryFollowing Acute Treatment Response for PD (N = 157)

| Variable or Characteristic | Overall (N = 157) M (SD) |

Maintenance– CBT (n = 79) M (SD) |

Assessment Only (n = 78) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variable | |||

| Age at acute study entry, y | 37.8 (11.9) | 38.1 (11.3) | 37.5 (12.6) |

| Men, % | 33.2 | 27.8 | 38.5 |

| Married, % | 55.4 | 58.2 | 52.6 |

| White, % | 84.7 | 84.8 | 84.6 |

| Education, < 12 y, % | 6.4 | 3.8 | 8.9 |

| Clinical characteristic | |||

| Panic Disorder Severity Scale score | 4.6 (2.7) | 4.4 (2.7) | 4.7 (2.8) |

| Clinical Global Improvement score | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| Duration of current PD, wks | 440.4 (493.3) | 475.5 (474.2) | 404.5 (514.4) |

| Current PD duration median, wks | 248.1 | 289.3 | 230.4 |

| Lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder, % | 43.0 | 37.0 | 48.0 |

| Lifetime comorbid mood disorder, % | 28.0 | 29.0 | 27.0 |

| Residual symptoms of agoraphobia, % | 49.0 | 50.0 | 48.7 |

| Lifetime history of cardiac problems, % | 12.1 | 11.8 | 13.0 |

| History of psychiatric hospitalization, % | 5.1 | 5.3 | 3.8 |

| ADIS-Agoraphobia Severity score | 3.2 (5.3) | 2.9 (5.0) | 3.2 (5.3) |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index Total score | 12.2 (10.3) | 12.7 (9.8) | 11.8 (10.8) |

| Hamilton Rating Scale Anxiety score | 9.2 (6.2) | 9.4 (6.7) | 9.0 (5.9) |

| Hamilton Rating Scale Depression score | 6.3 (5.2) | 6.0 (5.1) | 6.6 (5.4) |

| Work Social Adjustment Scale score | 3.2 (4.2) | 3.3 (4.7) | 3.3 (4.2) |

Note. Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. CBT = Cognitive Behavior Therapy, PD = Panic Disorder. There were no demographic or clinical differences between patients randomized to Maintenance–CBT and those randomized to assessment only follow-up at study randomization at p < .05.

Group and Site Equivalence

Prior to examining multivariate analyses, analyses were conducted to examine group and site equivalence. Analyses indicated that time to relapse did not significantly differ across the four sites, and the two randomization arms across the sites were not different (i.e., with no differential odds of relapse) at p < .05 during the 21 month follow-up. Post hoc analyses indicated that the patients treated at the four treatment sites showed equivalent time to relapse during the 21 months after acute treatment.

Classification of Treatment Completion Status

The M–CBT treatment protocol required that patients complete a minimum of 6 of the 9 sessions to be considered a treatment completer. This minimum therapeutic dose was to ensure that patients in the M–CBT condition received the critical elements of the treatment protocol within the study period. For the randomized sample, the mean number of M–CBT sessions completed was 7.5 sessions (SD = 0.3, Mode = 9) among the 79 patients randomized to the maintenance treatment.

Attrition Analyses

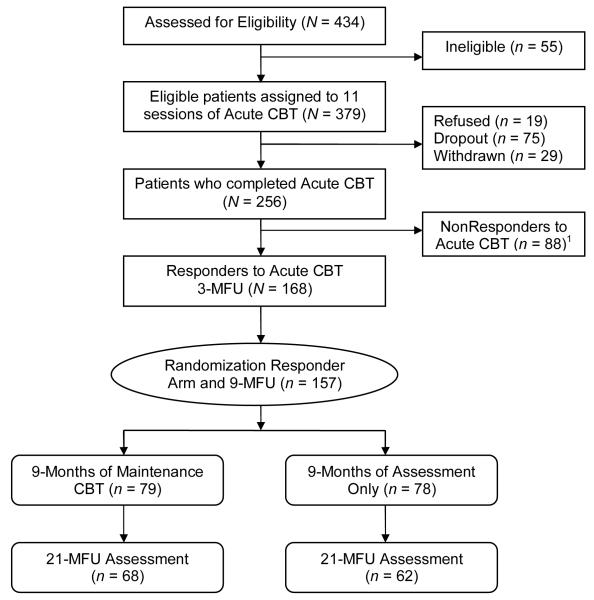

Although attrition during the acute phase of the trial was slightly higher than projected, this attrition was not systematic and did not appear to threaten the validity of the current study (White et al., 2010). In this maintenance study, attrition was small (See Figure 1) and analyses showed no differences in attrition between patients subsequently assigned to M–CBT or the assessment only condition (all χ2s < 1). The reasons some patients ended participation early was due to: study protocol violations (e.g., use of a prohibited medication, prohibited treatment; too many missed M-CBT visits) (n = 8; 30%); they had other significant worsening (n = 6; 22%) or significant PD worsening (n = 1; 3.7%); they improved and did not want to continue (n = 3; 11%), they were discouraged and did not want to continue (n = 1; 3.7%); or they were lost-to-follow-up (n = 8; 30%).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients eligible, enrolled, randomized, and treated in controlled clinical trial for long-term strategies for panic disorder with and without agoraphobia.

1Patients referred to the NonResponder Arm of the Long-Term Strategies for Panic Disorder Trial (Payne et al., 2012).

Treatment Adherence and Competence

Overall, the average independent ratings of therapist Adherence were in the good-to-excellent range by the Adherence Raters (> 80%), with the average Competence rating in the good-to-excellent range (M = 3.1, SD = 0.6). Therapist-patient rapport was rated high (M = 3.2, SD = 0.6) by Adherence Raters. Co-rated tapes indicated excellent agreement among raters based on a two-way random ICC (0.94). Of the total number of M-CBT sessions rated, 15% the individual CBT sessions were rated as “inadequate” on the Adherence Score (i.e., yielding a non-adherent M-CBT session).

IEs assessed patients’ non-study medication use at each time point including use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants. Consistent with the Acute CBT phase of the trial, data suggested good adherence across the two groups, with few patients (n = 5) failing to persistently adhere to the prohibited medication schedule for the study duration.

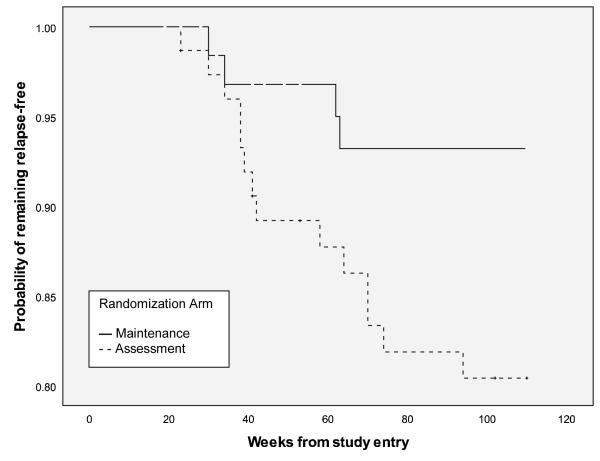

Maintenance Treatment and Its Impact on Outcome at 21 Month Follow-Up

We used product-limit survival analyses to examine the effect of randomization (i.e., M– CBT or assessment only follow-up) on time to relapse. At 21-MFU, the estimated proportion surviving in the maintenance group was 94.8% ± 3%, but in the assessment only group the estimated proportion surviving was 81.6% ± 5%. Analyses indicated that after attrition, patients randomized to the M–CBT (n = 72) had a longer time to relapse after acute-phase treatment response compared to patients randomized to the assessment only follow-up condition (n = 62), generalized Wilcoxon rank χ2(df = 1) = 5.09, p < .05. Figure 2 depicts the probability of remaining relapse-free from PD/A (i.e., maintaining treatment response) from acute study entry. Inspection of the survival curves indicated that among the patients receiving M–CBT, the greatest risks for relapse occurred between 28–31 weeks (i.e., the approximate end of M–CBT), and at 60 weeks. For patients in the assessment only condition, the risk for relapse was comparatively even across Phase 2 of the study; however, the single greatest risk for relapse occurred between 30–40 weeks. Put another way, overall rates of relapse were significantly lower for M–CBT (5.2%) as compared to the assessment only condition (18.4%).

Figure 2.

Plot of probability of remaining relapse-free from panic disorder with/without agoraphobia (PD/A) in acute-phase treatment responders who were randomized to receive either Maintenance CBT (94.8%, n = 72) or assessment only follow-up (81.6%, n = 62) during phase 2 of the clinical trial. Generalized Wilcoxon rank χ2(df = 1) = 5.09, p < .05. Due to variability in duration of study components (i.e., treatment implementation and assessment completion), phase 2 of the study began at approximately week 20, and follow-up extended over approximately 90 weeks following randomization.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Models

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to the data on the total sample. Models examined the impact of hypothesized predictors at randomization (i.e., the end of acute CBT) on time to relapse during the follow-up period, including age, sex, pre-randomization panic disorder severity (PDSS-IE score), agoraphobia severity (Ag Scale score), clinical global improvement (CGI score), as well as randomization group assignment. In the prediction of relapse-free survival, age, sex, PDSS-IE score, and CGI score at the end of acute CBT were not independently predictive of the odds of relapse at p < .05. However, ADIS Ag Score at randomization was independently predictive of time to relapse during follow-up (HR = 1.15, p < .01), with higher agoraphobia scores (indicating more residual avoidance at the end of acute CBT treatment, albeit in the context of meeting responder criteria) having a shorter time to relapse compared to those with lower agoraphobia scores. In other words, there was a 15% increase in the rate of relapse occurring for every unit of increase in agoraphobia score in the model.

The two-way interaction for Age X pre-randomization PDSS-IE was significant at p < .01, indicating that increased age had a significant association among patients with higher panic disorder severity on time to relapse; younger age did not confer similar relations with PDSS-IE scores and time to relapse. All other hypothesized two-way and three-way interactions were entered on subsequent blocks and were non-significant at p < .05. In all survival analyses, standard errors were small suggesting no problems with multicollinearity, and plots indicated that the proportional hazard assumption was satisfied.

At the symptom level, a set of linear regression analyses revealed that the combined sample showed reductions in PDSS scores over time. Bivariate linear regression analyses revealed that panic disorder symptoms at the end of acute CBT was a significant predictor of both 9–month outcome (β = .41, p < .01) and 21–month outcome (β = .45, p < .01), accounting for 16.8% and 20% of the variance in long-term outcome, accordingly. By convention (Cohen, 1988), both analyses showed linear findings with medium effect sizes. Mahalanobis distance tests were examined for residuals, but no outliers were identified or excluded.

We also conducted a descriptive analysis of setbacks and relapses during the randomization study by group. In the assessment only arm of the study, a total of 26 patients entered the “setback” mode. Of these, 14 recovered and continued study participation, and 12 participants were removed from the study because they met criteria for relapse. There were a total of 15 participants who relapsed during the study, including the 12 participants who had entered setback mode, 1 participant who was determined to have an earlier relapse than initially calculated (so did not previously enter setback mode), and 2 participants who were determined to have relapsed without complete data. In the M-CBT group, 11 participants entered “setback” mode at some point during the study. Of these, 5 participants recovered and continued participation, and 5 individuals were removed from the study because they met criteria for relapse. The final participant of these 11 was removed from the study due to a significant worsening of non-panic disorder symptoms. The M-CBT arm resulted in 6 relapses – 5 of whom had already entered “setback” mode and one individual who was classified as relapsed at the final assessment.

Work and Social Functioning at Follow-up

We conducted analyses to examine changes in work and social impairment between the two groups from randomization to the long-term follow-up. First, the pooled mean for the total sample on the WSAS at 21-month follow-up was low (Mp = 2.59, SDp = 4.46, Mode = 0) which indicated that this sample of acute treatment responders was experiencing mild levels of interference at the long-term follow-up. Second, results of a one-way ANCOVA indicated that treatment group assignment was significantly related to changes in WSAS scores at follow-up, after covarying for WSAS scores at randomization, F(1, 118) = 3.80, p = .04, f2 = .05. Planned contrasts revealed that there was significantly greater change on the WSAS total score (i.e., indicating less work and social interference) at follow-up in the M-CBT group compared to the assessment only condition, t(118) = 1.95, p = .04, η 2p = .03. The covariate was not associated with changes over time at p < .05.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that M–CBT, compared to an assessment only control condition, sustains acute treatment gains, prevents relapse, and reduces work and social impairment among patients who responded to an initial course of CBT for PD/A over a 21– month follow up. These results are noteworthy because, although the effects of CBT are thought to be lasting, few data from controlled studies provide support for the long-term efficacy of acute CBT, particularly data collected longitudinally (monthly) over time, in this case 21 consecutive months. These findings have implications for the long-term management of PD/A.

The M–CBT in this study was a manualized protocol aimed at reinforcing acute CBT skills and preventing PD/A recurrence, and further research is needed to dismantle the protocol components as well as examine the contribution of non-specific factors to the maintenance treatment effect. The decision to include an assessment only (i.e., untreated) condition as the main comparison group was necessary to assess how many patients maintained a sustained acute treatment response without any post-acute intervention. This approach is the most usual strategy employed by clinicians for patients who respond very well to treatment, since there is the assumption by many therapists that patients who respond this well have really learned something new, have mastered CBT skills, and require no further treatment (an assumption shared by many of our therapists prior to the study). Indeed, most patients in assessment only did retain their responder status. However, a significant minority (18%) relapsed and this was markedly reduced by monthly maintenance CBT. Nevertheless, this maintenance trial did show that few patients reported seeking non-study therapies. In addition, a longer follow-up will be important to examine the longitudinal durability of M–CBT for PD/A. Our results require replication and extension over follow-up intervals that span several years, because it is possible that remission and relapse may not become problematic until later. As noted, Fava and colleagues (1995) using situational exposure based treatment for agoraphobia found a linear decrease in likelihood of staying in remission (i.e., 96% at 2 years, 77% at 5 years, and 67% at 5 years).

This trial employed rigorous assessment methods but was not without some limits. First, the reliability estimates for some of our clinical interview factors (e.g., PTSD, dysthymia, agoraphobia) were low. All patients in this study were required to have panic attacks at recruitment and therefore the base rate for some of these disorders may be lower than expected. Fortunately, this study did not solely depend upon either of these factors, and patients were required to meet diagnostic criteria for PD and agoraphobia as assessed using the ADIS Ag Score, a highly reliable measure. Also, it is theoretically possible for a patient to have two consecutive weeks in between the monthly assessments during long-term follow-up where s/he would have met criteria for relapse if assessed, but was able to recover prior to the next monthly assessment. In this study, efforts to mitigate this possibility included encouraging patients to contact the study coordinator if symptoms increased, and the study coordinator could initiate IE assessments.

Until longer-term follow-up data are available, results of this multisite randomized controlled clinical trial suggest that the best treatment approach to the long-term care of patients with PD/A includes acute CBT followed by a limited number of monthly maintenance treatment. Our results show that with monthly maintenance therapy, patients show reduced chance of relapse and improved work and social functioning. Moreover, it is likely that monthly maintenance therapy would be cost-effective in light of the burden of disability and substantial societal cost associated with PD (Batelaan, et al., 2007), while recognizing that identifying more precisely who is at relatively greater risk for relapse, and targeting those individuals with maintenance therapy would ultimately be the most cost effective strategy. Our findings reveal functional but moderate group differences, and it is possible that even more cost-effective maintenance CBT approaches and modalities (i.e., self-directed, online, smart phone applications) will be tested in future work. In this study, the most robust predictor was the presence of relatively greater residual symptoms of agoraphobia immediately following treatment, albeit in a perhaps select group of individuals who had responded very well to therapy. It may be conceivable to develop specific identifiers or algorithms to determine who is most likely to benefit from maintenance therapy.

It is unclear if maintenance therapy must last for nine months, even at the somewhat infrequent interval of once a month sessions. Possibly less frequent or even fewer sessions would be equally beneficial but, in the absence of parametric studies, we are unable to make any recommendations along this line. We purposely included more substantial maintenance sessions than might otherwise be given to provide a robust test of their benefit. Nevertheless, the likely public health benefits across large numbers of patients are evident. It is possible that more naturalistic data collection on differing dosages of relapse prevention strategies could be collected across multiple anxiety disorder clinics in the course of their usual and customary clinical care, and that this should shed some light on the question of dosages. For now, a reasonable clinical strategy would indicate continuing maintenance treatment until agoraphobia as well as panic disorder symptoms are no more than minimal in a given patient.

Finally, the observation of relapse, occurring in a somewhat linear fashion over time in the assessment only group, albeit at relatively low levels underscores a need to discover more precisely the basic mechanisms of action in these treatments in order to make therapies more efficient and effective. Findings from basic cognitive and neuroscience suggest that effective treatments for anxiety disorders have as one crucial component the creation of new memories overriding old fear-based associations (Bouton, 2002; Bouton, Mineka, & Barlow, 2001; Bouton & Woods, 2008). Recent findings have emphasized innovative methods for strengthening these new memories such as the utilization of the NMDA partial agonist, D-cycloserine during extinction trials (Otto et al., 2009). Other findings from laboratory research point to basic windows of opportunities lasting several hours after prompting of fear and anxiety in which new memories can be formed and consolidated that would more effectively override fear- and anxiety-based responding (Monfils, Cowansage, Klann, & LeDoux, 2009). Further improvement in these treatments may also mitigate any erosion of therapeutic gains that does occur. Findings along these lines would move us towards the desired goal of more personalized care for mental disorders (Insel, 2009).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH45963, MH45964, MH45965, MH45966). David H. Barlow receives royalties and honoraria for the psychological treatment described in the manuscript.

References

- Aaronson CJ, Shear MK, Goetz RR, Allen LB, Barlow DH, White KS, Gorman JM. Predictors and time course of response among panic disorder patients treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(3):418–424. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Baldwin DS, Dolberg HF, Anderson HF, Stein DJ. What is the threshold for symptomatic response and remission for major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(9):1428–1434. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Craske MG. client workbook. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. (4th ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association. 2000;283(19):2529–2536. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2529. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batelaan N, Smit F, de Graaf R, van Balkom A, Vollebergh W, Beekman A. Economic costs of full-blown and subthreshold panic disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;104(1-3):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.03.013. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(10):976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. doi: doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Mineka S, Barlow DH. A modern learning theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder. Psychological Review. 2001;108(1):4–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.4. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Woods AM. Extinction: Behavioral mechanisms and their implications. In: Byrne JH, Sweat D, Menzel R, Eichenbaum H, Roediger H, editors. Learning and memory: A comprehensive reference. Vol. 1, Learning theory and behavior. Elsevier; Oxford: 2008. pp. 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Long-term outcome in cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: clinical predictors and alternative strategies for assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(5):754–765. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.754. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns LE, Thorpe GL, Cavallaro LA. Agoraphobia 8 years after behavioral treatment: A follow-up study with interview, self-report, and behavioral data. Behavior Therapy. 1985;17(5):580–591. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(86)80096-X. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, Middleton H, Anastasiades P, Gelder M. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;164(6):759–769. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed Lawrence Erlbaum; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DH. therapist guide. 4th ed Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DH. Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 1–64. 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dow MGT, Kenardy JA, Johnston DW, Newman MG, Taylor CB, Thomson A. Prognostic indices with brief and standard CBT for panic disorder: I. Predictors of outcome. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37(10):1493–1502. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000670. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Zielezny M, Savron G, Grandi S. Long-term effects of behavioural treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166:87–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:819–844. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1976. Revised (DHEW Publication No. ADM 76-338) [Google Scholar]

- Haby MM, Donnelly M, Corry J, Vos T. Cognitive behavioural therapy for depression, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder: A meta-regression of factors that may predict outcome. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;40:9–19. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner J, Marks IM. Exposure in vivo of agoraphobics: Contributions of diazepam, group exposure, and anxiety evocation. Psychological Medicine. 1976;6(1):71–88. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700007510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychiatry. 1959;32(1):50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt E, Kipper L, Blaya C, Salum GA, Hirakata VN, Otto MW, Manfro GG. Predictors of relapse in the second year follow-up post cognitive-behavior therapy for panic disorder. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2011;33(1):23–29. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010005000005. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462010005000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katschnig H, Amering M, Stolk JM, Klerman GL, Ballenger JC, Briggs A, et al. Long-term follow-up after a drug trial for panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(4):487–494. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Yonkers KA, Warshaw MG, Pratt LA, Gollan JK, Massion AO, Lavori PW. Remission and relapse in subjects with panic disorder and panic with agoraphobia: A prospective short interval naturalistic follow-up. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182(5):290–296. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavissakalian M, Perel JM. Clinical experiments in maintenance and discontinuation of imipramine therapy in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(4):318–323. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.49.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Smits JAJ, Otto MW. Empirically supported treatments for panic disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;32(3):593–610. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.05.005. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlowicz MV, Stein MB. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):669–682. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monfils M-H, Cowansage KK, Klann E, LeDoux JE. Extinction-reconsolidation boundaries: Key to persistent attenuation of fear memories. Science. 2009;324(5929):951–955. doi: 10.1126/science.1167975. doi: 10.1126/science.1167975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JM. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Price EP. A meta-analytic review of cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across the anxiety disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:521–531. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253843.70149.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost LG, Thulin U, Ramnerö J. Cognitive behavior therapy vs exposure in vivo in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(10):1105–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.004. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Pollack MH, Sabatino SA. Maintenance of remission following cognitive behavior therapy for panic disorder: Possible deleterious effects of concurrent medication treatment. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27(3):473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80028-1. [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Tolin DF, Simon NM, Pearlson GD, Basden S, Meunier SA, Pollack MH. Efficacy of D-cyclocerine for enhancing response to cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.036. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne LA, White KS, Gallagher MW, Woods SW, Shear MK, Gorman JM, Barlow DH. Second-stage treatments for relative non-responders to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: Continued CBT versus paroxetine. 2012. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Peterson RA, Reiss S. Anxiety Sensitivity Index Manual. IDS; Worthington, OH: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Schweizer E. Panic disorder: Long-term pharmacotherapy and discontinuation. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;18(6, Suppl. 2):12S–18S. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199812001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Woolaway Bickel K, Trakowski J, Santiago H, Storey J, Koselka M, Cook J. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder: Questioning the utility of breathing retraining. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):417–424. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.417. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, Papp LA. Multicenter collaborative Panic Disorder Severity Scale. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1571–1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, Endicott J, Lydiard B, Otto MW. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:166–178. al., e. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P, Fleiss J. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel DA, Baker SL. Maintenance CBT Manual for use in the Treatment of Panic Disorder: Long Term Strategies Trial. Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University; Boston, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- van Apeldoorn FJ, Timmerman ME, Mersch PA, van Hout WJ, Visser S, van Dyck R, den Boer JA. A randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or both combined for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: Treatment results through 1-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):574–586. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04681blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KS, Allen LB, Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Attrition in a multi-center clinical trial for panic disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198(9):665–671. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef3627. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45(8):742–747. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Bruce SE, Dyck IR, Keller MB. Chronicity, relapse, and illness–Course of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder: Findings in men and women from 8 years of follow-up. Depression and Anxiety. 2003;17(3):173–179. doi: 10.1002/da.10106. doi: 10.1002/da.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Leibowitz MR. Evaluation of the clinical global impression scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1994;33(4):611–622. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007414. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703007414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]