Abstract

We demonstrate that Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticle (MNP) can greatly enhance the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of metal nanoparticle. The high refractive index and molecular weight of the Fe3O4 MNPs make them a powerful enhancer for plasmonic response to biological binding events, thereby enabling a significant improvement in the sensitivity, reliability, dynamic range, and calibration linearity for LSPR assay of small molecules in trace amount. Rather than using fluorescence spectroscopy or magnetic resonance imaging, this study marks the first use of the label-free LSPR nanosensor for a disease biomarker in physiological solutions, providing a low cost, clinical-oriented detection. This facile and ultrasensitive nanosensor with extremely light, robust, and low-cost instrument is attractive for miniaturization on a lab-on-a-chip system to deliver point-of-care medical diagnostics. To further evaluate the practical application of Fe3O4 MNPs in the enhancement of LSPR assay, cardiac troponin I (cTnI) for myocardial infarction diagnosis was used as a model protein to be detected by a gold nanorod (GNR) bioprobe. MNP-captured cTnI molecules resulted in spectral responses up to 6 fold higher than direct cTnI adsorption on the GNR sensor. The detection limit (LOD) was lowered to ca. 30 pM for plasma samples which is 3 orders lower than comparable study. To the best of our knowledge, this marks the lowest LOD for a real plasma protein detection based on label-free LSPR shift without complicated instrumentation. The observed LSPR sensing enhancement by Fe3O4 MNPs is independent of nonspecific binding.

Keywords: Plasmonic enhancement, Magnetic nanoparticle, Surface plasmon resonance, Gold nanorods, Biosensing, Troponin, Medical diagnostics

Introduction

The optical transduction by gold nanorod (GNR) is based upon the phenomenon of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR or nanoSPR), which arises from light induced collective oscillations of surface electrons in a conduction band.1;2 The extremely intense and highly localized electromagnetic fields caused by LSPR make metal nanoparticles (NPs) highly sensitive to changes in the local refractive index.3–6 These changes are exhibited in a shift of peak wavelength in extinction and scattering spectra in proportional to target binding on the nanorod surface.7 This unique optical property is the basis of their biosensing utility to investigate binding interactions of a variety of biological and pathogenic molecules in a label free approach.8–13 Compared to conventional methods, LSPR assay eliminates detection tags such as fluorescent, enzymatic, and radioactive agents. Unlike fluorophore, plasmonic nanoparticles do not photobleach or blink and as such have been widely used in immunoassays, cellular imaging, and surface-enhanced spectroscopies.14;15

Since the initial LSPR assay based on plasmonic NPs in suspension, this biosensing modality has gained increasing attention. Dependent on the system, numerous studies have reported detection limits of nanomolar level for serum and picomolar for buffers.16–22 However, most of these proof-of-concept demonstrations used either a streptavidin-biotin model system or buffered solutions except for few study in diluted serum. An LSPR assay may be a challenge to detect small molecules because the binding events usually cause a small change in the refractive index of the medium. Detecting real biomarkers in physiological fluid samples can dramatically impair the LSPR assay sensitivity, dynamic range, and specificity because of biofouling and nonspecific binding.23 These uncertainties and drawbacks have limited the practical use of this simple LSPR nanosensor in the clinical environment for medical diagnostics. Motivated by these concerns and by the prospect of improving the LSPR sensitivity and selectivity by exploring magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), we describe in this paper, for the first time to our knowledge, the significant plasmonic response enhancement on gold nanorods by iron oxide (Fe3O4) MNPs. More importantly, label-free nanosensors can detect disease markers to provide point-of-care diagnosis that is low-cost, rapid, specific, and sensitive.24;25 With the use of dark field microspectroscopy system, Nusz et al. showed that biotin conjugated single gold nanorod can detect streptavidin with a sensitivity down to 1 nM.26 However, the requirement of a benchtop scale microscopy greatly reduces the clinical relevance and ultraportable potential of these LSPR nanosensors. In this sense, we believe that a strategy to amplify the spectral response of the LSPR using functionalized MNPs is attractive.

Herein, the application of MNPs in an LSPR nanosensor is two fold. Because LSPR is highly sensitive to the amount of target molecule bound to the nano-surface, the high refractive index (~ 2.42) and high molecular weight of iron oxide nanoparticles27;28 are expected to amplify the LSPR spectral shift upon biological binding. This will enable an ultra-sensitive detection of all kinds of biomolecules. Additionally, the high surface-to-volume ratio of MNPs allows a high density of chemical binding and the magnetic properties allow direct capture, easy separation, and enrichment of target molecules in complex samples such as blood plasma.29 Altogether, these advantages make Fe3O4 MNPs an excellent candidate in enhancement of LSPR signals. On the other hand, this label-free LSPR nanosensor provides an innovative bioassay for DNA, RNA, peptides, and proteins separated and concentrated from physiological solutions under an external magnet by the use of MNPs as carriers. The simple, in situ, and cost-effective MNP mediated (enhanced) LSPR assay without the requirements of detection labels and benchtop instrumentation setups is more favorable for point-of-care bioassay in clinical settings over electrochemical method, IR spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, magnetic atomic force microscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging.30–33

To further demonstrate the practicability of the MNP amplification effect in enhancing LSPR sensitivity, we performed a systematic study to detect cardiac troponin I (cTnI) concentrations in blood plasma as a model system. cTnI is a clinically preferred biomarker for myocardial necrosis. It has nearly absolute myocardial tissue specificity as well as high clinical sensitivity, thereby reflecting even microscopic zones of myocardial necrosis.34 We demonstrate in this study, for the first time to our knowledge, the enhancement of LSPR spectral shift by Fe3O4 MNPs to enable ultrasensitive quantification of cTnI at ca. 30 pM in physiological solutions with simplicity and portability.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate trihydrate (HAuCl4; 99%), sodium borohydride (99%), Cetyltrimethylammoniumbromide (CTAB), L-ascorbic acid, silver nitrate (99%), dodecanthiol (DDT), 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUDA; >95%), human plasma, fibrinogen, and serum albumin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimidehydrochloride (EDC), N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS), ferric chloride, and ferrous chloride were from Fisher Scientific (Rochester, NY). Highly purified human cardiac troponin I antigen (cTnI) and specific murine monoclonal antibody pairs targeting for different cTnI epitopes (aa 24–40 and 87–91 respectively) were from Fitzgerald Industries (Acton, MA).

Surface modification of Au nanorods to construct specific biological probes

Gold nanorods of 80–100 ml were chemically synthesized using seed mediated growth method with modifications.35–37 Absorption spectra of the prepared Au nanorod solutions were obtained on a Beckman-Coulter UV-NIR (200 – 1100 nm) scan spectrophotometer. Electron microscopy images of the nanorods were taken using Hitachi scanning electron microscope (SEM). The SEM grid was dropcast with a total of 10 Jl of the purified rod solution and allowed to air dry in the open atmosphere. For each sample, the size of 200 particles was measured to obtain the average rod dimension, aspect ratio, and yield. The yield was calculated by number of rods divided by total number of particles (× 100%).

To construct specific LSPR bioprobes, biological receptors such as antibody need to be efficiently immobilized on the gold nanorod surfaces. Since CTAB is used as a capping agent during synthesis to prevent aggregation of Au nanorods, this results in rod surfaces covered by CTAB bilayers.35 Replacement of this CTAB coating by carboxyl groups can be achieved through round-trip phase transfer ligand exchange developed by Wijaya and Hamad-Schifferli with slight modifications.38 Briefly, 4 mL dodecanthiol (DDT) and 8 mL acetone were added to 2 mL highly concentrated nanorod solution and gently swirled. The thiol group in DDT has a stronger affinity to gold, thereby exchanging the CTAB adsorption layer off nanorods. A clear separation of the aqueous and organic layers was present with extraction of DDT coated gold nanorods in the top organic layer. After discarding the CTAB containing aqueous layer, the solution was centrifuged (5000 rpm for 15 minutes) into a pellet and resuspended in 2 mL toluene via sonication (20 minutes). This suspension was then added under vigorous stirring to 9 mL 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUDA; 0.01M in toluene) at 70°C. The solution was allowed to cool down to room temperature as the nanoparticles settled to the bottom. Within 15 minutes, visible black aggregates confirmed the successful coating of nanorods with MUDA. After deprotonation with 3 mL isopropyl alcohol, the aggregates were finally redispersed in 1 mL of Tris-borate EDTA buffer. The self-assembly of MUDA on nanorods display carboxylic groups (-COOH) at their surface to which anti-cTnI molecules were covalently attached via NH-CO bonds through EDC-NHS linkage.39;40 ELISA was performed to confirm the high affinity and specificity of the LSPR nanosensor for cTnI molecules.

Synthesis and functionalization of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles

Monodispersed Fe3O4 MNPs were synthesized using the following procedure.41 Typically, a mixture of FeO(OH), oleic acid, and 1-octadecene was heated under stirring to 320 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere to avoid any undesired oxygenation. The solution turned from turbid black to clear brown indicating a formation of an iron carboxylate salt. The pyrolysis of the precursor material resulted in the formation of a clear black solution consisting of Fe3O4 nanocrystals. The resulting MNPs were precipitated with acetone and purified with CHCl3/acetone (1:10) until a powder of MNPs was obtained. To prepare the MNPs for biofunctionalization with antibody, nanocrystal powder was first transferred to PBS buffer using literature methods with modifications.42 Briefly, Fe3O4 MNPs were dispersed in the carboxy group modified amphiphilic polymer solution containing a mixture of poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene) and 2-(2-aminoethoxy)-ethanol in chloroform. The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature (molar ratio of Fe3O4/polymer was approximately 1:10). Then, PBS buffer (10 mM) was added to the chloroform solution of the above solution with equal volume, followed by rotary evaporation at ~ 40 °C to remove chloroform. Ultimately, this procedure resulted in a water-soluble carboxyl-terminated iron oxide MNPs in a clear dark purple solution. Once the surface modification of magnetic nanostructures in aqueous PBS buffer was achieved, anti-cTnI molecules were immobilized onto the carboxyl-coated MNPs through the established EDC/sulfo-NHS chemistry.39;40 The resulting biofunctionalized MNPs were precipitated from excess anti-cTnI solution by magnet (~12,500 Gauss) three times with PBS buffer. ELISA was performed to confirm the conjugation of anti-cTnI molecules with binding activity to target antigen. While the magnetic nanoparticle only (negative control) showed a minimal signal, the antibody conjugated MNP nanoparticles demonstrated comparable signal intensities with the free-form antibody sample (positive control).

Fe3O4 MNPs mediated LSPR bioassay

Once the specific antibody is immobilized on the gold nanorod (GNR) surface, the functional GNR sensor (1 ml) was mixed with equal volume of human blood plasma spiked with respective cTnI concentrations in the sensing range. Unless otherwise noted, all the plasma samples were 40% diluted to minimize the adverse effect of high viscosity on sensing performance.23 The mixture was then incubated under mild agitation (500 rpm shaker) for ~ 1.5 hours until reaction equilibrium between the cTnI molecules in the solution and the anti-cTnI immobilized on the GNR sensor surface. Afterwards, the absorption spectrum was measured using a UV-vis spectroscopy (Beckman-Coulter) to observe a pronounced red shift of longitudinal plasmon peak which is proportional to the amount of cTnI binding.

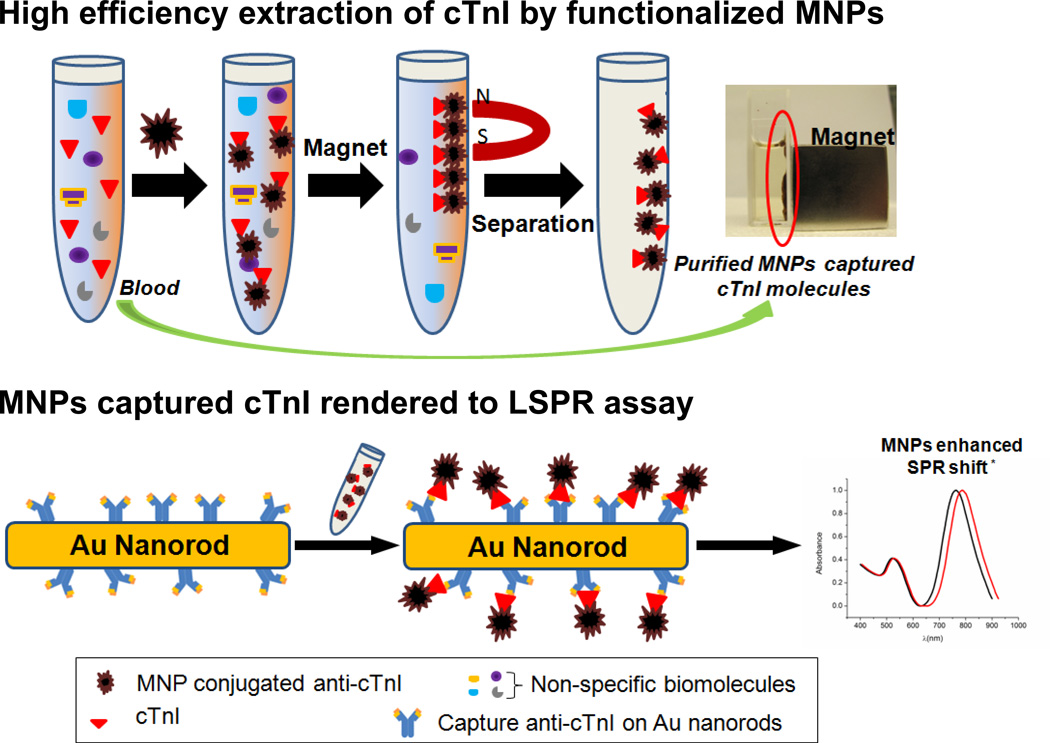

In the cases for LSPR sensing enhanced by Fe3O4 MNPs, the detection procedure typically consisted of two steps. First, blood plasma samples containing various cTnI concentrations respectively were incubated with functional MNP conjugates to selectively extract the target analyte (e.g. cTnI) by magnet and washed twice in PBS buffer. The resulting MNPs-enriched cTnI molecules were then rendered to nanoSPR assay as described above to assess the enhancement in the LSPR spectral shift.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of gold nanorods and biofunctionalization

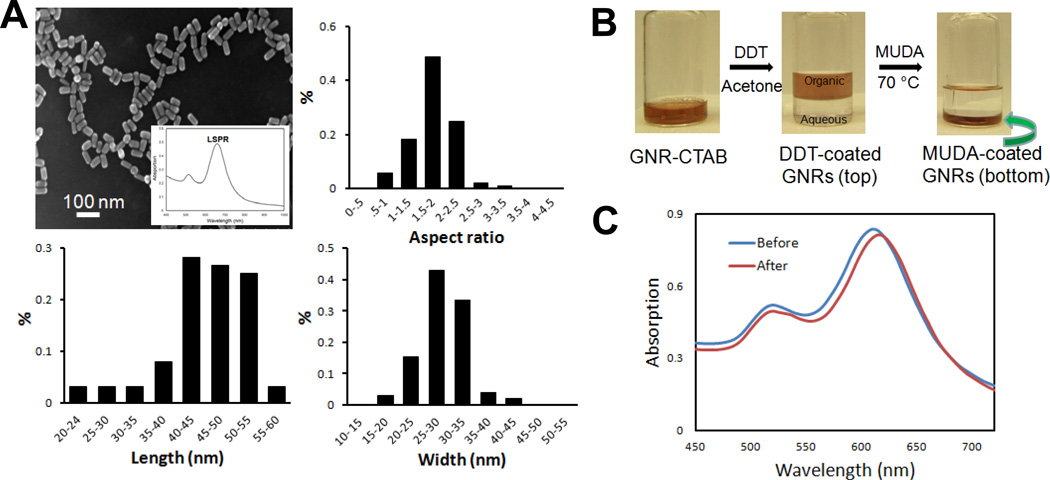

The essential nanomaterial in this study is gold nanorod (GNR). The interaction between the metal conduction electrons and the electric field component of incident electromagnetic radiation leads to strong, characteristic absorption bands in the visible to infrared part of the spectrum.36;37 Figure 1 shows the electron microscopy of synthesized gold nanorods, where rod-shaped nanoparticles are well dispersed and uniformly distributed in size. The absorption spectrum of the GNRs (inset of panel A) typically exhibit two surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peaks. The first plasmon peak at 520 nm corresponds to the transverse oscillation of electrons of Au. The SPR peak at 650 nm is due to the longitudinal oscillation of electrons along the length of the rods. This second peak is prominent at longer wavelengths and changes with respect to the aspect ratio of the rods. By varying reaction parameters such as silver ion concentration and seed/Au3+ ratio, gold nanorods with tunable LSPR wavelength from 650 to 1050 nm (AR: 1.5 – 8.9 respectively) were synthesized (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Synthesis and biofunctionalization of Au nanorods to construct a specific LSPR sensor. A: Scanning electron microscopy, size distribution and aspect ratio of Au nanorods demonstrating a longitudinal plasmonic peak at 650 nm. Inset: characteristic absorption spectrum of Au nanorod showing dominant surface plasmon resonance in the longitudinal direction (LSPR). B: Surface modification of CTAB capped gold nanorod (GNR-CTAB) by phase transfer ligand exchange to functionalize the nanoparticle with carboxyl group. DDT: dodecanthiol; MUDA: 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid. C: Absorption spectra of Au nanorod before and after MUDA coating to functionalize the nanoparticle surface with carboxyl terminals for antibody immobilization.

The seed mediated growth solution method results in a double layer of CTAB molecules attached onto the nanorod surface. This is problematic for surface modification with bioconjugates to functionalize the GNRs. These features have impaired the use of nanorods in biological applications, especially compared to Au nanospheres. Here, we performed a ligand exchange to replace CTAB bilayer by 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUDA) to modify GNR surface with carboxyl terminals. Compared to biological adsorption through electrostatic interaction, this method is robust to covalently immobilize biological receptors to construct GNR molecular probes. As shown in Fig. 1B, mixing CTAB capped GNR (CTAB-GNR) with dodecanethiol (DDT) resulted in a displacement of CTAB because thiol (-SH) groups in DDT has a higher affinity to Au. Addition of acetone caused an aqueous-organic phase separation where gold NRs were extracted into DDT (top portion), leaving CTAB in the bottom aqueous solution. Further processing of the DDT coated GNRs with MUDA at 70 °C in toluene caused an aggregation, indicating MUDA self assembly monolayer (SAM) on the surface of GNRs (MUDA-GNRs) which are insoluble in toluene. UV-vis absorption spectra confirmed the MUDA coating by a 10 nm shift (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with theoretical prediction and literature.38 No significant broadening of the LSPR peak indicates very little nanoparticle aggregation during the process.

Characteristic of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticle

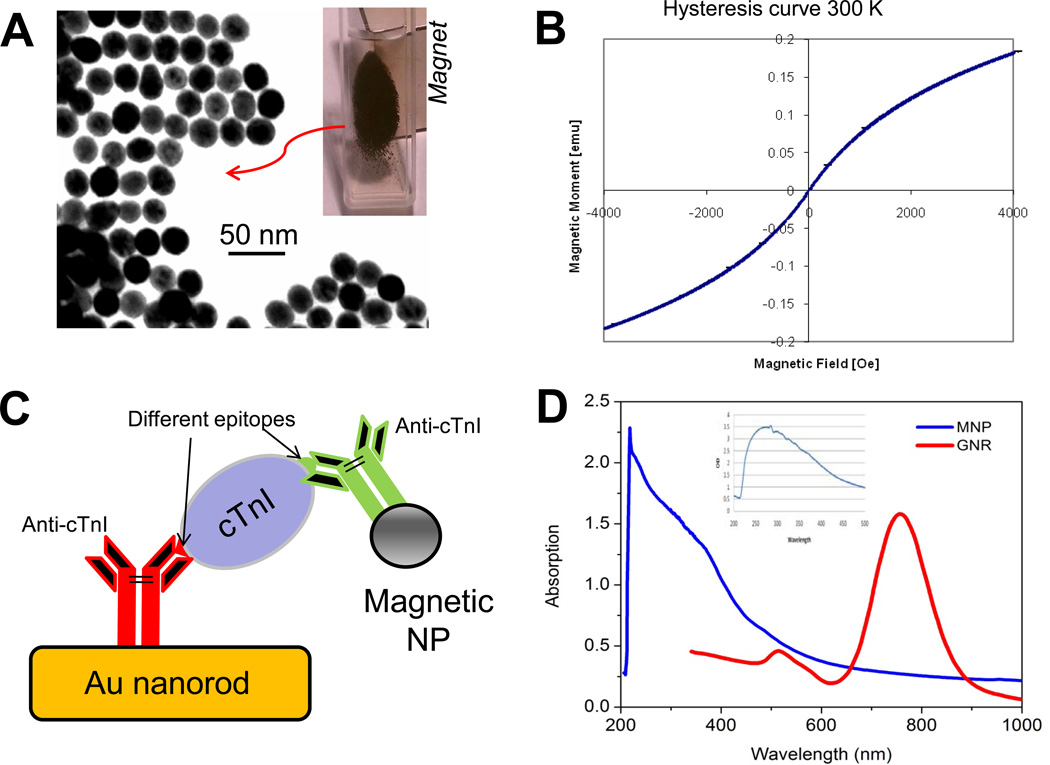

Fig. 2 shows the TEM image of the prepared Fe3O4 MNPs with an average size of 20.5 ± 5.6 nm. The monodispersed magnetite MNPs show a relatively uniform size distribution. These nanoparticles are very stable without precipitation and retain their magnetic properties for months. The MNPs exhibit an excellent superparamagnetism with very little hysteresis. Under an external magnetic field, these Fe3O4 nanoparticles demonstrate a very high response, resulting in a black cluster in the solution as the MNPs are attracted to the magnet side (Fig. 2A inset). After functionalizing with biological receptors, the Fe3O4 MNPs allow a specific bioseparation of target analyte (e.g. cTnI in this study) from complex biological samples. The enriched MNP-cTnI sample can then be quantified by GNR probes where MNPs can significantly enhance the LSPR spectral shift caused by cTnI binding. Fig. 2C depicts a schematic of the MNP-mediated LSPR bioassay. To minimize the competition between functional GNRs and MNPs, a pair of antibodies (anti-cTnIs) with affinity for different epitopes on the cTnI molecule is used. The antibody with binding site for aa 87–91 is used to functionalize the GNRs, while anti-cTnI for aa 24–40 on MNPs.

Figure 2.

Synthesis, characterization and application of Fe3O4 superparamagnetic nanoparticle (NP) in LSPR assay. A: TEM image of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticle. Inset: black aggreates of MNPs in the suspension under magetic field. B: Hysterisis measurement. C: Schematic of MNP mediated nanoSPR assay on gold nanorod. D: Absoption spectra of Fe3O4 MNPs (blue) and antibody-MNP bioconjugates (inset). There are minimal interference with the plasmonic bands of Au nanorod (red).

Fig. 2D shows the spectra of magnetite MNPs (blue) and its conjugate with antibody (inset). It is evident that the absorbance of Fe3O4 decreases monotonically with increasing light wavelength in the 200 – 100 nm range.43 There is a minimal overlap of iron oxide absorption with the two distinct peaks (520 and 780 nm, respectively) characteristic of Au nanorods. Upon immobilization of the cTnI antibody on the MNPs, only a strong absorption band around 280 nm appears. This peak is similar to absorption peak characteristic of free form anti-cTnI, confirming a successful attachment of antibody onto the MNP surfaces. These data suggests a minimal optical interference of the Fe3O4 MNPs which may artificially augment LSPR signals from the GNR nanosensor.

Effect of Fe3O4 MNPs on enhancement of LSPR spectral shift

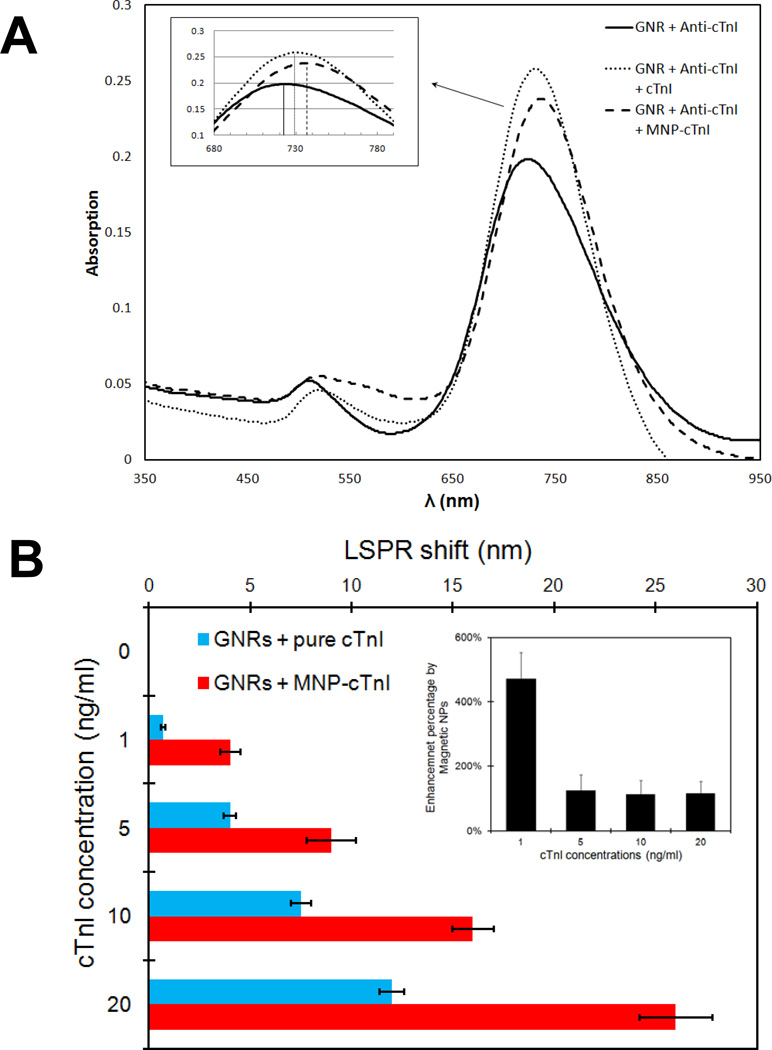

Specific target binding on the GNR molecular probes result in a LSPR spectral shift which is caused by refractive index change in the medium. For most molecules with a relatively high refractive index compared to solvent or air, binding to gold nanorod probes exhibits a red shift of the plasmon resonance wavelength.3 Fig. 3 shows the spectra of the GNR bioprobe in response to the binding of cTnI at 10 ng/ml (330 pM; median of the sensing range) with and without Fe3O4 MNPs respectively. At baseline where GNRs were functionalized with antibody only, the LSPR wavelength was 722 nm. Upon direct adsorption of cTnI molecules, the plasmonic wavelength showed a red shift of 6 nm. As a comparison, the MNP-captured cTnI resulted in shift more than doubled to 13 nm from baseline. This was the case for all the cTnI concentrations in the clinical sensing range (Fig. S1 in supporting information). Fig. 3B summarizes the effect of MNPs mediated LSPR enhancement at various cTnI concentrations. There was an average of 210 ± 50% increase in the red shift by the application of Fe3O4 MNPs (inset). Most importantly, the sensitivity of the LSPR sensor was significantly improved by the MNPs mediated enhancement, thereby enabling an ultrasensitive cTnI assay at 33 pM. Without magnetic nanoparticles, the LSPR shift for cTnI detection at 1 ng/ml (33 pM) is ~ 1 nm. This number is comparable to the background noise of a GNR sensor. However, MNP-cTnI conjugates showed up to a 6 fold increase in the LSPR shift and this signal amplification achieved a detection limit (LOD) for plasma cTnI assay to ca. 30 pM with a S/N ratio > 3. This level is 3 orders of magnitude lower than the detection limit of the GNR biochip for bio-streptavidin binding in 40% diluted serum previously reported.21 To the best of our knowledge, this marks the lowest LOD for label-free serum biomarker detection based on LSPR spectral shift using a simple UV-vis spectrophotometer. Further study of the LSPR enhancement by optimizing the Fe3O4 NPs size, concentrations, magnetic properties, etc. is expected to further push the GNR sensing system limits.

Figure 3.

Enhancement of LSPR response by magnetic nanoparticle. A: Representative absorption spectra of gold nanorod bioprobes before and after specific binding of cTnI antigen at 10 ng/ml (330 pM) with (dashed) and without (dotted) functional magnetic nanoparticles. B: Comparison of the longitudinal SPR red-shift in response to respective cTnI concentrations in the sensing range with (red) and without (blue) magnetic nanoparticle respectively (inset: summary of enhancement percentage by MNPs at various concentrations).

cTnI quantification by MNP enhanced LSPR assay in blood plasma

To demonstrate the practical application of the LSPR sensitivity enhancement by Fe3O4 MNPs, we performed a model study of quantifying plasma cTnI concentrations in its clinically relevant range. The median level of healthy subjects < 60 years of age is 3.2 pg/ml.44 There is a statistically significant increase in mortality with increasing levels of cTnI (P<0.001). The cut-off cTnI value for myocardial infarction is 0.4 ~ 1 ng/ml and can be elevated up to 20 ng/ml in serious situation.44–46 Each increase of 1 ng/ml in the cTnI level is associated with a significant increase (P = 0.03) in the risk ratio for death.47 Accordingly, the target assay range was determined to be 1 - 20 ng/ml (0.05~10 nM). Our sensor is designed in such a way that the quantitative data can aid in risk stratification of the cardiac patients to deliver appropriate, prime time medical care.

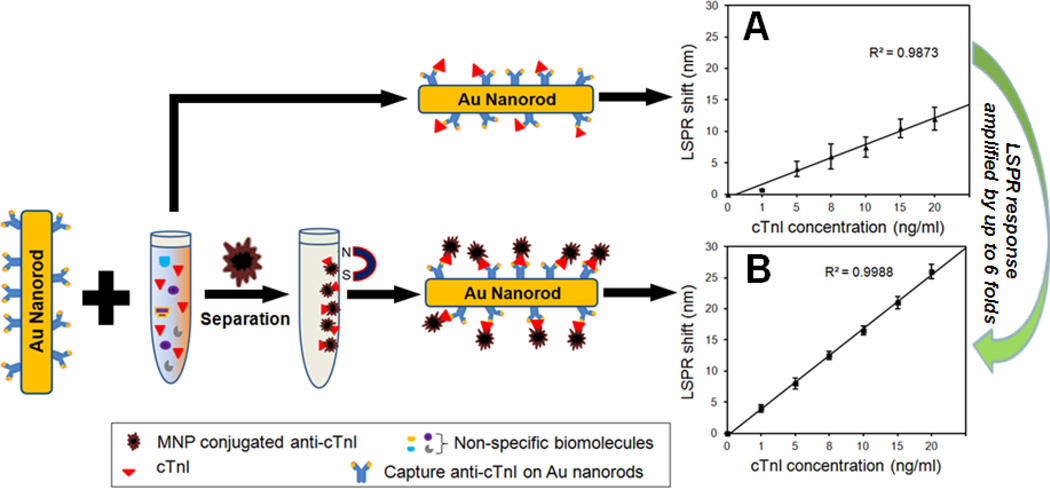

We first performed a control study to assess the LSPR shift upon cTnI binding using spiked blood plasma, because this information is largely unknown. The conventional LSPR measurement without Fe3O4 MNPs only showed 2–5 nm spectral shift due to extremely low cTnI amount. Fig. 5A shows the calibration curve of LSPR red-shift as a function of the cTnI concentrations in the sensing range. The rate of the shift in resonance wavelength of the GNR sensor decreased with increase in the concentration, probably caused by saturation or steric hindrance of the binding sites on the sensor. The detection limit was found to be 5 ng/ml (150 pM), which is not satisfactory for a clinical diagnosis. Due to the complexity of plasma sample, the variation in each data point was also larger than other LSPR sensing in buffer solutions,11;12 as noted by the standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Effect of the magnetic nanoparticle enhanced LSPR on sensitivity, dynamic range, and reliability of cTnI assay in 40% diluted human blood plasma. A: Standard curve of LSPR shift as a function of cTnI concentrations without MNPs. B: Standard curve calibration for MNP enhanced LSPR assay, showing an improved linear relationship between the cTnI concentrations and the LSPR shift resulting from specific binding of Fe3O4 MNP-cTnI conjugates. The LSPR responses are amplified by up to 6 fold.

Next, a cTnI detection in blood plasma was carried out with Fe3O4 MNPs. Fig. 4 shows the schematic of the magnetic nanoparticle enhanced LSPR assay. Mixing of blood samples and functionalized Fe3O4 MNPs in the presence of an external magnet results in a specific extraction of cTnI molecules from the physiological sample, in this case blood plasma. The MNP amount is excessive as compared to the target analyte concentration to ensure maximal and efficient cTnI capturing. The purified cTnI-MNPs conjugates are then rendered to LSPR assay using gold nanorod probes. Fig. 5B shows a linear relationship between the spectral shift and cTnI concentrations (R2 = 0.99). With the MNP enhancement in spectral sensitivity, defined as relative shift in resonance wavelength with respect to the refractive index change of surrounding medium, the standard curve is capable of clearly differentiating cTnI amounts in the sensing range, thereby allowing extrapolation of the cTnI levels in clinical samples for diagnostics. It should be pointed out that although MNPs mediated LSPR assay requires sample extraction by functionalized magnetic nanoparticles, this additional step is justifiable by the significant improvement in sensitivity, reliability, dynamic sensing range, and linearity of the standard curve.

Figure 4.

Schematic showing bioseparation of target molecules from blood plasma by functional Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), followed by MNP mediated nanoSPR assay. The application of MNP results in an enhancement of the LSPR shift at peak absorption wavelength. * schematic for illustration only.

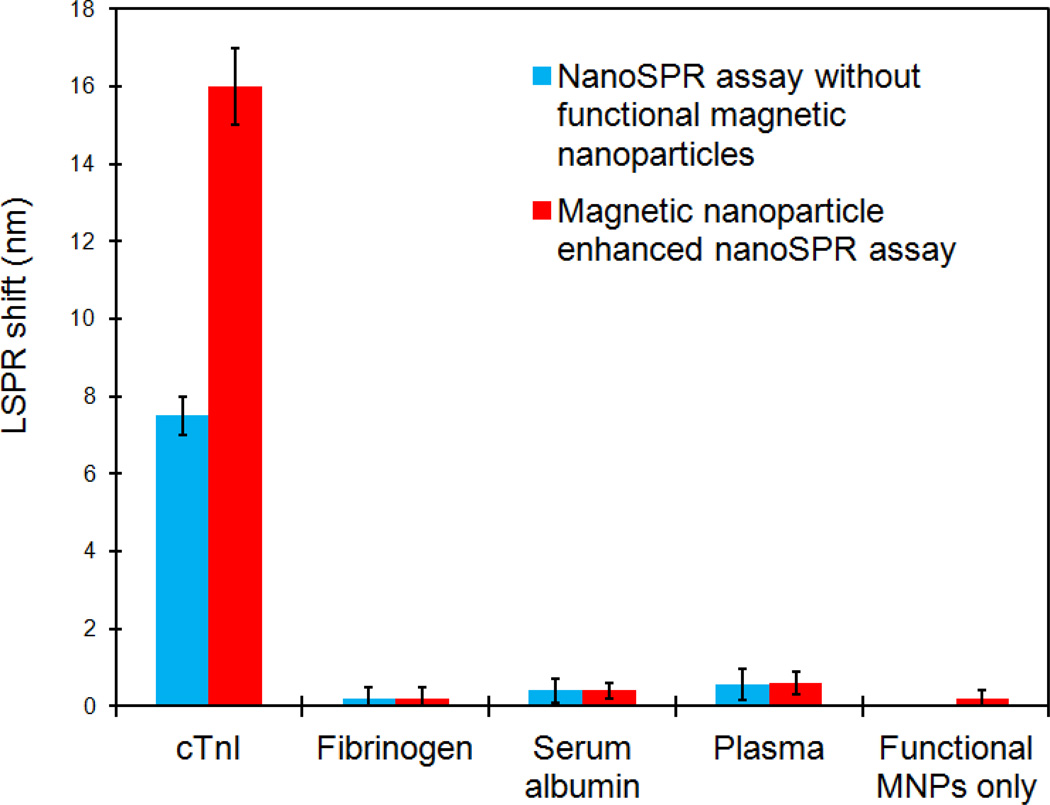

Nonspecific binding

Equally important as sensitivity, specificity of the MNPs enhanced LSPR assay is a prerequisite for an accurate quantification of target molecules in blood samples. As such, we systematically evaluated the nonspecific binding of control biomolecules commonly present in plasma samples, such as fibrinogen and serum albumin. The blue bars in Fig. 6 represent the LSPR responses without magnetic nanoparticles when the cTnI sensors were directly probed by cTnI (positive control), fibrinogen, serum album, and cTnI-free plasma respectively. While the cTnI sample at 10 ng/ml (median of the sensing range) caused a 7.5 nm red shift in the absorption peak, fibrinogen, serum albumin, and control plasma samples at their physiological concentrations showed only a 0.2, 0.4, and 0.5 nm shift respectively. This data suggests a negligible nonspecific binding. To elucidate the effect of the LSPR signal amplification by Fe3O4 MNPs on the nonspecific binding, these sensors were further exposed to MNP-anti-cTnI conjugates. The red columns in Fig. 6 are the LSPR shifts caused by the adsorption of functional MNPs. As expected, the cTnI sensors showed a significant enhancement in the plasmonic response from 7.5 nm shift in control to ~ 16 nm. More importantly, there was little amplification of the background noises. In the presence of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, the LSPR wavelength shift for fibrinogen, serum albumin, and plasma remained at a minimal level of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 nm respectively. Additionally, when the functional magnetic nanoparticles were directly mixed with the GNR sensors without cTnI molecules, no significant SPR shift was observed. Altogether, these data confirmed that the enhancement by Fe3O4 MNPs is unequivocally a direct and specific amplification of the LSPR shift caused by molecular recognition of cTnI by gold nanosensors.

Figure 6.

High specificity of the LSPR assay for cTnI detection in plasma samples. Application of functional Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticle results in signal amplification of the LSPR shift caused by specific cTnI binding only, with minimal effect on the nonspecific binding and background noise.

In discussion, the observed enhancement in the LSPR biosensing can be attributed to at least two features of Fe3O4 MNPs: (1) high refractive index (RI) and (2) high molecular weight. Magnetite has a RI of 2.42 which is much higher than solvent and air. SPR response is known to be highly sensitive to changes in the localized RI or thickness of the medium in the vicinity of the nanorods, especially for molecules with high mass change.3;21 Au nanoparticle labeled antibody was previously demonstrated to increase the LSPR shift by up to 400% as compared to comparable concentrations of native antibody bound to Ag nanoprism sensor.48 Moreover, the high mass density of the MNPs may contribute to the LSPR signal amplification as nanoparticles have been shown to greatly enhance the sensitivity of SPR spectroscopy owing to the large molecular weight of NPs in spite of small size.49–54 Our study corroborated these findings. A combination of these two mechanisms resulted in a 6 fold increase in LSPR sensitivity for MNP enriched cTnI detection in plasma.

As noted in macroscale SPR, direct adsorption of Fe3O4 MNPs causes a much higher SPR angle shift than that resulting from the adsorption of most biomolecules under the same concentrations.55 This could lead to a false SPR amplification from nonspecific MNP binding. Our study demonstrated a minimal amplification of the LSPR noises from irrelevant biomolecules and Fe3O4 MNP itself, which is consistent with other report.27 This can be attributed to the high specificity of the antibody against cTnI and minimal cross-reactivity between the antibodies on the gold nanorods and magnetic NPs. More importantly, the sensitivity of LSPR sensor to the surrounding medium is strongly distance-dependent.21 Gold nanorods can detect a refractive index change up to a distance of 20–40 nm from the surface. Considering that average size of the fabricated MNPs are 20–30 nm, only the magnetic NP conjugated to the cTnI which is bound onto the nanorod sensor surface will cause LSPR enhancement. Those unbound MNPs outside of the sensing distance should not perturb the local refractive index and thereby minimizing the nonspecific optical transduction.

In addition to amplifying the LSPR signal, the strong magnetic properties of Fe3O4 MNPs can be exploited to separate the target analyte from physiological solutions using an external magnet and overcome the intrinsic bioanalytical difficulty associated with physiological solutions due to biofouling and nonspecific binding. The separation/amplification protocol facilitates practical use of the facile LSPR sensor for plasma biomolecule detection by minimizing the adverse effect of limited mass transport in high viscosity.23;56 These factors mark the unparalleled advantages of Fe3O4 MNPs for LSPR sensitivity enhancement in plasma samples over tailoring the LSPR property of core-shell gold nanorods.57 It is noteworthy that capturing efficiency of the MNP system may directly influence the detection reliability. During our study, standard calibration curve was generated in the sensing range with more than 10 replications for each measurement. The capturing efficiency was relatively constant for a specific analyte amount, as implied by the small standard deviation. Even though the capturing efficiency is varying at different concentrations, it has been self-referenced by the fitted calibration of spectral shift vs. spiked cTnI concentration instead of the actual amount of captured molecules, thereby minimizing the effect of MNP capturing efficiency on sensor reliability. It is no doubt, however, enhancement of the analyte capturing by MNPs especially at lower concentrations can significantly improve the sensitivity as more target molecules will be bound on the LSPR sensor. Our efforts are focused on this aspect of the sensor optimization.

Finally, we wish to comment on the instrumental simplicity of the MNP enhanced nanorod sensor to greatly facilitate field-portable environmental or point-of-care medical diagnostic applications. Although single gold nanorod can be more sensitive in LSPR assay than ensemble average measurements as demonstrated by Chilkoti group,26 the detection requires benchtop scale and expensive instrumentation such as dark field microspectroscopy. Theoretical and experimental studies by El-Sayed group showed sharper and more intense resonance peaks in the Ag nanorods, which give them better advantage in their use as sensors.3 However, plasmonic silver material is more prone to oxidation, less biocompatible, and more difficult to handle and functionalize than gold. In addition, Van Duyne group showed that LSPR sensor using Ag triangular NPs fabricated by nanosphere lithography (NSL) can detect streptavidin with a reported limit of <1 pM.58 Nevertheless, this is at a cost of loss in portability and economy due to the NSL fabrication and impractical operation under nitrogen. In this sense, with the Fe3O4 MNPs enhancement to achieve a comparable or better sensitivity for plasma markers, all the advantages of gold nanorods based LSPR assay are retained. The nanorods can be chemically fabricated with precise control of the size, aspect ratio, and concentration. This allows an easy tuning of the longitudinal plasmon peak wavelength to fall in the "optical transparent" (700–900 nm) window ideal for physiological samples such as whole blood. The nanosensor can be implemented using extremely simple, small, light, robust, low-cost optical detector for unpolarized, UV-visible extinction spectroscopy. Unlike the benchtop SPR sensors using a planar gold film, the all-nanoparticle based label-free biosensing modality provides an attractive pathway to miniaturization with a lab-on-a-chip system, positioning this technology for a rapid translation to clinical settings.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the enhancement effect of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles on localized surface plasmon resonance to result in increase in the spectral shift up to 6 folds upon specific binding. The detection limit of the gold nanorod based LSPR assay was significantly lowered to picomolar level for plasma cTnI detection with high specificity. The high refractive index, high molecular weight, and strong superparamagnetic properties of the Fe3O4 MNPs make them a powerful amplifier to meet the ever-increasing demand for sensitivity in small molecule detection of physiological samples. This is achieved using a simple UV-visible spectrophotometer to monitor the label-free, resonance spectral shift of Au nanoprobes without expensive and complicated instrumentation. Optimization of the MNP size, concentration and functionalization to enhance the capturing efficiency of target molecules from complex samples and precise manipulation to bring MNPs closer to the LSPR nanostructures will further improve the LSPR enhancement and assay sensitivity. This ultrasensitive nanosensor is highly suitable to be integrated with a miniaturized optical detector to perform onsite analysis of trace target molecules for medical diagnostics, environmental protection, food safety and homeland security.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was partly supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (SC1HL115833) and San Antonio Area Foundation. Authors thank Dr. Wilhelmus Geerts at Texas State University, San Marcos, TX for hysteresis measurement of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles.

Footnotes

Supporting information

Absorption spectra of magnetic nanoparticle enhanced gold nanorod biosensor upon specific cTnI binding, showing red-shift in the plasmon band maxima as a function of the target analyte concentration. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Mie G. Ann.Phys. 1908;25:377–445. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willets KA, Van Duyne RP. Annu.Rev.Phys.Chem. 2007;58:267–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KS, El Sayed MA. J.Phys.Chem.B. 2006;110:19220–19225. doi: 10.1021/jp062536y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain PK, Lee KS, El Sayed IH, El Sayed MA. J.Phys.Chem.B. 2006;110:7238–7248. doi: 10.1021/jp057170o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Link S, El Sayed MA. Annu.Rev.Phys.Chem. 2003;54:331–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.54.011002.103759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP. Nat.Mater. 2008;7:442–453. doi: 10.1038/nmat2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Ingram RS, Hostetler MJ, Pietron JJ, Murray RW, Schaaff TG, Khoury JT, Alvarez MM, Whetten RL. Science. 1998;280:2098–2101. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. Science. 2000;289:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch LR, Jackson JB, Lee A, Halas NJ, West JL. Anal.Chem. 2003;75:2377–2381. doi: 10.1021/ac0262210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elghanian R, Storhoff JJ, Mucic RC, Letsinger RL, Mirkin CA. Science. 1997;277:1078–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu C, Irudayaraj J. Anal.Chem. 2007;79:572–579. doi: 10.1021/ac061730d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu C, Nakshatri H, Irudayaraj J. Nano.Lett. 2007;7:2300–2306. doi: 10.1021/nl070894m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nusz GJ, Curry AC, Marinakos SM, Wax A, Chilkoti A. ACS Nano. 2009;3:795–806. doi: 10.1021/nn8006465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutter E, Fendler JH. Advanced Materials. 2004;16:1685–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreaden EC, Alkilany AM, Huang X, Murphy CJ, El Sayed MA. Chem.Soc.Rev. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer KM, Hafner JH. Chem.Rev. 2011;111:3828–3857. doi: 10.1021/cr100313v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petryayeva E, Krull UJ. Anal.Chim.Acta. 2011;706:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Chem.Rev. 2005;105:1547–1562. doi: 10.1021/cr030067f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain PK, Eustis S, El Sayed MA. J.Phys.Chem.B. 2006;110:18243–18253. doi: 10.1021/jp063879z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CD, Cheng SF, Chau LK, Wang CR. Biosens.Bioelectron. 2007;22:926–932. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marinakos SM, Chen S, Chilkoti A. Anal.Chem. 2007;79:5278–5283. doi: 10.1021/ac0706527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi Y, Kang T, Lee LP. Nano.Lett. 2009;9:85–90. doi: 10.1021/nl802511z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang L, Kwon HJ, Kang KA. Biotechnol.Bioeng. 2004;88:869–879. doi: 10.1002/bit.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan R, Vermesh O, Srivastava A, Yen BK, Qin L, Ahmad H, Kwong GA, Liu CC, Gould J, Hood L, Heath JR. Nat.Biotechnol. 2008;26:1373–1378. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stern E, Vacic A, Rajan NK, Criscione JM, Park J, Ilic BR, Mooney DJ, Reed MA, Fahmy TM. Nat.Nanotechnol. 2010;5:138–142. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nusz GJ, Marinakos SM, Curry AC, Dahlin A, Hook F, Wax A, Chilkoti A. Anal.Chem. 2008;80:984–989. doi: 10.1021/ac7017348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osaka T, Matsunaga T, Nakanishi T, Arakaki A, Niwa D, Iida H. Anal.Bioanal.Chem. 2006;384:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grigoriev D, Gorin D, Sukhorukov GB, Yashchenok A, Maltseva E, Mohwald H. Langmuir. 2007;23:12388–12396. doi: 10.1021/la700963h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pankhurst QA, Connolly J, Jones SK, Dobson J. Journal of Physics D-Applied Physics. 2003;36:R167–R181. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravindranath SP, Mauer LJ, Deb-Roy C, Irudayaraj J. Anal.Chem. 2009;81:2840–2846. doi: 10.1021/ac802158y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Y, Zhao C, Ren J, Qu X. Chem.Commun.(Camb.) 2009:1975–1977. doi: 10.1039/b818415a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arakaki A, Hideshima S, Nakagawa T, Niwa D, Tanaka T, Matsunaga T, Osaka T. Biotechnol.Bioeng. 2004;88:543–546. doi: 10.1002/bit.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez JM, Josephson L, O'Loughlin T, Hogemann D, Weissleder R. Nat.Biotechnol. 2002;20:816–820. doi: 10.1038/nbt720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaffe AS, Ravkilde J, Roberts R, Naslund U, Apple FS, Galvani M, Katus H. Circulation. 2000;102:1216–1220. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sau TK, Murphy CJ. Langmuir. 2004;20:6414–6420. doi: 10.1021/la049463z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikoobakht B, El-Sayed MA. Chem.Mater. 2003;15:1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy CJ, Sau TK, Gole AM, Orendorff CJ, Gao J, Gou L, Hunyadi SE, Li T. J.Phys.Chem.B. 2005;109:13857–13870. doi: 10.1021/jp0516846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wijaya A, Hamad-Schifferli K. Langmuir. 2008;24:9966–9969. doi: 10.1021/la8019205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staros JV, Wright RW, Swingle DM. Anal.Biochem. 1986;156:220–222. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grabarek Z, Gergely J. Anal.Biochem. 1990;185:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90267-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu WW, Falkner JC, Yavuz CT, Colvin VL. Chem.Commun. 2004:2306–2307. doi: 10.1039/b409601k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu WW, Chang E, Sayes CM, Drezek R, Colvin VL. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:4483–4487. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang D, Yuan R, Chai Y. J.Phys.Chem.B. 2006;110:11640–11646. doi: 10.1021/jp060950s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venge P, Johnston N, Lindahl B, James S. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2009;54:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajan GP, Zellweger R. J.Trauma. 2004;57:801–808. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000135157.93649.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCord J, Nowak RM, McCullough PA, Foreback C, Borzak S, Tokarski G, Tomlanovich MC, Jacobsen G, Weaver WD. Circulation. 2001;104:1483–1488. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.096336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antman EM, Tanasijevic MJ, Thompson B, Schactman M, McCabe CH, Cannon CP, Fischer GA, Fung AY, Thompson C, Wybenga D, Braunwald E. N.Engl.J.Med. 1996;335:1342–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610313351802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall WP, Ngatia SN, Van Duyne RP. J.Phys.Chem.C.Nanomater.Interfaces. 2011;115:1410–1414. doi: 10.1021/jp106912p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beccati D, Halkes KM, Batema GD, Guillena G, Carvalho de Souza, van Koten G, Kamerling JP. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1196–1203. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin K, Lu Y, Chen J, Zheng R, Wang P, Ming H. Opt.Express. 2008;16:18599–18604. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.018599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan J, Oliver R, Aguilar MI, Wu Y. Anal.Chem. 2008;80:8329–8333. doi: 10.1021/ac801301p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko S, Park TJ, Kim HS, Kim JH, Cho YJ. Biosens.Bioelectron. 2009;24:2592–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Sun Y, Wang J, Zhu X, Jia F, Cao Y, Wang X, Zhang H, Song D. Talanta. 2009;78:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Munir A, Zhu Z, Zhou HS. Anal.Chem. 2010;82:6782–6789. doi: 10.1021/ac100812c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoa XD, Kirk AG, Tabrizian M. Biosens.Bioelectron. 2007;23:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang L, Ren Y, Hong B, Kang KA. J.Biomed.Opt. 2006;11:021011. doi: 10.1117/1.2192529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang H, Huang S, Yuan S, Qu C, Chen Y, Xu Z, Liao B, Zeng Y, Chu PK. Anal.Chim.Acta. 2011;683:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haes AJ, Van Duyne RP. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 2002;124:10596–10604. doi: 10.1021/ja020393x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.