Abstract

On the basis of the studies that investigated the relationship between baseline clinic blood pressure (CBP) or home blood pressure (HBP) values and cardiovascular (CV) events, HBP has been reported to have a stronger prognostic ability. However, few studies have compared the prognostic ability of on-treatment CBP and HBP. The relationship between on-treatment HBP, measured twice in the morning and twice at bedtime, and CV events was investigated in over 20 000 patients in the HONEST (Home blood pressure measurement with Olmesartan Naive patients to Establish Standard Target blood pressure) Study, a prospective, 2-year observational study of treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker, olmesartan (OLM), in OLM-naive hypertensive patients. This report summarizes the study protocol, the baseline characteristics of the patients and CBP and HBP at 16 weeks. A total of 22 373 patients were registered across Japan; baseline data from 22 162 patients were collected. Baseline HBP (mean±s.d.) in the morning (the first measurement) was 151.6±16.4/87.1±11.8 mm Hg and at bedtime was 144.3±16.8/82.8±11.9 mm Hg, whereas CBP was 153.6±19.0/87.1±13.4 mm Hg. At 16 weeks, morning HBP was 135.0±13.7/78.8±9.9 mm Hg and bedtime HBP was 129.7±13.8/74.7±10.1 mm Hg, whereas CBP was 135.6±15.4/77.6±10.9 mm Hg. The follow-up period for each patient ends on 30 September 2012. The HONEST Study is expected to provide evidence showing the relationship between baseline and on-treatment CBP and HBP levels (both first and second measurements) and CV events.

Keywords: cardiovascular event, clinic blood pressure, home blood pressure, olmesartan

Introduction

Large-scale clinical studies have demonstrated that lowering clinic blood pressure (CBP) in hypertensive patients with antihypertensive drug therapy reduces the incidence of cardiovascular (CV) events.1, 2 Thus, strict management of blood pressure (BP) is recommended for hypertensive patients in the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH2009).3

Home BP (HBP) measurement has been reported to be more useful than CBP for the appropriate diagnosis, treatment and prediction of future CV events.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 HBP measurement is also widely accepted in Japan.10, 11

Systematic reviews by Stergiou et al.12 and Ward et al.13 confirmed that baseline HBP has a stronger prognostic ability for future CV events compared with CBP; however, few studies have investigated the relationship between on-treatment HBP and CV events in hypertensive patients.

Another important issue is the number of times that HBP should be measured on each occasion and which measurement should be used for clinical evaluation.14, 15

Olmesartan medoxomil (OLM), an angiotensin receptor blocker, potently binds to angiotensin II type 1 receptors.16 There are substantial data showing the antihypertensive effects of OLM on CBP, but little data are available on HBP levels.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

Therefore, we designed the HONEST (Home blood pressure measurement with Olmesartan Naive patients to Establish Standard Target blood pressure) Study, which collected and analyzed data for on-treatment HBP measured twice on each occasion, and CBP, and CV events during a 2-year follow-up period in patients on OLM-based treatment.

Methods

Study protocol

The protocol of the HONEST Study was submitted to and approved by the in-house ethical committee of Daiichi Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan before study commencement. This study was registered at http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/ (Trial registration reference number: UMIN000002567). The HONEST Study was carried out in registered medical institutions in compliance with Good Post-marketing Study Practice in Japan and internal regulations for clinical studies at each institution. The HONEST Study was planned as a large-scale prospective observational study following >20 000 patients with essential hypertension. Follow-up continued for 2 years after initiation of the study regardless of whether administration of OLM continued, unless death or withdrawal of consent occurred. The investigators contacted subjects who failed to visit the hospital at 16 weeks, 1 year and 2 years after initiation of the study to confirm their health status. The follow-up period ends on 30 September 2012. All adverse events were also recorded and reported by the study investigators.

Objectives

This study was designed to investigate: (1) the relationship between BP (morning HBP, bedtime HBP and CBP) and the incidence of CV events; (2) the relationship between the first or second measurement of HBP, or their average, and the incidence of CV events; and (3) the sustained 24-h BP-lowering effects of OLM-based antihypertensive therapy.

Patient recruitment

OLM-naive patients with essential hypertension who had recorded their morning HBP on at least 2 days within 28 days before taking OLM were eligible for inclusion (Table 1). Exclusion criteria are shown in Table 2. Each patient was informed of the purpose and methodology of the study, their right to withdraw from the study at any time, and the measures for privacy protection. After providing written informed consent and being prescribed OLM, patients were enrolled and data were collected through the internet using a central electronic data capturing system (PostMaNet; Fujitsu FIP, Tokyo, Japan). Physicians in several institutions were asked to select and register patients within 31 days of starting OLM therapy. The registration period was 1 year, from 1st October 2009 to 30th September 2010.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria of the HONEST Study.

| 1) Olmesartan (OLM)-naive patients with essential hypertension. |

| 2) Ambulatory outpatients who were able to visit the clinic unassisted. |

| 3) Patients from whom written informed consent was obtained. |

| 4) Patients whose blood pressure (BP) levels were measured in physician‘s office at least once within 28 days before starting OLM administration. |

| 5) Patients whose morning BP levels were measured by arm-cuff BP monitor at home at least twice on different days within 28 days before administration of OLM. |

Table 2. Exclusion criteria of the HONEST Study.

| 1) History of myocardial or cerebral infarction, cerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage, or stroke of unknown type (however, patients with transient ischemic attack were eligible) in the previous 6 months. |

| 2) Undergoing cardiovascular (CV) revascularization and hospitalization for heart failure in the previous 6 months. |

| 3) Scheduled CV revascularization at time of enrollment. |

| 4) Persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation. |

| 5) History of or concurrent cardiac diseases such as congenital or rheumatic heart disease, or moderate-to-severe cardiac valvulopathy. |

| 6) Unstable angina pectoris or severe arrhythmia. |

| 7) Pregnant or possibly pregnant. |

| 8) Inappropriate for long-term monitoring (for example, severe hepatic or renal dysfunction (patients under dialysis were ineligible) or critical diseases such as malignant neoplasm) as considered by physician. |

Antihypertensive drugs and concomitant drugs

No restriction was placed on antihypertensive drug treatment. OLM (generally 10 or 20 mg day−1) was administered at each participating physician's discretion. Selection of target BP and use of concomitant drugs was left to the discretion of individual physicians.

BP measurements

The CBP was measured according to the usual methods of each institution; no recommendations or training were provided with respect to CBP measurement. CBP was reported once before starting OLM therapy and at 4 weeks, 16 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months and 24 months after the initiation of OLM therapy.

The patients who already owned electronic arm-cuff devices based on the cuff-oscillometric method were registered. All such devices available in Japan have been validated and approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. After starting OLM therapy, patients were asked to measure their HBP twice in the morning and twice at bedtime on 2 different days at each measurement point according to JSH2009 (in the morning: within 1 h after waking up, after urination, before taking morning medications, before eating breakfast and after 1- to 2-min resting in a sitting position; at bedtime: before retiring and after 1- to 2-min resting in a sitting position). Patients were asked to document the BP values on a sheet of paper and report them to their physician. Morning HBP was recorded on 2 days within the 28 days before starting OLM therapy. After the start of OLM therapy, the HBP values were reported at 1 week, 4 weeks, 16 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months and 24 months. The HBP at each measurement point is defined as an averaged value over 2 days.

End point evaluation

The primary and secondary end points of the study are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Each event review committee consisted of ⩾2 members and was responsible for the confirmation and classification of the events under blinded conditions (see Appendix). The definition of events is presented in Table 4.23, 24

Table 3. End points of the HONEST Study.

| Primary end point |

| Time from start of treatment to first occurrence of major cardiovascular (CV) events defined as cerebral infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke of unknown type, myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization procedures for angina pectoris or sudden death. |

| Secondary end points |

| 1) Time from start of treatment to first occurrence of major event including major CV events, hospital admission for angina pectoris or heart failure, aortic dissection, arteriosclerosis obliterans, end-stage renal disease, doubling of serum creatinine concentration and death from any cause. |

| 2) Change in home and clinic blood pressure levels. |

| 3) Safety. |

Table 4. Definition of events of the HONEST Study.

| (1) Stroke |

| ‘Stroke' is recorded if patients have classic neurologic symptoms for ⩾24 h and their computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings are consistent with clinical types of stroke. Stroke is classified as cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage or unclassified stroke. Cerebral infarction is subclassified as atherothrombotic cerebral infarction, cardiogenic cerebral infarction, lacunar infarction and unclassified cerebral infarction depending on Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment classification.23 |

| Death within 28 days of the onset of stroke is recorded as fatal stroke; all other cases are non-fatal stroke. |

| (2) Myocardial infarction |

| ‘Myocardial infarction' is recorded based on overall judgment of the presence of symptoms of possible acute myocardial infarction, as well as specific findings from biochemical tests, electrocardiography, and so on. Death within 28 days of the onset of myocardial infarction is recorded as fatal myocardial infarction; other cases are non-fatal myocardial infarction. |

| (3) Coronary revascularization for angina pectoris |

| ‘Coronary revascularization for angina pectoris' is recorded when coronary revascularization (for example, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft) is needed for suspected myocardial infarction or diagnosed angina pectoris. |

| (4) Hospitalization for angina pectoris |

| ‘Hospitalization for angina pectoris' is recorded when patients are admitted to hospital for treatment of angina pectoris, except when coronary revascularization is being done. |

| (5) Hospitalization for heart failure |

| ‘Hospitalization for heart failure' is recorded when patients are admitted to hospital for treatment of heart failure. Heart failure is diagnosed when patients meet ⩾2 major criteria for heart failure in the Framingham Heart Study,24 1 major criteria and ⩾2 minor criteria, or New York Heart Association classification of heart function III or IV. |

| (6) Sudden death ‘Sudden death' is defined as an unexpected death within 24 h of onset, without external causes. |

| (7) Aorta dissection |

| ‘Aorta dissection' is defined as a tear in the aortic intima allowing blood to enter the aortic media, confirmed by computed tomography, echocardiography or magnetic resonance angiography, and so on. |

| (8) Arteriosclerosis obliterans |

| ‘Arteriosclerosis obliterans' is recorded when patients correspond to classes II–IV of the Fontaine classification, have an ankle–brachial index of <0.9 or have sites of obstruction (stenosis) confirmed by echocardiography, magnetic resonance angiography or angiography. |

| (9) End-stage renal disease |

| ‘End-stage renal disease' is recorded when patients have serum creatinine concentration ⩾5.0 mg dl−1 (except for temporary increases), need chronic dialysis or need renal transplantation. |

| (10) Doubling of serum creatinine |

| ‘Doubling of serum creatinine' is defined as persistent doubling of baseline serum creatinine and a serum creatinine ⩾2.0 mg dl−1. |

| (11) All death. |

Sample size determination

On the basis of the previous study results,25, 26 we made the following presumptions: the incidence of primary CV events in this study was assumed to be 7.8/1000 person years. The risk ratio for occurrence of the events was assumed to be 1 (reference):1.25:2:3:5, when systolic BP is divided into five groups by 10 mm Hg increments and the reference group (that is, risk=1) is defined as having either HBP <125 mm Hg (measured in the morning or at bedtime) or CBP <130 mm Hg. Under this presumption, a sample size of 20 000 subjects is required to obtain power ⩾80% with α=0.05 (two-tailed) to test linear hypotheses regarding the regression parameters by the Cox proportional hazards model.

Statistical analysis

Planned statistical analyses in the HONEST Study are as follows: changes over time in systolic BP, diastolic BP and pulse rate will be compared with baseline values using the Dunnett–Hsu test to adjust for multiple comparisons. The Cox proportional hazards model will be used to investigate the relationship between the incidence of events and on-treatment BP as a time-dependent covariate. The first measurement, the second measurement, and the mean of the first and second measurements will be compared with examination, which value had the strongest prognostic ability. All statistical tests will be two-sided using a level of significance of 0.05.

For data related to baseline characteristics and BP levels in this article, values are expressed as the mean±s.d. or percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Release 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient number and disposition

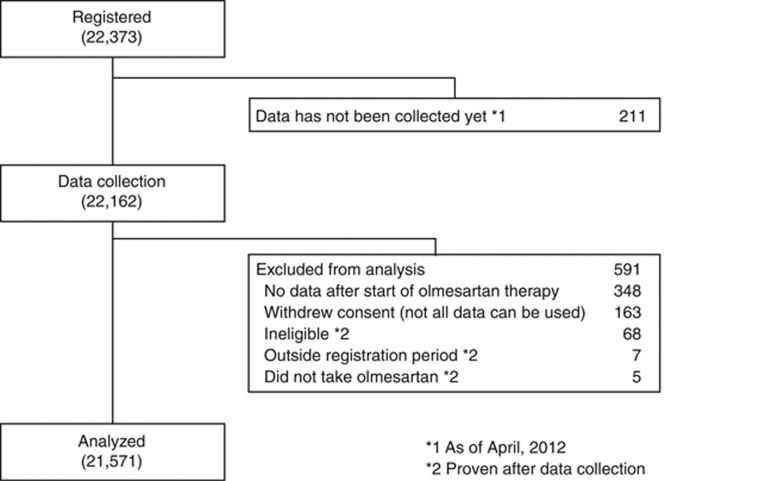

Patient disposition is shown in Figure 1. A total of 22 373 patients from 3039 medical institutions across Japan were registered; baseline data for 22 162 patients were collected. A total of 591 patients were excluded for the reasons shown in Figure 1. Our current analysis included data from 21 571 patients.

Figure 1.

Profile of the HONEST (Home blood pressure measurement with Olmesartan Naive patients to Establish Standard Target blood pressure) Study till April 2012.

Baseline characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 5. The mean age of the patients was 64.8 years; 50.6% of patients were female. In total, 10.5% had a history of stroke, percutaneous coronary revascularization and myocardial infarction; 50.2% were receiving antihypertensive drugs. The prevalence of dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus was 44.5% and 20.4%, respectively.

Table 5. Baseline characteristics.

| No. of patients (%) or mean±s.d. (n=21 571) | |

|---|---|

| Women | 10 906 (50.6) |

| Age (years) | 64.8±11.9 |

| (min–max) | (16–100) |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) (n=14 722) | 24.31±3.71 |

| Alcohol drinkers | 3474 (16.1) |

| Current smokers | 2652 (12.3) |

| Previous antihypertensive treatment | 10 834 (50.2) |

| History | |

| Cerebro- or cardiovascular disease | 2262 (10.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1430 (6.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 975 (4.5) |

| Complications | |

| Dyslipidemia | 9592 (44.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4409 (20.4) |

| Cardiac disease | 2004 (9.3) |

| Renal disease | 1474 (6.8) |

| Hepatic disease | 1429 (6.6) |

| Main concomitant drugs | |

| Antidyslipidemic drug | 5872 (27.2) |

| Antidiabetic drug | 2956 (13.7) |

| Anticoagulant or antiplatelet drug | 2596 (12.0) |

| Lipid | |

| Total cholesterol (mg dl−1) | 202.6±36.0 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg dl−1) | 118.8±31.0 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg dl−1) | 58.5±15.7 |

| Triglycerides (mg dl−1) | 133.4±86.3 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg dl−1) | 106.0±29.8 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (NGSP) (%) | 6.20±1.08 |

| Creatinine (mg dl−1) | 0.79±0.32 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml min−1 per 1.73m2) | 72.4±20.2 |

Compliance with measurement conditions in JSH2009 occurred in 82.1% and 80.7% of the patients in the morning and at bedtime, respectively.

White-coat hypertension, defined as systolic CBP ⩾140 mm Hg and systolic HBP <135 mm Hg (at the first measurement) in the morning, was found in 5.6% of patients, and masked hypertension, defined as systolic CBP <140 mm Hg and systolic HBP ⩾135 mm Hg in the morning, was found in 11.8% at baseline. Those with white-coat hypertension and masked hypertension included patients both receiving and not receiving antihypertensive treatment.

Antihypertensive drugs

The administration status of antihypertensive drugs is shown in Table 6. At baseline, 38.7% of patients were receiving antihypertensive agents in addition to OLM. The dose of OLM (mg) and the number of antihypertensive drugs, including OLM, increased from 18.2±7.0 and 1.5±0.7 at the start of investigation to 18.7±8.4 and 1.6±0.8 at 16 weeks.

Table 6. Antihypertensive drugs used.

| Baseline (n=21 571) | 16 weeks (n=21 571) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of antihypertensive drugs (including olmesartan) | 1.5±0.7 | 1.6±0.8 |

| Antihypertensive drugs other than olmesartan, n (%) | 8354 (38.7) | 9663 (44.8) |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 7306 (33.9) | 8447 (39.2) |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 1288 (6.0) | 1397 (6.5) |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 971 (4.5) | 1414 (6.6) |

| α-Blocker, n (%) | 438 (2.0) | 513 (2.4) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, n (%) | 311 (1.4) | 311 (1.4) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, n (%) | 165 (0.8) | 167 (0.8) |

BP levels

BP levels at baseline and 16 weeks after OLM administration are presented in Table 7. BP at 16 weeks is presented to show BP control status, similar to a second baseline. The first measurement of morning HBP at baseline was 151.6±16.4/87.1±11.8 mm Hg; the second measurement was 150.1±16.2/86.6±11.4 mm Hg. The first measurement of bedtime HBP was 144.3±16.8/82.8±11.9 mm Hg, and the second measurement was 143.8±16.8/82.6±11.5 mm Hg, whereas the CBP was 153.6±19.0/87.1±13.4 mm Hg. The first measurement of morning HBP at 16 weeks was 135.0±13.7/78.8±9.9 mm Hg; the second measurement was 133.0±13.5/78.1±9.9 mm Hg. The first HBP measurement at bedtime was 129.7±13.8/74.7±10.1 mm Hg; the second measurement was 127.6±13.7/73.9±10.0 mm Hg, whereas the CBP was 135.6±15.4/77.6±10.9 mm Hg.

Table 7. Blood pressure at baseline and after 16 weeks of olmesartan therapy.

|

Baseline |

16 weeks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | n | Mean | s.d. | n | Mean | s.d. |

| Home morning first measurement | ||||||

| Systolic | 21 569 | 151.6 | 16.4 | 19 324 | 135.0 | 13.7 |

| Diastolic | 21 569 | 87.1 | 11.8 | 19 317 | 78.8 | 9.9 |

| Home morning second measurement | ||||||

| Systolic | 7721 | 150.1 | 16.2 | 15 392 | 133.0 | 13.5 |

| Diastolic | 7720 | 86.6 | 11.4 | 15 390 | 78.1 | 9.9 |

| Home bedtime first measurement | ||||||

| Systolic | 11 639 | 144.3 | 16.8 | 17 116 | 129.7 | 13.8 |

| Diastolic | 11 638 | 82.8 | 11.9 | 17 115 | 74.7 | 10.1 |

| Home bedtime second measurement | ||||||

| Systolic | 5848 | 143.8 | 16.8 | 14 571 | 127.6 | 13.7 |

| Diastolic | 5848 | 82.6 | 11.5 | 14 571 | 73.9 | 10.0 |

| Clinic | ||||||

| Systolic | 21 571 | 153.6 | 19.0 | 20 202 | 135.6 | 15.4 |

| Diastolic | 21 571 | 87.1 | 13.4 | 20 195 | 77.6 | 10.9 |

Differences between the first and second measurement of morning systolic HBP at baseline and 16 weeks after OLM administration were calculated in patients who measured both a first and second morning HBP at baseline or at 16 weeks. Differences at baseline representing increases that were >10 mm Hg, 5< to 10 mm Hg and 0< to 5 mm Hg as well as decreases 0–<5 mm Hg, 5–<10 mm Hg, 10–<15 mm Hg and ≥15 mm Hg were 2.1, 4.4, 19.8, 42.1, 20.0, 7.4 and 4.2%. Differences at 16 weeks were 1.8, 5.3, 22.7, 43.1, 18.9, 5.7 and 2.5%.

Of those whose systolic HBP was measured twice, the proportion of patients who had a systolic BP 150 mm Hg or more at the first HBP measurement and a reduction of 15 mm Hg or more at the second HBP measurement was 3.3% at baseline and 1.0% at 16 weeks.

Discussion

Several studies have reported a stronger prognostic ability of HBP compared with CBP. However, these studies were based on the assessment of baseline HBP and did not have information on variables possibly influencing the outcome (changes in treatment, introduction of antihypertensive drug treatments and BP achieved during follow-up).4, 5, 6, 7, 8 BP status could change during the follow-up period.27 Thus, this study was planned to investigate the relationship between on-treatment HBP and CV events. Shimada et al.28 reported that the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) of CV events in patients with masked hypertension defined on the basis of BP values measured after 6 months of angiotensin receptor blocker-based therapy was 2.00 (0.67–5.98). As the number of events was low, a significant increase in the relative risk of CV events was not detected. Another study, the HOMED-BP study, was conducted to establish the relationship between HBP and CV events in Japan, and the results were recently published.29

No global consensus has been reached on how many measurements should be made on each occasion. In the European Society of Hypertension guidelines,30 two measurements on each occasion are recommended, and in a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association,31 three measurements are recommended. JSH20093 recommended one or more measurements on one occasion. The Ohasama study,4 the HOMED-BP study29 and the PAMELA study6 used one measurement on each occasion. HBP was measured twice on each occasion in the Finn–Home study7 and the Didima outcome study.8 Thus, evidence is needed to determine the number of HBP measurements on each occasion for clinical evaluation.

Some limitations of the HONEST Study should be considered.

Patients who had recorded a morning HBP on at least 2 days within the 28 days before taking OLM were recruited in the HONEST Study. Thus, some patients did not have a second baseline HBP value.

In this analysis, at 16 weeks after OLM administration, most of the patients had two HBP values in the morning and at bedtime.

The HONEST Study is a prospective observational study without a comparator group and is not a randomized controlled study. The selection of target CBPs and HBPs and the use of concomitant drugs were left to the discretion of individual physicians. Despite such limitations, the results of the HONEST Study are expected to provide valuable ‘real-world' information about the relationship between baseline and on-treatment home and clinic BP values and CV events in over 20 000 Japanese hypertensive patients receiving OLM-based antihypertensive therapy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the numerous investigators, fellows, nurses and research coordinators at each of the study sites who have participated in the HONEST Study. We also gratefully acknowledge their contribution to the study of these subjects.

Appendix

Study organization

General advisors: KS (chair), KK. Medical advisors: KS, KK, IS, TK. Statistical advisor: ST. Event review committee (cerebrovascular events): Yasuhisa Kitagawa (chair), Yasuhiro Hasegawa. Event review committee (CV events): KS (chair), Atsushi Hirayama. Event review committee (other events): IS (chair), TK, KK. Administrative office: Post-Marketing Study Department, Daiichi-Sankyo.

Drs IS, KK, TK, ST and KS have a competing interest to declare. NZ, KH and FK are employees of Daiichi Sankyo. This study was supported with funding for data collection and statistical analysis by Daiichi Sankyo.

References

- Zanchetti A, Mancia G, Black HR, Oparil S, Waeber B, Schmieder RE, Bakris GL, Messerli FH, Kjeldsen SE, Ruilope LM. Facts and fallacies of blood pressure control in recent trials: implications in the management of patients with hypertension. J Hypertens. 2009;27:673–679. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283298ea2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecchia P, Gentile G, Angeli F, Mazzotta G, Mancia G, Reboldi G. Influence of blood pressure reduction on composite cardiovascular endpoints in clinical trials. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1356–1365. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328338e2bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H. Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009) Hypertens Res. 2009;32:3–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Kato J, Kikuchi N, Nishiyama A, Aihara A, Sekino M, Kikuya M, Ito S, Satoh H, Hisamichi S. Home blood pressure measurement has a stronger predictive power for mortality than does screening blood pressure measurement: a population-based observation in Ohasama, Japan. J Hypertens. 1998;16:971–975. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrie G, Chatellier G, Genes N, Clerson P, Vaur L, Vaisse B, Menard J, Mallion JM. Cardiovascular prognosis of ‘masked hypertension' detected by blood pressure self-measurement in elderly treated hypertensive patients. JAMA. 2004;291:1342–1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, Mancia G. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777–1783. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160923.04524.5B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiranen TJ, Hänninen MR, Johansson J, Reunanen A, Jula AM. Home-measured blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than office blood pressure: the Finn-Home study. Hypertension. 2010;55:1346–1351. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.149336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiou GS, Nasothimiou EG, Kalogeropoulos PG, Pantazis N, Baibas NM. The optimal home blood pressure monitoring schedule based on the Didima outcome study. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:158–164. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiou GS, Bliziotis IA. Home blood pressure monitoring in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension: a systematic review. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:123–134. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara T, Ohkubo T, Fukunaga H, Kobayashi M, Satoh M, Metoki H, Asayama K, Inoue R, Kikuya M, Mano N, Miyakawa M, Imai Y. Practice and awareness of physicians regarding home blood pressure measurement in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:428–434. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Nomura M, Hirose H, Kawabe H. Use of home blood pressure monitoring and exercise, diet and medication compliance in Japan. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:210–213. doi: 10.3109/10641961003667922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiou GS, Siontis KC, Ioannidis JP. Home blood pressure as a cardiovascular outcome predictor: it's time to take this method seriously. Hypertension. 2010;55:1301–1303. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, Heneghan C. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449–456. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834e4aed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe H, Saito I. Which measurement of home blood pressure should be used for clinical evaluation when multiple measurements are made. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1369–1374. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32811d69f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Jula AM. Prognostic value of the variability in home-measured blood pressure and heart rate: the Finn-Home Study. Hypertension. 2012;59:212–218. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.178657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike H, Konse T, Sada T, Ikeda T, Hyogo A, Hinman D, Saito H, Yanagisawa H. Olmesartan medoxomil, a novel potent angiotensin II blocker. Annu Rep Sankyo Res Lab. 2003;55:1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Oparil S, Williams D, Chrysant SG, Marbury TC, Neutel J. Comparative efficacy of olmesartan, losartan, valsartan, and irbesartan in the control of essential hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2001;3:283–291, 318. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2001.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Kushiro T, Hirata K, Sato Y, Kobayashi F, Sagawa K, Hiramatsu K, Komiya M. The use of olmesartan medoxomil as monotherapy or in combination with other antihypertensive agents in elderly hypertensive patients in Japan. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Kushiro T, Ishikawa M, Matsushita Y, Sagawa K, Hiramatsu K, Komiya M. Early antihypertensive efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:930–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushiro T, Saito I, Hirata K, Ishikawa M, Yamashita T, Matsushita Y, Sagawa K, Hiramatsu K, Komiya M. Blood pressure-lowering effects of angiotensin receptor antagonist monotherapy and in combination with other anti-hypertensive drugs in primary care settings in Japan. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009;31:127–141. doi: 10.1080/10641960802621275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Eguchi K, O'Rourke MF, Ishikawa J, Miyashita H, Shimada K, Kario K. Differential effects between a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic when used in combination with angiotensin II receptor blocker on central aortic pressure in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;54:716–723. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa M.Comparative efficacy of angiotensin II receptor blockers on early morning blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension: final report Ther Res 2009301879–1882.In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushiro T, Mizuno K, Nakaya N, Ohashi Y, Tajima N, Teramoto T, Uchiyama S, Nakamura H. Management of Elevated Cholesterol in the Primary Prevention Group of Adult Japanese Study Group. Pravastatin for cardiovascular event primary prevention in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension in the Management of Elevated Cholesterol in the Primary Prevention Group of Adult Japanese (MEGA) Study. Hypertension. 2009;53:135–141. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto K, Fujita T, Ito S, Naritomi H, Ogihara T, Shimada K, Tanaka H, Yoshiike N. J-HEALTH Study Committees. Impact of blood pressure control on cardiovascular events in 26,512 Japanese hypertensive patients: the Japan Hypertension Evaluation with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan Therapy (J-HEALTH) study, a prospective nationwide observational study. Hypetens Res. 2008;31:469–478. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Bombelli M, Facchetti R, Madotto F, Quarti-Trevano F, Polo Friz H, Grassi G, Sega R. Long-term risk of sustained hypertension in white-coat or masked hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54:226–232. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Fujita T, Ito S, Naritomi H, Ogihara T, Shimamoto K, Tanaka H, Yoshiike N. The importance of home blood pressure measurement for preventing stroke and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive patients: a sub-analysis of the Japan Hypertension Evaluation with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan Therapy (J-HEALTH) study, a prospective nationwide observational study. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1903–1911. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, Obara T, Inoue R, Kikuya M, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Imai Y.on behalf of Hypertension Objective Treatment Based on Measurement by Electrical Devices of Blood Pressure (HOMED-BP) investigators. Cardiovascular outcomes in the first trial of antihypertensive therapy guided by self-measured home blood pressure Hypertens Res 2012351102–1110.22895063 [Google Scholar]

- Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Manolis A, Mengden T, O'Brien E, Ohkubo T, Padfield P, Palatini P, Pickering T, Redon J, Revera M, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, Tisler A, Waeber B, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1505–1526. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328308da66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, Goff D. American Heart Association; American Society of Hypertension; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:10–29. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.189010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]