Abstract

Context:

Patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy may have an increased incidence of low-energy subtrochanteric and diaphyseal (SD) femoral fractures. However, the incidence and risk factors associated with these fractures have not been well defined.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to determine the incidence of and risk factors for low-energy SD fractures in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF).

Design:

Low-energy SD fractures were identified from a review of radiographic reports obtained between 1986 and 2010 in women in the SOF. Among the SD fractures, pathological, periprosthetic, and traumatic fractures were excluded. We assessed risk factors for SD fractures as well as risk factors for femoral neck (FN) and intertrochanteric (IT) hip fractures using both age-adjusted and multivariate time-dependent proportional hazards models. During this follow-up, only a small minority had ever used bisphosphonates.

Results:

Forty-five women sustained low-energy subtrochanteric/diaphyseal femoral fractures over a total follow-up of 140 000 person-years. The incidence of SD fracture was 3.2 per 10 000 person-years compared with a total hip fracture incidence of 110 per 10 000 person-years. A total of about 12% of women reported bisphosphonate use at 1 or more visits. In multivariate analyses, age, total hip bone mineral density (BMD), bisphosphonate use, and history of diabetes emerged as independent risk factors for SD fractures. Risk factors for FN and IT fractures included age, BMD, and history of falls or prior fractures. Bisphosphonate use was protective against FN fractures, whereas there was an increased risk of SD fractures (hazard ratio 2.58, P = .049) with bisphosphonate use after adjustment for other risk factors for fracture.

Conclusions:

In SOF, low-energy SD fractures were rare occurrences, far outnumbered by FN and IT fractures. Typical risk factors were associated with FN and IT fractures, whereas only age, total hip BMD, and history of diabetes were independent risk factors for SD fractures. In addition, bisphosphonate use was a marginally significantly predictor although the SOF study has limited ability to assess this association.

Epidemiological studies and case reports of low-energy subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femoral fractures with specific radiographic features, in patients on bisphosphonate therapy, have brought attention to the epidemiology and pathophysiology of subtrochanteric fractures (1–5). Incidence of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal fractures in bisphosphonate-naïve patients has been studied in the general population prior to the introduction of bisphosphonates (6–11). These studies, as well as others (12), have shown higher incidence with age in older women. More recently, large epidemiological studies that have been focused on bisphosphonate use (13–17) have also examined other risk factors (eg, corticosteroid use, diabetes, etc), but a consistent risk factor profile has not been established. Furthermore, there are no prospective studies that have examined risk factors for subtrochanteric fractures including bone mineral density (BMD). In fact, it is uncertain whether the traditional risk factors for common hip fractures such as BMD, body mass index (BMI), falls, previous fractures, and estrogen use are even predictors of these fractures.

Given the controversies that have arisen on this topic, the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the International Osteoporosis Foundation have established 2 independent task forces that, in their respective position papers, have highlighted the need for future studies that identify the risk factors for subtrochanteric fractures (1, 18).

The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) is a prospective cohort study begun in 1986 in which 9704 nonblack women over age 65 years were recruited from 4 academic centers and were followed up prospectively for incident fractures. The vast majority of follow-up occurred prior to the introduction of bisphosphonates or among women who did not use bisphosphonates. Almost 2000 hip fractures have occurred in this cohort between the baseline examination and 2009 (mean follow-up 14.7 ± 6.0 years). We used documentation of incident hip fractures together with risk factor information to determine the incidence of and risk factors for subtrochanteric, femoral neck, and intertrochanteric fractures in this population of primarily bisphosphonate-naïve women.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

SOF is a large multicenter prospective cohort study of risk factors for fracture in 9704 community-dwelling ambulatory white women aged 65 years or older, who were enrolled between September 1986 and October 1988 (19). Women were recruited from population-based listings in 4 regions of the United States: Baltimore County, MD; Minneapolis, MN; Portland, OR; and the Monongahela Valley near Pittsburgh, PA. African Americans were initially excluded because of their lower rate of hip fracture. Other exclusion criteria included history of bilateral hip replacement and inability to walk without assistance. All women provided written informed consent. Approval was obtained from the institutional review boards at each site.

Clinic visits

SOF methods have been previously described (19). Briefly, at the baseline examination, all participants completed a questionnaire and interview and underwent a physical examination. Some of the variables that were collected included age, height, weight, history of fracture, maternal history of hip fracture, history of falls, smoking status, medical comorbidities, and medication use.

All active surviving participants were invited to participate in 7 follow-up clinic examinations over the course of the study. Demographic and risk factor variables that were updated at follow-up examinations included history of falls, history of fracture, medications, and medical comorbidities. At the year 2 and 4 examinations, queries about specific medications were included for which details varied. Detailed information about estrogen use including duration, dose, and mode of administration was collected. At the year 6, 8, 10, and 16 examinations occurring between 1992 and 2004, participants were queried about current use of all medications. Participants were asked to bring all current prescription and over-the-counter medications that had been used in the last 30 days, and these were entered into an electronic medication inventory system. However, with the exception of estrogen use, dose and duration of use for current medications, including bisphosphonates, was not assessed. We defined use of bisphosphonates as use of alendronate, pamidronate, risedronate, or ibandronate, as they became available, but not etidronate. Estrogen use was limited to oral estrogen. Glucocorticoid use included use of oral steroids only. Diabetes was ascertained based on self-report or, for year 8 and later visits, the reported use of an antidiabetic medication. Blood glucose assays were not available.

Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans of the hip were first performed at the year 2 examination between November 1988 and December 1990 (Hologic 1000; Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts). Details of the measurement method and densitometry quality control procedures have been published elsewhere (20). The right proximal femur was scanned except in the case of right hip replacement or severe degenerative change. DXA hip scans were repeated at the year 6, 8, 10, and 16 examinations (1992–2004) for a median of 2 measurements per participant and a maximum of 5 measurements.

Fracture reporting

Participants were contacted by postcard every 4 months, with telephone follow-up for nonresponders, to ask whether they had sustained a fracture. They were also asked to notify the local clinical center as soon as possible after any fracture. Follow-up contacts were greater than 95% complete. After receiving a report of a fracture, clinic staff interviewed participants about the type of fracture and how it occurred. Copies of radiological reports were obtained for all nonvertebral fractures. Incident nonvertebral fractures were physician adjudicated from radiology reports by a central adjudicator. During the study, all hip and femur fractures were classified into 1 of 6 categories by anatomical region: femoral neck (FN), intertrochanteric region (IT), femur, hip, acetabular, or other region of the hip (21). However, a specific category for subtrochanteric fractures was not originally used and such fractures could have been classified as in the femur, intertrochanteric, or hip categories.

Fracture re-review

To identify subtrochanteric and diaphyseal (SD) fractures, all radiology reports of hip and femur fractures that occurred in the intertrochanteric region or below were re-reviewed by 1 of 2 orthopedic surgery residents (M.K. and R.W.) and whether any met the required criteria. Femoral neck fracture radiology reports were not re-reviewed. Available for review were emergency department notes, radiology reports, and, in some instances, orthopedic operative and clinic reports. No radiographs were available for review. From the description of the fracture in the radiology and operative reports, the fractures were reviewed to determine whether any should be reclassified as SD.

Subtrochanteric fractures were defined as those with fracture lines in the region starting at the lesser trochanter and extending distal to include the proximal metaphyseal flare. Fractures that extended proximally into the intertrochanteric region were classified as intertrochanteric, not subtrochanteric fractures. Diaphyseal femur fractures were defined as those occurring distal to the proximal metaphyseal flare and proximal to the distal metaphyseal flare. After the individual re-review had been completed, both surgeons again reviewed the fractures that had been reclassified as SD and reached consensus on whether each fracture met the inclusion criteria. Pathological fractures, duplicate entries, periprosthetic fractures, and fractures occurring in the context of major trauma were excluded.

Analysis

These analyses included 3 categories of hip fractures: SD (based on orthopedic surgeon re-review), femoral neck (based on the original SOF classification), and intertrochanteric (based on the original SOF classification minus those reclassified as SD by re-review). Participants were included in more than 1 fracture group if they sustained multiple types of fractures. Baseline characteristics were summarized for each of the 3 fracture types as well as the overall study population.

Time-dependent proportional hazards models for time to first fracture within each type of hip fracture were used to determine the relative hazard of each fracture type associated with various risk factor variables. Variables in the analysis were age, BMI, height, current estrogen use, bisphosphonate use, glucocorticoid use, exercise (blocks walked for exercise per day), falls in the previous year, history of fracture, prevalent vertebral fracture, total hip BMD, and history of diabetes mellitus. In the time-dependent model, the value of each risk factor was updated at any time that new data were available. If data were missing during follow-up, the last observation from an earlier measurement was carried forward. When no follow-up values were available (ie, height at enrollment, maternal history of fracture), the baseline values were used throughout the analysis.

We first performed age-adjusted analyses on a number of risk factor variables to determine their association with each of the 3 types of fractures. In the multivariable analysis, we used the same set of variables for all 3 fracture types and included any variable that was significant (P < .05) in age-adjusted analyses for any of the 3 fracture types.

Results

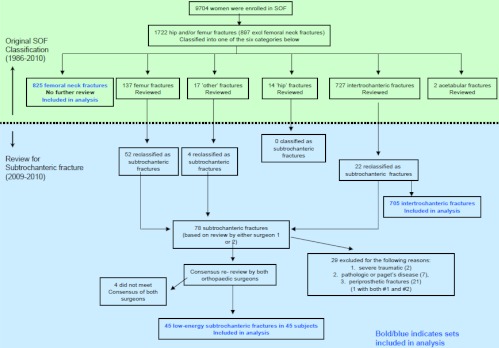

A total of 1722 hip and femur fractures were reported from 1986 to 2009. By original adjudication, 825 were classified as FN, 727 as IT, 137 as femur, 14 as (unspecified) hip, 2 as acetabular, and 17 as other hip fractures (Figure 1). After re-review of all hip and femur (except FN) fractures (n = 897 fractures), a total of 78 SD fractures were identified by at least 1 of the 2 reviewers. Upon consensus review, 4 were eliminated, leaving 74 (Figure 1). After excluding periprosthetic (n = 21), pathological (n = 7), and major trauma fractures (n = 2), 45 fractures in 45 women met the criteria for low-energy SD femur fractures and were included in the statistical analysis. Of these, 22 (49%) were originally classified as femur fractures, 19 (42%) as intertrochanteric fractures, and 4 (9%) as other hip fractures. We found no women with more than a single SD fracture.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the hip fracture re-review performed in 2009–2010 to identify low-energy SD fractures. Bold blue indicates sets included in the analyses.

After review and excluding multiple fractures of the same type in an individual, there were a total of 45 women with SD fractures, 768 with FN fractures, and 642 with IT fractures. A total of 76 women had distal metaphyseal fractures (not included in this analysis). Clinical characteristics at baseline are shown across each of the 3 fracture types and in the overall study population (Table 1). Participants who sustained SD fractures were older than the study population, with a mean baseline age of 74.2 ± 6.8 years compared with 71.7 ± 5.3 years for the overall population, as were patients who sustained FN and IT fractures (FN 72.7 ± 5.3 years; IT 74.0 ± 5.7 years). BMD was lower in those with FN or IT fractures and intermediate in those with SD fractures. Other baseline clinical characteristics by fracture type are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Fracture Type

| Unit | Study Population | Femoral Neck | Intertrochanteric | Subtrochanteric | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 9704 | 768 | 642 | 45 | |

| Adjusted current age | y | 71.7 ± 5.3 | 72.7 ± 5.3 | 74.0 ± 5.7 | 74.2 ± 6.8 |

| Total hip BMD | g/cm2 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.70 ± 0.11 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.73 ± 0.12 |

| Femoral neck BMD | g/cm2 | 0.65 ± 0.11 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.09 | 0.62 ± 1.19 |

| Weight | kg | 67.1 ± 12.5 | 64.4 ± 11.0 | 64.2 ± 11.5 | 66.7 ± 10.3 |

| Height | cm | 159.3 ± 6.0 | 160.0 ± 6.1 | 158.4 ± 6.4 | 158.1 ± 7.1 |

| BMI | kg/m2 | 26.4 ± 4.6 | 25.1 ± 3.9 | 25.6 ± 4.3 | 26.8 ± 4.2 |

| Any fracture after age 50 y | Yes | 3580 (36.9%) | 349 (45.4%) | 311 (48.4%) | 20 (44.4%) |

| Hip fracture after age 50 y | Yes | 185 (1.9%) | 21 (2.7%) | 19 (3.0%) | 2 (4.4%) |

| Maternal hip fracture after age 50 y | Yes | 993 (10.2%) | 118 (15.4%) | 92 (14.3%) | 5 (11.1%) |

| Fall within last year | Yes | 2915 (30.1%) | 253 (33.0%) | 201 (31.3%) | 14 (31.1%) |

| Smoker | Current | 967 (10.0%) | 79 (10.3%) | 64 (10.0%) | 5 (11.1%) |

| Past | 2863 (29.6%) | 229 (29.8%) | 173 (27.0%) | 10 (22.2%) | |

| Never | 5843 (60.4%) | 460 (59.9%) | 404 (63.0%) | 30 (66.7%) | |

| History of oral estrogen use | Current | 1331 (13.9%) | 104 (13.7%) | 65 (10.2%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Past | 2621 (27.4%) | 215 (28.3%) | 154 (24.3%) | 16 (36.4%) | |

| Never | 5616 (58.7%) | 441 (58.0%) | 416 (65.5%) | 26 (59.1%) | |

| History of corticosteroid use | Current | 191 (2.0%) | 21 (2.8%) | 12 (1.9%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Past | 931 (9.8%) | 76 (10.1%) | 51 (8.2%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Never | 8395 (88.2%) | 659 (87.2%) | 561 (89.9%) | 43 (95.6%) | |

| History of diabetes | Yes | 680 (7.0%) | 40 (5.2%) | 52 (8.1%) | 5 (11.4%) |

Clinical characteristics that were updated at each examination included history of falls, medication use, and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus as shown in Table 2. The values in the table are those that were reported at least once during follow-up.

Table 2.

Follow-Up Characteristics by Fracture Type (Cumulative Exposure to Risk Factors in All the Study Subjects According to Fracture Type Subgroups)

| Study Population | Femoral Neck | Intertrochanteric | Subtrochanteric | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean length of follow-up, y | 14.7 ± 6.0 | 15.4 ± 5.0 | 15.2 ± 4.9 | 14.7 ± 6.0 | |

| Time to first fracture, y | 10.6 ± 5.3 | 11.1 ± 5.4 | 11.6 ± 5.0 | ||

| Any falls | Yes | 7478 (77.3%) | 670 (87.2%) | 553 (86.1%) | 40 (88.9%) |

| Any estrogen use | Yes | 2383 (24.6%) | 182 (23.7%) | 122 (19.0%) | 7 (15.6%) |

| Any raloxifene use | Yes | 86 (0.9%) | 9 (1.2%) | 3 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Any corticosteroid use | Yes | 1019 (10.5%) | 99 (12.9%) | 61 (9.5%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Any bisphosphonate use | Any report | 1136 (11.7%) | 102 (13.3%) | 97 (15.1%) | 9 (20.0%) |

| (excluding etidronate) | 1 report | 860 (8.9%) | 80 (10.4%) | 74 (11.5%) | 7 (15.6%) |

| 2 reports | 236 (2.4%) | 20 (2.6%) | 20 (3.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| 3 or more reports | 40 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Any diabetes | Yes | 1310 (13.5%) | 80 (10.4%) | 82 (12.8%) | 12 (26.7%) |

Of note, most patients in all groups were not current users of bisphosphonates, oral estrogen, or corticosteroids. Current bisphosphonate use was reported for 1136 women (only 11.7% of the study population) at 1 or more of the examinations, including only 9 of the 45 patients who sustained SD fractures. The use of bisphosphonates generally began 10 or more years after the start of the study. Twelve patients with SD fracture were diabetic, and 1 of them was also on bisphosphonates. Only 1 participant with an SD fracture reported taking glucocorticoids.

Among patients who suffered SD fractures, none of them had a bilateral event. Seven of these SD fractures had been preceded by another hip fracture (5 IT, 2 FN), whereas in 3 cases the SD fracture was followed by another hip (IT or FN) IT (n = 2) or FN (n = 1) fracture.

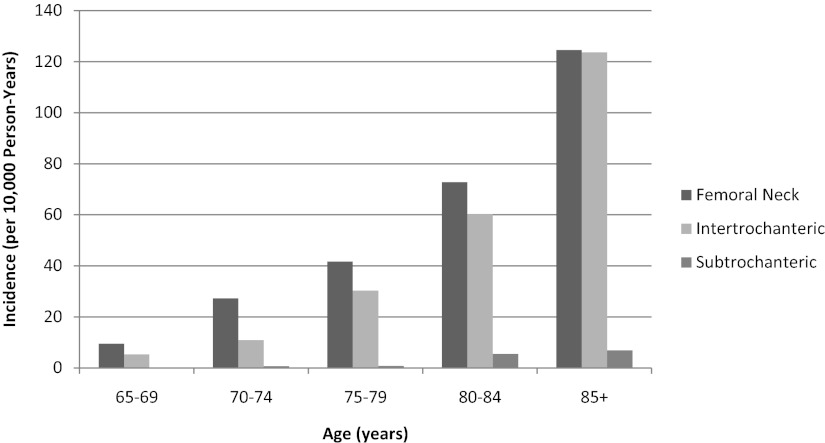

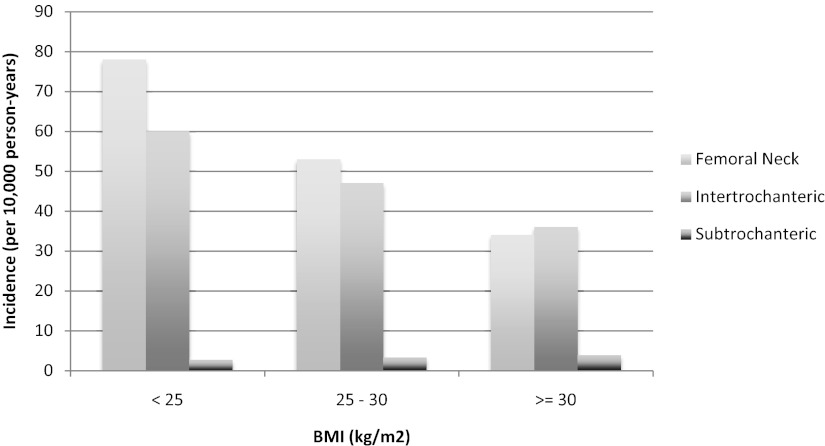

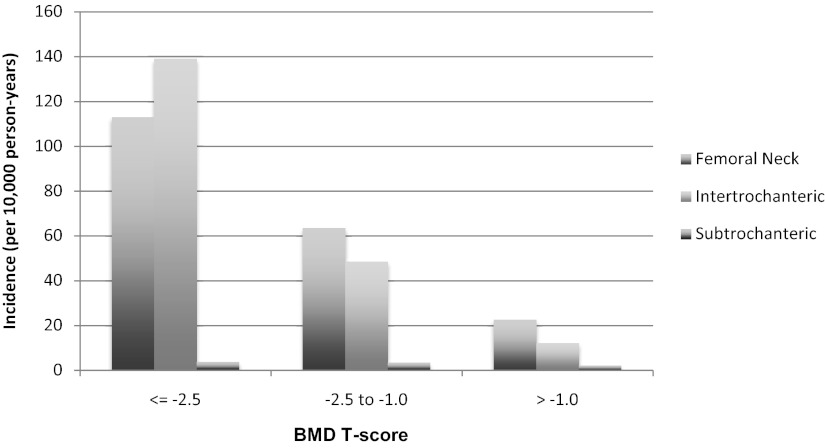

The incidence of SD fractures increased with increasing age, as did that of the other fracture types (Figure 2). The overall incidence of SD fracture was 3.2 per 10 000 person-years compared to rates per 10 000 of 59.7 for FN and 50.2 for IT. Although the incidence of FN and IT fractures decreased with increasing baseline BMI, the incidence of SD fractures increased with an increasing baseline BMI (Figure 3). The incidence rates of all 3 types of fractures increased with decreasing baseline total hip BMD T-score (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Age-specific incidence of hip fractures.

Figure 3.

BMI-specific incidence of hip fractures.

Figure 4.

BMD-specific incidence of hip fractures.

In univariate models, SD fractures increased with age (RH [relative hazard]: 2.04 per 5 years, P < .001) (Table 3). The 2 other significant univariate risk factors for SD fracture were femoral neck BMD (RH/SD decrease: 1.41, P = .04) and diabetes (RH: 2.97, P = .005). There were nonsignificant trends toward increased risk with lower total hip BMD (RH: 1.29 per SD decrease, P = .12), higher BMI (RH: 0.80 per SD decrease, P = .12), a history of falls (RH: 1.75, P = .06), as well as bisphosphonate use (RH: 2.40, P = .06). In the multivariate analysis for SD fracture (Table 4), increased age and diabetes mellitus remained significant (RH: 1.76 per 5 years, P = .0004 and RH: 3.25, P = .002, respectively), whereas lower total hip BMD (RH: 1.53/SD, P = .03) and bisphosphonate use (RH: 2.58, P = .049) became significant as additional independent risk factors.

Table 3.

Relative Hazard of Fracture: Age-Adjusted Univariate Analysis (Time Dependent Covariate Analysis)

| Risk Factor | Unit | Femoral Neck | Intertrochanteric | Subtrochanteric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5 y | 1.56 (1.47, 1.67) | 1.93 (1.80, 2.06) | 2.04 (1.59, 2.63) |

| Total hip BMD | (−) 0.13 g/cm2 | 1.82 (1.67, 1.97) | 2.45 (2.24, 2.67) | 1.29 (0.94, 1.79) |

| BMI | (−) 4.6 kg/m2 | 1.62 (1.49, 1.76) | 1.41 (1.29, 1.54) | 0.80 (0.61, 1.06) |

| Height | (−) 6 cm | 0.89 (0.83, 0.96) | 1.17 (1.08, 1.26) | 1.23 (0.93, 1.64) |

| Exercise (blocks walked per day) | (−) 9.4 blocks | 1.11 (1.01, 1.23) | 1.31 (1.15, 1.49) | 1.32 (0.78, 2.22) |

| History of falls in past year | Yes vs no | 1.38 (1.19, 1.59) | 1.29 (1.10, 1.51) | 1.75 (0.97, 3.16) |

| History of fracture | Yes vs no | 1.62 (1.40, 1.88) | 2.22 (1.88, 2.64) | 1.20 (0.66, 2.20) |

| Prevalent vertebral fracture | Yes vs no | 1.62 (1.39, 1.88) | 2.05 (1.74, 2.40) | 0.88 (0.44, 1.75) |

| Current estrogen use | Yes vs no | 0.85 (0.69, 1.05) | 0.63 (0.48, 0.83) | 0.65 (0.23, 1.82) |

| Current bisphosphonate use | Yes vs no | 0.85 (0.60, 1.19) | 1.17 (0.85, 1.61) | 2.40 (0.97, 5.95) |

| Current glucocorticoid use | Yes vs no | 1.68 (1.22, 2.32) | 1.37 (0.93, 2.01) | 0.69 (0.10, 5.04) |

| Femoral neck BMD | (−) 0.11 g/cm2 | 1.99 (1.83, 2.17) | 2.23 (2.03, 2.45) | 1.41 (1.01, 1.96) |

| History of diabetes | Yes vs no | 0.95 (0.74, 1.22) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.69) | 2.97 (1.47, 6.00) |

Bold indicates a significant value of P < .05.

Table 4.

Relative Hazard of Fracture: Multivariate Analysis

| Risk Factor | Unit | Femoral Neck | Intertrochanteric | Subtrochanteric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5 y | 1.33 (1.23, 1.44) | 1.45 (1.33, 1.57) | 1.76 (1.29, 2.42) |

| Total Hip BMD | (−) 0.13 g/cm2 | 1.64 (1.49, 1.81) | 2.25 (2.03, 2.51) | 1.53 (1.05, 2.24) |

| BMI | (−) 4.6 kg/m2 | 1.32 (1.20, 1.46) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 0.74 (0.53, 1.02) |

| Height | (−) 6 cm | 0.82 (0.76, 0.89) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 1.08 (0.79, 1.47) |

| Exercise (blocks walked per day) | (−) 9.4 blocks | 1.12 (1.00, 1.24) | 1.21 (1.06, 1.39) | 1.10 (0.66, 1.84) |

| History of falls in past year | Yes vs no | 1.40 (1.20, 1.64) | 1.21 (1.02, 1.43) | 1.62 (0.86, 3.04) |

| History of fracture | Yes vs no | 1.33 (1.13, 1.56) | 1.65 (1.36, 1.99) | 1.00 (0.51, 1.94) |

| Prevalent vertebral fracture | Yes vs no | 1.29 (1.09, 1.53) | 1.34 (1.12, 1.60) | 0.65 (0.31, 1.38) |

| Current estrogen use | Yes vs no | 1.00 (0.80, 1.25) | 0.83 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.90 (0.31, 2.59) |

| Current bisphosphonate use | Yes vs no | 0.61 (0.43, 0.87) | 0.76 (0.55, 1.06) | 2.58 (1.01, 6.62) |

| Current glucocorticoid use | Yes vs no | 1.70 (1.22, 2.36) | 1.11 (0.74, 1.66) | 0.69 (0.09, 5.01) |

| History of diabetes | Yes vs no | 1.20 (0.90, 1.58) | 1.76 (1.37, 2.27) | 3.25 (1.55, 6.82) |

Bold indicates a significant value of P < .05.

For FN and IT fractures, multivariate results are also shown in Table 4. For FN fractures, there were a number of significant, independent risk factors including greater age, lower total hip BMD, lower BMI, lower height, history of falls, prevalent vertebral fracture, history of nonvertebral fracture, and exercise level. Associations between several of these significant risk factors, such as exercise and a history of falls, and SD fractures were of similar magnitude and direction but were not statistically significant, perhaps due to the small number of these fractures in this population. Glucocorticoid use was associated with an increased risk of FN fracture. Bisphosphonate use was associated with a 39% decrease in risk, in contrast to the increase in risk observed for SD fractures. For intertrochanteric fractures, age, total hip BMD, exercise level, history of falls, prevalent vertebral fractures, history of nonvertebral fractures, and diabetes were all significant risk factors in the multivariate model. Although there appeared to be a lower risk of IT fractures with bisphosphonate use, the reduction in risk was not significant. There was a small but not significant increase in risk for IT fractures with glucocorticoid use. Of note, diabetes was most strongly associated with SD fractures and was not associated with femoral neck fractures.

Discussion

Our aim was to use the SOF cohort to determine the incidence of and risk factors for low-energy subtrochanteric and diaphyseal fractures in comparison with more traditional femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures in a population of older community-dwelling, primarily bisphosphonate-naïve women with long-term follow-up. SOF is a unique resource for these aims because it is a prospective study that includes risk factor information obtained prior to the fractures themselves and was performed during a period when bisphosphonate use was low. We found that SD fractures were related to greater age and a history of diabetes mellitus. Hip BMD, strongly associated with other types of hip fractures, was also found to be a risk factor for these fractures after an adjustment for other risk factors. We also confirmed in this analysis that femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures were related to known risk factors such as greater age, lower hip BMD, lower BMI, less exercise, history of falls, history of fractures, and glucocorticoid use.

In the SOF cohort, we examined the incidence of SD fractures and found they were very rare, with an overall incidence of about 3.2 per 10 000 person-years compared with FN and IT fractures (59.7 per 10 000 and 50.2 per 10 000, respectively). In our study, SD fractures represented about 5% of all fractures of the femur, similar to the 5%–10% seen in a number of other studies (13, 17, 22), which classified SD fractures in a variety of ways.

Because the great majority of follow-up in our study occurred prior to the introduction of bisphosphonates or among women who had not taken bisphosphonates, this allows us to estimate the background incidence of SD fractures in untreated women and to examine risk factors unaffected by bisphosphonates. Several previous studies have examined incidence of SD fractures prior to the introduction of bisphosphonates (6–11) using a variety of study designs. Although the methods for defining fractures of the femoral shaft have varied among the studies [eg, evaluation of individual radiographs (6–8) vs International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (9), differing trauma definitions and morphologic regions, etc], these studies all showed exponential increases with increasing age in women after 65 years, particularly among those over 80 years, as we also found.

Ours is the first study to have risk factors, including hip BMD values, collected prior to the SD fractures. We have shown that low BMD is a risk factor for SD fractures, even if the association is weaker than for other hip fractures. This may indicate that other risk factors may play a relatively larger role in the development of SD fractures. In addition, it is possible that total hip BMD does not accurately reflect the density or strength in the femoral shaft because the shaft is below the DXA region of interest.

The relationship of bisphosphonate use to SD fractures is of high current interest, but the SOF has significant limitations, and is not the ideal data set to address this question. In fact, the limited number of patients on treatment and the lack of precise information on cumulative dose of bisphosphonates limit our ability to assess the relationship to SD fracture risk. Despite these limitations, SOF is unique in this area in having prospectively assessed confounders, including BMD, and can therefore adjust for confounding by indication. After adjustment, we found that there was an approximate doubling in the risk of SD fractures among bisphosphonate users compared with nonfractured controls, which was marginally significant (P = .049). The value of covariate adjustment can be seen in our results for FN fracture, which showed no statistically significant risk reduction for bisphosphonate use in age-adjusted models (15%, P = .34) but after adjustment for additional factors including BMD increased to a statistically significant risk reduction of 39% (P = .006), similar to that shown in randomized trials of bisphosphonates (23, 24). In SOF, the magnitude of the relative hazard of bisphosphonate use for SD fractures (RH: 2.58) was modest and consistent with some studies (16, 17, 22) but less than that shown by others (15, 25). Other studies have not shown a significant increase in risk of SD fracture with bisphosphonate use (13, 14). Given the very low incidence of SD fractures, our data are consistent with other analyses that have shown that the benefits of bisphosphonates in osteoporotic women strongly outweigh these risks (14). There is a need for larger observational studies, with the ability to prospectively adjust for confounding, to further address this question.

Our data confirmed that there was a strong association between glucocorticoid use and FN fractures. On the other hand, there were too few users of glucocorticoids to allow us to assess whether glucocorticoids increased the risk of SD fractures as has been suggested by some (13) but not all other studies (15, 17). Unlike the trend toward an increased risk for bisphosphonate use and SD fractures, estrogen users showed a trend toward a reduced risk of SD fractures.

One particularly interesting finding in our data was that comorbid diabetes mellitus was associated with both SD and intertrochanteric fractures. In cross-sectional epidemiological studies, diabetes has previously been associated with a 34%–100% higher risk of hip fractures (26–28). For a given BMD T-score, patients with diabetes have a higher risk of hip fracture compared with those without diabetes (29). We confirmed this result in our study and showed that IT, but not FN, hip fractures were increased in those with diabetes after BMD adjustment. There are few data about the relationship of diabetes to SD fracture. Recently a retrospective case-cohort study found a higher rate of prevalent diabetes among patients who sustained SD fractures compared with other types of hip fractures (22% in patients with SD fractures compared with 7% in hip fracture controls) (30). We found a 3.25 times increased risk (P = .002) of SD fractures in those with diabetes after adjustment for BMD and other risk factors. It is noteworthy that 12 patients with SD fracture were diabetic and only 1 of them was on bisphosphonates, indicating a clear effect of the disease on the onset of these fractures independently of bisphosphonate use. It has been proposed that patients with diabetes may have impaired bone quality, and, although several mechanisms have been proposed, the pathophysiology is still unclear. Recent peripheral high-resolution computed tomography studies have found that patients with diabetes have both denser trabecular bone and a 124% higher intracortical porosity compared with controls in the distal radius and tibia, leading to an estimated 2.5%–3.0% decrease in biomechanical properties (31, 32). Histomorphometry data obtained in animal models indicate that diabetes causes a low bone turnover condition with impaired bone formation and mineral apposition rate (33, 34). This histological pattern is in part similar to that reported in patients on long-term treatment with bisphosphonates who sustain SD fractures (3, 35).

The methods and criteria for defining subtrochanteric fractures have varied substantially between studies, and therefore, comparison of incidence between studies is problematic. We used radiographic reports, whereas most other epidemiological studies have used ICD codes (12, 13, 17) or more recently have evaluated radiographs (15, 16, 25). The information in the reports allowed us to exclude the fractures extending proximally into the intertrochanteric region as well as periprosthetic, pathological, and high-energy fractures, none of which can be defined with ICD codes alone. However, having only the radiographic reports, compared with the radiographs, is an important limitation because we could not confirm the morphological characteristics or evaluate atypical features. Compared with previous studies, another potential point of interest of our findings is that none of the patients that we reported suffered of a bilateral SD fracture and few of them had a multiple hip fracture. This is consistent with previous studies of SD fractures that showed a low proportion of bilateral fractures in bisphosphonate-naïve women (6–8) compared with a larger proportion in case reports of atypical femur fracture (1, 5). This may suggest a different pathophysiology of SD fractures in those patients who are mostly bisphosphonates naïve.

The lack of availability of radiographs to directly evaluate fracture morphology is a limitation of our study. Another limitation is the small number of SD fractures that occurred, which limits the power to identify risk factors and to establish a link between bisphosphonate use and these fractures. This low number of detected fractures among more than 9000 participants over more than 140 000 patient-years of follow-up highlights the very low incidence of these fractures and the difficulty in studying them prospectively. Another limitation is that the study was limited to white women in the United States aged 65 years old and older and therefore may not apply to other groups. Lastly, our method of assessment of bisphosphonate use does not allow us to reliably assess the duration of use or the relationship of duration to fracture risk.

In conclusion, our prospective study showed that the absolute incidence of SD fractures was very low compared with the total incidence of hip fractures. Among traditional hip fracture risk factors, only age and hip BMD were associated with SD fractures. Interestingly, diabetes was also a strong independent risk factor for SD and IT fractures. Subject to the limitations of our study design, these results provide some support for an association of SD fractures with bisphosphonate use that could not be explained by confounders available in this study. Further study of the interaction of these risk factors with bisphosphonates on the pathophysiology of SD fractures is needed.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Lucy Wu (University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California) for editorial assistance on the manuscript. L.P. and D.M.B. accept responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis. The authors' roles in this work include the following: D.M.B., J.C., and K.E. were responsible for the study design; L.P., R.W., A.C., J.C., K.E., M.K., and D.M.B. were responsible for the study conduct; D.M.B., R.W., M.K., A.C., J.C., and K.E. were responsible for the data collection; L.P., D.M.B., and J.J. were responsible for the data analysis; N.N., J.J., L.P., J.C., K.E., and D.M.B. were responsible for the data interpretation; N.N., J.J., L.P., R.W., and D.M.B. were responsible for the drafting of the manuscript and revising the contents; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The SOF study is supported by Grants AG05407, AR35582, AG05394, AR35584, AR35583, AR46238, AG005407, AG08415, AG027576-22, AG005394-22A1, AG027574-22A1, and AG030474 from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and National Institute on Aging).

Disclosure Summary: N.N. has a consulting agreement with Merck, Sharp, and Dohme. A.V.S. has grant support from Merck. L.P. has consulting fees Nycomed. J.A.C. has consulting fees from the Horizon Steering Committee (Novartis) and Merck, and grant support from Novartis. D.M.B. has research contracts with Novartis, Merck, and Roche and consulting fees with Eli Lilly, Nycomed, and Amgen. K.E.E. has served as a consultant on a Data Monitoring Committee for Merck, Sharpe, and Dohme. J.J., R.W., and M.K. have no disclosures.

Footnotes

- BMD

- Bone mineral density

- BMI

- body mass index

- DXA

- dual x-ray absorptiometry

- FN

- femoral neck

- ICD

- International Classification of Diseases

- IT

- intertrochanteric region

- RH

- relative hazard

- SD

- subtrochanteric and diaphyseal

- SOF

- Study of Osteoporotic Fractures.

References

- 1. Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2267–2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Odvina CV, Levy S, Rao S, Zerwekh JE, Sudhaker Rao D. Unusual mid-shaft fractures during long term bisphosphonate therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2009;72(2):161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armamento-Villareal R, Napoli N, Diemer K, et al. Bone turnover in bone biopsies of patients with low-energy cortical fractures receiving bisphosphonates: a case series. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;85:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lenart BA, Lorich DG, Lane JM. Atypical fractures of the femoral diaphysis in postmenopausal women taking alendronate. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1304–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures of the femur and bisphosphonate therapy. A systematic review of case/case series studies. Bone. 2010;47:169–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salminen S, Pihlajamaki H, Avikainen V, Kyro A, Bostman O. Specific features associated with femoral shaft fractures caused by low-energy trauma. J Trauma. 1997;43:117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salminen ST, Pihlajamaki HK, Avikainen VJ, Bostman OM. Population based epidemiologic and morphologic study of femoral shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arneson TJ, Melton LJ, Lewallen DG, O'Fallon WM. Epidemiology of diaphyseal and distal femoral fractures in Rochester, MN, 1965–1984. Clin Orthop. 1988;234:188–194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hedlund R, Lindgren U. Epidemiology of diaphyseal femoral fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57:423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bengner U, Ekbom T, Johnell O, Nilsson BE. Incidence of femoral and tibial shaft fractures. Epidemiology 1950–1983 in Malmo, Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knowelden J, Buhr AJ, Dunbar O. Incidence of fractures in persons over 35 years of age. A report to the M.R.C. working party on fractures in the elderly. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1964;18:130–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nieves JW, Bilezikian JP, Lane JM, et al. Fragility fractures of the hip and femur: incidence and patient characteristics. Osteoporos Int. 2009;21(3):399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: a register-based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1095–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, et al. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1761–1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feldstein AC, Black DM, Perrin N, et al. Incidence and demography of femur fractures with and without atypical features. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5):977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rizzoli R, Akesson K, Bouxsein M, et al. Subtrochanteric fractures after long-term treatment with bisphosphonates: a European Society on Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, and International Osteoporosis Foundation Working Group Report. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:373–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:767–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet. 1993;341:72–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cauley JA, Lui LY, Genant HK, et al. Risk factors for severity and type of the hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:943–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Cumulative alendronate dose and the long-term absolute risk of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures: a register-based national cohort analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5258–5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dell RM, Adams AL, Greene DF, et al. Incidence of atypical nontraumatic diaphyseal fractures of the femur. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(12):2544–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Janghorbani M, Van Dam RM, Willett WC, Hu FB. Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koh JS, Goh SK, Png MA, Kwek EB, Howe TS. Femoral cortical stress lesions in long-term bisphosphonate therapy: a herald of impending fracture? J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barbour KE, Zmuda JM, Horwitz MJ, et al. The association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D with indicators of bone quality in men of Caucasian and African ancestry. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2475–2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Bauer DC, et al. Association of BMD and FRAX score with risk of fracture in older adults with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2011;305:2184–2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Dekkers OM, Ramautar SR, Dijkstra S, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures and bisphosphonate therapy: a cohort study of patients with femoral fracture with radiographic adjudication of fracture site and features. Bone. 2011;48:966–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burghardt AJ, Issever AS, Schwartz AV, et al. High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomographic imaging of cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5045–5055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petit M, Paudel ML, Taylor B, et al. Bone mass and strength in older men with type 2 diabetes: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:285–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hamada Y, Kitazawa S, Kitazawa R, Fujii H, Kasuga M, Fukagawa M. Histomorphometric analysis of diabetic osteopenia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice: a possible role of oxidative stress. Bone. 2007;40:1408–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fujii H, Hamada Y, Fukagawa M. Bone formation in spontaneously diabetic Torii-newly established model of non-obese type 2 diabetes rats. Bone. 2008;42:372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Armamento-Villareal R, Napoli N, Panwar V, Novack D. Suppressed bone turnover during alendronate therapy for high-turnover osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2048–2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]