Abstract

Papaver rhoeas, an annual plant species in the Papaveraceae family, is part of the biodiversity of agricultural ecosystems and also a noxious agronomic weed. We developed microsatellite markers to study the genetic diversity of P. rhoeas, using an enriched microsatellite library coupled with 454 next-generation sequencing. A total of 13,825 sequences were obtained that yielded 1795 microsatellite loci. After discarding loci with less than six repeats of the microsatellite motif, automated primer design was successful for 598 loci. We tested 74 of these loci for amplification with a total of 97 primer pairs. Thirty loci passed our tests and were subsequently tested for polymorphism using 384 P. rhoeas plants originating from 12 populations from France. Of the 30 loci, 11 showed reliable polymorphism not affected by the presence of null alleles. The number of alleles and the expected heterozygosity ranged from 3 to 7.4 and from 0.27 to 0.73, respectively. A low but significant genetic differentiation among populations was observed (FST = 0.04; p < 0.001). The 11 validated polymorphic microsatellite markers developed in this work will be useful in studies of genetic diversity and population structure of P. rhoeas, assisting in designing management strategies for the control or the conservation of this species.

Keywords: Papaver rhoeas, Papaveraceae, microsatellite markers, next-generation sequencing, genetic diversity

1. Introduction

The Papaver genus in the Papaveraceae family comprises 100 species distributed in various countries around the world, from central and south Europe to temperate Asia, America, Oceania and South Africa [1]. Papaver rhoeas L. (corn poppy) is one of the most well-known members of this genus, easily identified by its scarlet flowers. This species has been the symbol for Remembrance Day (or Poppy Day) since the end of WWI, which makes it a heritage species. P. rhoeas is a semelparous species that thrives in disturbed land. It has a high reproductive potential through its seeds, which are dormant and have long viability, thus facilitating its persistence and spread [2–4]. Its abundant pollen is an important food source for honeybees during their foraging period [5] as well as for other beneficial insects [6,7]. On the other hand, P. rhoeas can dominate agricultural fields, where it is listed as a serious annual weed of winter cereal crops that can cause significant yield losses because of its high competitive ability [8]. The agronomic significance of P. rhoeas also includes indirect harmful effects on crops through the harbouring of phytopathogenic viruses [9].Various uses have been documented for all plant parts of P. rhoeas [10].

P. rhoeas is an insect-pollinated, diploid hermaphroditic species (2n = 14) with high self-incompatibility [11]. Outcrossing contributes to high levels of genetic variation and heterozygosity [12]. P. rhoeas has been reported to exhibit high phenotypic plasticity and high genetic variation, which for example results in variable petal pigmentation and leaf shape [13].

Quantification of genetic diversity within and among populations of P. rhoeas is important for the study of the ecology and population structure of this species. Such studies can assist in implementing management strategies in the context of either conservation ecology or weed control. Simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers, also called microsatellite markers, are popular tools used to assess the genetic diversity of species [14]. Their advantages include good repeatability, a high level of polymorphism and co-dominance. There are currently no microsatellite markers available for genetic comparisons between P. rhoeas populations. The aim of this work was to develop and validate polymorphic microsatellite markers for P. rhoeas, and to assess the genetic variation in 12 P. rhoeas populations from France.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Next-Generation Sequencing Results

A total of 13,825 sequences were obtained from the P. rhoeas enriched library. Average sequence length was 240 nucleotides, with a maximum length of 570 nucleotides. After discarding short sequences (less than 80 nucleotides) and sequences without microsatellite motifs, the remaining sequences were filtered for redundancy and multiple copies in the sequence data set. In total, 1795 validated microsatellite loci were identified. Automated primer design was successful for 829 loci. Loci with less than six repeats of the microsatellite motif were discarded, yielding 598 loci for which the QDD pipe-line generated 4453 primer pairs.

2.2. Development of Microsatellite Markers

We selected 74 of the 598 microsatellite loci based on the lowest value of the “penalty” index computed by QDD. A total of 97 primer pairs were tested to amplify the 74 loci. An amplicon was consistently obtained from 30 of the 74 selected loci. The 30 amplicons were sequenced in both directions with the corresponding primer pair. They were all confirmed to contain the expected microsatellite motif, and polymorphism was observed for all loci among the seven P. rhoeas plants used for screening. Among the 30 loci, 20 carried a dinucleotide motif and 10 a trinucleotide motif. The remaining 44 loci were not further considered because no amplicon could be obtained, or amplicons were not obtained for all seven P. rhoeas plants used for screening, or no polymorphism was detected after sequencing the amplicons.

The 30 microsatellite loci were further tested on 384 P. rhoeas plants (12 populations of 32 individuals each). The software MicroChecker [15] was used to identify microsatellites with null alleles or large allele drop-out (i.e., short allele dominance due to PCR artefacts). There was no evidence for large allele drop-out in any loci. Null alleles can cause deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and can introduce substantial bias in population genetic analyses. Loci for which null alleles were detected in a majority of populations (more than seven populations among the 12 studied) were, therefore, not further considered. This screening resulted in a final set of 11 microsatellite loci, the characteristics of which are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

The set of 11 microsatellite markers developed in P. rhoeas. F, forward, and R, reverse primer sequences, Ta, annealing temperature.

| Locus | Repeat motif | Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Ta (°C) | Size range (bp) | GenBank accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMS002 | TC | F: TTCACAACCTAAGTTCCCCTG | 60 | 107–139 | HF547289 |

| R: ACAAATCGAAACCCCTAATTTG | 60 | ||||

| PMS005 | CT | F: CCCCAATCAAAGAAGCTTGATG | 60 | 170–183 | HF547290 |

| R: GATATGATATGTCCCTCTCAATGG | 60 | ||||

| PMS006 | GA | F: GAATTCCATTCCCACTCAATATC | 60 | 241–255 | HF547291 |

| R: CAGCAGCAGCATTTATCCTCAAC | 60 | ||||

| PMS015 | AC | F: ATCCCCTGTTGATCCAATTG | 60 | 203–222 | HF547292 |

| R: TTGCGATGTTTATAGGGCAC | 60 | ||||

| PMS037 | TCT | F: ACTGATACTACTTCTTCCTCCACC | 60 | 78–193 | HF547293 |

| R: TCGAAGAGCCTGTATTTGAATC | 60 | ||||

| PMS039 | TC | F: TTGATCTGCTCTTACAAACCC | 60 | 105–123 | HF547294 |

| R: CCAGAAAAGTAGAATATTGATTGAGTTG | 60 | ||||

| PMS051 | GAA | F: GGAATCTCGTGGCATTCATTTAC | 60 | 201–241 | HF547295 |

| R: GAATCTTCTCCAAACACATCGAAC | 60 | ||||

| PMS052 | AG | F: TAGCTGTACGGAAGAGCAAGC | 60 | 168–249 | HF547296 |

| R: CGATCTCTTCCCGTGTCC | 60 | ||||

| PMS054 | CA | F: GACTTAAACTCGGCAACATCAC | 60 | 51–153 | HF547297 |

| R: ATATGGTTGTGAATGAGTTAGCTTG | 60 | ||||

| PMS061 | TG | F: GATGTGCGTCTACGAGATTTGG | 60 | 211–221 | HF547298 |

| R: ACCGATTACCAGAAACAGATCG | 60 | ||||

| PMS073 | TTC | F: TCTTCTGCATAAGGAGCATGAG | 60 | 127–145 | HF547299 |

| R: TGATGATATCTTGGAAGAATTGG | 60 |

2.3. Genotyping and Population Genetics Analysis

A total of 384 plants from 12 natural populations of P. rhoeas collected in cultivated fields in France (32 plants per population) were genotyped at the 11 microsatellite loci. The average number of alleles per population (NA) was between 3.0 (locus PMS073) and 7.4 (locus PMS002). The mean expected heterozygosity per population (HE) also varied widely among loci, ranging from 0.271 (locus PMS073) to 0.731 (locus PMS037). Significant pairwise linkage disequilibrium was detected for only three pairs of loci: PMS005 and PMS073 (p-value < 0.01), PMS015 and PMS073 (p-value < 0.001) and PMS039 and PMS054 (p-value < 0.001).

A slight deficit in heterozygotes was observed for most loci in most populations, as indicated by positive FIS values (Table 2). Locus PMS002 showed a significant deficit in heterozygotes in seven populations among the 12 studied. Microchecker analyses detected null alleles at this locus in these populations. This is likely the cause of the observed deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. We therefore recommend this locus should be used with caution. Excluding locus PMS002 from the analyses did not alter the values of expected heterozygosity (HE) observed over all loci in each population. Four other loci (PMS015, PMS051, PMS052 and PMS061) also showed some deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. However, for each locus, this was only observed in one or two populations among the 12 studied (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the initial primer screening on 32 individuals from 12 populations of P. rhoeas.

| Locus | BE | CF | CY | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Na | HO | HE | FIS | Na | HO | HE | FIS | Na | HO | HE | FIS | |

| PMS002 | 9 | 0.548 | 0.808 | 0.321 * | 6 | 0.625 | 0.723 | 0.136 | 10 | 0.366 | 0.607 | 0.396 * |

| PMS005 | 6 | 0.594 | 0.700 | 0.152 | 6 | 0.687 | 0.690 | 0.003 | 9 | 0.687 | 0.769 | 0.106 |

| PMS006 | 5 | 0.562 | 0.641 | 0.122 | 5 | 0.719 | 0.775 | 0.073 | 5 | 0.742 | 0.709 | −0.046 |

| PMS015 | 7 | 0.437 | 0.485 | 0.098 | 4 | 0.500 | 0.592 | 0.156 | 7 | 0.406 | 0.719 | 0.435 * |

| PMS037 | 6 | 0.687 | 0.730 | 0.058 | 4 | 0.594 | 0.671 | 0.116 | 9 | 0.656 | 0.813 | 0.193 |

| PMS039 | 6 | 0.750 | 0.776 | 0.034 | 5 | 0.594 | 0.739 | 0.196 | 7 | 0.594 | 0.688 | 0.136 |

| PMS051 | 4 | 0.312 | 0.332 | 0.058 | 3 | 0.156 | 0.148 | −0.054 | 6 | 0.344 | 0.308 | −0.116 |

| PMS052 | 4 | 0.129 | 0.336 | 0.616 * | 5 | 0.125 | 0.179 | 0.303 | 8 | 0.531 | 0.616 | 0.138 |

| PMS054 | 5 | 0.531 | 0.568 | 0.065 | 6 | 0.625 | 0.583 | −0.072 | 5 | 0.500 | 0.406 | −0.232 |

| PMS061 | 4 | 0.344 | 0.327 | −0.052 | 4 | 0.406 | 0.442 | 0.080 | 2 | 0.344 | 0.425 | 0.192 |

| PMS073 | 3 | 0.156 | 0.149 | −0.047 | 3 | 0.500 | 0.411 | −0.216 | 4 | 0.500 | 0.415 | −0.205 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Locus | CS | DN | FE | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| NA | HO | HE | FIS | NA | HO | HE | FIS | NA | HO | HE | FIS | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PMS002 | 4 | 0.166 | 0.217 | 0.231 | 6 | 0.333 | 0.763 | 0.563 * | 7 | 0.387 | 0.419 | 0.076 |

| PMS005 | 5 | 0.625 | 0.662 | 0.056 | 4 | 0.687 | 0.638 | −0.078 | 5 | 0.677 | 0.688 | 0.016 |

| PMS006 | 5 | 0.562 | 0.709 | 0.207 | 5 | 0.625 | 0.698 | 0.105 | 6 | 0.656 | 0.661 | 0.007 |

| PMS015 | 5 | 0.656 | 0.722 | 0.091 | 5 | 0.437 | 0.452 | 0.032 | 3 | 0.594 | 0.513 | −0.158 |

| PMS037 | 8 | 0.750 | 0.758 | 0.010 | 5 | 0.594 | 0.741 | 0.199 | 6 | 0.719 | 0.692 | −0.039 |

| PMS039 | 7 | 0.774 | 0.817 | 0.053 | 6 | 0.625 | 0.638 | 0.021 | 5 | 0.719 | 0.716 | −0.004 |

| PMS051 | 5 | 0.562 | 0.461 | −0.220 | 8 | 0.344 | 0.436 | 0.212 | 6 | 0.313 | 0.404 | 0.227 |

| PMS052 | 4 | 0.500 | 0.405 | −0.235 | 6 | 0.281 | 0.335 | 0.161 | 5 | 0.290 | 0.338 | 0.140 |

| PMS054 | 7 | 0.719 | 0.605 | −0.187 | 6 | 0.625 | 0.656 | 0.048 | 3 | 0.581 | 0.475 | −0.223 |

| PMS061 | 4 | 0.375 | 0.424 | 0.116 | 3 | 0.531 | 0.458 | −0.161 | 4 | 0.500 | 0.513 | 0.026 |

| PMS073 | 3 | 0.344 | 0.297 | −0.156 | 3 | 0.313 | 0.280 | −0.117 | 3 | 0.313 | 0.279 | −0.119 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Locus | IS | MA | MI | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| NA | HO | HE | FIS | NA | HO | HE | FIS | NA | HO | HE | FIS | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PMS002 | 7 | 0.500 | 0.793 | 0.369 * | 7 | 0.400 | 0.623 | 0.358 * | 9 | 0.516 | 0.719 | 0.283 * |

| PMS005 | 6 | 0.844 | 0.751 | −0.124 | 5 | 0.500 | 0.679 | 0.264 | 5 | 0.600 | 0.484 | −0.240 |

| PMS006 | 5 | 0.594 | 0.728 | 0.184 | 5 | 0.625 | 0.658 | 0.050 | 5 | 0.594 | 0.718 | 0.173 |

| PMS015 | 6 | 0.406 | 0.425 | 0.045 | 5 | 0.500 | 0.624 | 0.199 | 5 | 0.531 | 0.584 | 0.091 |

| PMS037 | 5 | 0.594 | 0.690 | 0.139 | 6 | 0.781 | 0.741 | −0.054 | 5 | 0.531 | 0.652 | 0.185 |

| PMS039 | 6 | 0.906 | 0.788 | −0.150 | 6 | 0.656 | 0.616 | −0.065 | 5 | 0.719 | 0.696 | −0.033 |

| PMS051 | 5 | 0.156 | 0.207 | 0.246 | 6 | 0.250 | 0.475 | 0.474 * | 7 | 0.438 | 0.490 | 0.108 |

| PMS052 | 5 | 0.625 | 0.561 | −0.114 | 4 | 0.219 | 0.303 | 0.279 | 6 | 0.226 | 0.267 | 0.153 |

| PMS054 | 4 | 0.406 | 0.505 | 0.196 | 6 | 0.531 | 0.592 | 0.103 | 4 | 0.281 | 0.426 | 0.340 |

| PMS061 | 4 | 0.188 | 0.329 | 0.430 * | 3 | 0.219 | 0.352 | 0.378 | 4 | 0.484 | 0.455 | −0.064 |

| PMS073 | 2 | 0.156 | 0.146 | −0.069 | 3 | 0.406 | 0.343 | −0.185 | 3 | 0.344 | 0.303 | −0.133 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Locus | PY | ST | TY | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| NA | HO | HE | FIS | NA | HO | HE | FIS | NA | HO | HE | FIS | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PMS002 | 9 | 0.433 | 0.559 | 0.225 | 8 | 0.467 | 0.764 | 0.389 * | 7 | 0.531 | 0.665 | 0.201 |

| PMS005 | 5 | 0.563 | 0.715 | 0.213 | 5 | 0.656 | 0.600 | −0.094 | 5 | 0.375 | 0.526 | 0.287 |

| PMS006 | 6 | 0.719 | 0.729 | 0.014 | 4 | 0.656 | 0.649 | −0.012 | 4 | 0.839 | 0.682 | −0.229 |

| PMS015 | 7 | 0.688 | 0.662 | −0.038 | 6 | 0.469 | 0.429 | −0.092 | 5 | 0.531 | 0.592 | 0.103 |

| PMS037 | 9 | 0.750 | 0.771 | 0.027 | 7 | 0.719 | 0.804 | 0.106 | 5 | 0.688 | 0.713 | 0.079 |

| PMS039 | 6 | 0.656 | 0.780 | 0.158 | 6 | 0.719 | 0.718 | −0.001 | 7 | 0.656 | 0.688 | 0.045 |

| PMS051 | 4 | 0.281 | 0.257 | −0.096 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.348 | 0.641 * | 7 | 0.469 | 0.504 | 0.069 |

| PMS052 | 5 | 0.344 | 0.458 | 0.249 | 5 | 0.387 | 0.477 | 0.188 | 8 | 0.469 | 0.447 | −0.050 |

| PMS054 | 7 | 0.613 | 0.562 | −0.091 | 6 | 0.531 | 0.643 | 0.174 | 6 | 0.563 | 0.621 | 0.095 |

| PMS061 | 4 | 0.400 | 0.542 | 0.262 | 3 | 0.469 | 0.487 | 0.037 | 6 | 0.290 | 0.341 | 0.150 |

| PMS073 | 3 | 0.219 | 0.203 | −0.080 | 3 | 0.281 | 0.252 | −0.116 | 3 | 0.188 | 0.176 | −0.063 |

NA: number of alleles, HO: observed heterozygosity, HE: expected heterozygosity, FIS: inbreding coefficient. (*) indicates significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p-value < 0.01).

Considering all loci except PMS002, the mean FIS value within population varied between −0.005 and 0.14. Under the assumption that deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was due solely to inbreeding, the rate of autogamy, calculated as s = 2 FIS/(1+ FIS), varied between 0% and 24% (overall mean: 11%). For several samples, the estimated rates of autogamy seemed to conflict with the self-incompatible mating system described in P. rhoeas [11]. We suspect that deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in these samples resulted either from biparental inbreeding (i.e., mating among relatives due to limited seed dispersal and restricted pollinator flight distances), or from population subdivision at the level of each sampled field (Walhund effect). This remains to be investigated.

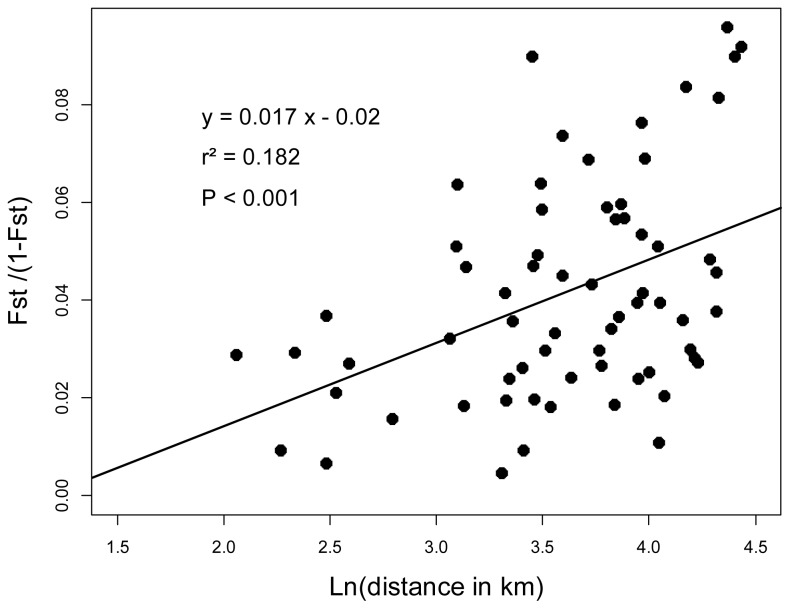

When considering all 11 loci, the expected genetic diversity within population was always high, ranging from 0.518 to 0.589 (overall mean: 0.547). The genetic differentiation among all populations, as measured by FST, was 0.04. This indicated large population sizes and/or high gene flow, as expected in an allogamous plant species [12]. Although low, the genetic differentiation among populations was highly significant (p-value < 0.001). Pairwise FST values computed for all possible pairs of populations ranged from 0.009 to 0.087. A significant linear relationship was observed between pairwise FST/(1 − FST) values and the natural logarithm of geographical distances between populations (r2 = 0.182; p < 0.001) (Figure 1). This indicates isolation-by-distance among populations [16].

Figure 1.

Plot of genetic distances versus geographic distances for all possible pairs of the sampled populations.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Material

Twelve P. rhoeas populations were sampled in agricultural fields in the Burgundy region (France) during the summer of 2011 (Table 3). Samples consisted of one green leaf collected from each of 32 plants per field. The plants sampled were distributed across the field.

Table 3.

Geographic origins of the 12 P. rhoeas populations used in this study.

| Code | Population | Latitude (N) | Longtitude (E) | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE | Beaunotte | 47.678028 | 4.681338 | 302 |

| CF | Chamboeuf | 47.234224 | 4.890333 | 471 |

| CY | Chevigny | 47.181531 | 5.475732 | 215 |

| CS | Chivres | 46.977046 | 5.102653 | 175 |

| DN | Détain | 47.155948 | 4.782923 | 585 |

| FE | Fénay | 47.233031 | 5.065271 | 221 |

| IS | Isômes | 47.643463 | 5.284272 | 277 |

| MA | Marliens | 47.218520 | 5.190730 | 196 |

| MI | Mirande | 47.302668 | 5.080832 | 245 |

| PY | Perrigny | 47.287745 | 5.453528 | 190 |

| ST | St Thibault | 47.368827 | 4.472117 | 356 |

| TY | Talmay | 47.380004 | 5.462555 | 217 |

3.2. Microsatellite Library and Primer Design

The approach used has been described elsewhere [17]. Briefly, a microsatellite-enriched library was generated using a high-throughput method based on the coupling of multiplex microsatellite enrichment and next-generation sequencing on a 454 GS-FLX Titanium platform. The sequences generated were analysed using the QDD pipe-line [18], following the procedure described in [17]. Primer pairs were designed automatically using the Primer3 algorithm [19] implemented in the QDD pipeline with the setup described in [17].

3.3. Loci Selection and Primer Editing

Microsatellite loci of interest were selected among those identified by running the QDD pipe-line using the following criteria: (1) a target microsatellite sequence containing at least six repeats of the microsatellite motif, and (2) an expected amplicon of 90 to 350 bp in length. Editing of the primer sequences generated by QDD was performed when necessary to ensure an annealing temperature around 60 °C, and the presence of a C or G nucleotide at each primer 3′ end to increase the stability of primer binding to its target. The edited primers were then checked for self-complementarity and complementarity between primers in a same pair to avoid the formation of primer dimers. Primers sequences were further edited as needed.

3.4. DNA Amplification and Genotyping

All primer pairs were tested for PCR amplification on DNA extracted from seven P. rhoeas plants originating from five populations: FE (3 plants), BE (1 plant), ST (1 plant), CS (1 plant) and PY (1 plant). Geographic origins of the populations are shown in Table 3. DNA was extracted using a rapid method [20]. PCR amplifications were performed using a Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) thermocycler, in a 20 μL reaction mix containing 70 mM Tris-HCL, 2 mM MgCl2, 17 mM (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% (wt/vol) polyoxyethylene-ether W1, 0.2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 200 mM of each dNTP, 10 ng genomic DNA, 0.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.2 μM each of reverse and forward primers. The PCR program used consisted of 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 37 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C, 10 s at 60 °C and 30 s at 72 °C [21]. Amplicons were visualised under UV light by electrophoresis on a 3% (wt/vol) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. When an intense amplicon was obtained from all seven plants, it was sequenced in both directions by Sanger sequencing to confirm the presence of the expected microsatellite motif. Primer pairs yielding amplicons in which the presence of the expected microsatellite motif was confirmed and polymorphism was observed by sequencing were used to genotype the corresponding microsatellite locus in the 12 P. rhoeas populations of 32 individuals each (Table 3).

The DNA extracts of all plants were diluted 50-fold prior to genotyping with fluorescent labelled markers. PCR products were dye-labelled (6-FAM, NED, VIC or PET directly attached to the forward primer in each primer pair) and assayed on an ABI 3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using 500 liz (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as a size standard. Amplicon sizes were analyzed with GeneMapper 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

3.5. Data Analysis

Micro-Checker v2.2.3 [15] was used to detect genotyping errors due to null alleles, stuttering, or allele dropout. The FSTAT software [22] was used to estimate standard genetic diversity parameters: the number of alleles per locus (NA), observed (HO) and expected (HE) levels of heterozygosity as well as the inbreeding coefficient FIS were estimated for each population. Genetic differentiation among populations was estimated using Weir and Cockerham’s FST [23]. Deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) at each locus within each sample were tested in FSTAT using 5000 random permutations of alleles among individuals. Because of multiple testing within each sample, we used a nominal significance level of 0.01. Significance of the genetic differentiation among populations as measured by FST was tested, based on 5000 random permutations of genotypes among populations.

4. Conclusions

The 11 polymorphic microsatellites developed for P. rhoeas proved reliable for population genetic studies. Based on a sample of populations clustered within roughly 150 km, we observed a level of genetic differentiation that was low but that increased significantly with geographical distances. This suggests that addressing population structure in P. rhoeas at a geographical scale larger than the scale considered here should reveal more genetic polymorphism and higher levels of genetic differentiation. On the other hand, fine-scale studies are necessary to elucidate the existence of some genetic structure within cultivated fields. Future studies, based on the 11 polymorphic microsatellites we developed, will enable a better understanding of the patterns of genetic diversity of P. rhoeas, providing information on population structure and dynamics that can be useful for guiding management strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the EU project BPI-PlantHeal 230010 (FP7-REGPOT-2008-1-01). The authors are very grateful to Dr. T. Malausa (INRA, UMR1301 IBSV, Sophia-Antipolis, France) for running the QDD pipe-line.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Holm L., Doll J., Holm E., Pancho J.V., Herberger J.P. World Weeds: Natural Histories and Distribution. John Wiley and Sons Inc; New York, NY, USA: 1997. p. 1129. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutman P.J.W., Cussans G.W., Wright K.J., Wilson B.J., Lawson H.M. The persistence of seeds of 16 weed species over six years in two arable fields. Weed Res. 2002;42:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirujeda A., Recasens J., Taberner A. Dormancy cycle and viability of buried seeds of Papaver rhoeas. Weed Res. 2006;46:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cirujeda A., Aibar J., Zaragoza C. Remarkable changes of weed species in Spanish cereal fields from 1976 to 2007. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011;31:675–688. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimou M., Thrasyvoulou A. Seasonal variation in vegetation and pollen collected by honeybees in Thessaloniki, Greece. Grana. 2007;46:292–299. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Free J.B., Gennard D., Stevenson J.H., Williams I.H. Beneficial insects present on a motorway verge. Biol. Conserv. 1975;8:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgio G., Lanzoni A., Navone P., van Achterberg K., Masetti A. Parasitic Hymenoptera fauna on Agromyzidae (Diptera) colonizing weeds in ecological compensation areas in Northern Italian agroecosystems. J. Econ. Entomol. 2007;100:298–306. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493(2007)100[298:phfoad]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torra J., Recasens J. Demography of corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas) in relation to emergence time and crop competition. Weed Sci. 2008;56:826–833. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens M., Smith H.G., Hallsworth P.B. The host range of beet yellowing viruses among common arable weed species. Plant Pathol. 1994;43:579–588. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duke J. Utilization of Papaver. Econ. Bot. 1973;27:390–400. [Google Scholar]

- 11.East E.M. The distribution of self-sterility in the flowering plants. P. Am. Philos. Soc. 1940;82:449–518. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamrick J.L., Godt M.J.W. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B. 1996;351:1291–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNaughton I.H., Harper J.L. Biological flora of the British Isles. Papaver L. J. Ecol. 1964;52:767–793. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell W., Machray G.C., Provar J. Polymorphism revealed by simple sequence repeats. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Oosterhout C., Hutchinson W.F., Wills D.P.M., Shipley P. Micro-Checker: Software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2004;4:535–538. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rousset F. Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation-by-distance. Genetics. 1997;145:1219–1228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malausa T., Gilles A., Meglécz E., Blanquart H., Duthoy S., Costedoat C., Dubut V., Pech N., Castagnone-Sereno P., Délye C., et al. High-throughput microsatellite isolation through 454 GS-FLX Titanium pyrosequencing of enriched DNA libraries. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011;11:638–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.02992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meglécz E., Costedoat C., Dubut V., Gilles A., Malausa T., Pech N., Martin J.F. QDD: A user-friendly program to select microsatellite markers and design primers from large sequencing projects. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:403–404. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozen S., Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for General Users and for Biologist Programmers. In: Krawetz S., Misener S., editors. Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ, USA: 2000. pp. 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Délye C., Boucansaud K., Pernin F., Le Corre V. Variation in the gene encoding acetolactate-synthase in Lolium species and proactive detection of mutant, herbicide-resistant alleles. Weed Res. 2009;49:326–336. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caullet C.M.L., Pernin F., Poncet C., Le Corre V. Development of microsatellite markers in Capsella rubella and Capsella bursa-pastoris (Brassicaceae) Am. J. Bot. 2011;98:176–179. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goudet J. FSTAT (Version 1.2): A computer program to calculate F-statistics. J. Hered. 1995;86:485–486. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockerham C.C., Weir B.S. Estimation of gene flow from F-statistics. Evolution. 1993;47:855–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]