Abstract

The influences of eight metal ions (i.e., Na+, Ca2+, Ag+, Co2+, Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Mn4+) on mycelia growth and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production in liquid culture of the endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 were investigated. Three metal ions, Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ were exhibited as the most effective to enhance mycelia growth and palmarumycin production. When calcium ion (Ca2+) was applied to the medium at 10.0 mmol/L on day 3, copper ion (Cu2+) to the medium at 1.0 mmol/L on day 3, aluminum ion (Al3+) to the medium at 2.0 mmol/L on day 6, the maximal yields of palmarumycins C12 plus C13 were obtained as 137.57 mg/L, 146.28 mg/L and 156.77 mg/L, which were 3.94-fold, 4.19-fold and 4.49-fold in comparison with that (34.91 mg/L) of the control, respectively. Al3+ favored palmarumycin C12 production when its concentration was higher than 4 mmol/L. Ca2+ had an improving effect on mycelia growth of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. The combination effects of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ on palmarumycin C13 production were further studied by employing a statistical method based on the central composite design (CCD) and response surface methodology (RSM). By solving the quadratic regression equation between palmarumycin C13 and three metal ions, the optimal concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ in medium for palmarumycin C13 production were determined as 7.58, 1.36 and 2.05 mmol/L, respectively. Under the optimum conditions, the predicted maximum palmarumycin C13 yield reached 208.49 mg/L. By optimizing the combination of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ in medium, palmarumycin C13 yield was increased to 203.85 mg/L, which was 6.00-fold in comparison with that (33.98 mg/L) in the original basal medium. The results indicate that appropriate metal ions (i.e., Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+) could enhance palmarumycin production. Application of the metal ions should be an effective strategy for palmarumycin production in liquid culture of the endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12.

Keywords: endophytic fungus, Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12, spirobisnaphthalene, palmarumycin C12, palmarumycin C13, metal ions, calcium ion, copper ion, aluminum ion, center composite design, response surface methodology

1. Introduction

Plant endophytic fungi colonize interior organs of plants without causing apparent symptoms of pathogenesis [1]. They are responsible for the adaptation of plants to abiotic stresses such as drought, cold, light and metals, as well as to biotic ones such as herbivores, insects and pathogens [2]. Endophytic fungi act as a reservoir of genetic diversity, and have been proven to be a rich source of biologically active natural products [3–6]. They have also been found to produce the same or similar important metabolites produced by the host plants, such as alkaloids, steroids, phenolics, terpenoids and peptides [7].

Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 is an endophytic fungus derived from the rhizomes of Dioscorea zingiberensis C. H. Wright (Dioscoreaceae), a well-known traditional Chinese medicinal herb indigenous to the south of China [8,9]. In our previous studies, six spirobisnaphthalenes were obtained from Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12, and both palmarumycins C12 and C13 were found to be the predominant components [8,10]. Palmarumycin C12 showed antifungal activity on Ustilago violacea and Eurotium repens [11]. Palmarumycin C13 (also variously named Sch 53514, diepoxin ζ and cladospirone bisepoxide) exhibited obvious antibacterial and antifungal [8,12], antitumor activity, and inhibitory activity on phospholipase D (PLD) [13]. Spirobisnaphthalenes are a rapidly growing group of naphthoquinone derivatives with the interesting structures and various biological activities such as antitumor, antibacterial, antifungal, antileishmanial, enzyme-inhibitory, and other properties to display their potential applications in agriculture, medicine and the food industry [14,15]. These tremendous discoveries about spirobisnaphthalenes attracted the attention of many researchers.

In order to speed up application of palmarumycins C12 and C13, one of the most important approaches is to increase yields of palmarumycins C12 and C13 in fermentation culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. Various strategies have been developed to increase metabolite yield in microorganism or plant cultures, which include optimization of medium, utilization of two-phase culture systems, addition of precursors and metal ions, as well as application of elicitation by using polysaccharides and oligosaccharides [16–24]. Many metal ions (i.e., K+, Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Co2+, Ni+, Cu2+, Zn2+ and Mo+) are essential for microorganisms. They can interact with microbial cells and may play important functions in cell growth and metabolism [25,26]. The mycelia pellet formation and fumaric acid production were significantly affected by the trace metal ions Mg2+, Zn2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+ in fermentation culture of Rhizopus oryzae ATCC 20344 [27]. Mycelia growth and polysaccharide production were obviously enhanced by the metal ions Zn2+, Se2+ and Fe2+ in submerged culture of Ganoderma lucidum [28].

In our previous studies, obvious enhancement of palmarumycins C12 and C13 production in the liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 was achieved by using yeast extract and its fractions [29], in situ resin adsorption [30], polysaccharides, and oligosaccharides from the host plant Dioscorea zingiberensis [10,31]. Spirobisnapthalenes belong to polyketide metabolites produced by some fungi [14]. Biosynthetically, they are generated by the 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) pathway which contains a series of biochemical reactions including oxidation and reduction [32,33]. In this study, we deal with eight metal ions in medium affecting production of palmarumycins C12 and C13 in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. Firstly, the single metal ion at its different concentrations was added in medium to screen its enhancing effect. Secondly, three effective metal ions (Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+) along with their addition time were studied to obtain the appropriate combination of addition time and concentration for each ion. Lastly, the combination effects of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ on palmarumycin C13 production in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 were studied by employing statistical method based on the central composite design (CCD) and response surface methodology (RSM) to realize the maximization of palmarumycin C13 yield. To the best of our knowledge, the effects of metal ions on palmarumycin production of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 have not yet been reported. The purpose was to investigate the enhancing effects of the metal ions for palmarumycins C12 and C13 biosynthesis in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12, as well as to provide data supporting palmarumycin production on a large scale.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effects of Metal Ions on Mycelia Growth and Palmarumycin Production

Eight metal ions (i.e., Na+, Ca2+, Ag+, Co2+, Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Mn4+) were added in medium on day 3 of culture. The effects of the metal ions on mycelia growth and palmarumycin production in Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 liquid culture are presented in Table 1. Three metal ions, Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ showed improving effects on the mycelia growth and palmarumycin accumulation. The optimum concentrations to stimulate mycelia growth for Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ were respectively at 20.00, 3.00 and 3.00 mmol/L. However, the optimal concentrations to obviously increase total palmarumycin yield (palmarumycins C12 plus C13) for Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ were respectively at 10.00, 1.50 and 3.00 mmol/L. Correspondingly, total palmarumycin yields at the optimal concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ were respectively at 129.24, 112.26 and 112.82 mg/L, which were 4.00-fold, 3.47-fold, and 3.49-fold of control yield (32.32 mg/L), respectively. Zinc ions (Zn2+) slightly stimulated mycelia growth, and had no obvious effect on total palmarumycin production. Among the other metal ions (i.e., Na+, Ag+, Co2+ and Mn4+), both Ag+ and Co2+ strongly inhibited mycelia growth, and both Na+ and Mn4+ slightly inhibited mycelia growth. Correspondingly, total palmarumycin yield of endophyte Dzf12 liquid cultures was decreased after treatment with the metal ions Na+, Ag+, Co2+ and Mn4+, respectively. The inhibitory capacity of the metal ions for palmarumycins C12 and C13 production in Dzf12 liquid culture was in order of Co2+ > Ag+ > Mn4+ > Na+. It was concluded that both Co2+ and Ag+ exhibited the most toxic to Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 by inhibiting mycelia growth and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production. Three metal ions, Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ were the most effective at enhancing mycelia growth and palmarumycin production. They were selected for further enhancing experiments for palmarumycin production.

Table 1.

Effects of eight metal ions on mycelia growth and palmarumycin production in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. Each metal ion was added in medium on day 3 of culture. The period of culture lasted for 13 days. Palmarumycins C12 and C13 are abbreviated as C12 and C13, respectively.

| Metal ion | Conc. (mmol/L) | Mycelia biomass (g dw/L) | C12 yield (mg/L) | C13 yield (mg/L) | C12 plus C13 yield (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 0.00 | 6.79 ± 0.08 cde | 1.29 ± 0.03 fgh | 31.03 ± 0.06 h | 32.32 ± 0.13 g |

|

| |||||

| Na+ | 5.00 | 5.81 ± 0.18 fg | 0.66 ± 0.01 ghi | 16.10 ± 0.21 ij | 16.76 ± 0.32 ij |

| 10.00 | 5.83 ± 0.13 fg | 3.00 ± 0.17 e | 19.25 ± 0.34 i | 22.25 ± 1.51 hi | |

| 20.00 | 5.96 ± 0.25 efg | 2.06 ± 0.19 e | 19.39 ± 0.15 i | 21.45 ± 0.38 hi | |

|

| |||||

| Ca2+ | 5.00 | 7.26 ± 0.17 bcd | 4.98 ± 0.21 d | 91.57 ± 1.76 d | 96.55 ± 2.66 c |

| 10.00 | 7.32 ± 0.44 bcd | 14.76 ± 0.31 a | 114.48 ± 6.76 a | 129.24 ± 7.12 a | |

| 20.00 | 7.58 ± 0.10 bc | 13.79 ± 0.90 a | 83.48 ± 2.37 e | 97.27 ± 3.63 c | |

|

| |||||

| Ag+ | 0.05 | 3.21 ± 0.29 k | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 0.67 ± 0.13 | l 0.67 ± 0.13 k |

| 0.10 | 3.17 ± 0.26 k | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 0.44 ± 0.16 l | 0.44 ± 0.16 k | |

| 0.50 | 2.99 ± 0.31 k | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 0.32 ± 0.09 l | 0.32 ± 0.09 k | |

|

| |||||

| Co2+ | 0.05 | 4.35 ± 0.50 ij | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 0.30 ± 0.02 l | 0.30 ± 0.02 k |

| 0.10 | 4.29 ± 0.18 ij | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 0.39 ± 0.09 l | 0.39 ± 0.09 k | |

| 0.50 | 3.52 ± 0.76 jk | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 0.21 ± 0.10 l | 0.21 ± 0.10 k | |

|

| |||||

| Cu2+ | 0.50 | 7.51 ± 0.33 b | 1.42 ± 0.18 fg | 78.97 ± 0.26 e | 80.39 ± 4.13 d |

| 1.50 | 7.67 ± 0.22 b | 6.65 ± 0.06 c | 105.61 ± 1.70 b | 112.26 ± 3.07 b | |

| 3.00 | 7.82 ± 0.13 b | 4.62 ± 0.21d | 63.84 ± 0.86 f | 68.46 ± 1.06 e | |

|

| |||||

| Al3+ | 0.50 | 7.08 ± 0.33 bcd | 2.20 ± 0.86 ef | 51.49 ± 2.16 g | 53.69 ± 4.77 f |

| 1.50 | 8.09 ± 0.29 ab | 8.38 ± 0.85 b | 97.83 ± 3.67 cd | 106.21 ± 5.50 bc | |

| 3.00 | 8.82 ± 0.33 a | 9.00 ± 0.62 d | 103.82 ± 5.80 bc | 112.82 ± 9.41 b | |

|

| |||||

| Zn2+ | 2.00 | 7.09 ± 0.27 bcd | 0.32 ± 0.15 ghi | 15.85 ± 1.97 ij | 16.17 ± 1.57 ij |

| 4.00 | 7.66 ± 0.18 bc | 0.63 ± 0.13 ghi | 31.42 ± 2.54 h | 32.05 ± 1.63 g | |

| 8.00 | 6.49 ± 0.39 def | 0.59 ± 0.14 ghi | 29.67 ± 1.58 h | 30.26 ± 2.01 gh | |

|

| |||||

| Mn4+ | 2.00 | 4.79 ± 0.28 hi | 0.14 ± 0.01 hi | 7.23 ± 0.42 kl | 7.37 ± 0.77 jk |

| 4.00 | 5.43 ± 0.51 gh | 0.15 ± 0.02 hi | 7.43 ± 0.81 kl | 7.58 ± 0.52 jk | |

| 8.00 | 5.82 ± 0.49 fg | 0.20 ± 0.00 hi | 10.10 ± 0.19 kj | 10.30 ± 1.01 jk | |

Note: CK, a control without addition of the test metal ions; C12, palmarumycin C12; C13, palmarumycin C13; the values are expressed as means ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among the treatments in each column including different metal ions and their concentrations at p = 0.05 level.

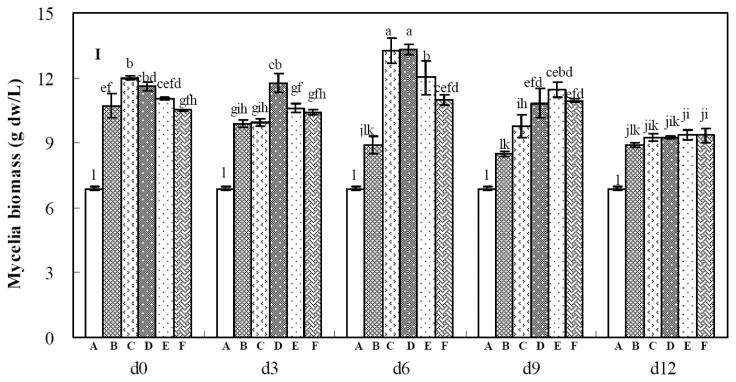

2.2. Effects of Calcium Ion Addition Time on Mycelia Growth and Palmarumycin Production

Addition time of the metal ions has been considered as a main factor to affect biosynthesis of fungal or plant secondary metabolites [16,18]. Calcium ion (Ca2+) was found to be one of the most effective ions to improve mycelia growth and palmarumycin biosynthesis in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12, based on the results shown in Table 1. Hence, Ca2+ concentrations in medium and addition time were further optimized. As the three-day-old cultures treated with 10 mmol/L of Ca2+ reached an ideal palmarumycin production (129.24 mg/L), the highest concentration of Ca2+ in subsequent studies was limited at 20 mmol/L. Figure 1 shows the effects of Ca2+ on mycelia growth (Figure 1-I) and palmarumycin yield (Figure 1-II) in Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 liquid cultures, which were dependent on both Ca2+ concentrations (1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 mmol/L) and its addition time (added on days 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12). As shown in Figure 1-I, when the cultures were fed with 10 mmol/L of Ca2+ on day 6, the mycelia biomass was 1.94-fold of control (13.32 g dw/L versus 6.88 g dw/L). Palmarumycin C13 was distributed in both mycelia and broth, and palmarumycin C12 was only distributed in mycelia. With 10 mmol/L of Ca2+ fed on day 3, the highest yields of palmarumycins C12 (23.65 mg/L) and C13 (113.92 mg/L) were obtained. The total palmarumycin yield (palmarumycins C12 plus C13) was improved to reach 137.57 mg/L, which was about 3.94-fold of control yield (34.91 mg/L) (Figure 1-II).

Figure 1.

Effects of calcium ion (Ca2+) and its addition time on mycelia growth (I) and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production (II) in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. The period of culture lasted for 13 days. The error bars represent standard deviations from three independent samples. Different letters indicate significant differences among the treatments at p = 0.05 level. Palmarumycins C12 and C13 are abbreviated as C12 and C13, respectively. A, B, C, D, E and F denote 0, 1, 5, 10, 15 and 20 mmol/L of Ca2+ concentration in medium, respectively.

Calcium ion (Ca2+) plays an essential role in signal transduction as it is one component of the calcium ion channel. Calcium signaling can result in rapid cellular responses, such as cell motility and contractile events, or more slowly paced responses, such as shifts in gene expression and cell division [34]. Ca2+ was reported to obviously accelerate the growth of the fungus Sesarma bidens [35]. It was also reported to cause thickening of the fungal cell walls of Botrytis cinerea [36]. Ca2+ uptake is localized in the apex of the tip of fungal hyphae, and Ca2+ has been considered to have an important role on fungal tip growth [37–39]. Ca2+ was also found to stimulate mycelia growth of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 in this study. Its action mechanisms to improve mycelia growth and palmarumycin biosynthesis need further investigation.

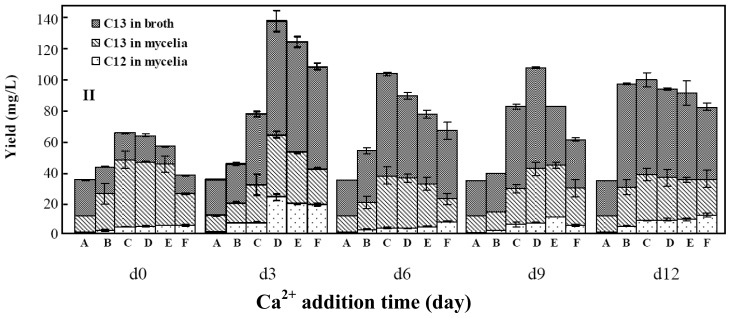

2.3. Effects of Copper Ion Addition Time on Mycelia Growth and Palmarumycin Production

Copper ion (Cu2+) was also found to be one of the most effective ions to improve mycelia growth and palmarumycin biosynthesis in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 based on the results shown in Table 1. Therefore, Cu2+ concentration and addition time were further optimized. As the three-day-old cultures treated with 1.50 mmol/L of Cu2+ reached an ideal palmarumycin production (112.26 mg/L), the highest concentration of Cu2+ in subsequent studies was limited at 3.00 mmol/L. Figure 2 shows the effects of Cu2+ on mycelia growth (Figure 2-I) and palmarumycin yield (Figure 2-II) in Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 liquid cultures, which were dependent on both Cu2+ concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 3.0 mmol/L) and its addition time (added on days 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12). As shown in Figure 2-I, when the cultures were fed with 0.5–3.0 mmol/L of Cu2+ on days 0–12, the mycelia biomass was varied as 6.49–7.84 g dw/L which was higher than that of control (6.88 g dw/L). With 1.0 mmol/L of Cu2+ fed on day 3, the highest yields of palmarumycins C12 (6.37 mg/L) and C13 (139.91 mg/L) were obtained. The total palmarumycin yield (palmarumycins C12 plus C13) was improved to reach 146.28 mg/L, which was about 4.19-fold of control yield (34.91 mg/L) (Figure 2-II). Cu2+ was previously reported to improve the production of laccase by the white-rot fungus Pleurotus pulmonarius in solid state fermentation [40].

Figure 2.

Effects of copper ion (Cu2+) and its addition time on mycelia growth (I) and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production (II) in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. The period of culture lasted for 13 days. The error bars represent standard deviations from three independent samples. Different letters indicate significant differences among the treatments at p = 0.05 level. Palmarumycins C12 and C13 are abbreviated as C12 and C13, respectively. A, B, C, D, E and F denote 0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 3.0 mmol/L of Cu2+ concentration in medium, respectively.

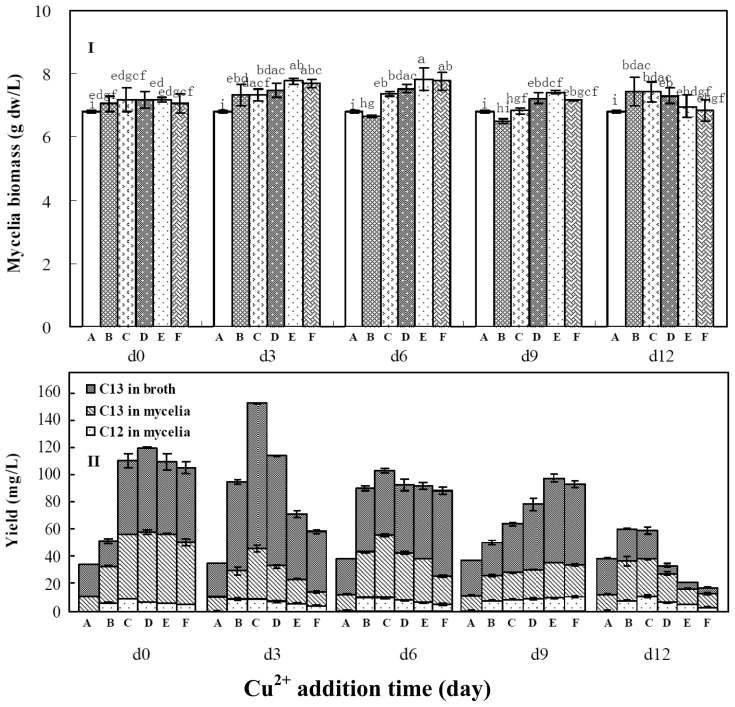

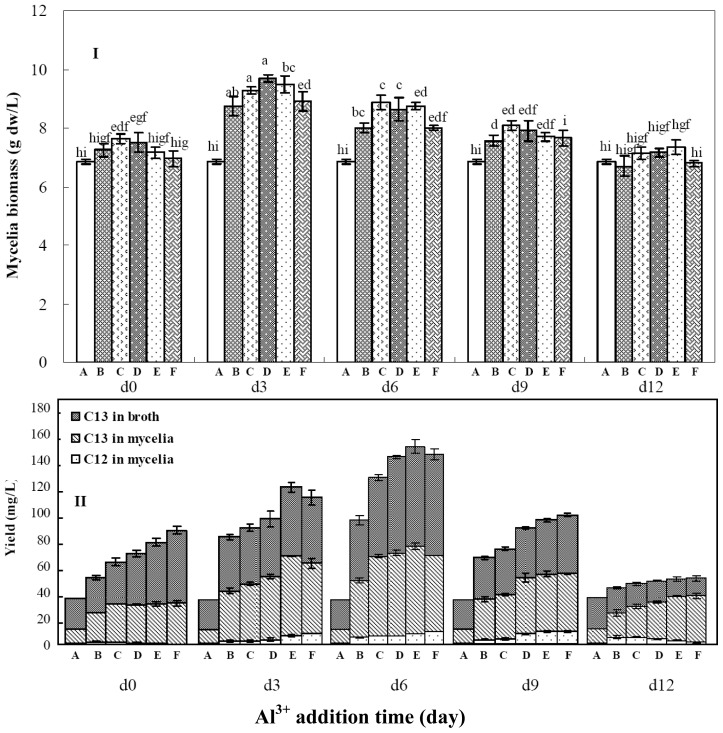

2.4. Effects of Aluminum Ion Addition Time on Mycelia Growth and Palmarymycin Production

Effects of aluminum ion (Al3+) on mycelia growth and palmarumycin production in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 are shown in Figure 3. As the three-day-old cultures treated with 1.50 mmol/L of Al3+ reached an ideal palmarumycin production (106.21 mg/L), the highest concentration of Al3+ in subsequent studies was limited at 2.50 mmol/L. Figure 3 shows the effects of Cu2+ on mycelia growth (Figure 3-I) and palmarumycin yield (Figure 3-II) in Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 liquid cultures, which were dependent on both Al3+ concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 mmol/L) and its addition time (added on days 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12). As shown in Figure 3-I, when the cultures were fed with 1.5 mmol/L of Al3+ on day 3, the mycelia biomass was 9.69 g dw/L which was higher than that of control (6.88 g dw/L). With 2.0 mmol/L of Al3+ fed on day 6, the highest yields of palmarumycins C12 (8.28 mg/L) and C13 (148.49 mg/L) were obtained. The total palmarumycin yield (palmarumycins C12 plus C13) was improved to reach 156.77 mg/L, which was about 4.49-fold of control yield (34.91 mg/L) (Figure 3-II).

Figure 3.

Effects of aluminum ion (Al3+) and its addition time on mycelia growth (I) and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production (II) in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. The period of culture lasted for 13 days. The error bars represent standard deviations from three independent samples. Different letters indicate significant differences among the treatments at p = 0.05 level. Palmarumycins C12 and C13 are abbreviated as C12 and C13, respectively. A, B, C, D, E and F denote 0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 mmol/L of Al3+ concentration in medium, respectively.

Palmarumycin C13 production was mainly enhanced when Al3+ concentration was lower than 4 mmol/L (Table 2 and Figure 3). When Al3+ concentration was higher than 4 mmol/L, palmarumycin C12 production was favored. The ratio of palmarumycin C12 yield to palmarumycin C13 yield was gradually increased (Table 2). Biosynthetically, palmarumycin C12 was considered as the precursor of palmarumycin C13 [32,33]. Palmarumycin C12 was converted to palmarumycin C13 by oxidation reaction in mycelia cells. It is possible that the enzyme activity for oxidation was suppressed as the aluminum ion concentration was higher than 4 mmol/L. While aluminum ion concentration was higher than 8 mmol/L, the total yield of palmarumyicns C12 plus C13 gradually decreased. It is possible that high Al3+ concentration leads to the suppression of other enzymatic activities in the biosynthetic pathway of palmarumycins besides the oxidation enzyme. The results should be beneficial for us to prepare palmarumycin C12 or palmarumycin C13 by regulating activity of the oxidation enzyme with aluminum ions. Al3+ at a high concentration is usually toxic to plants, animals and microorganisms [35]. For example, Al3+ completely inhibited the growth of the fungus Sesarma bidens at 100 mg/L AlCl3 in medium [41]. However, it possesses a variety of biological activities at low concentrations [42]. Al3+ enhanced the conversion of (β-isoxazolin-5-on-2-yl)-alanine (BIA) into β-N-oxalyl-L-α,β-diaminopropionic acid (β-ODAP) in the callus tissues derived from leaf explants of Lathyrus sativus [43]. Production of some plant secondary metabolites can be elicited by Al3+. For example, resveratrol biosynthesis in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) was stimulated by Al3+ at a concentration of 0.05% AlCl3 in medium [44]. Tropane alkaloid production and antioxidant system activity in micropropagated Datura innoxia plantlets were enhanced by Al3+ as an abiotic elicitor [45]. It has not yet been reported how aluminum ions suppress the enzyme-based oxidation. Aluminum ions directly joining the biotransformation step from palmarumycin C12 to palmarumycin C13 needs further clarification.

Table 2.

Effects of aluminum ion on mycelia growth and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. Aluminum ion was added in medium on day 3 of culture. The period of culture lasted for 13 days. Palmarumycins C12 and C13 are abbreviated as C12 and C13, respectively.

| Aluminum ion conc. (mmol/L) | Mycelia biomass (g dw/L) | C12 yield (mg/L) | C13 yield (mg/L) | C12 plus C13 yield (mg/L) | Ratio of C12 yield to C13 yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7.35 ± 0.17 d | 1.83 ± 0.48 c | 38.14 ± 3.21 d | 39.97 ± 3.07 d | 0.05 |

| 2 | 11.16 ± 0.24 abc | 9.98 ± 1.47 c | 117.26 ± 5.70 b | 127.24 ± 4.25 c | 0.09 |

| 4 | 11.85 ± 0.41 ab | 14.94 ± 1.25 c | 166.27 ± 3.42 a | 181.21 ± 2.87 b | 0.09 |

| 6 | 11.76 ± 1.21 ab | 106.59 ± 5.31 b | 162.93 ± 4.08 a | 269.52 ± 5.19 a | 0.65 |

| 8 | 13.17 ± 0.39 a | 224.33 ±10.08 a | 59.23 ± 2.72 c | 283.56 ± 8.08 a | 3.79 |

| 10 | 10.51 ± 1.01 bc | 118.85 ± 3.93 b | 4.19 ± 0.93 e | 123.04 ± 3.91 c | 28.36 |

| 12 | 9.49 ± 0.98 cd | 115.55 ± 2.97 b | 3.58 ± 0.13 e | 119.13 ± 2.88 c | 32.28 |

Note: C12, palmarumycin C12; C13, palmarumycin C13; the values are expressed as means ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among the treatments in each column at p = 0.05 level.

2.5. Combination Effects of Calcium, Copper and Aluminum Ions on Palmarumycin C13 Production

According to the above single-factor experiments, Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ all showed their obvious effects on palmarumycin C13 production in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12, and palmarumycin C13 yield was in the majority of palmarumycins C12 plus C13 yield (Figures 1-II, 2-II and 3-II). So the suitable concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ in medium for palmarumycin C13 production were further determined by central composite design (CCD) experiments and response surface methodology (RSM). Five levels of each variable were set by the software of Design Expert, which are presented in Table 3. Subsequently, 20 trials of CCD were carried out to optimize palmarumycin C13 yield. The results of CCD experiments were summarized in Table 4. Palmarumycin C13 yield displayed considerable variations from 163.22 to 209.64 mg/L, respectively, depending upon the changes of variables. Based on the results of CCD experiments, a second-order polynomial regression model between palmarumycin C13 yield and the test independent variables by software of Design Expert was shown in Equation 1.

Table 3.

Coded values (x) and uncoded values (X) of variables in the central composite design (CCD) experiments.

| Variable (mmol/L) | Symbol | Coded level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Uncoded | Coded | −1.682 | −1 | 0 | 1 | +1.682 | |

| Ca2+ | X1 | x1 | 1.59 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 18.41 |

| Cu2+ | X2 | x2 | 0.65 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.34 |

| Al3+ | X3 | x3 | 1.16 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.84 |

Table 4.

CCD experimental matrix and the response values for the experiments.

| Run | x1 | x2 | x3 | Palmarumycin C13 yield (mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Experimental Ye | Predicted Yp | Ye − Yp | ||||

| 1 | 1.68 | 0 | 0 | 163.22 | 161.47 | 1.75 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | −1.68 | 177.98 | 179.53 | −1.55 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 202.40 | 206.31 | −3.91 |

| 4 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 189.29 | 190.14 | −0.85 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 206.74 | 206.31 | 0.43 |

| 6 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 166.33 | 167.58 | −1.25 |

| 7 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 182.75 | 181.70 | 1.05 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 209.64 | 206.31 | 3.33 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 179.77 | 181.50 | −1.73 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 205.98 | 206.31 | −0.33 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 207.10 | 206.31 | 0.79 |

| 12 | 0 | 1.68 | 0 | 194.98 | 193.70 | 1.28 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 1.68 | 186.67 | 184.83 | 1.84 |

| 14 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 170.37 | 169.72 | 0.65 |

| 15 | −1.68 | 0 | 0 | 189.26 | 190.72 | −1.46 |

| 16 | 0 | −1.68 | 0 | 192.91 | 193.90 | −0.99 |

| 17 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 197.38 | 195.86 | 1.52 |

| 18 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 198.36 | 197.78 | 0.58 |

| 19 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 176.34 | 177.12 | −0.78 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 205.94 | 206.31 | −0.37 |

| (1) |

In Equation 1,Y represented palmarumycin C13 yield (mg/L), and x1, x2 and x3 were the coded values of the test variables, the concentrations (mmol/L) of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+, respectively.

In order to determine whether the quadratic regression model was significant or not, the ANOVA analysis was conducted, which was summarized in Table 5. The ANOVA of the quadratic regression model demonstrated that the model was highly significant, evident from Fisher’s test with a very high model F-value (84.65) but a very low p-value (p < 0.0001). The goodness of the model was examined by the determination coefficients (R2) and multiple correlation coefficients (R). For palmarumycin C13 yield, the value (0.9754) of the determination coefficient adj-R2 demonstrated that total variation of 97.54% was attributed to the test independent variables and only about 2.46% of the total variation could not be explained by the model. The value of R was closer to 1, the fitness of the model was better [46]. In this study, the multiple correlation coefficient (adj-R) of the model was 0.9876, indicating a good agreement between the experimental and predicted values. The lack-of-fit measured the failure of the model to represent the data in the experimental domain at points which were not included in the regression [47]. The F-value for lack-of-fit was 0.86 and the corresponding p-value was 0.56 (> 0.05), which implied each lack-of-fit was not significant relative to the pure error due to noise. Insignificant lack-of-fit confirmed the validity of the model.

Table 5.

Palmarumycin C13 yield analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the fitted quadratic polynomial model.

| Source | Sum of squares | d.f. | Mean square | F value | Probability p > | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 3890.94 | 9 | 432.33 | 84.65 | <0.0001 | |

| Residual | 51.08 | 10 | 5.12 | |||

| Lack of fit | 23.61 | 5 | 4.72 | 0.86 | 0.56 | |

| Pure error | 27.46 | 5 | 5.49 | |||

| Corrected total | 3942.02 | 19 |

R2 = 0.9870; adj-R2 = 0.9754; R = 0.9935; adj-R = 0.9876; CV (%) = 1.19.

The coefficients of the quadratic polynomial model, along with their corresponding p-values, are calculated and presented in Table 6. The p-value was used as a tool to check the significance of each coefficient, which also indicated the interaction strength between each independent parameter [48]. If the p-value was smaller, the significance of the corresponding coefficient should be bigger. It can be seen from Table 6 that most of regression coefficients of the quadratic polynomial models were significant with low p-values.

Table 6.

Regression coefficient and their significance test of the quadratic polynomial model for palmarumycin C13 yield.

| Model Term | Coefficient estimate | Standard error | Sum of Squares | d.f. | Mean square | F value | Probability p > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 206.31 | 0.92 | |||||

| x1 | −8.70 | 0.61 | 1032.61 | 1 | 1032.61 | 202.17 | <0.0001 |

| x2 | −0.060 | 0.61 | 0.049 | 1 | 0.049 | 0.0095 | 0.9243 |

| x3 | 1.58 | 0.61 | 33.92 | 1 | 33.92 | 6.64 | 0.0275 |

| x1x2 | 5.39 | 0.80 | 232.41 | 1 | 232.41 | 45.50 | <0.0001 |

| x1x3 | −1.017 | 0.80 | 8.27 | 1 | 8.27 | 1.62 | 0.2320 |

| x2x3 | 1.63 | 0.80 | 21.23 | 1 | 21.23 | 4.16 | 0.0688 |

| x12 | −10.68 | 0.60 | 1644.34 | 1 | 1644.34 | 321.94 | <0.0001 |

| x22 | −4.42 | 0.60 | 281.79 | 1 | 281.79 | 55.17 | <0.0001 |

| x32 | −8.53 | 0.60 | 1048.77 | 1 | 1048.77 | 205.34 | <0.0001 |

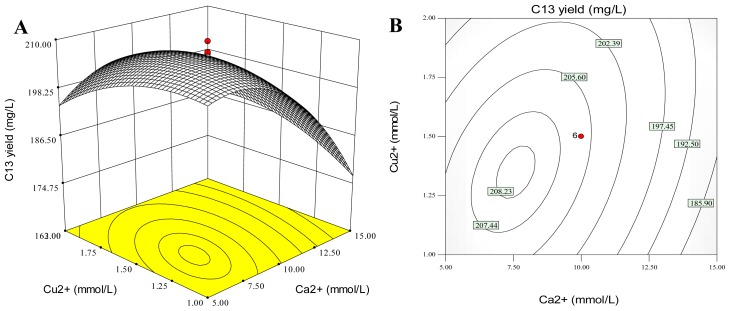

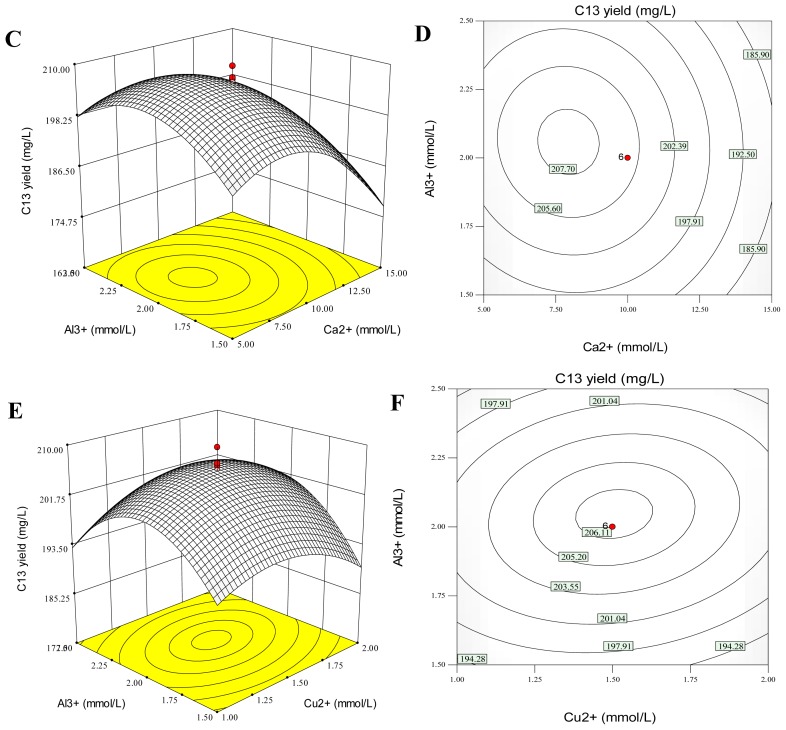

The three-dimensional (3D) response surface and two-dimensional (2D) contour plots are the graphical representations of the quadratic polynomial regression equation [49]. They provide a method to visualize the relationship between the responses and the experimental levels of each variable, and the interactions between any two test variables from the circular or elliptical nature of contour [50]. A circular contour plot indicates that the interactions between the corresponding variables are negligible. An elliptical nature of the contour plots indicates that the interactions between the corresponding variables are significant [51]. In this study, the 3D response surfaces and 2D contour plots of palmarumycin C13 field (mg/L) versus the metal ion concentrations (mmol/L) are presented in Figure 4, which were generated by employing the software of Design-Expert. Analyses of the 3D response surfaces and their corresponding 2D contour plots allowed us to conveniently investigate the interactions between any two variables, and locate the optimum ranges of the variables efficiently such that the response was maximized. The maximum predicted response was indicated by the surface confined in the smallest ellipse in the contour diagram.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional response surfaces (A, C and E) and two-dimensional contour plots (B, D and F) of palmarumycin C13 yield (mg/L) versus the test variables (mmol/L): Ca2+ and Cu2+ (A and B); Ca2+ and Al3+ (C and D); Cu2+ and Al3+ (E and F). Palmarumycin C13 was abbreviated as C13.

Figure 4A,B graphed the effects of Ca2+ and Cu2+ on palmarumycin C13 yield and their interactions when Al3+ concentration was fixed at zero level (2.0 mmol/L). A full elliptic contour in Figure 4B was observed, indicating a significant interaction between Ca2+ and Cu2+ for palmarumycin C13 production. When the concentrations of Ca2+ and Cu2+ in medium were increased from the lowest levels to the highest levels, palmarumycin C13 yield was increased initially and then decreased. Similar results appeared in Figure 4C,D, as well as in Figure 4E,F. Palmarumycin C13 yield was initially augmented and then decreased when the concentrations of two metal ions (either Ca2+ and Al3+ or Cu2+ and Al3+) varied from the lowest levels to the highest levels. The interactions either between Ca2+ and Al3+ or between Cu2+ and Al3+ were not significant. They were consistent with the analyses of coefficients of the regression equation (Table 6).

By analyzing the 3D response surface and 2D contour plots, the corresponding point to the maximum of palmarumycin C13 yield should locate on the peak of the response surface, which projected in the smallest ellipse in the contour diagram [52]. Hence, the optimal ranges of the concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ in medium for realizing the maximization of palmarumycin C13 yield were calculated by the software Design Expert as follows: 5.94 to 9.06 mmol/L for Ca2+, 1.24 to 1.63 mmol/L for Cu2+, and 1.86 to 2.15 mmol/L for Al3+.

By solving the inverse matrix of the regression polynomial equation (Equation 1) employing the software of Design-Expert, the optimum values for palmarumycin C13 yield of the test parameters in uncoded units were obtained as follows: Ca2+ as 7.58 mmol/L, Cu2+ as 1.36 mmol/L, and Al3+ as 2.05 mmol/L. Under the optimum conditions, the predicted palmarumycin C13 yield reached the maximum (208.49 mg/L). Under the determined conditions, a mean value of palmarumycin C13 yield of 203.85 mg/L (n = 5) was obtained from the actual experiments, slightly lower than the predicted maximum value (208.49 mg/L), and about 6.00-fold of the original yield (33.98 mg/L) in the original basal medium. Based on the Student t-test, the above model was satisfactory and adequate for reflecting the expected optimization as no significant difference was observed between the predicted maximum palmarumycin C13 yield and the experimental one.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Endophytic Fungus and Culture Conditions

The endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 (GenBank accession number EU543255) was isolated from the healthy rhizomes of the medicinal plant Dioscorea zingiberensis C. H. Wright (Dioscoreaceae) in our previous study [8,9]. The living culture has been deposited in China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) under the number of CGMCC 2476. It was also maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) slants at 4 °C. For preparation of the inoculum, four disks (about 5 mm) of the mycelia of Dzf12 were transferred into each Erlenmeyer flask (300 mL) containing 100 mL of potato dextrose broth. After 4 days’ cultivation on a rotary shaker in darkness at 150 rpm and 25 °C, the seed suspension cultures in three percent (v/v) were inoculated in Erlenmeyer flasks (150 mL) containing 30 mL of fermentation medium, which composed of glucose 40 g/L, peptone 10 g/L, KH2PO4 1.0 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 0.5 g/L and FeSO4·7H2O 0.05 g/L, pH 6.5. The Erlenmeyer flasks were incubated on a rotary shaker in darkness at 150 rpm and 25 °C for 13 days.

3.2. Application of the Metal Ions

Stock metal ion solutions were prepared by dissolving each inorganic salt (i.e., NaCl, CaCl2·2H2O, AgNO3, CoCl2·6H2O, CuCl2·2H2O, AlCl3·6H2O, ZnCl2, and MnCl4·4H2O) in distilled water. The solutions were sterilized by filtrating through a microfilter (pore size, 0.22 μm), diluted with sterile water into different concentrations, and then stored at 4 °C before use. Based on our preliminary experiments (data not shown), the metal ion solutions were added to three-day-old cultures. 100 μL of the stock solution was used as inoculum in 30 mL medium in the experiments with varying amounts of NaCl (final concentrations of Na+ in medium as 5, 10, 20 mmol/L), CaCl2·2H2O (final concentrations of Ca2+ in medium as 5, 10, 20 mmol/L), AgNO3 (final concentrations of Ag+ in medium as 0.05, 0.10 and 0.50 mmol/L), CoCl2·6H2O (final concentrations of Co2+ in medium as 0.05, 0.10 and 0.50 mmol/L), CuCl2·2H2O (final concentrations of Cu2+ in medium as 0.50, 1.50 and 3.00 mmol/L), AlCl3·6H2O (final concentrations of Al3+ in medium as 0.50, 1.50 and 3.00 mmol/L), ZnCl2 (final concentrations of Zn2+ in medium as 2.00, 4.00 and 8.00 mmol/L), MnCl4·4H2O (final concentrations of Mn4+ in medium as 2.00, 4.00 and 8.00 mmol/L), respectively. As Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ were found to be the most effective metal ions (data shown in Table 1), they were applied in the next experiments at five concentrations (1, 5, 10, 15 and 20 mmol/L for Ca2+; 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 3.0 mmol/L for Cu2+; 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 mmol/L for Al3+) on days 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12 of culture, respectively. Furthermore, Al3+ was added on day 3 of culture at six concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 mmol/L) to investigate its effect on palmarumycins C12 and C13 production. For investigating the combination effects of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ on palmarumycin C13 production, the final concentrations of the metal ions were set by the software of Design Expert and presented in Table 3.

3.3. Determination of Mycelia Biomass

The mycelia of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 were separated from the liquid medium by filtration under vacuum and rinsed thoroughly with distilled water, and then dried at 50–55 °C in an oven to a constant dry weight (dw).

3.4. Extraction and Quantification of Palmarumycins C12 and C13

Palmarumycin extraction and determination were carried out as previously described [10,29–31]. Briefly, 50 mg of dry mycelia powder was added into a tube with 5 mL of methanol-chloroform (9:1, v/v), and then subjected to ultrasonic treatment (three times, 60 min each). After removal of the solid by filtration, the filtrate was evaporated to dryness and re-dissolved in 1 mL of methanol. For quantitative analysis of palmarumycins C12 and C13 in broth, 3 mL of the culture broth without mycelia was evaporated to dryness and extracted with 5 mL of methanol-chloroform (9:1, v/v) in an ultrasonic bath (three times, 60 min each), and the liquid extract was then evaporated to dryness and re-dissolved in 1 mL of methanol.

Palmarumycin content was analyzed by the high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Shimadzu, Japan), which consisted of two LC-20AT solvent delivery units, an SIL-20A autosampler, an SPD-M20A photodiode array detector, and CBM-20Alite system controller. The reversed-phase Agilent TC-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., particle size 5 μm) was used for separation by using a mobile phase of methanol-H2O (50:50, v/v) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The temperature was maintained at 40 °C, and UV detection at 226 nm. The sample injection volume was 10 μL. The LCsolution multi-PDA workstation was employed to acquire and process chromatographic data. Palmarumycins C12 and C13 were detected and quantified with the standards prepared according to the method of Cai et al. [8] and Li et al. [10].

3.5. Experimental Design for the Combination Effects of the Metal Ions

Central composite design (CCD) experiments and response surface methodology (RSM) were employed to optimize the concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ in the fermentation medium for realizing the maximization of palmarumycin C13 yield by the software of Design-Expert. The metal ion solutions were added to 3-day-old cultures. 100 μL of the stock solution was used as inoculum in 30 mL medium in the experiments with varying amounts of CaCl2·2H2O, CuCl2·2H2O, and AlCl3·6H2O, respectively. Each independent variable (final metal ion concentration) in the CCD experiments was studied at five coded levels (−1.682, −1, 0, +1, +1.682), which is represented in Table 3. The independent variable was expressed as Xi, which was coded as xi, according to the following equation (Equation 2):

| (2) |

where xi is the coded value of the variable Xi, while X0 is the value of Xi at the center point, and ΔX is the step change of an independent variable.

CCD in this experimental design consisted of 20 trials which were carried out in a random order in triplicate that was necessary to estimate the variability of measurements, which are presented in Table 4. Five replicates at the center point of the design were carried out to allow for estimation of a pure error sum of squares. Palmarumycin C13 yield was recorded as the mean of triplicates, which was taken as the response value.

Based on the CCD experimental data, a second-order polynomial model was established, which correlated the relationship between palmarumycin C13 and the test independent variables. The relationship could be expressed by the following equation (Equation 3):

| (3) |

where Y is the predicted response value; a0 is the intercept term; x1, x2 and x3 are test independent variables; a1, a2 and a3 are linear coefficients; a12, a13 and a23 are cross-product coefficients; and a11, a22 and a33 are the quadratic term coefficients. All of the coefficients of the second polynomial model and the responses obtained from the experimental design were subjected to multiple nonlinear regression analyses.

The fitness of the second-order polynomial model equation was evaluated by the coefficient (R2) of determination. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) and test of significance for regression coefficients were conducted by F-test. In order to visualize the relationship between the response values and test independent variables, the fitted polynomial equation was separately expressed as 3D response surfaces and 2D contour plots by the software of Design Expert [53,54].

3.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the results were represented by their mean values and the standard deviations (SD). The data were submitted to analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) to detect significant differences by PROC ANOVA of SAS version 8.2. The term significant has been used to denote the differences for which p ≤ 0.05.

4. Conclusions

In this work, three metal ions (Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+) were screened from eight metal ions to show their stimulatory effects on mycelia growth and palmarumycins C12 and C13 production in liquid culture of the endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. When Ca2+ was applied to the medium at 10.0 mmol/L on day 3, Cu2+ to the medium at 1.0 mmol/L on day 3, Al3+ to the medium at 2.0 mmol/L on day 6, the maximal yields of palmarumycins C12 plus C13 were obtained as 137.57 mg/L, 146.28 mg/L and 156.77 mg/L, which were 3.94-fold, 4.19-fold and 4.49-fold in comparison with that (34.91 mg/L) of control, respectively. Meanwhile, Al3+ favored palmarumycin C12 production when its concentration was higher than 4 mmol/L. Ca2+ had an enhancing effect on mycelia growth of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. This is the first time the enhancing effect of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ on secondary metabolite production of fungi has been reported. Zn2+ slightly stimulated mycelia growth, and had no obvious effect on total palmarumycin production. The mycelia growth was strongly inhibited by Ag+ and Co2+, and slightly inhibited by Na+ and Mn4+. The inhibitory capacity of the metal ions Na+, Ag+, Co2+ and Mn4+ for palmarumycins C12 and C13 production was in the order of Co2+ > Ag+ > Mn4+ > Na+. Based on the results in this study, it was concluded that an enhancing effect could be determined by the metal ions (i.e., Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+) along with the combination of their addition time and concentration. The combination of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ for palmarumycin C13 production in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 was further optimized by employing a statistical method based on CCD and RSM. By solving the quadratic regression equation between palmarumycin C13 yield and three variables (i.e., the concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+), the optimal concentrations of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+ in medium for palmarumycin C13 production were determined as 7.58, 1.36 and 2.05 mmol/L, respectively. Under the optimum conditions, the predicted maximum palmarumycin C13 yield reached 208.49 mg/L. The predicted maximum values for palmarumycin C13 yield showed no significant differences from the experimental ones. By optimizing the combination of three metal ions in medium, palmarumycin C13 yield was increased to 203.85 mg/L, which was 6.00-fold in comparison with that (33.98 mg/L) in the original basal medium. The results indicate that enhancement of palmarumycin accumulation in liquid culture of Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 by the metal ions should be an effective strategy for large-scale production of palmarumycins in the future. As the combination effects of only three metal ions (i.e., Ca2+, Cu2+ and Al3+) have been studied for their enhancing effects on palmarumycin C13 production in this work, more components in the medium, as well as other parameters like pH, temperature, oxygen supply, and other ionic strengths, should be considered in future work. Furthermore, the action mechanisms of the metal ions on palmarumycin biosynthesis also need to be studied in detail. After a series of optimizations for palmarumyicn biosynthesis conditions, we could achieve the final optimized medium for maximum production of palmarumycins by natural fermentation of the endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. Furthermore, some biosynthetic mechanisms of palmarumycins should be helpful for our chemical synthetic methods, though some of those achieved are, at present, neither economically viable nor environmentally friendly [14,15].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31071710) and National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB126105) for their financial support in this research.

References

- 1.Aly A.H., Debbab A., Kjer J., Proksch P. Fungal endophytes from higher plants: A prolific source of phytochemicals and other bioactive natural products. Fungal Divers. 2010;41:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunatilaka A.A.L. Natural products from plant-associated microorganisms: Distribution, structural diversity, bioactivity, and implications of their occurrence. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:509–526. doi: 10.1021/np058128n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz B., Boyle C., Draeger S., Rommert A.K., Krohn K. Endophytic fungi: A source of novel biologically active secondary metabolites. Mycol. Res. 2002;106:996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kharwar R.N., Mishra A., Gond S.K., Stierle A., Stierle D. Anticancer compounds derived from fungal endophytes: their importance and future challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:1208–1228. doi: 10.1039/c1np00008j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L.-W., Zhang Y.-L., Lin F.-C., Hu Y.-Z., Zhang C.-L. Natural products with antitumor activity from endophytic fungi. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011;11:1056–1074. doi: 10.2174/138955711797247716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutierrez R.M.P., Gonzalez A.M.N., Ramirez A.M. Compounds derived from endophytes: A review of phytochemistry and pharmacology. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:2992–3030. doi: 10.2174/092986712800672111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J., Shan T., Mou Y., Zhou L. Plant-derived bioactive compounds produced by endophytic fungi. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011;11:159–168. doi: 10.2174/138955711794519492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai X., Shan T., Li P., Huang Y., Xu L., Zhou L., Wang M., Jiang W. Spirobisnaphthalenes from the endophytic fungus Dzf12 of Dioscorea zingiberensis and their antimicrobial activities. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009;4:1469–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang R., Li P., Zhao J., Yin C., Zhou L. Endophytic fungi from Dioscorea zingiberensis and their effects on the growth and diosgenin production of the host plant cultures. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2010;22:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Shan T., Mou Y., Li P., Zhao J., Zhao W., Peng Y., Zhou L., Ding C. Enhancement of palmarumycin C12 and C13 production in liquid culture of the endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 by oligosaccharides from its host plant Dioscorea zingiberensis. Molecules. 2012;17:3761–3773. doi: 10.3390/molecules17043761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krohn K., Michel A., Floerke U., Aust H.-J., Draeger S., Schulz B. Palmarumycins C1–C16 from Coniothyrium sp.: Isolation, structure elucidation, and biological activity. Liebigs. Ann. Chem. 1994;11:1099–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlingmann G., West R.R., Milne L., Pearce C.J., Carter G.T. Diepoxins, novel fungal metabolites with antibiotic activity. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7225–7228. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu M., Truumees I., Patel M.G., Gullo V.P., Blood C., King I., Pai J.K., Puar M.S. A novel class of anti-tumor metabolites from the fungus Nattrassia mangiferae. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1343–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou L., Zhao J., Shan T., Cai X., Peng Y. Spirobisnaphthalenes from fungi and their biological activities. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2010;10:977–989. doi: 10.2174/138955710792007178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai Y.-S., Guo Y.-W., Krohn K. Structure, bioactivities, biosynthetic relationships and chemical synthesis of the spirodioxynaphthalenes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:1840–1870. doi: 10.1039/c0np00031k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou L.G., Wu J.Y. Development and application of medicinal plant tissue cultures for production of drugs and herbal medicinals in China. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:789–810. doi: 10.1039/b610767b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L., Cao X., Zhang R., Peng Y., Zhao S., Wu J. Stimulation of saponin production in Panax ginseng hairy roots by two oligosaccharides from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007;29:631–634. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider P., Misiek M., Hoffmeister D. In vivo and in vitro production options for fungal secondary metabolites. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2008;5:234–242. doi: 10.1021/mp7001544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang R., Li P., Xu L., Chen Y., Sui P., Zhou L., Li J. Enhancement of diosgenin production in Dioscorea zingiberensis cell culture by oligosaccharide elicitor from its endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum Dzf17. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009;4:1459–1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu L., Liu Y., Zhou L., Wu J. Enhanced beauvericin production with in situ adsorption in mycelial liquid culture of Fusarium redolens Dzf2. Process Biochem. 2009;44:1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L., Liu Y., Zhou L., Wu J. Optimization of a liquid medium for beauvericin production in Fusarium redolens Dzf2 mycelial culture. Biotechnol. Bioproc. Eng. 2010;15:460–466. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J., Zhou L., Wu J. Effects of biotic and abiotic elicitors on cell growth and tanshinone accumulation in Salvia miltiorrhiza cell cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;87:137–144. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li P., Mou Y., Shan T., Xu J., Li Y., Lu S., Zhou L. Effects of polysaccharide elicitors from endophytic Fusarium oxysporum Dzf17 on growth and diosgenin production in cell suspension culture of Dioscorea zingiberensis. Molecules. 2011;16:9003–9016. doi: 10.3390/molecules16119003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li P., Mao Z., Lou J., Li Y., Mou Y., Lu S., Peng Y., Zhou L. Enhancement of diosgenin production in Dioscorea zingiberensis cell cultures by oligosaccharides from its endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum Dzf17. Molecules. 2011;16:10631–10644. doi: 10.3390/molecules161210631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metwally M., Abou-Zeid A. Effects of toxic heavy metals on growth and metabolic activity of some fungi. Egypt. J. Microbiol. 1996;31:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flores-Cotera L.B., Sanchez S. Copper but not iron limitation increases astaxanthin production by Phaffia rhodozyma in a chemically defined medium. Biotechnol. Lett. 2001;23:793–797. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y., Du J., Tsao G.T. Mycelial pellet formation by Rhizopus oryzae ATCC 20344. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2000;84:779–789. doi: 10.1385/abab:84-86:1-9:779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui Y.-H., Zhang K.-C. Effect of metal ions on the growth and metabolites production of Ganodenma lucidum in submerged culture. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011;10:11983–11989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao J., Zheng B., Li Y., Shan T., Mou Y., Lu S., Li P., Zhou L. Enhancement of diepoxin ζ production by yeast extract and its fractions in liquid culture of Berkleasmium-like endophytic fungus Dzf12 from Dioscorea zingiberensis. Molecules. 2011;16:847–856. doi: 10.3390/molecules16010847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao J., Li Y., Shan T., Mou Y., Zhou L. Enhancement of diepoxin ζ production with in situ resin adsorption in mycelial liquid culture of the endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 from Dioscorea zingiberensis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;27:2753–2758. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y., Li P., Mou Y., Zhao J., Shan T., Ding C., Zhou L. Enhancement of diepoxin ζ production in liquid culture of endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12 by polysaccharides from its host plant Dioscorea zingiberensis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28:1407–1413. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0940-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bode H.B., Wegner B., Zeeck A. Biosynthesis of cladospirone bisepoxide, a member of the spirobisnaphthalene family. J. Antibiot. 2000;53:153–157. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bode H.B., Zeeck A. UV mutagenesis and enzyme inhibitors as tools to elucidate the late biosynthesis of the spirobisnaphthalenes. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuero R., Ouellet T. Metal ions modulate gene expression and accumulation of the mycotoxins aflatoxin and zearalenone. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;98:598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei Q., Liu F., Zhang S., You T., Chen G., Wen L. Study on the relation between several metal ions and the growth metabolism of a symbiotic fungus of Sesarma bidens. Guangdong Weiliang Yuansu Kexue. 2012;19:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chardonnet C.O., Sams C.E., Conway W.S. Calcium effect on the mycelial cell walls of Botrytis cinerea. Phytochemistry. 1999;52:967–973. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berridge M.J., Bootman M.D., Roderick H.L. Calcium signaling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodeling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clapham D.E. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cavinder B., Hamam A., Lew R.R., Trail F. Mid1, a mechanosensitive calcium ion channel, affects growth, development, and ascospore discharge in the filamentous fungus Gibberella zeae. Eukaryotic Cell. 2011;10:832–841. doi: 10.1128/EC.00235-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tychanowicz G.K., Souza D.F., Souza C.G.M., Kadowaki M.K., Peralta R.M. Copper improves the production of laccase by the white-rot fungus Pleurotus pulmonarius in solid state fermentation. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2006;49:699–704. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsunoda K. Toxicity of aluminum and its speciation analysis. Biomed. Res. Trace Elem. 2005;16:276–280. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berthon G. Aluminum speciation in relation to aluminum bioavailability, metabolism and toxicity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002;228:319–341. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haque R.M., Kuo Y.-H., Lambein F., Hussain M. Effect of environmental factors on the biosynthesis of the neuro-excitatory amino acid β-ODAP (β-N-oxalyl-α,β-diaminopropionic acid) in callus tissue of Lathyrus sativus. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bejan C., Visoiu E. Resveratrol biosynthesis on in vitro conditions in grapevine (cv. Feteasca Neagra and Cabernet Sauvignon) Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011;16:S97–S101. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karimi F., Khataee E. Aluminum elicits tropane alkaloid production and antioxidant system activity in micropropagated Datura innoxia plantlets. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012;34:1035–1041. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pujari V., Chandra T.S. Statistical optimization of medium components for enhanced riboflavin production by a UV-mutant of Eremothecium ashbyii. Process Biochem. 2000;36:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao H., Gu W.-Y. Optimization of polysaccharide and ergosterol production from Agaricus brasiliensis by fermentation process. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007;33:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J.-Z., Weng L.-P., Zhan Q.-L., Xu H., Ji L.N. Optimization of glucose oxidase production by Aspergillus niger in a benchtop bioreactor using response surface methodology. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003;19:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Box G.E.P., Wilson K.B. On the experimental attainment of optimum conditions. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B. 1951;13:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiran B., Kaushik A., Kaushik C.P. Response surface methodological approach for optimizing removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solution using immobilized cyanobacterium. Chem. Eng. J. 2007;126:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muralidhar R.V., Chirumamila R.R., Marchant R., Nigam P. A response surface approach for the comparison of lipase production by Candida cylindracea using two different carbon sources. Biochem. Eng. J. 2001;9:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Y., Cui S.W., Tang J., Gu X. Optimizaiton of extraction process of crude polysaccharides from boat-fruited sterculia seeds by response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2007;105:1599–1605. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soto-Cruz O., Saucedo-Castaneda G., Pablos-Hach J.L., Gutierrez-Rojas M., Favela-Torres E. Effect of substrate composition on the mycelial growth of Pleurotus ostreatus. An analysis by mixture and response surface methodologies. Process Biochem. 1999;35:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Triveni R., Shamala T.R., Rastogi N.K. Optimized production and utilization of exopolysaccharide from Agrobacterium radiobacter. Process Biochem. 2001;36:787–795. [Google Scholar]