Abstract

Rrp44 (Dis3) is a key catalytic subunit of the yeast exosome complex and can processively digest structured RNA one nucleotide at a time in the 3’ to 5’ direction. Its motor function is powered by the energy released from the hydrolytic nuclease reaction instead of ATP hydrolysis as in conventional helicases. Single-molecule fluorescence analysis revealed that instead of unwinding RNA in single base pair steps, Rrp44 accumulates the energy released by multiple single nucleotide step hydrolysis-reactions until about four base pairs are unwound in a burst. Kinetic analyses showed that RNA unwinding, not cleavage or strand release, determines the overall RNA degradation rate, and that the unwinding step size is determined by the nonlinear elasticity of the Rrp44/RNA complex, but not by duplex stability.

The cellular levels of RNA species are tightly regulated by balancing transcription and degradation, controlling the temporal and spatial distribution of RNA (1). The exosome complex is a major player in the 3’ to 5’ RNA-degradation and -processing pathways (1, 2). In yeast, Rrp44, also named Dis3, is the only catalytically active component of the 10-subunit core exosome complex. Rrp44 is a multifunctional enzyme containing endo- and exo-ribonuclease activities which reside in two distinct regions (3, 4). The endonuclease activity of Rrp44 is carried out by the N-terminal PIN domain (3, 4). The RNA-binding CSD1, CSD2, and S1 domains, together with the RNB domain at its C-terminal region organize into a typical RNase II-type exoribonuclease (Fig. 1A) (5, 6). The exoribonuclease removes nucleotides (nt) one at a time in a processive manner from the 3’ end of RNA (7), and can unwind structured RNA for degradation. Structural and functional studies suggest an occlusion-based mechanism where a narrow entryway to the active site allows the passage of ssRNA but sterically restricts dsRNA (5, 6). Unwinding of the duplex is presumably achieved by a translocation of the exonuclease active site pulling the 3’ tail at the junction of the RNA duplex (ds-ss junction) (6). Rrp44 can be considered as a 3’ to 5’ RNA helicase except that its translocation seems powered by the chemical energy released from hydrolysis of the RNA chain, thus it burns its own track.

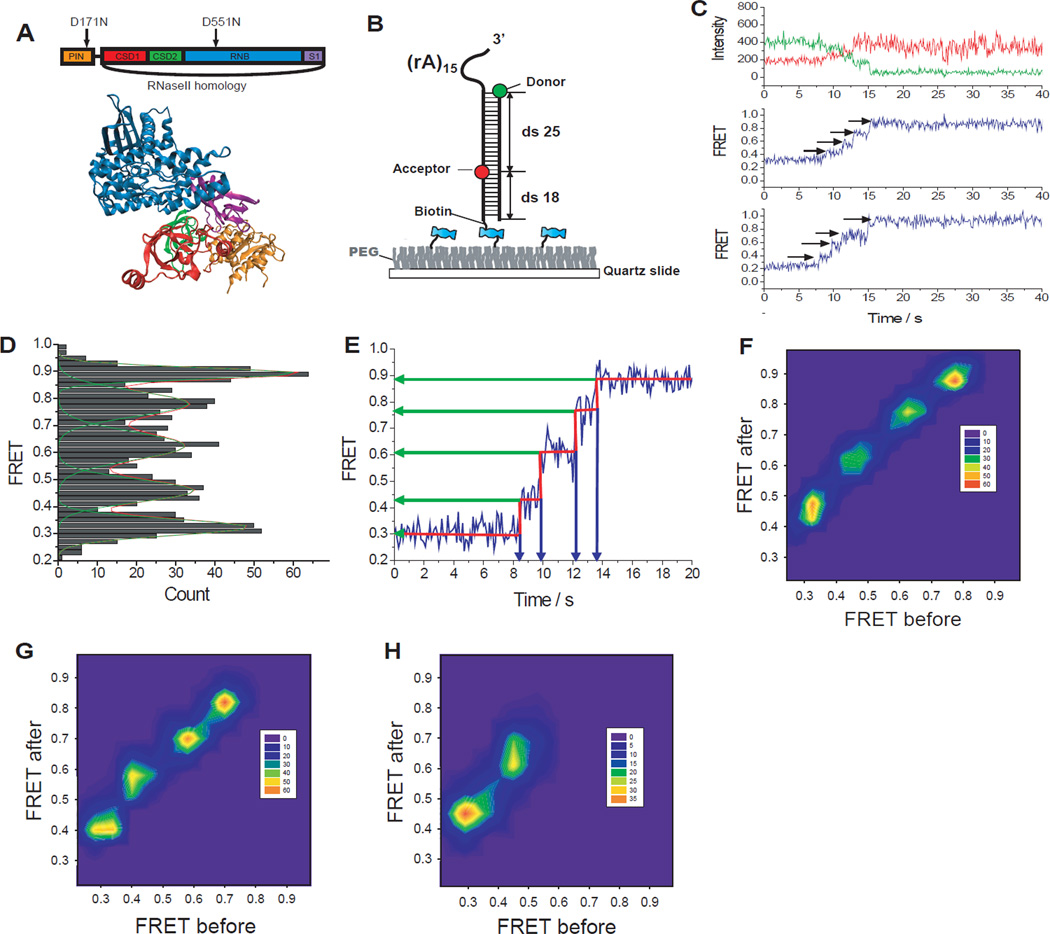

Fig. 1.

Rrp44 unwinds RNA in large discrete steps. (A) Structure of Rrp44 and its domain map. (B) GC-rich (60%) construct was labeled with donor (Cy3) at the ds-ss junction and acceptor (Cy5) at the 25 bp downstream from the donor. (C) Representative fluorescence intensity (top, green for donor and red for acceptor) and FRET efficiency (middle and bottom) time trajectories show step-wise FRET increase during dsRNA unwinding. (D) Distribution of each FRET state visited during unwinding determined using an automated step-finding algorithm (209 molecules). (E) FRET values and dwell times at each step were quantified by an automated fitting step-finding algorithm (red, fig. S4). (F–H) Transition density plots pictorialize FRET changes before and after transitions for the GC-rich (60%) construct (F), GA-only RNA duplex (G, see fig. S5), and Chimera1 (H, see fig. S6).

How does Rrp44 couple its processive nuclease activity with duplex unwinding? Does it unwind a single base pair of RNA each time it cleaves a single nucleotide? Similar mechanistic questions have been debated for ATP-dependent helicases (8–12). To address these questions, we developed an RNA unwinding assay based on single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (13). The RNA substrate is a duplex RNA (60% GC content, 43 base-pairs); the substrate strand further contains a 3’-(A)15 overhang for Rrp44 loading to initiate degradation (Fig. 1B). The donor fluorophore (Cy3) is placed at the 5’-end of the complementary strand to mark the beginning of the duplex, and the acceptor fluorophore (Cy5) is placed 25 base-pairs (bp) into the duplex on the substrate strand. The annealed RNA was immobilized on a polymer-coated quartz surface via a biotin-streptavidin interaction and imaged using a two-color total internal reflection fluorescence microscope. The RNA construct was incubated with Rrp44 protein (~30 nM) in the absence of Mg2+ for ~2 minutes at room temperature to load the enzyme, and the reaction was initiated by flowing in 100 µM Mg2+. The flow also removed free proteins in solution so only the pre-bound Rrp44 contributes to the reaction. Degradation of the substrate strand triggers RNA duplex unwinding, and the displaced donor-containing complementary strand experiences larger conformational freedom, which causes an increase in FRET due to a decrease in the time averaged distance between the two fluorophores (14–16).

Indeed, upon addition of Mg2+, we observed a FRET increase (Fig. 1C and fig. S1). Interestingly, FRET increased with a discrete stepwise pattern that most commonly exhibited four apparent steps (Fig. 1.C and fig. S1) (17) in contrast to the smooth FRET changes observed during single stranded RNA degradation by an archaeal exosome (18). To determine whether the endo- or exo-ribonuclease activity of Rrp44 is responsible for the stepwise FRET increases, we tested four mutants: Rrp44D171N (endonuclease mutant), Rrp44ΔNPIN (N-terminal PIN domain deletion mutant), Rrp44D551N (exonuclease mutant) and Rrp44D171N, D551N (double mutant in both active sites). The FRET increase was not observed from Rrp44D171N, D551N or Rrp44D551N whereas a similar stepwise FRET increase was observed from Rrp44D171N and Rrp44ΔNPIN (fig. S2). We therefore attribute the stepwise FRET increases to the exoribonuclease activity of Rrp44. A gel assay confirmed that the enzyme indeed unwinds and degrades the 25 nt region flanked by the fluorophores (fig. S3).

To quantify the stepwise behavior in an unbiased way, we used an automated step-finding algorithm (9, 19) to determine the average FRET values and dwell times of each step (fig. S4 and Fig. 1, D and E). The histogram of FRET states obtained from the automated analysis (209 molecules that showed four steps) revealed five peaks, suggesting that well-defined FRET states are visited during unwinding (Fig. 1D). A transition density plot (TDP) (20), which pictorializes the two-dimensional histogram for pairs of FRET values before and after each transition (Fig. 1F), also indicates a discrete step size.

To test the possibility that the stepwise pattern may originate from secondary structure formation within the complementary strand liberated during unwinding, we designed a duplex construct where the complementary strand contained only Gs and As such that self-secondary structure is unlikely to form. Single molecule traces (fig. S5) and TDP (Fig. 1G) revealed the same stepwise pattern, indicating that the stepwise pattern is intrinsic to the unwinding reaction and is not a sequence-specific feature.

To define the physical parameters of the stepwise unwinding observed, we utilized RNA/DNA chimeric substrate strand where RNA degradation cannot continue beyond the first 7 or 15 nt of the substrate strand in the duplex region (fig. S6). The two constructs gave two and four steps of unwinding respectively, suggesting an unwinding step size of about 4 [=(15-7)/(4-2)] bp. The 7 nt chimeric construct showed the highest FRET value of ~ 0.64. If Rrp44 unwinds the dsRNA only up to the boundary between RNA and DNA segments, a FRET value of ~0.48 is expected based on a calibration construct (fig. S6B), which is much lower than the actual final FRET value of ~0.64. This indicated that the Rrp44 unwinds the duplex ahead of the degradation site, consistent with the structural data that showed ~7 nt of ssRNA is required to reach the active site through a passage too narrow for the RNA duplex (5, 6).

We then analyzed the dwell time of each step (Fig. 2A). If the unwinding itself is rapid and cleavage reactions are rate-limiting, the dwell time histogram would follow a gamma distribution with a rising phase and a decaying phase because it would be composed of about four equivalent steps that are irreversible (Fig. 2B) (9). In contrast, if unwinding is rate-limiting and cleavage reactions are fast, it would follow a single exponential decay (Fig. 2C). The dwell time histogram showed a single exponential decay with a lifetime of ~1.6 s, indicating that unwinding of ~4 bp occurs in a burst with a single rate-limiting step (Fig. 2, C and D, and fig. S7).

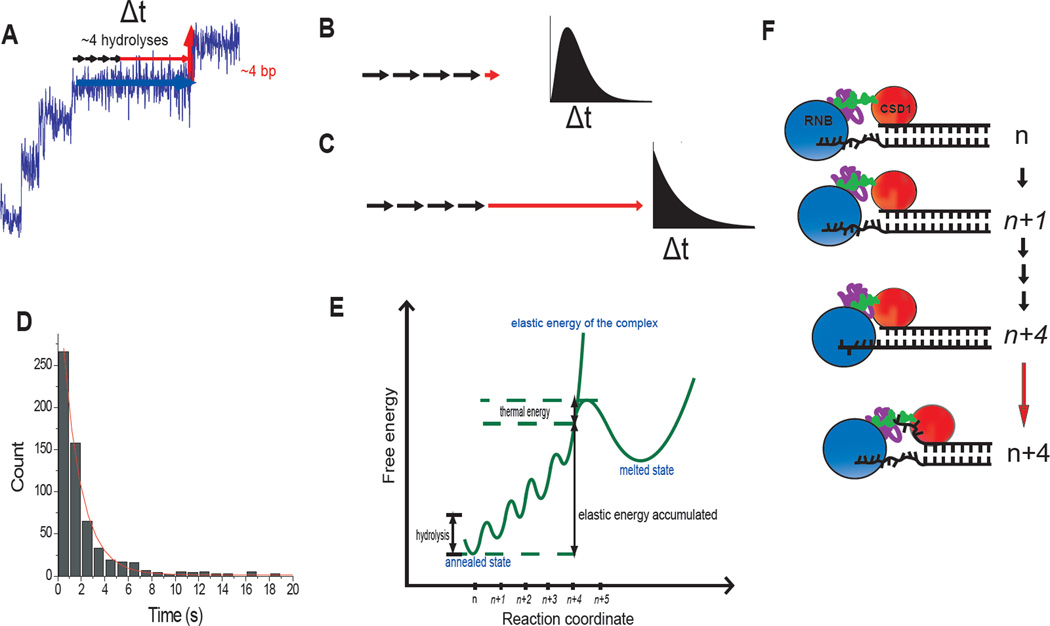

Fig. 2.

Elastic coupling between RNA degradation and unwinding. (A) Each unwinding step consists of ~4 degradation steps (black arrows) and a wait time (horizontal red arrow). (B) If dsRNA is unwound immediately after a series of cleavage reactions, the dwell time histogram follows a gamma-distribution distribution. (C) If unwinding occurs after a long delay, the histogram follows a single exponential-like decay. (D) Histogram of the dwell times in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th steps. Exponential fit gives 1.6 s decay time (See fig. S7 for individual histograms). (E) Elastic energy accumulated vs. number of nucleotides digested without duplex unwinding. (F) Structural model on how the RNB domain that contains the exonuclease activity and the putative dsRNA binding domain (CSD1) might allow the build-up of elastic energy during ~ 4 cleavage reaction until abrupt unwinding of ~ 4 bp resets the system for the next cycle. In (E) and (F), the states with accumulated elastic energy are italicized.

By combining our finding that Rrp44 unwinds dsRNA in ~4 bp steps in a burst, the available biochemical data that showed that Rrp44 digests RNA into single nucleotides, and the structural information (5, 6), we propose the following mechanism (Fig. 2, E and F). When Rrp44 encounters a ss/dsRNA junction, the exonuclease activity residing in the RNB domain can continue to degrade an additional ~4 nt in single nucleotide steps while one of the RNA binding domains, for example CSD1, maintains a contact with the duplex ahead, possibly stabilizing it (Fig. 2F and fig. S8). This would pull in the 3’ ssRNA tail without unwinding, resulting in an accumulation of elastic energy in the RNA-protein complex. Through thermal activation, Rrp44 then unwinds several base-pairs in a burst, releasing the elastic energy with an accompanying movement of the CSD1 domain. Rrp44 then continues this cycle to traverse the double-stranded RNA region (Fig. 2, E and F). This model predicts that if duplex melting is prevented, the substrate strand would still be degraded until much less than 7 nt is left on the 3’ overhang of the substrate strand. Gel-based RNA degradation experiment using a substrate with the first basepair of the duplex cross-linked to each other confirmed this prediction (fig. S9).

Next, we examined how the dwell time in each step or the unwinding step size is affected by duplex stability. First, an RNA-DNA hetero-duplex was used in which the substrate RNA strand remains the same but the complementary strand is DNA (fig. S10). FRET traces also showed 4 distinct steps at similar FRET values, suggesting that the unwinding step size remains the same (fig. S10). However, the average dwell time at each step was ~60% shorter than that of the all RNA duplex (fig. S11). The difference cannot be attributed to a difference in degradation rate because the substrate RNA strand is identical. Therefore, the less stable hetero-duplex (21) is unwound faster, further showing that unwinding, but not degradation, is rate-limiting. The elastic energy accumulated would be the same but the total free energy barrier is lower for the RNA-DNA hybrid so it takes less time for thermal fluctuations to overcome the barrier (Fig. 2E).

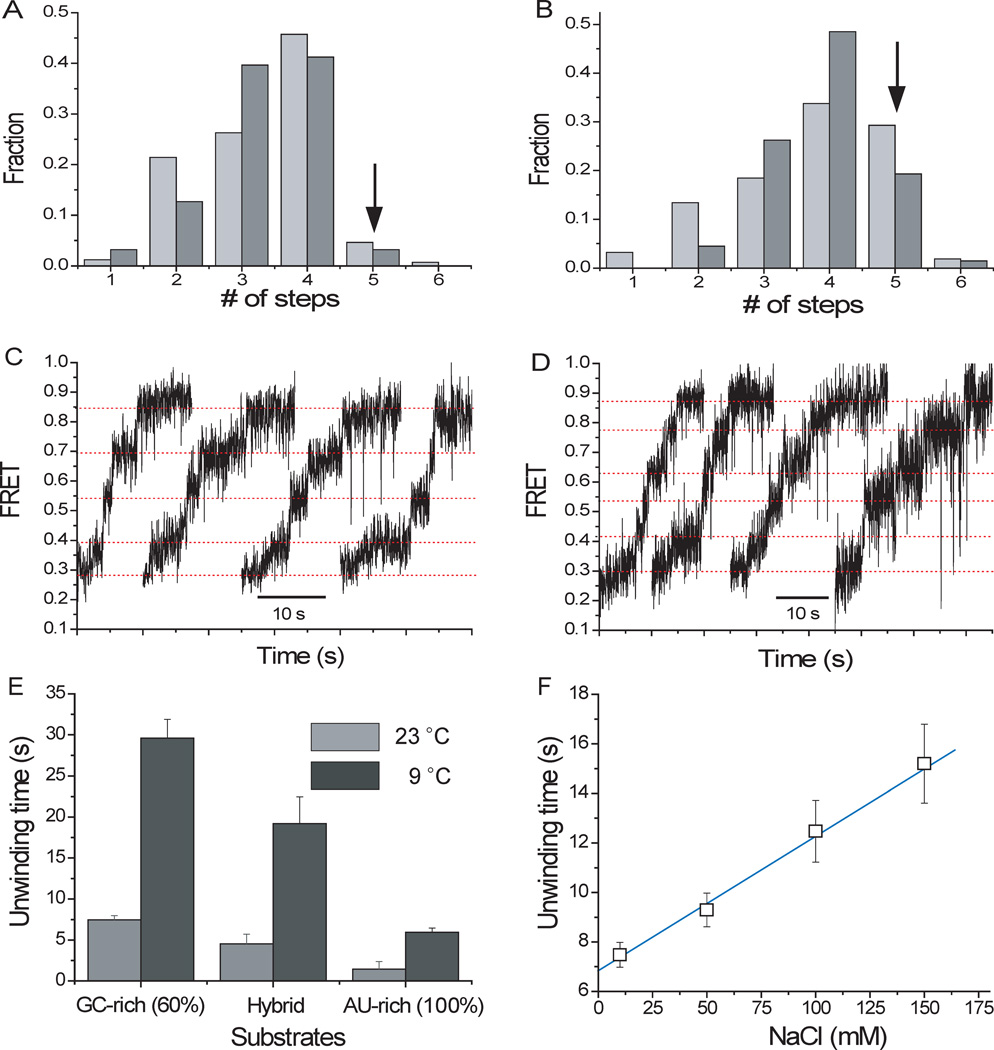

We also tested a construct with 100% AU base pairs in the RNA duplex. Its unwinding at room temperature was too fast for resolving steps clearly (fig. S12B). Lowering the temperature or increasing the magnesium concentration decreased the reaction speed sufficiently to show hints of stepwise unwinding (fig. S12C and S12D). We therefore performed experiments in 5 mM MgCl2 at ~9°C and found that the four-step pattern is the dominant unwinding behavior for the AU-rich (100%) construct as well. We also observed a significantly increased fraction of five-step degradation patterns (~19%) (Fig. 3, A and B), suggesting that there may exist an occasional, premature unwinding event before a ~4 nt digestion is achieved if the duplex is less stable.

Fig. 3.

Unwinding characteristics for different sequences and conditions. (A) Distribution of the number of steps for the standard substrate (60% GC content) (light gray: at 22 °C; dark gray: 9 °C, both in 100 µM MgCl2). (B) Distribution of the number of steps for the AU-rich construct (light gray: 23°C; dark gray: 9°C, both in 5 mM MgCl2). (C–D) Representative four and five - step patterns, respectively, obtained from AU-rich construct in 5 mM MgCl2 at 9 °C. (E) Unwinding for different constructs and temperatures. (F) Unwinding time vs. NaCl concentration for the standard substrate.

We determined the overall unwinding time, τunwind, defined as the time it takes for the FRET signal to increase from minimum to maximum, for different substrates and conditions (Fig. 3E). τunwind was 4-fold longer at 9°C than at 22°C for all three constructs. τunwind increased by a factor of 2 when the NaCl concentration was increased from 10 mM to 150 mM (Fig. 3F), whereas it increased 4-fold when the MgCl2 concentration was increased from 0.1 mM to 5 mM (fig. S12A). Overall, reducing the duplex stability decreases the dwell time of each step without changing the step size, indicating that unwinding is rate-limiting and that the discrete steps in FRET trajectories are due to steps in unwinding rather than other effects such as release of unwound strand from the protein surface (11).

How large a distortion would the RNA-protein complex accumulate before an unwinding burst? Because the A-form RNA double helix has a helical pitch of 2.5 nm and 11 bp per turn (22), the step size of ~4 bp is equivalent to ~0.9 nm in length. Therefore, a distortion of up to ~ 1 nm would need to be accommodated, either by ssRNA stretching or through protein compression (which may be achieved through reorganization of various domains of Rrp44), or a combination of both.

What determines the step size of RNA unwinding? For degradation to continue without strand separation, there must be a large kinetic barrier against duplex melting, which may originate from interactions between the RNA and one of the RNA binding domains (Fig. 2F and fig. S8). Most proteins and ssRNA are nonlinear springs (23, 24), thus the elastic energy of the complex would increase dramatically at a particular length which might determine how many nucleotides can be degraded before the elastic energy overcomes the kinetic barrier and unwinds the duplex (Fig. 2E). If so, unwinding step size would be determined by the physical properties of the Rrp44/RNA complex.

We propose that the RNB domain acts as “an engine” that converts chemical energy into mechanical work by translocation along the RNA. Rrp44 functions as “a chemo-mechanical machine” that converts and combines a series of chemical energy releases from hydrolysis of the RNA chain into an elastic energy reserve through a spring loaded mechanism until several base pairs are unwound in bursts. This mode of action may also apply to yeast Rrp44 in complex with the 9-subunit core exosome depending on how RNA is delivered to Rrp44 (25, 26) and to the human Rrp44 proteins that either interact weakly with the 9-subunit core exosome or not at all (27). Elastic coupling between RNA digestion and unwinding may be common in RNase II-type exonucleases as we found similarly sized steps in RNA unwinding by E. coli RNaseR (fig. S13). Many helicases possess auxiliary domains, besides the core ATPase, that may display spring-like behavior so that a single nucleotide step translocation can yield an unwinding step size of several base pairs as was proposed for HCV NS3 (9). The concept that nucleic acid motors can have a hierarchy of different sized steps or can accumulate elastic energy before transitioning to a subsequent phase (8–10, 28–30) is further supported by our data on Rrp44.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Park, R. Vafabakhsh, A. Jain, S. Park, R. Zhou, X. Shi, M. Comstock and S. Syed for helpful discussions; J. Yoo, C. Maffeo and S. Arslan for experimental help. We also thank K. Lee for the data acquisition program. Funds were provided by grants from National Science Foundation (0646550, 0822613 to T.H.) and National Institutes of Health (GM065367 to T.H. and GM-086766 to A.K.). G.L. was supported by the Jane Coffin Childs Medical Institute. T.H. is an investigator with Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References and Notes

- 1.Houseley J, LaCava J, Tollervey D. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7:529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanacova S, Stefl R. Embo Reports. 2007;8:651. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebreton A, Tomecki R, Dziembowski A, Seraphin B. Nature. 2008;456:993. doi: 10.1038/nature07480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaeffer D, et al. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2009;16:56. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frazao C, et al. Nature. 2006;443:110. doi: 10.1038/nature05080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorentzen E, Basquin J, Tomecki R, Dziembowski A, Conti E. Molecular Cell. 2008;29:717. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dziembowski A, Lorentzen E, Conti E, Seraphin B. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2007;14:15. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali JA, Lohman TM. Science. 1997;275:377. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myong S, Bruno MM, Pyle AM, Ha T. Science. 2007;317:513. doi: 10.1126/science.1144130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz A, et al. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2009;16:1309. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng W, Arunajadai SG, Moffitt JR, Tinoco I, Jr., Bustamante C. Science. 2011;333:1746. doi: 10.1126/science.1206023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JY, Yang W. Cell. 2006;127:1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha T, et al. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 1996;93:6264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MC, Rasnik I, Cheng W, Lohman TM, Ha TJ. Biophysical Journal. 2004;86:2530. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu SX, Abbondanzieri EA, Rausch JW, Le Grice SFJ, Zhuang XW. Science. 2008;322:1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1163108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee G, Yoo J, Leslie BJ, Ha T. Nature Chemical Biology. 2011;7:367. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Among all FRET traces obtained, more than 45% traces shows four apparent steps. The step analysis suggests that the most of the rest of traces also may have a four step behavior but some of them are sometimes missing because they are faster than our time resolution (Fig. S2).

- 18.Lee G, Hartung S, Hopfner KP, Ha T. Nano Letters. 2010;10:5123. doi: 10.1021/nl103754z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerssemakers JWJ, et al. Nature. 2006;442:709. doi: 10.1038/nature04928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinney SA, Joo C, Ha T. Biophysical Journal. 2006;91:1941. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesnik EA, Freier SM. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10807. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickerson RE, et al. Science. 1982;216:475. doi: 10.1126/science.7071593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Granzier HL, Bustamante C. Science. 1997;276:1112. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seol Y, Skinner GM, Visscher K, Buhot A, Halperin A. Physical Review Letters. 2007;98 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.158103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang HW, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:16844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705526104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonneau F, Basquin J, Ebert J, Lorentzen E, Conti E. Cell. 2009;139:547. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomecki R, et al. Embo Journal. 2010;29:2342. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moffitt JR, et al. Nature. 2009;457:446. doi: 10.1038/nature07637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revyakin A, Liu CY, Ebright RH, Strick TR. Science. 2006;314:1139. doi: 10.1126/science.1131398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapanidis AN, et al. Science. 2006;314:1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1131399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.