Abstract

NS3 is an essential helicase for replication of Hepatitis C virus, and is a model enzyme for investigating helicase function. Using single molecule fluorescence analysis, we show that NS3 unwinds DNA in discrete steps of approximately 3-bp. Dwell time analysis indicates that about three hidden steps are required before a 3-bp step is taken. Combined with available structural data, we propose a spring-loaded mechanism where several 1 nt/ATP steps accumulate tension on the protein/DNA complex which is relieved periodically via a burst of 3 bp unwinding. NS3 appears to shelter the displaced strand during unwinding, and upon encountering a barrier or after unwinding >18 bp, it snaps/slips backward rapidly and repeats unwinding many times in succession. Such repetitive unwinding behavior over a short stretch of duplex may help keep secondary structures resolved during viral genome replication.

In Hepatitis C virus (HCV), non-structural protein 3 (NS3) is an essential component of the viral replication complex, and works with the polymerase (NS5B) and other protein cofactors (such as NS4A, NS5A and NS2) to ensure effective copying of the virus. The NS3 protein is a bifunctional enzyme that contains both protease and helicase domains (1–3) and is unusual in that it can unwind both DNA and RNA substrates (4, 5). Unwinding of the highly structured RNA genome of HCV is likely to be the major role for the NS3 helicase, however it remains possible that activity toward host DNA substrates plays a role in viral function. Indeed, NS3 rapidly binds DNA and unwinds it processively (6). Given these facts, combined with the availability of crystallographic data on NS3-DNA complexes (7–9), we chose to elucidate the elementary steps and kinetic mechanisms involved with NS3 unwinding of DNA.

In a previous ensemble study, NS3 was observed to unwind RNA with a physical and kinetic size of ~18 bp (10). More recently, single molecule mechanical studies under assisting force confirmed the periodic nature of RNA unwinding by NS3, but displayed rapid ~3–4 bp steps that were interrupted by long pauses approximately every 11 bp (11). These large apparent steps by NS3 contrast with structural studies of other helicases, which suggest that the elemental step for helicase activity is unwinding of a single base pair, and that this is linked to individual ATP hydrolysis events (12, 13). Nonetheless, there is no functional data supporting the existence of single base-pair unwinding steps, and no information on how they might correlate with the larger steps that appear to be involved in mechanical function of helicase enzymes (14).

Here, we employ single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to resolve the individual steps of DNA separation catalyzed by NS3 in the absence of applied force. Our standard substrate, PD1, is a partial duplex DNA (18 bp) with a 3′ ssDNA tail (20 nt). The donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) fluorophores are attached to the junction through amino-dT without interrupting the DNA backbone. The DNA is tethered to a polymer-passivated quartz surface via biotin at the 3′ tail terminus (Fig. 1A). After incubating this assembly with full-length NS3 protein (25nM) for 15 min, 4 mM ATP solution was flowed into the cell to initiate DNA unwinding. The flow of ATP also serves to remove unbound protein in solution and thereby allows us to monitor unwinding by pre-bound NS3 (15).

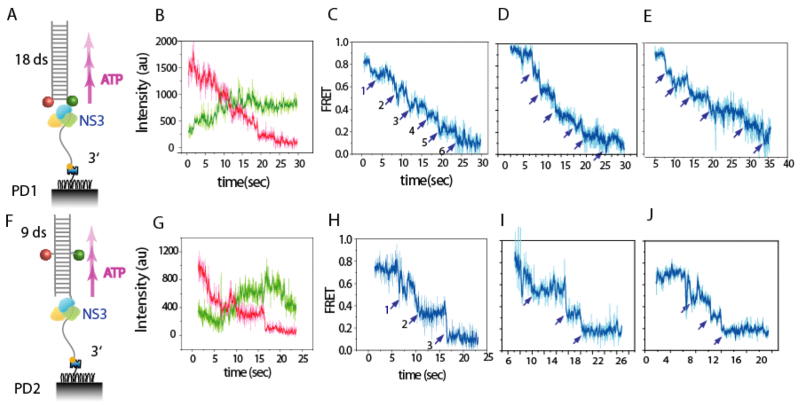

Fig. 1.

NS3 unwinds DNA in three basepair steps. (A) PD1, a DNA with 18/20 double/single strand (ds/ss) was labeled with donor (Cy3), acceptor (Cy5) at the ds/ss junction and was tethered to a PEG surface by 3′ biotin. (B) Cy3 (green) and Cy5 (red) intensities monitored during unwinding of a single PD1 molecule. (raw time traces in light colors and 3 point averaged traces in dark colors) (C) Calculated FRET efficiency vs. time for the molecule shown in (B). (D,E) Two more example FRET traces of PD1. (F) PD2 is the same construct of 18/20 (ds/ss) prepared with dyes in the middle of duplex. (G–J) Equivalent plots to (B–D) for PD2.

After addition of ATP, we observed a FRET decrease that is caused by the increase in the time averaged (30 ms time resolution) inter-fluorophore distance as the DNA is unwound. The measurements taken at 37°C indicate a rapid FRET decrease that appears to involve intermediate steps (Fig. S1). When the temperature was lowered to 30°C to slow down the reaction, FRET values decreased with a discrete pattern that is marked by apparent plateaus corresponding to six steps for unwinding of the 18 bp duplex (Fig. 1B–E). The same experiment was then performed with an otherwise identical substrate, PD2, in which the fluorophores were relocated 9 bp away from the junction, such that FRET signal is sensitive only to the final 9 bp unwinding (Fig. 1F). Plateaus were also observed in that case, although they occur with larger FRET increments that correspond to three unwinding steps for unwinding 9 bp (Fig. 1G–J). Both sets of data are consistent with a 3 bp unwinding step size. The data also indicate that the two strands do not spontaneously separate when only a few bp remain (i.e. via thermal duplex fraying). At the end of each experiment, the displacement of acceptor-labeled strands was confirmed by a direct excitation with a red laser.

In order to quantify the stepping behavior, we employed an automated step finding algorithm (16)(Fig. S2), which yielded the average FRET values for each plateau and its dwell time (Fig. 2A, D). We then built transition density plots (17), which represent the two-dimensional histogram for pairs of FRET values before (FRETenter) and after (FRETexit) each transition. Six and three well-isolated peaks emerged for 18 bp and 9 bp unwinding, respectively (about 75 molecules each) (Fig. 2B, E). The highest FRET peak region (Fig. 2B) appears to be in broader distribution than other peak regions possibly due to the NS3 binding and fluctuating or partially melting the junction and thus slightly separating the two dyes. This analysis demonstrates that there are well-defined FRET states that are visited sequentially during unwinding and that they are each separated by about 3 bp. Similar evidence for 3 bp unwinding steps was found for unwinding an 18 bp duplex of unrelated sequence (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Three base pair steps are composed of three hidden steps. (A) A step finding algorithm was used to quantify FRET values (orange arrows) and dwell times (blue arrows, Δt) at each step for a single molecule of PD1. (B) FRET values obtained from 75 molecules of PD1 were combined to make total density plot. (C) Gamma distribution fitting of the collected dwell times at each plateau pause duration for PD1 yielded approximately three irreversible steps (n value) within the three base pair step, indicating a strong possibility of one nucleotide as an elementary step size. (D–F) Equivalents plots to (A–C) for PD2.

If 3 base pairs is the elementary step size of unwinding, for example due to the hydrolysis of a single ATP, the dwell time histogram of the steps would follow a single exponential decay. In contrast, we obtained non-exponential dwell time histograms that displayed a rising phase followed by a decay (Fig. 2C, F). Assuming that each 3 bp step requires n hidden irreversible Poissonian steps with identical rate k, the data can be fit with the gamma distribution, tn-1 e−kt. The fits gave n = 2.84 for 18 bp and n = 2.72 for 9 bp unwinding. The k values were 0.78 s−1 and 0.89 s−1 respectively. These rates are similar to the unwinding rate estimated from an earlier bulk solution study of an 18 bp duplex of unmodified DNA (0.66 s−1 per bp) (6). Dwell time histograms built for individual steps gave similar n and k values for each step (Fig. S4). Overall, our data suggest that each 3 bp step is composed of three hidden steps of one bp, presumably due to 1 ATP hydrolysis each. The emerging model here is that, after three successive ATP hydrolysis events, there occurs an abrupt 3 bp separation.

The helicase domain of NS3 (NS3h), belonging to superfamily 2 (SF2), has three domains. Domain 1 and domain 2 have RecA-like folds and there is an ATP binding pocket between the domains. In the crystal structure of NS3h bound to (dU)6, domain 1 and 2 make contacts exclusively to the phosphate-ribose backbone of (dU)6 with no contact to the bases (9). Nevertheless, bases are well-resolved in the structure and there is enough room for duplex formation on the 5′ side with only a minor change in the relative position of domain 3. The structure, obtained in the absence of ATP, shows that two highly conserved threonines (T269, T411) bind to two phosphates that are located 3 nt apart. Mutation of either of these NS3 threonines abolishes unwinding activity (18). By contrast, the Vasa helicase and eIF4AIII structures, determined with AMPPNP and ADPNP bound respectively (19, 20), suggest that domain 1 and 2 will close upon ATP binding and that this would bring the equivalent two threonine residues 2 nt apart (Fig. S5A-C). This change in the distance between threonine contacts may represent the structural basis for a 1nt movement: Each ATP binding and product release event is expected to result in the 1 nt movement of domain 1 and 2 in the 3′ to 5′ direction.

Domain 3 presents a tryptophan (W501) that is critical for activity. The importance of an aromatic residue at this position is demonstrated by the fact that it can be substituted with phenylalanine, whereas alanine disrupts unwinding (18). The W501 stacks against the base at the 3′ end of (dU)6 (Fig. S5A) which might keep the relative position of domain 3 and DNA fixed while domain 1 and 2 translocate. This effect would lead to the build-up of tension both on the protein and the DNA which we propose is released after 3 nt translocation by a sudden movement of domain 3, with concomitant 3 bp unwinding of the DNA (Fig. S9).

SF1 helicases such as Rep, UvrD and PcrA are structurally analogous to SF2 helicases with superimposable domain arrangement and catalytic site (21, 22). The available crystal structures of SF1 helicases (Rep, UvrD and PcrA) all have well conserved threonine pairs and an aromatic gatekeeper residue, phenylalanine at the analogous locations to NS3 (Fig. S5D, E). ATP bound UvrD has the two threonines 2 nt apart whereas Rep with no ATP shows the threonines 3 nt apart, again supporting the 1 nt movement coupled to one ATP consumption.

In order to observe the unwinding behavior when the duplex end is challenged with a presence of physical blockade, we next examined unwinding of an inverted configuration where the duplex end was tethered to the surface via biotin-streptavidin (Fig. 3A). In this construct we swapped the dye positions so that the donor was attached to the displaced strand and the acceptor on the tracking strand. At 37 °C, the same stepwise behavior was observed but the unwinding could not be completed, perhaps due to steric hindrance by the biotin-streptavidin blockade. Some molecules (25%) showed the displaced strand (donor attached strand) remaining in contact with the enzyme for long periods (Fig. S6A) after unwinding, whereas many others (75%) displayed a repetitive FRET pattern as shown in Fig. 3B. In most cases, the peaks were asymmetric with an abrupt FRET increase followed by a gradual FRET decrease. We interpret this characteristic pattern as repeated trials of helicase unwinding followed by rapid rezipping/reannealing of the duplex. Since the unwinding reaction initiated after washing out free protein, such repetition likely arises from one unit rather than successive binding of different molecules. Could it be that the enzyme bears a secondary binding site that enables it to snap back to restart the next round of unwinding?

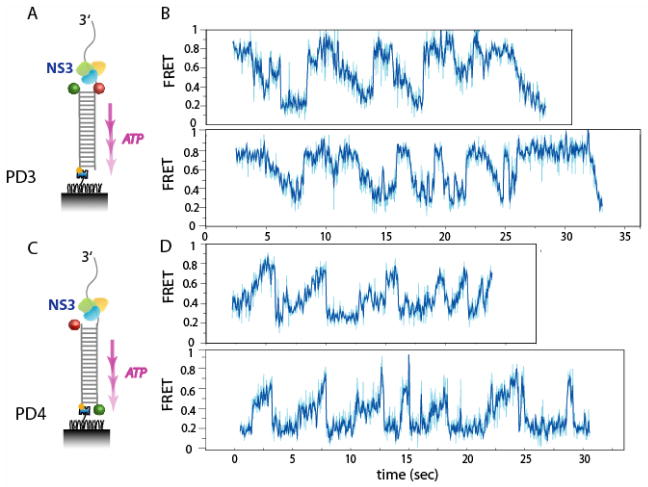

Fig. 3.

Repetitive unwinding of a short duplex stretch. (A) Partial duplex with ds18 and ss30 tail with cy3 and cy5 at ds/ss junction was blocked at the duplex end via biotin-streptavidin (PD3). (B) Majority of molecules (75%) showed repetitive unwinding pattern where the enzyme appear to snap/slip back to near junction upon encountering a blockade. (C) Partial duplex with ds18 and ss20 tail was labeled with cy5 at the ds/ss junction and cy3 at the end of duplex end (PD4). (D) The repetitive cycles of gradual FRET increase followed by a rapid decrease indicates that the displaced strand is brought close to the duplex end by NS3, then snaps/slips back to the junction rapidly after encountering the blockade.

We therefore designed a substrate such that whereabouts of the acceptor-labeled 5′ end of the displaced strand can be monitored via FRET from the donor at the duplex end. (Fig. 3C) In this experiment, we observed a repeating pattern in the shape of an asymmetric sawtooth where each peak involved a gradual rising phase of FRET followed by an abrupt decrease (Fig. 3D), indicating that the 5′ region of the displaced strand is brought close to the duplex end as DNA is unwound. This effect can arise from the enzyme maintaining contact with the 5′ region of the displaced strand or from the displaced strand becoming compact due to the flexibility of ssDNA. We prefer the former scenario because of its consistency with the larger FRET changes per step seen for PD2 than for PD1 (Fig. 1). A protein contact with the 5′ region of the displaced strand would lead to a looping of the strand, giving rise to larger distance change per step if the fluorophores are attached to the middle of the duplex (Fig. S7). In this view, the abrupt decrease in FRET may be attributed to NS3 losing its grip on the tracking strand and snapping or slipping back near the junction while maintaining contact with the 5′ region of the displaced strand.

Based on our findings, we propose the following model for NS3 unwinding of DNA (Fig. S9). Domains 1 and 2 of NS3 move along the tracking strand (3′ to 5′) one nucleotide at a time, consuming one ATP, where ATP binding and ADP release induces closing and opening of the two domains, respectively. The third domain of the protein lags behind by anchoring itself to the DNA until three such steps take place. At the third step, the spring-loaded domain 3 moves forward in a burst motion, unzipping three base pairs as a consequence. The displaced strand is likely to be sheltered by the enzyme instead of being released free. NS3 continues unwinding in three base pair steps up to about 18 bp unless it encounters an apparent barrier (movie S1). Unwinding performed with 24 or longer duplexes showed evidence of repetitive unwinding even when the duplex ends are not blocked (Fig. S8), suggesting that NS3 is not highly efficient in going much beyond 18 bp, which is consistent with the reported drop in processivity that is observed every 18 base-pairs in RNA unwinding in bulk solution (10).

The HCV genome is a ~10,000 nt ssRNA that is copied upon binding of the NS3/4A/5B replicative complex to highly structured terminal untranslated regions (UTRs). Sequence and structural analysis suggests that the UTRs are complex structures comprised of short stems and loops (23). The ability of NS3 to maintain contact with displaced strands may provide an advantage by allowing it to stay in a local region to keep RNA stems unwound, while reforming structure could hinder viral replication. The repetitive unwinding behavior of NS3 is reminiscent of the repeated translocation observed in Rep (24).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chirlmin Joo for help in manuscript preparation. Supported by NIHR01-GM060620 and R01-GM065367. T.H. and A.M.P. are investigators with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Materials and Methods

References and Notes

- 1.Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatology. 1997 Sep;26:34S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeff LB. Hepatology. 1998 Dec;28:1710. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavanchy D. J Hepatol. 1999;31(Suppl 1):146. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim DW, Gwack Y, Han JH, Choe J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995 Oct 4;215:160. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tai CL, Chi WK, Chen DS, Hwang LH. J Virol. 1996 Dec;70:8477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8477-8484.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang PS, Jankowsky E, Planet PJ, Pyle AM. Embo J. 2002 Mar 1;21:1168. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao HP, Xia DJ, Zhang LH, Liu KZ. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2002 Feb;31:2. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2002.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang LW, et al. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998 Jan 1;54:121. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997008883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JL, et al. Structure. 1998 Jan 15;6:89. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serebrov V, Pyle AM. Nature. 2004 Jul 22;430:476. doi: 10.1038/nature02704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumont S, et al. Nature. 2006 Jan 5;439:105. doi: 10.1038/nature04331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JY, Yang W. Cell. 2006 Dec 29;127:1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillingham MS, Wigley DB, Webb MR. Biochemistry. 2000 Jan 11;39:205. doi: 10.1021/bi992105o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali AJ, Lohman TM. Science. 1997;175:377. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 16.Kerssemakers JW, et al. Nature. 2006 Aug 10;442:709. doi: 10.1038/nature04928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joo C, et al. Cell. 2006 Aug 11;126:515. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin C, Kim JL. J Virol. 1999 Oct;73:8798. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8798-8807.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengoku T, Nureki O, Nakamura A, Kobayashi S, Yokoyama S. Cell. 2006 Apr 21;125:287. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen CB, et al. Science. 2006 Sep 29;313:1968. doi: 10.1126/science.1131981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marians KJ. Structure. 1997 Sep 15;5:1129. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korolev S, Yao N, Lohman TM, Weber PC, Waksman G. Protein Sci. 1998 Mar;7:605. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houghton M, Weiner A, Han J, Kuo G, Choo QL. Hepatology. 1991 Aug;14:381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myong S, Rasnik I, Joo C, Lohman TM, Ha T. Nature. 2005 Oct 27;437:1321. doi: 10.1038/nature04049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.