Abstract

Tris(phosphine)borane ligated Fe(I) centers featuring N2H4, NH3, NH2, and OH ligands are described. Conversion of Fe-NH2 to Fe-NH3+ by addition of acid, and subsequent reductive release of NH3 to generate Fe-N2, is demonstrated. This sequence models the final steps of proposed Fe-mediated nitrogen fixation pathways. The five-coordinate trigonal bipyramidal complexes described are unusual in that they adopt S = 3/2 ground states and are prepared from a four-coordinate, S = 3/2 trigonal pyramidal precursor.

Due the structural and mechanistic complexity of biological nitrogen fixation1 a variety of mechanisms have been proposed that invoke either Mo or Fe as the likely active site for N2 binding and reduction. Fe-NH2 is an intermediate common to both limiting mechanisms (i.e., distal vs. alternating) being considered for Fe-mediated N2 fixation scenarios at the FeMo-cofactor.2,3 Such a species could form via reductive protonation of the nitride intermediate of a distal scheme (i.e., Fe(N) → Fe(NH) → Fe(NH2) → Fe(NH3)), or by reductive protonation of a hydrazine intermediate of an alternating scheme (i.e., Fe(NH2-NH2) → Fe(NH2) + NH3). In the latter context, detection of an EPR active Fe-NH2 or possibly Fe-NH3 common intermediate has been proposed under reducing conditions at the FeMo-cofactor from substrates including N2, N2H4, and MeN=NH.3a

One key to realizing a catalytic cycle in either limiting scenario concerns the regeneration of Fe-N2 from Fe-NH2 with concurrent release of NH3.4 While there have been recent synthetic reports demonstrating NH3 generation from Fe(N) nitride model complexes, these studies have not provided information about the plausible downstream Fe(NHx) (X = 1, 2, 3) intermediates en route to NH3 release, nor have these systems illustrated the feasibility of regeneration of Fe-N2.5 Herein we describe a terminal, S = 3/2 Fe-NH2 complex for which the stepwise conversion to Fe-NH3, and then to Fe-N2 along with concomitant release of NH3, is demonstrated (eqns 1 and 2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

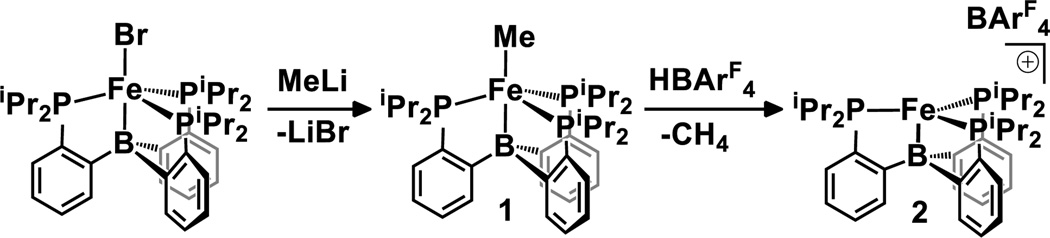

Addition of methyllithium to (TPB)FeBr6 affords the corresponding methyl complex (TPB)FeMe (1) in high yield (Scheme 1). Protonation of 1 by HBArF4·2Et2O (BArF4− = B(3,5-C6H3(CF3)2)4−) in a cold ethereal solution releases methane to yield [(TPB)Fe][BArF4] (2) which serves as a useful synthon with a vacant coordination site.

SCHEME 1.

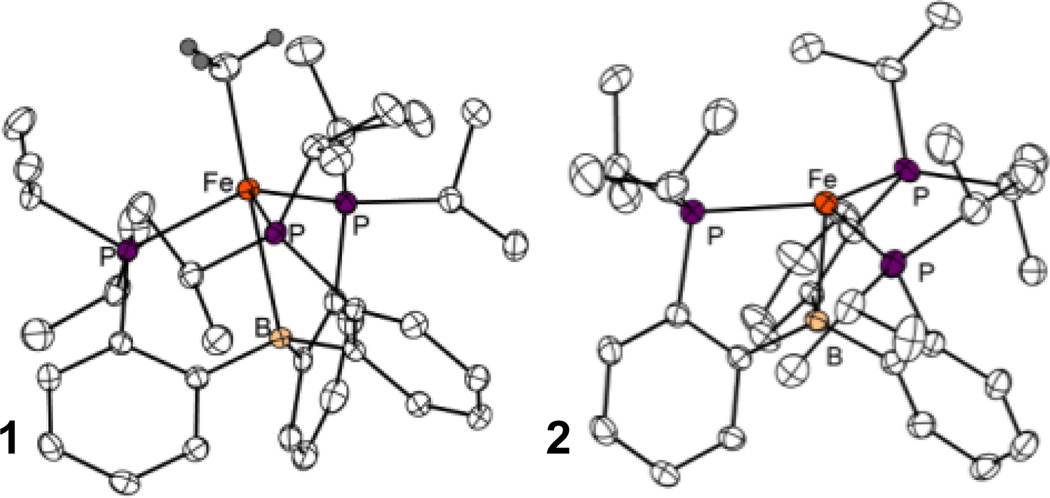

XRD data were obtained for 1 and 2 (Figure 1). The geometry of 1 is pseudo trigonal bipyramidal about Fe with an Fe-C bond length of 2.083(10) Å and an Fe-B bond length of 2.522 (2) Å. In the solid state 2 possesses a four-coordinate distorted trigonal pyramidal geometry with no close contacts in the apical site trans to boron, making this complex coordinatively unsaturated. Additionally, there is one wide P-Fe-P angle of 136°. The origin of this large angle is not clear, but a possible explanation is increased back-bonding from a relatively electron rich Fe center into the phosphine ligands that would arise from this distortion.

Figure 1.

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) structures of complexes 1 (A) and 2 (B) with hydrogen atoms and counterion (for B) omitted for clarity. See Table 1 for selected bond lengths and angles.

The Fe-B distance in 2 (2.217(2) Å) is markedly shorter than that in (TPB)FeBr (2.459(5) Å), which is noteworthy because one might expect the loss of an anionic σ-donor ligand to reduce the Lewis basicity of the metal and thus weaken the Fe-B bond. For example, the Au-B distance in (TPB)AuCl (2.318 Å) lengthens upon chloride abstraction to 2.448 Å in [(TPB)Au]+.7 To explain this difference we note that the boron center in four-coordinate 2 is less pyramidalized (Σ(C−B−C) = 347.3°) than that in five-coordinate (TPB)FeBr (Σ(C−B−C) = 341.2°), pointing to a weak interaction despite the short distance. These observations suggest that the geometry of 2 might be best understood as derived from a planar three-coordinate Fe(I) center distorted towards a T-shaped geometry,8 the unusually short Fe-B distance being due largely to the constraints imposed by the ligand cage structure. This interpretation is consistent with a computational model study: the DFT (B3LYP/6-31G(d)) optimized geometry of the hypothetical complex [(Me2PhP)3Fe]+ (see SI for details) exhibits a planar geometry with P-Fe-P angles of 134.8°, 113.1°, and 111.7°, very close to those measured for [(TPB)Fe]+ (137.5°, 113.2°, 109.1°).

When considering the bonding of the (Fe-B)7 subunit of 2 to estimate the best oxidation state and valence assignment, two limiting scenarios present themselves: Fe(III)/B(I) and Fe(I)/B(III). The structural data and computations for 2 are suggestive of a weak Fe-B interaction and indicate that this species is better regarded as Fe(I)/B(III) rather than Fe(III)/B(I). Calculations indicate that a small amount of spin density resides on the Batom of 2 (SI) and suggest some contribution from an Fe(II)/B(II) resonance form may also be relevant. The rest of the complexes 3–6 presented herein possess significantly longer, and presumably weaker, Fe-B interactions (vide infra) and are hence also better classified as Fe(I) species. Additional spectroscopic studies (e.g., XAS and Mössbauer) will help to better map the Fe-B bonding interaction across the variable Fe-B distances and also the spin states of the complexes. These studies would thereby help to determine the value and limitation of classically derived oxidation/valence assignments for boratranes of these types.9

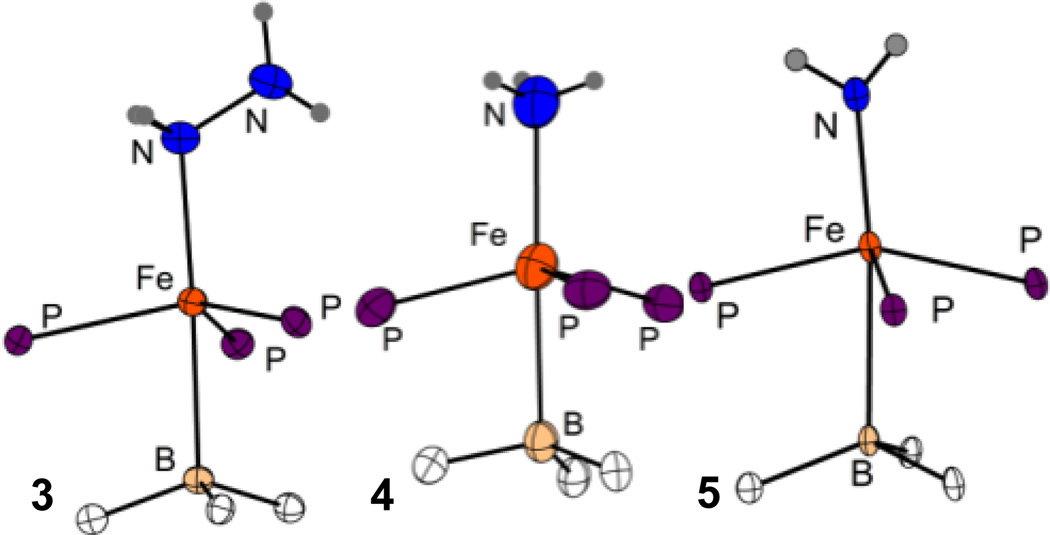

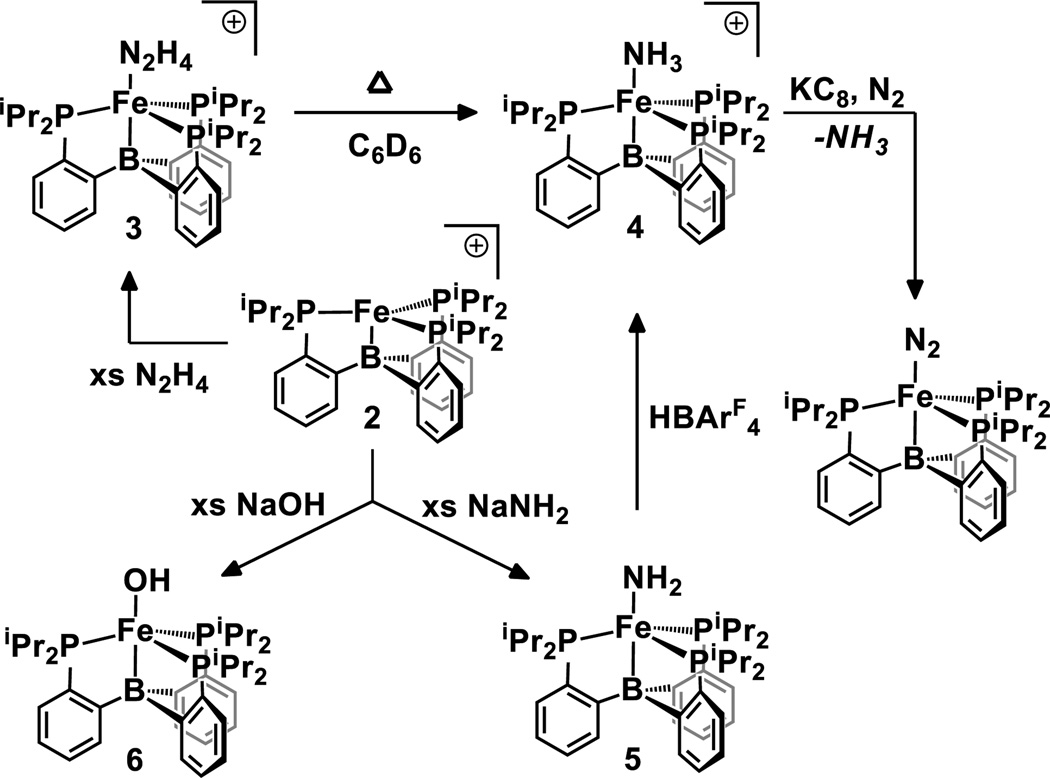

Solutions of 2 are orange in Et2O and pale yellow-green in THF. Titration of THF into an ethereal solution of 2 results in a distinct change in the UV-vis spectrum consistent with weak THF binding. Addition of an excess of N2H4 to an ethereal solution of 2 results in a slight lightening of the orange color of the solution to afford [(TPB)Fe(N2H4)][BArF4] (3) in 89% yield. Complex 3 shows a paramagnetically shifted 1H NMR spectrum indicative of an S = 3/2 Fe center that is corroborated by a room temperature solution magnetic moment, μeff, of 3.5 μB. Crystals of 3 were obtained and XRD analysis (Figure 2A) indicates a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry. The Fe-N distance of 2.205(2) Å is unusually long (2.14 Å is the average quaternary N-Fe distance in the Cambridge Structural Database) reflecting its unusual quartet spin state.

Figure 2.

XRD structures of the cores of complexes 3 (A), 4 (B), and 5 (C). See Table 1 for selected distances and angles.

Complex 3 is stable to vacuum, but solutions decompose cleanly at room temperature over hours to form the cationic ammonia complex [(TPB)Fe(NH3)][BArF4], 4, which was assigned by comparison of its 1H NMR spectrum with an independently prepared sample formed by the addition of NH3 to the cation 2. Analysis of additional degradation products shows only NH3 and trace H2 (SI). The assignment of 4 as an ammonia adduct was confirmed by XRD analysis (Figure 2B). Like 3, complex 4 shows a long Fe-N distance of 2.280(3) Å in the solid state. The complexes 2, 3 and 4 are unusual by virtue of their S = 3/2 spin states and underscore the utility of local 3-fold symmetry with respect to stabilizing high spin states at iron, even in the presence of strong-field phosphine ligands.

Addition of NaNH2 to the cation 2 affords the terminal amide, (TPB)Fe-NH2 (5) in ca. 85% non-isolated yield by 1H NMR integration. The XRD structure of 5 (Figure 2C) shows an overall geometry similar to that observed in 1, 3, and 4. Of interest is the short Fe-N distance of 1.918(3) Å by comparison to 4 (2.280(3) Å). The amide hydrogens were located in the difference map and indicate a nearly planar geometry about N (with the sum of the angles around N being 355°).

While the XRD data set of 5 is of high quality, we were concerned about the difficulty in distinguishing an Fe-NH2 group from a potentially disordered Fe-OH moiety. We therefore independently characterized the hydroxo complex, (TPB)Fe-OH (6) (Scheme 2), which possesses a geometry similar to that observed in 5 with an Fe-B distance of 2.4438(9) Å and an Fe-O distance of 1.8916(7) Å. Despite the structural similarity between 5 and 6, different spectral signatures in both their 1H NMR and EPR (Figure 3) spectra allow for facile distinction between them. Like 2, 3, and 4, both 5 and 6 are S = 3/2.

SCHEME 2.

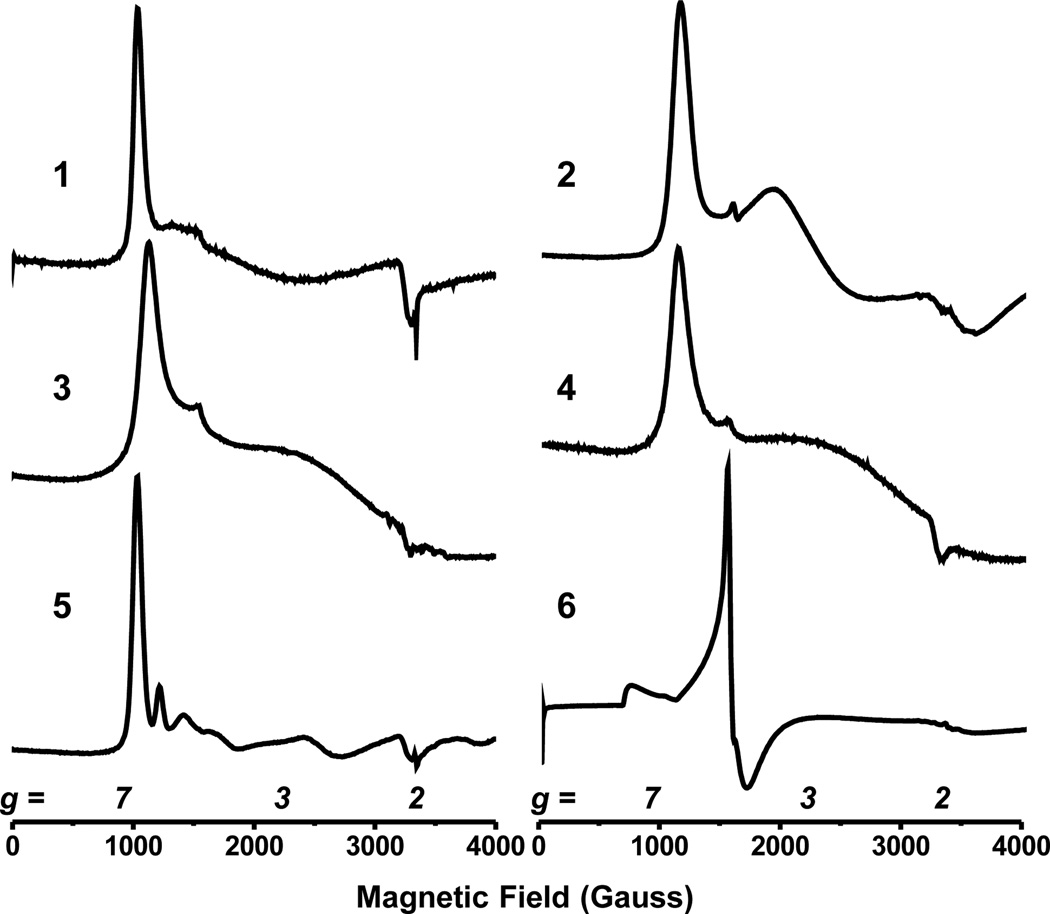

Figure 3.

X-Band EPR spectra for complexes 1–6. Conditions for 1: Toluene, 8 K; 2: 2:1 Toluene:Et2O, 10 K 3: 2-MeTHF, 10 K; 4: 2-MeTHF, 10 K; 5: 2-MeTHF, 10 K; 6: Toluene, 10 K.

Low-temperature EPR data (Figure 3) have been obtained on complexes 1–6. All complexes show features shifted to large g-values consistent with quartet Fe species.10 This assignment is verified by the solution magnetic moments obtained for these complexes. Variable temperature solid-state SQUID magnetic data for complexes 2–5 (SI) also establish quartet spin state assignments and display no evidence for spin-crossover phenomena. These data show a drop in magnetic moment in the range 50–70 K for all compounds studied. We propose that this effect is due to a large zero-field splitting in these species, which is consistent with Fe centers in related geometries.11 Simulations with zero-field splitting of 10–20 cm−1 provide reasonable fits to the data.

Parent amide complexes of first row transition metals are rare.12 Noteworthy precedent for related terminal M-NH2 species includes two square planar nickel complexes12a, d and one octahedral and diamagnetic iron complex, (dmpe)2Fe(H)NH2.12e In addition to their different coordination numbers, geometries, and spin-states, (dmpe)2Fe(H)(NH2) and 5 show a distinct difference at the Fe-NH2 subunit. Six-coordinate (dmpe)2Fe(H)(NH2) is an 18-electron species without π-donation from the amide ligand, which is pyramidalized as a result. By contrast, five-coordinate 5 accommodates π-bonding from the amide. This is borne out in its much shorter Fe-N distance (1.918(3) Å for 5 vs 2.068 Å for (dmpe)2Fe(H)(NH2)), and also its comparative planarity (the sum of the angles around N is 355° for 5 vs 325° for (dmpe)2Fe(H)(NH2)).

With the terminal amide 5 in hand we explored its suitability as a precursor to the previously reported N2 complex (TPB)Fe(N2) via release of NH3 and hence explored reduction/protonation vs protonation/reduction sequences as a means of effecting overall H-atom transfer to the Fe-NH2 unit. Attempts to carry out the one-electron reduction of 5 were not informative. For example, electrochemical studies of 5 in THF failed to show any reversible reduction waves, but the addition of harsh reductants (e.g., tBuLi) to 5 did show small amounts of (TPB)Fe(N2) in the product profile. A more tractable conversion sequence utilized protonation followed by chemical reduction. Thus, the addition of HBArF4·2Et2O to 5 at low temperature (−35 °C) rapidly generates the cationic ammonia adduct 4. The conversion is quantitative as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, and 4 can be isolated in ca. 90% yield from the solution. Subsequent exposure of 4 to one equiv of KC8 under an atmosphere of N2 releases NH3 and generates the (TPB)FeN2 complex in similarly high yield.

In summary, an unusual series of S = 3/2 iron complexes featuring terminally bonded N2H4, NH3, NH2, and OH functionalities has been thoroughly characterized. These complexes are supported by a tris(phosphine)borane ligand and are best described as Fe(I) species that feature weak Fe-B bonding, though other resonance contributions to the bonding scheme warrant additional consideration. The Fe-NH2 species faithfully models the reductive replacement of the terminal NH2 group by N2 with concomitant release of NH3, lending credence to such a pathway as mechanistically feasible in Fe-mediated N2 reduction schemes. Because spectroscopic detection of a common Fe-NH2 or Fe-NH3 intermediate under reductive turnover of the FeMo-cofactor has been recently proposed,3 EPR active model complexes of the types described here should prove useful for comparative purposes.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Selected Metrics for Complexes 1–6

| Fe-X (Å) | Fe-B (Å) | Avg. Fe-P (Å) |

Σ P-Fe-P |

Σ C-B-C |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.083(10) | 2.523(2) | 2.40 | 339° | 341° |

| 2 | - | 2.217(2) | 2.38 | 359° | 347° |

| 3 | 2.205(2) | 2.392(2) | 2.44 | 350° | 339° |

| 4 | 2.280(3) | 2.433(3) | 2.44 | 349° | 341° |

| 5 | 1.918(3) | 2.449(4) | 2.39 | 343° | 339° |

| 6 | 1.8916(7) | 2.4438(9) | 2.39 | 348° | 337° |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NIH (GM 070757) and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and through the NSF via a GRFP award to JSA. M.-E. M. acknowledges a Fellow-ship for Advanced Researchers from the Swiss National Science Foundation. Larry Henling and Dr. Jens Kaiser are thanked for their assistance with X-ray crystallography and Dr. Angelo DiBilio for his assistance with EPR measurements. We acknowledge the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Beckman Institute, and the Sanofi-Aventis BRP at Caltech for their generous support of the Molecular Observatory at Caltech. SSRL is operated for the DOE and supported by its Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NIH, NIGMS (including P41GM103393) and the NCRR (P41RR001209).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Detailed experimental and spectroscopic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Einsle O, Tezcan FA, Andrade SLA, Schmid B, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Science. 2002;297:1696–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.1073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spatzal T, Aksoyoglu M, Zhang LM, Andrade SLA, Schleicher E, Weber S, Rees DC, Einsle O. Science. 2011;334 doi: 10.1126/science.1214025. 940-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Crossland JL, Tyler DR. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;254:1883–1894. [Google Scholar]; (b) Field LD, Li HL, Dalgarno SJ, Turner P. Chem. Commun. 2008:1680–1682. doi: 10.1039/b802039f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hazari N. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:4044–4056. doi: 10.1039/b919680n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Vela J, Stoian S, Flaschenriem CJ, Münck E, Holland PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4522–4523. doi: 10.1021/ja049417l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Lukoyanov D, Dikanov SA, Yang Z-Y, Barney BM, Samoilova RI, Narasimhulu KV, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11655–11664. doi: 10.1021/ja2036018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:701–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y, Mankad NP, Peters JC. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:558–565. doi: 10.1038/nchem.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Betley TA, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6252–6254. doi: 10.1021/ja048713v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Scepaniak JJ, Fulton MD, Bontchev RP, Duesler EN, Kirk ML, Smith JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10515–10517. doi: 10.1021/ja8027372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Scepaniak JJ, Vogel CS, Khusniyarov MM, Heinemann FW, Meyer K, Smith JM. Science. 2011;331:1049–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.1198315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Scepaniak JJ, Young JA, Bontchev RP, Smith JM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3158–3160. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moret M-E, Peters JC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2063–2067. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sircoglou M, Bontemps S, Bouhadir G, Saffon N, Miqueu K, Gu W, Mercy M, Chen C-H, Foxman BM, Maron L, Ozerov OV, Bourissou D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16729–16738. doi: 10.1021/ja8070072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A stable T-shaped,three-coordinate Fe(I) is known: Ingleson MJ, Fullmer BC, Buschhorn DT, Fan H, Pink M, Huffman JC, Caulton KG. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:407–409. doi: 10.1021/ic7023764.

- 9.(a) Amgoune A, Bourissou D. Chem. Comm. 2011;47:859–871. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04109b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hill AF, Owen GR, White AJP, Williams DJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:2759–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pang K, Quan SM, Parkin G. Chem. Comm. 2006:5015–5017. doi: 10.1039/b611654j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoian SA, Yu Y, Smith JM, Holland PL, Bominaar EL, Munck E. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:4915–4922. doi: 10.1021/ic050321h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harman WH, Harris TD, Freedman DE, Fong H, Chang A, Rinehart JD, Ozarowski A, Sougrati MT, Grandjean F, Long GJ, Long JR, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:18115–18126. doi: 10.1021/ja105291x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Adhikari D, Mossin S, Basuli F, Dible BR, Chipara M, Fan H, Huffman JC, Meyer K, Mindiola DJ. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:10479–10490. doi: 10.1021/ic801137p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brady E, Telford JR, Mitchell G, Lukens W. Acta Cryst. C. 1995;51:558–560. [Google Scholar]; (c) Redshaw C, Wilkinson G, Hussain-Bates B, Hursthouse MB. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton. 1992:1803–1811. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cámpora J, Palma P, del Río D, Conejo MM, Álvarez E. Organometallics. 2004;23:5653–5655. [Google Scholar]; (e) Fox DJ, Bergman RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8984–8985. doi: 10.1021/ja035707a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sofield CD, Walter MD, Andersen RA. Acta Cryst. C. 2004;60:465–466. doi: 10.1107/S0108270104018840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.