Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the distribution and clinical impact of glycogen accumulation on heart structure and function in individuals with GSD III.

Methods: We examined cardiac tissue and the clinical records of three individuals with GSD IIIa who died or underwent cardiac transplantation. Of the two patients that died, one was from infection and the other was from sudden cardiac death. The third patient required cardiac transplantation for end-stage heart failure with severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Results: Macro- and microscopic examination revealed cardiac fibrosis (n = 1), moderate to severe vacuolation of cardiac myocytes (n = 3), mild to severe glycogen accumulation in the atrioventricular (AV) node (n = 3), and glycogen accumulation in smooth muscle cells of intramyocardial arteries associated with smooth muscle hyperplasia and profoundly thickened vascular walls (n = 1).

Conclusion: Our findings document diffuse though variable involvement of cardiac structures in GSD III patients. Furthermore, our results also show a potential for serious arrhythmia and symptomatic heart failure in some GSD III patients, and this should be considered when managing this patient population.

Introduction

Cardiac involvement is a well-known feature in several glycogen storage diseases (GSDs) such as types II, III, IV, and IX and PRKAG2, a gene that encodes the regulatory γ2-subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which, when mutated, causes glycogen storage cardiomyopathy. Significant cardiac involvement is well recognized in Pompe disease (GSD II) with marked glycogen accumulation affecting both the structure and the function of the heart (Gillette et al. 1974; Seifert et al. 1992; Ansong et al. 2006). While cardiomyopathy has been a known potential complication in some individuals with GSD III, the full extent of cardiac disease, especially in adults, is not well understood.

GSD III is a rare disease of variable clinical severity affecting primarily the liver, skeletal muscle, and heart (Chen et al. 2009). It is caused by deficient activity of glycogen debranching enzyme, which is a key enzyme in glycogen degradation. Unlike some of the GSDs, glycogen accumulation in GSD III is structurally abnormal with branched outer points called limit dextrin. This abnormal glycogen product is thought to cause liver fibrosis/cirrhosis (Coleman et al. 1992; Portmann et al. 2007). There are two subtypes of GSD III: subtype a (GSD IIIa) that affects muscle and liver and subtype b (GSD IIIb) that affects only liver. The diagnosis of GSD III is made based on clinical features including hepatomegaly, fasting ketotic hypoglycemia without lactic acidosis, elevated transaminases, and creatine kinase (CK) levels as well as by measuring debranching enzyme activity in muscle and liver biopsy specimens. The diagnosis is confirmed by genetic testing for mutations in the AGL gene, the only gene known to be associated with GSD III. Currently, treatment for GSD III is limited to dietary management, including frequent feeds and/or cornstarch to ensure euglycemia. A high-protein diet is thought to possibly improve muscular and cardiac manifestations (Slonim et al. 1982; Slonim et al. 1984; Dagli et al. 2009), although more evidence is needed to confirm this finding.

Cardiac involvement in GSD III is variable but is typically manifested as left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) that may progress to symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Carvalho et al. 1993; Talente et al. 1994; Lee et al. 1995; Akazawa et al. 1997). Life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias have been reported in rare instances (Miller et al. 1972; Moses et al. 1989; Tada et al. 1995). There are also a few cases in which cardiac symptoms progressed and culminated in sudden death (Miller et al. 1972) or required cardiac transplantation (Cochrane et al. 2007).

Our group recently reported on cardiac wall thickness and left ventricular mass, as measured by echocardiography, over time in individuals with GSD III (Vertilus et al. 2010). To further our understanding of the impact of glycogen accumulation on heart structure and function in GSD III, we examined cardiac tissue of three individuals with GSD IIIa: one patient following cardiac transplantation and two patients following death (one with Aspergillus fumigatus and Pneumocystis jiroveci infection and one with sudden cardiac death).

Methods

Three individuals with GSD III that had heart tissue available to study were identified; these individuals had consented to a Duke University Medical Center IRB-approved study of the natural history of GSD III. Following death or cardiac transplantation, cardiac tissue was collected by an anatomical pathologist or a local transplant team. After customary clinical pathology review, slides (patients 1 and 2) or cardiac tissue (patient 3) were shipped to Duke University Medical Center for review by a Duke pathologist. Only slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin were reviewed since glycogen accumulation within muscle cells results in a characteristic vacuolar myopathy (Yanovitch et al. 2010). Corresponding medical records, including autopsy reports if available, were reviewed for pertinent clinical information.

Results

Patient 1 was diagnosed with GSD III at age 1 1/2 years. Mutation analysis of the AGL gene detected an intron 18 mutation, predicted to be pathological, and a mutation, c.118C>T, in exon 4 that created a truncated protein, p.Gln40X. The patient had a long-standing history of progressive fatigue, which worsened over the years. She was active in childhood but would require frequent rest periods; however, in her mid-20s, she had activity limiting fatigue and began having exercise-induced muscle cramping. She had a complex disease course with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis, which necessitated an orthotopic liver transplant at age 24 years. Pretransplant cardiac workup was unremarkable with a normal echocardiogram and ECG. CK levels obtained pre-liver transplant were 1,124 ng/mL (normal range 30–220 ng/mL) with a creatine kinase-MB fraction (CK-MB) of 21 ng/mL (normal range 0–8 ng/mL). Troponin levels are not known. Posttransplant, her CK was 84 ng/mL with a CK-MB of 8 ng/mL. The patient received standard immunosuppression as part of her posttransplant care. She developed steroid-resistant rejection requiring thymoglobulin. As a result of her immunosuppression, she developed A. fumigatus infection of the brain and heart and P. jiroveci pneumonia with dissemination to the bone marrow. She died at age 27 years as a complication of these infections.

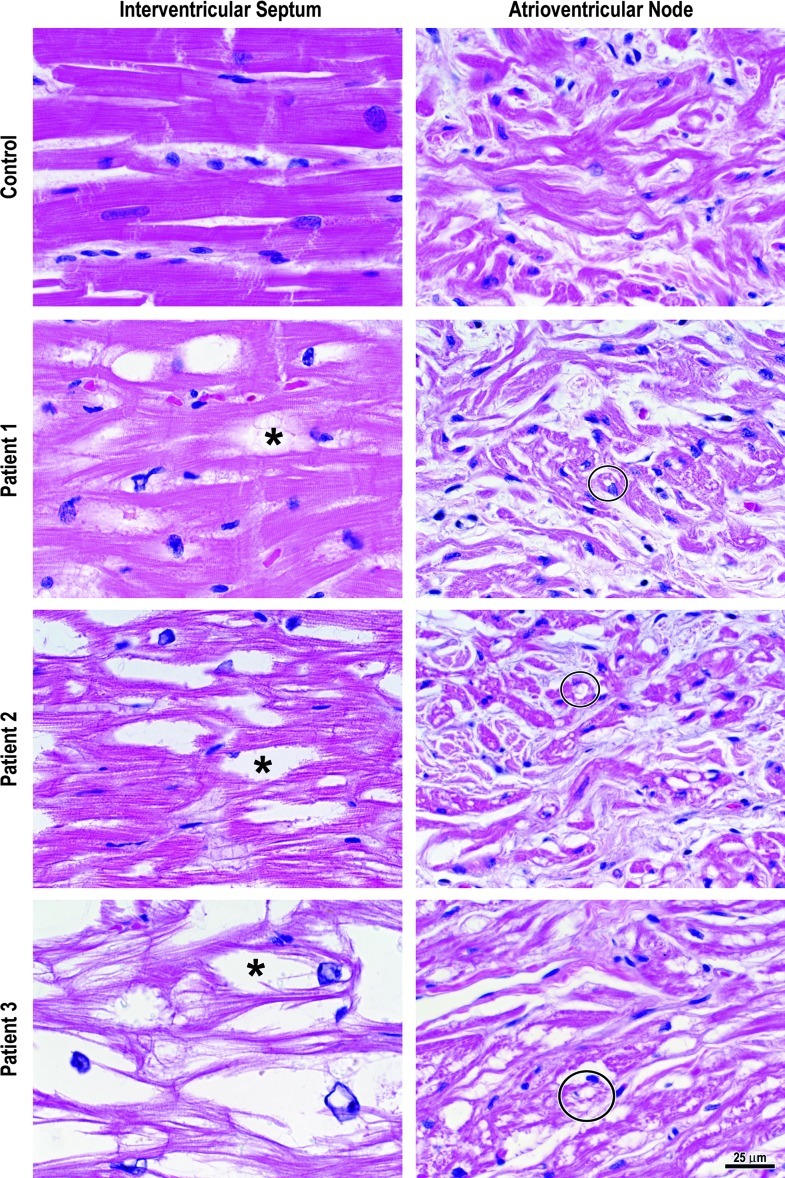

Postmortem examination of the heart revealed mild cardiomegaly with a heart weight of 350 gm (normal mean ± 1 S.D. = 281 ± 30 gm) and a left ventricular wall thickness of 2.0 cm (normal ≤ 1.5 cm). The right ventricular wall thickness was normal. No atherosclerosis was grossly discernible in the coronary arteries. Microscopic examination revealed moderate vacuolation of right and left ventricular and right atrial cardiac myocytes due to cytosolic glycogen accumulation, mild to moderate glycogen-induced vacuolation of the specialized myocytes of the sinoatrial (SA) node, and mild vacuolation of the atrioventricular (AV) node myocytes (Fig. 1). Intramyocardial arteries did not exhibit vacuolation or hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells. However, the SA node artery had mild vacuolation and moderate hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells, and the AV node artery had mild vacuolation and mild hyperplasia of its smooth muscle. No fibrosis was evident.

Fig. 1.

Cardiac and AV node myocytes from a 22-year-old man with a normal heart (control) were without vacuolation. All three patients with GSD III exhibited some degree of vacuolation of cardiac myocytes (asterisk) due to glycogen accumulation and glycogen-induced vacuolation of the specialized myocytes of the atrioventricular node (circles)

Patient 2 was diagnosed with GSD III at age 8 months when she presented with hepatomegaly and hypoglycemia. Sequence analysis of the AGL gene disclosed a homozygous exon 31 deletion. She had persistent poor growth throughout childhood despite optimization of nutrition, though she was otherwise healthy during this time period. At 10 years old, she was diagnosed with a myopathy secondary to GSD III. Her CK was consistently elevated ranging from 200 to 680 ng/mL (normal 30–220 ng/mL). Her CK-MB fraction was only mildly elevated with a range of 6–31 ng/mL (normal 0–8 ng/mL), which would not suggest a primary cardiac source given its proportion of total CK. Troponin levels were not obtained. The patient did complain of easy fatigability that was slowly progressive over the years but did not endorse myalgias. At age 25, a screening cardiology evaluation, including echocardiogram and 24-h Holter monitor, was normal. Serial echocardiograms and EKGs were normal though she did have a history of recurrent atypical chest pain of unclear etiology. One month prior to her death, a cardiologist investigated her atypical chest pain; cardiac testing included stress echocardiogram and electrocardiogram. Mild LVH was noted on stress echocardiogram; the electrocardiogram was normal.

At age 33, the patient began having nocturnal seizure-like activity that spontaneously terminated. All seizure-like activity occurred while she was asleep. Her seizures were not associated with documented hypoglycemia; she never had a history of status epilepticus or daytime seizures, and she was on antiepileptic medication. Multiple attempts to obtain a brain MRI or EEG were unsuccessful due to patient noncompliance with appointments. Despite multiple emergency room visits for seizure-like activity, the patient never had a seizure witnessed by anyone except her boyfriend.

Patient 2 died unexpectedly at age 36 years. Postmortem evaluation of the brain, including periodic acid Schiff staining, was reported as showing no focal lesions or significant abnormalities. Blood toxicology screen was negative.

Postmortem cardiac examination indicated a heart weight within the normal range but concentric LVH with a wall thickness of 2.0 cm. Coronary arteries were free of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. The myocardium had no evidence of acute infarction, scarring, or fibrosis. Cardiac myocytes exhibited moderate to severe vacuolar myopathy. The SA node had moderate to severe vacuolar myopathy, while the AV node and the penetrating bundle of His exhibited moderate vacuolation. The glycogen accumulation in the conduction system was similar to that seen in Pompe disease (Bharati et al. 1982) and was felt to be significant enough to predispose the patient to a lethal arrhythmia. Intramyocardial arteries did not exhibit vacuolation or hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells. Both the SA node and AV node arteries had mild vacuolation of smooth muscle cells, but only the AV node artery had mild hyperplasia of the smooth muscle cells. No fibrosis was evident.

Patient 3 was diagnosed with GSD III at age 6 months by enzymology after open liver biopsy. Molecular analysis of the AGL gene documented an exon 23 frameshift mutation, c.3014delG, that lead to a premature protein truncation, p.Cys1005PhefsStop7, and an exon 34 missense mutation, c.4543T>C, that lead to an amino acid substitution that was predicted to be damaging, p.Cys1515Arg. Patient 3 had rapid progression of cirrhosis with portal hypertension and bleeding varices, and at age 5 1/2, she underwent orthotopic liver transplantation. She then developed a progressive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with systolic heart failure; therefore, a cardiac defibrillator was inserted at age 23 years. Despite medical management, her heart failure became more symptomatic with severe dyspnea on exertion, worsening fatigue, 3-pillow orthopnea, and chest tightness with slight exertion. CK and troponin levels were consistently elevated with a range of 2,773–8,623 ng/mL and 0.07 ng/mL, respectively, and cardiac CK-MB documented at an increased level of 66 ng/mL. Cardiac imaging demonstrated an ejection fraction of 20–40% with severe concentric LVH and asymmetric septal hypertrophy. Given her worsening cardiac function and symptomatic heart failure, she underwent heart transplantation at age 27 years.

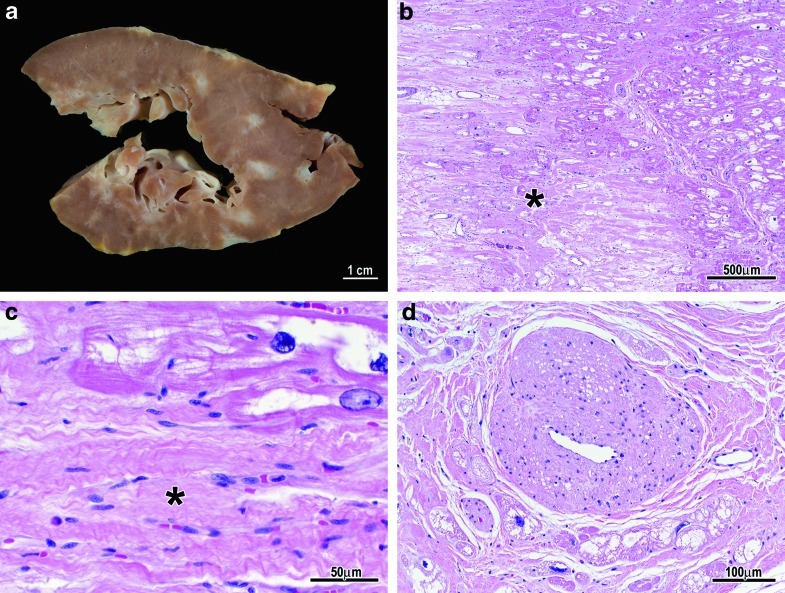

Examination of the explanted heart indicated severe left and right ventricular hypertrophy (left ventricular wall thickness = 2.3 cm; right ventricular wall thickness = 0.9 cm, normal ≤ 0.5 cm), numerous foci of myocardial scarring throughout the left and right ventricles (Fig. 2a–c), and subendocardial fibrosis (Fig. 2a). Microscopic examination confirmed the fibrosis (Fig. 2b, c) and severe vacuolation of right and left ventricular cardiac myocytes (Fig. 1) and the specialized myocytes of the AV node (Fig. 1). The SA node was not available for study. The right, left main, left anterior descending, and left circumflex coronary arteries were without atherosclerosis, while intramyocardial small arteries had moderate vacuolation of smooth muscle cells and severe smooth muscle cell hyperplasia resulting in markedly thickened walls and luminal stenosis (Fig. 2d). The AV node artery had mild vacuolation of smooth muscle cells but no smooth muscle hyperplasia.

Fig. 2.

(a) Gross photo of scarring/fibrosis (white areas) in patient 3. (b/c) Photomicrographs showing dense fibrosis replacing myocytes (asterisk). (d) Fibromuscular hyperplasia of a small intramyocardial artery with marked luminal stenosis

The cardiac pathology findings of our three patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of cardiac pathology

| Patient | Myocardium | Conduction system | Intramyocardial arteries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomegaly | LVH | RVH | Vacuolation of myocytes | Fibrosis | Glycogen accumulation in SA node | Glycogen accumulation in AV node | Glycogen accumulation in bundle of His | Glycogen accumulation in smooth muscle cells | Smooth muscle hyperplasia | |

| 1 | + | + | 0 | ++ | 0 | + to ++ | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | + | 0 | ++ to +++ | 0 | ++ to +++ | ++ | ++ | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | N/A | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, RVH right ventricular hypertrophy, N/A no histological sections available for review

0 none, + mild, ++ moderate, +++ severe

Discussion

Cardiac involvement for individuals with GSD III typically presents with asymptomatic LVH. The LVH has been reported to progress to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Carvalho et al. 1993; Talente et al. 1994; Lee et al. 1995; Akazawa et al. 1997); however, the cardiac involvement and progression of the disease are variable. There is not a reliable method available to predict which patient will have cardiac involvement or progress to cardiomyopathy. It is possible to consider genotype/phenotype correlation, but, as seen in our case series, the patients do not share mutations in the same exons or similar mutation types. Molecular information was not available in other reported cases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Literature review of cardiac cases with pathology findings in GSD III

| Reference | Patients | Ages (years)/sex | Cardiac symptoms/resolution | Clinical cardiac findings | Pathology cardiac findings | Liver/muscle involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al. (1972) | 1 | 3 months/female | Sudden death at 3 months | ECG – short PR interval and biventricular hypertrophy with right ventricular dominance | Autopsy – enlarged heart with myocardial thickening with narrow ventricular cavities, gray-red coloring with glassy appearance | Severe hypoglycemia, enlarged liver |

| Olson et al. (1984) | 1 | 25/female | Orthopnea due to pulmonary edema during pregnancy | Echo – marked thickening of the ventricular myocardium, normal systolic function | Endomyocardial biopsy – increased intracellular glycogen, no appreciable myofiber or myofibrillar disarray | Not mentioned |

| Tada et al. (1995) | 1 | 23/male | Malaise, heart palpitations; fitted with a cardiac defibrillator | ECG – ventricular tachycardia Echo – LV dilation and LV concentric hypertrophy; LV wall thinning and brighter indicating fibrosis, abnormal systolic function (SF9%) | Endomyocardial biopsy – increased intracellular glycogen, no myofiber or myofibrillar disarray | Increased CK levels (1516 U/L) |

| Akazawa et al. (1997) | 1 | 38/female | Fatigue, dyspnea on exertion; sudden death | ECG – LV hypertrophy, pathological Q waves, and inverted T waves in leads I, II, aVL, and V3 6 Echo – kinetic and thin portions of the LV wall, abnormal systolic function (SF24%), LVH present (LV mass 225 gm/m2 and septum 18 mm) |

Endomyocardial biopsy – vacuolation of myocytes Autopsy – moderate LV hypertrophy, scattered and patchy fibrosis, focal fibrosis distributed throughout the myocardium | Persistent elevation of CK |

| Moon et al. (2003) | 1 | 32/male | Exertional chest pain | Myocardial fibrosis on cMR | Not done | Not mentioned |

| Ingle et al. (2004) | 1 | 21/male | Dyspnea on exertion and chest pain; diagnosed on autopsy | ECG – biventricular hypertrophy Echo – hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy |

Autopsy – massively enlarged, globular, congested heart with marked right and left ventricular hypertrophy, marked vacuolation of myocytes | Hepatic cirrhosis and hepatocellular failure with portal hypertension |

Echo echocardiography, LV left ventricle, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, CK creatine kinase

As patients with GSD III have an increased survival, long-term cardiac complications are being increasingly recognized. The prevalence of symptomatic cardiac involvement is not yet known but case reports and case series suggest that the symptoms can be indicative of life-threatening cardiac events in some patients (Miller et al. 1972; Akazawa et al. 1997; Ingle et al. 2004; Vertilus et al. 2010). Furthermore, a patient’s disease may progress to the extent that he/she may require cardiac transplantation as was seen in one of the reported patients (Cochrane et al. 2007). In our case series, we have documented abnormalities of the myocardium, conduction system, and intramyocardial arteries. Given our cases and those in the literature, it is evident that cardiac findings in GSD III are not only variable in terms of severity but also variable in the extent of cardiac structures involved, the age of presentation, and rate of progression.

Glycogen accumulation in the conduction system was present in all three of our patients ranging from mild to severe glycogen accumulation in the AV node. Tada et al. presented a case of a 23-year-old man with GSD III who had sudden palpitation and was subsequently diagnosed with a sustained recurrent ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Tada et al. 1995). The patient underwent implantation of an automatic defibrillator. The mechanism of the VT was determined to be reentry which is often caused by myocardial fibrosis or fatty infiltration as a result of infarction or cardiomyopathy. Myocardial fibrosis is thought to possibly cause spatial dispersion of the cardiac impulse supporting reentrant arrhythmias (Dritsas et al. 1992; Yi et al. 1998; Shirani et al. 2000; McDowell et al. 2008). Tada et al. speculated that the glycogen accumulation in the heart may have led to a ventricular conduction delay which drove the reentrant circuit and thereby caused the VT. Patient 3 in our case series had striking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and myocardial fibrosis on pathological examination. Prior to cardiac transplant, patient 3 had an ejection fraction of 20–40% with severe concentric LVH and asymmetric septal hypertrophy with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and QRS widening which necessitated defibrillator placement. On pathological examination of her heart, significant fibrosis was noted. It is possible that the fibrosis caused an arrhythmia that required a defibrillator. The moderate glycogen accumulation in the conduction system of patient 2 also provides a possible explanation for her sudden death. It may be that the glycogen in the conduction system served as a substrate for a lethal arrhythmia.

The glycogen accumulation in the conduction system in individuals with GSD III and related arrhythmias is similar to reports of individuals with Pompe disease (Bharati et al. 1982), Danon disease (Arad et al. 2005), and individuals with mutations in PRKAG2 (Arad et al. 2002), a condition of cardiomyopathy and progressive degenerative conduction system disease due to storage of amylopectin, a glycogen-related substance. Individuals with Pompe disease have conduction abnormalities due to glycogen accumulation, including a shortened PR interval, an increased QT dispersion, and large left ventricular voltages on ECG (Bharati et al. 1982). This finding is similar to PRKAG2 where individuals have ventricular hypertrophy, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, and progressive conduction system disease. In these cases, it has been suggested that disruption of the annulus fibrosis by glycogen filled myocytes causes preexcitation (Arad et al. 2003). The findings of fibrosis and arrhythmias in individuals with other disorders of abnormal glycogen storage underscore the importance of further research to understand the cardiac pathology in GSD III to help predict which patients could be at risk for sudden cardiac events.

Cardiac fibrosis in individuals with GSD III is an underrecognized finding without clear clinical significance or etiology (Tada et al. 1995; Akazawa et al. 1997; Moon et al. 2003). In the liver, the glycogen accumulates as limit dextrin, an abnormal form of short-branched glycogen (Chen et al. 2009). It is thought that the accumulation of abnormal glycogen results in hepatocellular damage with subsequent fibrosis after hepatocytes die (Coleman et al. 1992). It is not unreasonable to consider the possibility that abnormal glycogen accumulation in the heart may cause similar cardiac fibrosis. However, the only patient in our series with cardiac fibrosis had markedly stenotic intramyocardial arteries, thus raising the possibility that the fibrosis resulted from ischemic death of myocytes. Study of additional subjects with GSD III and cardiac fibrosis will help clarify the cause of cardiac fibrosis.

The long-term impact of the fibrosis and appropriate monitoring are unknown. The role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMR) is unclear, but given the cardiac fibrosis documented here and in other studies (Tada et al. 1995; Akazawa et al. 1997; Moon et al. 2003), cMR may serve as a screening tool for patients with chest pain or other cardiac symptoms (Vertilus et al. 2010). cMR has been used to characterize other storage disorders including Pompe disease where one of the arguments for its use is the ability of cMR to detect myocardial fibrosis (Barker et al. 2010).

Surveillance for cardiac manifestations in individuals with GSD III was recently defined by a group of experts (Kishnani et al. 2010). It is possible that cMR will provide additional information regarding the extent of cardiac fibrosis for individuals with GSD III and indicate those that are at higher risk for life threatening arrhythmias. More long-term research is needed to evaluate the clinical utility of cMR in GSD III. Lessons learned from carefully studying these individuals and obtaining a detailed cardiac history will lead to better understanding of the cardiac manifestations of this disease and guide physicians in better clinical management for this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by The Association of Glycogen Storage Disease, USA, as well as the National Institutes of Health through the Duke Clinical Research Center. This publication was made possible, in part, by grant number 5UL1RR024128-03 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information of reengineering the clinical research enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp/. We would like to thank the patients with GSD III and their families that contributed to this research. We would also like to thank Ms. Susan Reeves who assisted with the preparation of the figures and Drs. Heather Ross, Stephen Waller, Melissa Jacobs, Ivan Damjanov, and Sam Simmons who assisted in the collection of the tissue.

A portion of the results submitted in this manuscript was presented by Stephanie Austin at the 2010 American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting in Washington, DC.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Article Note

This chapter documents diffuse though variable involvement of cardiac structures in GSD III patients and demonstrates the potential for serious arrhythmia and symptomatic heart failure in some GSD III patients.

References

- Akazawa H, Kuroda T, et al. Specific heart muscle disease associated with glycogen storage disease type III: clinical similarity to the dilated phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(3):532–533. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansong AK, Li JS, et al. Electrocardiographic response to enzyme replacement therapy for Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2006;8(5):297–301. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000195896.04069.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arad M, Benson DW, et al. Constitutively active AMP kinase mutations cause glycogen storage disease mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(3):357–362. doi: 10.1172/JCI14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arad M, Moskowitz IP, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing mutant PRKAG2 define the cause of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in glycogen storage cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;107(22):2850–2856. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000075270.13497.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arad M, Maron BJ, et al. Glycogen storage diseases presenting as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(4):362–372. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PC, Pasquali SK, et al. Use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate cardiac structure, function and fibrosis in children with infantile Pompe disease on enzyme replacement therapy. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;101(4):332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharati S, Serratto M, et al. The conduction system in Pompe’s disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 1982;2(1):25–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02265613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho JS, Matthews EE, et al. Cardiomyopathy of glycogen storage disease type III. Heart Vessels. 1993;8(3):155–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01744800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YT, Kishnani PS, et al. et al. Glycogen storage diseases. In: Valle D, Beaudet A, Vogelstein B, et al.et al., editors. Scriver’s online metabolic & molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane AB, Fedson SE, et al. Nesiritide as bridge to multi-organ transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(1):308–310. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA, Winter HS, et al. Glycogen debranching enzyme deficiency: long-term study of serum enzyme activities and clinical features. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15(6):869–881. doi: 10.1007/BF01800225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagli AI, Zori RT et al (2009) Reversal of glycogen storage disease type IIIa-related cardiomyopathy with modification of diet. J Inherit Metab Dis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dritsas A, Sbarouni E, et al. QT-interval abnormalities in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15(10):739–742. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960151010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette PC, Nihill MR, et al. Electrophysiological mechanism of the short PR interval in Pompe disease. Am J Dis Child. 1974;128(5):622–626. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1974.02110300032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingle SA, Moulick ND, et al. Hepatocellular failure in glycogen storage disorder type 3. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:158–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishnani PS, Austin SL, et al. Glycogen storage disease type III diagnosis and management guidelines. Genet Med. 2010;12(7):446–463. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e655b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Burch M, et al. Plasma creatine kinase and cardiomyopathy in glycogen storage disease type III. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1995;18(6):751–752. doi: 10.1007/BF02436768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell R, Li JS, et al. Arrhythmias in patients receiving enzyme replacement therapy for infantile Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2008;10(10):758–762. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318183722f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CG, Alleyne GA, et al. Gross cardiac involvement in glycogen storage disease type 3. Br Heart J. 1972;34(8):862–864. doi: 10.1136/hrt.34.8.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon JC, Mundy HR, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Myocardial fibrosis in glycogen storage disease type III. Circulation. 2003;107(7):e47. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000050691.73932.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses SW, Wanderman KL, et al. Cardiac involvement in glycogen storage disease type III. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;148(8):764–766. doi: 10.1007/BF00443106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LJ, Reeder GS, et al. Cardiac involvement in glycogen storage disease III: morphologic and biochemical characterization with endomyocardial biopsy. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(7):980–981. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portmann B, Thompson R, et al., editors. Genetic and metabolic liver disease. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert BL, Snyder MS, et al. Development of obstruction to ventricular outflow and impairment of inflow in glycogen storage disease of the heart: serial echocardiographic studies from birth to death at 6 months. Am Heart J. 1992;123(1):239–242. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90779-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirani J, Pick R, et al. Morphology and significance of the left ventricular collagen network in young patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slonim AE, Weisberg C, et al. Reversal of debrancher deficiency myopathy by the use of high-protein nutrition. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(4):420–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slonim AE, Coleman RA, et al. Myopathy and growth failure in debrancher enzyme deficiency: improvement with high-protein nocturnal enteral therapy. J Pediatr. 1984;105(6):906–911. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(84)80075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada H, Kurita T, et al. Glycogen storage disease type III associated with ventricular tachycardia. Am Heart J. 1995;130(4):911–912. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talente GM, Coleman RA, et al. Glycogen storage disease in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(3):218–226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-3-199402010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertilus SM, Austin SL, et al. Echocardiographic manifestations of Glycogen Storage Disease III: increase in wall thickness and left ventricular mass over time. Genet Med. 2010;12(7):413–423. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e0e979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitch TL, Banugaria SG, et al. Clinical and histologic ocular findings in Pompe disease. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47(1):34–40. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20100106-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi G, Elliott P, et al. QT dispersion and risk factors for sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(12):1514–1519. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00696-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]