Abstract

This study describes a cblE type of homocystinuria associated with haemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) features. We report on a male infant aged 43 days presenting with failure to thrive, hypotonia, pancytopaenia, HUS symptoms (microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopaenia with signs of renal involvement) and fatal evolution. An underlying cobalamin disorder was diagnosed after a bone marrow examination revealed megaloblastic changes associated with hyperhomocysteinaemia. An urinary organic acid analysis revealed normal methylmalonic acid excretion. The cblE diagnosis was confirmed with a complementation analysis using skin fibroblasts and genetic studies of the MTRR gene. The patient treatment included parenteral hydroxocobalamin, carnitine, betaine and folinic acid, but there was no response. After the autopsy, the histopathological examination of the kidneys showed marked myointimal proliferation and narrowing of the vascular lumen. The central nervous system showed signs of haemorrhage that affected the putamen and the thalamus; diffuse white matter lesions with spongiosis, necrosis and severe astrogliosis were also observed. Microangiopathy was observed with an increase in vessel wall thickness, a reduction of the arterial inner diameter and capillary oedema. The signs of necrosis and haemorrhage were detected in the cerebellum, the cerebellar peduncles, the tegmentum and the bulbar olives.

In conclusion, cblE should be considered when diagnosing patients presenting with HUS signs and symptoms during the newborn period. Despite early diagnosis, however, the specific treatment measures were not effective in this patient.

Introduction

The cblE type of homocystinuria (OMIM236270) is a rare condition that is related to cobalamin metabolism, affects the 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase gene (MTRR, MIM 602568) and causes isolated hyperhomocysteinaemia (Wilson et al. 1999). To date, approximately 20 patients have been reported; therefore, the clinical spectrum of the disease must still be defined. The clinical hallmarks for the condition are megaloblastic anaemia, developmental delay, feeding difficulties and cerebral atrophy (Skovby et al. 2003). The presentation and diagnosis of cblE typically occurs in childhood, although manifestations in adulthood or in the first months of life have been reported (Müller et al. 2007; Zavadakova et al. 2002; Vilaseca et al. 2003). Vascular system involvement in these patients has been suggested (Zavadakova et al. 2002), although to our knowledge such findings have not been reported.

Published studies of the genetic causes of haemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (Noris et al. 2005) have investigated issues such as complement component deficiencies (particularly the C3 fraction deficiency), deficiency of the complement regulatory protein in the alternative complement pathway (CD 46, factor I and factor H) (Zimmerhackl et al. 2006), and the cblC defect (Chenel et al. 1993; Geraghty et al. 1992; Kind et al. 2002; Russo et al. 1992). Additionally, only one case has reported an association between the cblG defect, HUS and pulmonary hypertension (Labrune et al., 1999). We believe that the association between the cblE type of homocystinuria and HUS has not been reported previously.

This paper reports on a new case of the cblE defect that presented after the newborn period with severe vascular involvement, as demonstrated by histopathological studies, HUS features and fatal evolution despite early treatment.

Material and Methods

Case Report

The patient was a male (born after an uncomplicated pregnancy) with a birth weight of 3.2 kg and normal body length and head circumference. The family history was uneventful. At 43 days of life, the patient presented with respiratory distress including cough, fever, poor feeding and pale grey skin colour. Haematological investigations revealed normocytic anaemia, thrombocytopaenia and some features of haemolysis: haemoglobin 4.2 g/dL, reference range (RR) 9–13.5; haematocrit 11%, RR 29–41; mean corpuscular volume 87 fl, RR 74–90; mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration 32 pg/L, RR 25–35; platelets 20,000 u/mm3, RR 150,000–500,000; reticulocyte count 1.3%, RR 1–2.5%; bilirubin 5.4 mg/dL, RR 0.2-1; lactate dehydrogenase 1162 UI/L, RR < 776; haptoglobin < 40 mg/L, RV 70–3100; and negative direct and indirect Coombs tests. An erythrocyte microscopic examination showed anisopoikilocytosis, Jolly corpuscles and some isolated schistocytes. The bone marrow aspiration revealed erythroid megaloblastic changes, granulocytic and dyserythropoietic features (karyorrhexis and pycnosis), and the megakaryocytic series was diminished (suggesting megaloblastic bone marrow changes due to ineffective erythropoiesis). The following renal function parameters were observed: haematuria, more than 100 red blood cells per high-power field; proteinuria, 30 mg/dL in a random urine sample, RV: 0–8; and hypertension (115/57) with slightly impaired renal function, serum urea 52 mg/dL, RV 7–45, serum creatinine 0.55 mg/dL; RV <0.5. C-reactive protein was normal (<5 mg/L). The patient presented with respiratory arrest and bradycardia while undergoing a transfusion of packed red cells and was admitted to the PICU. Biochemical analysis revealed homocystinuria (3,517 mmol/g creatinine, RV <20), hyperhomocysteinaemia (257 μmol/L, RV <7.5), a low plasma methionine level (2 μmol/L; RV 12–37), normal methylmalonic acid excretion and normal serum folate and cobalamin concentrations (data not shown); these data suggest a cobalamin genetic disorder. The treatment was initiated with hydroxocobalamin (1 mg per day administered intravenously for 4 days), folic acid (40 mg per day administered orally for 7 days), betaine (250 mg/kg/day for 2 days), carnitine (100 mg/kg/day intravenously every 8 h for 3 days) and pyridoxine (150 mg/day every 8 h for 3 days) with no significant clinical improvement. The patient had high blood pressure that was resistant to nifedipine and hydralazine boluses, decreased urine output, oedema, hyponatremia, proteinuria, haematuria and bloody diarrhoea. The thrombocytopaenia was persistent despite transfusions. Due to the severe neurological affectation, the patient expired despite mechanical respiratory support.

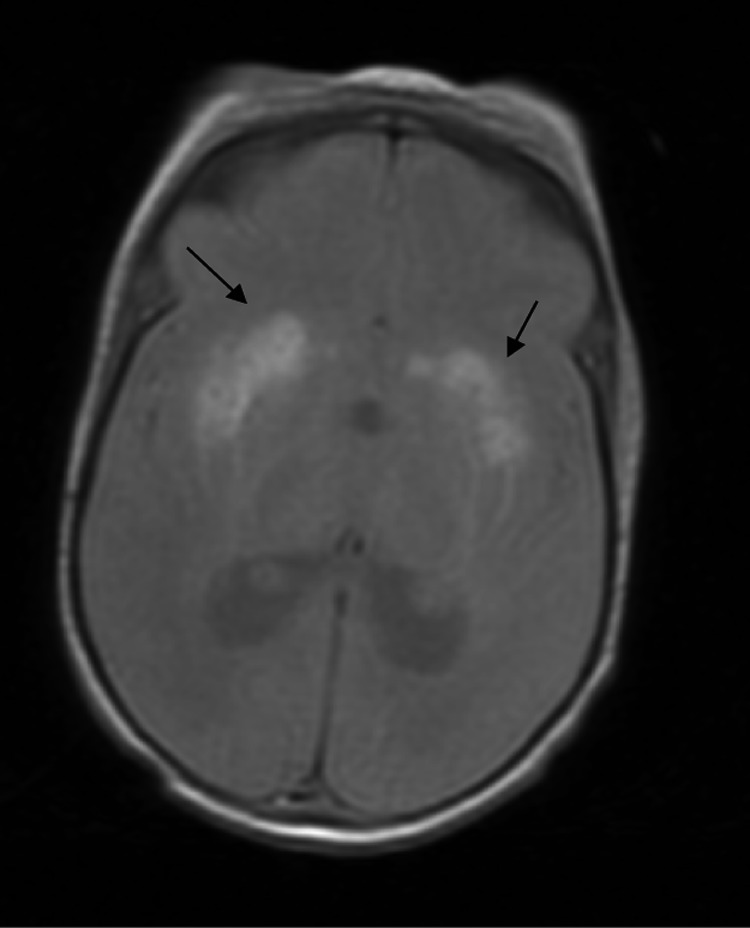

Magnetic resonance imaging showed severe impairment of the white matter (predominantly bifrontal) and a significant decrease in the grooves and ischaemic-haemorrhagia at the basal ganglia. A delay in myelination was observed. As shown in Fig. 1 (MRI axial T2 sections), we observed bilateral high intensity in the lenticular nuclei and the head of the caudate nuclei that was suggestive of haematic content.

Fig. 1.

Axial T2 section: An MRI of the brain shows bilateral high intensity in the lenticular nuclei and the head of caudate nuclei that is suggestive of haematic content (black arrows)

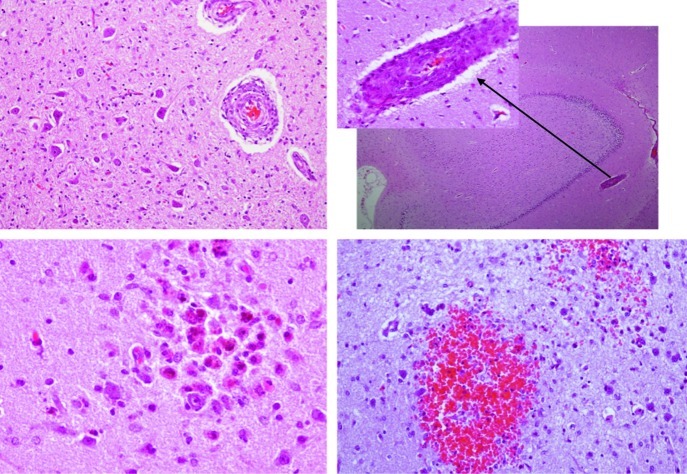

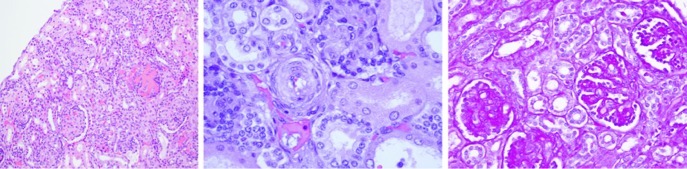

After the autopsy, the pathological findings in the kidneys showed poor cortical-medullary differentiation, and the glomeruli and arterioles were affected histologically. The glomerular component showed thickened capillary walls with endothelial cell swelling and other glomeruli in which the dilatation of the capillaries was prominent. Some areas of mesangiolysis were also observed. The vascular changes affected the intraglomerular arterioles with marked myointimal proliferation and narrowing of the vascular lumen (Fig. 2). In the central nervous system, haemorrhaging affected the putamen and the thalamus; we observed diffuse white matter involvement with spongiosis and necrosis, and severe astrocytosis. Microangiopathy was also observed with increased vessel wall thickness, reduced arterial inner diameter and capillary oedema. In the cerebellum, areas of necrosis and haemorrhage were detected: abnormalities in the cerebellar peduncles, the tegmentum and the bulbar olive were seen (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The histopathological findings in the patient kidney. Microangiopathy was observed with thickened vessel walls and a reduction of the arterial inner diameter and capillary oedema. Left panel: glomeruli with thickening of the capillary walls and glomeruli with prominent capillary dilatation (×100). Middle panel: marked myointimal proliferation with narrowing of the lumen (×400) observed with haematoxylin-eosin staining. Right panel: PAS staining (×200) disclosed glomerular mesangiolysis

Fig. 3.

The histopathological findings show microangiopathy in different areas of central nervous system. Upper left panel: cerebellar peduncles with myointimal proliferation of vessels. Upper right panel: vessel myointimal proliferation in the hippocampus. Lower panels: microhaemorrhage with a high content of macrophages containing hemosiderin, microglia activation (left) and recent bleeding in the cerebellum (right)

Methods

Biochemical Analysis

A skin biopsy was performed under standard conditions, and cultured skin fibroblasts were obtained for biochemical studies. Methionine and serine synthesis were studied by [14C] formate incorporation into amino acids after incubation with different OH-cobalamin quantities (Fowler et al. 1997). The uptake of [57Co] labelled cobalamin and synthesis of cobalamin coenzymes was measured as previously referred (Zavadakova et al. 2002). The propionate incorporation in intact fibroblasts was measured after cell incubation with and without a high OH-cobalamin concentration (Willard et al. 1976). Complementation analysis of intact patient cells and fibroblasts treated with 40% polyethylene glycol was performed by the incorporation of 14C-formate into methionine. As known complementation groups, the cblD, cblG and cblE cells were used.

Genetic Studies

The molecular analysis of the MTRR gene was carried out on genomic DNA and cDNA. The total mRNA and the genomic DNA were isolated from cultured fibroblasts from the patient using the MagnaPure system (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), following the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-PCR was performed using the SuperScript III First-Strand enzyme (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To identify mutations in the MTRR gene, a sequence analysis of its cDNA and genomic DNA was performed using the primers designed by the Primer 3 software (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi). The sequence will be provided upon request. The identified changes were confirmed by sequencing the corresponding genomic DNA region and the parent samples to ensure that the changes were in different alleles and to rule out the presence of a large genomic rearrangement. For the genetic studies, written permission was obtained from the patient’s parents. The ethical Committee of Hospital Sant Joan de Déu approved the study.

Results

The biochemical results are presented in Table 1. There was deficient formation of methionine in the cells grown in normal medium and under supplementation with increasing concentrations of OH-cobalamin with no increase of serine formation. The total content of the radioactive cobalamin was normal, and the methyl-form of cobalamin synthesis was low. The formation of the adenosyl-form of cobalamin was in the normal range. The 14C propionate incorporation was within the normal values for the fibroblasts cultured with and without OH-cobalamin. Finally, complementation analysis of the patient fibroblasts confirmed that the patient belonged to the cblE complementation group (MTRR gene).

Table 1.

Biochemical data in cultured skin fibroblasts from the case with cblE deficiency. A severe deficient methionine synthesis (first lane) was observed with low methylcobalamine (Me-Cbl) uptake (second lane), and normal propionate incorporation (third lane), indicating a cblE defect. For the complementation analysis (fourth lane), patient cells were mixed with known complementation groups with or without polyethyleneglycol (PEG) and methionine formed (nmol/mg protein/16 h) from 14C-formate was calculated. Patient cells complemented with the cblD and the cblG mutatnt cells, but not with the cblE cell line, confirming the cblE complementation group of the patient

| Conditions | Patient | Parallel control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methionine synthesis | OH–Cbl 0 μg/L OH–Cbl 1,000 μg/L |

0.13 (nmol/16 h) 0.22 (nmol/16 h) |

2.46 (nmol/16 h) 2.66 (nmol/16 h) |

| Me-Cbl uptake | % of total (57Co) | 10% | 58% |

| Ado-Cbl uptake | 24% | 11% | |

| Propionate incorporation | OH–Cbl 0 μg/L | 11.7 (nmol/mg.16 h) | 12.8 (nmol/mg.16 h) |

| OH–Cbl 1,000 μg/L | 13.8 (nmol/mg.16.h) | 18.4 (nmol/mg.16 h) | |

| Complementation | Difference | Positive control | |

| Patient/cblD | (+PEG)–(–PEG) | + 0.49 | + 0.47 |

| Patient/cblE | (+PEG)–(–PEG) | –0.07 | |

| Patient/cblG | (+PEG)–(–PEG) | +0.85 |

The patient harboured the two novel changes c.1324_1327 + 12del15 and c.125A>G (https://portal.biobase-international.com/hgmd) in the MTRR gene. The former mutation affected the normal splicing process of exon 9 (RT-PCR analysis in heterozygous state showed skipping of the entire exon 9), which generated a loss-of-function mutation (p.Leu442fs). The second change (p.Asp42Gly) was classified as ‘damaging’ by the PolyPhen computational prediction algorithm (genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2).

Discussion

Here, we present a new case of the cblE defect with HUS features, which for the first time represents a severe phenotype with an associated fatal outcome. The HUS diagnosis was based on the presence of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (some schizocytes were observed on the peripheral blood smear), thrombocytopaenia, renal involvement (haematuria and slightly impaired renal function) and microangiopathy in the kidneys with arteriolar rather than glomerular involvement (Giménez et al. 2008). Haemolysis was demonstrated by increased LDH and bilirubin levels and decreased haptoglobin concentrations. Considering these data (the presence of haemolysis, the morphological features of erythrocytes and the megaloblastic changes observed after the bone marrow examination) a plausible explanation for these findings could be haemolysis triggered by microangiopathy and an ineffective erythropoiesis due to a functional cobalamin deficiency. Haemolysis would explain why no megaloblastic changes appeared in the peripheral smear and the ineffective erythropoiesis why no increased reticulocyte values were observed.

In children, the prognosis is poor for HUS associated with other cobalamin disorders, and the mortality rate is high, even when symptoms present early (Chenel et al. 1993; Sharma et al. 2007). The rapid and fatal evolution of the condition despite early treatment with vitamins and cofactors was noteworthy in our case. It has been suggested that hydroxocobalamin treatment may cure HUS, but the severe neurological affectation in our case may have contributed to the fatal evolution (Chenel et al. 1993; Tuchman et al., 1988). It seems that the earlier the presentation the worse the prognosis; a 33% mortality rate has been documented in patients with the cblC defect that manifested in the newborn period (Rosenblatt et al. 1997; Rosenblatt Whitehead 1999). Neuroimaging findings and neuropathological studies supported the severity of the clinical evolution, and several brain areas were affected, most likely triggered by the vascular lesions. Microangiopathy in the kidneys and the central nervous system (affecting arteriola with vessel wall hyperplasia and decreased inner diameter and in the capillary circulation) was observed after the histopathological studies supported the relationship between the cblE defect and the vascular damage. An increase in plasma total homocysteine might provide a pathophysiological explanation for findings, as the impairment of vascular physiology by hyperhomocysteinaemia (involving different mechanisms) has been consistently demonstrated (Stamler et al. 1993; Hajjar 1993; Rodgers and Kane 1986). However, the pathophysiological mechanisms related to the association between hyperhomocysteinaemia and HUS is at present unknown, and this matter deserves further investigation.

At the gene level, the patient harboured two novel pathogenic changes according to the experimental data and the computational prediction algorithm. This pathogenicity was proven by the biochemical analysis of the patient fibroblasts, which confirmed an important reduction of methionine synthesis and methylcobalamin uptake, and also by the complementation analysis with the cblE fibroblasts.

In conclusion, cblE-type homocystinuria may be associated with hemolytic-uremic syndrome features with fatal outcome. Our patient exhibited vascular damage, possibly related to the severe hyperhomocysteinaemia.

Acknowledgements

The groups are funded by the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, an initiative of the MICINN, Spain.

Synopsis

The vascular involvement in the kidneys and the central nervous system was demonstrated by the contribution of the cblE defect to patient mortality, despite early diagnosis and treatment.

Contribution Details

D. Palanca and J. Ortiz assisted with the clinical data collection and drafting of the manuscript. A. Garcia-Cazorla contributed to the neurological evaluation and the critical revision of the manuscript. C Jou, V. Cusí and M. Suñol interpreted the histopathological studies and assisted with the critical revision of the manuscript. T. Toll provided the differential diagnosis and assisted with the haematological data collection and the manuscript revision. B. Perez contributed to the molecular genetic analysis and interpreted the results. A. Ormazabal and R. Artuch provided the biochemical diagnosis and interpretation and assisted with the study design and drafting of the manuscript. B. Fowler assisted with the complementation studies and the interpretation of results.

Guarantor

Rafael Artuch

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Details

The authors confirm that the study content has not been influenced by the study sponsors. Financial support was provided by CIBERER (an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III) and from the “Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca-Agaur” (2009SGR00971). RA and AGC are supported by the “Intensificación de la actividad Investigadora” programme of ISCIII. BF was supported by Swiss National Foundation, grant number 320000_122568/1. All grants are competitive and public.

Ethics Approval

The parents of the infant in the index case signed an informed consent agreement in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 revised in Edinburgh in 2000. Our hospital ethics committee approved the study.

References

- Chenel C, Wood C, Gourrier E, Zittoun J, Casadevall I, Ogier H. Neonatal hemolytic-uremic syndrome, methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria caused by intracellular vitamin B 12 deficiency. Value of etiological diagnosis. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1993;50:749–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler B, Whitehouse C, Wenzel F, Wraith JE. Methionine and serine formation in control and mutant human cultured fibroblasts: evidence for methyl trapping and characterization of remethylation defects. Pediatr Res. 1997;41:145–151. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199701000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty MT, Perlman EJ, Martin LS, et al. Cobalamin C defect associated with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1992;120:934–937. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81967-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez A, Camacho JA, Vila J, et al. Síndrome hemolítico-urémico. Revisión de 58 casos. An Pediatr. 2008;69:297–303. doi: 10.1157/13126552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar KA. Homocysteine-induced modulation of tissue plasminogen activator binding to its endothelial cell membrane receptor. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2873–2879. doi: 10.1172/JCI116532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T, Levy J, Lee M, Kaicker S, Nicholson JF, Kane SA. Cobalamin C disease presenting as hemolytic-uremic syndrome in the neonatal period. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:327–329. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200205000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrune P, Zittoun J, Duvaltier I, et al. Haemolytic uraemic syndrome and pulmonary hypertension in a patient with methionine synthase deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:734–739. doi: 10.1007/s004310051190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P, Horneff G, Hennermann JB. A rare error of intracellular processing of cobalamine presenting with microcephalus and medaloblastic anemia: a report of 3 children. Klin Pediatr. 2007;219:361–367. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noris M, Remuzzi G. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1035–1043. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers GM, Kane WH. Activation of endogenous factor V by a homocysteine-induced vascular endothelial cell activator. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1909–1916. doi: 10.1172/JCI112519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt DS, Whitehead M. Cobalamin and folate deficiency: acquired and hereditary disorders in children. Semin Hematol. 1999;36:19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt DS, Aspler AL, Shevell MI, et al. Clinical heterogeneity and prognosis in combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria (cblC) J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997;20:528–538. doi: 10.1023/A:1005353530303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo P, Doyon J, Sonsino E, Ogier H, Saudubray JM. A congenital anomaly of vitamin B12 metabolism: a study of three cases. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:504–512. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90127-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma AP, Greenberg CR, Prasad AN, Prasad C. Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) secondary to cobalamin C (cblC) disorder. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:2097–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovby F. Disorders of sulfur amino acids. In: Blau N, Duran M, Blaskovics ME, Gibson KB, editors. Physician’s guide to the laboratory diagnosis of metabolic diseases. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Osborne JA, Jaraki O, et al. Adverse vascular effects of homocysteine are modulated by endothelium-derived relaxing factor and related oxides of nitrogen. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:308–318. doi: 10.1172/JCI116187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman M, Kelly P, Watkins D, Rosenblatt DS. Vitamin B 12-responsive megaloblastic anemia homocystinuria and transient methylmalonic aciduria in Cbl E disease. J Pediatr. 1988;113:1052–1056. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80582-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaseca MA, Vilarinho L, Zavadakova P, et al. CblE type of homocystinuria: mild clinical phenotype in two patients homozygous for a novel mutation in the MTRR gene. J InheritMetab Dis. 2003;26:361–369. doi: 10.1023/A:1025159103257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard HF, Ambani LM, Hart AC, Mahoney MJ, Rosenberg LE. Rapid prenatal and postnatal detection of inborn errors of propionate, methylmalonate, and cobalamin metabolism: a sensitive assay using cultured cells. Hum Genet. 1976;34:277–283. doi: 10.1007/BF00295291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Leclerc D, Rosenblatt DS, Gravel RA. Molecular basis for methionine synthase reductase deficiency in patients belonging to the CBLE complementation group of disorders in folate/cobalamin metabolism. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2009–2016. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavadakova P, Fowler B, Zeman J, Suormala T, Pristoupilova K, Kozich V. CblE type of homocystinuria due to methionine synthase reductase deficiency: clinical and molecular studies and prenatal diagnosis in two families. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:461–76. doi: 10.1023/A:1021299117308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavadakova P, Fowler B, Suormla T, et al. CblE type of homocystinuria due to methionine synthase reductase deficiency: functional correction by minigene expression. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:239–247. doi: 10.1002/humu.20131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerhackl LB, Besbas N, Jungraithmayr T, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathophysiology of atypical and recurrent hemolytic uremic syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32:113–120. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]