Abstract

Little is published regarding the effect of advertising for kidney donors on transplant centers. At our center, families of nine children used media appeals. Per candidate, there were 8 to 260 potential donor calls, 92 (11.6%) were medically ineligible, 326 (41.1%) voluntarily did not proceed or an alternate donor had been approved, 38 (4.8%) were ABO incompatible, and 327 (41.1%) had positive crossmatch or unsuitable human leukocyte antigens. Media appeals resulted in four living donor transplants and five nondirected donors to other candidates, and we made directed changes in our center. The ethical debate of advertising for organ donors continues.

Keywords: Media appeals, Pediatric kidney transplant, Kidney donor

Kidney transplantation offers a survival advantage to children with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (1) and profoundly impacts school attendance, quality of life, and growth (2). Highly sensitized children have particular difficulty in finding compatible donors (3). These factors, with the extra-renal issues affecting the lives and families of any pediatric patient with renal failure, create added pressure to obtain kidney donors. The use of media to solicit living unrelated kidney donors has become a more common practice. At our center, nine families of children without compatible donors opted, independent from the transplant center, to engage the media to find a living donor. Our program does not encourage media appeals, and we had no plan for discussion with families who used the media and no plan of how to respond to media-generated calls.

We reviewed the outcome of media appeals on the lives of these children and our transplant center. We describe the modifications we have made in response to issues created by these appeals, including, but not limited to, the increased workload for our center, coordinators, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) laboratory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Minnesota. Between January 2000, and July 2009, 165 children were evaluated for kidney transplant at the University of Minnesota. The families of nine children without compatible living donors engaged the media in an attempt to identify a willing donor.

Potential donors calling our center underwent a telephone screening interview with a transplant coordinator; if eligible, a packet with general transplant information, surgical risks to the donors, expected surgical recovery time, and donor evaluation procedures was mailed. If the prospective donor remained interested or recontacted the center, blood testing and donor evaluation were scheduled.

We reviewed the records of these nine children. Demographic data, including birth date, gender, age at initiation and duration of dialysis, transplant age, HLA information, and graft and patient outcomes were ascertained from medical records. We studied the number of donors who responded to the appeals, who were ineligible before and after proceeding with donor workup, and who were eligible and withdrew. For those proceeding to donation, we studied associated transplant outcomes. For those undergoing evaluation and subsequently denied eligibility as transplant donors, we categorized reasons for denial as follows: ABO incompatibility, presence of donor-specific antibodies, and/or crossmatch incompatibility or exclusion due to medical comorbidity (e.g., failed psychological evaluation, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and body mass index >30 kg/m2). Because of the manner in which data are entered into our database, donors who failed to recontact the center and donors who did not proceed because a previous donor caller had already been approved were categorized together as “No Further Contact.”

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze and present the data.

RESULTS

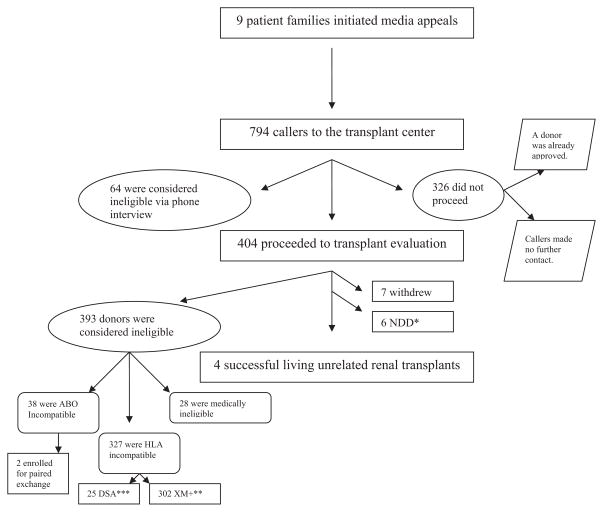

Of the nine children studied, seven had ESRD as a result of congenital renal anomalies (Table 1), and six were previous kidney transplant recipients. At the time of referral for transplant evaluation, eight were on dialysis (range 5–52 months) and seven lived more than 60 miles from a pediatric dialysis center, requiring relocation to temporary residential facilities. The children were aged 7 months to 14.2 years (mean 6.7 years) at the time of referral. On initial pretransplant evaluation, eight (88.9%) were sensitized with increased panel reactive antibodies (class I: 2%–96%; class II: 46%–100%). The unsensitized child had three related willing donors who were ruled out because of advanced age, incompatible blood group, and her mother was medically ineligible. Of the nine children, eight (89%) waited for more than 1 month (1–14.5 months) from the time of transplant referral before making a media appeal. The types of media varied and included local television (n=4, 44.4%), websites (n=2, 22.2%), church or work bulletins (n=2, 22.2%), and local newspapers (n=3, 33.3%; Table 2). Three (33.3%) families used multiple media types (Table 2). In response to the media appeals, there were 8 to 260 potential donors per candidate who called the transplant center for initial screening (n=794: age range 18 –73 years; n=557: 70% female; Table 3). Of the 794 callers, 64 (8.1%) were excluded as donors based on the telephone interview. Of the remainder, 326 did not proceed to evaluation (as described earlier, this may have been because they failed to recontact our center or because there was already an approved donor for the specific child). Four hundred four respondents proceeded with the donor evaluation; 393 (97.3%) were denied as potential donors: 28 (6.9%) did not meet medical health criteria on evaluation by an adult nephrologist, 38 (9.4%) were ABO incompatible, 302 (74.8%) had positive crossmatches, and 25 (6.2%) had HLA antigens to which the child had donor-specific antibodies (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the children whose family used the media

| Age at time of referral for transplant evaluation | 7 mo to 14.2 yr (mean 6.7 yr) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Males | 7 (77.8) |

| Females | 2 (22.2) |

| Cause of end-stage renal disease, n (%) | |

| Congenital anomalies | 7 (77.8) |

| Nephronophthisis | 1 (11.1) |

| Cortical necrosis | 1 (11.1) |

| Duration of dialysis before transplant referral | 5 to 52 mo (mean 12.3 mo) |

| Degree of sensitization (%) | |

| Class I panel reactive body | 2–96 |

| Class II panel reactive body | 46–100 |

| No. previous transplants, n (%) | |

| 0 | 3 (33.3) |

| 1 | 5 (55.6) |

| 2 | 1 (11.1) |

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of media used by the families of our nine patients

| Types of media | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Local television | 4 (44.4) |

| Websites | 2 (22.2) |

| Church bulletin | 1 (11.1) |

| Work bulletin | 1 (11.1) |

| Local newspapers | 3 (33.3) |

| Multiple sources | 3 (33.3) |

TABLE 3.

Demographic data and outcomes of the potential donors who called in response to the media

| Patient | Type of media used | No. callers | Female callers, n (%) | Age of potential donors (yr) | Outcomes of the potential donors who called the center

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to make further contact, n (%) | Denied because of medical issues, n (%) | ABO incompatible, n (%) | Crossmatch incompatible or DSA, n (%) | Transplant information | |||||

| 1 | Local TV and website | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 26–41 | 2 (25) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25) | 1 (12.5) | 1 DD |

| 2 | Local TV | 66 | 46 (69.7) | 18–69 | 44 (66.6) | 4 (6.1) | 11 (16.7) | 7 (10.6) | 1 DD |

| 3 | Local newspaper | 108 | 83 (76.9) | 20–73 | 40 (37) | 6 (5.6) | 8 (7.4) | 54 (50) | 1 NDD; 1 DD |

| 4 | Church bulletins | 20 | 15 (75) | 20–60 | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | 0 (0) | 8 (40) | 1 DD |

| 5 | Local newspaper | 260 | 176 (67.7) | 18–76 | 104 (40) | 28 (10.8) | 10 (3.8) | 116 (44.6) | Not yet transplanted |

| 6 | Website and local TV | 38 | 28 (73.7) | 25–65 | 11 (28.9) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 24 (63.2) | 1 LURD; 1 NDD |

| 7 | Local newspaper and TV, national TV, website | 258 | 179 (69.4) | 20–69 | 98 (38) | 34 (13.2) | 5 (1.9) | 116 (44.9) | 1 LURD; 4 NDD |

| 8 | Websites | 27 | 21 (77.8) | 24–69 | 17 (62.9) | 7 (25.9) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1 LURD |

| 9 | Internal news story at company father delivered packages to | 9 | 6 (66.7) | 41–51 | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 1 LURD |

| Total | 794 | 557 (70.2) | 18–73 | 326 (41.1) | 92 (11.6) | 38 (4.8) | 327 (41.1) | 4 DD; 4 LURD; 6 NDD | |

DSA, donor-specific antibody; DD, deceased donor; LURD, living unrelated renal donor (or living responder donor); NDD, nondirected donor.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the workflow at our center and the process of exclusion versus acceptance of the volunteer callers initiated by these public pleas for kidneys. HLA, human leukocyte antigen; DSA, donor-specific antibody; XM, crossmatch; NDD, non-directed donation.

Of the nine children, four were successfully transplanted from a responder 3 weeks to 4.5 months after the media plea. All four continued to do well 3 to 5 years post-transplant. The four donors had no postoperative complications. One donor subsequently sustained residual brain damage from a motor vehicle accident and one required umbilical hernia repair, both events unrelated to the nephrectomy surgery. Of the remaining five children, four received deceased donor kidneys while living donor evaluations were in progress, and one remains untransplanted (but two responders through the media have enlisted for a Paired Exchange for the patient). Six donors recruited through media contacts, who were not compatible with the intended transplant recipient, offered to donate a kidney to other listed patients. Our staff did not discuss Paired Exchange or nondirected donation to responders to these media events, these donors were self-motivated. Of these six potential nondirected donors, two have had no operative complications, two have been approved and the transplants are pending, and two were deemed medically ineligible after evaluation by a nephrologist.

Within minutes of the media broadcasts, our call center was inundated with calls. Our donor coordinators were overwhelmed, forcing many callers to voice mail. The delayed response in making contact with callers lead to frustration for callers and recipient families. When donor candidates began sending blood samples for ABO typing, crossmatching, and tissue typing, the HLA laboratory also faced a precipitous increase in workload. Parents of two of the children asked potential donors to respond directly to them and became involved in the screening of donors. This circumvented our traditional approach of direct communication with the donor without the involvement of patient’s family.

In response to these issues and in anticipation of future appeals, our transplant center protocols have been modified. We have established a specific centralized referral line for donor calls to alleviate the workload on our donor coordinators. We added the referral line to an existing hospital service for centralized calls, and its staff gathers demographic information, initiates the donor record in the transplant database, and then notifies the donor coordinator who is responsible for donor contact and medical screening. These changes enable us to provide donors with a timely response and alleviated demands on the transplant coordinators. The acute increase in HLA laboratory tissue typing and crossmatch was improved by limiting donor tissue typing to crossmatch negative candidates. This eliminated considerable workload for the laboratory and cut costs because tissue typing costs approximately $1000/donor, whereas a crossmatch costs less than $250/donor.

We have modified the literature that we provide to potential recipients and families, on finding a living donor, to include a section on “media appeals.” Patients and their families are asked to discuss the idea of a media appeal with their transplant coordinator who can assist in appropriate public notices, which ideally include required blood type and medical issues that might prevent a person from donating. Families are instructed to have potential donors contact us directly and to give potential donors methods to find reliable resources regarding organ donation.

We have also set up a hospital-staffed Living Donor Information Line to help guide patients, families, and their potential donors throughout the process. Patients and donors who call this line, speak to an individual who informs them regarding basic eligibility criteria and directs their questions appropriately.

DISCUSSION

It should not be surprising that parents of children without suitable familial donors would feel the need to go beyond the usual methods used by transplant centers to expedite kidney donor identification. First, there has been little increase in donor numbers; second, sensitized patients are particularly disadvantaged in finding HLA compatible donors. Despite the pediatric advantage on the waitlist, sensitized children have long wait times. Third, dialysis is not benign with suboptimal survival (5-year pediatric survival on dialysis is 73%– 82% depending on age) (4) and risk of malnourishment and poor school performance (2). These adverse effects are countered posttransplant by accelerated head growth to the normal range, improved developmental test scores, and improvement in growth (2). Fourth, the limited locations of pediatric dialysis centersforce many families to be uprooted into temporary quarters. It seems unlikely that any of these issues will be resolved soon, and parents of children with ESRD will continue to use media appeals for kidney donors. Because graft and patient outcomes are comparable for related and unrelated living donor kidney recipients (5, 6), surgical advances have minimized adverse effects on donors (estimated mortality, 0.03% [7]), and average quality of life scores for donors are not altered (8), we anticipate an increase in the number of families using the media.

In our series, four children (44%) found kidney donors through media appeals and all are doing well after transplant. In addition to the direct benefit to these recipients, media appeals have other potential advantages. They create an increased awareness of the need for donors among the public. And, as seen in our respondents, the appeals may lead to nondirected kidney donation. Although our center still does not discuss nondirected donation with potential donors, as a result of our experience with these nine children, we now inform ABO incompatible donors about the Paired Exchange Program. Although the donors in our series who opted for Paired Exchange or nondirected donation to the transplant waiting list were self-motivated, it is possible that there may be more willing to volunteer for the Paired Exchange Program now that we discuss that option with interested donors, and this is worthy of further study.

As a result of our experience, a specific centralized referral line for donor calls has improved our response time and alleviated demands on the transplant coordinators. Limiting donor tissue typing to crossmatch-negative donor candidates has significantly reduced costs and burden on our HLA laboratory. All families are now advised to notify the transplant center before any media exposure so that families can be prepared to deliver the most focused plea and so that we are adequately prepared to deal with the response. This has seemed to increase the satisfaction of the patients and their families and the volunteer donors who call our center.

The increased sophistication by candidates and their families with the use of media will introduce new problems to kidney transplantation. Transplant centers will need to develop procedures to address the various issues that are inevitable as we transition to the modern era of social media savvy.

The social justice and ethics of using the media for organs donation is a necessary debate: the path this debate may take is likely unpredictable. Although one could argue, as we have illustrated here, that using the media increases donor awareness and the availability of kidneys for everyone on the waiting list, the potential direct and indirect impact this might have on less fortunate or less connected families needs to be considered. The question might also arise as to whether this type of appeal should be regulated by law. Although it is constitutionally unlikely that freedom of speech by parents appealing for their children could possibly be regulated, this again is worthy of discussion. Should we encourage patients to use the media? The debate, as of now, is unresolved.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

P.V. participated in research design, performance of the research, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript; C.G. participated in performance of the research and writing of the manuscript; M.M. participated in research design and writing of the manuscript; and A.M. participated in research design, performance of the research, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gillen DL, Stehman-Breen CO, Smith JM, et al. Survival advantage of pediatric recipients of a first kidney transplant among children awaiting kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nevins TE. Overview of pediatric renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1991;5(2 pt 2):150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claas FH, Doxiadis II. Management of the highly sensitized patient. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:569. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Alessandro AM, Sollinger HW, Knechtle SJ, et al. Living related and unrelated donors for kidney transplantation. A 28-year experience. Ann Surg. 1995;222:353. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00012. discussion 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park K, Kim YS, Lee EM, et al. Single-center experience of unrelated living-donor renal transplantation in the cyclosporine era. Clin Transpl. 1992:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najarian JS, Chavers BM, McHugh LE, et al. 20 years or more of follow-up of living kidney donors. Lancet. 1992;340:807. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, et al. Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]