Abstract

Background and Aims

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced chronic inflammation may induce oxidative stress which could compromise the repair of damaged DNA, rendering cells more susceptible to spontaneous or mutagen-induced alterations, the underlying cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In the current study we examined the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulting from HCV infection and evaluated its effect on the host DNA damage and repair machinery.

Methods

HCV infected human hepatoma cells were analyzed to determine (i) ROS, (ii) 8-oxoG and (iii) DNA glycosylases NEIL1, NEIL2, OGG1. Liver biopsies were analyzed for NEIL1.

Results

Human hepatoma cells infected with HCV JFH-1 showed 30–60-fold increases in ROS levels compared to uninfected cells. Levels of the oxidatively modified guanosine base 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) were significantly increased sixfold in the HCV-infected cells. Because DNA glycosylases are the enzymes that remove oxidized nucleotides, their expression in HCV-infected cells was analyzed. NEIL1 but not OGG1 or NEIL2 gene expression was impaired in HCV-infected cells. In accordance, we found reduced glycosylase (NEIL1-specific) activity in HCV-infected cells. The antioxidant N-acetyl cystein (NAC) efficiently reversed the NEIL1 repression by inhibiting ROS induction by HCV. NEIL1 expression was also partly restored when virus-infected cells were treated with interferon (IFN). HCV core and to a lesser extent NS3-4a and NS5A induced ROS, and downregulated NEIL1 expression. Liver biopsy specimens showed significant impairment of NEIL1 levels in HCV-infected patients with advanced liver disease compared to patients with no disease.

Conclusion

Collectively, the data indicate that HCV induction of ROS and perturbation of NEIL1 expression may be mechanistically involved in progression of liver disease and suggest that antioxidant and antiviral therapies can reverse these deleterious effects of HCV in part by restoring function of the DNA repair enzyme/s.

Keywords: DNA glycosylase, hepatitis C virus, interferon, N-acetyl cystein, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is prevalent in approximately 2% of the world’s population and is the leading cause of acute and chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma1 but the mechanisms of pathogenesis are still not clear. As a member of the Flaviviridae family, HCV contains a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 9.5 kb. The viral genome is processed by a combination of host- and virus-encoded proteases into at least 10 viral structural and non-structural (NS) proteins are arranged in the order of core, E1, E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B.2,3 Our previous study with 65 genotype 1-infected subjects showed that the structural protein, core antigen, is closely associated with HCV infection, while the NS protein, NS3 antigen, is more tightly associated with HCV replication activity and liver disease.4

Oxidative stress has emerged as a key player in the progression of HCV-induced liver pathogenesis.5,6 Increased oxidative stress in hepatitis C occurs in livers, possibly as a result of chronic inflammation, although a role of viral factors in the continued generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the liver has not been evaluated. 6 HCV core protein expression causes an increase in mitochondrial ROS production in transgenic mice.7 In human hepatocyte-derived cells, HCV core and NS5A proteins both induce ROS and nitrogen species formation thus increasing oxidative and nitrosative stress.8

Several studies have suggested that suppression of DNA repair might be a crucial consequence of chronic oxidative stress in HCV-infected cells. Zekri and colleagues have reported reduced expression of mismatch repair genes in HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma.9 Expression of HCV core protein was also found to reduce the repair of ultraviolet-induced DNA damage in human hepatoma cells.10 Aukrust et al. reported that HIV-infected patients, particularly those with advanced disease, demonstrate increased levels of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) in CD4+ T cells and a marked decline in DNA glycosylase activity for the repair of oxidative base lesions in these cells.11 Collectively, the data suggest that oxidative stress resulting from either inflammation or viral infection leads to accumulation of DNA damage in cells.

Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidation of DNA is complex, leading to a multitude of modifications to DNA bases. It is now widely accepted that DNA damage is involved in the etiology of most oxidative stress-mediated diseases.12 Several types of oxidative DNA lesions have been reported, including strand breaks, baseless sugars and oxidized base residues, with 8-oxoG and 5-hydroxycytosine (5-ohC) representing the most frequent mutagenic base lesions.13,14

To counteract the biological effects of DNA damage, DNA repair mechanisms have specifically evolved. Oxidized base lesions in DNA are repaired through a highly conserved base excision repair (BER) pathway15,16 that is initiated with excision of the damaged base by DNA glycosylases, followed by DNA strand cleavage at the lesion site. Four major DNA glycosylases, namely, NTH1, OGG1, NEIL1 and NEIL2, have been characterized in human cells for the removal of oxidative base residues, with the NEIL present only in vertebrates. NTH1, NEIL1 and NEIL2 remove oxidized pyrimidine such as 5-OHU.C, whereas OGG1 removes oxidized purines such as 8-oxoG.17 However, NEIL1 also provides a vital backup function for OGG1 for the removal of 8-oxoG and shows preference for ring-opened purines— formamidopyrimidine (Fapy)-A and -G—which represent blocks to replication.18 Surprisingly, mice nullizygous for Ogg1 or Nth1 have no strong phenotype and do not show a significant increase in tumor incidence.19–21 These reports indicate that repair pathways heralded by the more recently discovered NEIL might be more than a backup system for OGG1 and NTH1 in maintaining the functional integrity of mammalian genomes under oxidative stress. Again, it has been proposed that NEIL with special reference to NEIL1 are preferentially involved in repair of oxidized bases from the active sequences during replication or transcription18 which should be more urgent than the repair of inactive sequences.

The present study demonstrates that HCV infection induces ROS, generates pre-mutagenic lesions and causes modulation of the glycosylase, NEIL1 in vitro, with crucial involvement of HCV core among others. Analysis of explant liver biopsy specimens from HCV-infected patients revealed repression of NEIL1 associated with severe liver disease compared to uninfected liver with no disease.

Methods

Cells and HCV infection

Infection of the Huh7.5.1 cell with the HCV 2a JFH-1 clone was performed as described by Wakita et al.22 α-Interferon (IFN-α) (ROFERON-A; Roche US Pharmaceuticals, SA, USA) and N-acetyl Cystein (NAC, Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) were solubilized in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) as instructed by the manufacturer. IFN-α and NAC were added to the Huh7.5.1 cells (final concentration 100 U/mL and 10 µM, respectively) at the time of infection and harvested for real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) at 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection.23 The tetracycline-regulated HeLa cell line expressing HCV core24 was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 U of penicillin G/mL, 50 µg of streptomycin/mL, 500 µg of G418 (Geneticin; Sigma Chemical)/mL and 1 µg of tetracycline (Sigma Chemical)/mL.

Transfection of HCV genes

Hepatitis C virus genes core, NS3-4, and NS5A were used for transient transfection along with parental empty vector pcDNA3.1. The day prior to transfection, 0.5 × 106 Huh7.5.1 cells were plated overnight in chamber slides. Endotoxin-free plasmid DNA (0.5 µg) was purified (Endofree kit; QIAGEN, CA, USA) and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). In the tetracycline-regulated system,24 HCV core was expressed upon withdrawal of tetracycline and cells were expanded 48 h for expression.

ROS assay

Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1 supernatant (0.01 MOI) were exposed to the fluorescent ROS indicator 2,7-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) (Molecular Probes, CA, USA). Cell cultures were plated onto 24-well plates and treated with IFN and NAC at the time of infection. DCF was added (10 µM) to cultures for the last 30 min according to manufacturer’s protocol.25 Following incubation with DCF, cultures were washed and the ROS fluorescence was measured at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h of infection by metamorph and the mean pixel count was calculated from three or more independent experiments.

Estimation of 8-oxoG

Cells in chamber slides were washed with PBS, air-dried, fixed in (1:1) acetone-methanol and subsequently rehydrated in PBS for 15 min followed by sequential treatment with 100 µg/mL pepsin in 0.1 N HCl for 15–30 min at 37°C, 1.5 N HCl for 15 min and sodium borate for 5 min. After a final wash with PBS, cells were incubated with non-immune immunoglobulin G (0.1 µg/mL) (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA, USA) or anti-8-oxoG antibody (Trevigen; 1:200 dilution, MD, USA) for 30 min, washed with PBS Tween 20 and finally exposed to fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 30 min. Fluorescence was quantified by using confocal microscopy and metamorph software (CA, USA).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from uninfected or infected hepatoma cells and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a superscript II first-strand synthesis system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out with an ABI 7900 Real-time PCR System using the 18S gene as a reference.25 Three independent experiments were performed and standard deviations (SD) calculated.

DNA Strand Incision Assay for NEIL1

Nuclear extracts from HCV JFH-1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells at 48 and 72 h were prepared as described earlier25 and used in DNA strand incision activity with 32-P labeled 51-mer 8-oxoG containing bubble oligonucleotides (purchased from Midland, TX, USA) as described before.26 The intact (substrate) and cleaved oligonucleotides (product) were then separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis on 20% TBE–urea gels and radioactivity analyzed.

Tissue specimens

Liver biopsies from HCV-infected patients were obtained from the UWMC Hepatopathology Laboratory through a human subject approved protocol. Biopsies were snap frozen in ornithine carbamyl transferase (OCT) buffer for best preservation. Liver tissue specimens were divided into two groups: seven biopsies from liver explants of HCV-infected patients and 10 biopsies from noninfected transplants with no liver disease. Liver biopsies were reviewed by a single pathologist and stage was assigned according to the system described by Batts and Ludwig.27 Total RNA was extracted from sections of the liver biopsies by using the Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and NEIL1 RNA was quantitated by real time RT-PCR.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, including pixel count for ROS measurements, densitometric scans of western blots, RT-PCR analysis and radioactive enzyme activity assays, results were calculated as the means (±SD) of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way anova for comparisons of multiple groups. P ≤ 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant. All statistical tests were done using SigmaStat software (Jandel Scientific, CA, USA).

Results

HCV infection induced ROS, DNA damage and altered DNA glycosylase expression

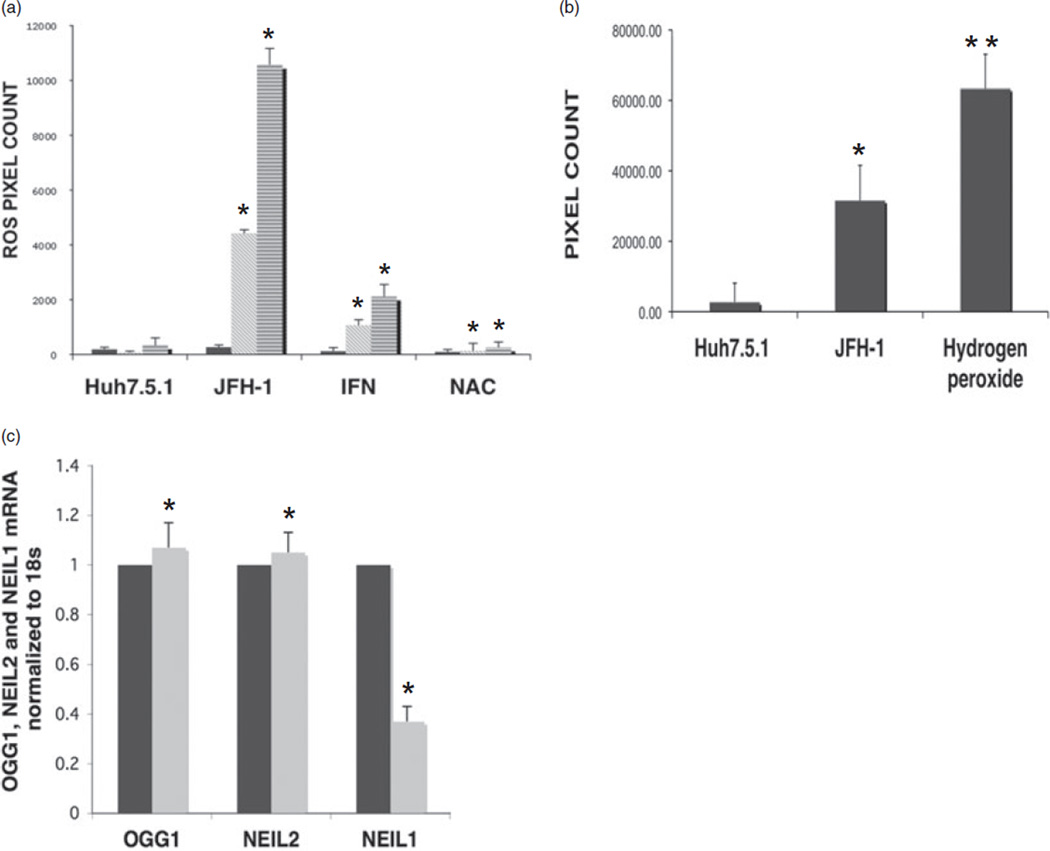

Here, we have analyzed oxidative stress generated in the form of ROS, oxidative DNA damage and the level of oxidative DNA repair enzymes in the setting of HCV infection. Production of ROS was measured by using a cell-based fluorescent dye that emits green fluorescence upon its oxidation in HCV JFH-1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells at 24-, 48- and 72-h time points. DCF fluorescence measured as pixel count showed a 32.2-fold increase in ROS in HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells at 48 h post-infection (Fig. 1a) compared to mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells. Induction of ROS in HCV JFH-1-infected cells reached its peak at 72 h post-infection with a 66-fold increase in pixel count. HCV infection and ROS generation did not affect cell viability as judged by the rate of cell growth at 48 and 72 h (data not shown). HCV-infected cells treated with IFN at the time of infection showed 6.5- and 16-fold increase in ROS at 48 and 72 h time points, respectively, compared to mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells. This was 4–5-fold less compared to HCV-infected cells not treated with IFN. Interestingly, treatment of HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells with the antioxidant NAC drastically reduced the ROS level which was comparable to mock-infected cells at all time points. The data show that HCV infection induced a high amount of ROS which can be partially or almost entirely removed by antiviral or antioxidant therapies, respectively.

Figure 1.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection induces reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA damage and alters DNA glycosylase expression. (a) From left to right: mock-infected, JFH-1 HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells (0.01 MOI), HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells treated with interferon (IFN; 100 U/mL) and N-acetyl cystein (NAC; 10 µM). ROS fluorescence was quantified at 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection by metamorph and expressed as pixel count. (b) Huh7.5.1 cells, Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1 for 72 h and Huh7.5.1 cells treated with 500 µM of H2O2 for 15 min on ice. 8-Oxoguanine (8-oxoG) antibody fluorescence was quantified by metamorph and expressed as pixel count. (c) Quantification of OGG1, NEIL2 and NEIL1 mRNA from mock- and JFH-1 HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells at 72 h post-infection by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.  , HUH7.5.1;

, HUH7.5.1;  , JFH-1.

, JFH-1.

Reactive oxygen species generated as a consequence of HCV infection could produce numerous DNA base modifications. Here, we examined 8-oxoG as a marker of oxidized DNA base in ROS-induced DNA damage. 8-oxoG formation was measured by immunofluorescence assay using a specific antibody to 8-oxoG in Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1 (0.01 MOI) at 72 h postinfection. As shown in Figure 1(b), infection of Huh7.5.1 cells with JFH-1 virus lead to strong nuclear staining of oxidized DNA 8-oxoG at 72 h post-infection with a sixfold increase in pixel count compared to mock-infected cells. Huh7.5.1 cells treated with 100 µM hydrogen peroxide served as positive control. This data indicated that ROS produced during HCV infection generated oxidized DNA bases, a hallmark of DNA damage.

To explore the effects of ROS-induced DNA damage on the oxidative repair pathway, we analyzed the expression of lesionspecific BER enzymes during HCV infection. Three major human DNA glycosylases, NEIL1, NEIL2 and OGG1 transcript levels, were quantified from HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells at 72 h post-infection by real time RT-PCR. We observed a significant 2.7-fold decrease in NEIL1 RNA in Huh7.5.1 cells infected with JFH-1 at 72 h post-infection with little or no change in NEIL2 and OGG1 RNA levels (Fig. 1c). The results indicated that the expression of the BER enzyme NEIL1 is downregulated in the context of 30–60-fold increase in ROS generation during HCV infection. Downregulation of NEIL1 was also observed in Huh7 cells containing a HCV full-length replicon (data not shown). It is to be mentioned that NEIL1 repression was not due to any growth inhibition as cells reach confluence (> 72 h), because mock-infected cells did not exhibit any alteration of NEIL1 (Fig. 1c). This finding was of high importance as it specifically demonstrated the specific involvement of cellular repair machinery heralded by the DNA glycosylase NEIL1 in a HCV setting and not OGG1 and/or NEIL2.

Alteration of NEIL1 expression and activity in HCV-infected cells

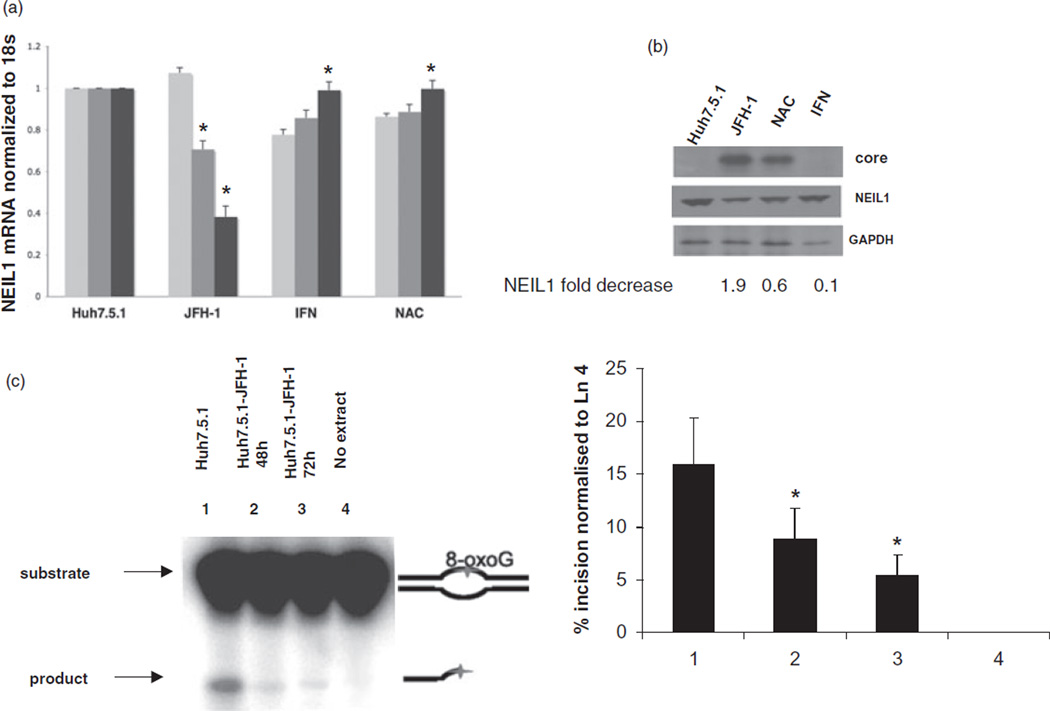

We then analyzed NEIL1 repression kinetics during HCV infection and investigated whether IFN and NAC had any effects on NEIL1. NEIL1 mRNA was measured in Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1 clone and treated with or without IFN and NAC separately by real-time RT-PCR at 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection. The NEIL1 transcript level was decreased by 1.5–2.8-fold after 48 and 72 h of JFH infection, respectively (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, treatment with the antioxidant NAC at the time of infection significantly diminished the NEIL1 repression indicating direct involvement of ROS generated after HCV-JFH-1 infection. Also, HCV-infected cells treated with the antiviral IFN at the time of infection showed restoration of the NEIL1 message. The antioxidant NAC did not impact the HCV JFH-1 infection of Huh7.5.1 cells (data not shown). These results indicated that impairment of NEIL1 was restored when: (i) HCV replication is inhibited by IFN; and (ii) HCV-induced ROS was removed by the antioxidant NAC.

Figure 2.

Alteration of NEIL1 expression and activity in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected cells. (a) Quantification of NEIL1 mRNA at 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR), normalized to endogenous 18-S RNA; mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells, Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1, HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells treated with interferon (IFN; 100 U/mL) and N-acetyl cystein (NAC; 10 µM), respectively, at the time of infection.  , 24 h;

, 24 h;  , 48 h;

, 48 h;  , 72 h. (b) Left to right lanes: total cell extracts were isolated from mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells, Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1, HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells treated with IFN (100 U/mL) and N-acetyl cystein (NAC; 10 µM) at the time of infection, separated by sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and levels of HCV core (top bands), NEIL1 (middle bands) and control glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) proteins (lower bands) were detected by western blot analysis. Densitometric scan shows NEIL1 fold decrease. (c) Impaired strand incision activity of NEIL1 DNA glycosylase. 32-P labeled 51-mer 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) containing bubble oligonucleotides was used as substrate. Lanes 1 and 4, cellular extracts of mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells and no extract, respectively; lanes 2 and 3, cellular extracts of Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1 at 48 and 72 h, respectively. In all cases, graphical representation of the NEIL1-specific incision or cleavage product percentage normalized to Lane 4 (no extract reaction) is depicted, showing averages of three experiments. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001).

, 72 h. (b) Left to right lanes: total cell extracts were isolated from mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells, Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1, HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells treated with IFN (100 U/mL) and N-acetyl cystein (NAC; 10 µM) at the time of infection, separated by sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and levels of HCV core (top bands), NEIL1 (middle bands) and control glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) proteins (lower bands) were detected by western blot analysis. Densitometric scan shows NEIL1 fold decrease. (c) Impaired strand incision activity of NEIL1 DNA glycosylase. 32-P labeled 51-mer 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) containing bubble oligonucleotides was used as substrate. Lanes 1 and 4, cellular extracts of mock-infected Huh7.5.1 cells and no extract, respectively; lanes 2 and 3, cellular extracts of Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV JFH-1 at 48 and 72 h, respectively. In all cases, graphical representation of the NEIL1-specific incision or cleavage product percentage normalized to Lane 4 (no extract reaction) is depicted, showing averages of three experiments. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001).

Next, we determined whether the HCV-induced reduction in NEIL1 mRNA conferred a reduction in NEIL1 protein expression. NEIL1 protein levels in JFH-1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells treated with and without IFN and NAC was determined at 72 h post-infection and was compared to mock-infected cells. Western blot analysis of the total cell lysate was performed with NEIL1 antibodies (ABcam Inc, MA, USA). Data showed decrease in NEIL1 protein in JFH-1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 2c). Importantly, NAC and IFN treatment restored NEIL1 protein levels. This data confirmed that the downregulation of NEIL1 transcript levels in HCV-infected cells extended to a repression of NEIL1 protein expression. Moreover, NEIL1 protein expression was restored by either blocking HCV replication or inhibiting HCV-induced oxidative stress.

We tested DNA glycosylase activity in the cellular extract of HCV JFH-1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells using bubble DNA oligonucleotides containing 8-oxoG as the oxidatively-modified base. Reduced damaged base incision was observed in JFH-1-infected cells at 48 as well as 72 h compared to uninfected cells (Fig. 2c). Because only the NEIL among glycosylases were capable of removing damaged base from bubble substrates,26 and NEIL1 and not NEIL2 levels were altered by HCV infection, we could conclude that JFH-1 infection resulted in impairment of NEIL1 activity.

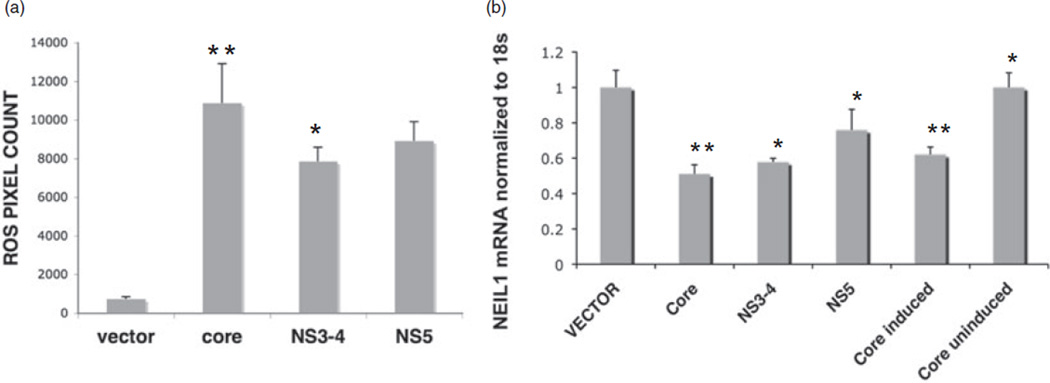

HCV component/s responsible for ROS generation and NEIL1 downregulation

We next investigated the role of key HCV structural and NS genes in ROS induction. The HCV genes, namely, core, NS3-4 and NS5A, were expressed in Huh7.5.1 cells and ROS generation was measured 72 h post-transfection. Increase in ROS-associated fluorescence by HCV core, NS5A and NS3-4 genes was compared to the transfected empty vector control, pcDNA3.1 (Fig. 3a). Core showed an approximately 14-fold increase in ROS whereas NS3-4 and NS5A genes showed 10.6- and 12.1-fold increase in ROS level. This data suggested involvement of more than one HCV gene in ROS induction which is in accordance with previous findings8 with HCV core standing out as one of the crucial players.

Figure 3.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) component/s responsible for reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and NEIL1 downregulation. (a) Induction of ROS by HCV structural and non-structural genes. Huh7.5.1 cells transfected with empty vector plasmid and plasmids expressing core, NS3-4 and NS5A genes as described in Methods. Cells were treated with 5 µM of 2,7-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) at 72 h post-transfection and ROS fluorescence quantified by metamorph. (b) Decrease in NEIL1 transcript by HCV structural and non-structural genes. Huh7.5.1 cells stably transfected with core under tet-regulated promoter and transiently transfected with empty vector as well as plasmids expressing core, NS3-4 and NS5A genes, respectively. Quantification of NEIL1 mRNA by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction at 72 h post-transfection (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001).

Hepatitis C virus structural and NS genes implicated in ROS generation, were further analyzed for modulating NEIL1 expression. Individual HCV genes core, NS3-4a, NS5A and empty vector pcDNA 3.1 were transiently transfected in Huh7.5.1 cells and protein expression of the transfected genes was monitored by western blot and immunofluorescence experiments at 24, 48 and 72 h post-transfection (data not shown). NEIL1 RNA level was determined by real time RT-PCR at 72 h post-transfection. Cells expressing core showed an approximately twofold decrease in NEIL1 RNA compared to vector transfected control whereas NS3-4a transfection demonstrated 1.7-fold repression followed by NS5A causing the least repression in NEIL1 mRNA compared to NS3-4a and core genes (Fig. 3b). Also, in another hepatoma cell line, tet-regulated HeLa cells expressing the core gene,24 a similar pattern of NEIL1 mRNA inhibition was observed in the presence of tetracycline with core induction; whereas in the absence of the tetracycline, NEIL1 expression was not altered from its basal level. Although, HeLa and Huh7.5.1 cell lines have different gene expression profiles, yet HCV core expression could modulate the NEIL1 expression in both. This data demonstrated that HCV genes responsible for ROS induction, primarily the HCV core, was also responsible for transcriptional repression of NEIL1. The transcriptional regulation of NEIL1 by HCV genes was also apparent from reduction in its promoter-luciferase activity, where core was again found to be the most active component (data not shown).

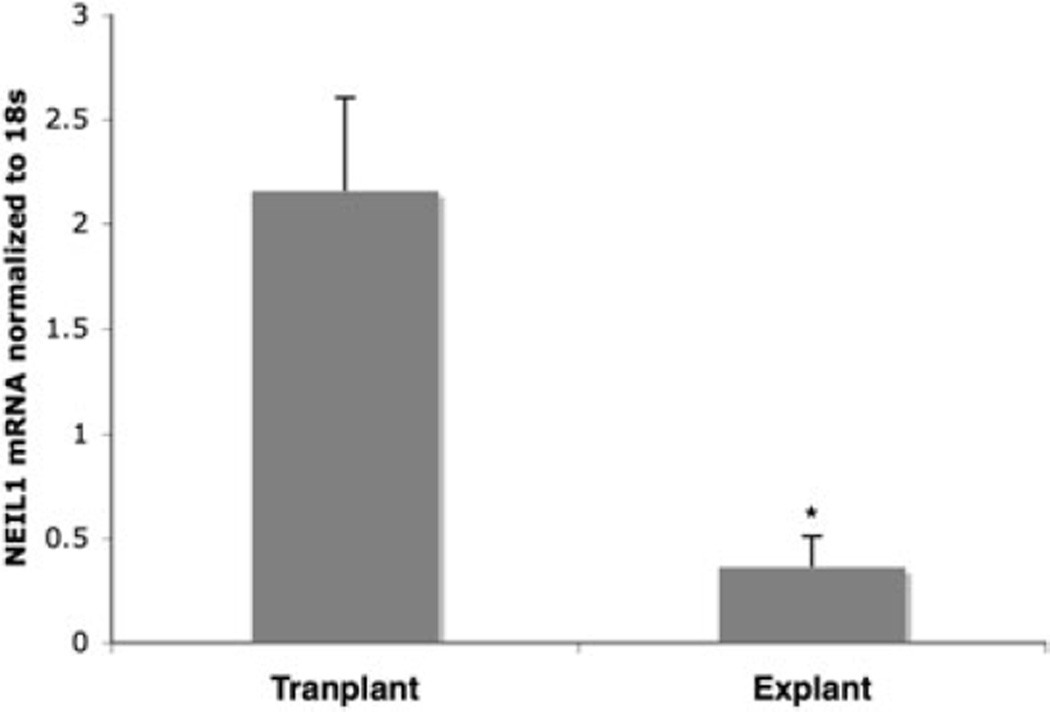

Association of NEIL1 repression with disease in HCV-infected human liver tissues

To correlate our in vitro findings to the in vivo situation, we analyzed NEIL1 mRNA expression in HCV genotype 1-infected seven liver explant tissues, classified as having cirrhosis and 10 biopsies from non-infected liver transplant. Explant liver specimens with severe disease showed 5.9-fold decreased NEIL1 mRNA expression compared to normal liver tissues (Fig. 4). This showed that during HCV infection NEIL1 mRNA level was heavily reduced in liver with severe disease and that was comparable to our in vitro study.

Figure 4.

Quantitation of NEIL-1 mRNA in human liver biopsies infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. NEIL1 RNA was quantitated from biopsies of seven liver explants of HCV-infected patients and 10 non-infected transplants with no liver disease. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001).

Discussion

While the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C remains undefined, both morbidity and mortality related to this indolent yet highly prevalent disease are increasing at an alarming rate. Several studies report that enhanced oxidative stress in HCV infection may have a pathogenic role in disease progression.28 An important pathophysiological consequence of increased oxidative stress is endogenous DNA damage, and the base excision repair pathway is the most important mechanism to withstand such lethal effects.

In the current report, we show for the first time that HCV infection triggers heavy ROS production in a time-dependent manner. Oxidatively modified DNA base 8-oxoG was detected in HCV-infected cells. To elucidate the role of DNA base excision repair in this context, we analyzed the lesion removing BER enzymes NEIL1, NEIL2 and OGG1. Of these, NEIL1 was found to be significantly repressed and with impaired activity in HCV-infected cells with no major alteration of other DNA glycosylases. However, we earlier reported transcriptional upregulation of NEIL1 levels in colon carcinoma cells (HCT116) treated with the ROS-producing reagent, glucose oxidase.25 We offer two possible explanations for why NEIL1 might be paradoxically downregulated during HCV infection even though ROS is elevated. The first possibility is that HCV replication produces very high levels of ROS (> 30-fold) and extensive DNA damage which surpass the threshold in feedback regulation of DNA repair, and eventually lead to impairment of NEIL1 expression and further reduction in DNA repair activity. A second possibility is direct inhibition of NEIL1 gene expression by one or more of the HCV gene products. This is possible, especially when one considers the wide range of examples where HCV gene products are already known to interfere with host gene expression and/or function.29 Our data are in accordance with the view that core and NS5A induce extensive ROS,8 moreover it shows that individual HCV genes core, NS3-4 and NS5A downregulate NEIL1 with core showing the maximal effect. Core exerted similar pattern of NEIL1 repression in two different cell lines with Huh7.5.1 cells expressing core by transient transfection, and Hela cells expressing core under tetracycline regulation.

Finally, liver biopsy specimens of patients infected with hepatitis C with severe liver disease demonstrated major decrease in NEIL1 RNA expression compared to cases with no disease. A bigger study group with biopsies at different time points of HCV infection is required to correlate the NEIL1 expression kinetics with HCV infection-induced liver pathogenesis.

Our findings gained support from a report by Shinmura et al.30 that NEIL1 was downregulated and mutated in six of 13 tissue specimens from patients with gastric cancer. Recently, it was reported that NEIL1 downregulation increased spontaneous mutation and the mutant frequency was further enhanced under oxidative stress.31 Previous studies have shown that knockdown of NEIL1 results in sensitization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts to ionizing radiation.32 NEIL1 knockout (Neil1−/−) mice accumulate mitochondrial DNA damage and develop fatty liver disease.33 NEIL1 thus plays a distinct and important role in repairing endogenous and induced mutagenic oxidized bases in mammals. Ours is the first report that suggests that a major cellular protective response mediated by the oxidative damage-specific enzyme, NEIL1 is seriously impaired during HCV-induced inflammation both in vitro and ex vivo.

We hypothesized that inhibition of viral replication by IFN might cause reversal of acute oxidative stress thereby restoring any impaired DNA repair. Indeed, analysis of ROS and NEIL1 expression in IFN-treated HCV-infected Huh7.5.1 cells confirmed a reduction in ROS and partial restoration of NEIL1 expression. Interestingly, the antioxidant, NAC significantly inhibited ROS generation and more efficiently restored NEIL1 levels in HCV-infected cells.

Antioxidants are reported as potential alternative medicines or combination drug against HCV in the Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-Term Treatment Against Cirrhosis (HALT-C) Trial,34,35 and NAC has the capability to modulate in a protective sense a broad variety of mechanisms involved in DNA damage and carcinogenesis, and therefore has the potential to prevent cancer and other mutation-related diseases.36

Our findings that NAC and IFN remove ROS and restore normal levels of NEIL1 in HCV-infected cells agree with these previous observations, reinforcing the prospects of antioxidant and antiviral combination therapy.

Taken together, our results provide a novel insight into HCV pathogenesis with emphasis on oxidative damage and aberrant host repair associated with chronic HCV infections. Activation of oxidative base removal and repair mechanisms contributes to the protection of tissues against ROS-induced cytotoxicity and impairment of NEIL1 expression serves as a concomitant consequence as well as a potential cause of persistent HCV infection. We hypothesize that overexpression of NEIL1 in HCV-infected cells may protect injured liver cells from the deleterious effects of ROS and provide new avenues for targeted therapy for patients with chronic HCV infection and progressive liver disease.

References

- 1.Davis GL, Albright JE, Cook SF, Rosenberg DM. Projecting future complications of chronic hepatitis C in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:331–338. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grakoui A, Wychowski C, Lin C, Feinstone SM, Rice CM. Expression and identification of hepatitis C virus polyprotein cleavage products. J. Virol. 1993;67:1385–1395. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1385-1395.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohmann V, Koch JO, Bartenschlager R. Processing pathways of the hepatitis C virus proteins. J. Hepatol. 1996;24:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal S, Shuhart MC, Thomassen L, et al. Intrahepatic hepatitis C virus replication correlates with chronic hepatitis C disease severity in vivo. J. Virol. 2006;80:2280–2290. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2280-2290.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machida K, Cheng KT, Lai CK, Jeng KS, Sung VM, Lai MM. Hepatitis C virus triggers mitochondrial permeability transition with production of reactive oxygen species, leading to DNA damage and STAT3 activation. J. Virol. 2006;80:7199–7207. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00321-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang T, Weinman SA. Causes and consequences of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in hepatitis C. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl. 3):S34–S37. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Boehning DF, Qian T, Popov VL, Weinman SA. Hepatitis C virus core protein increases mitochondrial ROS production by stimulation of Ca2+ uniporter activity. FASEB J. 2007;21:2474–2485. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7345com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Mediavilla MV, Sanchez-Campos S, Gonzalez-Perez P, et al. Differential contribution of hepatitis C virus NS5A and core proteins to the induction of oxidative and nitrosative stress in human hepatocyte-derived cells. J. Hepatol. 2005;43:606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zekri AR, Sabry GM, Bahnassy AA, Shalaby KA, Abdel-Wahabh SA, Zakaria S. Mismatch repair genes (hMLH1, hPMS1, hPMS2, GTBP/hMSH6, hMSH2) in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3020–3026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Pelt JF, Severi T, Crabbe T, et al. Expression of hepatitis C virus core protein impairs DNA repair in human hepatoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2004;209:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aukrust P, Luna L, Ueland T, et al. Impaired base excision repair and accumulation of oxidative base lesions in CD4+ T cells of HIV-infected patients. Blood. 2005;105:4730–4735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demple B, Harrison L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994;63:915–948. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasai H, Crain PF, Kuchino Y, Nishimura S, Ootsuyama A, Tanooka H. Formation of 8-hydroxyguanine moiety in cellular DNA by agents producing oxygen radicals and evidence for its repair. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:1849–1851. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.11.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner JR, Hu CC, Ames BN. Endogenous oxidative damage of deoxycytidine in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:3380–3384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krokan HE, Standal R, Slupphaug G. DNA glycosylases in the base excision repair of DNA. Biochem. J. 1997;325(Pt 1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3250001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedberg EC, Aguilera A, Gellert M, et al. DNA repair: from molecular mechanism to human disease. DNA Repair. 2006;5:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazra TK, Das A, Das S, Choudhury S, Kow YW, Roy R. Oxidative DNA damage repair in mammalian cells: a new perspective. DNA Repair. 2007;6:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazra TK, Izumi T, Boldogh I, et al. Identification and characterization of a human DNA glycosylase for repair of modified bases in oxidatively damaged DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3523–3528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062053799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klungland A, Rosewell I, Hollenbach S, et al. Accumulation of premutagenic DNA lesions in mice defective in removal of oxidative base damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:13300–13305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minowa O, Arai T, Hirano M, et al. Mmh/Ogg1 gene inactivation results in accumulation of 8-hydroxyguanine in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4156–4161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050404497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takao M, Kanno S, Kobayashi K, et al. A back-up glycosylase in Nth1 knock-out mice is a functional Nei (endonuclease VIII) homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:42205–42213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 2005;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polyak SJ, Khabar KS, Paschal DM, et al. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein induces interleukin-8, leading to partial inhibition of the interferon-induced antiviral response. J. Virol. 2001;75:6095–6106. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6095-6106.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller K, McArdle S, Gale MJ, Jr, et al. Effects of the hepatitis C virus core protein on innate cellular defense pathways. J. Interferon. Cytokine. Res. 2004;24:391–402. doi: 10.1089/1079990041535647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das A, Hazra TK, Boldogh I, Mitra S, Bhakat KK. Induction of the human oxidized base-specific DNA glycosylase NEIL1 by reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35272–35280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das A, Boldogh I, Lee JW, et al. The human we rner syndrome protein stimulates repair of oxidative DNA base damage by the DNA glycosylase Neil1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:26591–26602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis. An update on terminology and reporting. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1995;19:1409–1417. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003;17:1195–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gale M, Jr, Foy EM. Evasion of intracellular host defence by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;436:939–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shinmura K, Tao H, Goto M, et al. Inactivating mutations of the human base excision repair gene NEIL1 in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2311–2317. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maiti AK, Boldogh I, Spratt H, Mitra S, Hazra TK. Mutator phenotype of mammalian cells due to deficiency of NEIL1 DNA glycosylase, an oxidized base-specific repair enzyme. DNA Repair. 2008;7:1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenquist TA, Zaika E, Fernandes AS, Zharkov DO, Miller H, Grollman AP. The novel DNA glycosylase, NEIL1, protects mammalian cells from radiation-mediated cell death. DNA Repair. (Amst) 2003;2:581–591. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vartanian V, Lowell B, Minko IG, et al. The metabolic syndrome resulting from a knockout of the NEIL1 DNA glycosylase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1864–1869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507444103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houglum K, Venkataramani A, Lyche K, Chojkier M. A pilot study of the effects of d-alpha-tocopherol on hepatic stellate cell activation in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1069–1073. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seeff LB, Curto TM, Szabo G, et al. HALT-C Trial Group. Herbal product use by persons enrolled in the hepatitis C Antiviral Long-Term Treatment Against Cirrhosis (HALT-C) Trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:605–612. doi: 10.1002/hep.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flora DS, Izzotti A, D’Agostini F, Balansky RM. Mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine in the prevention of DNA damage and cancer, with special reference to smoking-related end-points. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:999–1013. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.7.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]