Abstract

Background

Primary care is the most promising venue for the management of late-life depression in China. The current study was designed to establish the prevalence of major depressive disorder among older adults in primary care, and to examine the correlates, and the natural course of late-life depression over a year.

Methods

A sample of 1275 adults aged over 60 years was recruited from a primary care clinic in urban China for screening with PHQ-9, and 262 participants stratified by PHQ-9 score were interviewed to collect the presence of major depressive disorder (MDD), the availability of social support, and physical health and functional status. Participants were followed up for 12 months at 3-month intervals.

Results

The estimated prevalence of MDD was 11.3% with the SCID interview. Increasing age, female gender, and lower educational level, living alone, low support from family, high medical illness burden, and impairment of daily function were significantly associated with MDD in later life. Less than 1% of these patients received treatments. More than 60% of patients with MDD at baseline remained depressed throughout the 12 month follow-up period; and only 3 patients had been treated during the 12-month follow-up.

Limitations

The correlates of late-life depression observed here may not necessarily serve as risk factors guiding the development of future prevention strategies.

Discussion

In an urban Chinese primary care setting, late-life depression was found to be a common condition. Few patients with MDD received treatment for their condition, and the majority remained depressed over the following year.

Keywords: Late-life depression, Chinese primary care, Prevalence, Correlates, Natural course

1. Introduction

Depression is a common disorder in later life, and is often complicated by comorbid physical illness, functional disability, and suicide risk. It is also associated with increased utilization of health-care services (Beekman et al., 1997). The prevalence of clinically significant depression in late life has been estimated to range from 3% to 30% worldwide (Blazer, 2003; Papadopoulos et al., 2005). As in other countries, depression is a major public health issue in China. In Chinese older adults, rates of depression have ranged from 4% to 19.5% (Gao et al., 2009; Lai, 2004; Ma et al., 2008; Yeung et al., 2004).

The population of older adults in China is rapidly increasing. In 2010 there were an estimated 177 million people aged 60 years and over in China. By 2020 that number is projected to rise to over 400 million (China Municipal Committee for Aging People, 2011). As the size of the older adult population in China rises, so too will the number of people suffering from age-associated mental illnesses.

Although affective illness is a treatable condition using both pharmacological and psychosocial approaches, depression in older adults often goes undiagnosed and inadequately treated. Recent studies have underscored the special challenges to effective management of mood disorders at the patient, provider, and service system levels. A shortage of mental health professionals, the paucity of community-based mental health services, and the stigma attached to mental illnesses are the main barriers mitigating against access to specialty mental healthcare in China. There are now approximately 17,000 psychiatrists, to deal with an estimated 100 million people suffering from mental illnesses (The Economist, 2007). Phillips et al. (2009) showed that among individuals with a diagnosable mental illness in China, only 8% had ever sought professional help, and 5% had ever seen a mental health professional. Although a community mental health system is developing in some large cities such as Shanghai, Hangzhou and Beijing, its focus is on select neuropsychiatric disorders such as psychosis, mental retardation, and seizure disorders (Park, 2005). Hangzhou, for example, is a city of 4.19 million people (Hangzhou Government, 2009) where, in 2008, there were about 300,000 outpatient visits to outpatient mental health clinics, primarily by younger or middle aged adults with chronic neuropsychiatric disorders.

Like in the West, mental illness is stigmatized in China, especially among older adults, who are even less likely to seek out mental health care (Garrard et al., 1998). Instead, they receive care in community-based primary care clinics where the providers have little or no education about the detection, diagnosis and management of mental disorders in any age group. Fortunately there is increasing focus on improving the quality of depression management in primary care clinics in China. In 2006 the central government in China adopted policies to encourage the adoption of chronic disease management and treatment principles by primary care providers (Wang et al., 2007a). Depression is a chronic recurrent illness the management of which is well-suited to the primary care setting, in particular those geared for older adults. In these settings, collaborative care management strategies for depression have been shown to be effective in a number of controlled trials in the West (Katon et al., 2010; Unutzer et al., 2002). To date, however, no studies of the prevalence, correlates, or natural history of depression in older patients in Chinese primary care clinics have been conducted, and neither have there been any trials of primary care-based interventions for the illness in China.

This study is the foundation for a program designed to integrate mental health care into the Chinese primary care delivery system. The aims of present study were to: (1) estimate the prevalence of late-life depression among adults over 60 years of age in Chinese urban primary care clinics in the city of Hangzhou; (2) examine correlates of late-life depression in Chinese primary care clinic patients; and, (3) describe the course of depression in a cohort of Chinese primary care patients aged 60 years or older over a period of 12 months.

2. Method

2.1. Research site and participants

The Primary Care Late-life Depression Study (PC-LDS) is a naturalistic, longitudinal study of late-life depression in Chinese primary care. It is a collaborative project between the Department of Psychology of Zhejiang University and the Health Department of Shangcheng District of Hangzhou City, China. The study site is a primary care clinic in the Shangcheng District of Hangzhou funded by the local government and staffed by two primary care physicians (PCPs) and three nurses. Typical of primary care clinics in China (Wang et al., 2007b), the study site provides a broad range of services, including preventive visits, health education and promotion, birth control, outpatient evaluation, management of common illnesses, case management of chronic disease, and physical rehabilitation.

When data collection began in January 2009, the clinic served 8394 local residents, of whom 1787 were aged ≥ 60 years. Criteria for inclusion to the study were: (1) age ≥ 60 years; (2) residence in the neighborhood served by the primary care clinic (and hence registered as a patient of the clinic); (3) ability to communicate orally; and, (4) capacity to provide informed consent. People with significant cognitive deficits were ineligible to participate.

3. Measures

3.1. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Chinese version

The Chinese version of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) is designed to diagnose a current episode of major depressive disorder (MDD). The interview protocol has been shown to yield reliable and valid diagnostic data in China (Phillips et al., 2009). The SCID interviews were performed by two psychiatrists who demonstrated high inter-rater reliability for mood disorders (kappa=.81).

3.2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The Chinese version of PHQ-9 was used to measure participants’ depressive symptoms. The psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the PHQ-9 have been examined with older Chinese primary care patients (Chen et al., 2010). Scores demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.91) and evidence of validity was supported by high levels of sensitivity and specificity in the detection of Major Depressive Episodes using a cut-off of 10 or more (Chen et al., 2010).

3.3. Physical illness burden

The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) (Linn et al., 1968) is a measure of medical burden (excluding psychiatric disorders). The CIRS total score was used to assess participants’ medical health status. We translated the CIRS for use in this study and, in preliminary research, we found an inter-rater reliability of 0.95 (unpublished data).

3.4. Daily life function

The Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (IADL) (1988) was used to assess higher order functioning (e.g., food preparation, housekeeping, and managing finances). The Chinese version of the IADL scale has been validated in Hong Kong, and shown to be reliable for assessing an older person’s ability to live independently in the community (Tong and Man, 2002).

3.5. Social support from family

We used living status and the family social support items in the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) to measure participants’ family support. The Chinese version of the LSNS has been validated in Hong Kong (Chi et al., 2001). In this study, the measurement of family social support consists of 6 questions, item scores range from 0 to 5, and the total score is 30. For the living status 2 options were included: living alone, or living with somebody (including family members and relations).

4. Procedures

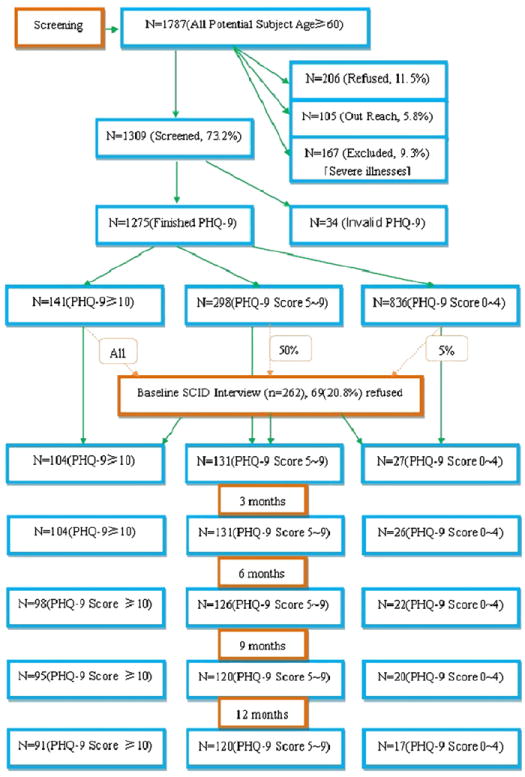

Of 1787 potentially eligible participants, 139 residents could not be located, 206 refused, and 167 residents were excluded because they were hospitalized, had serious cognitive impairment, or were too frail to participate. Finally, 1275 (71%) residents in this neighborhood were recruited in this study during a 6-month period from 1 January to 30 June 2009 (see Fig. 1). Subjects were interviewed by psychiatrists in the waiting room of the primary care clinic after they received a complete description of this study and provided written informed consent, according to procedures approved by the Human Study Committee of Zhejiang University.

Fig. 1.

Survey profile.

The 1275 participants were first screened with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) at the PCC. Second, all participants with PHQ-9 scores≥10 were invited to participate in the next stage of the study, which involved a face-to-face interview with a psychiatrist. In addition, 50% of participants with PHQ-9 scores in the 5–9 range were randomly selected to receive the second stage interview, along with 5% of those with PHQ-9 total scores of 0–4. The interviews were conducted 1 week following the PHQ-9 screening. Of those invited to participate in the interview, 20% refused (n=69 out of 331), thus providing a sample of 262 participants who completed the interview protocol (see Fig. 1).

All participants with the initial SCID-interview (n=262) were invited to complete telephone follow-ups at 3, 6, and 9 months (PHQ-9 and SF-12), as well as a final face-to-face interview after 12 months with SCID, PHQ-9 and SF-12. The SCID-interview at the initial and 12-month follow-up was implemented by two psychiatrists (introduced in the SCID measure). One research assistant (a psychiatric nurse) did the telephone follow-up at 3, 6, and 9 months after she was trained to use the PHQ-9 and SF-12 measure via the telephone. The two psychiatrists did the quality control via their telephone follow-up on 5 subjects at 3, 6, and 9 months respectively. Of the 262 subjects initially included in the study, 34 participants (12.9%) dropped out at 12 months follow-up. The final follow-up group consisted of 228 participants (see Fig. 1).

5. Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of subjects. Current prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) was estimated using two methods: first, as the proportion of subjects in the entire sample who scored above a standard cut-off of ≥10 on the PHQ-9, the level shown to be associated with major depression at optimal sensitivity and specificity (Chen et al., 2010). Second, we calculated prevalence using the subset of patients found on the SCID to have a diagnosis of MDD, because the SCID as the gold standard for diagnosis helps place the depression symptom severity measure into a more precise clinical perspective. To do so we used sampling weights based on selection of these subjects from the entire group, which is the reciprocal of the above selection probability, to remove verification bias when calculating the prevalence rate by this method.

For the correlates of MDD in the primary care setting, we also conducted logistic regression to examine the association between MDD and the hypothesized predictors. First we conducted a series of univariate logistic regressions on MDD for each potential predictor. Then, all variables significant at p<0.05 level were entered into a multiple logistic regression model to examine the independent association of each variable with MDD diagnosis. The result is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlates of late-life MDD based on multivariate logistic regression (n=262).

| Category or increment | Coefficient | Standard error | P | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | Male | Reference | ||||

| Female | 0.693 | 0.393 | 0.043* | 2.01 | 0.93–4.32 | |

| Education level | 5 years or less | 1.012 | 0.329 | 0.002** | 0.36 | 0.21–0.79 |

| 5 years or more | Reference | |||||

| Social support | ||||||

| Living status | Alone | 0.551 | 0.373 | 0.035* | 0.57 | 0.68–1.68 |

| With someone | Reference | |||||

| Health status | ||||||

| CIRS | High level (9 point more) | 2.069 | 0.320 | <0.001** | 7.92 | 4.23–14.82 |

| Low level (8 point less) | Reference | |||||

| IADL | Impaired | 0.851 | 0.308 | 0.006** | 2.34 | 1.28–4.28 |

| Non-impaired | Reference | |||||

To examine changes in depression severity over time as a function of initial baseline severity, we plotted mean PHQ-9 scores and conducted a repeated measures ANOVA (adjusting for age and gender) over the 12-months separately for each baseline severity group as defined by the PHQ-9 score (i.e., low=0–4, mild=5–9, and high≥10). To follow-up this effect, we examined two specific interaction contrasts to test whether the difference between baseline measures and those obtained at the 12-month follow-up differed between the high versus low baseline symptom severity groups and the high versus medium groups.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 16 software.

6. Results

6.1. Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1 separately for the entire sample and for the sub-sample who completed the SCID interview. The entire sample of 1275 had a mean age of 71.5 years with a standard deviation of 9.6 years. Out of this group, 785 (65%) were female, and 725 (57%) had 6 years or more of education. Among the SCID interview group, their mean age was 74.2 years, with a standard deviation of 8.4 years, 167 (64%) were female, and 124 (47%) had 6 years or more on education (see Table 1). Based on chart review of those who were interviewed (n=262), only three subjects (1.2%) received an MDD diagnosis, of which one patient took a 4 week course of antidepressants and the other two did not take any medicine for their depression. There were two persons with diagnoses of schizophrenia. No other subjects had either a mental disorder diagnosis or treatment with psychotropic medication or therapy recorded in their primary care medical record.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of screening and SCID interview group.

| Screening group (n=1275) | Interview group (n=262) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.5±9.6 (60–94) | 74.2±8.4(60–93) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 490 (38%) | 95 (36%) |

| Female | 785 (62%) | 167 (64%) |

| Education | ||

| No | 214 (16.8%) | 59 (22.6%) |

| 1–5 years | 336 (26.4%) | 79 (30.2%) |

| 6–8 years | 425 (33.3%) | 81 (30.9%) |

| 9–11 years | 188 (14.7%) | 36 (13.7%) |

| Over 12 years | 112 (8.8%) | 7 (2.6%) |

| Marriage | ||

| Married | 994 (78%) | 185 (70.6%) |

| Devoiced | 9 (0.7%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Widows | 265 (20.8%) | 73 (27.8%) |

| Single | 7 (0.5%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Living situation | ||

| With spouse | 632 (49.6%) | 131 (50%) |

| With children | 499 (39.1%) | 82 (31.3%) |

| With relatives | 20 (1.6%) | 6 (2.3%) |

| Alone | 124 (9.7%) | 43 (16.4%) |

| Occupation | ||

| Full-time | 28 (2.2%) | 6 (2.3%) |

| Part-time | 16 (1.3%) | 6 (2.3%) |

| Retired | 1231 (96.5%) | 250 (95.4%) |

6.2. Prevalence of MDD

Of 1275 subjects screened for depression, 141 participants had PHQ-9 scores≥10, an estimated point prevalence of 11.1% (95% CI=8.9–13.6). Among the 262 participants with SCID interview, 97 were found to meet the DSM-IV criteria for MDD. After sample weighting, the sample size for the prevalence calculation was 856, yielding an estimated point prevalence of MDD in this primary care sample of 11.3% (95% CI=9.3–15.7).

6.3. Correlates of late-life MDD in primary care

Table 2 presents the multivariate logistic regression model examining correlates of the presence (versus absence) of MDD among those interviewed with the SCID. Based on the binary logistic regression on MDD, the variables of gender (p=0.039), education (p=0.006), living status (p=0.03), IADL (p=0.02), and CIRS (p<0.001) were entered into the model (significant level p<0.05). Female gender and lower education were significantly associated with MDD diagnosis. According to the SCID interview results, the prevalence of MDD in women (n=72 with MDD) was higher than in men (n=25 with MDD) (8.4% vs. 2.9%), and the prevalence of MDD in those with 5 years of education or less was 8.6%, relative to 2.7% in the higher education group. The same results showed in the PHQ-9 scores, women vs. men (8.5% vs. 2.6%), and high vs. low education (2.9% vs. 8.2%). Regarding psychosocial factors, living alone was significantly associated with risk for depression. For the health status level, odds of depression increased as the CIRS amount of medical illness burden and the number of IADL deficits.

6.4. Course of late-life depression

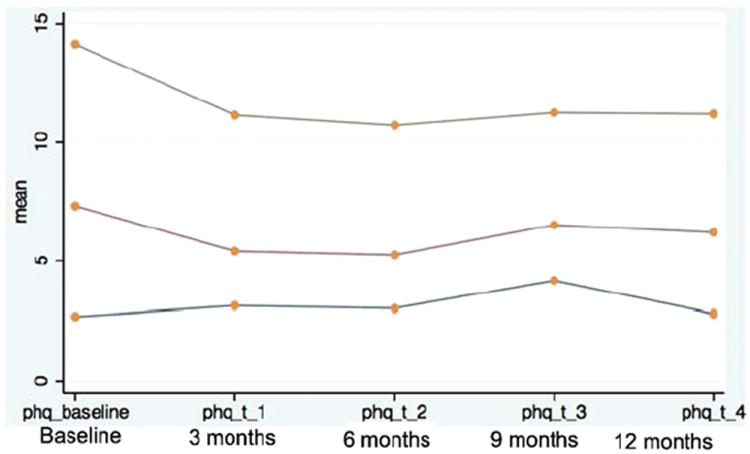

To examine the course of late-life depression, we plotted the PHQ-9 severity at each assessment point separately for each baseline severity group (i.e., PHQ score low, 0–4; mild, 5–9; high, 10+). The descriptive statistics in Fig. 2 suggest moderate change in the high baseline severity group (i.e., approximate 3 point drop in PHQ-9 score), with minimal to no change over time in the mild to low groups. A repeated measures ANOVA (adjusting for age and gender) is consistent with this interpretation, with a significant time by baseline group interaction indicating that change occurred in one (or more) group(s) [Greenhouse–Geisser corrected, F(6.343, 707.259)=5.255, p<0.001]. As would be expected based on visual inspection of mean differences in Fig. 2, after adjusting for age and gender, the magnitude of the drop in PHQ-9 severity evidenced for the high baseline severity group was significantly greater than the magnitude of change evidenced for the medium group (mean difference between high and medium=−1.855, p<.01) and low group (mean difference between high and low=−3.015, p<.01).

Fig. 2.

Unadjusted PHQ-9 means over time as a function of initial severity grouping.

Finally, we examined changes in MDD diagnosis among those interviewed with the SCID at baseline and again 12 months later. Ninety-seven had MDD at the outset of the study and 71 patients (73.2% of those with MDD at baseline) remained syndromally depressed a year later. For 228 participants who finished all follow-up measures, their PHQ-9 score at baseline, their SCID diagnosis at baseline, and 12-month later were listed in Table 3. At baseline, we found that one patient with MDD had received treatment with anti-depressants; and after the following year, only three patients (3.2%) with MDD had been treated by referral to mental health specialists.

Table 3.

Subjects in PHQ-9 and SCID grouping at baseline and 12-month follow-up.

| Baseline PHQ-9 | Baseline SCID | 12-month follow-up SCID |

|---|---|---|

| 0–4 (n=17) | MDD (n=0) | MDD (n=0) |

| 5–9 (n=120) | MDD (n=18) | MDD (n=21) |

| ≥10 (n=91) | MDD (n=73) | MDD (n=50) |

7. Discussion

We found the prevalence of major depression to be 11.3% among elders in this Chinese urban primary care clinic. Another recent study in rural elderly Chinese reported that 26.5% met the ICD-10 criteria for mild depression and 4.3% for severe depressive illness (Gao et al., 2009). A large survey conducted in seven regions of China in 1993 reported a point prevalence rate of 1.1% for MDD (Zhang et al., 1998); while other studies reported point prevalence rates of 1.7% to 6% (Demyttenaere et al., 2004; Phillips et al., 2009). The higher rate of MDD noted here may reflect methodological differences, regional variation, or more generalizable changes over time in reporting of depressive symptoms. The lower rates of depression often seen in China as compared to Western countries have been attributed to masked symptoms or a tendency to express depression somatically (Parker et al., 2001). As China undergoes rapid socioeconomic changes, however, culturally determined patterns of illness expression may also be in a state of flux, especially the present sample of elders who came from a relatively prosperous and rapidly changing urban area representing the leading edge of change.

The pattern of correlates of late-life depression that we observed was also similar to that seen in Western countries in which demographic and health-related characteristics, health service use, functional impairment, social activities, physical activity, and social support have been identified (Blazer, 2003; Chi and Chou, 2001; Chi et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2007; Phillips et al., 2009). In the present study, we found that female sex, lower education level, poor family support and high medical illness burden were associated with high risk of late-life depression in primary care settings. Before 1949, many women could not receive education equal to that of men in China. Many studies have identified that medical illness was associated with the presence of depression in late life (Bisschop et al., 2004; Chiu et al., 2005; Lyness et al., 2009). With older age, cumulative illness burden and functional impairments increase, both of which have been associated with depression in previous studies (Lenze et al., 2001; Oldehinkel et al., 2001), a pattern similar to that observed in the present study. The association between poor social support and current depression has been demonstrated in many studies around the world (Cui et al., 2008; Lyness et al., 2009; Travis et al., 2004).

With regard to the course of late life depression in this Chinese urban PCC, one year follow-up showed that 70% of patients with MDD remained depressed with scores on the PHQ-9 at 10 or higher. Older adults with less severe initial presentations (PHQ-9 total scores below 10) did not show reductions in severity over 1 year. Over 60% of them still had depressive symptoms with the 3-month follow-up on PHQ-9. These results suggest that prognosis of late life depression is poor in Chinese urban primary care under the current circumstances in which, as demonstrated in this sample, mental disorder diagnoses are rarely made and treatment is ordinarily not provided.

The high prevalence and poor prognosis of depression in older urban primary care patients indicate an urgent need for improvements in the quality of care they receive. At the service system level, recent changes in health policy by the Chinese central government (Wang et al., 2007a) provide an important opportunity to address that need by designating depression as one of the chronic diseases for which primary care providers must take management responsibility. As well, Chinese primary care is universal and is easily accessible for most urban residents. Residents can usually find a PC clinic within a half-mile radius of their homes. At the provider level, primary care clinicians in China have little training in mental health care. PCC providers’ knowledge and skills appear to underscore the recognition and appropriate management of depression (Williams et al., 1999). Therefore, improved education coupled with access by PCC clinicians to decision support tools concerning the diagnosis and treatment of depression is likely to be an important part of the solution. Of course, for those older adults with more complex psychiatric illness, easy access to consultations by, and referrals to, a mental health specialist must also be available.

Finally, at the patient level, education of older adults and their families to decrease stigma, increase help-seeking and efforts to foster engagement and adherence to treatment are necessary. Embedding mental health care in the PCC and following other guidelines of collaborative care models have shown to be effective in Western studies (Katon et al., 2010; Unutzer et al., 2002). The same scheme should be suitably adapted to the Chinese cultural context, and this will offer huge promises in the enhancement of public health in the aged sector.

8. Strengths and limitations

The two-stage design and the use of the SCID by trained clinician researchers for systematic diagnosis are strengths of the study. Its limitations include the sampling frame and the cross-sectional design. We sampled only one neighborhood clinic in one relatively affluent city in China. Therefore, our findings may not apply to rural areas or other urban areas. Results may also vary between clinics based on different characteristics of the neighborhoods they serve. It seems unlikely that late life depression management and outcomes would be better in PCCs in less well-resourced areas. Rather, they would likely be worse, complicated by social stressors associated with both depression and lower socioeconomic status.

Because of the cross-sectional design, we cannot conclude that the correlates of late-life depression observed here caused the illness, or that they may necessarily serve as risk factors guiding the development of future prevention strategies. Also, the choice of correlates we examined was driven in large part by results of studies in the Western literature. There may be other factors uniquely important to the pathogenesis of depression in Chinese elders that we did not measure.

In summary, late-life depression in China primary care is a common condition. Its prevalence is high among individuals with older age, female gender, poorer social support, and more physical illnesses. Under the current treatment conditions, the depressive symptoms in older PCC patients are likely to persist, continuing to expose older adults to emotional sufferings and associated risks for social and physical morbidity. China is faced with a great opportunity to improve mental health care for its older adults through more detailed studies of the barriers to depression management in older adults, and through the design and testing of appropriate interventions in urban primary care clinics. Lessons learned from studies of collaborative depression care management interventions may be particularly informative.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the valuable suggestions and contributions made by members of the Trial Monitoring Committee (TMC). The TMC is chaired by Professor Eric Caine and Professor Yeates Conwell from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center, USA. The other members are:

Professor Helen Chiu, Chair of the Department of Psychiatry, Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

Professor Shuiyuan Xiao, Head of the Public Health School, Central South University, China

Professor Xin Tu, Department of Biostatistics, University of Rochester Medical Center, USA

Professor Mowei Shen, Chair of Department of Psychology, Zhejiang University, China.

Role of funding source

The project described was supported by award number R01TW008699 from the Fogarty International Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Fogarty International Center or the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the grant “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” from the Ministry of Education, China.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All authors have read the paper and are in agreement with the contents.

References

- Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Braam AW, Smit JH, Van TW. Consequences of major and minor depression in later life: a study of disability, well-being and service utilization. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(6):1397–1409. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisschop MI, Kriegsman DM, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, van TW. The longitudinal relation between chronic diseases and depression in older persons in the community: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57(2):187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2003;58(3):249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Chiu H, Xu B, Ma Y, Jin T, Wu M, Conwell Y. Reliability and validity of the PHQ-9 for screening late-life depression in Chinese primary care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;25(11):1127–1133. doi: 10.1002/gps.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi I, Chou KL. Social support and depression among elderly Chinese people in Hong Kong. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2001;52(3):231–252. doi: 10.2190/V5K8-CNMG-G2UP-37QV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi I, Yip PS, Chiu HF, Chou KL, Chan KS, Kwan CW, Conwell Y, Caine E. Prevalence of depression and its correlates in Hong Kong’s Chinese older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(5):409–416. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Municipal Committee for Aging People. China’s elderly today and future8–24. 2011 http://www.cncaprc.gov.cn/info/15108.html.

- Chiu HC, Chen CM, Huang CJ, Mau LW. Depressive symptoms, chronic medical conditions and functional status: a comparison of urban and rural elders in Taiwan. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):635–644. doi: 10.1002/gps.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Lyness JM, Tang W, Tu X, Conwell Y. Outcomes and predictors of late-life depression trajectories in older primary care patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(5):406–415. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181693264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, Alonso J, Haro JM, Vilagut G, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Webb C, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Anthony JC, Von Korff MR, Wang PS, Brugha TS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM, Ustun TB, Chatterji S. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B, Conwell Y, Delavan RL. Correlates of late-life major depression: a comparison of urban and rural primary care patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(1):28–41. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000224732.74767.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Jin Y, Unverzagt FW, Liang C, Hall KS, Ma F, Murrell JR, Cheng Y, Matesan J, Li P, Bian J, Hendrie HC. Correlates of depressive symptoms in rural elderly Chinese. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1358–1366. doi: 10.1002/gps.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J, Rolnick SJ, Nitz NM, Luepke L, Jackson J, Fischer LR, Leibson C, Bland PC, Heinrich R, Waller LA. Clinical detection of depression among community-based elderly people with self-reported symptoms of depression. The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1998;53(2):M92–M101. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.2.m92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangzhou Government. Year Book of Hangzhou. 2009 http://www.hzstats.gov.cn/web/default.aspx.

- Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale. Original observer-rated version. “Does do” form—for women only. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1988;24(4):785–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von KM, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, Peterson D, Rutter CM, McGregor M, McCulloch D. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai DW. Depression among elderly Chinese-Canadian immigrants from Mainland China. Chinese Medical Journal. 2004;117(5):677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, Mulsant BH, Rollman BL, Dew MA, Schulz R, Reynolds CF., III The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9(2):113–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1968;16(5):622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, Yu Q, Tang W, Tu X, Conwell Y. Risks for depression onset in primary care elderly patients: potential targets for preventive interventions. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1375–1383. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Xiang YT, Li SR, Xiang YQ, Guo HL, Hou YZ, Cai ZJ, Li ZB, Li ZJ, Tao YF, Dang WM, Wu XM, Deng J, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of depression in an elderly population living with family members in Beijing, China. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(12):1723–1730. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Bouhuys AL, Brilman EI, Ormel J. Functional disability and neuroticism as predictors of late-life depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9(3):241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos FC, Petridou E, Argyropoulou S, Kontaxakis V, Dessypris N, Anastasiou A, Katsiardani KP, Trichopoulos D, Lyketsos C. Prevalence and correlates of depression in late life: a population based study from a rural Greek town. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):350–357. doi: 10.1002/gps.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park L, X Z, W J, P JM. Mental health care in China: recent changes and future challenges. Harvard Health Policy Review. 2005;6(3):35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Gladstone G, Chee KT. Depression in the planet’s largest ethnic group: the Chinese. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):857–864. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z, Ding Z, Pang S, Li X, Zhang Y, Wang Z. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2041–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health in China: as living standards rise, so does the demand for mental care8–16. The Economist. 2007 http://www.economist.com/node/9657086.

- Tong AY, Man DW. The validation of the Hong Kong Chinese version of the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale for institutionalized elderly persons. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2002;22:132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Travis LA, Lyness JM, Shields CG, King DA, Cox C. Social support, depression, and functional disability in older adult primary-care patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, la Penna RD, Noel PH, Lin EH, Arean PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Kushner K, Frey JJ, Du XP, Qian N. Primary care reform in the Peoples’ Republic of China: implications for training family physicians for the world’s largest country. Family Medicine. 2007a;39(9):639–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Kushner K, Frey JJ, III, Du XP, Qian N. Primary care reform in the Peoples’ Republic of China: implications for training family physicians for the world’s largest country. Family Medicine. 2007b;39(9):639–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JW, Jr, Rost K, Dietrich AJ, Ciotti MC, Zyzanski SJ, Cornell J. Primary care physicians’ approach to depressive disorders. Effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Archives of Family Medicine. 1999;8(1):58–67. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung A, Chan R, Mischoulon D, Sonawalla S, Wong E, Nierenberg AA, Fava M. Prevalence of major depressive disorder among Chinese-Americans in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WX, Shen YC, Li SR. Epidemiological investigation on mental disorders in 7 areas of China. Chinese Journal of Psychiatry (in Chinese) 1998;31:69–77. [Google Scholar]