Abstract

Aim

To explore socio-demographic factors, health risks and harms associated with early initiation of injecting (before age 16) among injecting drug users (IDUs) in Tallinn, Estonia.

Methods

IDUs were recruited using respondent driven sampling methods for two cross-sectional interviewer-administered surveys (in 2007 and 2009). Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with early initiation versus later initiation.

Results

A total of 672 current IDUs reported the age when they started to inject drugs; the mean was 18 years, and about a quarter of the sample (n=156) reported early initiation into injecting drugs. Factors significantly associated in multivariate analysis with early initiation were being female, having a lower educational level, being unemployed, shorter time between first drug use and injecting, high-risk injecting (sharing syringes and paraphernalia, injecting more than once a day), involvement in syringe exchange attendance and getting syringes from outreach workers, and two-fold higher risk of HIV seropositivity.

Conclusions

Our results document significant adverse health consequences (including higher risk behaviour and HIV seropositivity) associated with early initiation into drug injecting and emphasize the need for comprehensive prevention programs and early intervention efforts targeting youth at risk. Our findings suggest that interventions designed to delay the age of starting drug use, including injecting drug use, can contribute to reducing risk behaviour and HIV prevalence among IDUs.

Keywords: Adolescents, injecting drug use, risk behaviour, Eastern Europe, Respondent Driven Sampling, HIV

Introduction

Several countries in Eastern Europe have witnessed an explosive epidemic of injection drug use contributing to an HIV prevalence among adults (15–49 years) estimated to be over 1% (1.0% in Russia, 1.1% in Ukraine, and 1.2% in Estonia in 2009) (UNAIDS, 2010). In the 1990s, several newly independent states faced major socio-political and economic changes, which contributed to poor health outcomes, reductions in life expectancy, and the spread of injecting drug use among vulnerable social groups (Mathers et al., 2010; Rhodes et al., 1999; Uusküla et al., 2002). There are approximately 14,000 IDUs in Estonia giving a prevalence of 2.4% of the adult population (aged 15–44) (Uusküla et al., 2007). Recent assessment of Central and Eastern Europe countries (including Estonia) revealed that initiation into drug use, including injecting, usually starts in the late teens, but may occur as young as 12 to 14 years of age (EHRN, 2009; Merkinaite, Grund, & Frimpong, 2010).

Prior research has shown that earlier onset of illicit drug taking is associated with an increased risk of problematic drug use or dependence problems (Anthony, & Petronis, 1995; Friedman et al., 1989; Fuller et al., 2001; Neaigus et al., 1996). Factors associated with early adolescent initiation into injecting (≤16 years) are being female, involved in sex work, binge drinking and early criminal behaviour (Miller, Strathdee, Kerr, Li, & Wood, 2006). Early adoption of other behaviours such as smoking, use of alcohol, marijuana or heroin and belonging to a high-risk network of injecting drug users are also risk factors for early initiation into injecting (Cheng et al., 2006; Fuller et al., 2003; Sherman et al., 2005). It is known that younger IDUs are at high risk of acquiring HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) and engage in risky injection practices such as more frequent injecting, sharing syringes, and in sex-related risk behaviours such as early sexual initiation, having unprotected sex, having a higher number of sexual partners, and early involvement in commercial sex (Becker Buxton et al., 2004; Des Jarlais et al., 1999; Fuller et al., 2001; Fuller et al., 2002; Kral, Lorvick, & Edlin, 2000; Miller, Strathdee, Li, Kerr, & Wood, 2007a). Due to their high risk behaviours young IDUs have a higher risk of premature mortality than the general population (Miller, Kerr, Strathdee, Li, & Wood, 2007b).

Adolescent risk-taking has been described as a significant public health concern and understanding whether early initiation of drug injection might affect later drug problems could help to target prevention and early interventions. The aim of our study was to determine socio-demographic factors, health risks and harms associated with early initiation of injecting (before age 16) among current IDUs in Tallinn, Estonia.

Methods

Cross-sectional studies using respondent-driven sampling (RDS) subject recruitment methods were used to recruit IDUs for interviewer-administered surveys in 2007 and 2009 in Tallinn, Estonia (Uusküla et al., 2011). The RDS is a chain referral based effective technique often used to sample IDUs including accessing individuals who may not appear in public venues and are not in contact with service providers (Heckathorn, 2002; Malekinejad et al., 2008; Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). Inclusion criteria for the studies were being 18 years or older, Russian or Estonian language speakers, having injected in the previous two months and being able to provide informed consent. Recruitment began with the non-random selection of five to six ‘seeds’ representing diverse IDU types (by gender, ethnicity, main type of drug used, engaging in sex for money, and HIV status). Eligible participants were provided with coupons for recruiting up to three of their peers. Coupons were uniquely coded to link participants to their survey responses and biological specimens and for monitoring who recruited whom. Participants who completed the study received a primary incentive (a food voucher worth 6.4 EUR) for participation in the study and a secondary incentive (food vouchers worth 3.2 EUR for each eligible person they recruited to the study). A total of 350 IDUs were recruited in 2007 and 331 IDUs in 2009 in Tallinn. The main characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bivariate associations of characteristics and behaviours at initiation of drug injection: comparing early initiators to later initiators from surveys of IDUs in Tallinn, Estonia in 2007 and 2009

| Overall | ≤15 years | >15 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p-value | |

| Characteristics at injecting initiation | |||||||

| Age at IDU initiation (mean, SD) | 672 | (18.5; 4.4) | 156 | (14.0; 1.2) | 516 | (19.8; 4.1) | - |

| Gender: | |||||||

| Male | 559 | 83 | 120 | 77 | 438 | 85 | |

| Female | 114 | 17 | 36 | 23 | 78 | 15 | 0.020 |

| Ethnicity: | |||||||

| Russian/Russian speaking | 560 | 89 | 139 | 91 | 420 | 88 | |

| Estonian | 71 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 58 | 12 | 0.224 |

| Drug use initiation: | |||||||

| By other means of administration | 429 | 64 | 90 | 58 | 338 | 66 | |

| Injecting | 244 | 36 | 66 | 42 | 178 | 34 | 0.075 |

| Years from first illicit drug use to first injecting (mean in years; SD) | 555 | (1.3; 2.0) | 132 | (0.5; 0.8) | 423 | (1.6; 2.2) | <0.001 |

| Injected first time with used needle/syringe | |||||||

| No | 573 | 89 | 126 | 85 | 446 | 90 | |

| Yes | 73 | 11 | 23 | 15 | 50 | 10 | 0.070 |

| Current characteristics | |||||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 673 | (27.1; 5.6) | 156 | (23.8; 3.7) | 516 | (28.1; 5.7) | <0.001 |

| Educational level (years): | |||||||

| 10–12 | 327 | 49 | 43 | 28 | 284 | 55 | |

| <9 | 345 | 51 | 113 | 72 | 231 | 45 | <0.001 |

| Main source of income in last 6 months: | |||||||

| Regular or temporary job | 298 | 44 | 47 | 30 | 250 | 48 | |

| Other | 375 | 56 | 109 | 70 | 266 | 52 | <0.001 |

| Duration of injecting (mean in years; SD) | 672 | (8.6; 4.7) | 156 | (9.8; 3.8) | 516 | (8.3; 4.8) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of injecting: | |||||||

| Less than daily | 339 | 51 | 74 | 48 | 264 | 52 | |

| Daily | 327 | 49 | 81 | 52 | 246 | 48 | 0.380 |

| Likelihood of injecting per day: | |||||||

| Once | 168 | 25 | 27 | 17 | 141 | 27 | |

| More than once | 503 | 75 | 129 | 83 | 373 | 73 | 0.011 |

| Main drug injected during last 4 weeks: | |||||||

| Fentanyl | 411 | 61 | 105 | 67 | 305 | 60 | 0.066 |

| Amphetamine | 174 | 26 | 33 | 22 | 141 | 27 | 0.123 |

| Ever had non-fatal overdose: | |||||||

| No | 232 | 34 | 45 | 29 | 186 | 36 | |

| Yes | 441 | 66 | 111 | 71 | 330 | 64 | 0.097 |

| Sharing syringes during last 4 weeks: | |||||||

| No | 510 | 76 | 107 | 69 | 402 | 78 | |

| Yes | 159 | 24 | 48 | 31 | 111 | 22 | 0.017 |

| Sharing paraphernalia during last 4 weeks: | |||||||

| No | 455 | 68 | 93 | 60 | 362 | 71 | |

| Yes | 213 | 32 | 62 | 40 | 150 | 29 | 0.012 |

| Main source for syringes during last 4 weeks: | |||||||

| Pharmacy | 179 | 31 | 26 | 19 | 153 | 34 | |

| Syringe exchange points | 320 | 54 | 81 | 60 | 238 | 53 | |

| Outreach worker | 90 | 15 | 29 | 21 | 61 | 14 | 0.002 |

| Number of sexual partners (last 12 months): | |||||||

| None or one | 388 | 58 | 90 | 58 | 298 | 58 | |

| More than one | 282 | 42 | 65 | 42 | 216 | 42 | 0.985 |

| Condom use (last 4 weeks): | |||||||

| Always | 167 | 40 | 44 | 28 | 123 | 24 | |

| Never/Occasionally | 253 | 60 | 61 | 39 | 192 | 37 | 0.604 |

| Self-reported STI (syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, genital herpes): | |||||||

| No | 602 | 90 | 145 | 93 | 456 | 89 | |

| Yes | 69 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 58 | 11 | 0.128 |

| Ever tested for HIV | |||||||

| No | 95 | 14 | 21 | 13 | 74 | 14 | |

| Yes | 576 | 86 | 135 | 87 | 440 | 86 | 0.769 |

| Disease serostatus: | |||||||

| HIV+ | 354 | 53 | 105 | 68 | 249 | 48 | <0.001 |

Face-to-face interviews using an interviewer-administered questionnaire were used in both studies, based on the WHO Drug Injecting Study Phase II survey (version 2b (rev.2)) (Des Jarlais, Perlis, Stimson, Poznyak, & WHO Phase II Drug Injection Collaborative Study Group, 2006). We elicited information on demographics, drug use history, HIV risk behaviour, HIV testing, and access to and use of harm reduction services. Interviews were conducted, in confidence, in a room of the syringe exchange programme (SEP). Recruitment was conducted and the surveys handled by a team of trained fieldworkers. The study protocols included pre- and post-HIV test counseling for study participants.

Venous blood was collected from participants and tested with Vironostika HIV Uniform II Ag/Ab (BioMerieux) test kits in 2007 and using Abbott IMx HIV-1/HIV-2 III Plus test kits (Abbott Laboratories) in 2009. Such HIV test kits have proved to have high sensitivity and specificity (>99%) (Thorstensson et al., 1998; Weber, 1998). The testing was done by the national HIV reference laboratory in Tallinn.

The 2007 and 2009 samples were initially analysed separately to check for any differences between the samples. However, factors used in the analysis did not differ between the study years and therefore data from 2007 and 2009 were combined to increase statistical power for the analysis. To control for potential duplication in the samples (recruited in 2007 and 2009) selected personal characteristics (sex, ethnicity, date of birth) were used. Using this method, eight individuals were identified who possibly participated in both surveys. These persons were therefore removed from the 2009 sample. IDUs were categorized into two groups: “early initiators” reported starting injecting drugs at 15 years or younger while “later initiators” reported starting injecting at 16 years or older. As the data were combined from two separate RDS surveys, it was not feasible to do RDSAT weighting for the combined dataset. We therefore used the combined data as a single convenience sample, recruited in two time periods but without duplication.

Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for continuous variables. For categorical variables, percentages (%) and absolute (n) frequencies are presented. 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated to give an estimate of population parameters. For trend analysis of proportions a chi-squared statistic was calculated. Chi-squared test, Fisher exact test and t-test were used to test statistical significance. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated using length of injecting career and study year as control variables in a multivariate logistic regression model. An additional analysis was done to assess the association between HIV serostatus and early injecting initiation. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used, with HIV status as the outcome measure and controlling for duration of injecting plus the effect of variables representing characteristics and events associated with beginning to inject that would probably have occurred before HIV infection.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Board of the Tallinn Medical Research Committee (in 2007) and from the University of Tartu, Estonia (in 2009).

Results

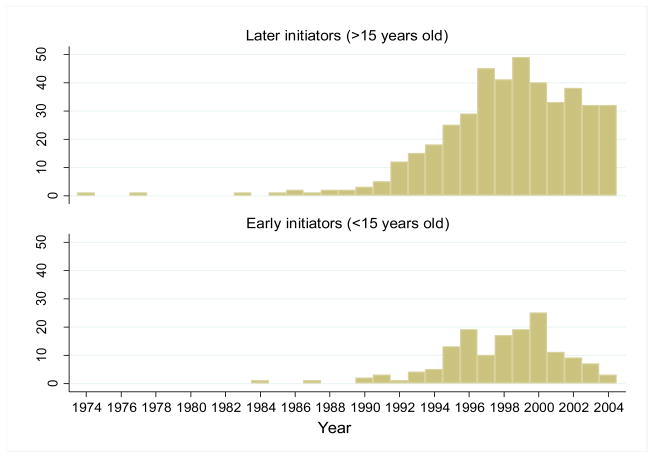

The mean age of starting to inject drugs in the 672 current IDUs included in the analysis was 18 years with a range of 9 to 42 years. Almost a quarter (23%; n=156) reported early initiation (i.e at or below 15 years of age). The numbers of early and later initiators by calendar year are presented in the Figure. There is the rise in the mid and late 1990s and highest numbers of IDU initiators in the years 1996 to 2000. Since the 2000s, difference can be observed in the epidemic curves, the number of early initiators declined while the numbers of later initiators remained relatively unchanged, p<0.001.

Figure*.

Number of later and early injecting initiators beginning injecting by calendar years.

* The figure presents the timeline until 2004 because the study only recruited IDUs over the age of 18. Participants who had initiated injecting at 15 or younger would not have been eligible to participate in the 2007 study.

At the time of the study, early initiators were younger, more likely to be female, had a lower educational level and were more likely to report other than part or fulltime work as their main source of income compared with the later initiators (Table 1).

Early initiators had a three times shorter interval between from initiation of illicit drug use to escalating into injecting drugs. Concerning injecting practices they tended to have a longer duration of injecting, reported a higher likelihood of daily injecting, and more likely to report sharing either syringes or injection paraphernalia (Table 1). They were more likely to share syringes with sexual partners (47% vs 31%, p=0.029) and/or to get used syringes from dealers (16% vs 2%, p<0.001), (information has not been provided in the tables), though a higher proportion of early initiators relied on SEPs and outreach as a main source for new syringes than later initiators (Table 1).

There were no statistically significant differences in sexual behaviours including number of sexual partners, condom use or self-reported sexually transmitted infections (STI). Early initiators were more likely to be HIV infected compared with later initiators (Table 1). The majority of participants (86%) had previously been tested for HIV, but of the HIV infected cases, 37% (n=33) of early initiators and 43% (n=93) of later initiators were unaware of their HIV positive status (i.e. considered themselves negative at the time of the interview); this difference was not statistically significant.

After adjusting for duration of injecting career and study year, several socio-demographic and risk behaviour factors were associated with early initiation of injecting. The socio-demographic characteristics associated with early injecting initiation were being female, having a lower educational level and being without employment (Table 2). The health-risks and harms related to early initiation of injecting were: shorter time period from first illicit drug use to first injecting, higher likelihood of current injecting per day, higher odds of sharing syringes and paraphernalia, (Table 2). Early initiators had higher likelihood of using SEPs or outreach as a source for clean syringes

Table 2.

Factors associated with early initiators versus later initiators among surveys of IDUs in Tallinn, Estonia in 2007 and 2009, multivariate analysis

| OR | 95%CI | AOR* | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.7 | 1.1–2.6 | 1.7 | 1.1–2.7 |

| Educational level (years): | ||||

| 10–12 | 1 | |||

| <9 | 3.2 | 2.2–4.8 | 3.9 | 2.6–5.9 |

| Main source of income in last 6 months: | ||||

| Regular or temporary job | 1 | |||

| Other | 2.2 | 1.5–3.2 | 2.0 | 1.4–3.0 |

| Years from first illicit drug use to first injecting | 0.6 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4–0.7 |

| Intensity of injecting per day: | ||||

| One | 1 | |||

| More than one | 1.8 | 0.1–2.9 | 1.9 | 1.2–3.0 |

| Sharing syringes during last 4 weeks: | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.1–2.4 | 1.6 | 1.1–2.4 |

| Sharing paraphernalia during last 4 weeks: | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.1–2.3 | 1.7 | 1.1–2.4 |

| Main source for syringes during last 4 weeks: | ||||

| Pharmacy | 1 | 1 | ||

| Syringe exchange points | 2.0 | 1.2–3.3 | 1.9 | 1.2–3.2 |

| Outreach worker | 2.8 | 1.5–5.1 | 2.5 | 1.3–4.6 |

| Disease serostatus: | ||||

| HIV+ | 2.2 | 1.5–3.3 | 2.1 | 1.4–3.1 |

adjusted for length of injecting career and year of study

The almost two-fold higher risk of being HIV positive may be the most important consequence of beginning to inject at a very young age. We did an additional analysis to evaluate the association between HIV serostatus and early injecting adjusting for gender, ethnicity, illicit drug use initiation by injecting or not, years from first illicit drug use to first injection, study year and duration of injecting. After controlling for these additional factors, the risk of being HIV infected for early initiators remained almost the same as before (AOR: 1.8; 95% CI 1.2–2.9).

Discussion

This is the first study looking at the correlates and consequences of adolescent injection drug use initiation from the Eastern European region where high prevalence HIV epidemics together with IDU epidemics among young people have been documented (UNAIDS, 2010). Our results are in agreement with other studies from the region documenting the evolution of the IDU epidemics from the mid 1990s to early 2000s – the period after the collapse of the Soviet Union (Rhodes et al., 1999).

Initiation into injection drug use can occur at a very early age. About a quarter of the IDUs in our sample started injecting at age 15 or younger and the youngest was only nine years old. Our findings show an increase in the number of early injectors from the 1990s until 2000 - the period of major socio-economic changes due to the break-up of the Soviet Union. The decline in early drug use after 2000 could be related to improvements in the socio-economic situation in Estonia, also greater awareness and concern about AIDS and the harmful effects of injection drug use (Uusküla et al., 2011). Mortality may also have affected the observed trend, given that injection drug use was extremely rare before the 1990s and the HIV epidemic among IDUs emerged in the early 2000s so mortality in this cohort may have been high (Uusküla et al., 2002). However, it would seem very unlikely that differential mortality would have created the trend in the decline in very young injectors during the 2000s.

Our findings suggest that those who start injecting drugs early differ significantly from their older initiate counterparts. These findings have some important implications for the development of interventions. First, there are implications for health educators who are developing and implementing prevention programmes. As reported previously, and confirmed by our results, girls may be at higher risk of starting to inject early, therefore specific interventions aimed at girls should be considered (Frajzyngier, Neaigus, Gyarmathy, Miller, & Friedman, 2007; Miller, Strathdee, Kerr, Li, & Wood, 2006). In addition, our finding that about a quarter of current IDUs started injecting drugs when aged 15 or younger suggest the need for comprehensive, evidence-based and non-judgmental programmes for adolescents initiated during elementary school and continued at least through middle school (DuRant, Smith, Kreiter, & Krowchuk, 1999; Kokkevi, Nic Gabhainn, Spyropoulou, & Risk Behaviour Focus Group of the HBSC, 2006). Prevention programmes should focus on the environment surrounding young people – their family, school and community – and on the social and behavioural aspects, rather than drug use itself (Babor et al., 2010; Merkinaite, Grund, & Frimpong, 2010).

Secondly, there are implications for public health professionals and for primary health care providers. Lower educational level among early initiators suggests that they may have dropped out of school due to their drug use and it is important that institutions working with adolescents, besides schools, are alert to the early signs of problem behaviour that may indicate drug use and are equipped to refer such adolescents to specialists and to appropriate interventions (DuRant, Smith, Kreiter, & Krowchuk, 1999; McLellan & Meyers, 2004; Winters, 1999). Also there should not be any age restrictions on access to harm reduction services such as syringe exchange and substitution therapy (EHRN, 2009). For example if a very young IDU comes to a syringe exchange there should be clear policy about where to refer this young person and how to help them.

We found higher injecting risk behaviour with higher HIV prevalence among those who initiated drug injection at an early age versus those who started later. Along with prevention programmes there is a need to increase the coverage of harm reduction interventions among IDUs, e.g. specialized drug treatment programs for adolescents and their families might be particularly helpful.

Given the design of our study we cannot determine the extent to which early drug injection is itself a cause of higher HIV risk behaviour, educational and employment problems versus early drug injection simply being a marker for other psychological and social problems that are more fundamental causes of risk behaviour. Nevertheless, independent effects of age of initiation on later development of problematic drug use or dependence problems, irrespective of other factors, have been suggested previously (Anthony & Petronis, 1995; Kokkevi, Nic Gabhainn, Spyropoulou, & Risk Behaviour Focus Group of the HBSC, 2006; Sung, Erkanli, Angold, & Costello, 2004). The limitations of our study include the fact that the data is based entirely on self-reports and may thus be subject to recall bias and, given the sensitive nature of the behaviours, may be biased by socially desired responses. However, we would not expect these biases to operate differently for early and later initiates, therefore any such biases should not affect comparisons between these groups. Our sampling method may have affected the representativeness of the study. However RDS was used for recruitment because it has proved to be an efficient sampling technique for hard-to-reach groups (Heckathorn, 2002; Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). The source studies were not designed to evaluate the period of drug use and injection drug use initiation, therefore we could not collect some important information on aspects such as the risks among early and later initiators of fatal overdoses, comorbidites or premature death.

In conclusion our findings suggest multiple adverse health consequences – HIV infection in particular – associated with early initiation into drug injecting in Estonia. Our findings emphasize the need for comprehensive prevention programs, early intervention efforts targeting young people at risk of early initiation into drug injecting and policies aimed at delaying the age of starting drug use, including injecting drug use, which may contribute to reducing risk behaviour among IDUs.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Civilian Research Development Foundation grant ESBI-7002-TR-08 and by NIH grant R01 AI0832035, and by Target Financing of Estonian Ministry of Education and Research grant SF0180060s09. Also by European Commission funded project: Expanding Network for Comprehensive and Coordinated Action on HIV/AIDS prevention among IDUs and Bridging Population (ENCAP) No 2005305, Global Fund to Fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria Program called “Scaling up the response to HIV in Estonia” for 2003–2007 (grant EST-202-G01-H-00) and National HIV/AIDS Strategy for 2006–2015.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Caulkins J, Edwards G, Fischer B, Foxcroft D, Humphreys K, et al. Drug Policy and the Public Good. Oxford: Oxford UP; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Buxton M, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA, Des Jarlais DC, Morse EV, Ouellet L, et al. Association between injection practices and duration of injection among recently initiated injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Sherman SG, Srirat N, Vongchak T, Kawichai S, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. Risk factors associated with injection initiation among drug users in Northern Thailand. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Perlis T, Chapman TF, Sotheran JL, Paone D, et al. Risk behavior and HIV infection among new drug injectors in the era of AIDS in New York City. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 1999;20:67–72. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199901010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Perlis TE, Stimson GV, Poznyak V WHO Phase II Drug Injection Collaborative Study Group. Using standardized methods for research on HIV and injecting drug use in developing/transitional countries: case study from the WHO Drug Injection Study Phase II. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:286–291. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurasian Harm Reduction Network (EHRN) Young people and injecting drug use in selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Vilnius: EHRN; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frajzyngier V, Neaigus A, Gyarmathy VA, Miller M, Friedman SR. Gender differences in injection risk behaviors at the first injection episode. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, Neaigus A, Abdul-Quader A, Sotheran JL, Sufian M, et al. AIDS and the new drug injector. Nature. 1989;339:333–334. doi: 10.1038/339333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(Suppl 1):136–145. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Ompad DC, Shah N, Arria A, Strathdee SA. High-risk behaviors associated with transition from illicit non-injection to injection drug use among adolescent and young adult drug users: a case-control study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Latkin CA, Ompad DC, Celentano DD, Strathdee SA. Social circumstances of initiation of injection drug use and early shooting gallery attendance: implications for HIV intervention among adolescent and young adult injection drug users. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;32:86–93. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200301010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems. 2002;49:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Fact sheet 2010. 2010 Retrieved 29th February 2012 from http://www.unaids.org/documents/20101123_FS_eeca_em_en.pdf. [PubMed]

- Kokkevi A, Nic Gabhainn S, Spyropoulou M Risk Behaviour Focus Group of the HBSC. Early initiation of cannabis use: a cross-national European perspective. Journal of Adolescence Health. 2006;39:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Lorvick J, Edlin BR. Sex- and drug-related risk among populations of younger and older injection drug users in adjacent neighbourhoods in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2000;24:162–167. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malekinejad M, Johnston LG, Kendall C, Kerr LR, Rifkin MR, Rutherford GW. Using respondent-driven sampling methodology for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in international settings: a systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12 (4 Suppl):S105–130. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375:1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkinaite S, Grund JP, Frimpong A. Young people and drugs: next generation of harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2010;21:112–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Strathdee SA, Kerr T, Li K, Wood E. Factors associated with early adolescent initiation into injection drug use: implications for intervention programs. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:462–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Strathdee SA, Li K, Kerr T, Wood E. A longitudinal investigation into excess risk for blood-borne infection among young injection drug users (IDUs) American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007a;33:527–536. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Li K, Wood E. Factors associated with premature mortality among young injection drug users in Vancouver. Harm Reduction Journal. 2007b;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment: A review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neaigus A, Friedman SR, Jose B, Goldstein MF, Curtis R, Ildefonso G, et al. High-risk personal networks and syringe sharing as risk factors for HIV infection among new drug injectors. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 1996;11:499–509. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Ball A, Stimson GV, Kobyshcha Y, Fitch C, Pokrovsky V, et al. HIV infection associated with drug injecting in the newly independent states, eastern Europe: the social and economic context of epidemics. Addiction. 1999;94:1323–1336. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2004;34:193–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Fuller CM, Shah N, Ompad DV, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Correlates of initiation of injection drug use among young drug users in Baltimore, Maryland: the need for early intervention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:437–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10399817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung M, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello EJ. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity on the development of substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorstensson R, Andersson S, Lindbäck S, Dias F, Mhalu F, Gaines H, et al. Evaluation of 14 commercial HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody assays using serum panels of different geographical origin and clinical stage including a unique seroconversion panel. Journal of Virological Methods. 1998;70:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusküla A, Kalikova A, Zilmer K, Tammai L, DeHovitz J. The role of injection drug use in the emergence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection in Estonia. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;6:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(02)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusküla A, Rajaleid K, Talu A, Abel K, Rüütel K, Hay G. Estimating injection drug use prevalence using state wide administrative data sources: Estonia, 2004. Addiction Research & Theory. 2007;15:411–424. [Google Scholar]

- Uusküla A, Des Jarlais DC, Kals M, Rüütel K, Abel-Ollo K, Talu A, et al. Expanded syringe exchange programs and reduced HIV infection among new injection drug users in Tallinn, Estonia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:517. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Treating adolescents with substance use disorders: an overview of practice issues and treatment outcome. Substance Abuse. 1999;20:203–225. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber B. Multicenter evaluation of the new automated Enzymun-Test Anti-HIV 1 + 2 + subtyp O. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1998;36:580–584. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.580-584.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]