Abstract

Sphingomyelins (SMs) and ceramides are known to interact favorably in bilayer membranes. Because ceramide lacks a headgroup that could shield its hydrophobic body from unfavorable interactions with water, accommodation of ceramide under the larger phosphocholine headgroup of SM could contribute to their favorable interactions. To elucidate the role of SM headgroup for SM/ceramide interactions, we explored the effects of reducing the size of the phosphocholine headgroup (removing one, two, or three methyls on the choline moiety, or the choline moiety itself). Using differential scanning calorimetry and fluorescence spectroscopy, we found that the size of the SM headgroup had no marked effect on the thermal stability of ordered domains formed by SM analog/palmitoyl ceramide (PCer) interactions. In more complex bilayers composed of a fluid glycerophospholipid, SM analog, and PCer, the thermal stability and molecular order of the laterally segregated gel domains were roughly identical despite variation in SM headgroup size. We suggest that that the association between PCer and SM analogs was stabilized by ceramide’s aversion for disordered phospholipids, by interfacial hydrogen bonding between PCer and the SM analogs, and by attractive van der Waals’ forces between saturated chains of PCer and SM analogs.

Introduction

Sphingomyelins (SMs) are important constituents of cellular membranes, markedly enriched in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (1–3). Together with cholesterol, they are thought to form specialized membrane domains (lipid rafts) (4). The exact definition of lipid rafts is still a matter of discussion (5) but in general they are suggested to be involved in compartmentalization of cellular processes such as sphingolipid and protein transport (2). As a response to various extracellular ligands such as cytokines and growth factors, the SMs in cellular membranes, or in membrane lipid rafts, can be converted to ceramides by the action of sphingomyelinases that catalyze the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond in SM releasing free phosphocholine and ceramide (6–8). Ceramides generated by sphingomyelinase activation may act as second messengers in cell signaling events (9–12), and are capable of modulating membrane structure and dynamics as they induce formation of ceramide-enriched gel (13) or liquid-condensed domains (14–16). Ceramides and SMs have been observed to interact favorably in bilayer membranes (17,18), which results in the formation of lateral sphingolipid-rich gel phase domains (19,20). Ceramides, as well as cholesterol, are able to reduce steric repulsion between the bulky headgroups of SM (13), maximizing chain-chain interactions and bringing the lipids closer together. SM-ceramide interactions are further enhanced by the extensive net of hydrogen bonds formed at the membrane-water interface owing to the C3-hydroxyl and the C2-amide functions of the sphingoid base that forms the backbone of sphingolipids (21–23).

The importance of a phospholipid headgroup in shielding the hydrophobic portion of other membrane lipids with smaller polar headgroups from unfavorable interactions with the aqueous environment was initially proposed for phospholipid/cholesterol mixtures in the umbrella model (24,25). According to this model, the large headgroup of the membrane phospholipids is suggested to act as an umbrella for the intercalated cholesterol molecule, shielding its nonpolar part from water molecules at the membrane interface. In agreement with the proposed model, we observed that the size of the SM headgroup is crucial for SM-sterol interactions in bilayers (26). A systematic reduction in palmitoyl-SM (PSM) headgroup size was observed to cause a decrease in the molecular area of PSM with a simultaneous increase in acyl-chain order (26). These changes in molecular properties significantly affected the formation of SM/sterol-rich ordered domains and decreased the affinity of sterol for bilayer membranes. Similarly to cholesterol, the small hydroxyl headgroup of ceramide is insufficient to shield the hydrophobic body of ceramide from unfavorable interactions with water. Thus, as seen with cholesterol, the SM headgroup can be expected to be of importance for SM-ceramide interactions in membranes as well. Together with the favorable interactions between the (often) saturated chains, as well as the extensive network of interlipid hydrogen bonding at the membrane-water interface, accommodation of ceramide under the large headgroup of SM could partly stabilize SM-ceramide interactions.

In this article, we explored the effect of systematically reducing the PSM headgroup size on SM-ceramide interactions. The interactions of palmitoyl ceramide (PCer) with SM analogs having none (ceramide phosphoethanolamine, CPE), one (CPEMe) or two (CPEMe2) methyl groups in the headgroup (for the structures of the analogs, see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material) were studied in binary mixtures, and in more complex bilayers that also contained a fluid glycerophospholipid. We even removed the choline moiety from SM to generate ceramide-1-phosphate. Using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and fluorescence spectroscopy we found that, in contrast to the effects reported earlier for SM-cholesterol interactions, reduction in the SM headgroup size had almost no effect on the interactions between SM and PCer in the bilayers. The SM analogs appeared equally able to form SM/ceramide-rich lateral domains, with similar thermostability and degree of molecular order. To shed light on the role of the chain-chain interactions and hydrogen bonding in the interlipid interactions of ceramides with phospholipids, we also investigated the effect of reduced headgroup size on the thermal stability of ceramide interactions with the corresponding glycerol-based headgroup analogs (i.e., DPPC, 1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphoethanolamine-dimethyl (DPPEMe2), DPPEMe, and DPPE; for the structures of the analogs, see Fig. S1) that have saturated acyl chains but reduced ability to hydrogen bonding compared to the SM analogs.

Moreover, the role of the saturated chains and hydrogen bonding was also studied by investigating the thermal stability of the SM analog interactions with dipalmitoyl glycerol (DPG). Similarly to ceramide, DPG has a small headgroup and saturated chains but due to the differences in the interface structure has reduced ability to hydrogen bonding compared to PCer. The results are discussed in terms of other features than the SM headgroup in stabilizing the SM-ceramide interactions, enabling the formation of SM/ceramide-rich phases regardless of the reduction in the size of the phosphocholine head of SM.

Material and Methods

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), DPPC, DPPE, DPPEMe, DPPEMe2, and 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl-(7-doxyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (7SLPC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). PCer was from Larodan Fine Chemicals (Malmö, Sweden). Cholesterol (Chol) and DPG were from Sigma/Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). PSM was purified from egg yolk sphingomyelin (Avanti Polar Lipids) as previously described in Maula et al. (27). It was 99% pure according to electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy analysis, and by analytical HPLC criteria. The SM headgroup analogs were synthesized as described before in Björkbom et al. (26). For simplicity, we will refer to the four sphingosine-based phospholipids as SM-analogs and the four glycerol-based phospholipids as PC-analogs.

Ceramide-1-phosphate (C-1-P, for structure, see Fig. S1) was synthesized from sphingosine-1-phosphate (Avanti Polar Lipids) by acylation of the NH2 with palmitic anhydride (2× molar excess) Sigma/Aldrich) in the presence of triethylamine (Sigma/Aldrich) (28). The reaction time was 10 min at 40°C. The product was isolated by preparative HPLC (29), using methanol with 1% NH4OH. Electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy analysis (methanol) indicated a molecular ion at 616.6 (M−). Analysis of C-1-P with Si60 thin-layer chromatography (chloroform/methanol/water 25:10:1.1 by vol) and spraying the plate with ninhydrin (0.2 mg/100 mL ethanol) then warming (150°C) indicated the total absence of a free NH2 group (compared to equal molar amount of sphingosine-1-phosphate). This suggested that the 3OH was not acylated (longer reaction times did, however, apparently lead to acylation of the 3OH; see also Nussbaumer et al. (30)). The lipids were dissolved as follows: POPC, PCer, Chol, PSM, and DPG in hexane/isopropanol (3:2 by vol), all PC-analogs in chloroform/methanol/H2O (60:40:1 by vol) CPEMe2 in methanol, and CPEMe, CPE, and C-1-P in methanol/H2O (100:1 by vol). Stock solutions of these lipids were stored at –20°C and warmed to ambient temperature before use.

N-trans-parinaroyl ceramide (tPA-Cer) was synthesized from trans-parinaric acid and D-sphingosine (Sigma/Aldrich) using the method described previously in Cohen et al. (31). tPA was prepared from α-linolenic acid as described before in Kuklev and Smith (32). After synthesis, tPA-Cer was identified by mass spectrometry and stored dry under argon at –87°C, until it was dissolved in argon-purged methanol and used within a week.

The water used for sample preparation was purified by reverse osmosis followed by passage through a UF-Plus water-purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA) to yield a product with final resistivity of 18.2 MΩcm. All other organic and inorganic chemicals were of the highest purity available, and solvents were of spectroscopic grade.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Multilamellar vesicles for differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were prepared by mixing the desired lipids (SM analog/PCer, 1:1 by mol, and POPC/SM analog/PCer, 70:15:15) and evaporating the solvent under a stream of nitrogen. The samples were then kept under vacuum for 1 h to remove any residual solvent. The resulting lipid films were hydrated with argon-purged Milli-Q (MQ, Millipore) water at 95°C for 30 min, followed by either sonication at 95°C (model No. 2510 bath sonicator; Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) for the ternary mixtures or five freeze-thaw cycles (between liquid nitrogen and water at 95°C) for the binary mixtures. This was interspersed with several rounds of intermittent vigorous vortex mixing until opalescent and macroscopically homogeneous preparations were obtained. Thin-layer chromatography of the preparation after sonication at 95°C did not reveal significant oxidation of the lipids.

Although sonication was sufficient for obtaining macroscopically homogeneous samples in ternary mixtures, different procedures had to be used because the binary mixtures required freeze-thaw cycles to become apparently homogenous. Samples were cooled down to room temperature and degassed for 5 min with a ThermoVac instrument (Microcal, Northampton, MA) before being loaded into the DSC. A quantity of 12–20 consecutive heating and cooling cycles were recorded for binary and ternary mixtures, respectively, at a temperature gradient of 1°C/min using a high-sensitivity VP-DSC instrument (Microcal). Data analysis was performed using the software ORIGIN (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). The binary mixtures were prepared to a final concentration of 1 mM and scanned between 20°C and 120°C, whereas the ternary mixtures were prepared to a concentration of 2 mM and scanned between 1°C and 80°C. Thermograms shown in the figures were selected from the last heating and cooling scans.

Fluorescence quenching

In our quenching assay, we use a fluorescent lipid that mimics the behavior of ceramide as well as possible (tPA-Cer). Its fluorescence will be quenched by 7SLPC. Because tPA-Cer will partition into gel phases, and 7SLPC into the disordered POPC phase, fluorescence from tPA-Cer will not be markedly quenched as long as the gel phase is intact, and the two molecules are physically separated. Heating will of course melt the gel phase, and consequently, tPA-Cer quenching will become more extensive. This is the principle we rely on in our assay.

Lipid vesicles for fluorescence-quenching experiments were prepared to a final lipid concentration of 50 μM with the indicated proportions of lipids. The lipids, tPA-Cer (1 mol %) and the quencher (7SLPC), were mixed and dried under a stream of nitrogen. Traces of solvent were removed in vacuum for at least 30 min. The dry lipid films were stored under argon at –20°C until hydrated one at a time for 30 min with preheated, argon-purged MQ-water at 65°C. Multilamellar vesicles were then formed by bath-sonication at 65°C for 5 min. Quenching data were collected with a QuantaMaster-1-spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, Lawrenceville, NJ) by measuring the fluorescence signal of tPA-Cer (excitation at 305 nm, emission at 405 nm) while heating the samples from 10°C to 65°C at a rate of 5°C/min.

The excitation and the emission slits were set to 3 nm, and the temperature was controlled by a Peltier element with a temperature probe immersed in the sample solution. The measurements were made in quartz cuvettes with a light path-length of 1 cm and the sample solutions were kept at a constant stirring (350 rpm/min) throughout the measurement. Fluorescence emission intensity was measured in the F-sample (quenched), where 30 mol % of 7SLPC replaced an equal amount of POPC, and the F0-sample (unquenched), containing no 7SLPC. Although the 7SLPC may not behave exactly as POPC (its partition into ordered phases is most likely slightly different from that of POPC), the bulky doxyl group is likely to disorder the acyl-chain region in a similar manner as the cis double bond of POPC. Fluorescence quenching was calculated using the PTI FeliX32-software (Photon Technology International) and reported as the F/F0 ratio against temperature.

Fluorescence lifetimes

Fluorescence lifetimes of tPA-Cer (1 mol %) and tPA (0.5 mol %) were initially measured in multilamellar vesicles of varying composition (0.1 mM final lipid concentration) to compare the fluorescence decays of the fluorophores. With both probes, the vesicles were formed as described for DSC, with the difference that hydration was performed with argon-purged MQ-water at 65°C and the samples then vortexed briefly, saturated with argon and sonicated for 10 min at 65°C (bath sonicator; Branson). Before fluorescence measurements, the samples were kept in the dark at room temperature overnight. The fluorescence decays were recorded at 23°C with a FluoTime 200-spectrofluorimeter with a PicoHarp 300E time-correlated single photon-counting module (PicoQuant, Berlin, Germany). Both tPA-Cer and tPA were excited with a 298-nm LED laser source and the emission collected at 430 nm. The samples were kept under constant stirring during the measurements. Data were analyzed with the FluoFit Pro-software obtained from PicoQuant.

Results

Thermotropic properties of binary bilayers of PCer and the SM analogs

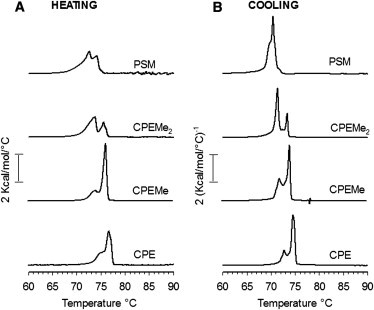

At the outset, the influence of the SM headgroup size on SM/ceramide interactions was studied with DSC on equimolar binary mixtures of PCer and the SM analog (Fig. 1). The heating thermogram for the PSM/PCer-bilayers showed a bimodal melting transition around 70–75°C (Fig. 1 A). Separate transitions for PSM (at 41°C (18,33)) and PCer (at ∼90°C (34,35)) were not observed (data not shown), indicating absence of phase separation or pure components. Although PSM and PCer did not phase-separate, their mutual miscibility was not ideal, as indicated by the complex phase transition with modest cooperativity. In several preceding studies, one broad transition peak of low cooperativity appearing at ∼72°C has been reported for equimolar PSM/PCer-bilayers (18,33,36). However, when Busto et al. (18) analyzed the third consecutive heating scan of an equimolar mixture of PSM and PCer with DSC, the peak at 72°C was deconvoluted into two components with presumable differences in the relative PSM/PCer-ratios.

Figure 1.

Thermotropic properties of bilayers prepared from SM analog and PCer (1:1, by mol). Representative DSC-thermograms of the last heating (A) and cooling (B) scans of 12 consecutive cycles (1°C/min) of two independently repeated experiments are shown. For clarity, only the temperature range around the gel-to-fluid transition is shown omitting long stretches of uneventful baseline.

This could explain why, for this article, we observed a separation of the melting transition into two peak-heights when the binary mixture were heated and cooled until apparent equilibrium (up to 12 cycles). Similarly to PSM, all the SM analogs formed complex gel phases with PCer. Systematic removal of the methyl units from the PSM-headgroup caused a gradual shift of the melting profile to slightly higher temperature with CPE/PCer-bilayers melting at ∼73–78°C (Fig. 1 A). Slight changes in the melting profiles were also observed, presumably stemming from differences in the relative SM analog/PCer-ratios in the gel phases. However, the differences in the transition temperatures of the binary mixtures observed here are surprisingly low compared to the differences in the Tm of the pure SM analogs (varying between 41 and 65°C for PSM and the analogs as deduced from DPH-anisotropy (26)). This suggests that the SM analogs interacted with PCer rather similarly to PSM despite the differences in their headgroup size. The thermotropic behavior for all the binary mixtures was similar in the heating and cooling scans (Fig. 1 B), although slight differences in the relative melting profiles of the complex gel phases were observed. The melting transitions also occurred at a slightly lower temperature (∼2°C) in the cooling scans compared to the heating scans.

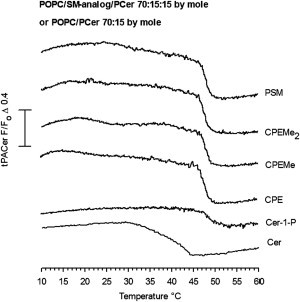

Formation and melting of ceramide-enriched domains

Next, we sought to determine if the similarities in the PCer/SM analog interactions observed with DSC remained in a more complex fluid POPC-bilayer. For that, the formation and subsequent melting of ceramide-rich domains was studied by 7SLPC-induced fluorescence quenching of tPA-Cer (36,37). In a bilayer composed of POPC, PSM, and PCer (70:15:15, by mol), where coexistence of a POPC-rich fluid and a PCer-rich gel phase are expected (19), a clear domain melting could be detected, with an end-melting temperature of ∼50°C (Fig. 2). We have previously obtained a similar result with both tPA-Cer and tPA-SM (37). The domain formed by PCer in POPC (15:75, by mol) in the absence of PSM was less stable (∼8°C; Fig. 2). This end-melting temperature of the PCer domain in the POPC bilayer agrees nicely with similar results in a published phase diagram for POPC and PCer (38). When PSM was replaced with the SM analogs, nearly identical quenching curves were obtained, which indicates that reducing the size of the SM headgroup did not markedly affect the ability of SM analogs to interact with PCer and form ordered domains of relatively high melting temperature.

Figure 2.

Formation of ceramide-rich domains in laterally heterogeneous bilayers. The ability of the SM analogs to interact with PCer to form ordered gel phase domains was determined by 7SLPC-induced fluorescence quenching of tPA-Cer as a function of temperature. The F0 samples had the following compositions: 70 nmol POPC, 15 nmol SM analog, 15 nmol PCer, and 1 nmol tPA-Cer. One system consisted only of 70 nmol POPC and 15 nmol PCer and 1 nmol tPA-Cer. In the composition which also included the quencher (F-samples), 30 nmol 7SLPC replaced an equal amount of POPC. The curves are representative of at least two separate experiments for each composition.

To further test the effects of co-lipid headgroup size on PCer interactions in the POPC bilayer, we also included C-1-P in the comparison. As seen in Fig. 2, an almost identical domain-melting curve was seen the ordered phospholipid was C-1-P instead of any of the SM analogs. The affinity of ceramide for these ordered domains appear to be similar despite the differences in the SM analog headgroup size, because the ΔF/F0 amplitude (before and after complete melting) of the melting profiles remained virtually identical in the presence of the different SM analogs. The exception was the C-1-P system, which showed smaller amplitude of F/F0. It is possible that the lower apparent affinity of PCer for C-1-P in the POPC bilayer was a result of the net negative charge on the phosphate.

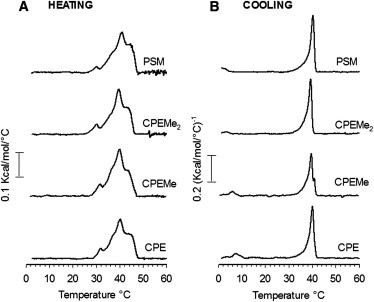

Thermotropic behavior of the interaction between ceramide and SM analogs in a fluid bilayer

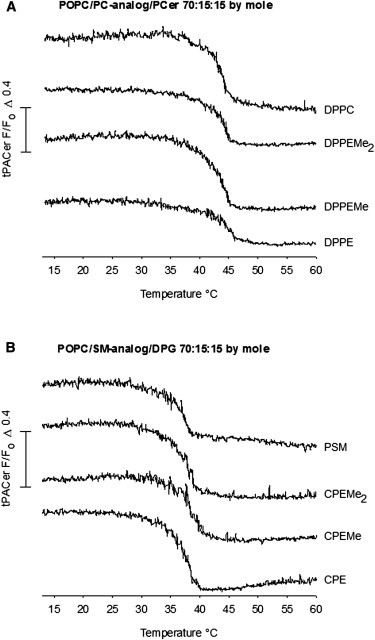

Although the quenching results showed virtually no differences in the ability of the SM analogs to interact with PCer to form ordered phases in POPC bilayers, we wanted to study these interactions with a probe-free method as well. To that end, we performed DSC studies with POPC/SM analog/PCer-bilayers. It is important to note that a detailed understanding of each of the components of the broad, complex transitions that were observed (Fig. 3) is difficult, because we cannot know the composition of each component undergoing phase melting. Nevertheless, our goal was not to obtain a detailed description of the PCer/SM analog interaction, but merely to compare the different analogs. In this context, the results from the DSC supported the conclusion from the previous quenching experiments that alterations of the size of the SM headgroup did not markedly affect the interactions with ceramide, because all the bilayers displayed a nearly identical gel melting temperature and profile (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3.

Thermotropic properties ordered domains formed in POPC/SM analog/PCer bilayers (70:15:15, by mol). Representative DSC-thermograms of the last heating (A) and cooling (B) scans (1°C/min) of two independently repeated experiments are shown. For clarity, the high temperature region of the uneventful thermogram baseline has been omitted.

The temperature at which the bilayers were fully in a fluid state (∼49°C) was in good agreement with the end-melting temperature observed by the quenching experiments (Fig. 2 A). The recorded cooling thermograms showed more cooperative transitions than the heating scans (Fig. 3 B), suggesting different thermotropic behavior depending on whether the bilayers underwent melting or recrystallization. However, the highest Tm peak during cooling was nearly identical to that of the heating scan. The cooling scans also showed a small component in the low-temperature region, which shifted to higher temperature with decreasing SM headgroup size (Fig. 3 B). This component could be related to a POPC-rich phase, which becomes thermally stabilized by the analogs with smaller headgroup due to their increasing Tm (26).

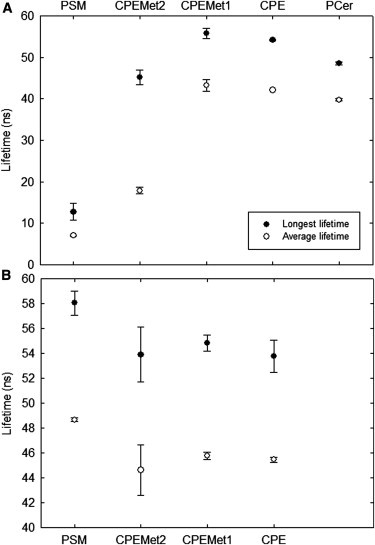

Effects of SM analog/PCer interactions on tPA-Cer lifetimes

tPA is widely used to explore ceramide-rich phases in lipid bilayers due to its partitioning into ordered and gel phases in which it reports longer lifetimes than in less compact fluid phases (19,39–41). In analogy with the sensitivity of tPA to the order in its surroundings, the lifetimes of tPA-Cer should also vary in bilayers of different molecular order. However, to the best of our knowledge, no intensity decays have been measured with tPA-Cer. Therefore, we sought to initially determine whether the linkage of tPA to a sphingosine moiety altered its ability to characterize ordered and gel phases. For that, time-resolved fluorescence decay of tPA and tPA-Cer were measured in a few control bilayers (see Table S1 in the Supporting Material). Although some variation among the individual lifetime components, fractional intensities, and fractional amplitudes of tPA and tPA-Cer were observed, the results showed that tPA-Cer behaved similarly to tPA, reporting significantly longer lifetimes in mixtures where ordered or gel phases were expected to be present. This is in agreement with a previous study that showed nearly identical lifetimes for free tPA and trans-parinaroyl phosphatidylcholines (42).

Next, we examined lifetimes of tPA-Cer in bilayers containing the SM analogs to further explore the properties of the ordered phases they formed. Binary mixtures (85:15 by mol) of POPC and SM analog or PCer were studied (Fig. 4 A). In POPC/PCer-bilayers, tPA-Cer reported a tightly packed gel phase, because of the very long lifetime component (∼49 ns). This finding is consistent with previously reported phase state of POPC/PCer at this composition and temperature the (38,40). In the POPC/PSM system, the longest lifetime component was significantly shorter, indicating the absence of a gel phase. This also agrees with the phase diagram of de Almeida et al. (43).

Figure 4.

tPA-Cer fluorescence lifetimes in bilayers containing the SM analogs. The longest lifetime component (solid circles) and average lifetime (open circles) of tPA-Cer (1 mol %) were measured at 23°C in bilayers composed of (A) POPC/PCer or POPC/SM analog (85:15 by mol), and (B) POPC/SM analog/PCer (70:15:15). Each value is the average from three separate experiments ± SD.

For all binary mixtures with the SM analogs, the longest lifetime component was remarkably longer than with PSM, showing that the reduction in the SM headgroup size led to a higher ability to induce gel phase formation. This finding is consistent with the Tm reported for the pure SM analogs, showing that headgroup properties efficiently affect lateral packing and gel phase stabilization (26). However, the average lifetime measured for the CPEMe2-containing binary bilayers was shorter than with the other SM analogs, possibly suggesting closeness to a phase transition at the measured temperature. When SM analogs and PCer were allowed to interact in a POPC bilayer (15:15:70 by mol), tPA-Cer reported very long lifetime components for all systems, indicating the gel-like nature of the ordered domains formed (Fig. 4 B).

Role of chain-chain interactions and hydrogen bonding in phospholipid-ceramide interactions

Because all the SM analogs appeared equally able to interact with PCer despite the reduced headgroup size, we sought to explore the possible role of the chain-chain interactions and interfacial hydrogen bonds in stabilization of the SM-ceramide interactions. For that, we used the corresponding glycerol-based PC-analogs with identical reduction in headgroup size as in the SM analogs, and studied the formation and melting of laterally segregated domains formed by the PC-analogs and PCer. The pure hydrated PC-analogs, i.e., DPPC, DPPEMe2, DPPEMe, and DPPE display constantly lower gel-to-fluid transition temperatures than the SM analogs (varying between 41 and 61.5°C for DPPC and the analogs as deduced from DPH-anisotropy (26)). The ordered domains formed between PC analogs and PCer in the POPC bilayers had a similar thermostability, despite changes in their headgroup properties (Fig. 5 A). Compared to the domains formed by the SM analogs and PCer (Fig. 2 A), the saturated PC-containing domains showed lower domain melting temperatures (4–5°C lower). The slightly higher thermostability of SM analog/PCer domains, compared to PC analog/PCer domains, could be due to stabilization by interlipid hydrogen bonding among the sphingolipids.

Figure 5.

Detection of domain melting in the presence of PC-analogs or DPG. The thermal stability of laterally segregated domains formed by the PC-analogs and PCer, or by the SM analogs and DPG, was determined by 7SLPC-induced fluorescence quenching of tPA-Cer as a function of temperature. The bilayers were composed of (A) POPC/PC-analog/PCer (70:15:15 mol %) and (B) POPC/SM analog/DPG (70:15:15 mol %). In quenched curves, the composition was (A) POPC/7SLPC/PC-analog/PCer (40:30:15:15 mol %) and (B) POPC/7SLPC/SM analog/DPG (40:30:15:15 mol %). Representative quenching curves from two reproducible experiments are shown.

To further study the role of chain-chain interactions and hydrogen bonding in stabilization of interlipid interactions, we decided to investigate the thermal stability of the SM analogs’ interactions with DPG. DPG, like ceramide, also has a small polar hydroxyl, but lacks the hydrogen bond–forming properties of ceramides. It was observed that the size of the SM analog headgroup did not markedly affect the thermal stability of the laterally segregated domains formed with DPG (Fig. 5 B). Compared to the SM analog/PCer-containing mixtures, the SM analog/DPG-ordered domains melted at a lower temperature, which could reflect the fact that a pure DPG gel phase has a significantly lower melting temperature compared to PCer (below 70°C for DPG (44,45) versus ∼90°C for PCer (34,35)).

Discussion

SMs and ceramides are known to interact favorably with each other, forming a highly ordered ceramide-enriched gel phase in bilayer membranes (17–20,36,46–48). In this study, we explored the effect of the PSM headgroup size on this interaction by using SM analogs with decreasing numbers of methyl groups in the headgroup (CPEMe2, CPEMe, and CPE). We have previously characterized the bilayer properties of these SM analogs and found that a decrease in the PSM headgroup size resulted in increased temperature for the main phase transition, decreased molecular area, and increased acyl-chain order (26). Moreover, in line with the umbrella model first proposed by Huang and Feigenson (24), we observed that a decrease in the SM headgroup size resulted in a lower ordering effect of cholesterol on the acyl chains, a decrease in the affinity of cholesterol for bilayers containing the SM analogs, and a decrease in the amount of cholesterol in ordered domains formed by the analogs (26).

Ceramide is a simple sphingolipid which, like cholesterol, has a large hydrophobic body and a small polar headgroup. Thus, the size of the SM headgroup could also be expected to be of importance for its interaction with ceramide in bilayers, shielding ceramide from unfavorable interactions with the aqueous environment. The increase in the acyl-chain order of the SM analogs observed previously (26) agrees with our present observations of a higher gel-inducing capability of the analogs with smaller headgroup in fluid POPC-bilayers (Fig. 4 A and see Table S2). However, as evidenced by the DSC data (Figs. 1 and 3), the fluorescence quenching data (Fig. 2), and lifetime analysis of tPA-Cer (Fig. 4 B, and see Table S2) in bilayers containing the SM analogs and PCer, SM headgroup size was not crucially important for SM-ceramide interactions in contrast to the notable effects observed for cholesterol interactions (26). PCer was even able to form ordered domains with C-1-P, which lacks the choline moiety altogether, and has a negative net charge in the headgroup (Fig. 2). Our results strongly suggest that all the analogs with altered headgroup size formed ceramide-enriched domains that had characteristics similar to those of PSM/ceramide.

According to the phase diagram of Castro et al. (19), the POPC/PSM/PCer 70:15:15-mixture used in this study should exhibit coexistence of a POPC-rich fluid phase and a PCer-rich gel phase at 24°C. Moreover, previously reported thermograms of equimolar binary mixtures of PSM and PCer suggest absence of a PSM-rich/PCer-poor gel phase (18,33,36), which is also indicated by our DSC results (Fig. 1). Loss of the favorable interaction between PCer and the SM analogs could be assumed to result in lower miscibility of PCer with the SM analogs, and increased segregation of these lipids, but this is clearly not the finding in our study. The DSC data strongly suggested that the SM analogs and PCer did not segregate from each other into different phases in the bilayers (Figs. 1 and 3), indicating that SM analog headgroup properties were not dramatically affecting their mutual interaction. However, in a recent molecular-dynamics-simulation study, calculations suggested that the umbrella effect of SM becomes significant in SM/ceramide binary bilayers at ceramide concentrations above 50% (23). This concentration dependency would then agree with our findings, because our SM analog/PCer molar ratio never exceeded a 1:1 molar ratio. However, we can still conclude that PCer interaction with SM analogs differ significantly from that observed with cholesterol, because even at 1:1 stoichiometry of cholesterol/SM analog, the headgroup size/property has dramatic effects on sterol/SM analog interaction (49).

Because PCer could form ordered domains with both SM analogs (Fig. 2), and with analogous PC analogs (Fig. 5 A), and because DPG could form ordered domains with SM analogs (Fig. 5 B), we may conclude that the ordered nature of the acyl-chain region of both PCer/DPG and the phospholipid analogs must have contributed positively to their mutual interaction. Because the saturated lipids were interacting in a POPC bilayer, the association of PCer or DPG with ordered phospholipids was entropically favored. This entropic contribution is likely to be dominant for controlling interactions among the saturated lipid species. Indeed, when Wang and Silvius (17) studied the partitioning of sphingolipids with varying headgroups into ordered domains in bilayer membranes, they observed that regardless of the polar head structure, the sphingolipids were enriched in ordered phases. They concluded that the affinity of the sphingolipids for ordered phases rests primarily in the nature of their ceramide moiety, rather than on special features of the headgroup.

Hydrogen bonding is likely to be less significant, because DPG/SM analog interaction, or PCer/PC analog interactions, were not dramatically different from that seen with PCer/SM analog interaction, even though the latter system should have more extensive interlipid hydrogen bonding compared to the situation with DPG or PC analogs (21–23,50). However, a clue to the role of hydrogen bonding for PCer/phospholipid interaction can perhaps be seen in the results presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 5 A. A 5°C destabilization of the thermostability of the ordered domains was seen, when SM analogs were replaced with PC analogs. This difference is likely to be due to differing hydrogen-bonding properties in the two otherwise comparable systems. Our recent observations that disruption of the hydrogen bonding at the ceramide’s amide group by methylation results in significantly reduced ability of ceramide to interact with SM (33) suggest that interlipid hydrogen bonding has some stabilizing contribution to the mutual interactions between PCer and PSM.

Apparently, due to its irregular shape, cholesterol cannot form similar attractive forces with SM the way PCer can, and therefore the SM headgroup becomes more important in stabilizing SM/cholesterol interactions. In addition, the inherent affinity of SMs and ceramide for each other, which in the light of this study seems to be independent of a possible umbrella effect mediated by the SM headgroup, also partially explain the observation that ceramides at certain concentrations are capable of displacing cholesterol from SM-rich environments (20,37,51,52).

Conclusions

In this study we demonstrated that decreasing the SM headgroup size by systematic removal of methyl groups from its phosphocholine moiety did not result in notable differences in the formation, thermostability, and molecular order of SM/ceramide-rich domains. Although reduction in the size of the SM headgroup would be expected to result in less efficient shielding of ceramide from unfavorable interactions with the aqueous environment, any destabilizing effect on SM-ceramide interactions arising from a reduced headgroup size was probably counterbalanced by the inherent affinity of these two sphingolipids for each other.

Extensive hydrogen-bonding networks, as well as the increased acyl-chain packing of the SM analogs caused by the smaller headgroups, were likely to compensate for any destabilizing effects stemming from the modified SM headgroup. Based on our results, it appears that the SM headgroup is not as crucial for SM/ceramide interactions as it is for the SM/cholesterol. Although ceramide can stabilize SM-rich phases by reducing the steric repulsion among the SM headgroups, the SM headgroup does not appear to strongly participate in enabling the strong interactions between SM and ceramide.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shishir Jaikishan for technical help.

Financial supports from the Sigrid Juselius Foundation (to J.P.S.), Åbo Akademi University (to J.P.S. and T.M.), National Doctoral Program in Informational and Structural Biology (to T.M.), Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa (to T.M.), Magnus Ehrnrooth foundation (to J.P.S. and T.M.), Oskar Öflund Foundation (to T.M.), Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland (to T.M.), Grant-in-Aid for Science Research on Priority Areas No. 16073222 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and a Matching Fund Subsidy for a Private University, Japan (to S.K.), are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Ibai Artetxe’s present address is Unidad de Biofísica (Centro Mixto CSIC-UPV/EHU), and Departamento de Bioquímica, Universidad del País Vasco, Aptdo. 644, 48080 Bilbao, Spain.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Zwaal R.F., Roelofsen B., van Deenen L.L. Organization of phospholipids in human red cell membranes as detected by the action of various purified phospholipases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1975;406:83–96. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons K., van Meer G. Lipid sorting in epithelial cells. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6197–6202. doi: 10.1021/bi00417a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Meer G., Stelzer E.H., Simons K. Sorting of sphingolipids in epithelial (Madin-Darby canine kidney) cells. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:1623–1635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simons K., Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike L.J. Rafts defined: a report on the Keystone Symposium on lipid rafts and cell function. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:1597–1598. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E600002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levade T., Jaffrézou J.P. Signaling sphingomyelinases: which, where, how and why? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1438:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hannun Y.A., Obeid L.M. Ceramide: an intracellular signal for apoptosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:73–77. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannun Y.A. The sphingomyelin cycle and the second messenger function of ceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:3125–3128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannun Y.A. Functions of ceramide in coordinating cellular responses to stress. Science. 1996;274:1855–1859. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannun Y.A., Luberto C. Ceramide in the eukaryotic stress response. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Blitterswijk W.J., van der Luit A.H., Borst J. Ceramide: second messenger or modulator of membrane structure and dynamics? Biochem. J. 2003;369:199–211. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang W.C., Chen C.L., Lin C.F. Apoptotic sphingolipid ceramide in cancer therapy. J. Lipids. 2011;2011:565316. doi: 10.1155/2011/565316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holopainen J.M., Subramanian M., Kinnunen P.K. Sphingomyelinase induces lipid microdomain formation in a fluid phosphatidylcholine/sphingomyelin membrane. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17562–17570. doi: 10.1021/bi980915e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fanani M.L., De Tullio L., Maggio B. Sphingomyelinase-induced domain shape relaxation driven by out-of-equilibrium changes of composition. Biophys. J. 2009;96:67–76. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.141499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Tullio L., Maggio B., Fanani M.L. Sphingomyelinase acts by an area-activated mechanism on the liquid-expanded phase of sphingomyelin monolayers. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800127-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanani M.L., Härtel S., Maggio B. Bidirectional control of sphingomyelinase activity and surface topography in lipid monolayers. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3416–3424. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75341-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang T.Y., Silvius J.R. Sphingolipid partitioning into ordered domains in cholesterol-free and cholesterol-containing lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2003;84:367–378. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74857-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busto J.V., Fanani M.L., Alonso A. Coexistence of immiscible mixtures of palmitoylsphingomyelin and palmitoylceramide in monolayers and bilayers. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2717–2726. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro B.M., de Almeida R.F., Prieto M. Formation of ceramide/sphingomyelin gel domains in the presence of an unsaturated phospholipid: a quantitative multiprobe approach. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1639–1650. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sot J., Ibarguren M., Alonso A. Cholesterol displacement by ceramide in sphingomyelin-containing liquid-ordered domains, and generation of gel regions in giant lipidic vesicles. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3230–3236. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pascher I. Molecular arrangements in sphingolipids. Conformation and hydrogen bonding of ceramide and their implication on membrane stability and permeability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;455:433–451. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niemelä P., Hyvönen M.T., Vattulainen I. Structure and dynamics of sphingomyelin bilayer: insight gained through systematic comparison to phosphatidylcholine. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2976–2989. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metcalf R., Pandit S.A. Mixing properties of sphingomyelin ceramide bilayers: a simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:4500–4509. doi: 10.1021/jp212325e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang J., Feigenson G.W. A microscopic interaction model of maximum solubility of cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2142–2157. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77369-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J., Buboltz J.T., Feigenson G.W. Maximum solubility of cholesterol in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1417:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Björkbom A., Róg T., Slotte J.P. Effect of sphingomyelin headgroup size on molecular properties and interactions with cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3300–3308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maula T., Westerlund B., Slotte J.P. Differential ability of cholesterol-enriched and gel phase domains to resist benzyl alcohol-induced fluidization in multilamellar lipid vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:2454–2461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramstedt B., Slotte J.P. Interaction of cholesterol with sphingomyelins and acyl-chain-matched phosphatidylcholines: a comparative study of the effect of the chain length. Biophys. J. 1999;76:908–915. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77254-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaikishan S., Björkbom A., Slotte J.P. Sphingomyelin analogs with branched N-acyl chains: the position of branching dramatically affects acyl chain order and sterol interactions in bilayer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:1987–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nussbaumer P., Hornillos V., Ullrich T. An efficient, one-pot synthesis of various ceramide 1-phosphates from sphingosine 1-phosphate. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2008;151:125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen R., Barenholz Y., Dagan A. Preparation and characterization of well defined D-erythro sphingomyelins. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1984;35:371–384. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(84)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuklev D.V., Smith W.L. Synthesis of four isomers of parinaric acid. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2004;131:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maula T., Kurita M., Slotte J.P. Effects of sphingosine 2N- and 3O-methylation on palmitoyl ceramide properties in bilayer membranes. Biophys. J. 2011;101:2948–2956. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah J., Atienza J.M., Shipley G.G. Structural and thermotropic properties of synthetic C16:0 (palmitoyl) ceramide: effect of hydration. J. Lipid Res. 1995;36:1936–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sot J., Aranda F.J., Alonso A. Different effects of long- and short-chain ceramides on the gel-fluid and lamellar-hexagonal transitions of phospholipids: a calorimetric, NMR, and x-ray diffraction study. Biophys. J. 2005;88:3368–3380. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Björkqvist Y.J., Nyholm T.K., Ramstedt B. Domain formation and stability in complex lipid bilayers as reported by cholestatrienol. Biophys. J. 2005;88:4054–4063. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alanko S.M., Halling K.K., Ramstedt B. Displacement of sterols from sterol/sphingomyelin domains in fluid bilayer membranes by competing molecules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1715:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsueh Y.W., Giles R., Thewalt J. The effect of ceramide on phosphatidylcholine membranes: a deuterium NMR study. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3089–3095. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75650-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castro B.M., Silva L.C., Prieto M. Cholesterol-rich fluid membranes solubilize ceramide domains: implications for the structure and dynamics of mammalian intracellular and plasma membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22978–22987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva L., de Almeida R.F., Prieto M. Ceramide-platform formation and -induced biophysical changes in a fluid phospholipid membrane. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2006;23:137–148. doi: 10.1080/09687860500439474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva L.C., de Almeida R.F., Prieto M. Ceramide-domain formation and collapse in lipid rafts: membrane reorganization by an apoptotic lipid. Biophys. J. 2007;92:502–516. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolber P.K., Hudson B.S. Fluorescence lifetime and time-resolved polarization anisotropy studies of acyl chain order and dynamics in lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2800–2810. doi: 10.1021/bi00513a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Almeida R.F., Fedorov A., Prieto M. Sphingomyelin/phosphatidylcholine/cholesterol phase diagram: boundaries and composition of lipid rafts. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2406–2416. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.López-García F., Villalaín J., Gómez-Fernández J.C. Diacylglycerol, phosphatidylserine and Ca2+: a phase behavior study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1190:264–272. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.López-García F., Villalaín J., Quinn P.J. The phase behavior of mixed aqueous dispersions of dipalmitoyl derivatives of phosphatidylcholine and diacylglycerol. Biophys. J. 1994;66:1991–2004. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80992-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massey J.B. Interaction of ceramides with phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin and sphingomyelin/cholesterol bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1510:167–184. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sot J., Bagatolli L.A., Alonso A. Detergent-resistant, ceramide-enriched domains in sphingomyelin/ceramide bilayers. Biophys. J. 2006;90:903–914. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boulgaropoulos B., Arsov Z., Pabst G. Stable and unstable lipid domains in ceramide-containing membranes. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2160–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reference deleted in proof.

- 50.Li L., Tang X., Yappert M.C. Conformational characterization of ceramides by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2067–2080. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75554-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiantia S., Kahya N., Schwille P. Raft domain reorganization driven by short- and long-chain ceramide: a combined AFM and FCS study. Langmuir. 2007;23:7659–7665. doi: 10.1021/la7010919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiantia S., Kahya N., Schwille P. Effects of ceramide on liquid-ordered domains investigated by simultaneous AFM and FCS. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4500–4508. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.081026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.