Abstract

Mathematical modeling has established its value for investigating the interplay of biochemical and mechanical mechanisms underlying actin-based motility. Because of the complex nature of actin dynamics and its regulation, many of these models are phenomenological or conceptual, providing a general understanding of the physics at play. But the wealth of carefully measured kinetic data on the interactions of many of the players in actin biochemistry cries out for the creation of more detailed and accurate models that could permit investigators to dissect interdependent roles of individual molecular components. Moreover, no human mind can assimilate all of the mechanisms underlying complex protein networks; so an additional benefit of a detailed kinetic model is that the numerous binding proteins, signaling mechanisms, and biochemical reactions can be computationally organized in a fully explicit, accessible, visualizable, and reusable structure. In this review, we will focus on how comprehensive and adaptable modeling allows investigators to explain experimental observations and develop testable hypotheses on the intracellular dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton.

Introduction

The renowned physicist Freeman Dyson tells the story (1) of a transformative meeting in 1953 with Enrico Fermi, in which the young Dyson presented a new theoretical treatment that he felt could explain Fermi’s experimental findings. Fermi was, to say the least, not convinced. “In desperation I asked Fermi whether he was not impressed by the agreement between our calculated numbers and his measured numbers. He replied, ‘How many arbitrary parameters did you use for your calculations?’ I thought for a moment about our cut-off procedures and said, ‘Four.’ He said, ‘I remember my friend Johnny von Neumann used to say, with four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk.’ With that, the conversation was over. I thanked Fermi for his time and trouble, and sadly took the next bus back to Ithaca to tell the bad news to the students.”

The actin cytoskeleton drives many cellular processes including structural support within cells, cell migration, endocytosis, and cytokinesis. How should modelers approach such a complex system? Fermi’s philosophy that the best mathematical model is one with a minimal number of equations and parameters has pervaded physics and, by extension, biophysics. Indeed, the model that serves as the foundation of our thinking about how actin polymerization can dynamically control cell shape and motility is conceptually elegant: the Brownian ratchet model (2). Building off a previously published formulation (3), Mogilner and Oster used a minimal number of equations to show how polymerization of elastic filaments generates protrusive force at membranes. The impact of the Brownian ratchet idea demonstrates the power of using conceptual models to describe biological systems. The Mogilner lab recently published a review highlighting the benefits of conceptual models for understanding actin-dependent cellular processes (4).

However, it is likewise clear that, despite von Neumann’s assertion, a mathematical model with five parameters or six equations will never be able to explain how elephants become elephants or why elephants do all that they do—elephants are just too complicated (see, however, Mayer et al. (5)). We also know that the actin cytoskeleton is pretty complicated. It is a finely tuned biochemical and mechanical system in which many proteins interact to control actin polymerization, depolymerization, and/or stabilization (6–11). Many of these mechanisms have been characterized by in vitro biochemical measurements or live-cell quantitative fluorescence microscopy measurements. However, such measurements can only look at the roles of one or two actin-binding proteins at a time. Thus, investigators tend to focus on defining a critical and central function or activity for their favorite molecule. As shown in Table S1 in the Supporting Material, many actin regulatory proteins have been identified, and in many cases, kinetic or binding parameters have been measured. This table, which does not claim to be comprehensive, catalogs 131 molecules that interact with actin. It is clear that focusing on just one or two players in complex nonlinear interaction networks can be a flawed strategy—the apparent function of any one molecule may depend on the state of other molecules in the system. But biologists strive to tease out the interactions of each molecule in these networks both to address fundamental cellular mechanisms and to identify therapeutic targets or strategies. To fully understand how these molecules orchestrate the many actin-dependent cellular processes clearly requires comprehensive detailed models with too many parameters for Fermi to have tolerated. Happily, however, quantitative experimental data can constrain these parameters, and live-cell microscopy can be used to validate model predictions.

Happily also, there are software tools that make modeling and simulation readily accessible to the actin biology and biophysics community (12) (for a rather complete list go to http://sbml.org/SBML_Software_Guide/SBML_Software_Matrix). Our lab has developed the Virtual Cell software system (VCell) (13–15) (http://vcell.org) that enables the construction of models composed of biochemical reactions, membrane fluxes, and molecular diffusion and flow. It provides capabilities for stochastic or deterministic simulations for either compartmental models (i.e., well mixed) or spatial reaction/diffusion models in realistic geometries. Importantly, VCell has a graphical user interface for building reaction networks, and models are accessed through a central database; these capabilities support the visualization and reuse of complex models, as would be needed for the actin system. Finally, the database allows for models to be opened to the entire community; thus, public VCell models can serve as a starting point for construction of new models based on a core set of common interactions.

In this review, we will describe how quantitative experimental data for many molecules found in Table S1 has fed models of actin polymerization and how model simulations have been used to both analyze experimental results and prompt the design of new experiments. It is clear that we cannot, within the limited scope of this review, cover all the actin modeling studies that have utilized detailed experimental data, and we apologize for the omission of many such important studies. Our goal, however, is to use examples of increasing complexity to illustrate that the close interplay between mathematical model and quantitative experiment can produce an increasingly deep understanding of how the dynamic actin cytoskeleton is marshaled to control diverse cell biological processes.

Building a foundation

Early actin-cytoskeleton modeling aimed to mathematically explain the nature of the monomeric G-actin-to-filamentous-F-actin transition observed in experiments, using thermodynamics to describe polymer formation (16). In 1961, Oosawa and Kasai developed such a model based on experimental results from their lab (17). They found that polymerization of a pool of actin monomers was both salt- and monomer-concentration dependent, and that a critical concentration of G-actin existed above which polymerization would occur in solution. In another foundational modeling study, published in 1976 (18), Wegner mathematically described actin treadmilling—the steady-state translation of actin filaments via addition of G-actin primarily to the filament barbed end while dissociation occurs primarily at the pointed end. Wegner derived a set of kinetic equations that were fit to experimental results to describe ATP- or ADP-bound actin polymerization; the model explained the discovery that polymerization was dependent on the nucleotide state of the actin subunits (19). Although both the Wegner and Oosawa studies set the stage for modern actin cytoskeletal modeling, their efforts were limited in that kinetic rate data of actin polymerization had not yet been explicitly measured.

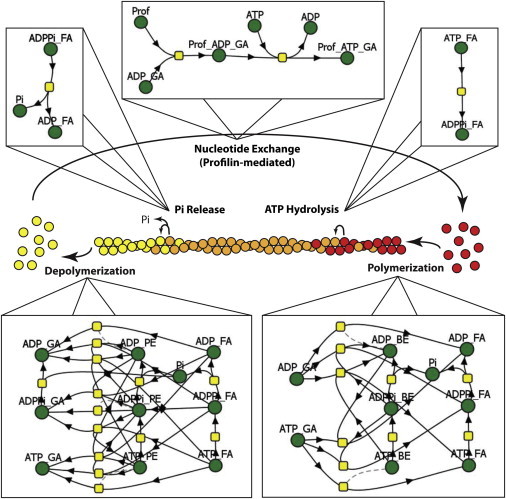

Technological advances, especially the pyrene-labeled actin polymerization assay, subsequently enabled the measurement of actin monomer-actin filament binding rates in solution (20–24). These experimental measurements served two purposes: 1), they provided an initial glimpse into the mechanism of filament treadmilling; and 2), they laid the foundation upon which subsequent quantitative models have been constructed. As shown in Fig. 1, actin treadmilling is conceptually simple yet mathematically complex because of the number of reactions and rates needed to accurately describe the process. The cartoon hides the fact that actin in all three nucleotide forms (ATP, ADP·Pi, or ADP) can bind to either the barbed or pointed ends and that binding is fully reversible. Ultimately, taking advantage of detailed experimentally measured data, Vavylonis et al. built a quantitative discrete model of actin polymerization (25). This model could be validated and refined via new in vitro experiments where single-filament dynamics are visualized via total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (26). This combination of modeling and experiment produced a complete analysis of all the steps depicted in Fig. 1, providing the basis for further quantitative investigation of how actin treadmilling is regulated.

Figure 1.

Accurate modeling of simple actin treadmilling requires complex mathematical descriptions. The cartoon in the center summarizes the overall process. During actin filament treadmilling, ATP-bound actin monomers (red) bind to the barbed end of the filament; as the filament ages, the ATP on each subunit is hydrolyzed, forming ADP-Pi-bound actin (orange); eventually, the Pi is released, forming ADP-bound actin subunits, which then depolymerize from the pointed end. ADP-bound actin monomers then undergo nucleotide exchange to return to their ATP-bound state. As useful as it may be to summarize the biology, this cartoon hides the details that would be required to model this system. VCell reaction network diagrams for each process (barbed-end turnover, pointed-end turnover, ATP hydrolysis, Pi Release, and profilin-mediated nucleotide exchange) are shown to demonstrate the mathematical complexity required for proper description of actin dynamics. In the Virtual Cell reaction diagrams, green balls represent molecular species (i.e., variables) and yellow squares represent reactions, each with a corresponding rate expression. The figure displays only one example of an infinite number of filament lengths and subunit nucleotide-state arrangements. FA, F-actin; GA, G-actin; BE, barbed end; PE, pointed end; Prof, profilin; Pi, inorganic phosphate.

Filament branching mediated by Arp2/3 complex

Actin polymers can form a highly branched network near the plasma membrane (27,28), with dynamics that control lamellipodial protrusion and retraction. This network is formed and maintained by the Arp2/3 complex (29), which nucleates new filaments after activation by nucleation-promoting factors. In an attempt to direct experimentalists toward an understanding of Arp2/3 complex branching, Carlsson constructed a model to evaluate the dependence of actin-network growth on protein concentration and opposing forces (30). That model determined that growth of the dendritic actin network was dependent not only on protein concentrations and forces, but also on the mechanism by which the Arp2/3 complex nucleated new filaments. Existing experimental results were unclear as to whether the Arp2/3 complex functioned as a filament side branch nucleator (31,32) or a barbed-end branch nucleator (33). To address this question, Carlsson and colleagues built a model to test actin nucleation and polymerization while accounting for either end or side branching (34). Model predictions indicated that side branching is the mechanism by which actin-filament nucleation occurs; by using the model to analyze the experiments, they showed that data used to argue for end branching were actually more consistent with side branching.

These results were supported by another model used to investigate potential rate-limiting steps of filament nucleation (35). Schaus and Borisy constructed a 2-dimensional discrete model that accounted for the essential dynamic properties of the network (36); stochastic simulations predicted that self-organization of the dendritic network at the leading edge of the lamellipodium emerged from dynamic properties included in the model and that no additional mechanical or biochemical factors were needed to explain experimentally observed branching patterns. In another study using available kinetic data, Schaus and Borisy also demonstrated that branched networks push membranes forward using Brownian-ratchet mechanics (37). As experimental data on the role of the Arp2/3 complex in branching became available, these studies showed that modeling could demonstrate how branched networks formed and evolved at the leading edge of motile cells.

The activities of actin-binding proteins: the whole is not always the sum of its parts

As the study of actin dynamics has expanded, the important roles of actin-binding proteins (ABPs) have emerged. As summarized in Table S1, ABPs affect both G-actin and F-actin. Proteins interact with G-actin to mediate monomer sequestration, polymerization, and ADP-to-ATP nucleotide exchange; in addition to branching mediated by Arp2/3, F-actin-ABP interactions can promote filament stabilization or destabilization, bundling, and capping. Additionally, there are upstream regulatory proteins that modulate the activity of ABPs. Building a mathematical model that accurately predicts cell biological outputs is also likely to require knowledge of how these molecular species are distributed within the complex cellular geometry.

Thymosin-β4 (Tβ4) sequesters G-actin, allowing cells to maintain a pool of monomeric actin (38). In a study testing the effect of Tβ4 on cell migration, the direction of keratocyte locomotion was controlled by uncaging of Tβ4 (39), where an inactivated form of the protein was photochemically converted to the active form with a laser flash applied to different locations in the cell. VCell was employed to test hypotheses of the effect of Tβ4 uncaging on actin dynamics and to analyze the distribution of free G-actin before and after uncaging. Model predictions were then experimentally tested. This study demonstrated that by spatially controlling the sequestration of G-actin, cells can control the direction in which they are migrating.

Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoproteins (VASPs) affect filament growth, capping, and bundling (40). VASP regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics was investigated in keratocyte motility (41). Experimental measurements of cell shape, leading edge shape, F-actin distribution, cell velocity, directional persistence, and VASP enrichment were used to create a model of the role of VASP in keratocyte motility. Model predictions and experimental confirmation resulted in a deeper understanding of how VASP affects cytoskeletal arrangement to promote observable cytoskeletal characteristics during migration.

Cortactin is involved in several biological processes requiring regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, including invadopod and podosome formation (42), pathogen and endosome motility (43), and lamellipodial protrusion (44,45). Through a combination of bead-based in vitro experiments and modeling, Siton and colleagues suggested that cortactin functions in Arp2/3-complex branch kinetics by promoting the release of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP)-VCA domains from the Arp2/3 complex after branch formation (46).

ADF/Cofilin regulation of the actin cytoskeleton has been a major focus of computational modeling. An intriguing aspect of cofilin biology is that although some in vitro experimental results demonstrate that it enhances actin depolymerization through either filament severing (47) or acceleration of pointed-end dynamics (48), other in vivo experiments suggest that cofilin enhances actin polymerization (49). Carlsson presented a simplified mathematical model of severing activity, which showed that as long as barbed-end concentration was limiting, as would be the case when barbed-end capping activity is high, cofilin-induced severing would increase overall actin polymerization by increasing the concentration of barbed ends (50). This is an important example of how understanding the role of a particular actin modulatory protein may require consideration of the levels of other activities in the overall system.

Modeling has provided valuable insights into the role of ADF/cofilin in regulating large-scale actin-network dynamics. One study investigated the nucleotide state of growing actin networks and how cofilin activity affected network dynamics (51). Model predictions coupled with experimental observations demonstrated that actin-network growth and filament severing reach a stable dynamical regime in which filament severing by cofilin is the most important factor in actin turnover. Two-dimensional Monte Carlo simulations (52) revealed that the interplay of capping protein, cofilin, and tropomyosin promote self-organization of the actin cytoskeleton underlying lamellipodium and lamellum structure formation, as experimentally defined by Chhabra and Higgs (53). This model predicted that cofilin severing at the leading edge, together with tropomyosin stabilization of longer filaments, resulted in the self-assembly of distinct lamellipodium and lamellum structures, consistent with what is experimentally observed.

The regulation of ADF/cofilin has also been investigated with the aid of experiment-driven modeling. Cofilin is regulated by PIP2, LIM kinase, and slingshot phosphatase (54,55), and has been implicated in generating the initial spike of barbed-end formation after epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor stimulation (56). Tania and colleagues built a model to investigate whether regulation by the three factors mentioned above can account for the initial barbed-end spike within 1 min of EGF stimulation (57). Their model predicted that actin polymerization is dependent on both the PIP2-bound cofilin available for release and the rates of cofilin binding and severing of filaments, balanced with the inactivation of cofilin by LIM kinase and diffusion away from the leading edge. These predictions are experimentally testable and can direct future experiments to resolve the temporal and spatial dynamics of cofilin after EGF stimulation.

Formins are another class of ABPs that behave primarily as nucleators of actin polymerization. Pollard and Vavylonis have pioneered initial modeling efforts into understanding formin activity. In a study that took advantage of measured formin kinetics (58–63), Vavylonis et al. used mechanistic modeling to determine how FH1/FH2 domains promote actin polymerization (64). The authors determined that FH1 domains transfer bound monomers to filament barbed ends via their interaction with profilin, but they were unable to elucidate the role of FH2 domains in polymerization. Wang and Vavylonis investigated the role of the fission yeast formin For3p in actin cable assembly (65) using experimental results published by Martin and Chang (66). Results from both studies suggest that For3p promotes actin cable formation by binding at the membrane in clusters. Clustering allows polymerizing filaments to be bundled because of their closely associated nucleation by For3p.

As the amount of experimental data on the roles of actin-binding proteins in actin network dynamics increases, experiment-driven modeling will become even more necessary to develop hypotheses that can be tested by further experimentation. Comprehensive modeling of regulatory proteins and dynamical actin processes will reveal the roles of specific proteins of interest in the context of the entire system. For instance, it will be useful to model formin-mediated actin networks in the context of cytoskeletal regulation by other known actin-binding proteins to understand how the cytoskeleton behaves in a cellular system in which formins are the primary mode of filament nucleation.

Assembly of the contractile ring in cytokinesis

A series of comprehensive studies demonstrate how models constructed with increasing complexity have revealed key mechanisms that regulate cytokinesis in fission yeast. These models relied on a quantitative catalog of the molecules and their interactions. Cytokinesis in fission yeast requires the formation and constriction of a contractile ring composed of actin, myosin, and actin-binding proteins. Experimental analysis has revealed the participating proteins (67), their concentrations (68), and the sequence of events leading up to cell division (69), making this an ideal process to model. Fission yeast initiates cytokinesis by creating nodes composed of motor proteins and actin-nucleating proteins. Actin filaments then populate the space between the nodes, and myosin II pulls the nodes together into a ring. Vavylonis and colleagues used a simple Monte Carlo simulation to test the mechanism by which nodes condensed to form a contractile ring (70). Initially, using only experimentally known parameters and mechanisms, their model predicted that nodes formed clusters rather than a contractile ring of actin filaments. Because their model did not accurately predict contractile ring formation, they included a search-and-capture mechanism to describe node motion. The revised, more complex model accurately predicted experimentally observed contractile ring formation. Following this investigation, the Pollard laboratory used a two-pronged investigation to examine the role of actin dendritic nucleation in the mechanism governing contractile ring formation (71,72). Using experimentally measured spatiotemporal data of actin patch formation (71), the investigators modeled contractile ring formation and determined that actin dendritic nucleation accounts for actin patch formation when a mechanism for filament severing is included in the model (72). The authors did not, however, test their model-predicted hypothesis for filament severing. Therefore, Chen and Pollard (73) examined the role of cofilin by building on the proposed search-and-capture mechanism. They predicted that cofilin was an essential component in ring formation, which they then confirmed via experiment. This progressive series of studies by the Pollard lab demonstrates the usefulness of systematically increasing model complexity to address questions that arise while studying a broader problem, in this case how actin dynamics control complex cellular processes.

Comprehensive models

In vitro experiments can yield valuable quantitative data on the individual interactions of actin with ABPs and regulatory proteins. Additional complexity can be accommodated with experiments on reconstituted systems with well-defined components, such as bead motility assays. However, in cells, the actin cytoskeleton can make use of a large repertoire of potential binders and regulators (Table S1). Furthermore, these molecules can be spatially localized within cells with highly intricate geometries, such as neurons or kidney podocytes. One way to address this complexity is through comprehensive models that, with appropriate customization, can be applied to multiple actin-driven mechanisms and used to answer multiple questions. Comprehensive models also offer an ideal means to organize the vast amounts of actin cytoskeletal data in a usable format.

The first comprehensive actin cytoskeletal model we highlight was created by Bindschadler and colleagues (74). Using published data (38,75–79), those authors constructed an ordinary-differential-equation model that explicitly accounted for nucleotide-dependent actin polymerization and depolymerization, capping, and regulation of G-actin activity by profilin and thymosin β4. Because this complex model included detailed regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, it was used to predict how varying the concentrations of G-actin-regulating proteins would affect actin polymerization in an experimentally testable manner. For example, because the model accounted for the ATP, ADP·Pi, and ADP forms of both G-actin and F-actin, the nucleotide profiles at steady state were determined for specific experimental conditions. The model predictions could then be experimentally tested in vitro. The model could also serve as a base model for testing the effect of ADF/cofilin severing and/or Arp2/3-mediated actin branching on actin polymerization, although these molecules were not explicitly considered.

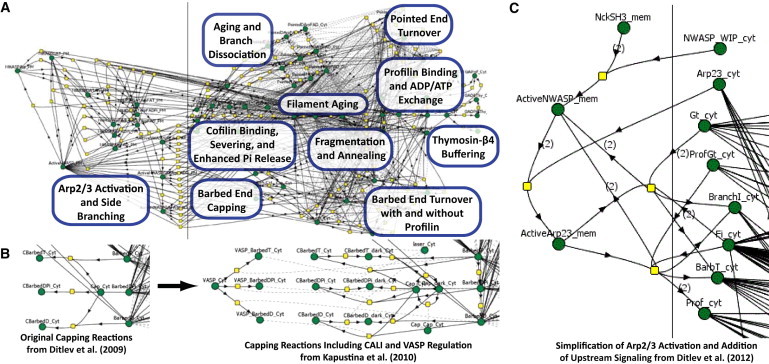

A comprehensive continuum model has been developed by our laboratory (80) and is openly available through the VCell database. It incorporates the processes described in the Bindschadler model while expanding it to include N-WASp activation of Arp2/3 at the membrane, Arp2/3-mediated actin branching (81, 82), cofilin regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (83, 84), and actin filament dynamics including fragmentation and annealing (85, 86) (Figure 2A). Among the important characteristics of this model that promote its use by the community of researchers studying the actin cytoskeleton are that 1), it exists in an accessible and extensible format, so it won’t need to be reconstructed from the ground up to test a new idea or to include additional molecular mechanisms; and 2), as demonstrated in Movie S1, it can be applied to any geometry, including the simulation of partial differential equations derived from imported three-dimensional microscope image data, allowing the effect of diffusion and spatial localization to be tested in realistic cellular geometries.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive VCell modeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Because of the open nature of models in the VCell, original models can be simplified and/or adapted at the user’s discretion to investigate previously unstudied aspects of actin regulation without building a new model. These models can then be used in a variety of geometries, i.e., lamellipodia or dendritic spines, or with a variety of experimentally simulatable systems, i.e., CALI or FRAP. (A) In the original Actin Dendritic Nucleation model (80), the actin cytoskeleton is regulated by the Arp2/3 complex, capping protein, cofilin, profilin, and thymosin-β4. (B) Building on the base model in (A), Kapustina and colleagues (89) added VASP regulation of capping protein and modeled the effects of CALI and FRAP on eGFP-capping protein-regulated actin dynamics. (C) Using an optimized version of the model, Ditlev and colleagues (90) created an upstream signaling module that activated Arp2/3 complex. With this reaction scheme, a previously unappreciated mechanism of the Nck/N-WASp/Arp2/3 complex pathway was elucidated.

Some components of this model illustrate the difficulties inherent in using deterministic modeling to describe cytoskeletal dynamics. To accurately formulate barbed- and pointed-end dynamics, the nucleotide state of both the end and the penultimate subunit must be known in order to correctly specify the stoichiometry of end dissociation. However, to reduce the combinatorial complexity of our continuum model, the nucleotide state (ATP, ADP·Pi, or ADP) of individual positions within filaments is not explicit. The model explicitly accounts for the nucleotide states at pointed and barbed ends, producing six variables; the rest of the F-actin in the interior of the filaments is lumped into three variables corresponding to the three nucleotide states. To approximate the correct stoichiometry and assure mass conservation in our model, the fractions of nucleotide states at the penultimate positions are taken to be equivalent to the fractions at the filament ends. As an example from this model, the rate of dissociation of an ADP-F-actin subunit from the pointed end to produce an ADP·Pi-F-actin pointed end and an ADP-G-actin monomer is given by

where kr is the rate constant for dissociation and S is an expression used to assure that the rate vanishes for filaments too short to contain an appropriate proportion of ADP·Pi subunits. This is one of several approximations that were required to capture the essential details of various mechanisms within the constraints of continuum modeling. However, this comprehensive model permitted us to simulate and explain such complex phenomena as the sharp transition from polymerization to depolymerization in the lamellipodium of a motile cell (87,88). Using a three-dimensional geometry of a cell with active N-WASp confined to the leading edge, we found that the dissociation of Arp2/3 branches just to the rear of the activation zone led to a large local steady-state concentration of depolymerizing pointed ends. Several other insights were derived from the model, but, importantly, it was able to serve as a base for two other studies investigating capping-protein regulation by VASP and a signaling mechanism governing local actin polymerization, as illustrated in Fig. 2, B and C, respectively.

Kapustina and colleagues adapted the model to investigate the effects of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) and chromophore-assisted laser inactivation (CALI) experiments on eGFP-capping protein (Fig. 2 B) (89). They found that to accurately predict the effects of FRAP or CALI on capping protein and the actin cytoskeleton, an uncapping mechanism must be included in the model, which they added in the form of VASP. Predictions from their model indicated that FRAP can be safely used with eGFP-capping protein, with no CALI-like effect, to investigate capping protein behavior in the lamellipodia. Furthermore, model simulations of the CALI-induced uncapping were consistent with experimental observations only if the uncapping activity of VASP was highly cooperative. Although there is indirect experimental evidence for such cooperativity, it is hoped that the modeling result will prompt further investigation of this important mechanism.

We have also used the Ditlev model (80) to investigate Nck-dependent actin polymerization (90) (Fig. 2 C). Experiments demonstrated a nonlinear relationship between Nck density on the membrane and actin polymerization; as Nck density in aggregates increased from 0% to 100%, actin polymerization increased nonlinearly from sparse actin spots to robust actin comet tails. Using an optimized version of the available model (Fig. 2 C), we found evidence for a previously unappreciated mechanism by which Nck activates N-WASp (90). Because we explicitly described the mechanism by which Nck activated N-WASp, we were able to test different mechanisms by which Nck activates Arp2/3 complex through N-WASp. The hypotheses suggested by the model, including a 4:2:1 stoichiometry for Nck/N-WASp/Arp2/3 and the involvement of WASP interacting protein in the signaling complex, were then experimentally tested and validated using quantitative fluorescent microscopy. Both the Kapustina et al. (89) and Ditlev et al. (90) studies benefited from detailed descriptions of actin biochemistry, allowing them to link signaling to the cytoskeleton while accounting for explicit perturbation of the cytoskeleton network.

In summary, comprehensive, detailed modeling of the actin cytoskeleton not only provides an opportunity to organize known experimental data in a useful manner, it provides a method to fully explore roles of interacting molecules that comprise this complex network. By explicitly including regulatory proteins and detailed kinetics, modelers are better equipped to treat remodeling of the cytoskeleton in response to various signaling inputs, providing researchers with a deeper understanding of how extracellular stimuli result in specific cellular responses. Additionally, the availability of open models, using either the VCell database or other model repositories, such as CellML (www.cellml.org) or BioModels (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/biomodels-main/), provides researchers with the opportunity to readily build on the work of others. An important caveat for any modeling study is that we can never be sure that the model is and its parameters are complete or accurate. It is our contention, however, that the process of iterative modeling and experiment is the most direct path toward a full understanding of complex biological systems. Indeed, it is in precisely those situations in which the model does not reproduce an experimental observable that the process of coupling model and experiment is most valuable, because this failure forces the investigator to carefully consider what is wrong with the hypotheses underlying the model.

Conceptual models that conform to Fermi’s four-parameter-elephant standard for elegance will always be of value in describing a global actin-dependent process such as cell migration, but we argue in this review that experiment-driven, comprehensive modeling is also vital as a tool for investigating the actin cytoskeleton and its regulation. From the earliest studies of actin polymerization, the actin cytoskeleton has lent itself to kinetic measurements and modeling. In vitro biochemistry has been the primary source for rate constants used in modeling the cytoskeleton. However, as technological advances push the field forward, methods to measure concentrations and rate constants in vivo will become ever more prevalent, thereby improving both the inputs to models and the experiments used to validate their predictions. Indeed, as more cytoskeletal regulators are identified and their functions elucidated, modeling will be essential for organizing the data and for developing hypotheses on the complex interplay of the myriad actin-binding and regulatory proteins.

Acknowledgments

We are pleased to acknowledge many stimulating discussions and contributions from Igor Novak, Paul Michalski, Maryna Kapustina, Ken Jacobson, Tom Pollard, and Alex Mogilner.

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health grants from the National Center for Research Resources (P41RR013186), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41GM103313), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (TR01DK087660), and the National Cancer Institute (RO1 CA82258).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Dyson F. A meeting with Enrico Fermi. Nature. 2004;427:297. doi: 10.1038/427297a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mogilner A., Oster G. Cell motility driven by actin polymerization. Biophys. J. 1996;71:3030–3045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79496-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peskin C.S., Odell G.M., Oster G.F. Cellular motions and thermal fluctuations: the Brownian ratchet. Biophys. J. 1993;65:316–324. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81035-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mogilner A., Allard J., Wollman R. Cell polarity: quantitative modeling as a tool in cell biology. Science. 2012;336:175–179. doi: 10.1126/science.1216380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer J., Khairy K., Howard J. Drawing an elephant with four complex parameters. Am. J. Phys. 2010;78:648–649. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard T.D. Regulation of actin filament assembly by Arp2/3 complex and formins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:451–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rafelski S.M., Theriot J.A. Crawling toward a unified model of cell mobility: spatial and temporal regulation of actin dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:209–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.dos Remedios C.G., Chhabra D., Nosworthy N.J. Actin binding proteins: regulation of cytoskeletal microfilaments. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:433–473. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominguez R., Holmes K.C. Actin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:169–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bugyi B., Carlier M.F. Control of actin filament treadmilling in cell motility. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:449–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051309-103849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S., Guan J.L., Chien S. Biochemistry and biomechanics of cell motility. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2005;7:105–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alves R., Antunes F., Salvador A. Tools for kinetic modeling of biochemical networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:667–672. doi: 10.1038/nbt0606-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaff J., Fink C.C., Loew L.M. A general computational framework for modeling cellular structure and function. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slepchenko B.M., Schaff J.C., Loew L.M. Quantitative cell biology with the Virtual Cell. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowan A.E., Moraru I.I., Loew L.M. Spatial modeling of cell signaling networks. Methods Cell Biol. 2012;110:195–221. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-388403-9.00008-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oosawa F., Kasai M. A theory of linear and helical aggregations of macromolecules. J. Mol. Biol. 1962;4:10–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(62)80112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oosawa F., Asakura S., Ooi T. G-F transformation of actin as a fibrous condensation. J. Polym. Sci. 1959;37:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wegner A. Head to tail polymerization of actin. J. Mol. Biol. 1976;108:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(76)80100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straub F.B., Feuer G. Adenosinetriphosphate. The functional group of actin. 1950. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;1000:180–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper J.A., Blum J.D., Pollard T.D. Acanthamoeba castellanii capping protein: properties, mechanism of action, immunologic cross-reactivity, and localization. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:217–225. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard T.D. Polymerization of ADP-actin. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:769–777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouyama T., Mihashi K. Fluorimetry study of N-(1-pyrenyl)iodoacetamide-labelled F-actin. Local structural change of actin protomer both on polymerization and on binding of heavy meromyosin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1981;114:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper J.A., Walker S.B., Pollard T.D. Pyrene actin: documentation of the validity of a sensitive assay for actin polymerization. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1983;4:253–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00712034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollard T.D., Cooper J.A. Actin and actin-binding proteins. A critical evaluation of mechanisms and functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986;55:987–1035. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vavylonis D., Yang Q., O’Shaughnessy B. Actin polymerization kinetics, cap structure, and fluctuations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8543–8548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501435102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiwara I., Vavylonis D., Pollard T.D. Polymerization kinetics of ADP- and ADP-Pi-actin determined by fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8827–8832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702510104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svitkina T.M., Borisy G.G. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1009–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchoin L., Amann K.J., Pollard T.D. Direct observation of dendritic actin filament networks nucleated by Arp2/3 complex and WASP/Scar proteins. Nature. 2000;404:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35010008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullins R.D., Heuser J.A., Pollard T.D. The interaction of Arp2/3 complex with actin: nucleation, high affinity pointed end capping, and formation of branching networks of filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlsson A.E. Growth velocities of branched actin networks. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2907–2918. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amann K.J., Pollard T.D. Direct real-time observation of actin filament branching mediated by Arp2/3 complex using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:15009–15013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211556398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volkmann N., Amann K.J., Hanein D. Structure of Arp2/3 complex in its activated state and in actin filament branch junctions. Science. 2001;293:2456–2459. doi: 10.1126/science.1063025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pantaloni D., Boujemaa R., Carlier M.F. The Arp2/3 complex branches filament barbed ends: functional antagonism with capping proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:385–391. doi: 10.1038/35017011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlsson A.E., Wear M.A., Cooper J.A. End versus side branching by Arp2/3 complex. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1074–1081. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraikivski P., Slepchenko B.M. Quantifying a pathway: kinetic analysis of actin dendritic nucleation. Biophys. J. 2010;99:708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaus T.E., Taylor E.W., Borisy G.G. Self-organization of actin filament orientation in the dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7086–7091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701943104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaus T.E., Borisy G.G. Performance of a population of independent filaments in lamellipodial protrusion. Biophys. J. 2008;95:1393–1411. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.125005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlier M.F., Jean C., Pantaloni D. Modulation of the interaction between G-actin and thymosin β4 by the ATP/ADP ratio: possible implication in the regulation of actin dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5034–5038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy P., Rajfur Z., Jacobson K. Local photorelease of caged thymosin β4 in locomoting keratocytes causes cell turning. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1035–1048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause M., Dent E.W., Gertler F.B. Ena/VASP proteins: regulators of the actin cytoskeleton and cell migration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.050103.103356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lacayo C.I., Pincus Z., Theriot J.A. Emergence of large-scale cell morphology and movement from local actin filament growth dynamics. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luxenburg C., Geblinger D., Addadi L. The architecture of the adhesive apparatus of cultured osteoclasts: from podosome formation to sealing zone assembly. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zettl M., Way M. New tricks for an old dog? Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:E74–E75. doi: 10.1038/35060152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryce N.S., Clark E.S., Weaver A.M. Cortactin promotes cell motility by enhancing lamellipodial persistence. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1276–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boguslavsky S., Grosheva I., Bershadsky A. p120 catenin regulates lamellipodial dynamics and cell adhesion in cooperation with cortactin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10882–10887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siton O., Ideses Y., Bernheim-Groswasser A. Cortactin releases the brakes in actin- based motility by enhancing WASP-VCA detachment from Arp2/3 branches. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:2092–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlier M.F., Laurent V., Pantaloni D. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pollard T.D., Borisy G.G. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghosh M., Song X., Condeelis J.S. Cofilin promotes actin polymerization and defines the direction of cell motility. Science. 2004;304:743–746. doi: 10.1126/science.1094561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlsson A.E. Stimulation of actin polymerization by filament severing. Biophys. J. 2006;90:413–422. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roland J., Berro J., Martiel J.L. Stochastic severing of actin filaments by actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin controls the emergence of a steady dynamical regime. Biophys. J. 2008;94:2082–2094. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huber F., Käs J., Stuhrmann B. Growing actin networks form lamellipodium and lamellum by self-assembly. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5508–5523. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chhabra E.S., Higgs H.N. The many faces of actin: matching assembly factors with cellular structures. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song X., Chen X., Eddy R.J. Initiation of cofilin activity in response to EGF is uncoupled from cofilin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in carcinoma cells. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2871–2881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moriyama K., Iida K., Yahara I. Phosphorylation of Ser-3 of cofilin regulates its essential function on actin. Genes Cells. 1996;1:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.05005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Rheenen J., Condeelis J., Glogauer M. A common cofilin activity cycle in invasive tumor cells and inflammatory cells. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:305–311. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tania N., Prosk E., Edelstein-Keshet L. A temporal model of cofilin regulation and the early peak of actin barbed ends in invasive tumor cells. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1883–1892. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kovar D.R., Kuhn J.R., Pollard T.D. The fission yeast cytokinesis formin Cdc12p is a barbed end actin filament capping protein gated by profilin. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:875–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kovar D.R., Pollard T.D. Insertional assembly of actin filament barbed ends in association with formins produces piconewton forces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14725–14730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harris E.S., Li F., Higgs H.N. The mouse formin, FRLalpha, slows actin filament barbed end elongation, competes with capping protein, accelerates polymerization from monomers, and severs filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20076–20087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moseley J.B., Sagot I., Goode B.L. A conserved mechanism for Bni1- and mDia1-induced actin assembly and dual regulation of Bni1 by Bud6 and profilin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:896–907. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pring M., Evangelista M., Zigmond S.H. Mechanism of formin-induced nucleation of actin filaments. Biochemistry. 2003;42:486–496. doi: 10.1021/bi026520j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pruyne D., Evangelista M., Boone C. Role of formins in actin assembly: nucleation and barbed-end association. Science. 2002;297:612–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1072309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vavylonis D., Kovar D.R., Pollard T.D. Model of formin-associated actin filament elongation. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang H., Vavylonis D. Model of For3p-mediated actin cable assembly in fission yeast. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin S.G., Chang F. Dynamics of the formin for3p in actin cable assembly. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guertin D.A., Trautmann S., McCollum D. Cytokinesis in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:155–178. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.155-178.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu J.Q., Pollard T.D. Counting cytokinesis proteins globally and locally in fission yeast. Science. 2005;310:310–314. doi: 10.1126/science.1113230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu J.Q., Kuhn J.R., Pollard T.D. Spatial and temporal pathway for assembly and constriction of the contractile ring in fission yeast cytokinesis. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:723–734. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vavylonis D., Wu J.Q., Pollard T.D. Assembly mechanism of the contractile ring for cytokinesis by fission yeast. Science. 2008;319:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1151086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sirotkin V., Berro J., Pollard T.D. Quantitative analysis of the mechanism of endocytic actin patch assembly and disassembly in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:2894–2904. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berro J., Sirotkin V., Pollard T.D. Mathematical modeling of endocytic actin patch kinetics in fission yeast: disassembly requires release of actin filament fragments. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:2905–2915. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Q., Pollard T.D. Actin filament severing by cofilin is more important for assembly than constriction of the cytokinetic contractile ring. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:485–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bindschadler M., Osborn E.A., McGrath J.L. A mechanistic model of the actin cycle. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2720–2739. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74326-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pollard T.D. Rate constants for the reactions of ATP- and ADP-actin with the ends of actin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 1986;103:2747–2754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blanchoin L., Pollard T.D. Hydrolysis of ATP by polymerized actin depends on the bound divalent cation but not profilin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:597–602. doi: 10.1021/bi011214b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Selden L.A., Kinosian H.J., Gershman L.C. Impact of profilin on actin-bound nucleotide exchange and actin polymerization dynamics. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2769–2778. doi: 10.1021/bi981543c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Melki R., Fievez S., Carlier M.F. Continuous monitoring of Pi release following nucleotide hydrolysis in actin or tubulin assembly using 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside and purine-nucleoside phosphorylase as an enzyme-linked assay. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12038–12045. doi: 10.1021/bi961325o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kang F., Purich D.L., Southwick F.S. Profilin promotes barbed-end actin filament assembly without lowering the critical concentration. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:36963–36972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ditlev J.A., Vacanti N.M., Loew L.M. An open model of actin dendritic nucleation. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3529–3542. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mahaffy R.E., Pollard T.D. Kinetics of the formation and dissociation of actin filament branches mediated by Arp2/3 complex. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3519–3528. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beltzner C.C., Pollard T.D. Pathway of actin filament branch formation by Arp2/3 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:7135–7144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blanchoin L., Pollard T.D. Mechanism of interaction of Acanthamoeba actophorin (ADF/Cofilin) with actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15538–15546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cao W., Goodarzi J.P., De La Cruz E.M. Energetics and kinetics of cooperative cofilin-actin filament interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andrianantoandro E., Blanchoin L., Pollard T.D. Kinetic mechanism of end-to-end annealing of actin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:721–730. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sept D., Xu J., McCammon J.A. Annealing accounts for the length of actin filaments formed by spontaneous polymerization. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2911–2919. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ponti A., Matov A., Danuser G. Periodic patterns of actin turnover in lamellipodia and lamellae of migrating epithelial cells analyzed by quantitative Fluorescent Speckle Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2005;89:3456–3469. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ponti A., Machacek M., Danuser G. Two distinct actin networks drive the protrusion of migrating cells. Science. 2004;305:1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1100533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kapustina M., Vitriol E., Jacobson K. Modeling capping protein FRAP and CALI experiments reveals in vivo regulation of actin dynamics. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:519–534. doi: 10.1002/cm.20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ditlev J.A., Michalski P.J., Mayer B.J. Stoichiometry of Nck-dependent actin polymerization in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:643–658. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jockusch B.M., Isenberg G. Interaction of alpha-actinin and vinculin with actin: opposite effects on filament network formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:3005–3009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van Etten R.A., Jackson P.K., Baltimore D., Sanders M.C., Matsuidaira P.T., Janmey P.A. The COOH terminus of the c-Abl tyrosine kinase contains distinct F- and G-actin binding domains with bundling activity. J. Cell Biol. 1994;124:325–340. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barrientos T., Frank D., Kuwahara K., Bezprozvannaya S., Pipes G.C., Bassel-Duby R., Richardson J.A., Katus H.A., Olson E.N., Frey N. Two novel members of the ABLIM protein family, ABLIM-2 and -3, associate with STARS and directly bind F-actin. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8393–8403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goode B.L., Rodal A.A., Barnes G., Drubin D.G. Activation of the Arp2/3 complex by the actin filament binding protein Abp1p. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:627–634. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zalevsky J., Grigorova I., Mullins R.D. Activation of the Arp2/3 complex by the Listeria acta protein. Acta binds two actin monomers and three subunits of the Arp2/3 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3468–3475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cicchetti G., Maurer P., Wagener P., Kocks C. Actin and phosphoinositide binding by the ActA protein of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33616–33626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ohtaki T., Tsukita S., Mimura N., Asano A. Interaction of actinogelin with actin. No nucleation but high gelation activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985;153:609–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bubb M.R., Knutson J.R., Porter D.K., Korn E.D. Actobindin induces the accumulation of actin dimers that neither nucleate polymerization nor self-associate. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:25592–25597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lambooy P.K., Korn E.D. Purification and characterization of actobindin, a new actin monomer-binding protein from Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:17150–17155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nikolopoulos S.N., Turner C.E. Actopaxin, a new focal adhesion protein that binds paxillin LD motifs and actin and regulates cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1435–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mische S.M., Mooseker M.S., Morrow J.S. Erythrocyte adducin: a calmodulin-regulated actin-bundling protein that stimulates spectrin-actin binding. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2837–2845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ressad F., Didry D., Xia G.X., Hong Y., Chua N.H., Pantaloni D., Carlier M.F. Kinetic analysis of the interaction of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin with G- and F-actins. Comparison of plant and human ADFs and effect of phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20894–20902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qian Y., Baisden J.M., Cherezova L., Summy J.M., Guappone-Koay A., Shi X., Mast T., Pustula J., Zot H.G., Mazloum N., Lee M.Y., Flynn D.C. PKC phosphorylation increases the ability of AFAP-110 to cross-link actin filaments. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2311–2322. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E01-12-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Iida K., Yahara I. Cooperation of two actin-binding proteins, cofilin and Aip1, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells. 1999;4:21–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clarke F.M., Morton D.J. Aldolase binding to actin-containing filaments. Formation of paracrystals. Biochem. J. 1976;159:797–798. doi: 10.1042/bj1590797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.O'Reilly G., Clarke F. Identification of an actin binding region in aldolase. FEBS Lett. 1993;321:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80623-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Patel D.M., Ahmad S.F., Weiss D.G., Gerke V., Kuznetsov S.A. Annexin A1 is a new functional linker between actin filaments and phagosomes during phagocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:578–588. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Goebeler V., Ruhe D., Gerke V., Rescher U. Annexin A8 displays unique phospholipid and F-actin binding properties. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2430–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Merrifield C.J., Rescher U., Almers W., Proust J., Sechi A.S., Moss S.E. Annexin 2 has an essential role in actin-based macropinocytic rocketing. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1136–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tzima E., Trotter P.J., Orchard M.A., Walker J.H. Annexin V binds to the actin-based cytoskeleton at the plasma membrane of activated platelets. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;251:185–193. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tzima E., Trotter P.J., Orchard M.A., Walker J.H. Annexin V relocates to the platelet cytoskeleton upon activation and binds to a specific isoform of actin. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4720–4730. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oh S.W., Pope R.K., Smith K.P., Crowley J.L., Nebl T., Lawrence J.B., Luna E.J. Archvillin, a muscle-specific isoform of supervillin, is an early expressed component of the costameric membrane skeleton. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2261–2275. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.MacGrath S.M., Koleske A.J. Arg/Abl2 modulates the affinity and stoichiometry of cortactin binding to F-actin. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6644–6653. doi: 10.1021/bi300722t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang Y., Miller A.L., Mooseker M.S., Koleske A.J. The Abl-related gene (Arg) nonreceptor tyrosine kinase uses two F-actin-binding domains to bundle F-actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14865–14870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251249298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reddy S.R., Houmeida A., Benyamin Y., Roustan C. Interaction in vitro of scallop muscle arginine kinase with filamentous actin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;206:251–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Amann K.J., Pollard T.D. The Arp2/3 complex nucleates actin filament branches from the sides of pre-existing filaments. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:306–310. doi: 10.1038/35060104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sanabria H., Swulius M.T., Kolodziej S.J., Liu J., Waxham M.N. {beta}CaMKII regulates actin assembly and structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:9770–9780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809518200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shuster C.B., Lin A.Y., Nayak R., Herman I.M. Beta cap73: a novel beta actin-specific binding protein. Cell. Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1996;35:175–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)35:3<175::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ferjani I., Fattoum A., Maciver S.K., Manai M., Benyamin Y., Roustan C. Calponin binds G-actin and F-actin with similar affinity. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4801–4806. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mornet D., Harricane M.C., Audemard E. A 35-kilodalton fragment from gizzard smooth muscle caldesmon that induces F-actin bundles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;155:808–815. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sobue K., Takahashi K., Tanaka T., Kanda K., Ashino N., Kakiuchi S., Maruyama K. Crosslinking of actin filaments is caused by caldesmon aggregates, but not by its dimers. FEBS Lett. 1985;182:201–204. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chaudhry, Little K., Talarico L., Quintero-Monzon O., Goode B.L. A central role for the WH2 domain of Srv2/CAP in recharging actin monomers to drive actin turnover in vitro and in vivo. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:120–133. doi: 10.1002/cm.20429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Heiss S.G., Cooper J.A. Regulation of CapZ, an actin capping protein of chicken muscle, by anionic phospholipids. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8753–8758. doi: 10.1021/bi00100a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hug C., Miller T.M., Torres M.A., Casella J.F., Cooper J.A. Identification and characterization of an actin-binding site of CapZ. J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:923–931. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Llorca O., McCormack E.A., Hynes G., Grantham J., Cordell J., Carrascosa J.L., Willison K.R., Fernandez J.J., Valpuesta J.M. Eukaryotic type II chaperonin CCT interacts with actin through specific subunits. Nature. 1999;402:693–696. doi: 10.1038/45294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thacker E., Kearns B., Chapman C., Hammond J., Howell A., Theibert A. The arf6 GAP centaurin alpha-1 is a neuronal actin-binding protein which also functions via GAP-independent activity to regulate the actin cytoskeleton. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2004;83:541–554. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Provost P., Doucet J., Stock A., Gerish G., Samuelsson B., Radmark O. Coactosin-like protein, a human F-actin-binding protein: critical role of lysine-75. Biochem. J. 2001;359:255–263. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.de Hostos E.L., Bradtke B., Lottspeich F., Gerish G. Coactosin, a 17 kDa F-actin binding protein from Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1993;26:181–191. doi: 10.1002/cm.970260302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weiner O.H., Murphy J., Griffiths G., Schleicher M., Noegel A.A. The actin-binding protein comitin (p24) is a component of the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 1993;123:23–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pant K., Chereau D., Hatch V., Dominguez R., Lehman W. Cortactin binding to F-actin revealed by electron microscopy and 3D reconstruction. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Goode B.L., Wong J.J., Butty A.C., Peter M., McCormack A.L., Yates J.R., Drubin D.G., Barnes G. Coronin promotes the rapid assembly and cross-linking of actin filaments and may link the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:83–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tardieux I., Liu X., Poupel O., Parzy D., Dehoux P., Langsley G. A Plasmodium falciparum novel gene encoding a coronin-like protein which associates with actin filaments. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Higashi T., Ikeda T., Murakami T., Shirakawa R., Kawato M., Okawa K., Furuse M., Kimura T., Kita T., Horiuchi H. Flightless-I (Fli-I) regulates the actin assembly activity of diaphanous-related formins (DRFs) Daam1 and mDia1 in cooperation with active Rho GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:16231–16238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Li F., Higgs H.N. The mouse Formin mDia1 is a potent actin nucleation factor regulated by autoinhibition. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1335–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00540-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pellegrin S., Mellor H. The Rho family GTPase Rif induces filopodia through mDia2. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Morrison S.S., Dawson J.F. A high-throughput assay shows that DNase-I binds actin monomers and polymers with similar affinity. Anal. Biochem. 2007;364:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Shirao T., Hayashi K., Ishikawa R., Isa K., Asada H., Ikeda K., Uyemura K. Formation of thick, curving bundles of actin by drebrin A expressed in fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 1994;215:145–153. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ohlendieck K. Towards an understanding of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: linkage between the extracellular matrix and the membrane cytoskeleton in muscle fibers. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 1996;69:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Koenig M., Monaco A.P., Kunkel L.M. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell. 1988;53:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Murray J.W., Edmonds B.T., Liu G., Condeelis J. Bundling of actin filaments by elongation factor 1 alpha inhibits polymerization at filament ends. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:1309–1321. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Leinweber B.D., Leavis P.C., Grabarek Z., Wang C.L., Morgan K.G. Extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) interaction with actin and the calponin homology (CH) domain of actin-binding proteins. Biochem. J. 1999;344:117–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kahsai A.W., Zhu S., Wardrop D.J., Lane W.S., Fenteany G. Quinocarmycin analog DX-52-1 inhibits cell migration and targets radixin, disrupting interactions of radixin with actin and CD44. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:973–983. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yao X., Cheng L., Forte J.G. Biochemical characterization of ezrin-actin interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7224–7229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tao Y.S., Edwards R.A., Tubb B., Wang S., Bryan J., McCrea P.D. beta-Catenin associates with the actin-bundling protein fascin in a noncadherin complex. J. Cell Biol. 1996;134:1271–1281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Leinweber B.D., Fredricksen R.S., Hoffman D.R., Chalovich J.M. Fesselin: a novel synaptopodin-like actin binding protein from muscle tissue. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1999;20:539–545. doi: 10.1023/a:1005597306671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Takeya R., Sumimoto H. Fhos, a mammalian formin, directly binds to F-actin via a region N-terminal to the FH1 domain and forms a homotypic complex via the FH2 domain to promote actin fiber formation. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:4567–4575. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Shizuta Y., Shizuta H., Gallo M., Davies P., Pastan I. Purification and properties of filamin, and actin binding protein from chicken gizzard. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:6562–6567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zigmond S.H. Formin-induced nucleation of actin filaments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Furuhashi K., Hatano S. Control of actin filament length by phosphorylation of fragmin-actin complex. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:1081–1087. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Leu B., Koch E., Schmidt J.T. GAP43 phosphorylation is critical for growth and branching of retinotectal arbors in zebrafish. Dev. Neurobiol. 2010;70:897–911. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Vargas M., Sansonetti P., Guillen N. Identification and cellular localization of the actin-binding protein ABP-120 from Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;22:849–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Harris H.E., Weeds A.G. Plasma gelsolin caps and severs actin filaments. FEBS Lett. 1984;177:184–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Schoepper B., Wegner A. Rate constants and equilibrium constants for binding of actin to the 1:1 gelsolin-actin complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;202:1127–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Baque S., Guinovart J.J., Ferrer J.C. Glycogenin, the primer of glycogen synthesis, binds to actin. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Zhang S., Buder K., Burkhardt C., Schlott B., Gorlach M., Grosse F. Nuclear DNA helicase II/RNA helicase A binds to filamentous actin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:843–853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Engqvist-Goldstein A.E., Warren R.A., Kessels M.M., Keen J.H., Heuser J., Drubin D.G. The actin-binding protein Hip1R associates with clathrin during early stages of endocytosis and promotes clathrin assembly in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:1209–1223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Benedetti C.E., Kobarg J., Pertinhez T.A., Gatti R.M., de Souza O.N., Spisni A., Meneghini R. Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein II binds to actin, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and erythrocyte ghosts in a pH-dependent manner and undergoes coil-to-helix transitions in anionic micelles. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003;128:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Percipalle P., Zhao J., Pope B., Weeds A., Lindberg U., Daneholt B. Actin bound to the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein hrp36 is associated with Balbiani ring mRNA from the gene to polysomes. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:229–236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Nishida E., Koyasu S., Sakai H., Yahara I. Calmodulin-regulated binding of the 90-kDa heat shock protein to actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:16033–16036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Ruhnau K., Gaertner A., Wegner A. Kinetic evidence for insertion of actin monomers between the barbed ends of actin filaments and barbed end-bound insertin, a protein purified from smooth muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;210:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Zuchero J.B., Belin B., Mullins R.D. Actin binding to WH2 domains regulates nuclear import of the multifunctional actin regulator JMY. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:853–863. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-0992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Bearer E.L., Abraham M.T. 2E4 (kaptin): a novel actin-associated protein from human blood platelets found in lamellipodia and the tips of the stereocilia of the inner ear. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1999;78:117–126. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.van Straaten M., Goulding D., Kolmerer B., Labeit S., Clayton J., Leonard K., Bullard B. Association of kettin with actin in the Z-disc of insect flight muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1549–1562. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Lepley R.A., Fitzpatrick F.A. 5-Lipoxygenase contains a functional Src homology 3-binding motif that interacts with the Src homology 3 domain of Grb2 and cytoskeletal proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:24163–24168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kim A.C., Peters L.L., Knoll J.H., Van Huffel C., Ciciotte S.L., Kleyn P.W., Chishti A.H. Limatin (LIMAB1), an actin-binding LIM protein, maps to mouse chromosome 19 and human chromosome 10q25, a region frequently deleted in human cancers. Genomics. 1997;46:291–293. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Jongstra-Bilen J., Janmey P.A., Hartwig J.H., Galea S., Jongstra J. The lymphocyte-specific protein LSP1 binds to F-actin and to the cytoskeleton through its COOH-terminal basic domain. J. Cell Biol. 1992;118:1443–1453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.6.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Hartwig J.H., Thelen M., Rosen A., Janmey P.A., Nairn A.C., Aderem A. MARCKS is an actin filament crosslinking protein regulated by protein kinase C and calcium-calmodulin. Nature. 1992;356:618–622. doi: 10.1038/356618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Jiang S., Avraham H.K., Park S.Y., Kim T.A., Bu X., Seng S., Avraham S. Process elongation of oligodendrocytes is promoted by the Kelch-related actin-binding protein Mayven. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:1191–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.James M.F., Manchanda N., Gonzalez-Agosti C., Hartwig J.H., Ramesh V. The neurofibromatosis 2 protein product merlin selectively binds F-actin but not G-actin, and stabilizes the filaments through a lateral association. Biochem. J. 2001;356:377–386. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Mattila P.K., Salminen M., Yamashiro T., Lappalainen P. Mouse MIM, a tissue-specific regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, interacts with ATP-actin monomers through its C-terminal WH2 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:8452–8459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Boggs J.M., Rangaraj G. Interaction of lipid-bound myelin basic protein with actin filaments and calmodulin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7799–7806. doi: 10.1021/bi0002129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Weins A., Schwarz K., Faul C., Barisoni L., Linke W.A., Mundel P. Differentiation- and stress-dependent nuclear cytoplasmic redistribution of myopodin, a novel actin-bundling protein. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:393–404. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200012039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Sellers J.R., Pato M.D. The binding of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase and phosphatases to actin and myosin. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:7740–7746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Chantler P.D., Gratzer W.B. The interaction of actin monomers with myosin heads and other muscle proteins. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2219–2225. doi: 10.1021/bi00655a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Shibata-Sekiya K., Tonomura Y. Structure and function of the two heads of the myosin molecule. III. Cooperativity of the two heads of the myosin molecule, shown by the effect of modification of head A with rho-chloromercuribenzoate on the interaction of head B with F-actin. J. Biochem. 1976;80:1371–1380. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Jin J.P., Wang K. Nebulin as a giant actin-binding template protein in skeletal muscle sarcomere. Interaction of actin and cloned human nebulin fragments. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80366-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Burnett P.E., Blackshaw S., Lai M.M., Qureshi I.A., Burnett A.F., Sabatini D.M., Snyder S.H. Neurabin is a synaptic protein linking p70 S6 kinase and the neuronal cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8351–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Luo G., Herrera A.H., Horowits R. Molecular interactions of N-RAP, a nebulin-related protein of striated muscle myotendon junctions and intercalated disks. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6135–6143. doi: 10.1021/bi982395t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Co C., Wong D.T., Gierke S., Chang V., Taunton J. Mechanism of actin network attachment to moving membranes: barbed end capture by N-WASP WH2 domains. Cell. 2007;128:901–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Egile C., Loisel T.P., Laurent V., Li R., Pantaloni D., Sansonetti P.J., Carlier M.F. Activation of the CDC42 effector N-WASP by the Shigella flexneri IcsA protein promotes actin nucleation by Arp2/3 complex and bacterial actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:1319–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Metcalfe S., Weeds A., Okorokov A.L., Milner J., Cockman M., Pope B. Wild-type p53 protein shows calcium-dependent binding to F-actin. Oncogene. 1999;18:2351–2355. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]