Abstract

A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer is currently ongoing in Korea. Patients with cT1N0M0-cT2aN0M0 (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 6th edition) distal gastric cancer were randomized to receive either laparoscopic or open distal gastrectomy. For surgical quality control, the surgeons participating in this trial had to have performed at least 50 cases each of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy and open distal gastrectomy and their institutions should have performed more than 80 cases each of both procedures each year. Fifteen surgeons from 12 institutions recruited 1,415 patients. The primary endpoint is overall survival. The secondary endpoints are disease-free survival, morbidity, mortality, quality of life, inflammatory and immune responses, and cost-effectiveness (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT00452751).

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Laparoscopy distal gastrectomy, Open distal gastrectomy, Randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Since Kitano et al. [1] reported the first case of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) in 1994, it has been used widely to treat gastric cancer due to the known benefits of the minimally invasive approach, such as decreased pain, length of hospital stay, blood loss, and complications [2-6]. However, many controversies still exist due to no prospective large scale clinical trials to evaluate the long term outcomes. Therefore, the Korean Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group reviewed the multicenter data of ten institutions retrospectively and analyzed them to evaluate the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic gastrectomy, before launching a prospective study [7-12]. On the basis of these retrospective result which was comparable to that of open gastrectomy, phase III surgical trial to verify the long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy was initiated by KLASS group. The Clinical Trial Review Committee of the KLASS Group approved the protocol on July, 2005 and the study was activated on February, 2006. This study is the first prospective, randomized, multicenter trial that compares LADG with open distal gastrectomy (ODG) in Korea.

METHODS

Study objectives

The primary objective of this study is to assess whether the laparoscopic surgery is comparable to open gastrectomy in terms of long-term outcomes without compromising overall survival. The secondary research objectives are to compare LADG and ODG in terms of disease free survival, morbidity, mortality, quality of life, inflammatory and immune responses, and cost-effectiveness.

Study setting

The study has received Ethical Committee approval. The KLASS 01 trial is a controlled randomized multicenter trial that is examining the usefulness of laparoscopic surgery in 1,415 patients with gastric cancer who have been recruited in 12 tertiary hospitals in Korea.

Study population

The patient inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) pathologically proven gastric adenocarcinoma, 2) age of 20 to 80 years, 3) a preoperative stage of cT1N0M0, cT1N1M0, and cT2aN0M0 according to American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control 6th edition, 4) no history of other cancers, and 5) no history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The patient exclusion criteria were the following: 1) American Society of Anesthesiologists class > 3, 2) need for combined resection, and 3) total gastrectomy. All patients freely gave informed consent to participate in the study and can decide to withdraw from the study at any time.

Treatment methods

For surgical quality control, surgeons could only participate in this trial if they had performed at least 50 cases each of LADG and ODG and more than 80 cases of either method were performed in their institution each year. All participating surgeons reviewed thoroughly unedited video each other performing LADG and established standardized protocol of the procedure.

The extent of lymphadenectomy was determined on the basis of the second version of the Japanese Guideline of Gastric Cancer [13]. A standard radical distal gastrectomy with more than D1 + β lymph node dissection was performed in both the LADG and ODG groups. Dissection of the No. 14v lymph nodes was optional. Omentectomy was performed partially and reconstruction was performed by the standard Billroth I/II or Roux-en-Y fashion, depending on the preference of the surgeon. To evaluate the adequacy of all surgeries that were performed during the entire study period, LADGs were recorded and standardized operative field photos of ODGs were taken and reviewed.

Randomization, allocation and data collection

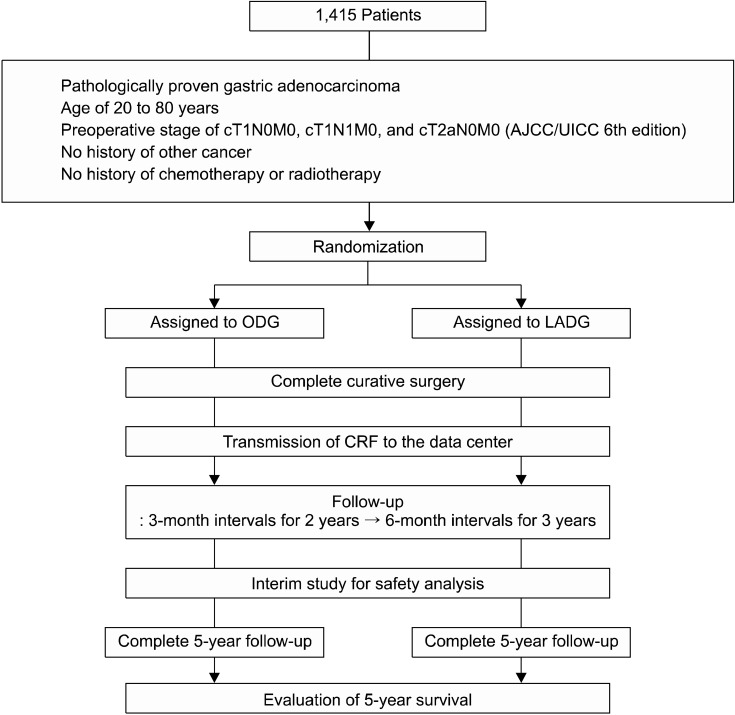

After confirming the patients met the inclusion/exclusion criteria by telephoning the data center, the patients were registered into the trial and then randomized to one of two groups (LADG or ODG) on the basis of a computer-generated randomization list. Randomization was coordinated centrally by the independent data center and aimed to balance the arms according to each institution. Randomization was performed in order of the day of initial evaluation. The data center then received the first case report form (CRF) about the preoperative staging, operative findings, pathological report, and postoperative outcomes from each institute and placed the data into the local database via data registry server (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scheme diagram of the stydy. AJCC/UICC, American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control; ODG, open distal gastrectomy; LADG, laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy; CRF, case report form.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoint

Five-year overall survival will be evaluated in 2015. If a subject dies, the date of death, the cause of death, and how the death was identified are entered on the CRF. If patients are lost after the last follow-up, survival data are collected by communicating with the patients or their family via telephone or letter.

Secondary end points

Disease-free survival and recurrence

This will be assessed by regular follow-up. The site and the time a recurrence is diagnosed is recorded. The date of recurrence, pattern of recurrence, and how the recurrence was identified are entered on the CRF in as much detail as possible. The recurrence pattern is classified into eight categories: remnant gastric, locoregional, peritoneal, hepatic and extrahepatic hematogenous, lymphatic, mixed, and other recurrences. Remnant gastric recurrence includes tumors in the anastomosis or gastric stump. Locoregional recurrence includes tumors in adjacent organs, including the gastric bed, porta hepatis, abdominal wall and the regional lymph nodes (perigastric, left gastric, common hepatic, celiac, and hepatoduodenal). Peritoneal recurrence is defined as peritoneal seeding or Krukenberg's tumor. Hematogenous metastasis is divided into hepatic and extrahepatic hematogenous recurrence. The latter includes recurrence in the lung, bone, brain, or other distant sites. Lymphatic recurrence is defined as tumors in the paraaortic, inguinal, Virchow's or other distant lymph nodes, or lung lymphangitic metastasis. The mixed pattern of recurrence includes those recurrences where the criteria for two or more of the above categories are met simultaneously. Other recurrences include suspected recurrence such as tumor marker elevation.

Morbidity and mortality

Early postoperative morbidity is defined as complications that occur within thirty days after surgery. Early postoperative morbidity is classified as follows: 1) wound morbidity: operation wound with seroma, hematoma, infection, dehiscence, or evisceration, etc.; 2) surgical site morbidity: anastomosis bleeding or leakage, duodenal stump leakage, postoperative bleeding, afferent loop or efferent loop obstruction, etc.; 3) lung morbidity: atelectasis, pleural effusion, empyema, pneumothorax, etc.; 4) intestinal obstruction morbidity: no return of bowel movement until 5 days after surgery, mechanical obstruction with an air-fluid level or paralytic ileus on simple X-ray, etc.; 5) urinary tract morbidity: frequency, nocturia, dysuria, increased white blood cell count on urine analysis, etc.; 6) intra-abdominal abscess: the presence of septic fluid in the abdominal cavity that causes fever higher than 38℃ and is proven by abdominal sonography or computed tomography (CT) scanning; 7) postoperative pancreatitis: elevated serum amylase (>150 U/L) with symptoms that are suggestive of pancreatitis such as back pain and fever; 8) pancreatic fistula: drain amylase content greater than 1,000 U/L after postoperative day 3; 9) intestinal fistula: presence of a bowel to bowel or bowel to cutaneous fistula tract that is confirmed by a fistulogram; 10) others: lymphorrhea, diarrhea, etc.

Late postoperative morbidity is defined as complications that occur after postoperative day 30. Late postoperative morbidity is classified as follows: 1) adhesive ileus: mechanical or paralytic obstruction on CT scan accompanied by symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and no gas passing; 2) anastomosis stricture: narrowing of the anastomosis that is confirmed by upper gastrointestinal series; 3) reflux esophagitis: esophageal erosion to the stricture that is confirmed by endoscopy; 4) malnutrition: iron deficiency anemia, megaloblastic anemia, or steatorrhea; 5) dumping syndrome.

Operative mortality refers to all hospital deaths

Quality of life (QoL)

This is assessed by the Korean versions of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (ver. 3.0) and STO22 questionnaires and the KLASS questionnaire, which was formulated by our group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 consists of a 30-item cancer-specific integrated system for assessing key functional aspects of health-related (QoL), the global QoL, and symptoms that commonly occur in cancer patients. It incorporates five function scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea and vomiting), a global health and QoL scale, and single items for assessing additional symptoms that are commonly reported by cancer patients (e.g. dyspnea, appetite loss, sleep disturbance, constipation, and diarrhea), and the perceived financial impact of the disease and treatment. Of the 30 items, 28 items are scored on a four-point Likert scale and the remaining two items for the global health status scale are scored on modified seven-point linear analog scales. All scales were linearly transformed to a 0 to 100 score, with 100 representing the best global health status or functional status or the worst symptom status. The EORTC QLQ-STO22, a stomach cancer-specific questionnaire, consists of 22 items. It includes five scales (dysphasia, eating restrictions, pain, reflux, and anxiety) and four single items (dry mouth, body image, taste problems, and hair loss) that reflect disease symptoms, treatment side effects, and emotional issues that are specific to gastric cancer, with high scores indicating worse symptomatic problems [14].

The KLASS questionnaire was composed of five scales (subjective well-being, treatment satisfaction, health perception, wound, and scar scales). The items of each scale reflect the advantages that are associated with laparoscopic surgery. The subjective well-being scale, the treatment satisfaction scale, and the health perception scale were formulated by transforming the contents of the questionnaires used in research by Hahn and Park [15]. Subjective well-being and treatment satisfaction are each evaluated with three items. The health perception scale is composed of six items. The wound scale and the scar scale are composed of 14 items. Of these 14 items, eight items relate to wound pain (presence of pain, degree of symptoms, pattern of symptoms, and degree of discomfort due to wound pain in daily life), five items relate to the scar (changes in mood due to the scar, impact on personal activity, impact on daily activity, impact on leisure activity, and satisfaction), and one item is about whether the patients would recommend the operative method they received to others. The items about the sequelae of the abdominal incision were initially formulated by the researchers of the KLASS group and then reviewed by a clinical psychologist. This questionnaire was applied to 206 of the patients who were enrolled in the KLASS trial between February, 2006 and February, 2007. It turned out to be so feasible that the KLASS group has continued to use it till now. Postoperative QoL data are collected by directly contacting patients at baseline (before surgery) and on every follow-up visit after surgery (at 2 weeks, 3, 6, and 12 months, and 3 and 5 years).

Inflammatory and immune responses

This study will be conducted in 100 patients (50 who receive LADG and 50 who receive ODG). C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6 will be measured to assess the inflammatory reaction induced by each operation. Total lymphocyte, T-cell subset, B cell and natural killer cell counts, and IL-2 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels will be measured to compare the immune response before surgery and at 2 hours, 1st, 4th, 30th day after surgery. Patient serum will be prepared by centrifuging clotted blood for ten minutes at 3,000 rpm. The serum will then be stored in aliquots at -80℃. After collecting all specimens required for experimentation, TNF and the ILs will be measured quantitatively by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method and CRP will be measured quantitatively by the immunoturbidimetric assay. At the last follow-up, the impact of inflammatory or immune response on 5-year overall survival will be evaluated.

Cost-effectiveness

At discharge, the total cost will be calculated and the two groups will be compared with regard to cost-effectiveness. We evaluated not only social cost which may be calculated by time needed to resume normal social activity but also "willingness to pay" reflecting individual patient preference for a particular procedure. Information regarding factors affect cost (length of hospital stay, complications, presence of comorbidity, etc.) will be collected.

Follow-up

The patients in both groups will be followed up at 3-month intervals for 2 years, and then at 6-month intervals for 3 years. At every follow-up, a physical examination, a complete blood count, nutritional indicators (total protein, albumin, and transferrin), liver-function testing, and tumor marker (careinoembryonal antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9) analyses will be performed. Endoscopy, abdomen sonography and CT scanning will be performed twice a year until 2 years after surgery and yearly thereafter. The site and date of the first relapse and the date of death, if the patient died, will be recorded.

Statistical methods

This trial is designed to compare laparoscopic distal gastrectomy to the standard conventional open distal gastrectomy in terms of overall survival. The hypothesis to be tested is that the 5-year survival rate after the laparoscopic approach is 5% less than the 5-year survival rate after ODG, which is estimated to be 90%. Allowing for a dropout rate of 10%, the planned sample size was 1,400, with 700 cases per arm, with 5 years of follow-up after 5 years of accrual. This will provide a power of 80% to reject the null hypothesis with a significance level at less than 0.05.

Study monitoring and interim analysis

A Trial Steering Committee meets every 6 months and will be responsible for drafting the final report and submission for publication. The monitoring reports are submitted to and reviewed by the data and safety monitoring committee every 6 months. Soon after recruitment had started, a data and safety monitoring committee met at the start of the trial to establish a charter, and will continue to meet at least annually to determine if there are any ethical problems.

To evaluate the safety of this trial, one interim analysis was planned. The interim analysis tested the hypothesis that the LADG- and ODG-associated morbidity in this trial did not differ significantly from the morbidity reported in previous studies on open gastric cancer surgeries. This analysis showed that the two groups did not differ significantly in terms of morbidity or mortality [16]. Therefore, it was concluded that this trial was safe and the study was continued.

Progress

Enrollment ended on August, 2010. In total, 1,415 patients from 12 surgical departments have participated in this study. Of these, 704 underwent LADG and 711 underwent ODG. The results are expected to be reported in September, 2015.

Participating institutions (A to Z)

Ajou University Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea St. Mary's Hospital, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Hospital, Dong-A University Hospital, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Keimyung University Hospital, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Yonsei University Hospital.

DISCUSSION

During the last 2 decades, the proportion of early gastric cancers (EGCs) has increased continuously from 24.8% to nearly 50% [17]. Given that the prognosis of EGC is excellent, attention is being focused on the QoL of these patients after the operation. For this reason, laparoscopic gastrectomy has emerged as an alternative treatment option for EGC and many studies have reported early safety results and the short-term benefits of that procedure. However, most of the reports on laparoscopic gastrectomy are retrospective and the randomized controlled trials that are available have many limitations such as being non-multicenter trials, having small sample sizes, generating conflicting results, etc. [2-6,16,18,19]. To our knowledge, the present study will be the first large-scale randomized controlled trial that assesses the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer.

Although there is solid evidence supporting the shortterm efficacy of laparoscopic gastrectomy for EGC, there is little information about its long-term efficacy. The Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group reported a multicenter study of the oncologic outcomes after laparoscopic gastrectomy for EGC in Japan [20]. In total, 1,294 patients underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy. The 5-year disease-free survival rates were 99.8%, 98.7%, and 85.7% for stage IA, IB, and II disease, respectively. The median follow-up period was 36 months. In Korea, Song et al. [11] retrospectively reviewed multicenter data to assess the timing and patterns of disease recurrence. In a 41-month follow-up, the incidence of disease recurrence was 1.6% in patients with EGC and 13.4% in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Advanced T-classification and lymph node metastasis were risk factors for recurrence. The authors concluded that the long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy were satisfactory and similar to those of open gastrectomy. Moreover, a single-center study by Hwang et al. [21] of 197 patients who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy revealed that the actual 3 years disease-free survival rates for EGC and AGC were 98.8% and 79.1%, respectively. In addition, when the single-center study of Pak et al. [22] examined the long-term oncologic outcomes of 714 consecutive laparoscopic gastrectomies for gastric cancer, the 5-year relapse-free survival rates were 95.8%, 83.4%, and 46.4% for stage I, II, and III disease, respectively while the 5-year overall survival rates were 96.4%, 83.1%, and 50.2%, respectively. The independent risk factors for recurrence were T stage and N stage. For survival, age, T stage, and N stage were statistically independent prognostic factors. The authors concluded that laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer had acceptable long-term oncologic outcomes that were comparable to those of conventional open surgery.

To date, seven randomized controlled trials have compared laparoscopic gastrectomy with open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. In all trials, LADG was compared to ODG [2-4,16-18,23]. Six of the trials only enrolled patients with clinically diagnosed EGC. One of the trials reported a 5-year follow-up of 59 patients with EGC or AGC; 29 underwent open subtotal gastrectomy, and 30 underwent laparoscopic resection [2]. The 5-year overall survival rates for open gastrectomy and laparoscopic gastrectomy were 55.7% and 58.9%, respectively, while the 5-year disease-free survival rates of the two groups were 54.8% and 57.3%, respectively. The authors concluded that laparoscopic radical subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer is a feasible and safe oncological procedure supported by long-term results similar to those obtained with an open surgery. Currently, the Gastric Cancer Surgical Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG 0912) and the KLASS group (KLASS 01) are conducting multi-institutional prospective randomized controlled phase III trials to compare laparoscopic gastrectomy with open gastrectomy. A separate phase III study for evaluating the feasibility of laparoscopic surgery in advanced gastric cancer is also underway in Korea (KLASS 02).

In summary, large multicenter randomized controlled trials are still required to determine whether there are significant and quantifiable differences between laparoscopic gastrectomy and open gastrectomy. The KLASS 01 trial is the first large multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial that will investigate whether laparoscopic surgery can improve patient QoL without compromising overall survival. The findings from this trial have the potential to change clinical practice in treating EGC.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–237. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000151892.35922.f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi H, Ochiai T, Shimada H, Gunji Y. Prospective randomized study of open versus laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with extraperigastric lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1172–1176. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery. 2002;131(1 Suppl):S306–S311. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.120115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MC, Kim KH, Kim HH, Jung GJ. Comparison of laparoscopy-assisted by conventional open distal gastrectomy and extraperigastric lymph node dissection in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:90–94. doi: 10.1002/jso.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strong VE, Devaud N, Allen PJ, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Coit D. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1507–1513. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MC, Kim W, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Ryu SY, Song KY, et al. Risk factors associated with complication following laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a largescale Korean multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2692–2700. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0075-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HJ, Kim HH, Kim MC, Ryu SY, Kim W, Song KY, et al. The impact of a high body mass index on laparoscopy assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2473–2479. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong GA, Cho GS, Kim HH, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Song KY. Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Surgery. 2009;146:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho GS, Kim W, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Kim MC, Ryu SY. Multicentre study of the safety of laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in the elderly. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1437–1442. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song J, Lee HJ, Cho GS, Han SU, Kim MC, Ryu SW, et al. Recurrence following laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a multicenter retrospective analysis of 1,417 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1777–1786. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0932-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park do J, Han SU, Hyung WJ, Kim MC, Kim W, Ryu SY, et al. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a large-scale multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1548–1553. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition - Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fayers P, Bottomley A EORTC Quality of Life Group, Quality of Life Unit. Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(Suppl 4):S125–S133. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn DW, Park JH. Effects of thought suppression and self-disclosure about the stressful life event on well-being and health. Korean J Health Psychol. 2005;10:183–209. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report: a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized Trial (KLASS Trial) Ann Surg. 2010;251:417–420. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cc8f6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, Jeong SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, et al. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg. 2011;98:255–260. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721–727. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185e62e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:168–173. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8808-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group. A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:68–72. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225364.03133.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang SH, Park do J, Jee YS, Kim MC, Kim HH, Lee HJ, et al. Actual 3-year survival after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2009;144:559–564. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pak KH, Hyung WJ, Son T, Obama K, Woo Y, Kim HI, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of 714 consecutive laparoscopic gastrectomies for gastric cancer: results from the 7-year experience of a single institute. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:130–136. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii K, Sonoda K, Izumi K, Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S. T lymphocyte subsets and Th1/Th2 balance after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1440–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]