Abstract

Excessive generation of superoxide and mitochondrial dysfunction has been described as being important events during ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. Our laboratory has demonstrated that manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), a major mitochondrial antioxidant that eliminates superoxide, is inactivated during renal transplantation and renal I/R and precedes development of renal failure. We hypothesized that MnSOD knockdown in the kidney augments renal damage during renal I/R. Using newly characterized kidney-specific MnSOD knockout (KO) mice the extent of renal damage and oxidant production after I/R was evaluated. These KO mice (without I/R) exhibited low expression and activity of MnSOD in the distal nephrons, had altered renal morphology, increased oxidant production, but surprisingly showed no alteration in renal function. After I/R the MnSOD KO mice showed similar levels of injury to the distal nephrons when compared with wild-type mice. Moreover, renal function, MnSOD activity, and tubular cell death were not significantly altered between the two genotypes after I/R. Interestingly, MnSOD KO alone increased autophagosome formation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and DNA replication/repair within the distal nephrons. These findings suggest that the chronic oxidative stress as a result of MnSOD knockdown induced multiple coordinated cell survival signals including autophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis, which protected the kidney against the acute oxidative stress following I/R.

Keywords: ischemia-reperfusion, manganese superoxide dismutase, oxidative stress, autophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis

acute kidney injury (aki) is one of the major causes of renal failure. Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, an event that occurs after a transient drop in total or regional blood flow to the kidney, is the most frequent intrarenal process of AKI in both native and transplanted kidneys (1, 7, 14). The pathogenesis of renal I/R injury is multifactorial; clearly oxidative stress and mitochondrial alteration/dysfunction are notable mechanisms (4, 6, 7, 15, 59, 65). Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) or SOD2 is a major mitochondrial antioxidant, which scavenges superoxide radicals that are generated within the mitochondria. Complete loss of this enzyme results in massive oxidative stress leading to neonatal death as evidenced from complete MnSOD KO mice (33, 36). Numerous studies have reported the loss of MnSOD enzyme activity following I/R within the heart (2, 11, 26, 39, 61), liver (23, 48), and kidney (17). In fact, our laboratory showed that using the rodent I/R model, MnSOD was inactivated prior to the onset of renal damage, which suggests that oxidant generation/mitochondrial damage are upstream to renal damage (15). Thus it is logical to try and develop strategies to intervene with excessive generation of mitochondrial oxidants. Overexpression (endogenous or exogenous) or induction of MnSOD has been shown to offer protection from I/R-induced cellular damage in the heart, brain, liver, and kidney (11, 29, 47, 48, 61). We and others have shown that ROS scavengers significantly protect against the renal I/R injury (8, 52, 63). Thus it is clear that mitochondrial superoxide plays a role in the pathogenesis of I/R injury; however, direct evidence whether loss of MnSOD enzyme activity actually initiates renal cell injury during I/R is lacking.

Recently, we developed and characterized a novel kidney-specific MnSOD KO mouse line that exhibited low MnSOD expression and activity within the distal nephron (distal tubules, loops of Henle, and collecting ducts), displayed increased renal injury (tubular dilation, cell swelling, casts in lumen) and oxidant production (nitrotyrosine accumulation) even without I/R (44). Therefore, we hypothesized that these MnSOD KO mice will sustain greater renal damage and will exacerbate overt renal function following renal I/R. MnSOD knockdown within the distal nephron did not aggravate cellular damage and overall renal function following I/R. Interestingly, the chronic oxidative stress as a result of MnSOD KO (without I/R) was found to induce autophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis within the distal nephron, which could explain the lack of additive injury following I/R.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The kidney-specific MnSOD knockout (KO) mice and littermate wild-type (WT) controls (Kidney Cre) mice were used in this study as recently described (44). MnSOD KO mice were generated by crossing Ksp-cadherin-Cre mice (57) that express cre specifically in distal nephrons (distal tubules, loops of Henle, and collecting ducts) with MnSOD flox mice (24). These novel kidney-specific MnSOD KO mice exhibit low expression and activity of MnSOD in distal nephrons (distal tubule, loops of Henle, and collecting duct), have altered renal morphology, display increased oxidant production (nitrotyrosine) in the kidney, but surprisingly show no alteration in renal function. Mice were maintained according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). All of the animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

I/R Injury

I/R injury surgery was done in mice as described (52). Briefly, a right nephrectomy was performed so that renal function reflects the function of the left kidney alone. The left renal artery and vein were clamped for 40 min and then released. At the end of the reperfusion (18 h), the animals were anesthetized (isoflurane), the left kidney removed, and blood collected from the inferior vena cava.

Experimental Groups

I/R group.

Mice were subjected to a right nephrectomy and renal artery occlusion (40 min) followed by 18 h reperfusion (n = 7; both WT and MnSOD KO strains). Another group of mice were subjected to a shorter (20 min) ischemic period.

Sham-operated group.

Mice underwent identical surgery (nephrectomy), but without the I/R episode (n = 7).

Serum Creatinine Assay

Serum creatinine was determined using a modified Jaffe's method (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI) in a Cobas Mira clinical analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The values were expressed as milligrams per deciliter.

Kidney Morphology Based on Periodic Acid-Schiff Staining

Renal sections were assessed for tissue injury using the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction as described (44). Evaluation was conducted (in a blinded fashion) based on the following criteria: tubular dilation; casts in lumen; cell swelling/enlargement; loss of tubular brush border; and epithelial cell flattening. All parameters were graded on a scale of 0 = no lesion; 1 = minimal change; 2 = mild change; and 3 = prominent change. Cumulative comparisons were made between the genotypes (WT and MnSOD KO). In addition, the same sections were evaluated for intensity of damage in the proximal tubule vs. the distal nephron segments. The final renal injury scores of proximal tubules and distal nephrons were averaged and also reported. All images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope (Q Capture imaging and Nikons Elements software).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was done as described (44). The primary antibodies against anti-nitrotyrosine (1:6,000; Millipore), anti-LC3 AB (1:10,000; NOVUS), anti-MnSOD, (1:250, Millipore), anti-OxPhos Complex IV subunit I (COXI, 1:1,000; Invitrogen), anti-ATP5B (1:500; Santa Cruz), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (1:200; Dako), and anti-neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL, 1:500; Abcam) were prepared in antibody diluent solution (0.5% nonfat dry milk and 1% BSA in TBS) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The specificity of nitrotyrosine antibody binding in the renal tissue was confirmed by blocking the antibody with 3-nitrotyrosine (10 mM). Immunoreactivity was detected by Dako Envision+ System-HRP or Animal Research Kit (Dako). Counterstaining was performed with Mayer's Hematoxylin (Electron Microscopy Science). All images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope (Q Capture imaging and Nikons Elements software). Semiquantitative evaluation on nitrotyrosine staining was performed as described (44).

TUNEL Assay

For visualization of apoptotic cells in situ terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) method was utilized according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (TACS TdT Kit, R&D Systems). Counterstaining was performed with methyl green solution. Seven different fields (20X) (3 cortex, 2 outer medulla, 2 inner medulla) from each mouse kidney section were considered for evaluation. TUNEL-positive cells from each field were grouped in two nephron segments, namely proximal tubule (glomerulus and proximal tubules) and distal nephrons (distal tubule, loops of Henle, and collecting ducts) and the average was reported.

Renal Extract Preparation

Renal extracts were made from frozen tissue as described (52). Protein concentrations were determined by Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce).

Western Blot Analysis

Western analysis was performed using antibodies against LC3 A/B (1:1,000, Novus) which detects LC3 I and II proteins; Atg5 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling), which detects Atg5 and Atg12 complex; and GAPDH (1:1,000, Millipore). Probed membranes were washed three times, and immune-reactive proteins were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence.

MnSOD Activity

Enzymatic activity of MnSOD was determined in renal extracts by the cytochrome c reduction method in the presence of 1 mM KCN to inhibit Cu,Zn SOD activity (40).

Citrate Synthase Activity Assay

Citrate synthase (CS) activity was determined in renal extracts following the reduction of 5,5-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoicacid) (Sigma) in a coupled reaction with acetyl coenzyme A (Roche) and oxaloacetate (Sigma) at 412 nm (45).

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as means ± SE. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences in mean between two groups at 95% level of confidence using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software. Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Renal Dysfunction

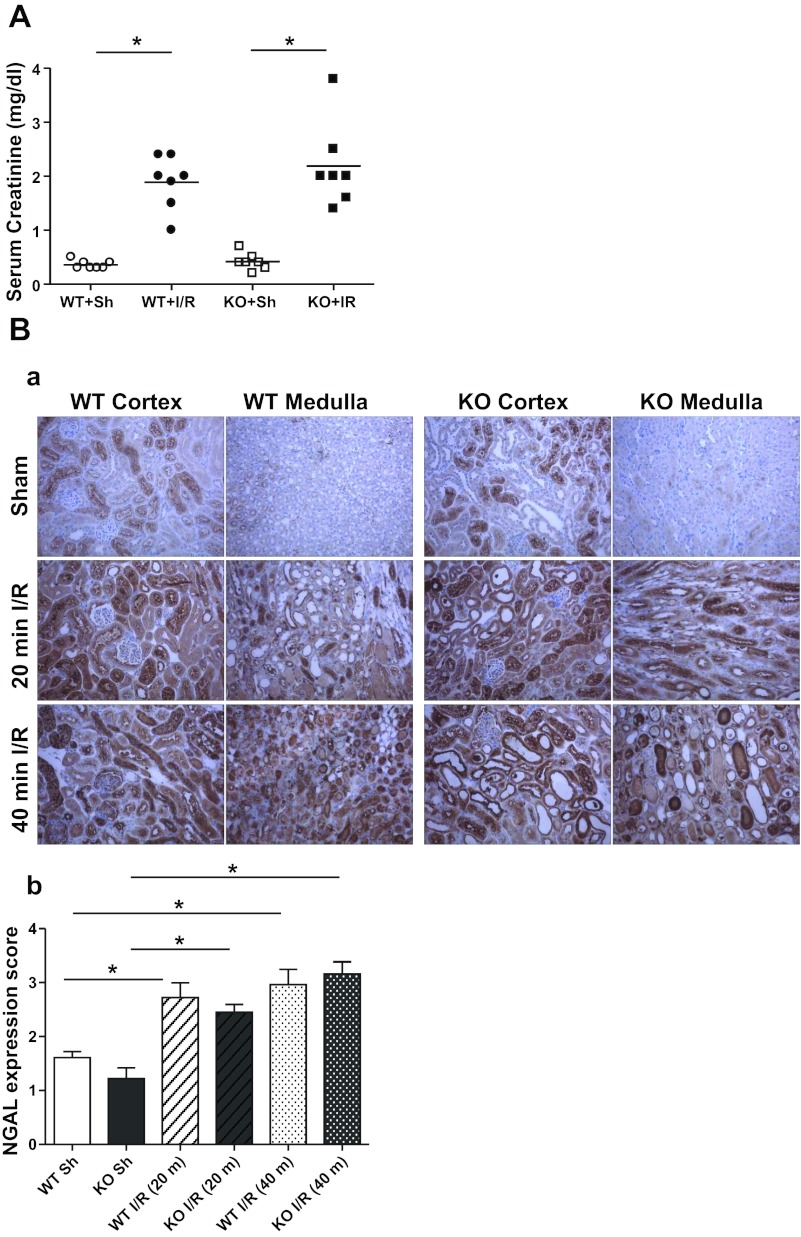

Mice were exposed to 40 min ischemia followed by 18 h of reperfusion. As expected, both kidney-specific MnSOD KO (KO) and Kidney Cre (wild type, WT) mice showed significant elevation of serum creatinine after I/R compared with the respective sham (right nephrectomy alone) (Fig. 1A). However, the serum creatinine levels after I/R were not significantly different between the two genotypes. Consistent with the serum creatinine data, another tubular injury marker, NGAL expression, was equally increased following I/R (40 min) in both genotypes (Fig. 1B). A milder model of ischemia (20 min instead of 40 min) was also utilized to determine whether less severe ischemia might permit discrimination of renal injury between genotypes. Similar to 40 min ischemia, there was no difference in the serum creatinine (mg/dl; WT, 0.77 ± 0.27 vs. KO, 0.57 ± 0.22) or NGAL expression after 20 min ischemia.

Fig. 1.

A: effect of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) knockdown on serum creatinine levels following I/R. Serum creatinine was determined in wild-type (WT) and MnSOD knockout (KO) mice after receiving 40 min ischemia and 18 h reperfusion. Values are expressed as means ± SE [n = 7 for sham (Sh); n = 7 for ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)]. B: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) expression following I/R injury. Ba: representative 200× micrographs show significant levels of NGAL expression in cortical and medullar regions of mouse kidney following mild (20 min) and severe (40 min) I/R. Bb: expression level of NGAL was evaluated semiquantitatively and scored. Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 4 for sham; n = 6 for I/R). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

Histological Evidence of Renal Damage

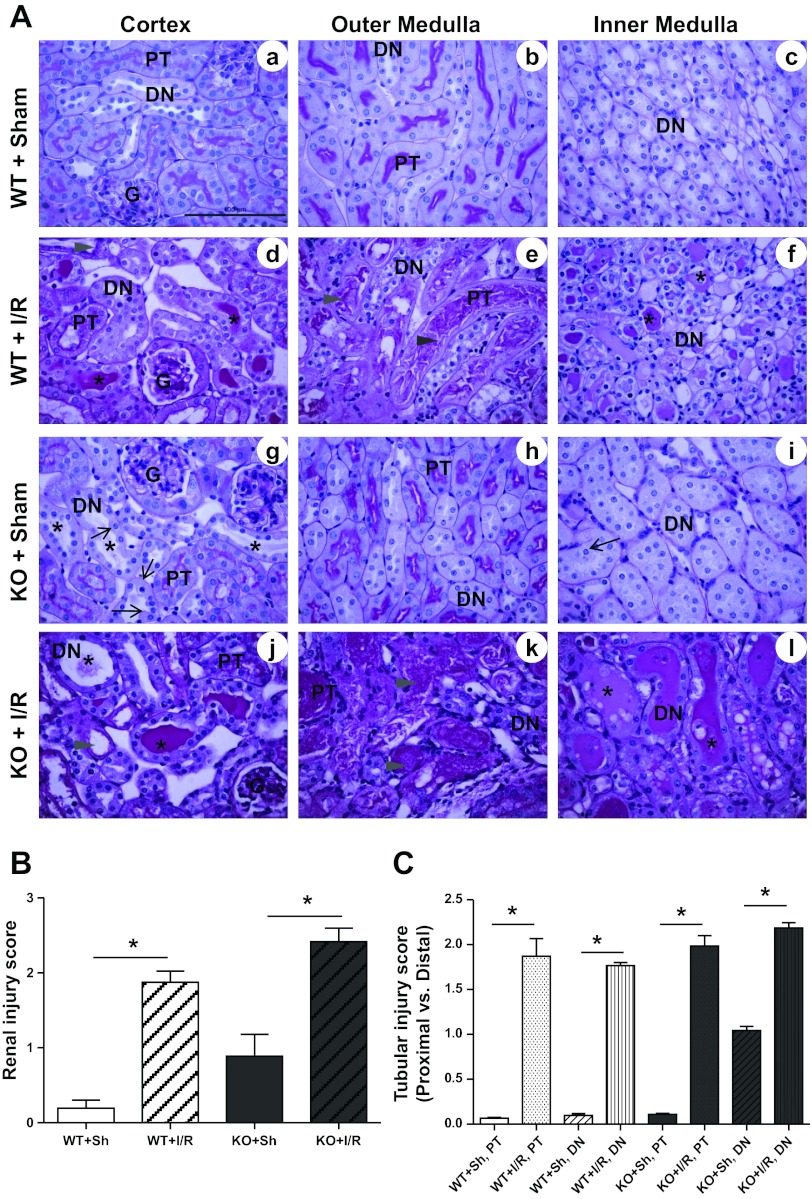

Although MnSOD knockdown failed to increase serum creatinine or NGAL levels after I/R compared with WT animals, it was important to assess the amount of tubular damage contributed by MnSOD loss using a histochemical approach, especially since MnSOD knockdown is only observed in the distal nephrons. As shown in previous reports (15, 52) and in these experiments, I/R induced marked tubular damage in both WT and MnSOD KO mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Similar to our earlier report (44), sham kidneys of KO mice showed greater cast formation, tubular dilation, and cell swelling (Fig. 2A, g–i) compared with sham WT mice (Fig. 2A, a–c). Since, MnSOD knockdown was observed only in distal nephrons, a separate evaluation of different nephron segments with regard to MnSOD expression was performed, which showed proximal tubules and distal nephrons contributed equally to I/R-mediated renal damage (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Effect of MnSOD knockdown on total tubular injury after I/R. A: representative 400× micrographs of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining in renal cortex and medulla of WT and KO mice after sham and I/R surgery (asterisks, casts in lumen; arrowhead, tubular necrosis; thin arrow, cell swelling). Representative bar indicates 100 μm. Abbreviations: G, glomerulus; PT, proximal tubules; DN, distal nephrons. B: graph shows the pathological scoring for total tubular injury including casts in lumen, tubular dilation, loss of brush border, tubular necrosis, cell swelling, and epithelial cell flattening. Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 4 for sham; n = 6 for I/R). C: tubular injury score in proximal tubules and distal nephrons (distal tubule, loops of Henle, and collecting ducts). Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 4 for sham; n = 6 for I/R). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

MnSOD Inactivation

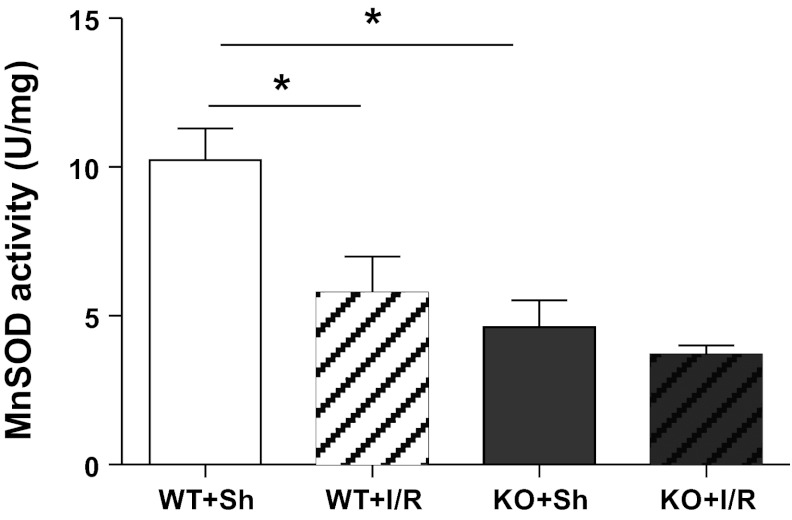

As expected the sham kidneys of the MnSOD KO mice showed ∼60% reduction in MnSOD enzymatic activity (Fig. 3). In addition, I/R induced MnSOD inactivation in WT mice (Fig. 3); however, no significant difference was noted following I/R in the KO mice.

Fig. 3.

MnSOD activity following I/R. MnSOD activity was determined in total renal homogenates using the cytochrome c reduction method. WT mice showed significant MnSOD activity loss after I/R. MnSOD KO mice, which showed ∼60% activity loss prior to I/R, did not decline further after I/R. Error bar represents mean ± SE (n = 3 for sham; n = 6 for I/R). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

Nitrotyrosine Protein Accumulation

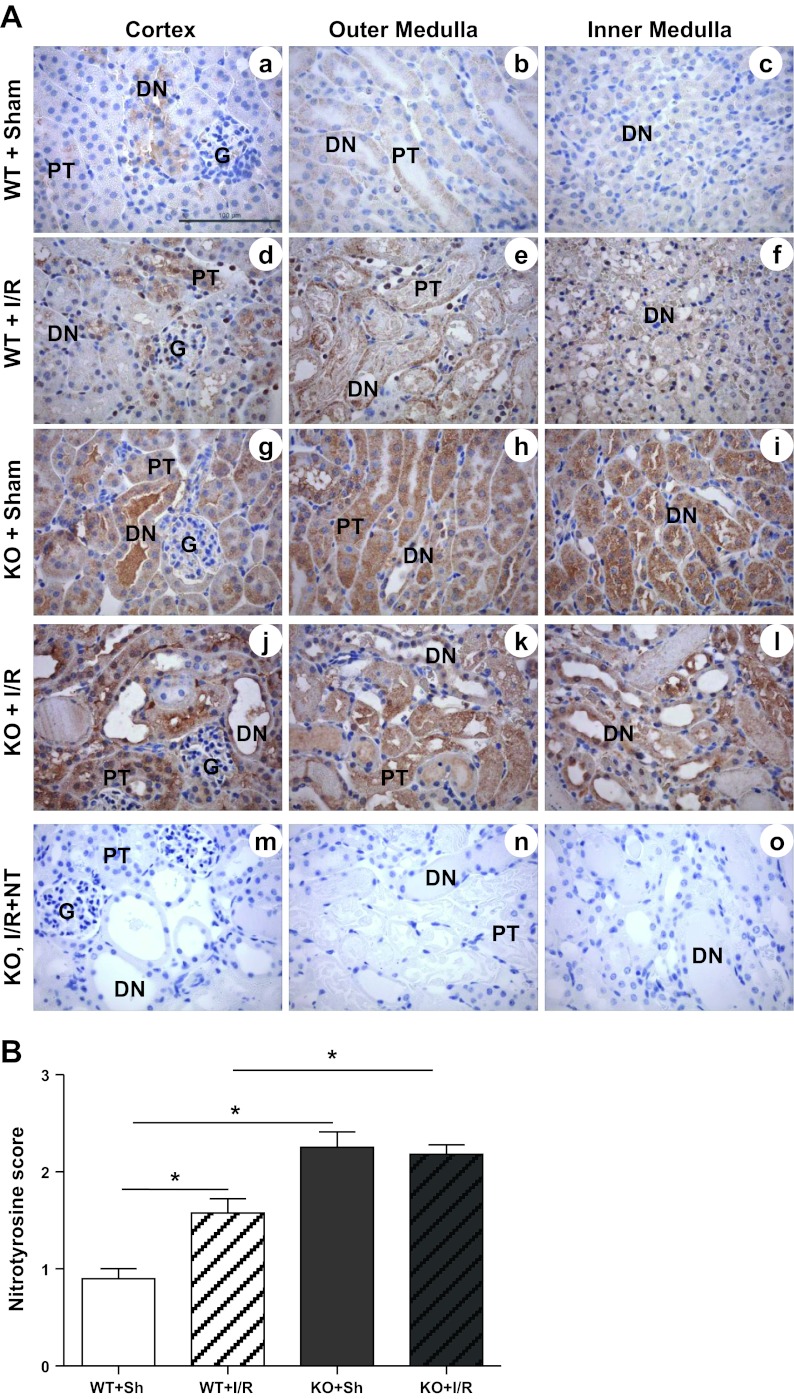

Previous reports from our laboratory and others have shown the accumulation of nitrotyrosine protein (marker of oxidative stress) in the kidney after I/R (15, 32, 36, 47, 52). Therefore, to evaluate whether MnSOD knockdown augmented the accumulation of nitrotyrosine protein following I/R, immunohistochemical localization of nitrotyrosine was performed. Similar to the previous reports, I/R induced significant accumulation of nitrotyrosine protein in the WT mice (Fig. 4, A, a–f; and B). Consistent with our earlier report on MnSOD KO mice (44), nitrotyrosine was significantly increased in sham kidneys from MnSOD KO mice (Fig. 4, A, g–i; and B). MnSOD KO mice did not show a further increase in nitrotyrosine following I/R. Interestingly, even though a significant level of nitrotyrosine staining was observed following I/R in the WT mice (Fig. 4A, d–f), this increased nitrotyrosine staining was significantly lower than the sham (Fig. 4A, g–i) or I/R kidneys (Fig. 4A, j–l) of KO mice.

Fig. 4.

Effect of MnSOD knockdown on protein nitration (oxidative stress) after I/R. A, a–o: representative 400× micrographs of nitrotyrosine immunostaining are shown. The specificity of nitrotyrosine binding in the renal tissue was confirmed by blocking the antibody with 3′-nitrotyrosine (10 mM) using sections of KO kidney after I/R (m–o). Bar indicates 100 μm. B: expression level of nitrotyrosine was evaluated semiquantitatively and scored. Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 4 for sham; n = 6 for I/R). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

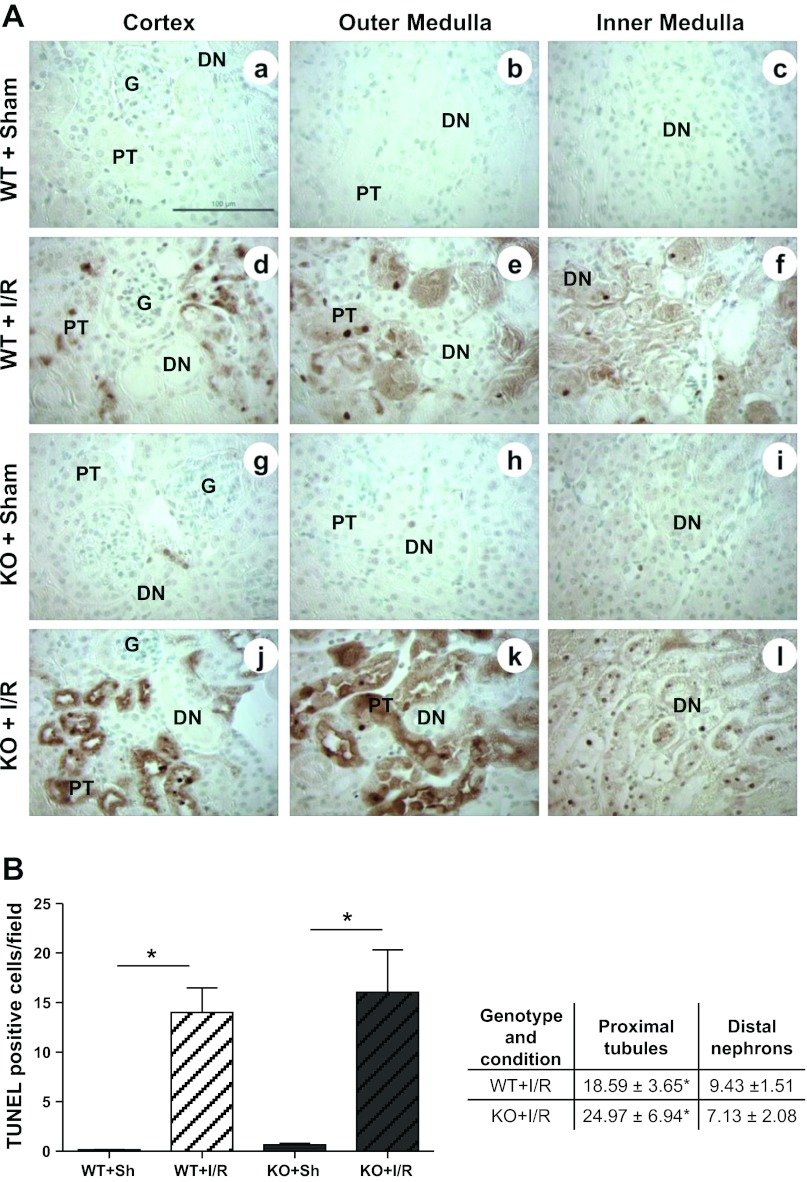

Renal Cell Death

To assess whether MnSOD knockdown in distal nephrons exacerbate renal cell death following I/R, in situ TUNEL assay was performed. As expected, the total number of TUNEL-positive nuclei was significantly increased after I/R in both genotypes (Fig. 5, A and B). However, increased TUNEL-positive nuclei after I/R was not significantly different between the two genotypes. To determine whether cell death showed a differential effect between different nephron segments, TUNEL-positive nuclei were counted in two different segments of nephrons: 1) proximal tubules including the glomerulus, and 2) distal nephrons (distal tubules, loops of Henle and collecting ducts). Proximal tubules showed a greater number of TUNEL-positive cells compared with the distal nephron segments following I/R; however, no difference between genotypes after I/R was observed.

Fig. 5.

MnSOD knockdown failed to augment apoptosis induction after I/R. A, a–l: representative 400× micrographs show TUNEL-positive brown nuclei (apoptotic cells) from cortex, outer medulla and inner medulla regions of sham and I/R kidneys. Bar indicates 100 μm. B: TUNEL-positive cells were counted in 7 different fields (200×), and the average was reported (left panel). Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 3 for sham; n = 5 for I/R). Right panel shows tabulation of TUNEL-positive nuclei counted in different segments of nephrons, namely proximal tubules (proximal tubules and glomerulus) and distal nephrons (distal tubules, loops of Henle, and collecting ducts). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

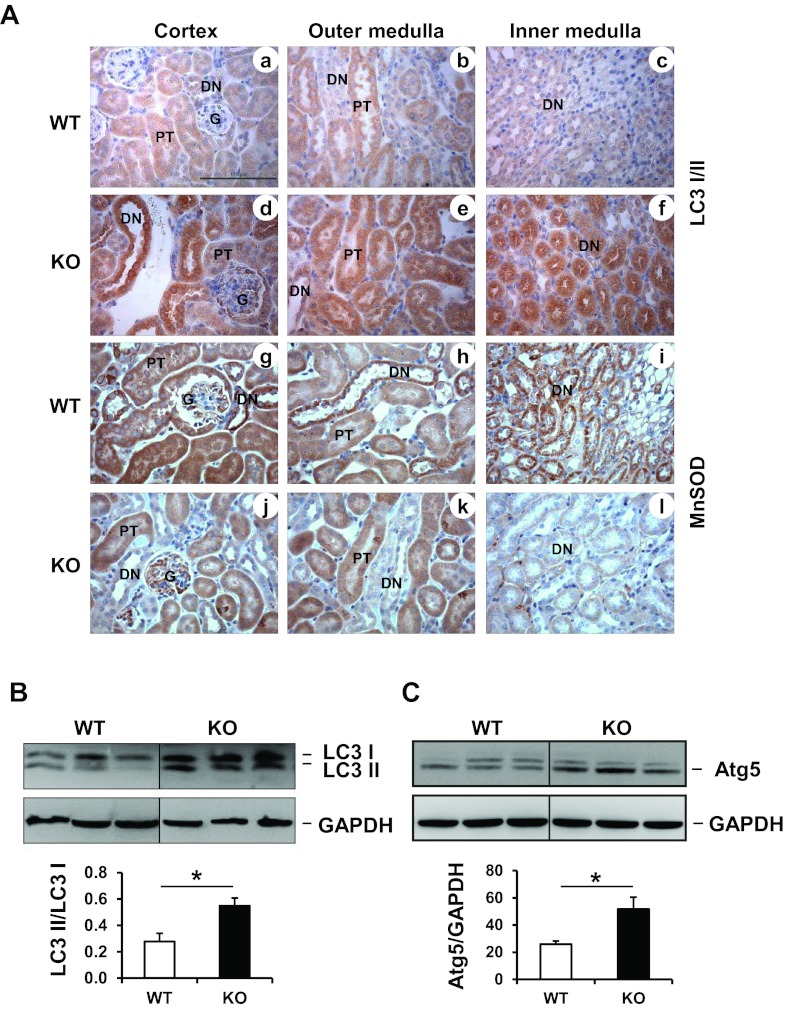

Autophagy

All of the above results indicated that the loss of MnSOD in distal nephrons failed to augment renal I/R-mediated cell death, or renal dysfunction. This prompted the development of our alternate hypothesis that MnSOD knockdown could alter cell protective mechanisms within discrete renal cells, which might blunt renal dysfunction following I/R. Mitochondrial superoxide has been shown to induce autophagy pathways (9, 34). Autophagy involves lysosome-dependent degradation of damaged cytoplasmic constituents (cytotoxic protein aggregates and dysfunctional organelles) sequestered by autophagosomes (18, 41, 43, 64). During stress or nutrient-deprived conditions, the cytoplasmic form of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3 I) is processed into a lipidated LC3 II form that is incorporated into the phagophore membrane to form an autophagosome (27, 28). Therefore, LC3 II/LC3I ratio is considered as a marker of autophagosome formation. Since MnSOD is deleted from distal nephron segment of the KO mouse kidney, LC3 localization using immunohistochemistry was evaluated with regard to MnSOD expression. Interestingly, immunohistochemistry revealed that total LC3 protein (LC3 I and LC3 II) was heavily localized to the distal nephrons, which exhibited low MnSOD protein in the KO kidney controls (without I/R) [Fig. 6 A, a–f (for LC3) and g–l (for MnSOD)]. Only a few proximal tubules in the cortex or outer medullar region showed increase of total LC3 protein. LC3 Western blot evaluation showed a significant conversion of LC3 I to LC3 II in the kidneys from sham KO mice compared with the WT kidneys (Fig. 6B). Similar to the LC3 protein, Atg5 Western blot showed increased level of Atg5 (a marker for autophagosome initiation complex) (42, 62) in the KO mice (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

MnSOD knockdown triggers autophagosome formation in sham kidneys. A: a–f show representative micrographs of total LC 3 (I and II) immunostaining in WT and MnSOD KO sham kidneys; g–l shows representative micrographs of MnSOD expression in sham kidneys. Bar indicates 100 μm. B: Western blot detection for LC3 I and II from renal homogenate of control kidneys. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Graph represents values after densitometric quantification (LC3II/LC3I) of Western blot results. LC3 II is increased in MnSOD KO sham kidneys. C: Western blot detection for Atg5 from renal homogenate of control kidneys. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Atg5 is increased in MnSOD KO sham kidneys. Graph represents values after densitometric quantification of Western blot results. Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 3). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

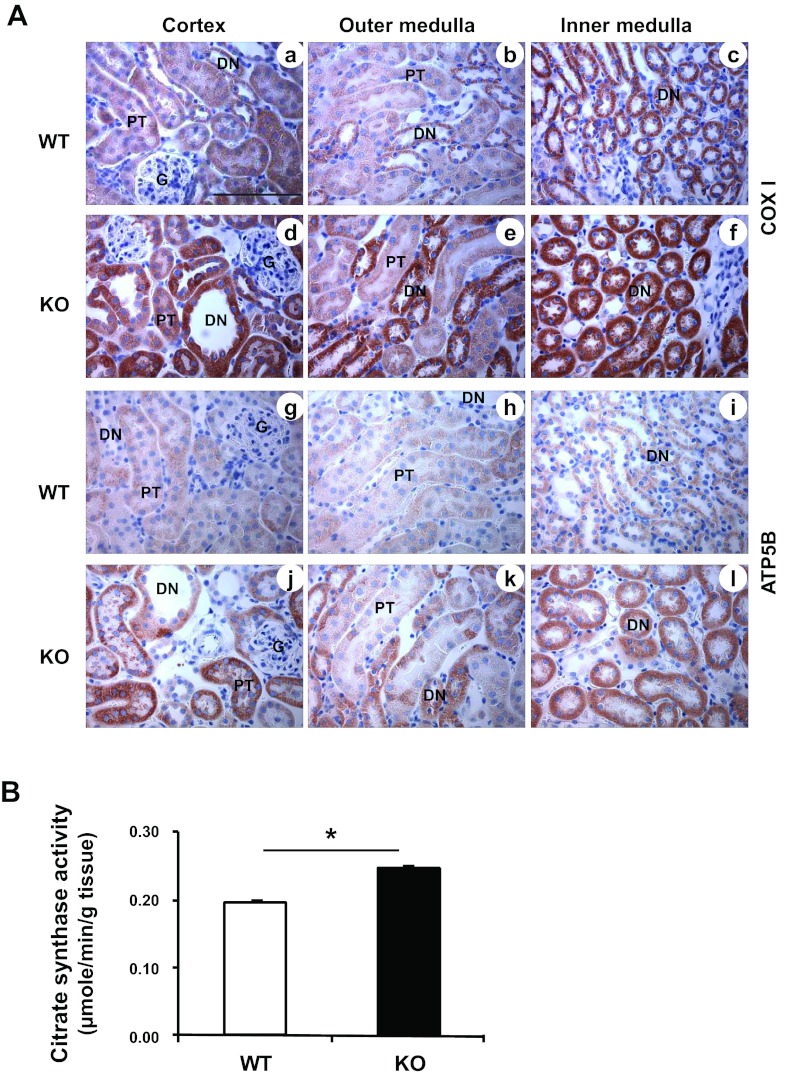

Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Mitochondrial biogenesis is initiated by cells as an adaptive response during stressful conditions, including oxidative stress, to maintain cellular energy demand. This process also helps restore mitochondrial mass and function following degradation of mitochondria (mitophagy) (12, 46, 67). Since the kidney-specific MnSOD KO mice displayed normal renal function despite mitochondrial oxidative stress burden (44), it is possible that the MnSOD knockdown in the renal cells triggered mitochondrial alterations to compensate for the elevated cellular stress. To further confirm that MnSOD knockdown altered mitochondrial protein synthesis, immunohistochemical detection of both, a mitochondrial DNA encoded mitochondrial protein (Complex IV subunit I or COXI), and a nuclear DNA encoded mitochondrial protein (ATP5B), was performed. Figure 7A shows endogenous levels of COXI (Fig. 7A, a–c), and ATP5B (Fig. 7A, g–i) proteins in the renal tissue of WT mice. The MnSOD KO mice showed increased COXI [Fig. 7A, d–f (KO mice)] and ATP5B [Fig. 7A, j–l (KO mice)] levels compared with WT mice. Similar to the LC3 expression pattern (Fig. 6A, a–f), the elevated COXI and ATP5B levels were localized to the distal nephron where significant MnSOD knockdown was evident as shown in Fig. 6A, g–l. CS, a nuclear genome-encoded mitochondrial matrix protein, functions as a pace-making enzyme in the citric acid cycle. CS activity is considered a biomarker for mitochondrial mass and function, and thus an increase in CS activity indicates mitochondrial biogenesis (66). Interestingly, renal homogenates from MnSOD KO mice showed ∼20% increase in citrate synthase activity compared with that of WT mice (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial biogenesis following MnSOD knockdown. A: Representative micrographs of mitochondrial proteins (n = 6); a–f show Complex IV subunit I (COXI, mitochondrial DNA encoded), and g–l show Complex V subunit (ATP5B, nuclear DNA encoded). Representative bar indicates 100 μm. B: citrate synthase activity showed ∼20% increase in MnSOD KO control kidney compared with the WT control kidney. Error bar indicates mean ± SE (n = 5). *Means are significantly different, P < 0.05.

Proliferation

Since MnSOD KO mice (without I/R) did not show TUNEL-positive cells in the distal nephrons (Fig. 5), we evaluated whether these KO mice displayed DNA replication/repair within the distal nephrons. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a central protein for both DNA replication and repair and is used to assess cellular proliferation (19, 53, 58). Interestingly, MnSOD knockdown induced significant increase of PCNA-positive nuclei in distal nephrons (Table 1).

Table 1.

PCNA expression in kidney-specific MnSOD KO mice

| Nephron Segment | WT | KO |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule and glomerulus | 46 ± 11.71 | 36.50 ± 8.71 |

| Distal nephron | 65.33 ± 10.47 | 160.66 ± 38.22*† |

Values are presented as means ± SE. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-stained immunohistochemical slides from control kidneys were further stained with periodic acid-Schiff reagent. PCNA-positive nuclei were counted in two segments of nephron: 1) proximal tubules and glomeruli, and 2) distal nephron (distal tubule, loops of Henle, collecting duct), considering 10 different fields per mice (n = 6, each group).

P < 0.05, wild-type (WT) distal nephron vs. MnSOD knockout (KO) distal nephron;

P < 0.05, KO distal nephron vs. KO proximal tubule and glomerulus.

DISCUSSION

Recently, we showed in kidney-specific MnSOD KO mice that the oxidative stress due to decreased MnSOD activity triggered sublethal tubular injury (tubular dilation, cell swelling, and casts formation) in the distal nephrons without an increase in apoptosis/necrosis (44). In this report these novel MnSOD KO mice were exposed to I/R to assess the contribution of reduced MnSOD activity in triggering renal damage during I/R injury. Contrary to our expectation, MnSOD knockdown in the distal nephrons did not augment renal dysfunction, oxidant production, or cell death following I/R (Figs. 1, 4, and 5). These results lead to the obvious question as to why kidneys were not more injured in the MnSOD KO mice following I/R?

Recently, ROS have been shown to induce autophagy (a self-degradation process), which can modulate the fate of the cell during oxidative stress or nutrient deprivation (34, 54–56). In vitro studies show that superoxide is a major ROS regulating autophagy, and this pathway is altered by MnSOD (9, 10). Therefore, we sought to determine whether MnSOD knockdown led to induction of autophagy in our kidney model. Intriguingly, loss of MnSOD activity in the distal nephrons accounted for the induction of autophagosomes formation (increase of LC3II/ LC3I ratio and Atg5) in the tubular compartments of the KO kidney (without I/R) (Fig. 6). Autophagy is often enhanced following renal I/R and is considered to be renoprotective (13, 25). However, a few reports indicate that high turnover of autophagy is detrimental to renal cells after I/R (35, 60). Conversely, we believe that the extent of autophagy observed following chronic MnSOD knockdown was not severe enough to induce renal cell death, since a significant increase of LC3 II and Atg5 (without I/R) in the MnSOD KO mice did not increase TUNEL staining compared with the WT mice (Figs. 5 and 6). These data suggest that mitochondrial oxidants following MnSOD knockdown might protect the kidney from I/R-mediated damage through induction of autophagy.

Normally, ROS-forming mitochondria are detrimental to cells; therefore, for quality control, these defective mitochondria are frequently cleared by autophagy/mitophagy pathway, followed by induction of mitochondrial biogenesis to restore mitochondrial mass and function (30, 31, 49, 50). Mitochondrial biogenesis is a process of growth and division of preexisting mitochondria that involves the coordinated action of both the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes (67). Since MnSOD knockdown lead to increased autophagy, it was equally important to determine whether mitochondrial biogenesis was also increased. Citrate synthase (CS) activity, a common indicator of mitochondrial mass, was increased (∼20%) in renal homogenates of MnSOD KO mice (Fig. 7A). Increased CS activity has been observed during pathological conditions to compensate for disrupted mitochondrial mass/function (66). Since normal functioning mitochondria depend both on mitochondrial- and nuclear-DNA-encoded mitochondrial proteins, we evaluated ATP5B (nuclear encoded) and COX subunit I (mitochondrial encoded) protein expression following MnSOD knockdown. As clearly depicted in Fig. 7, both of these mitochondrial proteins were increased within the distal nephron, suggesting that loss of MnSOD in these cell types induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Some proximal tubules also exhibited induction of biogenesis; however, this was not as prevalent as the induction noted in the distal nephron segment. The literature suggests that proximal tubules are very sensitive to oxidative stress, especially in the outer medullar region. It is also known that there is a close cross-talk between proximal tubules and distal nephrons. We believe that the oxidative stress resulting from MnSOD knockdown in distal nephrons also influenced proximal tubules in these cortical and medullary regions, thereby triggering autophagy induction and weak biogenesis. Another interesting observation was the significant increase of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-positive nuclei in the distal nephrons of KO mice (Table 1). Besides replication, PCNA is also shown to be expressed in the nucleus during DNA repair (19). An increase in cellular proliferation could partially explain why these KO kidneys (without I/R) did not display TUNEL staining despite exhibition of significant oxidative stress in the distal nephrons.

Given the increased oxidative stress, autophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and proliferation (PCNA) observed in the MnSOD KO mice, it appears that the KO mice have stable autophagy/mitophagy, as well as compensatory mitochondrial biogenesis, and DNA replication/repair processes, which could explain the lack of augmented injury following I/R reported in the current study. In addition, these new findings can also help explain the lack of overt renal dysfunction in our distal nephron-specific MnSOD KO mouse model (44). This indicates that mitochondrial oxidants stimulate multiple but coordinated signaling pathways (nuclear and mitochondrial) to confer cellular resistance against oxidative stress in kidneys with reduced MnSOD activity. However, it is not clear yet how these multiple adaptive processes are coordinated. Future studies using the kidney-specific MnSOD KO mice are needed to address these important issues with regard to assessment of mitochondrial damage (e.g., mitochondrial DNA damage, electron transport chain dysfunction) which could initiate induction of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis.

Studies from tissue culture and animal models suggest that proximal tubules (specifically the S3 segment) are important targets of oxidative stress-mediated acute injury leading to tubular necrosis following I/R (3, 16, 37, 38). Consistent with these observations, both genotypes showed a similar level of tubular necrosis in the proximal tubules following I/R (Fig. 2, A and B), which is likely due to the lack of MnSOD knockdown in proximal tubules. Therefore, one limitation of this KO model was that it failed to assess the contribution of MnSOD activity within proximal tubules and glomeruli following I/R.

Generation of newer animal models that try to mimic clinical scenarios and outcomes could serve as invaluable tools to study pathological changes during diseases. This is the first in vivo kidney-specific MnSOD KO model that showed the ablation of the MnSOD gene within the distal nephron (44). In addition, the current study highlights the importance of comprehensive characterization of new transgenic mouse models. Clearly, this kidney-specific MnSOD KO model showed profound compensatory responses (autophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and cell proliferation) downstream to MnSOD knockdown, a finding that could result in erroneous conclusions regarding the impact related to MnSOD knockdown. Therefore, these kidney-specific MnSOD KO mice could serve as a unique model of chronic oxidative stress in studying the multifaceted pathobiology and signaling pathways that are involved with MnSOD loss/inactivation. Furthermore, this mouse model appeared to mimic the pathology associated with the obstructed kidney following I/R, which is characterized by dilated distal tubules and collecting ducts filled with cellular and acellular casts (5, 22). Surprisingly, this increase of tubular obstruction in the KO kidney did not cause additional renal dysfunction compared with WT mice (Fig. 1). This could be explained partly because of the distant anatomical location of distal nephrons to the glomerulus (51), and to the rapid regenerating power of distal nephrons in response to an acute insult or injury (5). Another possibility is the ability of distal nephron cells to produce hormones and growth factors that are sometimes essential for the survival/function of proximal tubule cells (20, 21). Nevertheless, these KO mice could possibly serve as a potential model in studying the pathobiology of acute renal obstruction in the distal nephrons following renal I/R and/or the oxidative stress.

In summary, MnSOD knockdown accounted for an increased sublethal tubular injury (evidenced as tubular dilations and casts formation in the lumen) in the distal nephrons of the MnSOD KO mice compared with the WT mice. However, in contrast to our hypothesis, these tubular injuries did not augment the renal dysfunction and cellular damage following I/R in MnSOD KO mice. Interestingly, evidence of increased autophagosome formation and mitochondrial biogenesis was observed in the distal nephrons of the MnSOD KO mice kidney (without I/R), correlating nicely with the loss of MnSOD. Clearly, these findings strongly suggest that the chronic oxidative stress as a result of MnSOD knockdown (without I/R) stimulated multiple coordinated cell survival strategies (autophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and proliferation), which likely offered continual resistance to the acute oxidative stress following I/R.

GRANTS

We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support (NIH Grant 1RO1DK0789361). Disclosure:

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.P. and L.A.M.-C. conception and design of research; N.P. performed experiments; N.P. and L.A.M.-C. analyzed data; N.P. and L.A.M.-C. interpreted results of experiments; N.P. prepared figures; N.P. drafted manuscript; N.P. and L.A.M.-C. edited and revised manuscript; N.P. and L.A.M.-C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Akira Marine for help in genotyping; and the UAMS Translational Pathology Shared Resource for the excellent service in processing paraffin-embedded tissue blocks.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abuelo JG. Current concepts—normotensive ischemic acute renal failure. N Engl J Med 357: 797–805, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asimakis GK, Lick S, Patterson C. Postischemic recovery of contractile function is impaired in SOD2(+/−) but not SOD1(+/−) mouse hearts. Circulation 105: 981–986, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 121: 4210–4221, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest 119: 1275–1285, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butt MJ, Tarantal AF, Jimenez DF, Matsell DG. Collecting duct epithelial-mesenchymal transition in fetal urinary tract obstruction. Kidney Int 72: 936–944, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castaneda MP, Swiatecka-Urban A, Mitsnefes MM, Feuerstein D, Kaskel FJ, Tellis V, Devarajan P. Activation of mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in human renal allografts after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation 76: 50–54, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chatterjee PK. Novel pharmacological approaches to the treatment of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury: a comprehensive review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 376: 1–43, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatterjee PK, Cuzzocrea S, Brown PA, Zacharowski K, Stewart KN, Mota-Filipe H, Thiemermann C. Tempol, a membrane-permeable radical scavenger, reduces oxidant stress-mediated renal dysfunction and injury in the rat. Kidney Int 58: 658–673, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ 16: 1040–1052, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Y, McMillan-Ward E, Kong J, Israels SJ, Gibson SB. Mitochondrial electron-transport-chain inhibitors of complexes I and II induce autophagic cell death mediated by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Sci 120: 4155–4166, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen ZY, Siu B, Ho YS, Vincent R, Chua CC, Hamdy RC, Chua BHL. Overexpression of MnSOD protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in transgenic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 30: 2281–2289, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chevtzoff C, Yoboue ED, Galinier A, Casteilla L, Daignan-Fornier B, Rigoulet M, Devin A. Reactive oxygen species-mediated regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 285: 1733–1742, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chien CT, Shyue SK, Lai MK. Bcl-xL augmentation potentially reduces ischemia/reperfusion induced proximal and distal tubular apoptosis and autophagy. Transplantation 84: 1183–1190, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choudhury D. Acute kidney injury: current perspectives. Postgrad Med 122: 29–40, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cruthirds DL, Novak L, Akhi KM, Sanders PW, Thompson JA, MacMillan-Crow LA. Mitochondrial targets of oxidative stress during renal ischemia/reperfusion. Arch Biochem Biophys 412: 27–33, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cuttle L, Zhang XJ, Endre ZH, Winterford C, Gobe GC. Bcl-X(L) translocation in renal tubular epithelial cells in vitro protects distal cells from oxidative stress. Kidney Int 59: 1779–1788, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dobashi K, Ghosh B, Orak JK, Singh I, Singh AK. Kidney ischemia-reperfusion: modulation of antioxidant defenses. Mol Cell Biochem 205: 1–11, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eskelinen EL, Saftig P. Autophagy: a lysosomal degradation pathway with a central role in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 664–673, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Essers J, Theil AF, Baldeyron C, van Cappellen WA, Houtsmuller AB, Kanaar R, Vermeulen W. Nuclear dynamics of PCNA in DNA replication and repair. Mol Cell Biol 25: 9350–9359, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gobe G, Zhang XJ, Cuttle L, Pat B, Willgoss D, Hancock J, Barnard R, Endre Z. Bcl-2 genes and growth factors in the pathology of ischaemic acute renal failure. Immunol Cell Biol 77: 279–286, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gobe GC, Johnson DW. Distal tubular epithelial cells of the kidney: Potential support for proximal tubular cell survival after renal injury. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39: 1551–1561, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grande MT, Lopez-Novoa JM. Fibroblast activation and myofibroblast generation in obstructive nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 319–328, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta M, Dobashi K, Greene EL, Orak JK, Singh I. Studies on hepatic injury and antioxidant enzyme activities in rat subcellular organelles following in vivo ischemia and reperfusion. Mol Cell Biochem 176: 337–347, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ikegami T, Suzuki Y, Shimizu T, Isono K, Koseki H, Shirasawa T. Model mice for tissue-specific deletion of the manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 296: 729–736, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jiang M, Liu K, Luo J, Dong Z. Autophagy is a renoprotective mechanism during in vitro hypoxia and in vivo ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol 176: 1181–1192, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jin ZQ, Zhou HZ, Cecchini G, Gray MO, Karliner JS. MnSOD in mouse heart: acute responses to ischemic preconditioning and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2986–H2994, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Oshitani-Okamoto S, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J Cell Sci 117: 2805–2812, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 19: 5720–5728, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keller JN, Kindy MS, Holtsberg FW, St Clair DK, Yen HC, Germeyer A, Steiner SM, Bruce-Keller AJ, Hutchins JB, Mattson MP. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase prevents neural apoptosis and reduces ischemic brain injury: suppression of peroxynitrite production, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci 18: 687–697, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim I, Lemasters JJ. Mitophagy selectively degrades individual damaged mitochondria after photoirradiation. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 1919–1928, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim I, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Lemasters JJ. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch Biochem Biophys 462: 245–253, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim J, Seok YM, Jung KJ, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species/oxidative stress contributes to progression of kidney fibrosis following transient ischemic injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F461–F470, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lebovitz RM, Zhang HJ, Vogel H, Cartwright J, Dionne L, Lu NF, Huang S, Matzuk MM. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9782–9787, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee J, Giordano S, Zhang J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem J 441: 523–540, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J Clin Invest 115: 2679–2688, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li YB, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson TL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Berger C, Chan PH, Wallace DC, Epstein CJ. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide-dismutase. Nat Genet 11: 376–381, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lieberthal W, Nigam SK. Acute renal failure. I. Relative importance of proximal vs. distal tubular injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F623–F631, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lieberthal W, Nigam SK. Acute renal failure. II. Experimental models of acute renal failure: imperfect but indispensable. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F1–F12, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marczin N, El Habashi N, Hoare GS, Bundy RE, Yacoub M. Antioxidants in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic potential and basic mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys 420: 222–236, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCord JM, Fridovic I. Superoxide dismutase: an enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem 244: 6049, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147: 728–741, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, George MD, Klionsky DJ, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 395: 395–398, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oku M, Sakai Y. Peroxisomes as dynamic organelles: autophagic degradation. FEBS J 277: 3289–3294, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parajuli N, Marine A, Simmons S, Saba H, Mitchell T, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T, MacMillan-Crow LA. Generation and characterization of a novel kidney-specific manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mouse. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 406–416, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paul AS, Brazil H, Gonen L. The citrate condensing enzyme of pigeon breast muscle and moth flight muscle. Acta Chem Scand 17: S129–S134, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Priault M, Salin B, Schaeffer J, Vallette FM, di Rago JP, Martinou JC. Impairing the bioenergetic status and the biogenesis of mitochondria triggers mitophagy in yeast. Cell Death Differ 12: 1613–1621, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rahman NA, Mori K, Mizukami M, Suzuki T, Takahashi N, Ohyama C. Role of peroxynitrite and recombinant human manganese superoxide dismutase in reducing ischemia-reperfusion renal tissue injury. Transplant Proc 41: 3603–3610, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rao JH, Zhang CY, Wang P, Lu L, Zhang F. All-trans retinoic acid alleviates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing manganese superoxide dismutase in rats. Biol Pharm Bull 33: 869–875, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rasbach KA, Schnellmann RG. PGC-1α over-expression promotes recovery from mitochondrial dysfunction and cell injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 355: 734–739, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rasbach KA, Schnellmann RG. Signaling of mitochondrial biogenesis following oxidant injury. J Biol Chem 282: 2355–2362, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reilly RF, Ellison DH. Mammalian distal tubule: physiology, pathophysiology, and molecular anatomy. Physiol Rev 80: 277–313, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Saba H, Batinic-Haberle I, Munusamy S, Mitchell T, Lichti C, Megyesi J, MacMillan-Crow LA. Manganese porphyrin reduces renal injury and mitochondrial damage during ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 1571–1578, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Savio M, Stivala LA, Bianchi L, Vannini V, Prosperi E. Involvement of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in DNA repair induced by alkylating agents and oxidative damage in human fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis 19: 591–596, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J 26: 1749–1760, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sengupta A, Molkentin JD, Paik JH, DePinho RA, Yutzey KE. FoxO transcription factors promote cardiomyocyte survival upon induction of oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 286: 7468–7478, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sengupta A, Molkentin JD, Yutzey KE. FoxO transcription factors promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 284: 28319–28331, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shao XL, Somlo S, Igarashi P. Epithelial-specific Cre/lox recombination in the developing kidney and genitourinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shivji MKK, Kenny MK, Wood RD. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is required for DNA excision repair. Cell 69: 367–374, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Snoeijs MGJ, van Heurn LWE, Buurman WA. Biological modulation of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 15: 190–199, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Suzuki C, Isaka Y, Takabatake Y, Tanaka H, Koike M, Shibata M, Uchiyama Y, Takahara S, Imai E. Participation of autophagy in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 368: 100–106, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suzuki K, Sawa Y, Ichikawa H, Kaneda Y, Matsuda H. Myocardial protection with endogenous overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Ann Thorac Surg 68: 1266–1271, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Suzuki K, Kirisako T, Kamada Y, Mizushima N, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. The pre-autophagosomal structure organized by concerted functions of APG genes is essential for autophagosome formation. EMBO J 20: 5971–5981, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Szeto HH, Liu S, Soong Y, Wu D, Darrah SF, Cheng FY, Zhao Z, Ganger M, Tow CY, Seshan SV. Mitochondria-targeted peptide accelerates ATP recovery and reduces ischemic kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1041–1052, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang K, Klionsky DJ. Mitochondria removal by autophagy. Autophagy 7: 297–300, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weight SC, Bell PRF, Nicholson ML. Renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Br J Surg 83: 162–170, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wredenberg A, Wibom R, Wilhelmsson H, Graff C, Wiener HH, Burden SJ, Oldfors A, Westerblad H, Larsson NGr. Increased mitochondrial mass in mitochondrial myopathy mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15066–15071, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yoboue ED, Devin A. Reactive oxygen species-mediated control of mitochondrial biogenesis. Int J Cell Biol 2012: 403870, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]