Abstract

CaMKII (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II) is a serine/threonine phosphotransferase that is capable of long-term retention of activity due to autophosphorylation at a specific threonine residue within each subunit of its oligomeric structure. The γ isoform of CaMKII is a significant regulator of vascular contractility. Here, we show that phosphorylation of CaMKII γ at Ser26, a residue located within the ATP-binding site, terminates the sustained activity of the enzyme. To test the physiological importance of phosphorylation at Ser26, we generated a phosphospecific Ser26 antibody and demonstrated an increase in Ser26 phosphorylation upon depolarization and contraction of blood vessels. To determine if the phosphorylation of Ser26 affects the kinase activity, we mutated Ser26 to alanine or aspartic acid. The S26D mutation mimicking the phosphorylated state of CaMKII causes a dramatic decrease in Thr287 autophosphorylation levels and greatly reduces the catalytic activity towards an exogenous substrate (autocamtide-3), whereas the S26A mutation has no effect. These data combined with molecular modelling indicate that a negative charge at Ser26 of CaMKII γ inhibits the catalytic activity of the enzyme towards its autophosphorylation site at Thr287 most probably by blocking ATP binding. We propose that Ser26 phosphorylation constitutes an important mechanism for switching off CaMKII activity.

Keywords: activity switch, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), CaMKII γ, phosphorylation, serine/threonine protein kinase

Abbreviations: 2D, two-dimensional; CaM, calmodulin; CaMKII, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; DTT, dithiothreitol; FBS, fetal bovine serum; LC–MS/MS, liquid chromatography tandem MS; PKA, protein kinase A; PSS, physiological saline solution; SCP3, small C-terminal domain phosphatase 3; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; wt, wild-type

INTRODUCTION

CaMKII (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II) is a ubiquitously expressed serine/threonine protein kinase, which functions as a multimeric holoenzyme consisting of 12 monomers [1,2]. The holoenzyme is organized into a ring-like structure and the catalytic/autoregulatory component of each subunit is attached to the hexameric ring by a stalk-like extension. Two such hexameric rings stacked on top of each other form the dodecameric holoenzyme. The association domain forms the core of the holoenzyme, whereas the catalytic activity resides in the peripheral ‘foot’-like structures [1,3].

Thr287 is the primary site responsible for regulation of the autonomous activity of CaMKII [4]. Activation of the kinase by Ca2+/CaM (calmodulin) causes autophosphorylation of Thr287, which generates the fully active form of CaMKII. Each monomer is phosphorylated at Thr287 by adjacent CaMKII monomers [5]. Thr287 phosphorylation results in Ca2+-independent activity of CaMKII that persists upon the removal of Ca2+. Several other autophosphorylation sites have been described for CaMKII (Ser26, Thr254, Thr262, Ser280, Thr305, Thr306, Ser319 and Ser350) ([6], but see [6a], [7–9]); however, only for some of them (Thr305, Thr306 and Thr254) are the functional consequences known [8,10,11]. The most curious of these additional sites is Ser26 due to its location in the ATP-binding site. This phosphorylation site is the main focus of the present work.

Four isoforms of CaMKII are known: α, β, γ and δ [12]. Alternative splicing of these gene products result in multiple variants [13]. The α and β isoforms have been extensively studied and are expressed primarily in neuronal tissues and brain [12,14]. They are reported to play a crucial role in behaviour and memory through their influence on LTP (long-term potentiation) at PSDs (postsynaptic densities) [15].

Unlike α and β isoforms, δ and γ isoforms are, in general, ubiquitously expressed [16]. The CAMK2D (encoding δ CaMKII) gene products have been extensively studied in cardiac muscle [15–18]. The γ isoform has been studied in the vasculature [11,19–21] and in many other tissue types [12,16,22]. The δ isoform has been linked with proliferative VSMCs (vascular smooth muscle cells), whereas the γ isoform appears to be more closely linked with non-proliferative contractile VSMCs [20,23]. Vascular tone is maintained by the contractility of differentiated VSMCs. CaMKII has been shown to be a significant regulator of vascular tone as shown by experiments with antisense knockdown of CaMKII and small molecule inhibitors [20,24].

Our group has isolated six CaMKII γ variants, C-1, C-2, G-1, G-2, B and J, from an aorta smooth muscle cDNA library [19]. The main differences between these variants occur in the segment that connects the catalytic/regulatory domain with the association domain. The C-1 and C-2 variants lack variable region 1 (V1) and variable region 2 (V2). Furthermore, C-2 lacks an eight amino acid sequence (residues 23–30) that forms part of the ATP-binding motif of the catalytic domain. Interestingly, this variant displays defective autophosphorylation at Thr287, but surprisingly is still able to phosphorylate an exogenous substrate [19]. Our laboratory has previously reported that this deleted sequence contains a serine residue (Ser26), as determined by LC–MS/MS (liquid chromatography tandem MS) of the recombinant C-1 variant, is autophosphorylated when the kinase is activated by Ca2+/CaM [7].

In the present paper, we provide evidence that phosphorylation of CaMKII γ at this novel autophosphorylation site, Ser26, occurs in vascular tissue and is important for the termination of the sustained activity of CaMKII γ.

EXPERIMENTAL

Tissue preparation

Freshly isolated aorta from the ferret was prepared as previously described [11]. Stimulated or unstimulated aorta rings were quick-frozen in 5 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) with 10% (w/v) TCA (trichloroacetic acid) in solid CO2/acetone and stored at −80°C for later use. All procedures have been approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals were maintained in a manner consistent with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were obtained and used in compliance with federal, state and local laws. Physiological experiments were performed using a PSS (physiological saline solution) as described previously [20]; 51 mM PSS with 51 mM NaCl replaced by KCl was used as depolarizing stimulus.

2D (two-dimensional) gels and immunoblotting

Samples were quick frozen in a solid CO2/acetone slurry containing DTT and TCA, and washed in acetone with 5 mM DTT. IEF (isoelectric focusing) tube gels and PAGE gels were prepared as previously described [19]. Ampholytes used were 3–10 and 5–6. Gels were transferred on to PVDF membranes and processed using a standard immunoblotting protocol. Blots were probed with a total CaMKII γ antibody, a G-2 CaMKII γ antibody and a vimentin antibody (see the Antibodies and reagents section). A two-colour LiCor Odyssey (LI-COR Biosciences) instrument was used to visualize bands quantify densitometric results. Images shown in Figures were adjusted identically for each complete dataset for better visualization (n=3–15) but this did not alter quantitative values.

Colorimetric dephosphorylation assay

A mixture centaining 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 5.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mM phosphopeptides (pSer26, pThr254, pThr262, pSer280, pThr287, pSer319 and pSer350) was used for the 500 μl reaction with or without purified SCP3 (small C-terminal domain phosphatase 3). The peptide sequences used for the experiment are as follows: pSer26, H2N-GKGAFS(p)VVRRC-COOH; pThr254, H2N-INQMLT(p)INPAK-COOH; pThr262, H2N-PAKRIT(p)ADQAL-COOH; pSer280, H2N-RSTVAS(p)MMHRQ-COOH; pThr287, H2N-MHRQET(p)VECLR-COOH; pSer319, H2N-FSAAKS(p)LLNKK-COOH; pSer350, H2N-KGSTES(p)CNTTT-COOH. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min, then 500 μl of Biomol Green reagent (see the Antibodies and reagents section) was added and the samples were incubated for another 30 min at 30°C. The extent of the reaction was calculated from the absorbance at 620 nm according to the Biomol Green reagent protocol.

Antibody generation

Polyclonal antibodies for phosphorylated Ser280 and Ser26 were generated by immunization of rabbits with the phosphopeptides CaMKII pSer280 [H2N-RSTVAS(p)MMHRQ-COOH] and CaMKII pSer26 [H2N-LGKGAFS(p)VVRRCVKKTSTQE-COOH] These peptides were synthesized as octavalent MAPs (multiple antigenic peptides) using MAP resin from EMD Chemicals. The peptides were synthesized at BBRI (Boston Biomedical Research Institute) using an Applied Biosystems Model 433A Peptide Synthesizer and Fmoc (fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl) to protect α-amino groups. Rabbits were immunized with the peptides following standard procedures at Caprologics.

Cell culture

COS-7 cells were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) culture medium supplemented with 4.5 g/l d-glucose, l-glutamine, 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate, 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% (v/v) FBS (fetal bovine serum). His-tagged CaMKII γ C-1 and mutant cDNAs in pcDNA4/HisMax TOPO vector were transfected into COS-7 cells by using Lipofectamine™ reagent (Invitrogen). The amount of Lipofectamine™ and the plasmid were titrated for the experiment according to the Lipofectamine™ protocol using OPTI-MEM to increase the transfection efficiency. Plasmids were expressed for 24 h. Cells were lysed on ice with phosphate lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 140 mM NaCl2, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P40, 1 mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor mixture and a standard immunoblotting technique was followed.

Site-directed mutagenesis

C-1 cDNA in pcDNA4/HisMax TOPO was used to mutate Ser26 to alanine (A) or aspartic acid (D) using the primers S26A-sense 5′-GCAAGGGTGCTTTCGCTGTGGTCCGCAGG-3′, S26A-antisense 5′-CCTGCGGACCACAGCGAAAGCACCCTTGC-3′, S26D-sense 5′-GGCAAGGGTGCTTTCGATGTGGTCCGCAGGTG-3′ and S26D-antisense 5′- CACCTGCGGACCACATCGAAAGCACCCTTGCC-3′. QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Mutations were confirmed later with sequencing by Eurofins MWG Operon.

Dot-blot kinase assay

A solution containing 50 mM Pipes (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.5 μg/ml CaM, 20 μM autocamtide-3 (H2N–Lys–Lys–Ala–Leu–His–Arg–Gln–Glu–Thr–Val–Asp–Ala–Leu-COOH), 0.225 mM ATP, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1× protease inhibitor and 5 μl of CaMKII was used in a 50 μl kinase-assay reaction. The reaction was stopped using 50 mM EDTA. Next, the peptide was separated from the kinase using 300 kDa cut-off spin filtration columns. Then 2 μl of the autocamtide-3 fraction of the assay were spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Dot blots were blocked and analysed with anti-total phosphothreonine antibody (see the Antibodies and reagents section). In parallel experiments under identical conditions, negative controls, consisting each of no CaM, no CaM and no ATP, and BSA only, were tested with CaMKII wt (wild-type) and resulted in no signal.

Molecular modelling

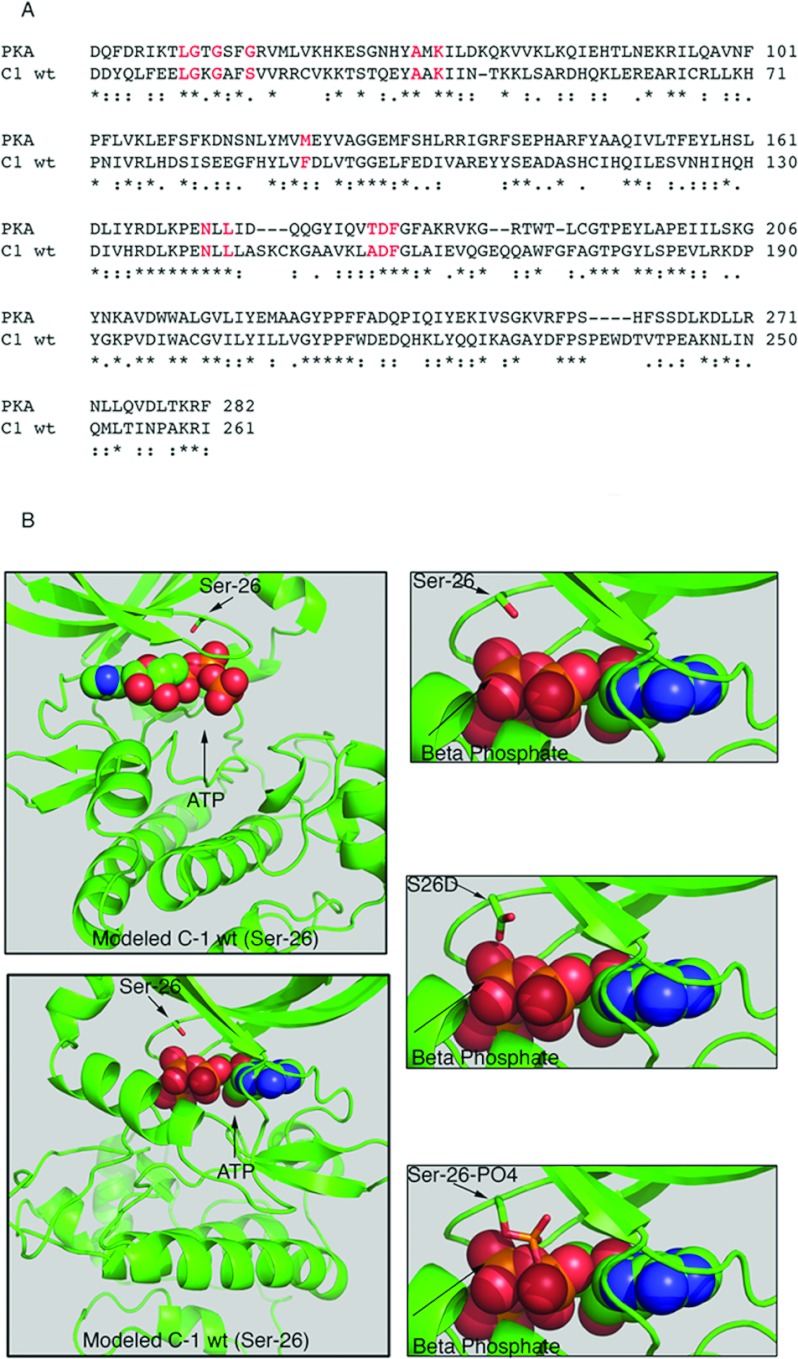

For modelling the catalytic domain of CaMKII γ C-1 isoform, we have used the Swiss Model server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) [25–27]. The model was built using the structure of PKA (protein kinase) (PDB entry 1ATP) as a template. Residues 12–261 of C-1 were aligned with residues 42–282 of PKA. Rebuilding of the missing loops was done by the Swiss Model server. Co-ordinates for ATP and two Mn2+ ions present in 1ATP were introduced into the C-1 model and the structure was optimized with Phenix [28]. Ser26 was either phosphorylated or mutated to aspartic acid using COOT [29] and the structures were energy optimized without ATP using Phenix.

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies used in present study were rabbit anti-total CaMKII γ (1:250 dilution; Upstate/Millipore); rabbit anti-CaMKII γ G-2 [21] (1:500 dilution); mouse anti-vimentin antibody (1:400 dilution; Sigma); mouse anti-tubulin (1:1000 Cell Signaling); mouse anti-His-tag antibody (1:5000 dilution; Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-phosphothreonine antibody (1:500 dilution; Cell Signaling); mouse anti-pThr287 antibody (Millipore); rabbit anti-CaMKII G-2 (1:500 dilution) [21]; fluorescently labelled secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution; LI-COR Biosciences). DMEM (Gibco), FBS (Gibco), OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen), protease inhibitor (Roche), QuikChange II XL (Stratagene), Lipofectamine™ (Invitrogen), Biomol Green reagent (Biomol International). cDNA sequences are from ferret.

Statistics

Unless indicated otherwise, significance of difference between two individual datasets was taken at P<0.05 by a two-tailed paired Student's t test. Data are presented as means±S.E.M.

RESULTS

2D gels indicate multiple post-translational modifications of CaMKII γ in vascular tissue

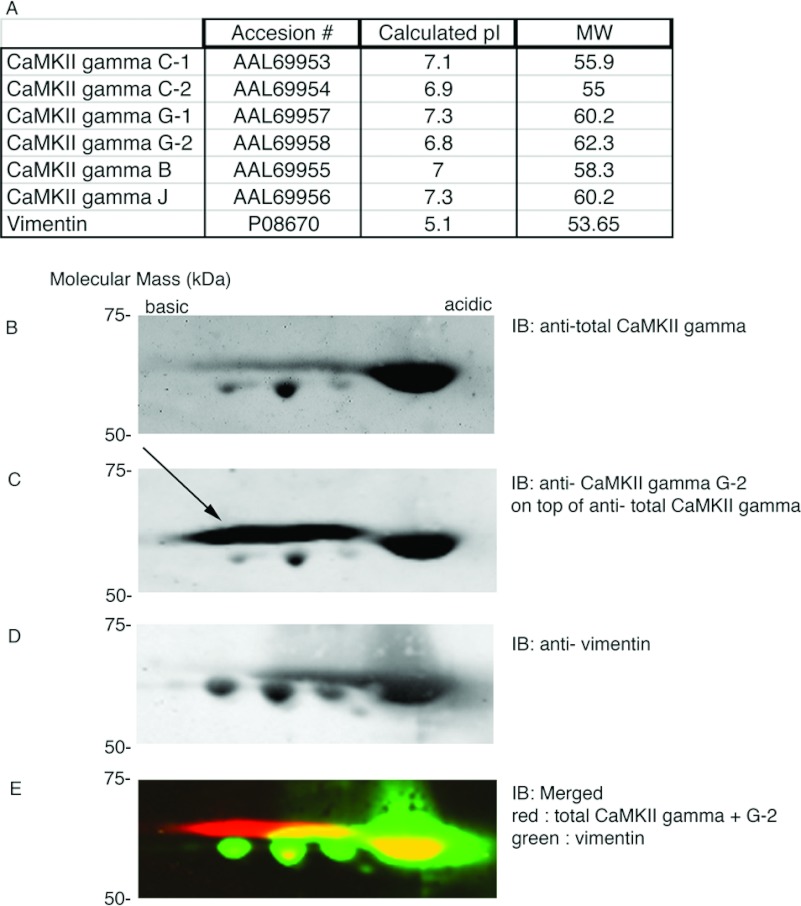

To determine whether CaMKII γ variants are phosphorylated at multiple sites in vascular tissue, we analysed vascular homogenates by 2D gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblotting, using vimentin as a reference protein. Vimentin has a calculated pI of 5.1 and post-translationally modified forms of vimentin from human arterial smooth muscle cells are known to run within the range 3.8–4.9 (Figure 1A) in 2D maps [30]. As shown in Figure 1(A), the calculated pIs of CaMKII γ variants cover the range 6.8–7.3. Figure 1(B) shows a Western blot of all CaMKII γ variants separated by 2D gel electrophoresis and stained with an anti-total CaMKII γ antibody. In addition to probing with the total CaMKII γ antibody (rabbit polyclonal, red channel), we subsequently co-labelled the blot with a CaMKII γ G-2 variant-specific antibody (also a rabbit polyclonal, red channel) to confirm the identity of CaMKII spots on the 2D gel. The CaMKII γ G-2-specific antibody typically stains an oval apparently containing several forms of the G-2 variant on the blot (Figure 1C, arrow). The same membrane was probed with an anti-vimentin antibody (monoclonal mouse, green channel) as a reference protein (Figures 1A and 1D). Figure 1(E) shows a merged image of total CaMKII and G-2 signals (red channel) and the vimentin signal (green channel). Despite their expected pI of around 7.0, CaMKII γ variants overlap with vimentin in a pI range below 5.0. Since the observed pIs for CaMKII γ variants vary from the calculated pI by roughly 2.0, these findings suggest that CaMKII variants are phosphorylated in aorta tissue. A single-site phosphorylation shifts the pI approximately 0.5 unit in the acidic direction [31]. Thus, comparison of the calculated and observed pI values suggests the presence of up to four to five phosphate groups or other post-translational modifications on CaMKII in vascular tissue.

Figure 1. Multiple post-translational modifications of CaMKII are suggested by 2D gel analysis of vascular tissue homogenates.

(A) Calculated molecular mass (Mw) and pIs of CaMKII γ variants. Vimentin (P08670) was used for comparison as a marker. (B) Representative CaMKII γ immunoblot (rabbit antibody) of a 2D gel of a whole cell homogenate of aorta tissue. (C) Subsequent probing of blot shown in (B) with a second rabbit antibody specific for the CaMKII γ G-2 variant (shown with arrow) (D) Probe of same blot for vimentin (mouse antibody) as a reference protein. (E) Merged view of CaMKII γ variants and G-2 variant (red) and vimentin (green). The brightness of the entire blot has been uniformly altered for visual display, digital values are unchanged.

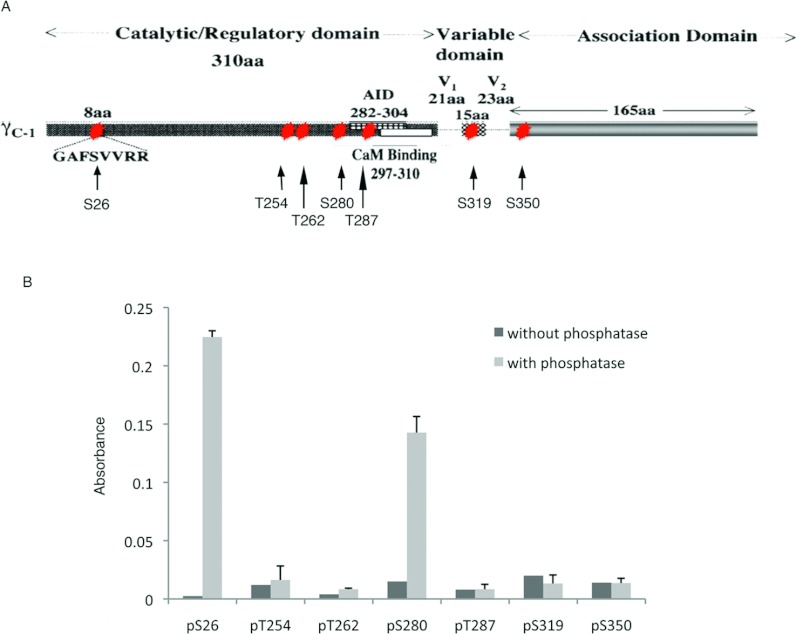

CaMKII Ser26 and Ser280 peptides are selectively dephosphorylated by SCP3

Previous in vitro analysis of autophosphorylation sites in the presence of Ca2+/CaM on recombinant CaMKII γ by LC–MS/MS of recombinant CaMKII γ identified new phosphorylation sites (Ser26, Thr262, Ser319 and Ser350) and confirmed other phosphorylation sites (Thr287, Thr254 and Ser280) [7]. We have also previously described SCP3 that binds CaMKII γ and decreases incorporated 32P, but does not dephosphorylate Thr287 [7]. However, it is not known whether any of the other identified phosphorylated site(s) are dephosphorylated by this phosphatase. Thus, we synthesized phosphopeptides containing all the previously identified [7,19] autophosphorylation sites: Ser26, Thr254, Thr262, Ser280, Thr287, Ser319 and Ser350 (Figure 2A). Dephosphorylation of these peptides by SCP3, was analysed using a colorimetric phosphate release assay. The results (Figure 2B) demonstrate selective dephosphorylation of only two sites, Ser26 and Ser280 by SCP3. In contrast, Thr254, Thr262, Thr287, Ser319 and Ser350 were not significantly dephosphorylated. Thus, these findings raise the question of whether and how the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of these sites is regulated in vivo. Thus, we focused specifically on Ser26 and Ser280.

Figure 2. Ser280 and Ser26 autophosphorylation sites are selectively dephosphorylated by SCP3.

(A) CaMKII γ C-1 domain structure. Red stars mark the residues previously shown to be autophosphorylated. aa, amino acid(s). (B) Dephosphorylation of phosphopeptides with and without SCP3 measured by a colorimetric assay for free phosphate.

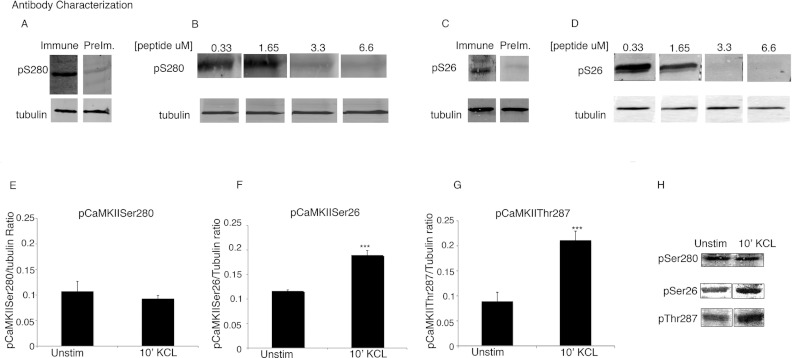

Phosphorylation of CaMKII at Ser280 is not regulated by depolarization in vascular tissue

Ser280 is located within a conserved stretch of 39 residues that constitutes the autoinhibitory and the Ca2+/CaM-binding domain in the canonical kinase fold. It is located only seven residues away from Thr287, the site responsible for the autonomous activity of CaMKII. It appears, however, to have a different function from that of Thr287 because as shown above it is dephosphorylated by SCP3, while Thr287 is not. To test if phosphorylation of Ser280 is regulated in vivo, a phosphospecific Ser280 antibody was generated using the sequence H2N-RSTVAS(p)MMHRQ-COOH. Specificity of the antibody was confirmed by comparison with preimmune serum and by probing aorta homogenate with the pCaMKIISer280-specific antibody in the presence of competing antigen (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3. Phosphorylation of Ser26 but not Ser280 is regulated by vascular tissue depolarization.

(A–D) Antibody controls, tubulin used as a loading control. (A) Whole cell aorta homogenate immunoblotted with pCaMKIISer280 immune or preimmune serum as indicated. (B) Whole cell aorta homogenate probed with pCaMKIISer280-specific antibody in the presence of increasing amounts of a competing pCaMKIISer280 peptide used as the immunogen to raise the antibody. (C) Whole cell aorta homogenate immunoblotted with pCaMKIISer26 immune or preimmune serum. (D) Whole cell aorta homogenate probed with pCaMKIISer26-specific antibody in the presence of increasing amounts of the pCaMKIISer26 peptide used as the immunogen to raise the antibody. (E) Average densitometry for pCaMKIISer280 staining of unstimulated tissue or that depolarized with 51 mM PSS. (F) Average densitometry for pCaMKIISer26 staining of unstimulated tissue or that depolarized with 51 mM PSS, P<0.01 (G) Average densitometry for pCaMKIISer287 staining of unstimulated tissue or that depolarized with 51 mM PSS. P<0.01 (H) Typical blots stained with anti-pCaMKIISer280, pCaMKIISer26 and pCaMKIIThr287 antibodies; n=3–15. The brightness of entire blot has been uniformly altered for visual display; digital values are unchanged.

Vascular tissues were quick-frozen in the presence or absence of the depolarizing stimulus (51mM KCl PSS). Depolarization is known to open voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in this tissue, raising intracellular Ca2+ levels and activating CaMKII. Tissue homogenates were probed by immunoblot with the anti-pCaMKIISer280 antibody. Mean densitometry results show no significant difference between the unstimulated and stimulated vascular samples (Figure 3E), suggesting that phosphorylation of Ser280 is not regulated under these physiological conditions.

As a positive control, a pThr287-specific antibody was used to confirm CaMKII activation in these tissues (Figure 3G).

Phosphorylation of Ser26 is regulated by depolarization in vascular tissue

Ser26 is located within a conserved stretch of nine residues (LGKGAFSVV) that constitute the upper lid of the ATP-binding site in the canonical kinase fold (bold letters indicate conserved residues). To test the physiological importance of CaMKII phosphorylation at Ser26 during vascular depolarization, a phosphospecific antibody against Ser26 was raised using the phosphopeptide sequence H2N-LGKGAFS(p)VVRRCVKKTSTQE-COOH. Antibody specificity was tested by comparing preimmune and immune serum staining of aorta homogenates. A signal at the expected molecular mass was detected only with immune serum (Figure 3C). The identity of the band was confirmed with a pCaMKIIThr287-specific antibody (results not shown). Next, the phosphopeptide used to raise the antibody was mixed with the antibody in a competition assay. As shown in Figure 3(D), the competing peptide decreased the antibody signal in a concentration-dependent manner.

Next, we tested CaMKII phosphorylation at Ser26 during vascular depolarization. The level of Ser26 phosphorylation on CaMKII was compared between unstimulated versus depolarized quick-frozen vascular tissue homogenates. As is shown in Figure 3(F), densitometric analysis of the phospho-Ser26 immuoblots normalized to tubulin co-staining shows a significant increase (~50%) with depolarization for 10 min with KCl PSS. Thus, phosphorylation of Ser26 on CaMKII is regulated during contraction in vascular tissue.

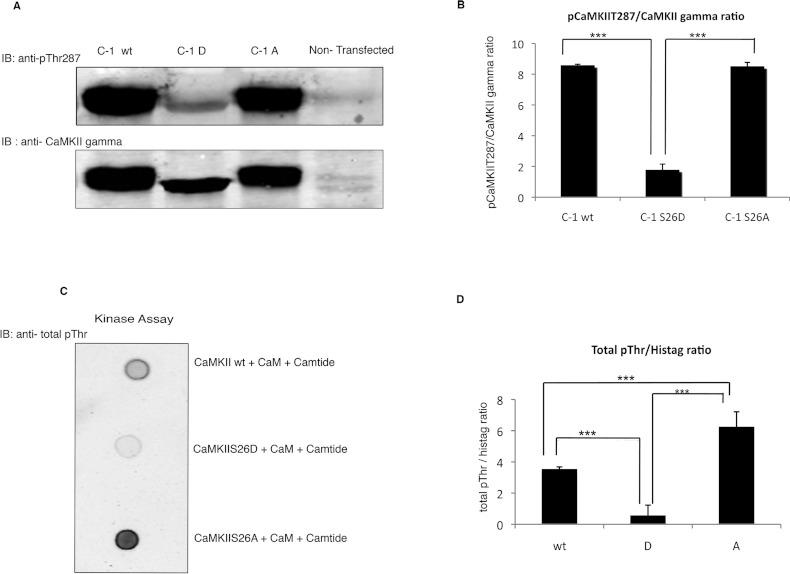

A phosphomimic S26D mutation inhibits Thr287 autophosphorylation of CaMKII

We postulated that Ser26 phosphorylation of CaMKII might alter kinase activity. To test this hypothesis, we determined the effect of mutation of Ser26 to alanine (A) or aspartic acid (D) in recombinant CaMKII. Kinase activity was assayed by monitoring Thr287 autophosphorylation. COS-7 cells were transfected with CaMKII wt, the S26D mutant or the S26A mutant. The COS-7 cell line used has no endogenous detectable CaMKII protein expression (Figure 4A). Therefore the CaMKII holoenzyme in the transfected COS-7 cells is a homo-oligomer. The Thr287 phosphorylation level was measured by probing the transfected COS-7 cell lysates in immunoblots. The results were normalized for transfection efficiency by probing co-stained immunoblots with an anti-total CaMKII γ antibody (Figure 4A). Densitometric analysis of the normalized Thr287 phosphorylation levels of the S26D and S26A mutants and wt CaMKII indicates that the level of Thr287 phosphorylation is markedly reduced in the S26D mutant (~80%) (Figure 4B). Thr287 phosphorylation of wt and S26A were not significantly different. These results indicate that phosphorylation of Ser26 inhibits Thr287 phosphorylation in the CaMKII γ homo-oligomer while the S26A mutation has no effect.

Figure 4. Phosphomimic mutation of Ser26 decreases Thr287 autophosphorylation and leads to an impaired catalytic activity toward exogenous Thr287 substrate peptide.

(A) Lysates from His-tagged C-1 wt, C-1 S26D or C-1 S26A or mock-transfected (NT) COS-7 cells probed with the indicated antibodies. (B) Densitometric quantification of the results of three similar experiments. ***P≤0.0001. (C) CaMKII wt, CaMKII S26D and CaMKII S26A recombinant proteins mixed with autocamtide-3 in a kinase activating buffer and dotted on membrane and probed for phosphothreonine. Peptide and kinase were separated using a sizing spin column and the peptide fraction used for dot blot. (D) Quantification of the results from five similar experiments. The results are normalized by the amount of kinase used in each assay. ***P≤0.001. The brightness of entire blot has been uniformly altered for visual display; digital values are unchanged.

The phosphomimic CaMKII S26D mutant cannot phosphorylate exogenous CaMKII Thr287 substrate

To investigate whether the observed inhibition of Thr287 phosphorylation in the S26D mutant is due to a direct inhibition of kinase activity, an in vitro kinase assay was performed using a 13-amino-acid peptide containing Thr287 (autocamtide-3) as a substrate. His-tagged purified recombinant CaMKII wt, the S26D mutant and the S26A mutant were used in vitro dot-blot kinase assays containing 20 μM autocamtide-3, 5 μg/ml CaM and 10 mM CaCl2 to activate the kinase. The phosphorylated peptide was separated from the holoenzyme (~680 kDa) using a sizing spin column. As shown in Figure 4(C) and is quantified in Figure 4(D), the S26D mutant caused negligible threonine phosphorylation of the exogenous peptide even though significant amounts of peptide phosphorylation were seen with the S26A mutant and wt kinase. The S26A mutant showed significantly more activity in phosphorylating the substrate peptide than did wt kinase, suggesting that autophosphorylation of the wt kinase leads to less than the maximal possible kinase activity.

Taken together, these results indicate that the negative charge on Ser26 of CaMKII γ introduced by the mutation or by autophosphorylation of wt kinase inhibits the catalytic activity of the enzyme towards its autophosphorylation site at Thr287.

Structural interpretation of the CaMKII inhibition by Ser26 phosphorylation

In the absence of a three-dimensional structure of CaMKII phosphorylated on Ser26 we used homology modelling to explain a plausible mechanism for the kinase inhibition by Ser26 phosphorylation or S26D mutation. Ser26 is located in a stretch of residues that form the first two β-strands and the connecting loop of the β domain in the canonical kinase fold. We refer to this segment as the ‘upper lid’ of the ATP-binding site because these residues make extensive interactions with the ATP molecule, specifically with the triphosphate moiety, as observed, for example, in the structure of the PKA–ATP complex [32]. Glycine is the most commonly found amino acid at the position corresponding to CaMKII Ser26. This semi-conserved glycine residue plays an important role in positioning the triphosphate moiety for catalysis by making a strong hydrogen bond with one of the β-phosphate oxygen atoms. Besides the serine residue found in all CaMKII isoforms there are also alanine and histidine found among the very few substitutions at this position in the kinase superfamily. Thus, there must be a strong evolutionary selection at this position and it is probable that the glycine→ serine substitution plays an important function specific for CaMKII. To evaluate the possible consequences of introducing an acidic group at this position, we have modelled the wt CaMKII γ C-1 isoform, its phosphorylated form and the S26D mutant based on the structure of PKA (PDB entry 1ATP). We found the PKA structure to be a better template for the modelling than the recently published structure of CaMKII γ isoform (PDB entry 1V7O), because in the latter the loop containing Ser26 is disordered due to the absence of the triphosphate moiety in the bound inhibitor. In the modelled structure of C-1, all the interactions between the protein and ATP are well preserved including a correct geometry and bond lengths for the bound metal (Mn2+), which positions the γ phosphate for catalysis. Therefore we are confident that our model has all the essential features of the CaMKII structure. The modelled structures suggest that the negatively charged side chain carboxy group of the aspartic acid residue or the phosphate attached to the serine side chain oxygen would clash with the β-phosphate group of ATP, thus either sterically interfering with the catalysis, i.e. with the transfer of the γ phosphate to a substrate such as Thr287 or inhibiting the ATP binding (Figure 5). Furthermore, owing to the orientation of the Ser26 side chain towards the catalytic cleft, and its position close to the β-phosphate of the bound ATP, this side chain is not readily accessible to an external kinase molecule. It appears that the phosphorylation of Ser26 most probably occurs by an intramolecular mechanism. We propose that phosphorylation of Ser26 works as an internal break that allows the switching off the constitutively active oligomeric CaMKII.

Figure 5. Atomic model depicting a role for Ser26 phosphorylation.

(A) Alignment with the protein whose structure was used for modelling and marking the residues that were used for structural homology alignment residues involved in ATP binding are shown in red (B) On the left, the front and the back view (rotated 180° on the y-axis) of the modelled C-1 wt structure with ATP. On the right, close view of atomic structure of unphosphorylated Ser26, S26D and phosphorylated Ser26 (Ser26-PO4) on modelled CaMKII C-1 structure with ATP. Atomic colour code: Phosphate (orange), oxygen (red), carbon (green), nitrogen (blue). Structures drawn using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger.

DISCUSSION

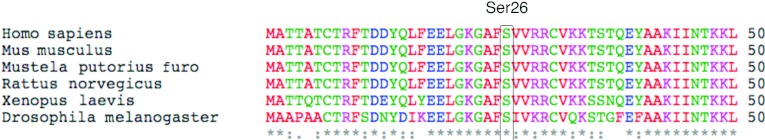

CaMKII Ser26 is conserved in all CaMKII isoforms from mammals through to Drosophila, but not in yeast (Figure 6). This points to an important functional role for the site. Additionally, Ser26 is known to be part of the ATP-binding motif of the catalytic domain [33] as shown in Figure 5(A). In the current study, we have demonstrated, first, that Ser26 in CaMKII γ is regulated by phosphorylation during depolarizing stimuli in blood vessels and, secondly, by mutagenesis that phosphorylation at this site switches off Ca2+-activated kinase activity, preventing prolonged kinase activity.

Figure 6. Conservation of Ser26 across species.

Homo sapiens CaMKII γ isoform 1 (NP_751911.1), Mus musculus CaMKII γ isoform 1 (NP_848712.2), Mustela putorius furo (AAL69953.1), Rattus norvegicus CaMKII γ (NP_598289.1), Xenopus laevis CaMKII γ M (AAG17558.1), Drosophila melanogaster CaMKII isoform B (AAF59390.2)

Ser26 is located within a conserved stretch of nine residues (LGKGAFSVV) that constitutes the upper lid of the ATP-binding site in the canonical kinase fold. The phosphomimic mutation of CaMKII (S26D) causes a dramatic decrease in Thr287 phosphorylation levels, while the S26A mutation has no effect. The decreased Thr287 autophosphorylation in the oligomer could be due to a number of possible mechanisms. To directly test the possibility that the Ser26 phosphomimic impairs the activity of the catalytic cleft, we used an exogenous substrate known as autocamtide-3, and found, indeed that the phosphomimic kinase (S26D) has an impaired catalytic activity.

One interesting issue that arises is that, when whole vascular tissue homogenates are probed in immunoblots for phosphorylation of CaMKII Thr287 and Ser26 phosphorylation (Figure 3) phosphorylation of both sites appears to coexist during steady-state depolarization of the tissue. This is in marked contrast with the results with the phosphomimic mutants in recombinant homo-oligomers (Figure 4). Tissue-wide depolarization of cells leads to a non-selective Ca2+ rise in stimulated VSMCs, which is expected to globally activate a large pool of CaMKII. Global activation of a promiscuous kinase is unlikely to be advantageous to the cell and would be expected to disrupt targeting of specific signalling pathways. Thus, Ser26 phosphorylation might be a mechanism controlling the spatially distributed CaMKII activity during a rapid Ca2+ flux into the VSMCs.

CaMKII in which either Ser26 or Thr287 is phosphorylated may occur in different cellular pools. This concept is consistent with what we know about the targeting of the G-2 variant of CaMKII γ in smooth muscle and its interaction with SCP3. SCP3 is a small PP2C (protein phophatase 2C)-type C-terminal domain phosphatase present in vascular smooth muscle. CaMKII γ G-2 and SCP3 are co-localized on a central vimentin- and α actinin-containing cytoskeleton in unstimulated VSMCs; however, once the cell is depolarized G-2 and SCP3 separate and G-2 is targeted to the cell surface [21]. SCP3 is of interest since it decreases total 32P incorporation into CaMKII by autophosphorylation but does not dephosphorylate Thr287 [7]. We now show that it dephosphorylates Ser26 and Ser280 preferentially, with no activity towards other sites including Thr287 (Figure 3). Thus, when CaMKII and SCP3 co-localize, SCP3 would keep Ser26 dephosphorylated but when they separate, Ser26 would be phosphorylated by the still active kinase and would then inhibit kinase activity, producing a ‘sleeping’ pool of CaMKII at the cell surface.

We have previously reported that the B and J variants of the CaMKII γ isoform ‘autodephosphorylate’ [19]. Others have described a similar phenomenon and attributed it to a reverse of the activation mechanism [34], but this mechanism did not fully explain our observations. The effect of Ser26 phosphorylation to inhibit kinase activity could well explain these previous observations as well. Thus, if Thr287 phosphorylation is a mechanism for ‘remembering’ phosphorylation [35], then Ser26 phosphorylation may be a mechanism for ‘forgetting’.

Taken together, we demonstrate here that there are novel autophosphorylations in vitro and in vivo on CaMKII, and Ser26 is one of them. We have discovered that a Ser26 phosphomimic CaMKII has impaired Thr287 phosphorylation and reduced catalytic activity, probably due to inhibition of ATP binding. This action constitutes an important mechanism for switching the kinase off, possibly in a spatially targeted manner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Susanne Vetterkind (Boston University, Boston, MA, U.S.A.) for valuable scientific input and Cynthia Gallant (Boston University, Boston, MA, U.S.A.) for excellent technical support. We also thank F. Timur Senguen (BBRI, Watertown, MA, U.S.A.) for his help with molecular graphics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Mehtap Yilmaz, Kathleen Morgan and Samudra Gangopadhyay conceived and designed the experiments; Mehtap Yilmaz and Samudra Gangopadhyay performed the experiments; Paul Leavis designed and synthesized the peptides; Mehtap Yilmaz and Zenon Grabarek modelled the three-dimensional protein structure; Mehtap Yilmaz prepared the Figures and drafted the paper; Mehtap Yilmaz, Kathleen Morgan and Zenon Grabarek analysed the data, interpreted the results and revised and edited the paper before acceptance.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers HL031704 (to K.G.M.), HL091162 (to Z.G.)].

References

- 1.Hudmon A., Schulman H. Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 2002;364:593–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rellos P., Pike A. C., Niesen F. H., Salah E., Lee W. H., von Delft F., Knapp S. Structure of the CaMKII delta/calmodulin complex reveals the molecular mechanism of CaMKII kinase activation. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudmon A., Schulman H. Neuronal calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: the role of structure and autoregulation in cellular function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:473–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patton B. L., Miller S. G., Kennedy M. B. Activation of type-II calcium calmodulin-dependent protein-kinase by Ca2+ calmodulin is inhibited by sutophosphorylation of threonine within the calmodulin-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:11204–11212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson P. I., Meyer T., Stryer L., Schulman H. Dual role of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of multifunctional CaM kinase may underlie decoding of calcium signals. Neuron. 1994;12:943–956. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao L. H., Stratton M. M., Lee I. H., Rosenberg O. S., Levitz J., Mandell D. J., Kortemme T., Groves J. T., Schulman H., Kuriyan J. A mechanism for tunable autoinhibition in the structure of a human Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II holoenzyme. Cell. 2011;146:732–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Erratum. Cell. 147:704. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gangopadhyay S. S., Gallant C., Sundberg E. J., Lane W. S., Morgan K. G. Regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II by a small C-terminal domain phosphatase. Biochem. J. 2008;412:507–516. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Migues P. V., Lehmann I. T., Fluechter L., Cammarota M., Gurd J. W., Sim A. T., Dickson P. W, Rostas J. A. P. Phosphorylation of CAMKII at Thr253 occurs in vivo and enhances binding to isolated post synaptic densities. J. Neurochem. 2006;98:289–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vosseller K., Hansen K. C., Chalkley R. J., Trinidad J. C., Wells L., Hart G. W., Burlingame A. L. Quantitative analysis of both protein expression and serine/threonine post-translational modifications through stable isotope labeling with dithiothreitol. Proteomics. 2005;5:388–398. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elgersma Y., Fedorov N. B., Ikonen S., Choi E. S., Elgersma M., Carvalho O. M., Giese K. P., Silva A. J. Inhibitory autophosphorylation of CaMKII controls PSD association, plasticity, and learning. Neuron. 2002;36:493–505. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munevar S., Gangopadhyay S. S., Gallant C., Colombo B., Sellke F. W., Morgan K. G. CaMKII T287 and T305 regulate history-dependent increases in α agonist-induced vascular tone. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008;12:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobimatsu T., Fujisawa H. Tissue-specific expression of four types of rat calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II messenger RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:17907–17912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tombes R. M., Krystal G. W. Identification of novel human tumor cell-specific CaMKII variants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1355:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(96)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takaishi T., Saito N., Tanaka C. Evidence for distinct neuronal localization of gamma and delta subunits of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II in the rat-brain. J. Neurochem. 1992;58:1971–1974. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tombes R. M., Faison M. O., Turbeville J. M. Organization and evolution of multifunctional Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase genes. Gene. 2003;322:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayer K. U., Löhler J., Schulman H., Harbers K. Developmental expression of the CaM kinase II isoforms: ubiquitous gamma- and delta-CaMKII are the early isoforms and most abundant in the developing nervous system. Mol. Brain Res. 1999;70:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo T., Zhang T., Ginsburg K. S., Mishra S., Brown J. H., Bers D. M. CaMKIIδC slows [Ca]i decline in cardiac myocytes by promoting Ca sparks. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2461–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra S., Ling H., Grimm M., Zhang T., Bers D. M., Brown J. H. Cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure development through Gq and CaMKII signaling. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2010;56:598–603. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e1d263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gangopadhyay S. S., Barber A. L., Gallant C., Grabarek Z., Smith J. L., Morgan KG. Differential functional properties of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma variants isolated from smooth muscle. Biochem. J. 2003;372:347–357. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim I., Je H. D., Gallant C., Zhan Q., Riper D. V., Badwey J. A., Singer H. A., Morgan K. G. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent activation of contractility in ferret aorta. J. Physiol. 2000;526:367–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marganski W. A., Gangopadhyay S. S., Je H. D., Gallant C., Morgan K. G. Targeting of a novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is essential for extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated signaling in differentiated smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2005;97:541–549. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182630.29093.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrino B. A. Regulation of gastrointestinal motility by Ca2+/calmodulin-stimulated protein kinase II. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;510:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.House S. J., Singer H. A. CaMKII-δ isoform regulation of neointima formation after vascular injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:441–447. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rokolya A., Singer H. A. Inhibition of CaM kinase II activation and force maintenance by KN-93 in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C537–C545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. The Swiss-Model workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guex N., Peitsch M. C. Swiss-Model and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., Peitsch MC. Swiss-Model: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. Phenix: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupont A., Corseaux D., Dekeyzer O., Drobecq H., Guihot A. L., Susen S., Vincentelli A., Amouyel P., Jude B., Pinet F. The proteome and secretome of human arterial smooth muscle cells. Proteomics. 2005;5:585–596. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowles E. A., Agrwal N., Anderson R. L., Wang J. L. Carbohydrate-binding protein 35 isoelectric points of the polypeptide and a phosphorylated derivative. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:17706–17712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng J. H., Trafny E. A., Knighton D. R., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Ten Eyck L. F., Sowadski J. M. 2.2-Å refined crystal-structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein-kinase complexed with MnATP and a peptide inhibitor. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1993;49:362–365. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanks S. K., Hunter T. Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 1995;9:576–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byrne M. J., Putkey J. A., Waxham M. N., Kubota Y. Dissecting cooperative calmodulin binding to CaM kinase II: a detailed stochastic model. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2009;27:621–638. doi: 10.1007/s10827-009-0173-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fink C. C., Meyer T. Molecular mechanisms of CaMKII activation in neuronal plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002;12:293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]