Abstract

Cardiotonic steroids (CTS) of the strophanthus and digitalis families have opposing effects on long-term blood pressure (BP). This implies hitherto unrecognized divergent signaling pathways for these CTS. Prolonged ouabain treatment upregulates Ca2+ entry via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-1 (NCX1) and TRPC6 gene-encoded receptor-operated channels in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) in vivo and in vitro. Here, we test the effects of digoxin on Ca2+ entry and signaling in ASMC. In contrast to ouabain treatment, the in vivo administration of digoxin (30 μg·kg−1·day−1 for 3 wk) did not raise BP and had no effect on resting cytolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) or phenylephrine-induced Ca2+ signals in isolated ASMCs. Expression of transporters in the α2 Na+ pump-NCX1-TRPC6 Ca2+ signaling pathway was not altered in arteries from digoxin-treated rats. Upregulated α2 Na+ pumps and a phosphorylated form of the c-SRC protein kinase (pY419-Src, ∼4.5-fold) were observed in ASMCs from rats treated with ouabain but not digoxin. Moreover, in primary cultured ASMCs from normal rats, treatment with digoxin (100 nM, 72 h) did not upregulate NCX1 and TRPC6 but blocked the ouabain-induced upregulation of these transporters. Pretreatment of ASMCs with the c-Src inhibitor PP2 (1 μM; 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine) but not its inactive analog eliminated the effect of ouabain on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression and ATP-induced Ca2+ entry. Thus, in contrast to ouabain, the interaction of digoxin with α2 Na+ pumps is unable to activate c-Src phosphorylation and upregulate the downstream NCX1-TRPC6 Ca2+ signaling pathway in ASMCs. The inability of digoxin to upregulate c-Src may underlie its inability to raise long-term BP.

Keywords: cardiotonic steroids, Na+ pumps, NCX1, TRPC proteins, receptor-operated Ca2+ entry

cardiotonic steroids (CTS) have a long history in the treatment of heart failure and certain cardiac arrhythmias (3). Besides their role in regulation of cardiac function, endogenous CTS that are structurally related to the strophanthus family and that include ouabain are also implicated in control of salt metabolism and blood pressure (BP) (11, 49). Plasma levels of endogenous ouabain are significantly elevated in ∼45% of patients with essential hypertension (48, 55) and in animals with several forms of salt-dependent hypertension (16, 21, 26). Moreover, in rodents, the prolonged administration of low doses of ouabain induces ouabain-induced hypertension (OH) (29, 30, 39, 40, 46, 61).

Endogenous ouabain influences arterial tone and peripheral vascular resistance (10, 12, 20) by activating Ca2+ signaling pathways in arterial smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) (46). These “signature” pathways involve inhibition of high-affinity α2 Na+ pumps and increased Ca2+ entry via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-1 (NCX1), and TRPC gene-encoded receptor- and store-operated channels (ROCs and SOCs, respectively) (46). Rodent ASMCs express α2 Na+ pumps that mostly modulate Ca2+ homeostasis and Ca2+ signaling (18). Prior work has shown that the expression of α2 Na+ pumps, NCX1 and TRPC1 and TRPC6 is upregulated in ASMCs from OH rats (46). These transporters are involved in control of agonist-mediated vasoconstriction (51, 63), myogenic tone, and BP (25, 57, 62, 63). The arterial expression of NCX1 and TRPC6 is augmented in Milan hypertensive rats (64) and TRPC6 is upregulated in mineralocorticoid-salt hypertensive rats (4); both hypertension models are characterized by elevated plasma levels of endogenous ouabain (16, 21).

In contrast to ouabain, digoxin, which is also a specific Na+ pump inhibitor with high affinity for α2 in rodents (42), does not raise BP in normal rats (39). Moreover, digoxin is an effective antihypertensive in the OH rat (24, 29, 39), and Digitalis preparations have antihypertensive actions in some patients with essential hypertension (1). As the opposing effects of these CTS on long-term BP are not explained by differences in their ability to inhibit α2 Na+ pumps, the hypertensinogenic action of ouabain involves binding to α2 Na+ pumps (14, 15, 37) followed by the specific triggering of a co-related signaling event.

The Na+ pump also acts as a hormone receptor that can transduce the binding of circulating CTS into activation of intracellular protein kinases and Ca2+ signaling (32, 35). Ouabain binding to Na+ pumps activates the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, c-Src, and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, including extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) (32). Members of the Src-kinase family can phosphorylate/regulate TRPC channels (22, 27, 54), while MAPKs regulate expression of NCX1 (59). Here, we tested the hypothesis that the opposing long-term effects of ouabain and digoxin on BP can be explained by their effects on arterial smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling.

METHODS

Ethical approval.

All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines of and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Ouabain- and digoxin-treated rats.

Male 7- to 8-wk-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Frederick, MD) were maintained in an air-conditioned, temperature (23°C)-controlled facility with a 12:12-h light/dark cycle. Rats had free access to tap water and were fed standard rat chow (containing 0.5% wt/wt sodium and 1.1% wt/wt potassium) ad libitum. Body weight was measured weekly. Rats were allowed to acclimatize to the facility and the procedures of BP measurements for 1 wk preceding actual data collection. The rats were randomized to three groups to receive ouabain, digoxin (both 30 μg·kg−1·day−1 in phosphate-buffered saline), or vehicle given subcutaneously, via Alzet model 2004 mini osmotic pumps (39). Systolic and mean BPs were recorded weekly by tail-cuff plethysmography using a commercial photoelectric system (model 29 Blood Pressure Meter/Amplifier; IITC, Woodland Hill, CA) and a device providing constant rates of cuff inflation and deflation. The average values for BP in each rat were obtained typically from five sequential cuff inflation-deflation cycles (46). Systolic (SBP) and mean (MBP) blood pressures were obtained by direct inspection of the recordings. Diastolic BPs were calculated from the standard blood pressure equation: DBP = (3MBP − SBP)/2.

Dissection of arteries for immunoblotting.

The superior mesenteric artery and aorta from euthanized rats were rapidly excised and placed in ice-cold Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS). The arteries were cleaned of fat and connective tissue, de-endothelialized, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before protein extraction, as described (8).

Freshly dissociated ASMCs for Ca2+ imaging.

Myocytes were isolated from rat mesenteric arteries, as described (8). The superior mesenteric artery was cleaned of fat and connective tissue, and digested in low-Ca2+ (0.05 mM) physiological salt solution (PSS) containing 2 mg/ml collagenase type XI, 0.16 mg/ml elastase type IV, and 2 mg/ml bovine serum album (BSA, fat free) for 35 min at 37°C. The PSS contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 5 NaHCO3, 1.4 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 11.5 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). After digestion, the tissue was washed three times with low-Ca2+ PSS at 4°C. A suspension of single cells was obtained by gently triturating the tissue with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette in low-Ca2+ PSS. Smooth muscle cells were differentiated by their characteristic elongated morphology. Dispersed cells were directly deposited on glass coverslips for fluorescence microscopy. ASMCs on coverslips were stored at 4°C and used within 4 h. Cells, on coverslips, were loaded with fura-2 by incubating them in PSS containing 3.3 μM fura-2-AM for 35 min at 20–22°C, with 5% CO2-95% air (8). Freshly dissociated cells that were markedly contracted under resting conditions (more than 5%) were excluded. Cells were studied for 40–60 min during continuous superfusion with PSS. At the conclusion of Ca2+ imaging experiments, the same cells were labeled for smooth muscle α-actin to identify the ASMCs (17).

Primary cultured ASMCs for Ca2+ imaging and Western blot analysis.

Primary cultured ASMCs were prepared from the rat superior mesenteric artery (17). Briefly, the superior mesenteric artery was isolated under sterile conditions from euthanized male 9- to 10-wk-old Sprague-Dawley rats, as described above. The cleaned, de-endothelialized artery was incubated for ∼45 min at 37°C in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free HBSS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase, type 2. After the incubation, the adventitia was carefully stripped, the endothelium was removed, and segments of the muscle layer were stored overnight in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) at 37°C (17). The next morning, ASMCs in the remaining smooth muscle were dissociated by digestion for 35–40 min at 37°C in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free HBSS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase, type 2, and 0.5 mg/ml elastase, type IV. The dissociated cells were resuspended and plated on either 25-mm coverslips for use in fluorescent microscopy experiments or on 10-cm culture dishes for Western blot analysis. The plated cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air at 37°C. The medium was changed on days 4 and 7. In cultures in which the effects of ouabain and/or digoxin were tested, the standard growth medium was replaced by serum-free growth medium 24 h before the CTS were added. Experiments were performed on subconfluent cultures on days 8–9 in vitro if not indicated otherwise. The purity of ASMC cultures was verified by positive staining with smooth muscle-specific α-actin (17). Most of the cells (>99.5%) were α-actin positive.

Calcium imaging.

The cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]cyt, was measured with fura-2 by using digital imaging (8). Primary cultured ASMCs were loaded with fura-2 by incubation for 35 min in culture medium containing 3.3 μM fura-2-AM (20–22°C, 5% CO2-95% air). After dye loading, the coverslips were transferred to a tissue chamber mounted on a microscope stage, where cells were superfused for 15–20 min (35–36°C) with PSS to wash away extracellular dye. Cells were studied for 40–60 min during continuous superfusion with PSS (35°C).

The imaging system was designed around a Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The dye-loaded cells were illuminated with a diffraction grating-based system (Polychrome V, TILL Photonics, Germany). Fluorescent images were recorded using a CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Image acquisition and analysis were performed with a MetaFluor/MetaMorph Imaging System (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). [Ca2+]cyt was calculated from the ratio of fura-2 fluorescent emission (510 nm) with excitation at 380 and 360 nm (the isosbestic point), as described (8). Intracellular fura-2 was calibrated in situ in freshly dissociated and in primary cultured ASMCs (8). Intracellular Ba2+ measurements are shown as fura-2 340/380 excitation ratios with fluorescent emission at 510 nm (8).

Immunobloting.

Cultured ASMCs were harvested in PBS supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets and were pelleted (3,000 g, 4°C, 20 min). The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing (in mM) 145 NaCl, 10 NaH2PO4, 10 NaN3, and 1% IGEPAL supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets. The suspension was centrifuged (5,000 g, 4°C, 30 min). The supernate containing the extracted proteins was mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (8). Similar immunoblot analysis was performed on proteins extracted from the frozen arteries (8). Typically, superior mesenteric arteries from two to four rats were pooled and pulverized with a stainless steel mortar and pestle. Membrane proteins were solubilized in SDS buffer, and separated by SDS-PAGE as described (8). The following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-TRPC6 (dilution 1:200) (Allomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel); mouse monoclonal anti-NCX1 (dilution 1:500) (R3F1; Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland); rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+ pump α1-subunit isoform (dilution 1:2,000) (gift of Dr. Thomas Pressley); rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+ pump α2-subunit isoform (dilution 1:750) (Millipore, Billerica, MA); rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Src family (Tyr418) (dilution 1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Src (dilution 1:1000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Gel loading was controlled with monoclonal anti-β-actin antibodies (dilution 1:10,000) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or monoclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody (dilution 1:5,000) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). After being washed, membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG for 1 h at room temperature. The immune complexes on the membranes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence-plus (Amersham BioSciences, Piscataway, NJ) and exposure to X-ray film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Quantitative analysis of immunoblots was performed by using a Kodak DC120 digital camera and 1D Image Analysis Software (Eastman Kodak).

Materials.

FBS was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). All other tissue culture reagents were obtained from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, NY). Fura 2-AM and DAPI were obtained from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen Detection Technologies, Eugene, OR). 1-Oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), PP2 and PP3 (4-amino-7-phenylpyrazol[3,4-d]pyrimidine) were purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Collagenase (type 2) was obtained from Worthington Biochemical (Freehold, NJ). Ouabain, digoxin, dimethylsulfoxide, smooth muscle α-actin, collagenase (type XI), elastase (type IV), BSA, nifedipine, phenylephrine, penicillin G, and streptomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets were obtained from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). All other reagents were analytic grade or the highest purity available.

Statistical analysis.

The numerical data presented in results are means ± SE from n single cells (1 value per cell). Immunoblots were repeated at least four to six times for each protein. The number of animals is presented where appropriate. Data from 6–18 rats were obtained for most protocols. Statistical significance was determined using Student's paired or unpaired t-test, or two-way ANOVA, as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Comparison of chronic in vivo effects of digoxin and ouabain on BP and ASMC Ca2+ signaling ex vivo.

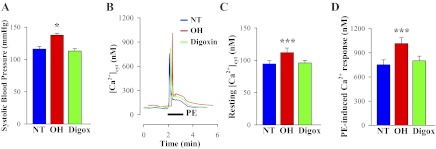

As shown in Fig. 1A, sustained hypertension was induced by the prolonged administration of ouabain but not digoxin. By the second week of the treatments, systolic BP increased only in the ouabain-infused group and remained elevated until the rats were euthanized at week 3 (137 ± 3 mmHg vs. vehicle 116 ± 4 mmHg, P < 0.05). Systolic BP in digoxin-treated (“digoxin”) rats was not significantly altered (113 ± 4 mmHg; P > 0.05). Diastolic BP was 91 ± 2, 86 ± 2, and 88 ± 2 mmHg, respectively, in ouabain-, digoxin-, and vehicle-treated rats (P < 0.05 ouabain treated vs. digoxin treated). Previous work using the same infusion protocol has shown that the plasma ouabain and digoxin levels are raised substantially in the CTS-infused groups, typically reaching 3–5 nM (39). These levels are well above the level of endogenous CTS, i.e., endogenous ouabain ∼0.5 nM and digoxin-like immunoreactivity <0.08 nM in the control rats (39).

Fig. 1.

Blood pressure and calcium homeostasis in mesenteric artery myocytes from control normotensive (NT), ouabain-hypertensive (OH), and digoxin-treated (Digox) rats. A: systolic blood pressure in control (NT), OH and digoxin-treated rats. Normal male rats were infused with either vehicle (control), ouabain (30 μg·kg−1·day−1), or digoxin (30 μg·kg−1·day−1) for 3 wk. Representative groups of rats (n = 9 each) are shown. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated rats (ANOVA). B: phenylephrine (PE)-induced Ca2+ transients in freshly dissociated arterial smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) from control (NT), OH, and “digoxin” rats. Representative records show the time course of cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) changes induced by 1 μM PE. C and D: summarized data showing resting [Ca2+]cyt (C; 112 control, 99 OH and 102 “digoxin” cells) and peak PE-induced Ca2+ transient (D; 57 control, 52 OH and 53 “digoxin” cells) in ASMCs from 9 control, 9 OH, and 9 digoxin-treated rats. ***P < 0.001 vs. ASMCs from control rats.

Confirming a prior observation, the prolonged administration of ouabain induced significantly higher resting [Ca2+]cyt and phenylephrine (PE)-induced Ca2+ responses in freshly dissociated mesenteric artery myocytes vs. those from control rats (46). However, in contrast to ouabain, the prolonged administration of digoxin did not affect resting [Ca2+]cyt or PE-induced Ca2+ signals (Fig. 1, B–D). Accordingly, in all subsequent experiments with digoxin, ouabain was used in parallel as a positive control. Both the peak initial Ca2+ response, believed to be the result of inositol trisphosphate (InsP3)-mediated SR Ca2+ release, and the later sustained Ca2+ signal, mediated by Ca2+ entry through ROCs and/or SOCs, were not altered in ASMCs from digoxin-treated rats (Fig. 1, B–D). Superimposed records of the PE-induced Ca2+ response show that the integral of the rise of [Ca2+]cyt (area under the [Ca2+]cyt curve) in OH arterial myocytes was increased to 131 ± 4% of the area in the control (vehicle) ASMCs (n = 28 control cells; n = 36 OH cells, P < 0.05). The area under the [Ca2+]cyt curve in arterial myocytes from digoxin-treated rats was not significantly altered (103 ± 3%; P > 0.05).

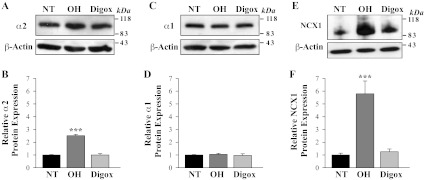

Comparison of chronic in vivo digoxin and ouabain on ASMC α2 Na+ pumps and NCX1.

Altered Ca2+ signaling in freshly dissociated mesenteric artery myocytes from OH rats is associated with upregulated expression of α2 Na+ pumps, NCX1 and TRPC1 and TRPC6. Moreover, α2 Na+ pumps and NCX1 mediate the effects of low-dose ouabain on smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling and vasoconstriction (15, 25, 62). However, as shown in Fig. 2, A and B, the expression of α2 Na+ pumps was not altered in mesenteric arteries from digoxin-treated rats in contrast to the ∼2,5-fold α2 Na+ pump upregulation in arteries from ouabain-treated rats. Further, the expression of α1 Na+ pumps, which have very low affinity for ouabain (43) and digoxin (42) in rodents, was not altered in arteries from ouabain- or digoxin-treated rats (Fig. 2, C and D). In addition, expression of NCX1 also was not altered in arteries from digoxin-treated rats (Fig. 2, E and F), while it was markedly upregulated (∼5–6-fold) in ouabain-treated rats (46).

Fig. 2.

Expression of Na+ pump α1- and α2-subunit isoforms and NCX1 in arterial myocytes from control NT, OH, and digoxin-treated rats. Western blot analysis of Na+ pump α2 (A, B), α1 subunits (C, D), and NCX1 (E, F) protein expression in smooth muscle cell membranes from mesenteric arteries of control (NT), OH rats, and digoxin-treated (Digox) rats. A, C, and E show representative blots. All lanes were loaded with 30 μg of membrane protein. Summary data (B, D, and F) are normalized to the amount of β-actin and are expressed as means ± SE from 4 (B), 4 (D), and 6 (F) immunoblots (total of 18 rats). ***P < 0.001 vs. ASMCs from control NT rats.

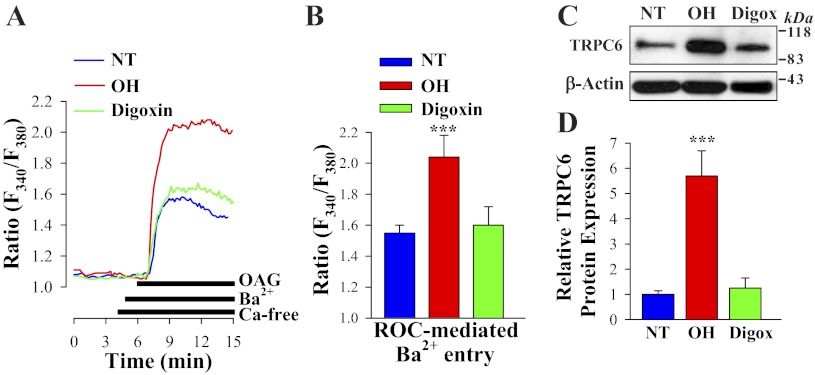

Effect of chronic in vivo digoxin and ouabain on ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry and TRPC6 expression in ASMC.

To determine whether ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry contributes to differential PE-induced Ca2+ responses in arterial myocytes from “digoxin” and ouabain-treated rats (Fig. 1, B and D), freshly dissociated ASMCs were stimulated with the cell-permeable diacylglycerol (DAG) analog OAG. OAG opens TRPC3 and TRPC6 channels in a protein kinase C-independent manner (23). Ba2+ was used as the charge carrier because SOCs have high Ca2+ selectivity and, unlike ROCs, are virtually impermeable to other alkaline-earth cations, such as Ba2+. Further, Ba2+ is not transported by SERCA or PM Ca2+ pumps (31). In the presence of extracellular Ba2+, 80 μM OAG induced significantly larger elevations of cytosolic Ba2+ (fura-2 340/380 nm ratio) in myocytes from OH rats than in those from digoxin-treated or control rats (Fig. 3, A and B). To eliminate the contribution of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to OAG-induced Ba2+ entry, all solutions contained 10 μM nifedipine (46). The differential effects of in vivo administration of these CTS on ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry were associated with significant (∼6-fold) upregulation of TRPC6 in deendothelialized mesenteric artery from OH but not from digoxin rats (Fig. 3, C and D). TRPC6 is an obligatory component of endogenous ROCs in a variety of cell types including vascular myocytes (23, 46). Expression of TRPC3 was not significantly affected in ASMCs from ouabain- (46) or digoxin-treated rats (not shown). The expression of TRPC1 and TRPC5, which are believed to form subunits of SOCs (7), was not altered in ASMCs from digoxin-treated rats (not shown), but expression of TRPC1 was upregulated in mesenteric arteries from ouabain-treated rats (46). TRPC4 is not expressed in rat mesenteric arteries (8). The results show that digoxin, in contrast to ouabain, is unable to upregulate the α2-NCX1-TRPC6 (ROC) signaling pathway.

Fig. 3.

1-Oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG)-induced [receptor-operated channel (ROC)-mediated] Ba2+ entry and TRPC6 protein expression in freshly dissociated ASMCs from control NT, OH, and digoxin-treated rats. A: representative records show the time course of the Fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) signals induced by 80 μM OAG in freshly dissociated ASMCs from control, OH, and digoxin-treated rats. Extracellular Ca2+ was replaced by 1 mM Ba2+ during the period indicated on the graph. Nifedipine (10 μM) was applied 10 min before the trace shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. B: summarized data show the OAG-induced, ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry in 28 control, 22 OH, and 25 digoxin-treated rat mesenteric ASMCs. Each bar corresponds to data from 6 rats. C and D. Western blot analysis of TRPC6 expression in ASMCs from control (NT), OH, and digoxin-treated (Digox) rats. C: representative immunoblot (30 μg protein/lane). D: summarized data from 8 immunoblots (total of 18 rats) are normalized to β-actin. ***P < 0.001 vs. control ASMCs.

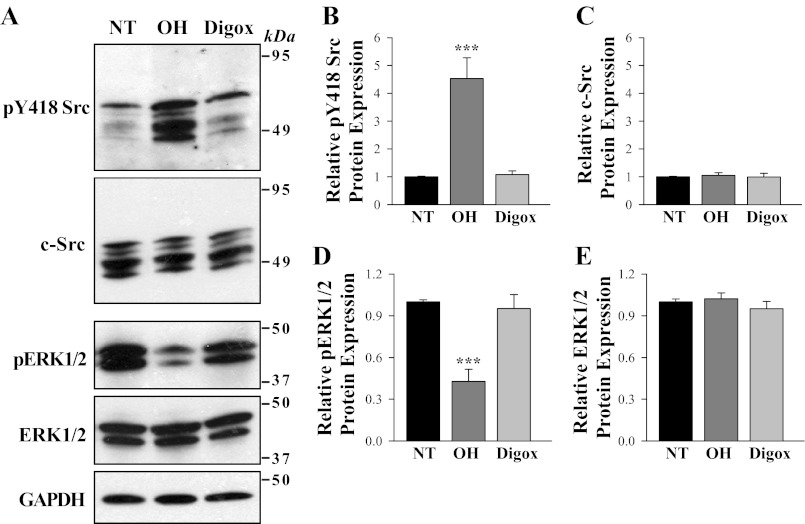

Differential regulation of phosphorylated Src and ERK1/2 in ASMCs from digoxin- and ouabain-treated rats.

Binding of ouabain to Na+ pumps activates c-Src and stimulates various pathways including ERK1/2 and members of the MAP kinase family of serine/threonine kinases (32). Src and MAP kinase families play a key role in ASMC signaling events (44) and regulation of arteriolar contractility (53). The chronic in vivo administration of ouabain and digoxin had different effects on arterial expression and phosphorylation of endogenous c-Src and ERK1/2 (Fig. 4, A–E). In these studies, activation of c-Src was assessed with an anti-phospho-Src antibody that detects c-Src phosphorylation/activation at Tyr-418 (pY418-Src). As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, pY418-Src was upregulated ∼4- to 5-fold in mesenteric arteries from ouabain- but not digoxin-treated rats. The antibody detected multiple bands between 49 and 60 kDa, consistent with the presence of multiple Src family members in ASMCs (2). All bands were greatly increased in the ouabain-treated group. In contrast, the phosphorylated form of ERK1/2 was downregulated (by ∼2-fold) in ouabain- but not digoxin-treated rats (Fig. 4, A and D). Expression of constitutive c-Src and ERK1/2 was not altered by any treatment (Fig. 4, A, C, E).

Fig. 4.

Effects of in vivo ouabain and digoxin administration on phosphorylation of arterial smooth muscle Src and ERK1/2. A: Western blot analysis of expression and phosphorylation of Src (pY-418 Src) and ERK1/2 in deendothelialized mesenteric arteries from control (NT), OH, and digoxin-treated rats. Representative blot is shown (30 μg protein/lane). B–E: summarized data were normalized to the amount of GAPDH and are expressed as means ± SE from 4 (B), 4 (C), 4 (D), and 4 (E) immunoblots (total of 12 rats). ***P < 0.001 vs. ASMCs from control NT rats.

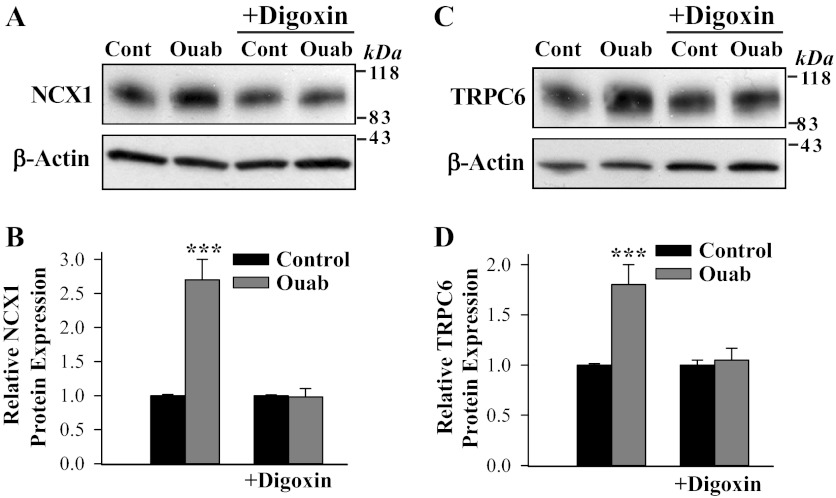

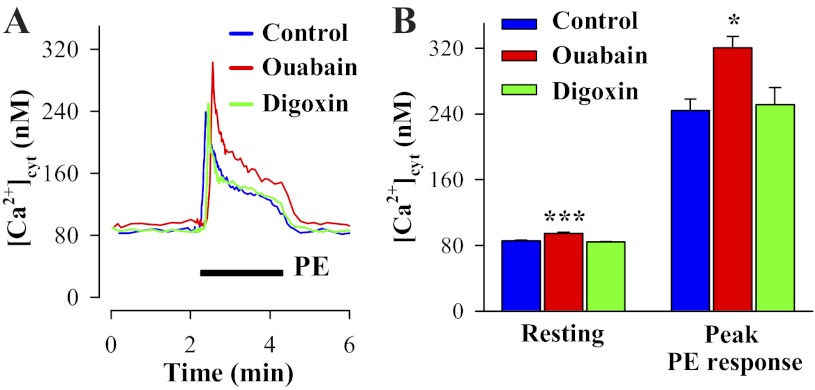

In vitro replication of the actions of in vivo ouabain and digoxin.

As shown in Fig. 5, treatment of cultured ASMCs from normal rats with ouabain for 72 h enhanced NCX1 and TRPC6 protein expression and Ca2+ signaling. Parallel digoxin treatment of primary cultured rat mesenteric artery myocytes had no effect on the expression of these transporters. However, digoxin completely blocked the stimulatory effect of ouabain on NCX1 (Fig. 5, A and B) and TRPC6 expression (Fig. 5, C and D). The ouabain-evoked changes in NCX1 and TRPC6 expression were reflected in elevated resting [Ca2+]cyt and augmented PE-induced Ca2+ responses, whereas digoxin was inactive (Fig. 6). Similar results (not shown) were obtained with ATP-evoked responses; treatment with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h increased ATP-induced Ca2+ responses (905 ± 77 vs. 582 ± 84 nM in control untreated ASMCs; n = 49, P < 0.05). Thus the lack of effects of in vivo digoxin administration on arterial Ca2+ signaling observed in Fig. 1, B–D, is confirmed ex vivo with cultured ASMCs. Superimposed records of the PE-induced Ca2+ response show that the integral of the rise of [Ca2+]cyt (area under the [Ca2+]cyt curve) in ouabain-treated ASMCs was increased to 138 ± 3% of the area in control untreated ASMCs (n = 39 control ASMCs; n = 43 ouabain-treated ASMCs, P < 0.05). The area under the [Ca2+]cyt curve in the digoxin-treated ASMCs was not altered (101 ± 2%; n = 49 cells, P > 0.05). Thus the in vitro effects of prolonged ouabain or digoxin treatment on arterial myocytes mimic the in vivo changes.

Fig. 5.

Digoxin blocks the effect of ouabain on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression in cultured rat mesenteric artery myocytes. A–D: Western blot analysis of NCX1 and TRPC6 expression in control (Cont) untreated myocytes (1st lane in A and C) and ASMCs treated for 72 h with 100 nM digoxin (3rd lane in A and C) and with 100 nM ouabain (Ouab) in the absence (2nd lane in A and C) and presence of 100 nM digoxin (4th lane in A and C). A and C: representative immunoblots (30 μg protein/lane). Summarized data from 7 (B) and 6 (D) immunoblots were normalized to β-actin. ***P < 0.001 vs. control ASMCs.

Fig. 6.

Effects of prolonged incubation with nanomolar ouabain or digoxin on Ca2+ signaling in primary cultured rat ASMCs. A: PE-induced Ca2+ responses in control mesenteric artery myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain or digoxin for 72 h. Nifedipine (10 μM) was added 10 min before the records shown and was maintained throughout the experiments. B: summarized data showing resting [Ca2+]cyt and peak PE-induced Ca2+ response in control myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain or 100 nM digoxin for 72 h. Resting [Ca2+]cyt data are from 316 control myocytes, 290 ouabain-treated, and 288 digoxin-treated ASMCs. PE-induced Ca2+ responses were studied in 43 control myocytes, 39 ouabain-treated, and 49 digoxin-treated ASMCs. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control ASMCs.

Involvement of Src kinases as a determinant of ouabain- and digoxin-induced responses in primary cultured rat ASMCs.

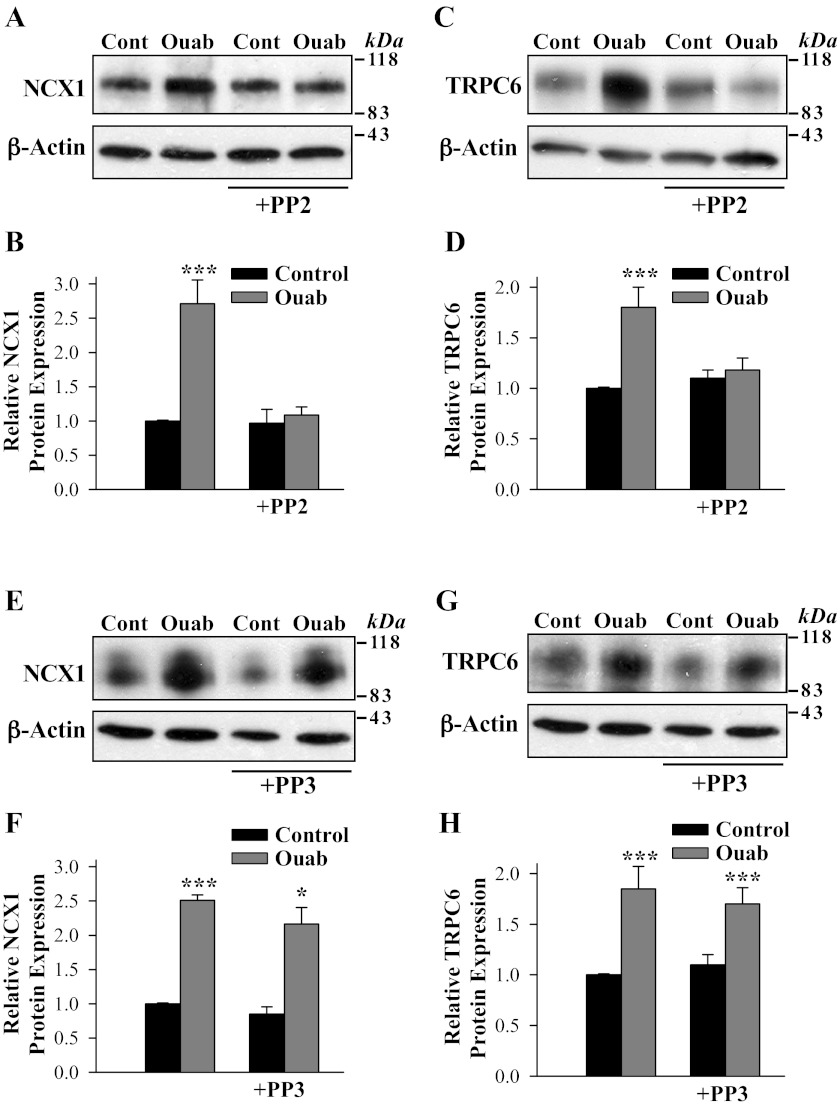

Pretreatment of ASMCs with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM) blocked the ability of ouabain to upregulate NCX1 and TRPC6 expression (Fig. 7, A–D); pretreatment of ASMCs with PP3 (1 μM), an inactive analog of PP2, did not prevent the ouabain-induced upregulation of either NCX1 (Fig. 7, E and F) or TRPC6 (Fig. 7, G and H).

Fig. 7.

PP2, a Src inhibitor, eliminates the effect of ouabain treatment on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression in cultured rat ASMCs. A–D: NCX1 and TRPC6 protein expression in control (untreated) myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain (72 h) in the absence and presence of 1 μM PP2. E–H: PP3 (1 μM) did not prevent the upregulating effect of ouabain (100 nM, 72 h) on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression in cultured rat ASMCs. A, C, E, and G show representative blots. All lanes were loaded with 30 μg of membrane protein. Summary data (B, D, F, and H) are normalized to the amount of β-actin and are expressed as means ± SE from 8 (B), 7 (D), 4 (F), and 4 (H) immunoblots. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control ASMCs.

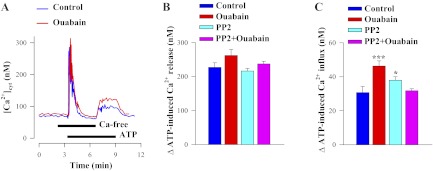

The ouabain-evoked changes in Ca2+ transporter expression were also reflected in altered Ca2+ handling following PP2 pretreatment. Figure 8A illustrates the protocol: it shows the time course of ATP-induced changes in [Ca2+]cyt in the absence and presence of extracellular Ca2+ in control and ouabain-treated ASMC. Ouabain treatment increased ATP-induced SR Ca2+ release (the initial rise in [Ca2+]cyt in Fig. 8A) only marginally (Fig. 8B) but augmented the secondary rise in Ca2+ (∼55%) associated with Ca2+ entry via SOCs and ROCs (Fig. 8, A and C). Exposure of cultured control ASMCs to 1 μM PP2 for 72 h did not affect the ATP-induced Ca2+ release but modestly increased extracellular Ca2+ entry (Fig. 8, B and C). However, PP2 treatment eliminated the effect of ouabain on Ca2+ influx (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

PP2 blocks the effect of 100 nM ouabain treatment (72 h) on ATP-evoked (SOC/ROC-mediated) Ca2+ entry in cultured rat ASMCs. A: representative records showing the time course of [Ca2+]cyt changes induced by 10 μM ATP in Ca2+-free and Ca2+-containing solutions in control untreated ASMC (blue line) and arterial myocytes treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h (red line). Nifedipine (10 μM) was added 10 min before the records shown and was maintained throughout the experiments. B, C: summarized data showing the mean peak amplitudes ± SE of ATP-induced Ca2+ release (B) and Ca2+ influx (C), measured from the basal (“resting”) [Ca2+]cyt (Δ[Ca2+]cyt in nM); blue bars = control ASMCs, red bars = ouabain-treated ASMCs, cyan bars = PP2-treated ASMCs, and magenta bars = PP2 + ouabain-treated ASMCs. Ca2+ release data are from 89 control myocytes, 107 ouabain-treated, 151 PP2-treated, and 159 PP2+ouabain-treated ASMCs. ATP-induced Ca2+ influx was studied in 90 control myocytes, 62 ouabain-treated, 153 PP2-treated, and 156 PP2 + ouabain-treated ASMCs. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control ASMCs.

DISCUSSION

The present report describes the first study of some key mechanisms involved in the differential regulation of arterial myocyte Ca2+ signaling, and consequently BP, by two CTS, ouabain and digoxin. The major new results are as follows. 1) The ability of ouabain to upregulate NCX1, TRPC6, and Ca2+ signaling in arterial myocytes depends critically upon the activation of c-Src. 2) Conversely, the inability of the structurally related and commonly used CTS, digoxin, to upregulate Ca2+ transporter expression and augment Ca2+ signaling is explained by its failure to activate c-Src. 3) Digoxin is not without impact in this system. Although inactive as an agonist, digoxin behaves as a receptor antagonist of ouabain binding to the Na+ pump. By blocking the ability of ouabain to bind and thus activate c-Src, digoxin prevents the upregulation of Ca2+ transporter expression and signaling in arterial myocytes. 4) The differential signaling evoked by two different ligands acting within a common receptor indicates that, like many seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), the α2 Na+ pump isoform in ASMCs exhibits a profound functional ligand bias.

Overall, the results provide the first explanation for, and are highly consistent with, the view that the hypertensive effect of ouabain in vivo involves activation of α2 Na+ pump-Src kinase signaling and that this event is critical for the subsequent upregulation of Ca2+ entry mediated by NCX1 and TRPC6 (ROC). These findings also provide the first molecular explanation for the paradoxical antihypertensive effects of digoxin in salt-sensitive and ouabain hypertensive rats (24, 39), and the antihypertensive effect of digitalis preparations in some hypertensive patients (1).

Digoxin and ouabain differentially regulate Ca2+ homeostasis in rat ASMCs.

There is accumulating evidence that endogenous Na+ pump inhibitors play an important role in cardiovascular, renal, and other disorders (5). Among the endogenous CTS, endogenous ouabain is elevated in a large portion of patients with never-treated essential hypertension (38). Moreover, prolonged ouabain infusions, that generally replicate the elevated plasma levels observed in patients, induce hypertension (30, 39, 40, 46, 61). However, patients with heart failure have long been treated with digitalis preparations (58) without the side effect of hypertension. If hypertension is not a recognized side-effect of digitalis treatment, why would ouabain raise BP when all the classic CTS are well-documented Na+ pump inhibitors (6, 60)? Further, ouabain and digoxin have comparable binding affinity for rodent α2 (KD of 0.26 and 0.15 μM, respectively) (42). Indeed, in rodents, both ouabain and digoxin, when acutely applied in nanomolar doses, increase the vascular tone of resistance arteries (9, 34, 47, 62). In humans also, both digoxin (41) and ouabain (50) share a short-term vasopressor action. Moreover, in humans digoxin augments pressor responses to norepinephrine and angiotensin (19).

While the acute vascular effects of ouabain and digoxin appear to be generally indistinguishable in humans and rodents, and consistent with the classical view of their mechanism of action, there has been no explanation for the ability of prolonged infusions of ouabain to induce hypertension in rodents. Similarly, the absence of long-term pressor activity with digoxin is also an enigma (24, 29, 39). The present results are thus of relevance as they show that ouabain and digoxin have very different effects on ASMC Ca2+ signaling that are mediated by specific Na+ and Ca2+ transport proteins (Figs. 1–3). Indeed, the ability of ouabain to upregulate Na+ pump α2-subunits, NCX1 and TRPC6 proteins in the ASMCs from ouabain-infused rats stands in stark contrast to the lack of any observed effect in the digoxin-treated rats. The first component in the signaling pathway affected by ouabain is the high ouabain affinity α2 Na+ pump. The CTS binding site is critical for the hypertensinogenic activity of ouabain; mutation of the α2 binding site to a CTS resistant form prevents ouabain- and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-induced hypertension (14, 15, 37).

Of critical relevance, digoxin is unable to replicate the effects of ouabain on Ca2+ signaling not only in vivo but also in vitro. This obviates uncertainties associated with differences in whole body volume of distribution, clearance, and metabolism as an explanation for their disparate signaling effects in excised arteries. Exposure of isolated ASMC to nanomolar digoxin also had no effect on NCX1 and TRPC6 protein expression in marked contrast to ouabain (Fig. 5). Digoxin, however, was able to block the upregulation of these transporters by ouabain. Thus the prolonged interaction of ouabain, but not digoxin, with α2 Na+ pumps is necessary to drive up NCX1 and TRPC6 protein expression and Ca2+ signaling. As NCX1 operates primarily in the Ca2+ entry mode in ASMCs of arteries with tone (25, 63), Ca2+ entry is likely to be augmented in all rodent hypertension models characterized by elevated plasma levels of endogenous ouabain (64).

Prior work has shown that the expression of NCX1 and TRPC6 (and ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry) are interrelated; experiments with silencer RNA support the view that NCX1 lies upstream of TRPC6 in the α2-NCX1-TRPC6 (ROC) signaling pathway (46). The upregulation of TRPC6 is thought to further accelerate Ca2+ entry. Consistent with this view, ATP-induced Ca2+ entry, likely mediated by ROCs and SOCs (46), was augmented in ouabain-treated cells (Fig. 8). The resting [Ca2+]cyt level and PE-evoked Ca2+ responses were also increased by prolonged ouabain, but not digoxin treatment in vivo and in vitro (Figs. 1, B and C, and Fig. 6). The aforementioned observations indicate that the upregulation of the Na+ and Ca2+ transporters and Ca2+ signaling in ouabain-treated rats is triggered and maintained by ouabain and is not secondary to elevated BP.

Elimination of the ouabain effects on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression by digoxin normalized Ca2+ entry and arterial tone. Indeed, digoxin (Fig. 1A) and digitoxin do not induce hypertension in rats and, moreover, reverse ouabain-dependent hypertension (39). The remarkable differences in the long-term effects of these two Na+ pump inhibitors suggest that their common receptor, the α2 Na+ pump, exhibits “biased” functional selectivity (28). In such a system, ligand binding evokes a series of signals, some common to all ligands (i.e., inhibition of Na+ pumps by CTS) and other signals that are sensitive to specific structural features of the ligand (e.g., ouabain-evoked Ca2+ signaling). One of the best documented examples of ligand biased functional responses are the seven transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors which generate different intracellular signals that depend upon discrete and often small structural variations in the ligand (13). To our knowledge, the present results are the first molecular evidence indicating that the Na+ pump behaves in a manner analogous to GPCRs in this regard. The functional basis for the ligand bias is that Na+ pump-bound ouabain and digoxin likely interact with multiple amino acid residues in the binding site, while only certain interactions unique to bound ouabain trigger c-Src activation. In this regard, the spatial configuration of the binding site residues and hence ligand interaction is likely modified by long range interaction with intracellular binding partners. Detailed information on the identity of Na+ pump binding partners, and especially those that might trigger activation of Src, is not available in ASMCs. Further, the binding partners may vary among different cell types so that the signaling effects of ouabain and digoxin may be similar in some systems and not others and may even be α-isoform-specific. For example, both ouabain and digoxin, when acutely applied at high doses, activated c-Src and inhibited protein synthesis in human cancer cell lines (56). Thus no evidence for biased CTS receptors (likely α1 Na+ pumps) was observed in that study.

c-Src mediates the differential action of ouabain and digoxin on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression and Ca2+ signaling in rat ASMCs.

A key observation in this study is that pY418-Src is upregulated in mesenteric arteries from ouabain- but not digoxin-treated rats (Fig. 4, A and B) and that pretreatment with the c-Src inhibitor PP2 prevents ouabain from upregulating NCX1 and TRPC6 (Fig. 7, A–D) and ATP-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 8C). These results show that the ouabain-induced enhancement of NCX1 and TRPC6 expression reflects prior ouabain/Na+ pump mediated Src activation, i.e., c-Src is a key upstream regulator of the Na+ and Ca2+ transporters and Ca2+ signaling in ASMCs. Furthermore, the aforementioned data show that c-Src can be activated by chronic in vivo ouabain treatment at concentrations as low as ∼3 nM (Fig. 4, A and B), overlapping the plasma level of ouabain in infused rats (39). The potent effects of ouabain on c-Src phosphorylation indicates this in vivo effect is mediated by the ouabain-binding α2, but not the α1 catalytic subunit because the latter is ouabain-insensitive in rodents.

In many cell types, ouabain activates c-Src, induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor, and activates the Ras/ERK1/2 cascade (32, 49). Surprisingly, we did not observe activation of ERK1/2 in mesenteric arteries from OH rats, although c-Src was upregulated (Fig. 4, A, B, and D). In contrast, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was downregulated in OH rats and was unaffected in arteries from digoxin-treated rats (Fig. 4, A and D). The lack of ERK1/2 activation in OH rats may be explained, in part, by specificity in the α isoforms that affect the degree of Na+ pump-mediated signaling to ERK1/2 (45). Indeed, Pierre and colleagues (45) demonstrated that α2, in contrast to other α subunits, does not support the ouabain-dependent ERK1/2 activation. The downregulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in OH rats (Fig. 4, A and D) occurs through a pathway(s) which remains to be determined.

Once bound to Na+ pumps, the steps that link ouabain with c-Src activation and that trigger upregulation of the NCX1-TRPC6 (ROC) signaling pathway remain unclear. Studies of the high ouabain affinity α1 Na+ pumps (33) of pig renal epithelial cells (32, 52) had suggested that ouabain-induced signaling results from a direct interaction of the α1 subunit with Src protein kinases. Other recent work indicates that the ability of ouabain to activate c-Src is not mediated via direct contact between the kinase and Na+ pump subunits (36).

Src kinases can interact with TRPC channels and are involved in their regulation (22, 27, 54). For instance, Src phosphorylates TRPC3 at Y226 and formation of phospho-Y226 is essential for TRPC3 activation (27). Tyrosine phosphorylation by Src family protein-tyrosine kinases also regulates TRPC6 channel activity (22). Furthermore, TRPC6 activation by a receptor-tyrosine kinase-PLCγ pathway (triggered by epidermal growth factor) is inhibited by PP2 (22). Acute application of PP2 or genistein (a general tyrosine kinase inhibitor) also blocks Ca2+ entry via TRPC3 gene-encoded ROCs (27, 54). In this general context, it is not surprising that inhibition of c-Src activation prevents ouabain-induced upregulation of TRPC6 (Fig. 7, C and D) and eliminates effect of ouabain on the ATP-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 8C). However, the exact relevance of the c-Src-TRPC6 interaction in the present context is not clear; we have previously shown that even in the presence of ouabain, the evoked upregulation of TRPC6 is absent when NCX1 upregulation is prevented (46). Under such conditions, c-Src should be active. Thus the cSrc-TRPC6 interaction may be important for channel activity, but by itself it is not sufficient to upregulate TRPC6 expression in these cells.

Finally, in view of all the aforementioned results, it seems unlikely that the different effects of ouabain and digoxin are associated with their ability to cross cell membranes. Like digoxin, ouabagenin (another Strophanthus steroid) crosses the plasma membranes fairly readily but retains the marked hypertensive activity of ouabain (39).

In summary, our results show that c-Src activation is a critical point of divergence that underlies the differential effects of ouabain and digoxin on the NCX1/TRPC6 Ca2+ signaling pathway in ASMCs. These findings represent further molecular evidence that ouabain-like prohypertensinogenic CTS have hormone-like signaling activity while other commonly used CTS that bind tightly to the same biased Na+ pump α2 subunit receptors not only lack this ability, but can act as antagonists with powerful BP lowering effects.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-PO1-078870 Project 2 (V. A. Golovina), HL-045215 (J. M. Hamlyn), and by funds from the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.Z., C.I.L., M.V.P., S.G.B., I.P., and J.M.H. performed experiments; A.Z., C.I.L., M.V.P., S.G.B., I.P., and V.A.G. analyzed data; A.Z., C.I.L., M.V.P., S.G.B., and V.A.G. interpreted results of experiments; A.Z., C.I.L., M.V.P., S.G.B., and V.A.G. prepared figures; A.Z., C.I.L., M.V.P., S.G.B., I.P., J.M.H., and V.A.G. approved final version of manuscript; C.I.L., J.M.H., and V.A.G. edited and revised manuscript; V.A.G. conception and design of research; V.A.G. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Thomas A. Pressley (Texas Tech Univ.) for the generous gift of anti-α1 Na+ pump antibodies and Dr. Mordecai P. Blaustein for comments on the manuscript.

Present address of A. Zulian: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Padova, Padova, Italy.

Present address of M. V. Pulina: Developmental Biology Program, Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY 10065.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abarquez RF., Jr Digitalis in the treatment of hypertension. A preliminary report. Acta Med Philipp 3: 161–170, 1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abram CL, Courtneidge SA. Src family tyrosine kinases and growth factor signaling. Exp Cell Res 254: 1–13, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Love TE, Lloyd-Jones DM, Aban IB, Colucci WS, Adams KF, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the DIG trial. Eur Heart J 27: 178–186, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae YM, Kim A, Lee YJ, Lim W, Noh YH, Kim EJ, Kim J, Kim TK, Park SW, Kim B, Cho SI, Kim DK, Ho WK. Enhancement of receptor-operated cation current and TRPC6 expression in arterial smooth muscle cells of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 25: 809–817, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagrov AY, Shapiro JI, Fedorova OV. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: physiology, pharmacology, and novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev 61: 9–38, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balzan S, D'Urso G, Ghione S, Martinelli A, Montali U. Selective inhibition of human erythrocyte Na+/K+ ATPase by cardiac glycosides and by a mammalian digitalis like factor. Life Sci 67: 1921–1928, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beech DJ, Muraki K, Flemming R. Non-selective cationic channels of smooth muscle and the mammalian homologues of Drosophila TRP. J Physiol 559: 685–706, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berra-Romani R, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Pulina MV, Golovina VA. Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C779–C790, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaustein MP. How does ouabain, but not digoxin, elevate blood pressure? New insight from studies of ouabain-digoxin interactions in arteries. Proceedings of the Joint Research Conference of the Institute for Advanced Studies and the Israel Science Foundation on Na+,K+-ATPase, Jerusalem, Israel (Abstract), 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaustein MP. Sodium ions, calcium ions, blood pressure regulation, and hypertension: a reassessment and a hypothesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 232: C165–C173, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaustein MP, Leenen FH, Chen L, Golovina VA, Hamlyn JM, Pallone TL, Van Huysse JW, Zhang J, Wier WG. How NaCl raises blood pressure: A new paradigm for the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1031–H1049, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaustein MP, Zhang J, Chen L, Song H, Raina H, Kinsey SP, Izuka M, Iwamoto T, Kotlikoff MI, Lingrel JB, Philipson KD, Wier WG, Hamlyn JM. The pump, the exchanger, and endogenous ouabain: signaling mechanisms that link salt retention to hypertension. Hypertension 53: 291–298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeWire SM, Violin JD. Biased ligands for better cardiovascular drugs: dissecting G-protein-coupled receptor pharmacology. Circ Res 109: 205–216, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dostanic-Larson I, Van Huysse JW, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. The highly conserved cardiac glycoside binding site of Na,K-ATPase plays a role in blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15845–15850, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dostanic I, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Theriault S, Van Huysse JW, Lingrel JB. The alpha2-isoform of Na-K-ATPase mediates ouabain-induced hypertension in mice and increased vascular contractility in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H477–H485, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrandi M, Manunta P, Balzan S, Hamlyn JM, Bianchi G, Ferrari P. Ouabain-like factor quantification in mammalian tissues and plasma: comparison of two independent assays. Hypertension 30: 886–896, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Preparation of primary cultured mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells for fluorescent imaging and physiological studies. Nat Protoc 1: 2681- 2687, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golovina VA, Song H, James PF, Lingrel JB, Blaustein MP. Na+ pump alpha2-subunit expression modulates Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C475–C486, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guthrie GP., Jr Effects of digoxin on responsiveness to the pressor actions of angiotensin and norepinephrine in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 58: 76–80, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddy FJ, Overbeck HW. The role of humoral agents in volume expanded hypertension. Life Sci 19: 935–947, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Bova S, DuCharme DW, Harris DW, Mandel F, Mathews WR, Ludens JH. Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 6259–6263, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hisatsune C, Kuroda Y, Nakamura K, Inoue T, Nakamura T, Michikawa T, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K. Regulation of TRPC6 channel activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 279: 18887–18894, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397: 259–263, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang BS, Kudlac M, Kumarathasan R, Leenen FH. Digoxin prevents ouabain and high salt intake-induced hypertension in rats with sinoaortic denervation. Hypertension 34: 733–738, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwamoto T, Kita S, Zhang J, Blaustein MP, Arai Y, Yoshida S, Wakimoto K, Komuro I, Katsuragi T. Salt-sensitive hypertension is triggered by Ca2+ entry via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type-1 in vascular smooth muscle. Nat Med 10: 1193–1199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaide J, Ura N, Torii T, Nakagawa M, Takada T, Shimamoto K. Effects of digoxin-specific antibody Fab fragment (Digibind) on blood pressure and renal water-sodium metabolism in 5/6 reduced renal mass hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 12: 611–619, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki BT, Liao Y, Birnbaumer L. Role of Src in C3 transient receptor potential channel function and evidence for a heterogeneous makeup of receptor- and store-operated Ca2+ entry channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 335–340, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336: 296–302, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura K, Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Different effects of in vivo ouabain and digoxin on renal artery function and blood pressure in the rat. Hypertens Res 23, Suppl: S67–S76, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurashina T, Kirchner KA, Granger JP, Patel AR. Chronic sodium potassium-ATPase inhibition with ouabain impairs renal haemodynamics and pressure natriuresis in the rat. Clin Sci (Lond) 91: 497–502, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwan CY, Putney JW., Jr Uptake and intracellular sequestration of divalent cations in resting and methacholine-stimulated mouse lacrimal acinar cells. Dissociation by Sr2+ and Ba2+ of agonist-stimulated divalent cation entry from the refilling of the agonist sensitive intracellular pool. J Biol Chem 265: 678–684, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Xie Z. The Na/K-ATPase/Src complex and cardiotonic steroid-activated protein kinase cascades. Pflügers Arch 457: 635–644, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang M, Cai T, Tian J, Qu W, Xie ZJ. Functional characterization of Src interacting Na/K-ATPase using RNA interference assay. J Biol Chem 281: 19709–19719, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linde CI, Karashima E, Raina H, Zulian A, Wier WG, Hamlyn JM, Ferrari P, Blaustein MP, Golovina VA. Increased arterial smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling, vasoconstriction, and myogenic reactivity in Milan hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H611–H620, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Xie ZJ. The sodium pump and cardiotonic steroids-induced signal transduction protein kinases and calcium-signaling microdomain in regulation of transporter trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 1237–1245, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Ivanov AV, Gable ME, Jolivel F, Morrill GA, Askari A. Comparative properties of caveolar and noncaveolar preparations of kidney Na+/K+-ATPase. Biochemistry 50: 8664–8673, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenz JN, Loreaux EL, Dostanic-Larson I, Lasko V, Schnetzer JR, Paul RJ, Lingrel JB. ACTH-induced hypertension is dependent on the ouabain-binding site of the alpha2-Na+-K+-ATPase subunit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H273–H280, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manunta P, Ferrandi M, Bianchi G, Hamlyn JM. Endogenous ouabain in cardiovascular function and disease. J Hypertens 27: 9–18, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manunta P, Hamilton J, Rogowski AC, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Chronic hypertension induced by ouabain but not digoxin in the rat: antihypertensive effect of digoxin and digitoxin. Hypertens Res 23, Suppl: S77–S85, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manunta P, Rogowski AC, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Ouabain-induced hypertension in the rat: relationships among plasma and tissue ouabain and blood pressure. J Hypertens 12: 549–560, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mason DT. Effects of cardiac glycoside on vascular system. In: Cardiac Glycosides. Part 1: Experimental Pharmacology, edited by Greef F. New York: Springer, 1981. p. 497–515 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noel F, Fagoo M, Godfraind T. A comparison of the affinities of rat (Na+ + K+)-ATPase isozymes for cardioactive steroids, role of lactone ring, sugar moiety and KCl concentration. Biochem Pharmacol 40: 2611–2616, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Brien WJ, Lingrel JB, Wallick ET. Ouabain binding kinetics of the rat alpha two and alpha three isoforms of the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphate. Arch Biochem Biophys 310: 32–39, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oda Y, Renaux B, Bjorge J, Saifeddine M, Fujita DJ, Hollenberg MD. cSrc is a major cytosolic tyrosine kinase in vascular tissue. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 77: 606–617, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierre SV, Sottejeau Y, Gourbeau JM, Sanchez G, Shidyak A, Blanco G. Isoform specificity of Na-K-ATPase-mediated ouabain signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F859–F866, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pulina MV, Zulian A, Berra-Romani R, Beskina O, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Baryshnikov SG, Papparella I, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Golovina VA. Upregulation of Na+ and Ca2+ transporters in arterial smooth muscle from ouabain hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H263–H274, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raina H, Zhang Q, Rhee AY, Pallone TL, Wier WG. Sympathetic nerves and endothelium influence the vasoconstrictor effect of low concentrations of ouabain in pressurized small arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H2093–H2101, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi G, Manunta P, Hamlyn JM, Pavan E, De Toni R, Semplicini A, Pessina AC. Immunoreactive endogenous ouabain in primary aldosteronism and essential hypertension: relationship with plasma renin, aldosterone and blood pressure levels. J Hypertens 13: 1181–1191, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides: their roles in hypertension, salt metabolism, and cell growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C509–C536, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulte KL, van Gemmeren D, Thiede HM, Meyer-Sabellek W, Gotzen R, Distler A. Ouabain-induced elevation in forearm vascular resistance, calcium entry and alpha-adrenoceptor blockade, and release and removal of noradrenaline. J Hypertens Suppl 5: S215–S218, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shelly DA, He S, Moseley A, Weber C, Stegemeyer M, Lynch RM, Lingrel J, Paul RJ. Na+ pump alpha 2-isoform specifically couples to contractility in vascular smooth muscle: evidence from gene-targeted neonatal mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C813–C820, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tian J, Cai T, Yuan Z, Wang H, Liu L, Haas M, Maksimova E, Huang XY, Xie ZJ. Binding of Src to Na+/K+-ATPase forms a functional signaling complex. Mol Biol Cell 17: 317–326, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Touyz RM, Wu XH, He G, Park JB, Chen X, Vacher J, Rajapurohitam V, Schiffrin EL. Role of c-Src in the regulation of vascular contraction and Ca2+ signaling by angiotensin II in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Hypertens 19: 441–449, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vazquez G, Wedel BJ, Kawasaki BT, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Obligatory role of Src kinase in the signaling mechanism for TRPC3 cation channels. J Biol Chem 279: 40521–40528, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang JG, Staessen JA, Messaggio E, Nawrot T, Fagard R, Hamlyn JM, Bianchi G, Manunta P. Salt, endogenous ouabain and blood pressure interactions in the general population. J Hypertens 21: 1475–1481, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Z, Zheng M, Li Z, Li R, Jia L, Xiong X, Southall N, Wang S, Xia M, Austin CP, Zheng W, Xie Z, Sun Y. Cardiac glycosides inhibit p53 synthesis by a mechanism relieved by Src or MAPK inhibition. Cancer Res 69: 6556–6564, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res 90: 248–250, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Withering W. An Account of the Foxglove and Some of Its Medical Uses: With Practical Remarks on Dropsy and Other Diseases. London: Robinson, p. 207, 1785 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu L, Kappler CS, Menick DR. The role of p38 in the regulation of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger expression in adult cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 735–743, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoda A. Association and dissociation rate constants of the complexes between various cardiac monoglycosides and Na, K-ATPase. Ann NY Acad Sci 242: 598–616, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan CM, Manunta P, Hamlyn JM, Chen S, Bohen E, Yeun J, Haddy FJ, Pamnani MB. Long-term ouabain administration produces hypertension in rats. Hypertension 22: 178–187, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang J, Lee MY, Cavalli M, Chen L, Berra-Romani R, Balke CW, Bianchi G, Ferrari P, Hamlyn JM, Iwamoto T, Lingrel JB, Matteson DR, Wier WG, Blaustein MP. Sodium pump alpha2 subunits control myogenic tone and blood pressure in mice. J Physiol 569: 243–256, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang J, Ren C, Chen L, Navedo MF, Antos LK, Kinsey SP, Iwamoto T, Philipson KD, Kotlikoff MI, Santana LF, Wier WG, Matteson DR, Blaustein MP. Knockout of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in smooth muscle attenuates vasoconstriction and l-type Ca2+ channel current and lowers blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1472–H1483, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zulian A, Baryshnikov SG, Linde CI, Hamlyn JM, Ferrari P, Golovina VA. Upregulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and TRPC6 contributes to abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis in arterial smooth muscle cells from Milan hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H624–H633, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]