Abstract

A striking feature of mammalian genomes is the paucity of the CG dinucleotide. There are approximately 20,000 regions termed CpG islands where CGs cluster. This represents 5% of all CGs and 1% of the genome. CpG islands are typically unmethylated and are often promoters for housekeeping genes. The remaining 95% of CG dinucleotides are disposed throughout 99% of the genome and are typically methylated and found in half of all promoters. CG methylation facilitates binding of the C/EBP family of transcription factors, proteins critical for differentiation of many tissues. This allows these proteins to localize in the methylated CG poor regions of the genome where they may produce advantageous changes in gene expression at nearby or more distant regions of the genome. In this review, our growing understanding of the consequences of CG methylation will be surveyed.

Keywords: C/EBP, CG, CG dinucleotide, CGI, CpG, CpG island, cytosine, methylation, TFBS, tissue specific

CG methylation: old history

Methylcytosine (Figure 1A) was first identified in DNA over 60 years ago by Wyatt, who said:

“The amounts in which it occurs, however, varying with the source but constant from a given source, suggest that it is an essential constituent of certain DNAs, and no accident of enzyme action.”

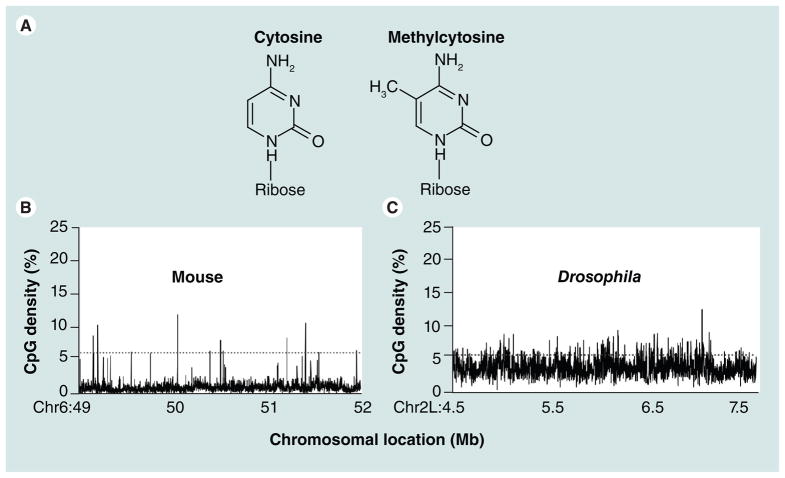

Figure 1. Chemical structure of cytosine and enrichment of CG dinucleotide.

(A) Chemical structure of cytosine and methylcytosine. (B) Frequency of CG dinucleotide at a megabase scale across the mouse and Drosophila genomes shows the presence of CpG clusters, called CG islands, only in the mouse genome. Percentage of CpG dinucleotide is calculated for a 1000-bp window.

He went further:

“ it would be interesting to know whether the observation that methylcytosine is present in higher organisms but lacking in microorganisms holds generally, and if so, at what point in the evolutionary scale it first appears.” [1]

Bird and Southern took a major step forward when they used restriction enzymes that are methylation sensitive to evaluate ribosomal genes in Xenopus laevis [2]. This was at a time before molecular cloning when ribosomal genes, which have multiple copies in the genome, were studied because they could be purified biochemically. They showed that amplified rDNA is cleaved at many sites by each enzyme while somatic rDNA is relatively resistant to digestion. Furthermore, for most detected CGs, the level of methylation was high (~99%). However, one site was unmethylated in 30–60% of rDNA repeat units. These results demonstrated that methylcytosine occurs at specific places in the genome and is not a random modification.

Bird examined many species and concluded:

“All the insects [3,4] studied … in showing no evidence of methylation, while all the non-arthropod invertebrates … conformed to the partially methylated Echinus pattern. Similarly, 13 vertebrates … all displayed high levels of DNA methylation similar to the mouse and Xenopus laevis” [5].

Species that have a heavily methylated genome, such as vertebrates, tend to have low CG density (Figure 1B) and an elevation of the deamination product TG [6]. By contrast, genomes without CG methylation have the expected CG density (Figure 1B) lending support to the notion that methyl CG deaminates to TG. Bird concluded by wondering why CG methylation may occur:

“Might the function of DNA methylation be to increase the mutation rate? It is difficult to argue conclusively for or against this possibility … The necessary change in mutation rate by cytosine methylation as a mechanism is shortsighted because all the cytosines in CG dinucleotides will disappear, thus it has short-term gain but in long-term it will stop functioning” [6].

The mammal genomes are living with this Faustian bargain.

The next step forward was the realization that mammalian genomes have islands of sequence that are not depleted for CG dinucleotides, termed CG islands (CGIs), and that these CGIs are typically unmethylated while the rest of the genome is generally methylated [7–9]. Along with this insight, it became clear that methylation of CGIs suppressed gene expression. Bird conceptualized the properties of CGI as follows:

“The model supposes that the availability of island sequences is achieved by bound factors (proteins) and that these same factors sterically exclude the methylase. The factors are presumed to have an affinity for sequences containing CpG, and to lose this affinity if CpGs are methylated” [9].

Subsequent work has confirmed that methylation suppresses binding of factors that localize in proximal promoters [10–12].

On the question of the function of CG methylation in CG poor regions of the genome, Bird said:

“Given that there are usually rather few CpGs near tissue-specific genes, and since what CpGs there are are methylated in the germline and therefore hypermutable, one would not expect to find CpG or methylation built into the activation mechanism of genes of this type” [9].

This seems like a reasonable assertion and the ponderous observation is that the exact opposite is true. The unstable and methylated CG sequences are the favored binding sites for the C/EBP family of transcription factors involved in cell differentiation in many cell types [13]. The consequences of having sequence-specific trans-activating proteins bind the genetically unstable part of the genome are not obvious.

In the early 1980s, there was considerable interest in the suggestion that CG demethylation is a trigger to initiate activation of tissue-specific gene expression. Using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes, investigators correlated gene expression with changes in CG methylation. Many studies identified CG demethylation accompanying tissue-specific gene activation, but it tended to occur after gene expression had started, indicating that the change in CG methylation is a consequence of gene expression, not a cause [14,15]. Kunnath et al. studied methylation and gene expression of rat albumin and AFP genes and concluded that:

“These findings suggest that specific methylation changes are associated with changes in gene expression, but that this association is not adequately described by the simple hypothesis that methylation turns genes off ” [16].

These studies did not suggest that CG methylation facilitated transcription factor (TF) binding to tissue-specific promoters thus driving gene expression as was suggested recently [13].

In the late 1980s, Bird’s laboratory identified [17] and subsequently cloned [18] a protein named MBP that preferentially bound methylated CG and was subsequently shown to have repressive properties on gene expression [19]. These results indicate that CG methylation can have two functions to silence CGIs: the first is by inhibiting TF binding and the second is by facilitating binding of proteins with repressive properties [11]. Focus turned to the repressive properties of CG methylation, particularly in cancer where CG methylation of CGIs silences tumor suppressor genes [19,20]. A cautionary note is that during the last 20 years many investigators have used transient transfection assays to evaluate both the cis elements (DNA) and trans factors (protein) critical for gene expression without replicating the methylation status of the endogenous DNA.

The next major technological advance was the advent of sodium bisulfite sequencing, which converts cytosine residues to uracil, but leaves 5-methylcytosine residues unaffected [21]. This technology allows the investigation of the methylation status of any CG dinucleotide in the genome. This allowed study of specific promoters to determine if changes in methylation accompanied changes in gene expression.

In 1994, Bird and coworkers examined the mouse aprt promoter in an attempt to find the mechanism by which CG islands remain free of methylation [22]. They undertook a detailed examination of the promoter region and concluded that peripherally located Sp1 sites are necessary to keep the aprt island methylation free. Although the results are clear, the mechanism of how SP1 sites keep nearby CGs unmethylated is not understood and difficult to investigate.

CG methylation: new history

A new era began with the generation of genomic scale data that determined the methylation status of the entire genome. Initially, investigators were using an antibody that recognized methylcytosine to determine the methylation status of any region of the genome [23–25]. With the advent of sequencing methods that could produce long reads (100 bps), it became possible to map sodium bisulfite treated DNA to the genome [26–28], something that is impossible with shorter (35 bp) reads [29].

Genomic studies show that expressed promoters tend to be unmethylated while methylated promoters tend to be inactive [30–32]. However, methylated promoters can be active [13,31,33–36]. An important point to keep in mind when examining genomic data is that what distinguishes cells from each other are tissue-specific promoters. Although they are not abundant, they are what make cells different from each other. In examining gene-expression profiles, the abundant and unmethylated housekeeping promoters are predominant and the few expressed methylated tissue-specific promoters seem insignificant. In another cell, the same unmethylated house-keeping promoters are expressed but a different small set of methylated tissue-specific promoters is expressed. This has resulted in the common misconception that methylation is inherently bad for gene expression. The few expressed genes with methylated promoters are lost in the abundance of active unmethylated promoters [37].

Promoters have been grouped into three classes based on their CG density: low CG content promoters (LCP), high CG content promoters and intermediate CG content promoters [31]. However, when the methylation status of an entire promoter (−1000 bp to +500 bp) is determined using methyl CG immunoprecipitation, two distinct groups are observed (Figure 2) [13]. Promoters that are CG rich tend to be unmethylated while promoters that are CG poor tend to be methylated. The majority of the high CG content promoters, which tend to be CGI promoters, are unmethylated and are associated with the ubiquitously expressed housekeeping genes [30,31,38,39]. Promoters with an intermediate number of CGs have the most variability in methylation; some have high methylation values while others have low CG methylation (Figure 2). These promoters may change their methylation status in a regulated manner to modify activity. By contrast, LCPs are methylated in somatic cells and are associated with tissue-specific genes [31]. Recently, the authors reported that methylation of these LCPs is required for the activation of some tissue-specific genes [13]. CG methylation increases binding to canonical transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) for C/EBP family members. C/EBP binds these methylated TFBS in the LCPs of tissue specific genes and mediates their activation. When primary newborn mouse keratinocytes were differentiated, many genes with methylated CG poor proximal promoters became activated [13] even though promoter methylation did not change with differentiation. Similar results were observed using newborn mouse dermal fibroblasts differentiated into adipocytes, a different set of genes with methylated CG poor promoters became activated upon differentiation.

Figure 2. CG methylation status of mouse promoters.

Immunoprecipitated methylated DNA is hybridized to NimbleGen promoter arrays and the average methylation for each promoter is determined. Average methylation level (in log2) is plotted against number of CG dinucleotides (in log10) for each promoter. Two distinct clusters are formed, which are demarcated by the line. One cluster consists of CG-poor promoters, where methylation increases with the CG density and they are named as methylated promoters. The second cluster consists of CG-rich promoters, where average methylation is low and they are termed as unmethylated promoters.

MeDIP: Methyl CG immunoprecipitation. Reproduced from [13].

The importance of CG methylation for promoter function was examined by global demethylation using either 5-azacytidine or by depletion of DNMT1, the maintenance methylase. Demethylation inhibited C/EBPα binding preferentially to methylated promoters. Furthermore, these promoters could not be activated during differentiation in both primary keratinocyte and adipocyte differentiation systems suggesting a positive link between methylation, C/EBPα binding, and differentiation. Transient transfections confirmed that C/EBPα preferentially activated methylated tissue-specific promoters [13]. The authors, as well as others, have observed that these tissue-specific low CG promoters are methylated irrespective of their expression [13,31]. Genomic studies have shown that the demethylation by 5-azacytidine causes both gene activation and gene repression [13,34,35]. While gene activation by demethylation is mediated by the well-known role of repression by methylation, gene repression by demethylation could be a consequence of the newly identified role of activation by methylation.

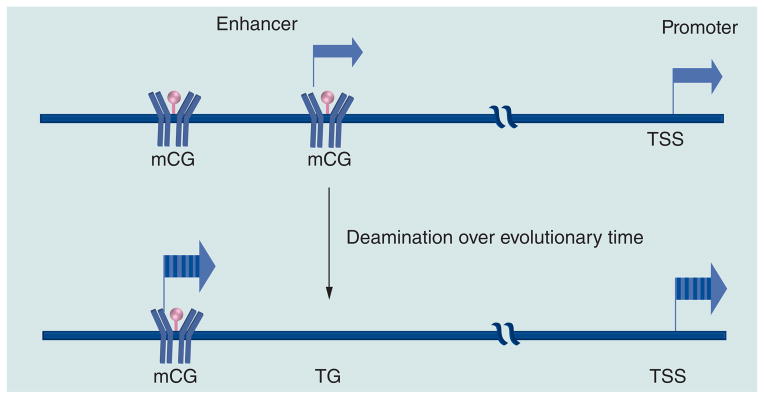

Mammalian genomes are divided into two parts, the CG rich regions that are unmethylated, genetically stable and activate essential cellular functions, and the CG poor regions that are methylated, genetically unstable and activate tissue-specific gene expression. Thus, knowing only the TFBS and the effect of methylation on DNA binding can give clues about the function of a TF. TFBS containing two CG dinucleotides (e.g., E2F [TTTCGCGC] and BoxA [TCTCGCGA]) are rare in the genome and occur primarily in unmethylated CGIs. Methylation inhibits E2F binding [40], which restricts binding to the CGI [9]. For TFBS containing one CG dinucleotide, methylation can either inhibit or improve binding. For example, CREB binds its TFBS (TGACGTCA) better when unmethylated [10,12] and it localizes in the CGI and regulates essential cellular functions. C/EBPα, in contrast, binds its TFBS (TTGCGCAA) better when methylated and facilitates localization in the CG poor regions of the genome [13]. The importance of CG methylation on the conservation of TFBS is vividly shown for the CRE motif (TGACGTCA), C/EBP motif (TTGCGCAA) and SP1 motif (CCCGCCC). The unmethylated occurrences are conserved while the methylated occurrences are less conserved with the CG dinucleotide being the least conserved reflecting the deamination of the methylated cytosine (Figure 3). Methylated occurrences of C/EBP binding sites are bound and functional although they are evolutionarily unstable. No deamination is observed during development.

Figure 3. PhyloP scores for CREB (TGACGTCA), SP1 (CCCGCCC) and C/EBP (TTGCGCAA) canonical motifs divided into unmethylated and methylated occurrences in newborn dermal fibroblast primary cultures with a 50X methylome.

The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of occurrences in the mouse genome having PhyloP score and methylation coverage. Note that the methylated sequences are less stable than the unmethylated sequences.

A consequence of rapid mutation of functional motifs is that it speeds up evolution, allowing other sequences in the genome to acquire new functions more quickly because the old function has disappeared (Figure 4). This conjecture has precedence in many fields and how it occurs in biological systems is potentially observed in methyl-associated CG-SNPs, which are considered as surrogate markers for germline CG methylation [41]. The TFBS without CGs potentially regulate which CGs are methylated, producing different results in different cell types. Determining how this occurs mechanistically is a challenge going forward.

Figure 4. Methyl CG deamination produces new functions at methylated transcription factor binding sites elsewhere in the genome.

mC: Methylated cytosine; TSS: Transcription start site.

Development, differentiation & cancer: differentially methylated regions

During development, the genome undergoes complex changes in CG methylation resulting in differentiated cells having different CG methylation patterns [42]. Excitement in the field comes from the presumption that the differences in CG methylation between cells can help explain the distinctness of cell type. This conversation is just beginning.

Immediately after fertilization and prior to the first cell division, the paternal genome undergoes a genome-wide demethylation [43–46]. After the first cell cycle, the maternal genome also become demethylated, except for the imprinted genes, until the formation of the blastocyst [47,48]. However, in the primordial germ cells, parental imprinting is erased by DNA demethylation [49]. During blastocyst formation, DNA methylation levels of the pluripotent stem cells are restored by the de novo methyltransferases and the earliest cell fate decisions are established [50–52]. These tissue-specific differentially methylated regions are key signatures for the corresponding tissues.

These methylation patterns are critical for proper development as deletion of either maintenance (Dnmt1) or de novo methyltransferase (Dnmt3a/3b) causes loss of pluripotency and proper differentiation potential; however, they maintain their ability to self renew [13,53–55]. A recent genome-wide study, reported that cytosine methylation of non-CG dinucleotides is prevalent in the embryonic stem cells (ESCs) but not in fibroblasts, thus expanding the complexity of this epigenetic mark during development [27,42]. The recent identification of enzymes involved in demethylation of methyl CG [56–60] opens a window to understanding the mechanisms that drive localization of these enzymes.

In 1979, Lapeyre and Becker showed that hepatocarcinomas were undermethylated by 20–45% [61], a trend observed by others [20,62–64]. In cancers, global hypomethylation occurs at gene bodies, transposable elements, repetitive sequences and the CG poor regions of the genome, whereas hypermethylation occurs at unmethylated CGI promoters inhibiting expression of tumor suppressor genes. These cancer specific differentially methylated regions are typically at the CGIs and always associated with the inhibition of gene expression and are a major focus of research [20,64]. The consequences of global hypomethylation are typically focused on the activation of repressed transposable elements, generating the chromosomal instability and loss of imprinting [65–67]. Hypomethylation of transposable elements causes them to transcribe or translocate to other genomic regions to inactivate tumor suppressor genes and facilitate genomic rearrangements. Hypomethylation can also lead to loss of imprinting, which is reported to be associated with the disease development including cancer [66–69]. Global DNA hypomethylation may contribute to the development of cancer by inhibiting differentiation through the inactivation of tissue-specific methylated CG poor promoters that need to be methylated for C/EBP binding and activation [13]. The decrease in methylation in the CG poor regions of the genome in cancer cells could inhibit differentiation and facilitate the cancer phenotype. One consequence of having differentiation be dependent on methylation is that stem cells that are unmethylated cannot differentiate, thus protecting stem cells from death.

Hydroxymethylation

The mammalian genome contains 5-hydroxy-methylcytosine (5hmC), which is the oxidation product of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) catalyzed by the TET family of enzymes [57,70–75]. The TET1 and TET2 enzymes are highly expressed in ESCs and regulate the expression of pluripotency-related genes together with the potential of ESCs to differentiate into the embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. Loss of catalytic activity of TET2 is strongly reported to be associated with the myeloid malignancies [72]. Bone marrow samples from patients with TET2 mutant showed low levels of hydromethylcytosine compared with the normal healthy controls. Traditional bisulphite conversion and high-throughput sequencing does not distinguish between 5mC and 5hmC. Affinity purification-based methods cannot precisely locate 5hmC nor accurately determine its relative abundance at each modified site [76]. Recently a genome-wide approach has been proposed, Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing for mapping 5hmC at base resolution and quantifying the relative abundance of 5hmC as well as 5mC when combined with the traditional bisulfite sequencing [77]. 5hmC is more abundant in the enhancers, DNase1 hypersensitive sites, P300 and CTCF binding sites. It has shown to have sequence bias and strand asymmetry. Previously, it has been observed that 5hmC are enriched in CG rich regions near the transcription start sites; however, recent observations suggest that they are enriched in the low CG rich promoters [77]. Understanding the function of 5hmC may help unravel the stable change in gene expression that occurs at tissue-specific genes.

Conclusion & future perspective

The recent drop in the price of DNA sequencing has made determining the methylation status of all 20 million CGs in mammalian genomes possible. The methylome is not as variable as many expected, CG methylation did not change with TGF-β induction of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [78]. The hope is that knowing the methylome of a cell, the information can be decoded to gain insight into the physiological and pathological state of a cell, allowing diagnosis of an ailment even before it manifests itself clinically. However, the decoding of the methylome is daunting. We are taking the perspective that CG methylation affects TF binding and this fact can be used to help understand the methylome. New technologies allow the high-throughput evaluation of how CG methylation affects DNA binding specificity of TFs [79,80]. It will be important to determine the TF that binds methylated TFBS and that is involved in the cell differentiation. It will be interesting to determine how CG methylation is mediating the yin-yang between growth and differentiation via TF binding unmethylated or methylated TFBS, respectively. 5hmC, the recently discovered oxidation product of methylcytosine is enriched in both ESCs and Purkinje neurons. These modifications are enriched in the low CG promoters, which are mainly involved in tissue-specific gene expression. This modification may hold the key to stable changes in gene expression that occur in both pluripotent and differentiated cell types.

Executive summary.

CG methylation: old history

CG dinucleotides are rare in mammals.

Species that have a heavily methylated genome, such as vertebrates, tend to have low CG density, while genomes without CG methylation have the expected CG density.

Approximately 70% of CG dinucleotides in mammalian genomes are methylated on the 5-carbon of cytosine.

CG dinucleotides occur in clusters called CG islands (approximately 20,000 in mouse genome).

CGIs are typically unmethylated and are associated with the promoters for housekeeping genes.

Hypermethylation of CGI promoters occurs in cancer and is associated with gene silencing.

CG methylation: new history

CG poor promoters are generally methylated and associated with tissue-specific genes.

CG methylation enhances binding of C/EBP transcription factors.

CG methylation is essential for the activation of some tissue specific genes.

Methylated cytosines are more prone to being mutated by the process of deamination, and thus are 40-times evolutionarily less stable.

A consequence of having transcription factors bind to methylated and unstable sequences to drive tissue-specific gene expression is that the regulation of these genes has accelerated evolution.

Development, differentiation & cancer: differentially methylated regions

In cancers, global hypomethylation occurs at gene bodies, transposable elements, repetitive sequences and the CG poor regions of the genome, and may inhibit differentiation.

Genomic hypermethylation in cancer has been observed most often in CGIs and is associated with inhibition of gene expression.

Hydroxymethylation

5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) is the oxidation product of 5-methylcytosine by the TET family of enzymes.

5hmC is more abundant in the distant regulatory regions (e.g., in the enhancers, DNase1 hypersensitive sites, P300 and CTCF binding sites.

Occurrence of 5hmC has shown to have sequence bias and strand asymmetry.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their laboratory members for their encouragement and support.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact: reprints@futuremedicine.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work is supported by the intramural project of National Cancer Institute, NIH, USA. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1▪.Wyatt GR. Recognition and estimation of 5-methylcytosine in nucleic acids. Biochem J. 1951;48(5):581–584. doi: 10.1042/bj0480581. Shows that methylcytosine exists and had different abundance in different samples, suggesting some biological significance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird AP, Southern EM. Use of restriction enzymes to study eukaryotic DNA methylation: I. The methylation pattern in ribosomal DNA from Xenopus laevis. J Mol Biol. 1978;118(1):27–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams RL, McKay EL, Craig LM, Burdon RH. Methylation of mosquito DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;563(1):72–81. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rae PM, Steele RE. Absence of cytosine methylation at C-C-G-G and G-C-G-C sites in the rDNA coding regions and intervening sequences of Drosophila and the rDNA of other insects. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6(9):2987–2995. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.9.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird AP, Taggart MH. Variable patterns of total DNA and rDNA methylation in animals. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8(7):1485–1497. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.7.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird AP. DNA methylation and the frequency of CpG in animal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8(7):1499–1504. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DN, Taggart MH, Bird AP. Unmethylated domains in vertebrate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11(3):647–658. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bird A, Taggart M, Frommer M, Miller OJ, Macleod D. A fraction of the mouse genome that is derived from islands of nonmethylated, CpG-rich DNA. Cell. 1985;40(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bird AP. CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature. 1986;321(6067):209–213. doi: 10.1038/321209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iguchi-Ariga SM, Schaffner W. CpG methylation of the cAMP-responsive enhancer/promoter sequence TGACGTCA abolishes specific factor binding as well as transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1989;3(5):612–619. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tate PH, Bird AP. Effects of DNA methylation on DNA-binding proteins and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3(2):226–231. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozenberg JM, Shlyakhtenko A, Glass K, et al. All and only CpG containing sequences are enriched in promoters abundantly bound by RNA polymerase II in multiple tissues. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13▪▪.Rishi V, Bhattacharya P, Chatterjee R, et al. CpG methylation of half-CRE sequences creates C/EBPα binding sites that activate some tissue-specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(47):20311–20316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008688107. Shows that C/EBPα preferentially binds methylated sequences and localizes in methylated promoters of tissue-specific genes and is critical for their activation with differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilks AF, Cozens PJ, Mattaj IW, Jost JP. Estrogen induces a demethylation at the 5′ end region of the chicken vitellogenin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79(14):4252–4255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.14.4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grainger RM, Hazard-Leonards RM, Samaha F, Hougan LM, Lesk MR, Thomsen GH. Is hypomethylation linked to activation of δ-crystallin genes during lens development? Nature. 1983;306(5938):88–91. doi: 10.1038/306088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunnath L, Locker J. Developmental changes in the methylation of the rat albumin and α-fetoprotein genes. EMBO J. 1983;2(3):317–324. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meehan RR, Lewis JD, McKay S, Kleiner EL, Bird AP. Identification of a mammalian protein that binds specifically to DNA containing methylated CpGs. Cell. 1989;58(3):499–507. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis JD, Meehan RR, Henzel WJ, et al. Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA. Cell. 1992;69(6):905–914. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90610-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, et al. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998;19(2):187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20▪▪.Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome – biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(10):726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. Up-to-date detailed review on cancer epigenetics with a focus on epigenetic markers for cancer detection, diagnosis and prognosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, et al. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(5):1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacLeod D, Charlton J, Mullins J, Bird AP. Sp1 sites in the mouse aprt gene promoter are required to prevent methylation of the CpG island. Genes Dev. 1994;8(19):2282–2292. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Down TA, Rakyan VK, Turner DJ, et al. A Bayesian deconvolution strategy for immunoprecipitation-based DNA methylome analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(7):779–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y, et al. Targeted and genome-scale strategies reveal gene-body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(4):361–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25▪.Taiwo O, Wilson GA, Morris T, et al. Methylome analysis using MeDIP-seq with low DNA concentrations. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(4):617–636. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.012. Developed a method to study methylomes with low concentrations of DNA using methylated DNA immunoprecipitation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lister R, O’Malley RC, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2008;133(3):523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27▪▪.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462(7271):315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. First whole-genome DNA methylome of two human cells using bisulfite treatment followed by next-generation sequencing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471(7336):68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454(7205):766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eckhardt F, Lewin J, Cortese R, et al. DNA methylation profiling of human chromosomes 6, 20 and 22. Nat Genet. 2006;38(12):1378–1385. doi: 10.1038/ng1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39(4):457–466. doi: 10.1038/ng1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen KD, Timp W, Bravo HC, et al. Increased methylation variation in epigenetic domains across cancer types. Nat Genet. 2011;43(8):768–775. doi: 10.1038/ng.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elder JT, Zhao X. Evidence for local control of gene expression in the epidermal differentiation complex. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11(5):406–412. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2002.110503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serman L, Dodig D. Impact of DNA methylation on trophoblast function. Clin Epigenetics. 2011;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Botchkarev VA, Gdula MR, Mardaryev AN, Sharov AA, Fessing MY. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(11):2505–2521. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, et al. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science. 2012;336(6080):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1219328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011;25(10):1010–1022. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(5):1412–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40▪▪.Campanero MR, Armstrong MI, Flemington EK. CpG methylation as a mechanism for the regulation of E2F activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6481–6486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100340697. Showed that methylation differentially regulates the response of distinct E2F elements to different E2F factors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sigurdsson MI, Smith AV, Bjornsson HT, Jonsson JJ. HapMap methylation-associated SNPs, markers of germline DNA methylation, positively correlate with regional levels of human meiotic recombination. Genome Res. 2009;19(4):581–589. doi: 10.1101/gr.086181.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laurent L, Wong E, Li G, et al. Dynamic changes in the human methylome during differentiation. Genome Res. 2010;20(3):320–331. doi: 10.1101/gr.101907.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reik W, Dean W, Walter J. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science. 2001;293(5532):1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1063443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rougier N, Bourc’his D, Gomes DM, et al. Chromosome methylation patterns during mammalian preimplantation development. Genes Dev. 1998;12(14):2108–2113. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer W, Niveleau A, Walter J, Fundele R, Haaf T. Demethylation of the zygotic paternal genome. Nature. 2000;403(6769):501–502. doi: 10.1038/35000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oswald J, Engemann S, Lane N, et al. Active demethylation of the paternal genome in the mouse zygote. Curr Biol. 2000;10(8):475–478. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlson LL, Page AW, Bestor TH. Properties and localization of DNA methyltransferase in preimplantation mouse embryos: implications for genomic imprinting. Genes Dev. 1992;6(12B):2536–2541. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H. DNA methyltransferase is actively retained in the cytoplasm during early development. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(1):25–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hajkova P, Ancelin K, Waldmann T, et al. Chromatin dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the mouse germ line. Nature. 2008;452(7189):877–881. doi: 10.1038/nature06714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farthing CR, Ficz G, Ng RK, et al. Global mapping of DNA methylation in mouse promoters reveals epigenetic reprogramming of pluripotency genes. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(6):e1000116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Straussman R, Nejman D, Roberts D, et al. Developmental programming of CpG island methylation profiles in the human genome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(5):564–571. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Epsztejn-Litman S, Feldman N, Abu-Remaileh M, et al. De novo DNA methylation promoted by G9a prevents reprogramming of embryonically silenced genes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(11):1176–1183. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takizawa T, Nakashima K, Namihira M, et al. DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain. Dev Cell. 2001;1(6):749–758. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsumura A, Hayakawa T, Kumaki Y, et al. Maintenance of self-renewal ability of mouse embryonic stem cells in the absence of DNA methyltransferases Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. Genes Cells. 2006;11(7):805–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sen GL, Reuter JA, Webster DE, Zhu L, Khavari PA. DNMT1 maintains progenitor function in self-renewing somatic tissue. Nature. 2010;463(7280):563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature08683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu JK. Active DNA demethylation mediated by DNA glycosylases. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ito S, D’Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu H, D’Alessio AC, Ito S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine distribution reveals its dual function in transcriptional regulation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2011;25(7):679–684. doi: 10.1101/gad.2036011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cortellino S, Xu J, Sannai M, et al. Thymine DNA glycosylase is essential for active DNA demethylation by linked deamination-base excision repair. Cell. 2011;146(1):67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lapeyre JN, Becker FF. 5-methylcytosine content of nuclear DNA during chemical hepatocarcinogenesis and in carcinomas which result. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;87(3):698–705. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)92015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature. 1983;301(5895):89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(1):21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez-Paredes M, Esteller M. Cancer epigenetics reaches mainstream oncology. Nat Med. 2011;17(3):330–339. doi: 10.1038/nm.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roman-Gomez J, Jimenez-Velasco A, Agirre X, et al. Promoter hypomethylation of the LINE-1 retrotransposable elements activates sense/antisense transcription and marks the progression of chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2005;24(48):7213–7223. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cui H, Cruz-Correa M, Giardiello FM, et al. Loss of IGF2 imprinting: a potential marker of colorectal cancer risk. Science. 2003;299(5613):1753–1755. doi: 10.1126/science.1080902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feinberg AP. Imprinting of a genomic domain of 11p15 and loss of imprinting in cancer: an introduction. Cancer Res. 1999;59(Suppl 7):S1743–S1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogawa O, Eccles MR, Szeto J, et al. Relaxation of insulin-like growth factor II gene imprinting implicated in Wilms’ tumour. Nature. 1993;362(6422):749–751. doi: 10.1038/362749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaneda A, Feinberg AP. Loss of imprinting of IGF2: a common epigenetic modifier of intestinal tumor risk. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11236–11240. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70▪.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324(5929):929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. Observed the presence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in Purkinje neurons and the brain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71▪.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. Observed that Tet protein can catalyze conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in cultured cells and in vitro 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ko M, Huang Y, Jankowska AM, et al. Impaired hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine in myeloid cancers with mutant TET2. Nature. 2010;468(7325):839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature09586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dawlaty MM, Ganz K, Powell BE, et al. Tet1 is dispensable for maintaining pluripotency and its loss is compatible with embryonic and postnatal development. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(2):166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu TP, Guo F, Yang H, et al. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature. 2011;477(7366):606–610. doi: 10.1038/nature10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koh KP, Yabuuchi A, Rao S, et al. Tet1 and Tet2 regulate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine production and cell lineage specification in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(2):200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Szulwach KE, Li X, Li Y, et al. Integrating 5-hydroxymethylcytosine into the epigenomic landscape of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(6):e1002154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu M, Hon GC, Szulwach KE, et al. Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell. 2012;149(6):1368–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McDonald OG, Wu H, Timp W, Doi A, Feinberg AP. Genome-scale epigenetic reprogramming during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(8):867–874. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bulyk ML, Gentalen E, Lockhart DJ, Church GM. Quantifying DNA–protein interactions by double-stranded DNA arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(6):573–577. doi: 10.1038/9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Warren CL, Zhao J, Glass K, Rishi V, Ansari AZ, Vinson C. Fabrication of duplex DNA microarrays incorporating methyl-5-cytosine. Lab Chip. 2012;12(2):376–380. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20698b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]